Abstract

Fluorogenic organophosphate inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) homologous in structure to nerve agents provide useful probes for high throughput screening of mammalian paraoxonase (PON1) libraries generated by directed evolution of an engineered PON1 variant with wild-type like specificity (rePON1). Wt PON1 and rePON1 hydrolyze preferentially the less-toxic RP enantiomers of nerve agents and of their fluorogenic surrogates containing the fluorescent leaving group, 3-cyano-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (CHMC). To increase the sensitivity and reliability of the screening protocol so as to directly select rePON1 clones displaying stereo-preference towards the toxic SP enantiomer, and to determine accurately Km and kcat values for the individual isomers, two approaches were used to obtain the corresponding SP and RP isomers: (a) stereo-specific synthesis of the O-ethyl, O-n-propyl, and O-i-propyl analogs; (b) enzymic resolution of a racemic mixture of O-cyclohexyl methylphosphonylated CHMC. The configurational assignments of the SP and RP isomers, as well as their optical purity, were established by X-ray diffraction, reaction with sodium fluoride, hydrolysis by selected rePON1 variants, and inhibition of AChE. The SP configuration of the tested surrogates was established for the enantiomer with the more potent anti-AChE activity, with SP/RP inhibition ratios of 10–100, whereas the RP isomers of the O-ethyl and O-n-propyl were hydrolyzed by wt rePON1 about 600- and 70-fold faster, respectively, than the SP counterpart. Wt rePON1-induced RP/SP hydrolysis ratios for the O-cyclohexyl and O-i-propyl analogs are estimated to be ≫1000. The various SP enantiomers of O-alkyl-methylphosphonyl esters of CHMC provide suitable ligands for screening rePON1 libraries, and can expedite identification of variants with enhanced catalytic proficiency towards the toxic nerve agents.

Keywords: paraoxonase, catalytic bioscavenger, directed evolution, acetylcholinesterase, fluorogenic organophosphate, nerve agent, coumarin

1. Introduction

Organophosphate ester hydrolases (OPH) displaying multiple turnover, such as bacterial phosphotriesterases (PTE) and mammalian serum paraoxonases (PON1), have been demonstrated to have the capacity to serve as potential prophylactic drugs to counteract in vivo intoxication by nerve agents and organophosphate-based pesticides [1–5]. A significant obstacle in applying OPHs as antidotes against nerve agent intoxication is their preference for hydrolysis of the less toxic isomers of nerve agents with the RP absolute configuration at the phosphorous center [6–9]. All nerve agents are racemic mixtures due to the chiral phosphorous atom, with the more potent anti-AChE agents, i.e., the toxic isomers, being assigned the absolute configuration S around the P atom (SP) [10]. It should be pointed out, however, that the assignment of the SP configuration to the toxic isomers of sarin (GB), soman (GD), cyclosarin (GF) and VX (all liquids) has been suggested on the basis of deductive stereo-chemistry, and only indirect structural evidence exists to support this contention [11].

The combined application of computational design and directed evolution of mammalian PON1 has the potential to evolve a variant with reversed stereo-preference and kinetic properties that will qualify it to serve as a realistic candidate for prophylactic of nerve agent intoxications. The need to screen huge libraries of mutants, and to rapidly identify and select variants evolved to hydrolyze the toxic isomers, as well as the call for accurate biochemical characterization of kcat and Km of both the SP and RP enantiomers, necessitate the synthesis of the individual fluorogenic optical isomers. The synthesis and biochemical properties of racemic O-alkyl methylphosphonates containing coumarin analogs as the fluorogenic leaving group have already been described [12–14]. In order to qualify as catalytic scavenger drug candidates, rePON1 variants should be capable of hydrolyzing the toxic OP isomers at kcat/Km = 5x107 M−1min−1 (unpublished calculations). To achieve the desired specificity and efficacy towards the toxic isomers when reacting with racemic nerve agents, it was, therefore, necessary to develop stereo-specific methods for the synthesis of appropriate SP and RP fluorescent surrogates for screening of libraries, for improved selection, and for accurate biochemical characterization of promising catalytic variants.

In this report we describe the synthesis, purity, structural determination and biochemical properties of optical isomers of nerve agents in which the leaving groups fluoride (G agents) and N,N-dialkylaminoethanthiolo (V agents) were replaced by the fluorescent moiety, 3-cyano-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (CHMC) (Fig. 1). The SP enantiomers were utilized to screen libraries by fluorescence–activated cell sorting and by direct monitoring of the release of the CHMC leaving group by crude lysates in 96-well plates.

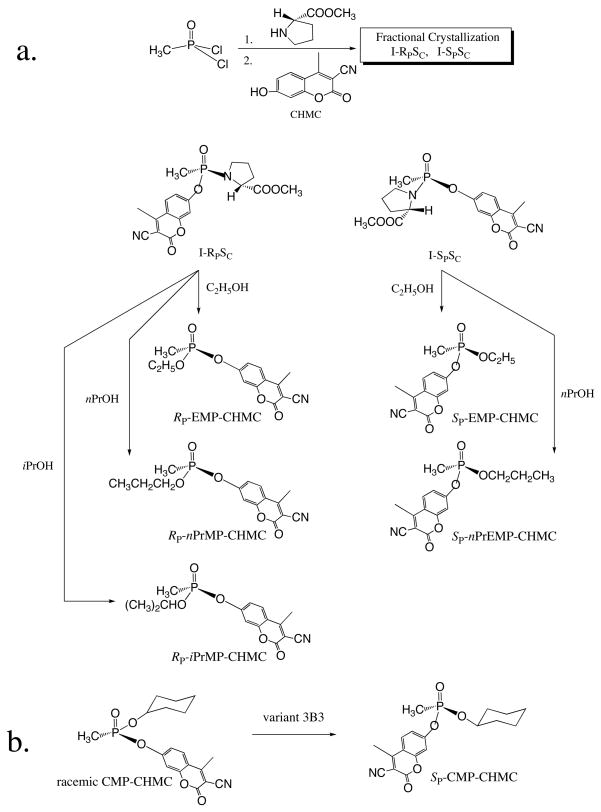

Fig.1.

