Abstract

Cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, as well as proteins cooperating with them are responsible for cell cycle regulation which is crucial for normal development, injury repair, and tumorigenesis. D-type cyclins regulate G1 cell cycle progression by enhancing the activities of cyclin-dependent kinases, and their expression is frequently altered in tumors. Disturbances in cyclin expression were also reported in melanocytic skin lesions. The objective of the study was to evaluate the expression of cyclins D1 and D3 in common, dysplastic, and malignant melanocytic skin lesions. Forty-eight melanocytic skin lesions including common nevi (10), dysplastic nevi (24), and melanomas (14) were diagnosed by dermoscopy and excised. Expression of cyclin D1 and D3 was detected by immunohistochemistry and quantified as percentage of immunostained cell nuclei in each sample. In normal skin, expression of cyclins D1 and D3 was not detected. The mean percentage of cyclin D1-positive nuclei was 7.75% for melanoma samples, 5% for dysplastic nevi samples, and 0.34% for common nevi samples. For cyclin D3, the respective values were 17.8, 6.4, and 1.8%. Statistically significant differences in cyclin D1 expression were observed between melanomas and common nevi as well as between dysplastic and common nevi (p = 0.0001), but not between melanomas and dysplastic nevi. Cyclin D3 expression revealed significant differences between all investigated lesion types (p = 0.0000). The mean cyclin D1 and D3 scores of melanomas with Breslow thickness <1 mm and >1 mm were not significantly different. G1/S abnormalities are crucial for the progression of malignant melanoma, and enhanced cyclin D1 and D3 expression leading to increased melanocyte proliferation is observed in both melanoma and dysplastic nevi. In histopathologically ambiguous cases, lower cyclin D3 expression in dysplastic nevi can be a diagnostic marker for that lesion type.

Keywords: Cyclin D1, Cyclin D3, Dermoscopy, Melanocytic skin lesions

Introduction

The accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of melanocytic skin lesion is limited. Conventional clinical diagnosis of melanoma based on ABCD criteria (A asymmetry, B irregular borders, C various colors, D diameter >6 mm) is reliable only in approximately 60% of cases and excludes small melanomas (<6 mm). In addition, very early melanomas may have a regular shape and homogeneous color [1, 3, 13, 14]. Dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy, surface microscopy, and dermatoscopy) allows the identification of common and dysplastic nevi and also increases the diagnostic accuracy in cases of malignant melanomas [4, 7, 25, 26]. Its value in early and differential diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma has been clearly established by two independent meta-analyses, and efficient diagnostic algorithms have been published [6, 15]. Although dermoscopy has been introduced worldwide, it does not include evaluation of lesions at cellular level, which could enhance diagnostic accuracy for melanocytic skin lesions [13].

The regulation of cell proliferation is crucial for normal development, pathophysiological responses to injury, and tumorigenesis. Progression through the cell cycle is controlled by cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, and inhibitory proteins. D-type cyclins (D1 and D3) are the first cyclins to be expressed in the G1 phase and bound to their kinases CDK4 and CDK6. They play a major role in progression through the G1 restriction point [10, 12, 20] by regulating the function of pRb (retinoblastoma protein), which in its hypophosphorylated form (the functionally active form) can arrest cell cycle in G1 [12].

The role of cyclin D1 in the development, progression, and prognosis of melanomas is controversial. Some authors reported no difference in its expression in nevi and melanomas, whereas others showed overexpression of this protein in melanomas [10, 20]. Cyclin D3 is an important regulator of melanoma G1-S cycle progression. Its expression in melanoma cells can be readily detected by immunohistochemistry and is associated with poor prognosis [22].

It was proved that cyclin D1 increases cell growth potential and has no influence on cell differentiation [19]. Recent data suggest that cyclin D1 could be a marker of dysplastic skin lesions as it was overexpressed within the dermal–epidermal junction and/or papillary dermis in dysplastic nevi [9]. Cyclin D3, on the other hand, has been shown to have a dual function in proliferation and differentiation [17], and cyclin D3-positive cells were present throughout the lesion in most malignant melanomas, showing a close association between its expression and proliferation in superficial spreading melanomas [10].