Stereo-specific synthesis of RP- and SP-O-alkyl methylphosphonyl-CHMC esters from methylphosphonyl dichloride [CH3P(O)Cl2], L-proline methyl ester, and 3-cyano-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin (CHMC).The indicated absolute configuration was determined by X-ray diffraction of the corresponding crystals (Tables1&2) and by enzymatic hydrolysis (Fig. 3). Alcoholysis was catalyzed by 1 M H2SO4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals and enzymes

3-cyano-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarine (CHMC) and L-proline methyl ester hydrochloride were purchased from Aldrich (USA) and used as obtained. Methylphosphonyl dichloride (CH3POCl2) was prepared according to Moedritzer and Miller [15]. Recombinant human AChE (hAChE) was purchased from Sigma (USA) and Torpedo californica AChE (TcAChE) was purified as previously described [16]. Wt rePON1 is variant G3C9 of the gene shuffling products of 4 mammalian PON1s [17], and its H115W mutant were produced and characterized by Khersonsky and Tawfik [18]. Variants 3B3 and 3D8 were generated by directed evolution [19] using variant G3C9 as the lead rePON1 [Devi -Gupta et al., unpublished].

2.2 Synthesis of fluorescent racemic O-alkyl methylphosphonylated CHMCs

The syntheses of racemic O-alkyl methylphosphonylated CHMCs (for structures see Fig. 1a&b) were carried out essentially by a modified protocol based on the general procedure described by Amitai et al. [13]. The modified protocol replaced chromatography by crystallization after the removal of free CHMC and of the O-alkyl methylphosphonic acid by extraction of the chloroform solution containing the crude product, with 2% Na 2CO3, pH 9.0, at 4oC. The purity (>95%, containing <3% free CHMC) and homogeneity of the crystallized OP was established by tlc, 31P- and 1H-nmr spectroscopy, and absorption at 400 nm, following hydrolysis with (a) rePON1 variants capable of hydrolyzing either RP alone (3B3) or both RP and SP enantiomers (3D8), and by monitoring the release of total OP-bound CHMC in the presence of NaF at pH 8.0 (see below). Calculations were based on a value of 37,000 M−1cm−1 for the molar absorbance of CHMC at pH 8.0.

2.3 Reactions with NaF in dilute aqueous solution

(Note: the reader should be aware that this substitution reaction may contain non-hazardous low levels of G-type agent residues in dilute aqueous solution). The purity of the surrogate OPs was chemically determined as follows: 1 ml of 5–10 μM O-alkyl methylphosphonylated CHMC in 50 mM phosphate, pH 8.0, was reacted with 0.05–0.1 M NaF, and the release of CHMC was monitored until no further change was observed in the absorption at 400 nm.

2.4 Preparation of SP-O-cyclohexyl O-(3-cyano-4-methyl-7-coumarinyl) methylphopsphonate(SP-CMP-CHMC; Fig. 1b)

The SP isomer was prepared by partial enzymatic degradation of racemic CMP-CHMC, using a different protocol from that earlier described by Amitai et al. [13]. Hundred mg of racemic CMP-CHMC in 15 ml methanol were added drop-wise to 200 ml of 50 mM Tris-1 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0, and the clear solution was spiked with concentrated rePON1 variant 3B3 to produce a final concentration of 0.3 μM protein. Variant 3B3 is expected to hydrolyze only the RP isomer, and the progress of the reaction was monitored at room temperature (RT) by following the release of CHMC at 400 nm. After 30 min, when no further change in OD was observed, and the amount of CHMC approached half the theoretical value, 40 g NaCl were added, the aqueous solution was extracted with 3x75 ml CHCl3, and the combined organic layers were washed with 3x75 ml 2% Na2CO3, pH 9.0, pre-cooled to 4oC. The CHCl3 solution was dried over MgSO4, filtered and dried under vacuum.

The crude product was crystallized from ethyl acetate-hexane to give a 58% yield of SP-CMP-CHMC. 31P-nmr (124.1 MHz, CDCl3), δ 27.98 (9 lines). 1H-nmr (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.72 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 1H, 7.35 (dq J=7.5, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 4.60 (m, 1H), 2.80 (s, 3H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 1.85 (m, 2H), 1.70 (d, J=17 Hz, CH3-P), 1.6-1.3 (m, 7H).

2.5 Synthesis and resolution of diastereoisomers of (SP/RP)-N-(SC)-(proline methylester)- O-(3-cyano-4-methyl-oxo-2H-coumarin -7-yl ) methylphosphonate (I-SPSC and I-RPSC, see Fig.1a)

A solution of L-proline methyl ester hydrochloride ( 3.3. g, 20 mmol) and triethylamine (4.4 g, 40 mmol) in 60 ml CHCl3 was added drop-wise to a stirred pre-cooled (−10oC) solution of methylphosphonyl dichloride (2.66 g, 20 mmol) in 80 ml CHCl3. The progress of the reaction was monitored by 31P-nmr spectroscopy, and the reaction was completed within 45 min, as apparent from the full conversion of methylphosphonyl dichloride to the corresponding methyl ester of L-proline monochloridoamidate.

To the forgoing preparation, a slurry of CHMC (4.02 g, 20 mmol) and triethylamine (2.5 g, 25 mmol) in 80 ml CHCl3 was added, and the mixture was stirred at RT overnight. The resulting clear and homogenous solution was washed twice with 100 ml cold water (4oC), followed by washing twice with 50 ml cold 2% Na2CO3 solution. It was then dried over Na2SO4, and the CHCl3 removed under vacuum to give a yellow-green semi-solid residue which, upon trituratiion with ethyl acetate, turned into a crystalline suspension of a ~1:1 crude mixture of I-SPSC and I-RPSC. Yield, 6.0 g, 80%. 31P-nmr (124.1 MHz, CDCl3), showed as expected, two distinct signals indicating the presence of both the I-RPSC and I-SPSC diastereoisomers. Further, 1H-nmr (300 MHz, CDCl3) indicated 2 sets of signals for the CH3 of the methyl proline ester, and two CH3-assigned doublets of the CH3-P moiety. The CH3 at the 4 position of the coumarin ring was found to overlap for the two diastereoisomers to give a single peak.

The separation of the two diastereoisomers was achieved by repeated fractional crystallization using boiling benzene in which I-RPSC displayed greater solubility than I-SPSC. The soluble fractions of I-RPSC from the cumulative benzene mother liquors were recrystallized from ethyl acetate: hexane, m.p. 143-5oC, and the collected precipitates of I-SPSC recrystalized from benzene, m.p 181-3oC. The absolute configuration was determined by X-ray crystallography (Table 1). TLC (silica, 5% methanol/95% ethyl acetate) confirmed the homogeneity of the two diastereoisomers. The 31P-and 1H-nmr characteristics of the purified diastereoisomers are: I-RPSC: 31P (124.1 MHz, CDCl3), δ 35.7 ppm (1H: 31P coupled, 4 lines, q). 1H (300 MHz, CDCl3), δ 7.70 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd, J=7.5, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (bs, 1H), 4.40 (m,1H), 3.75 (s,3H), 3.40 (m, 1H), 3.20 (m, 1H), 2.75 (s,3H), 2.1-1.8 (m, 4H), 1.85 (d, J= 18Hz, 3H, CH3-P). [α]D20 =−76.5o (c=2, CHCl3). I-SPSC: 31P (124.1 MHz, CDCl3), δ 34.1 ppm (1H: 31P coupled, 4 lines, q). 1H (300 MHz, CDCl3), δ 7.70 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (bs, 1H), 4.30 (m,1H), 3.65 (s,3H), 3.35 (m, 1H), 2.75 (s, 3H), 2.1 (m, 2H), 1.9 (m, 2H), 1.70 (d, J= 18Hz, 3H, CH3-P).. [α]D20 =−47.5o (c=2, CHCl3).

Table 1.

Crystallographic data for I-SPSC, I-RPSC, SP-EMP-CHMC and RP –EMP-CHMC

| I-SPSC | I-RPSC | SP-EMP-CHMC | RP –EMP-CHMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C18H19N2O6P | C18H19N2O6P+0.5(C6H6) | C14H14NO5P | C14H14NO5P |

| Crystal description | Colorless plate | Colorless needle | Colorless plate | Colorless plate |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.15×0.08×0.03 | 0.40×0.15×0.15 | 0.50×0.40×0.10 | 0.57×0.13×0.04 |

| FW, gr mol−1 | 390.32 | 429.38 | 307.23 | 307.23 |

| Space group | P21 | P21212 | P21 | P21 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| a, Å | 10.8945(3) | 12.5780(4) | 7.3072(4) | 7.3015(3) |

| b, Å | 7.4485(2) | 24.3800(7) | 25.2207(13) | 25.2282(12) |

| c, Å | 11.3426(4) | 6.7055(2) | 7.7947(4) | 7.7996(4) |

| α, ° | ||||

| β, ° | 96.594(1) | 99.079(1) | 99.033(3) | |

| γ, ° | ||||

| Cell volume, Å3 | 914.34(5) | 2056.25(11) | 1417.38(13) | 1418.90(12) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Density(calc, gr cm−3) | 1.418 | 1.387 | 1.440 | 1.438 |