The clinical and histopathological features allow to discriminate common nevi from melanomas; however, discrimination between dysplastic nevi and melanomas can be sometimes problematic, and the histologic criteria for diagnosis of the former are still disputed [11]. Hence, in doubtful cases, an additional diagnostic marker would be helpful. Studies of cyclin expression compared melanocytic nevi and melanomas [10, 12], but dysplastic nevi were not included in the analysis as a separate group. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate cyclin D1 and D3 expression in three groups of melanocytic lesions: common nevi, dysplastic nevi, and malignant melanomas and determine whether it could serve as a diagnostic marker in histologically uncertain lesions.

Materials and methods

Dermoscopy

Forty-eight melanocytic skin lesions were collected from patients at the Department of Dermatology, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University in May 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient following the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. The lesions were diagnosed by dermoscopy using Minolta Derlite photodermoscope. Surgical excision of melanocytic skin lesions for histopathologic evaluation is recommended when the lesion shows one of the following clinical or dermoscopic features: (1) benign dermal papillomatous nevus located in highly traumatic area, (2) the presence of two out of three criteria of the 3-point checklist as a screening method (1 asymmetry, 2 atypical network, and 3 blue-white structures) [25]), (3) the presence of one or two melanoma-specific local criteria (atypical pigment network, irregular streaks, irregular dots and globules, irregular blotches, and blue-white structures). Lesions fulfilling the above criteria were excised; in case of melanomas, the margin of normal skin (used as control samples) depended on the thickness of melanoma: for melanoma in situ—5 mm; for thickness <2 mm—1 cm; and for thickness >2 mm—2 cm. The samples collected were common nevi (10), dysplastic nevi (24), and melanomas (14), including nodular melanoma (7), superficial spreading melanoma (3), and lentigo maligna melanoma (4). Among the melanoma cases, six samples were defined as “thin”, with Breslow thickness <1 mm, and eight samples as “thick” with Breslow thickness >1 mm. None of the patients with melanoma had metastases.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

The excised samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. All lesions were evaluated using the standard histopathologic criteria (hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections) to reconfirm the diagnosis. The histologic identification of dysplastic nevi was based on the presence of junctional nests of melanocytes often exhibiting large pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli, uniformly elongated rete ridges, and lymphocytic infiltrations [11].

In three cases, dermoscopic diagnosis was altered after histopathologic evaluation: two dermoscopically diagnosed melanomas were identified as dysplastic nevi, and one dermoscopically diagnosed superficial spreading melanoma was identified as lentigo maligna melanoma.

For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized 6 μm sections were subjected to antigen retrieval using 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (5 min preincubation followed by 9 min in microwave oven, 160 W, at 100°C, and 30 min in vapor bath at 80°C). Next the sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary mouse antibodies against cyclin D1 or D3, followed by secondary goat anti-mouse Cy3-conjugated antibody. The antibodies were diluted according to manufacturer’s recommendations (Table 1). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Only nuclear immunostaining was scored as positive. In each sample, cyclin expression was assessed as percentage of cyclin-positive nuclei in the examined lesion. Microscopic examination, digital imaging of sections, and image analysis were carried out using Olympus BX-50 bright field/epifluorescence microscope equipped with DP-71 camera (Olympus, Japan) and PC-based image analysis software (AnalySIS-FIVE®, Soft Imaging System GmbH, Münster, Germany).

Table 1.