| μ, mm−1 | 0.189 | 0.175 | 0.215 | 0.215 |

| No. of reflections | 26282 | 15120 | 20660 | 12791 |

| No. of unique reflections | 4183 | 4236 | 9264 | 6375 |

| 2Θ max | 54.90 | 52.92 | 64.42 | 55.78 |

| Rint | 0.054 | 0.041 | 0.027 | 0.032 |

| No. of parameters (restraints) | 257(0) | 274(0) | 385(1) | 385(1) |

| Final R for data with I > 2σ(I) | 0.0454 | 0.0395 | 0.0475 | 0.0382 |

| wR for data with I > 2σ(I) | 0.1142 | 0.0855 | 0.1184 | 0.0967 |

| Goodness of fit | 1.091 | 1.037 | 1.035 | 1.014 |

2.6 Conversion of the diastereoisomers to the corresponding SP and RP O-alkyl methylphosphonate esters of CHMC (Fig. 1a)

Two hundred mg of either I-RPSC or I-SPSC were added to 10 ml of 1 M H2SO4 in either ethanol, n-propanol or i-propanol, and the mixture stirred at RT for 24 h to complete the reaction, as evidenced from the disappearance of the starting OP amidate 31P-nmr signal and the appearance of the new signal of the product. The alcoholysis medium was then vortexed with 100 ml CHCl3, and the organic layer was washed first with cold water (2x50 ml), and then with cold 2% Na2CO3 (20 ml). The organic solution was dried over Na2SO4, the solvent evaporated, and the residual oily material triturated with ethyl acetate to give 30–40 mg of solid material. The two optical isomers of the O-ethyl analog (Fig. 1a, SP-EMP-CHMC, and RP-EMP-CHMC) were recrystalized from ethyl acetate and displayed the same nmr characteristics: 31P (124.1 MHz, CDCl3), δ 29.0 (1H: 31P coupled; 9 lines). 1H (300 MHz, CDCl3), δ 7.72 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.35(dq, J=8.0, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (bs, 1H), 4.24 (m, 2H), 2.75 (s, 3H), 1. 72 (d, J=17.5 Hz, 3H, CH3-P), 1.35 (t, J= 7.0 Hz, 3H). It should be noted that the limited amounts of purified enantiomers of EMP-CHMC and the very low reading on the polarimeter precluded accurate determination of [α] D. However, it is clear that the individual enantiomers displayed negative and positive rotations.

The RP and SP enantiomers of the O-n-propyl methylphosphonate ester of CHMC (Fig. 1a, SP-nPrMP-CHMC, and RP-nPrMP-CHMC) were obtained as viscous oils, and could not be crystallized. The 31P- and 1H-nmr spectra of the two antipodes were identical: 31P (124.1 MHz, CDCl3), δ 31.8 (1H:31P coupled; 9 lines). 1H (300 MHz, CDCl3), δ 7.70 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dd., J=7.5, 0.5 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (bs, 1H), 4.15 (m, 2H), 2.75 (s, 3H), 1.75 (d, J=18 Hz, CH3-P), 1.70 (m, 2H), 0.95 (t, J=7.0 Hz). [α]D20, SP-nPrMP-CHMC = +8.6o (c=3.7, CHCl3)., RP- nPrMP-CHMC = −8.4o (c=2.5, CHCl3).

In the case of the O-isopropyl analog, due to lack of sufficient material only the I-RPSC was available to react with isopropanol, and the absolute configuration determined by X-ray crystallography verified, as predicted, the RP-iPrMP-CHMC antipode. The 31P- and 1H-nmr spectra of RP-iPrMP-CHMC were found identical to that of racemic iPrMP-CHMC which was prepared by the same protocol as described for racemic surrogates (see 2.2). 31P (121.4 MHz, CDCl3) δ 28.0 (1H:31P coupled: 8 lines, dq). 1H (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J= 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (bs,1H), 4.80 (m, 1H), 2.70 (s, 3H), 1.65 (d, J=16 Hz, CH3-P), 1.40 [d, J= 6 Hz, 3H, one methyl of -CH(CH3)2], 1.30 [d, J= 6.0 Hz, 3H, the 2nd methyl of -CH(CH3)2]. It should be noted that the two CH3 groups of isopropyl group are magnetically non-equivalent due to the pro-chirality of the carbon atom, –CH (CH3)2

2.7 Determination of Km and kcat. values for rePON1 variants

The enzymatic hydrolyses of the OP surrogates of nerve agents by purified rePON1 mutants were followed by monitoring the initial velocity of the release of the CHMC leaving group at 400 nm (in 50 mM Tris-1mM CaCl2, pH 8.0, 25oC). Data analysis was processed in accordance with the double reciprocal plot of Lineweaver-Burk using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0a, and assuming classical Michaelis-Menten behavior. Background non-specific hydrolysis of the CHMC-containing substrates was subtracted. kcat was calculated using a molar absorbance coefficient of 3.7x104 M−1cm−1 at 400 nm (pH 8.0) and a molecular weight of 40 kDa for rePON1 variants.

2.8 Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase

0.2–1.0 nM of either hAChE or TcAChE in 50 mM phosphate, pH 8.0, were incubated at 25oC with a ≥10-fold excess of OP, and the rate of loss of enzyme activity was monitored by 20–50-fold dilution of the inhibition mixture into Ellman’s reaction assay medium [20] containing 1 mM acetylthiocholine as substrate.

3.0 Results and Discussion

3.1 Stereo-specific synthesis via construction of pairs of diastereoisomers

The separated pair of diastereoisomers which was obtained by reacting CH3POCl2 in a one-pot synthesis with L-proline methyl ester, followed by reaction with CHMC (Fig. 1a), was found by X-ray diffraction to possess the same SC configuration at the chiral proline carbon. The SP and RP configurations at the phosphorous atom were established, and the purified diastereoisomers designated as I-SPSC and I-RPSC, respectively (Table 1). X-ray diffraction showed that reaction with either primary or secondary alcohols under acidic conditions leads to the formation of the SP enantiomer from I-SPSC, and of the RP isomer from I-RPSC. Similar conclusions with respect to the stereochemistry of the products of ethanolysis of homologous diastereoisomers were reached by Leader and Casida [21], who used 1H- and 31-P-nmr considerations to propose inversion of the configuration at the phosphorous center of the pesticide profenofos. The finding that the absolute configuration at the P atom of I-SPSC and I-RPSC was maintained in the EMP-CHMC SP and RP enantiomers is attributed to inversion at the phosphorus center that accompanied the displacement of the proline moiety and to the change in substituent priority that governs the assignment of the absolute configuration of atoms of a chiral molecule, due to the replacement of the P-N bond of the OP-bound proline by a P-O-alkyl moiety. Similarly, structural analysis by X-ray diffraction of the reaction product between I-RPSC and isopropanol resulted in RP-iPrMP-CHMC, which is consistent with the contention that inversion occurred during the replacement of the proline by an O-alkyl group, presumably via an SN2 substitution mechanism. No attempts were made to identify side products of the alcoholysis reaction.

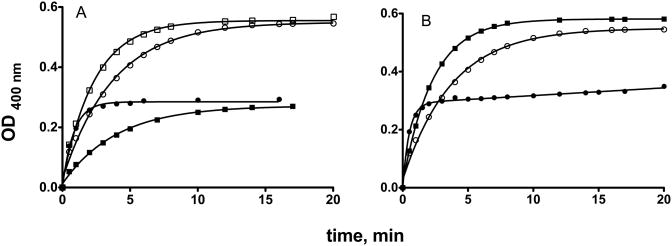

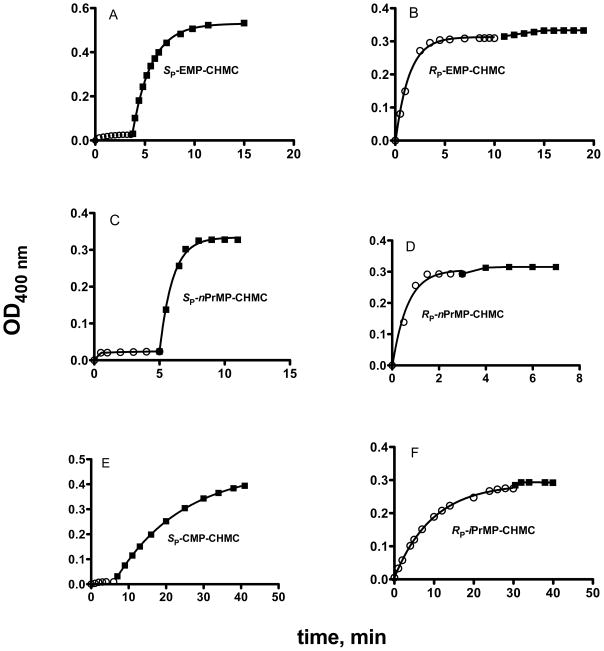

When the same reaction was repeated with n-propanol, the transformation of the I-SPSC and I-RPSC to the SP and RP enantiomers resulted in a viscous oil and X-ray crystallography could not be used to detemine the absolute configuration. However, production of the assumed SP and RP isomers, based on analogy with the stereochemical course of the reaction with ethanol and isopropanol was confirmed by use of a rePON1 mutant (3B3) that hydrolyzes almost exclusively the RP isomer, and of the 3D8 mutant that hydrolyzes both enantiomers. This is demonstrated in Fig. 2 that compares the stereo-selectivities of wt rePON1 and of 3B3 (Fig. 2A) with those of variants H115W and 3D8 (Fig. 2B) in hydrolyzing racemic EMP-CHMC. Fig.3 shows the optical purity of the various enantiomers. The OP-bound CHMC was released quantitavely (>95% of the calculated value of the stock solution) by NaF, in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A), while wt rePON1 and 3B3 released only half of the available OP-bound CHMC. Mutant H115W also displayed a marked preference towards the same isomer, presumably the RP enantiomer of the racemic EMP-CHMC; however, it also displayed an experimentally detectable reactivity on the second isomer (Fig. 2B). Mutant 3D8 clearly showed enhanced reactivity towards the wt-resistant enantiomer and, together with 3B3, was utilized to determine: (a) the optical purity of the SP and RP enantiomers, and (b) to verify the configuration of the assumed SP and Rp enantiomers of nPrMP-CHMC. Fig. 3 (panels A & B) shows the kinetic behavior of the X-ray-established SP and Rp enantiomers of EMP-CHMC in the presence of 3B3 and 3D8. Each isomer contains about 5% of the contaminating enantiomer. Similar time-course patterns and levels of optical purity were recorded for the deduced SP and Rp of nPrMP-CHMC (Fig 3C&D). Thus, results suggest that propanolysis of the two diastereoisomers was also accompanied by inversion. It is assumed that the minor presence of the counter isomer in each preparation stems from impurities in the parent diastereoisomers I-SPSC and I-RPSC, and is not due to racemization during the course of alcoholysis [21].

Fig.2.

Hydrolysis of 0.014 mM racemic EMP-CHMC. Panel A: □- □, 0.1 M NaF; ○-○, 0.05 M NaF; •-•, 0.03 μM wt rePON1; ▪- ▪, 0.012 μM 3B3. Panel B: ○-○, 0.05 M, NaF; ▪-▪, 0.048 μM 3D8; •-•, 0.035 μM H115W

Fig. 3.

Determination of the optical purity of the enantiomers of EMP-CHMC (Panels A & B) and of nPrMP-CHMC (Panels C & D) by use of mutants 3B3 (○-○) and 3D8 (▪-▪). The optical purities of SP-CMP-CHMC and RP-iPrMP-CHMC are illustrated in panels E and F, respectively. In all cases, 3D8 was added after termination of CHMC release in presence of 3B3. The latter hydrolyzes exclusively the RP isomer, whereas 3D8 hydrolyzes both the SP and RP enantiomers (Fig. 2B)

The structural analysis, together with results of the enzymic hydrolysis data, provided direct evidence for the marked preference of wt rePON1 and the H115W variant for the three RP isomers of the O-alkyl methylphosphonyl-CHMC analogs, regardless of the size of the alkyl group. Variant 3B3 displayed even greater stereo-specificity towards the RP enantiomers (Devi-Gupta et al., unpublished). Thus, assuming that the CH3, the P=O, and the CHMC groups of the tested stereoisomers are accommodated by the same binding regions at the active site, the various O-alkyl moieties of the RP isomers are probably projected towards the same relatively wide pocket that does not impose steric constraints on the alkyl residue. This conclusion is further supported by the kinetic data for hydrolysis of the cyclohexyl analog (see below).