Antibodies used in the study

| Antibody against | Supplier | Code | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary antibodies | |||

| Cyclin D1 | Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, UK | NCL-CYCLIN D1 | 1:20 |

| Cyclin D3 | Novocastra Laboratories Ltd., Newcastle, UK | NCL-CYCLIN D3 | 1:20 |

| Secondary antibodies | |||

| Goat anti-mouse, Cy-3-conjugated | Jackson IR, West Grove, PA, USA | 115-165-146 | 1:400 |

Statistical analysis

The relationship between expression of cyclins and the type of melanocytic skin lesion (common nevi, dysplastic nevi, melanoma) was evaluated by nonparametric ANOVA rank Kruskal–Wallis test with p < 0.05 as condition for statistical significance.

Results

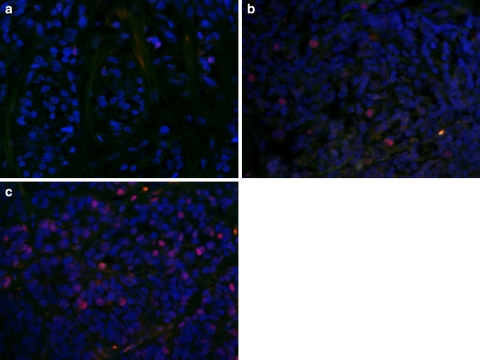

In normal skin, the expression of cyclins D1 and D3 was not detected. In melanocytic lesions, immunostaining was observed in cell nuclei, with some cells also exhibiting very weak cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 1). In common nevi, cyclin D1 and D3 immunostaining was observed mainly in cells located near the dermal–epidermal junction, whereas dysplastic nevi and melanomas exhibited a uniform distribution of cyclin-positive cells.

Fig. 1.

Micrographs showing cyclin D3 expression (dim red nuclear immunofluorescence) in common nevus (a), dysplastic nevus (b), and melanoma (c). Note weak signals emitted by three nuclei in common nevus and gradually increasing number of immunopositive nuclei in dysplastic nevus and melanoma. DAPI counterstaining of cell nuclei, bright orange nonspecific fluorescence of red blood cells. Original magnification ×400