3.2. Isolation of SP-CMP-CHMC by enzymic degradation of racemic CMP-CHMC

The free CHMC in SP-CMP-CHMC did not exceed 2% of the bound CHMC, and the contamination of SP-CMP-CHMC by the RP isomer, as judged by the release of CHMC in presence of 3B3, was ~ 3% (Fig. 3E).

The absolute configuration of the O-cyclohexyl analog isolated after partial hydrolysis of racemic CMP-CHMC by mutant 3B3 was shown by X-ray crystallography to conform to the SP configuration (Table 2). The SP was found to be an extremely poor substrate of wt rePON1 and of the 3B3 mutant, whereas the 3D8 mutant released the theoretical amount of CHMC quite rapidly (not shown). These results are consistent with the stereo-preferences of the two mutants as revealed from their reaction with the individual enatiomers of EMP-CHMC, nPrMP-CHMC, and iPrMP-CHMC.

Table 2.

Crystallographic data for Rp isomer of iPrMP-CHMC and SP enantiomer of CMP-CHMC

| Rp-iPrMP-CHMC | SP-CMP-CHMC | |

|---|---|---|

| Formula | 2(C15H16N1O5P) + O | C18H20N1O5P |

| Crystal description | Colorless needle | Colorless plate |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.80×0.30×0.10 | 0.50×0.40×0.10 |

| FW, gr mol−1 | 658.52 | 361.32 |

| Space group | C2 | P21 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| a, Å | 31.302(7) | 6.5200(5) |

| b, Å | 7.0663(14) | 12.9097(10) |

| c, Å | 28.358(6) | 10.5795(9) |

| α, ° | ||

| β, ° | 90.30(3) | 95.090(3) |

| γ, ° | ||

| Cell volume, Å3 | 6272(2) | 886.98(12) |

| Z | 8 | 2 |

| Density(calc, gr cm−3) | 1.395 | 1.353 |

| μ, mm−1 | 0.202 | 0.183 |

| No. of reflections | 15673 | 24739 |

| No. of unique | 9361 | 6818 |

| reflections | ||

| 2Θ max | 52.74 | 66.90 |

| Rint | 0.1339 | 0.028 |

| No. of parameters (restraints) | 846(73) | 228(1) |

| Final R for data with I > 2σ(I) | 0.0756 | 0.0327 |

| wR for data with I > 2σ(I) | 0.1855 | 0.0830 |

| Goodness of fit | 0.953 | 1.039 |

Hydrolysis induced by NaF showed that the SP-CMP-bound CHMC corresponds to >95% of the calculated value. SP-CMP-CHMC displayed high optical purity, with a low fluorescence background, which permitted meaningful screening of huge libraries for positive clones capable of hydrolyzing the toxic isomer of the OP surrogate both by use of a FACS protocol, and by monitoring the release of chromophore by lysates in a 96-well-plate format.

3.3 Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by the SP and RP enantiomers

For all the SP isomers acting on AChE, pseudo-first order inhibition rate constants (kobs) were obtained by fitting the data points for residual activity to a mono-exponential decay function, and the bimolecular rate constants for inhibition (ki) were determined from the slopes of the linear plots of kobs vs. inhibitor concentration. In the case of the RP isomers, that were contaminated with ~ 5% of the more potent anti-AChE, the SP form, the experimental data were best fitted to a bi-exponential decay curve with the constraint of 5% and 95% amplitude distribution for the SP and RP isomers, respectively (not shown)..

The ki values for the inhibition of hAChE and TcAChE by the various optical isomers are summarized in Table 3. The faster rates of inhibition by the SP isomers of the O-ethyl and On-propyl analogs, compared to their RP enantiomers, confirmed the previously deduced SP configuration of the toxic isomers of nerve agents [10].

Table 3.

Bimolecular rate constants (ki) for the inhibition of hAChE and TcAChE

| Enantiomer | human AChE (ki, x107 M−1 min−1)a | Torpedo AChE (ki,x107 M−1 min−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| Sp-EMP-CHMC | 2.80(SP/RP =23) | 21.0(SP/RP =11) |

| RP-EMP-CHMCb | 0.12 | 1.9 |

| SP-nPrMP-CHMC | 15.8(SP/RP =26) | 77.0(SP/RP =97) |

| RP-nPrMP-CHMCb | 0.61 | 0.79 |

| SP-CMP-CHMC | 8.2 | 3.7 |

S.D. < 20% (n=3–5)

Figures corrected for the contamination with 5% SP isomer

The X-ray-determined absolute configuration of the O-alkyl methylphosphonates provides an important set of nerve agent surrogates that serve to unequivocally establish the stereo-preference of AChEs. The simultaneous binding of the CH3-P, O-alkyl-P, and the P=O groups in the acyl pocket, the alkoxy binding site, and the oxyanion hole, respectively, [11], dictates the preferred accommodation of the SP configuration that stabilizes both the ground-state complex between the approaching inhibitor and the chiral AChE (analogous to the Michaelis-Menten complex), and the transition state that facilitates the inhibition reaction. In all these cases the leaving group is oriented towards the opening of the active-site gorge, ready to be expelled by an in-line attack of the active-site serine [11]. Thus, for O-alkyl methylphosphonates with a wide variety of leaving groups such as fluoride (G agents), N, N-dialkylaminoiethanthiolo (V-agents), and the bulky leaving group of the CHMC surrogates, the SP enantiomer is the more potent anti-AChE form.