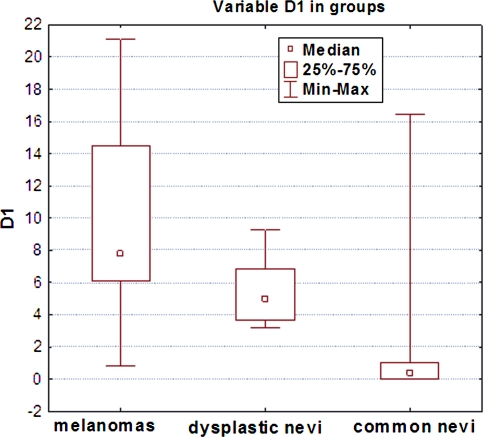

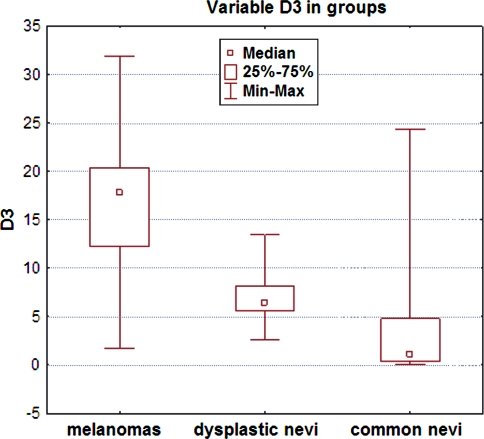

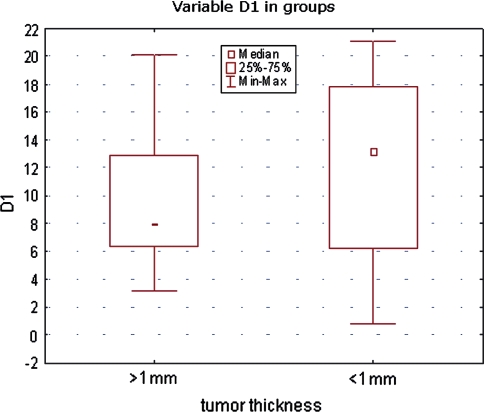

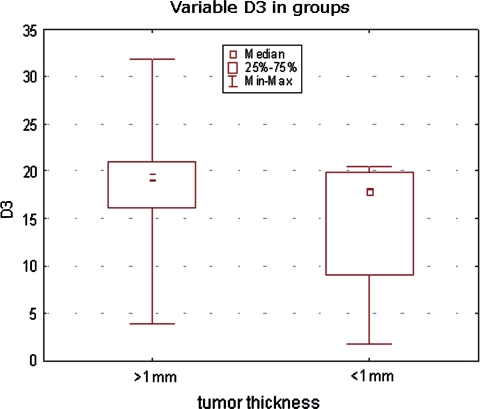

All investigated lesion samples showed expression of both cyclins. The mean percentage of cyclin D1-positive nuclei in melanomas, dysplastic nevi, and common nevi were 7.75, 5, and 0.34%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for cyclin D3 were 17.8, 6.4, and 1.08% (Table 2). Scoring data are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Statistically significant differences in cyclin D1 expression were observed between melanomas and common nevi and between dysplastic and common nevi (p = 0.0001), but not between dysplastic nevi and melanomas. Significant differences in cyclin D3 expression were observed between all lesion types: between melanomas and dysplastic nevi, between melanomas and common nevi and between dysplastic and common nevi (p = 0.0000; Table 2). The mean cyclin D1 and D3 scores of melanomas with Breslow thickness <1 mm were not significantly different from those of melanomas with Breslow thickness >1 mm (Figs. 4, 5).

Table 2.

Differences in cyclin D1 and D3 expression in melanocytic skin lesion

| Cyclin D1 | Melanomas R (7.75%) | Dysplastic nevi R (5%) | Common nevi R (0.34%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanomas | 1.969736 | 4.322768* | |

| Dysplastic nevi | 1.969736 | 2.995276* | |

| Common nevi | 4.322768* | 2.995276* |

| Cyclin D3 | Melanomas R (17.8%) | Dysplastic nevi R (6.4%) | Common nevi R (1.08%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanomas | 2.739677* | 4.478033* | |

| Dysplastic nevi | 2.739677* | 2.478140* | |

| Common nevi | 4.478033* | 2.478140* |

Cyclin D1: Kruskal–Wallis test: H (2, N = 48) = 18,77577, * significant, p = 0.0001

Cyclin D3: Kruskal–Wallis test: H (2, N = 48) = 20,32182, * significant, p = 0.0000

R mean percentage of immunostained cell nuclei

Fig. 2.

Cyclin D1 expression (percentage of immunostained cell nuclei) in melanocytic lesions

Fig. 3.

Cyclin D3 expression (percentage of immunostained cell nuclei) in melanocytic lesions

Fig. 4.

Cyclin D1 expression (percentage of immunostained cell nuclei) in melanomas according to tumor thickness

Fig. 5.

Cyclin D3 expression (percentage of immunostained cell nuclei) in melanomas according to tumor thickness

Discussion

In the present study, dermoscopy was employed to identify melanocytic skin lesions: common nevi, dysplastic nevi, and melanomas. We excised common nevi only if they were located in a highly traumatic area; patients were worried about their possible malignant transformation and insisted on their removal. Since the dysplastic nevi can be an intermediate step in tumor progression from common acquired melanocytic nevi to melanomas [2, 21], we excised them in cases when the dermoscopic appearance of the nevus did not allow to exclude melanoma with certainty.

In the three types of melanocytic skin lesions, immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the expression of cyclins D1 and D3. These cyclins, belonging to G1 cyclin family, are important for the passage of cells through the G1 phase into the S phase. We found the same expression pattern for both cyclins: expression was the highest in melanomas, the lowest in the common nevi, and intermediate in the dysplastic nevi, with all differences statistically significant except that between melanomas and dysplastic nevi for cyclin D1. Coordinated expression of both cyclins in dysplastic nevi and malignant tumors indicates that more than one D-type cyclin may be involved in tumor development.

Although no cyclin D1 expression could be detected in normal skin areas, we observed very few (0.34%) cyclin D1-positive cell nuclei in common nevi, in contrast to data reported by other authors who failed to find cyclin D1 expression in any common nevi [10]. Cyclin D1-positive cells were mostly located close to the dermal–epidermal junction, which corresponds to the observations of Stefanaki et al. [23] that common nevi shows either rare cyclin D1 positivity or a zonal expression pattern. This is quite distinct from melanomas which display diffuse cyclin D1 expression.

Previous studies have demonstrated various abnormalities in cyclin D1 and D3 expression in sporadic and familial melanomas [10, 12, 20, 24]. Cyclin D1 was observed to be recurrently overexpressed in melanomas, and its downregulation had a significant impact on melanoma cell growth [23]. We found significantly higher cyclin D1 expression in melanomas compared with common nevi, suggesting that cyclin D1 may play a role in the development of the malignant phenotype. Some authors reported the same relationship between common nevi and malignant melanocytic tumors, but others found no significant differences in the expression of cyclin D1 between those two groups [12, 20].

Cyclin D3 expression is required for efficient G1-S cell cycle progression, proliferation, and differentiation of melanocytes [5, 18, 22]. We found significantly higher cyclin D3 expression in melanomas as compared with dysplastic nevi. In case of cyclin D1, the difference also existed, but did not reach the level of significance. However, dysplastic nevi revealed significantly higher expression of both cyclins as compared with common nevi. It corresponds to results reported by Ewanowich et al. [9] who found overexpression of cyclin D1, especially in the region of epidermal–dermal junction. Enhanced cyclin expression in dysplastic nevi supports the view that cyclins are activated during the transition from benign to malignant phenotype of melanocytic skin lesion, and that dysplastic nevi represents an intermediate stage in this process. Our findings also suggest that cyclin D3 expression could be a marker for dysplastic melanocytic lesions in histopathologically ambiguous lesions, being significantly lower than in melanomas.

No relationship between thickness of melanoma and cyclin D1 and D3 expression observed in the present study seems to be a controversial finding. In case of cyclin D1, it remains in agreement with previous data reported in the literature [12, 20] although, in a recent study, de Sa et al. [8] demonstrated higher expression of cyclin D1 in thin superficial spreading melanomas as compared to thick ones. In case of cyclin D3, the results of other studies are discrepant: its expression was found to be higher in thicker superficial spreading melanomas, while the opposite relation was observed in nodular melanomas [10]. Jørgensen et al. [16] reported an association between cyclin D3 expression, cell proliferation, and disease progression in superficial spreading melanomas, and also observed higher expression being significantly associated with the thickness of primary tumors. We could not find any significant association between melanoma thickness and cyclin expression, possibly because of relatively small number of melanoma samples.