TcAChE was found significantly more sensitive than hAChE to inhibition by the SP enantiomers of the ethyl (EMP) and the n-propyl (nPrMP) esters of CHMC, and also by the RP-EMP-CHMC isomer, but not by SP-CMP-CHMC. These findings contribute new data to an accumulated body of evidence showing significant differences in the susceptibilities of the two AChEs to various inhibitors [22]. The kinetics of inhibition of hAChE and TcAChE by the O-i-propyl enantiomers will be reported elsewhere after optically pure SP-iPrMP-CHMC is obtained.

3. 4 Enzymatic hydrolysis of the SP and RP enantiomers by rePON1 variants

The kinetic parameters for the reaction of wt rePON1 and mutant H115W with the enantiomers of EMP-CHMC and nPrMP-CHMC are summarized in Table 4. In the case of the SP enantiomer that contains about 3–5% of the preferred substrate with the RP configuration, the data points for the Lineweaver-Burke plots were taken after 5–10 min of pre-incubation so as to minimize a possible contribution by the RP contaminant, and the analytical concentration of the remaining SP substrate (~95%) was adjusted on the basis of the released chromophore monitored at 400 nm. Compared to the relatively inactive SP isomers, the two RP enantiomers were found to be very good substrates for both the wt and the H115W variants of rePON1, with kcat values of 300–700 min−1 and kcat/Km values of 3.7–5.6 x107 M−1min−1. It should be noted that for the O-alkyl methylphosphonate series the stereo-specificity is not affected by the size of the O-alkyl group, nor by the size and electronic features of the leaving group, as can be judged from the fact that the same preferences are reported for the corresponding fluoridates [6-9]. Results are the first direct structural evidence, based on X-ray crystallography, that wt mammalian paraoxonases hydrolyze preferentially the RP-CHMC surrogates of nerve agents. Similar conclusions were reported with respect to the reaction of bacterial PTE with the RP isomers of p-nitrophenolate analogs of nerve agents [6].

Table 4.

kcat (min−1) and kcat/Km (x106 M−1min−1) for the hydrolysis of the SP and RP enantiomers of EMP- and nPrMP-CHMC, and for SP-CMP-CHMC. by rePON1 variants

| wt (G3C9) | H115W | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | kcat/Km | kcat | kcat/Km | |

| SP-EMP-CHMC | 9 | 0.063 | 30 | 0.4 |

| RP-EMP-CHMC | 703 | 37 | 33 | 46 |

| RP/SP | 587 | 115 | ||

| SP-nPrMP-CHMC | 110 | 0.82 | 388 | 1.5 |

| RP-nPrMP-CHMC | 297 | 56 | 10 | 53 |

| RP/SP | 68 | 35 | ||

| SP-CMP-CHMC | NDa | <0.002b | NDa | ~0.005b |

Not determined. Km is estimated at > 1 mM

Estimates based on the assay limits of the chromophore absorption at 400 nm and the protein concentration in the reaction mixture.

Table 4 also demonstrates the appearance of a variant (mutant H115W) that is characterized by 2- to 6-fold enhanced kcat/Km values for hydrolysis of the SP isomers of O-ethyl, O-n-propyl, and O-cyclohexyl analogs as compared to the wt enzyme. The fact that H115W displays accelerated hydrolysis of the SP isomer, regardless of the size of the O-alkyl moiety, suggests that directed evolution can readily utilize lead variants, such as H115W, for development of mutants capable of effective hydrolysis of the toxic isomers of nerve agents. The use of the SP isomers to construct a repertoire of mutants with kcat/Km>1x107 M−1min−1 when reacting both with nerve agents analogs and with the actual ‘live agents’ will be published elsewhere (Devi-Gupta et al., ms in preparation).

4. Conclusions

The individual stereoisomers of several O-alkyl methylphosphonylated coumarin analogs of nerve agents were prepared by a stereo-specific synthesis protocol, and by an enzymatic procedure that utilized the racemic mixture of the fluorogenic surrogates and a rePON1 mutant that hydrolyze preferentially the RP isomer. The high enantiomeric purity, and the low level of free chromophore suggests that the SP chiral analogs of nerve agents are suitable for screening of large rePON1 libraries for variants capable of hydrolyzing the toxic isomers of nerve agents. Of particular importance is the successful alcoholysis of the pair of diastereoisomers with a secondary alcohol, such as i-propanol, that opens the way to the synthesis of chiral O-pinacolyl and O-cyclohexyl analogs of soman and cyclosarin, respectively. The X-ray crystal structures, together with in vitro measurements of the rates of inhibition of AChE, and of the proficiency (kcat/Km) of rePON1 variants, confirmed that the SP isomers as the more potent anti-AChE agents, and the corresponding RP antipodes as the preferred substrates of wt rePON1. The moderate, yet detectable, enhancement of kcat/Km of H115W, relative to the wt rePON1, suggests that directed evolution of rePON1 lead mutants such as H115W, together with designed molecular engineering guided by the 3D structures of rePON1 variants, and kcat and Km values, is likely to evolve rePON1 variants with catalytic efficacy that will qualify them as potential drug candidate for prophylactic treatment of nerve agent intoxication.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by the NIH CounterACT Program (1U54NS058183) and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA 1-07-C-0024) to DST and JLS is gratefully acknowledged