In summary, the present study has confirmed that G1/S abnormalities are crucial in the progression of melanocytic skin lesions, and that deregulation of cyclin D1 and D3 expression leading to increased melanocyte proliferation points to candidate proteins involved in melanoma genesis as possible therapeutic targets. Cyclin D3, showing significantly lower expression in dysplastic nevi than in melanomas, but higher than in common nevi, seems to be a suitable diagnostic marker for differentiation of these lesions in histologically doubtful cases.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by research grant 501/NKL/145/L from Jagiellonian University Medical College.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Alaibac M, Piaserico S, Rossi CR, Foletto M, Zacchello G, Carli P, Belloni-Fortina A. Eruptive melanocytic nevi in patients with renal allografts: report of 10 cases with dermoscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1020–1022. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(03)02482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annessi G, Cattaruzza MZ, Abeni D, Baliva G, Laurenza M, Macchini V, et al. Correlation between clinic atypia and histologic dysplasia in acquired melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:77–85. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, Argenziano G, Ruocco V. Impact of dermoscopy on the clinical management of pigmented skin lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:200–202. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(02)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argenziano G, Soyer HP. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions—a valuable tool for early diagnosis of melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:443–449. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bales ES, Dietrich C, Bandyopadhyay D, Schwahn DJ, Xu W, Didenko V, et al. High levels of expression of p27 and Cyclin E in invasive primary malignant melanomas. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:1039–1046. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, Stante M, Ricci L, Brunasso G, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:981–984. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celebi ME, Kingravi HA, Iyatomi H, Aslandogan YA, Stoecker WV, Moss RH, et al. Border detection in dermoscopy images using statistical region merging. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Sá BC, Fugimori ML, Ribeiro Kde C, Duprat Neto JP, Neves RI, Landman G. Proteins involved in pRb and p53 pathways are differentially expressed in thin and thick superficial spreading melanomas. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:135–141. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32831993f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ewanowich C, Brynes RK, Medeiros L, McCourty A, Lai R. Cyclin D1 expression in dysplastic nevi: an immunohistochemical study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:208–210. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0208-CDEIDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flørenes VA, Faye RS, Mælandsmo GM, Nesland JM, Holm R. Levels of cyclin D1 and D3 in malignant melanoma: deregulated cyclin D3 expression is associated with poor clinical outcome in superficial melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3614–3620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman RJ, Farber MJ, Warycha MA, Papathasis N, Miller MK, Heilman ER. The “dysplastic” nevus. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgieva J, Sinha P, Schadendorf D. Expression of cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases in human benign and malignant melanocytic lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:229–235. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerger A, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Samonigg H, Smolle J. In vivo confocal laser scanning microscopy in the diagnosis of melanocytic skin tumours. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:475–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Blum A, Wolf IH, Zalaudek I, Piccolo D, Kerl H, et al. Dermoscopic classification of Clark’s nevi (atypical melanocytic nevi) Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:255–258. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(02)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johr RH. Dermoscopy: alternative melanocytic algorithms-the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy, Menzies scoring method, and 7-point checklist. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:240–247. doi: 10.1016/S0738-081X(02)00236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jørgensen K, Holm R, Maelandsmo GM, Flørenes VA. Expression of activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 in malignant melanomas: relationship with clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5325–5341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiess M, Gill RM, Hamel PA. Expression of the positive regulator of cell cycle progression, cyclin D3, is induced during differentiation of myoblasts into quiescent myotubes. Oncogene. 1995;10:159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuźbicki L, Aładowicz E, Chwirot BW. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 expression in human melanomas and benign melanocytic skin lesions. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:435–444. doi: 10.1097/01.cmr.0000232290.61042.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang SB, Furihata M, Takeuchi T, Iwata J, Chen BK, Sonobe H, Ohtsuki Y. Overexpression of cyclin D1 in nonmelanocytic skin cancer. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:370–376. doi: 10.1007/s004280050461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramirez JA, Guitart J, Rao S, Diaz LK. Cyclin D1 expression in melanocytic lesion of the skin. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005;9:185–188. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripp JM, Kopf AW, Marghoob AA, Bart RS. Management of dysplastic nevi: a survey of fellows of the American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:674–682. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.121029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spofford LS, Abel EV, Boisvert-Adamo K, Alpin AE. Cyclin D3 expression in melanoma cells is regulated by adhesion-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling and contributes to G1-S progression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25644–25651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600197200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stefanaki C, Stefanaki K, Antoniou C, Argyrakos T, Stratigos A, Patereli A, Katsambas A. G1 cell cycle regulators in congenital melanocytic nevi. Comparison with acquired nevi and melanomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:799–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran TA, Ross JS, Carlson JA, Mihm MC. Mitotic cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases in melanocytic lesions. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1085–1090. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(98)90418-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weserhoff K, McCarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1016–1020. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zalaudek I, Argenziano G, Soyer HP. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy: an open internet study. Br J Dermatol. 2006;3:431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]