Abbreviations

- OPH

organophosphate hydrolase

- PTE

phosphotriesterase

- PON

paraoxonases

- CHMC

3-cyano-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin

- hAChE

recombinant human AChE

- TcAChE

Torpedo californica AChE

- EMP

O-ethyl methylphosphonyl

- nPrMP

O-n-propyl methylphosphonyl

- iPrMP

O-i-propyl methylphosphonyl

- CMP

O-cyclohexyl methylphosphonyl

Footnotes

6. Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests. (It should be noted that a patent application was submitted with respect to the generation of the rePON1 variants mentioned in this paper.)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ashani Y, Rothschild N, Segall Y, Levanon D, Raveh L. Prophylaxis against organophosphate poisoning by an enzyme hydrolyzing organophosphorus compounds in mice. Life Sci. 1991;49:367–374. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90444-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raveh L, Segall Y, Leader H, Rothschild N, Levanon D, Ashani Y. Protection against tabun intoxication in mice by prophylaxis with an enzyme hydrolyzing organophosphate esters. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44:397–400. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90028-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird SB, Sutherland TD, Gresham C, Oakeshott J, Scott C, Eddleston M. OpdA, a bacterial organophosphorus hydrolase, prevents lethality in rats after poisoning with highly toxic organophosphorus pesticides. Toxicology. 2008;247:88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens RC, Suzuki SM, Cole TB, Park SS, Richter RJ, Furlong CE. Engineered recombinant human paraoxonase 1 (rHuPON1) purified from Escherichia coli protects against organophosphate poisoning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12780–12784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805865105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaidukov L, Bar D, Yacobson S, Naftali E, Kaufman O, Tabakman R, Tawfik DS, Levy-Nissenbaum E. In vivo administration of BL-3050: highly stable engineered PON1-HDL complexes. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2009;18 doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-9-18. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li WS, Lum KT, Chen-Goodspeed M, Sogorb MA, Raushel F. Stereoselective detoxification of chiral sarin and soman analogues by phosphotriesterase. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2083–2091. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey SP, Kolakowski JE, Cheng TC, Rastogi VP, Reiff LP, DeFrank JJ, Raushel FM, Hill C. Stereo-specificity in the enzymatic hydrolysis of cyclosarin (GF) Enzyme and Microbial Technol. 2005;37:547–555. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amitai G, Gaidukov L, Adani R, Yishai S, Yacov G, Kushnir M, Teitelboim S, Lindenbaum M, Bel P, Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS, Meshulam H. Enhanced stereoselective hydrolysis of toxic organophosphates by directly evolved variants of mammalian serum paraoxonase. FEBS J. 2006;273:1906–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeung DT, Smith JR, Sweeney RE, Lenz DE, Cerasoli DM. Direct detection of stereospecific soman hydrolysis by wild-type human serum paraoxonases. FEBS J. 2007;274:1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benschop HP, de Jong LP. Nerve agent stereoisomers: analysis, isolation, and toxicology. Accnts Chem Res. 1998;21:368–374. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanson B, Nachon F, Colletier JP, Froment MT, Toker L, Greenblatt HM, Sussman JL, Ashani Y, Masson P, Silman I, Weik M. Crystallographic snapshots of nonaged and aged conjugates of soman with acetylcholinesterase and of a ternary complex of the aged conjugate with pralidoxime. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7593–7603. doi: 10.1021/jm900433t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timperley CM, Casey KE, Notman S, Sellers DJ, Williams NE, Williams NH, Williams GR. Synthesis and anti-cholinesterase activity of some new fluorogenic analogues of organophosphorus nerve agents. J Fluorine Chem. 2006;127:1554–1563. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amitai G, Adani R, Yacov G, Yishay S, Teitelboim S, Tveria L, Limanovich O, Kushnir M, Meshulam H. Asymmetric fluorogenic organophosphates for the development of active organophosphate hydrolases with reversed stereo-selectivity. Toxicology. 2007;233:187–98. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blum MM, Timely CM, Williams GR, Thiemann H, Worek F. Inhibitory potency against human acetylcholinesterase and enzymatic hydrolysis of fluorogenic nerve agent mimics by human paraoxonase 1 and squid isopropyl fluorophosphates. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5216–5224. doi: 10.1021/bi702222x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modritzer K, Miller RE. A convenient one-step, high–yield preparation of methylphosphonyl dichloride from dimethyl methylphosphonate. Syn React Inorg Metal-Org Chem. 1974;4:415–427. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Varon L, Toker L, Futerman AH, Silman I. Purification and crystallization of a dimeric form of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica subsequent to solubilization with phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. J Mol Biol. 1988;205:821–823. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aharoni A, Gaidukov L, Yagur S, Toker L, Silman I, Tawfik DS. Directed evolution of mammalian paraoxonases PON1 and PON3 for bacterial expression and catalytic specialization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:482–487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536901100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS. The histidine 115-histidine 134 dyad mediates the lactonase activity of mammalian serum paraoxonases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7649–7656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta RD, Tawfik DS. Directed enzyme evolution via small and effective neutral drift libraries. Nature Methods. 2008;5:939–942. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leader H, Casida JE. Resolution and biological activity of the chiral isomers of O-(4-bromo-2-chlorophenyl) O-ethyl S-propyl phosphorothiolate (profenofos insecticide) J Agr Food Chem. 1982;30:546–551. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bar-On P, Millard CB, Harel M, Dvir H, Enz A, Sussman JL, Silman I. Kinetic and structural studies on the interaction of cholinesterases with the anti-Alzheimer drug rivastigmine. Biochemistry. 2002;19:3555–3564. doi: 10.1021/bi020016x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]