Abstract

Integrin receptors for cell adhesion to extracellular matrix have important roles in promoting tumor growth and progression. Integrin α3β1 is highly expressed in breast cancer cells where it is thought to promote invasion and metastasis; however, its roles in regulating malignant tumor cell behavior remain unclear. In the current study, we used short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) to show that suppression of α3β1 in a human breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231, leads to decreased tumorigenicity, reduced invasiveness, and decreased production of factors that stimulate endothelial cell migration. Real-time PCR revealed that suppression of α3β1 caused a dramatic reduction in expression of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene, which is frequently over-expressed in breast cancers and has been exploited as a therapeutic target. Decreased COX-2 was accompanied by reduced prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a major prostanoid produced downstream of COX-2 and an important effector of COX-2 signaling. shRNA-mediated suppression of COX-2 showed that it has a role in tumor cell invasion and crosstalk to endothelial cells. Furthermore, treatment with PGE2 restored these functions in α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells. These findings identify a role for α3β1 in regulating two properties of tumor cells that facilitate cancer progression: invasiveness and ability to stimulate endothelial cells. They also reveal a novel role for COX-2 as a downstream effector of α3β1 in tumor cells, thereby identifying α3β1 as a potential therapeutic target to inhibit breast cancer.

Keywords: integrin α3β1, cyclooxygenase-2, COX-2, breast cancer, invasion, MDA-MB-231

Introduction

Integrins are αβ cell surface receptors that mediate cell adhesion to extracellular matrix. In mammals, 18 α subunits and 8 β subunits can combine to form 24 different integrins with distinct, although often overlapping ligand-binding specificities [1]. Integrins expressed on tumor cells regulate many processes essential for cancer progression, including proliferation, survival, invasion, and metastasis [2-4]. Integrins are therefore attractive targets for anti-cancer therapeutics, which has lead to pre-clinical and clinical development of antagonists that target certain integrins [5]. However, most of these antagonists alter angiogenesis by targeting endothelial cell integrins [5, 6], and there remains a critical need to identify appropriate integrins to target on tumor cells.

Integrin α3β1 is expressed on many types of cancer cells and can regulate cell functions associated with malignancy (for reviews, see [7, 8]). Increased α3β1 has been correlated with breast cancer metastasis [9], and α3β1 regulates MMP-9 expression, invasion, and metastatic properties of squamous cell and breast carcinoma cells [9-11]. Two major extracellular matrix ligands for α3β1, laminin-332 and laminin-511, are often overexpressed in breast and other carcinomas and have been linked to invasion and metastasis [4, 12, 13]. In addition, α3β1 interactions with tetraspanins or other cell surface proteins can also regulate a range of cell functions (reviewed in [7, 8]).

Despite evidence that implicates α3β1 in carcinoma progression, little is known about its roles in tumorigenesis or how it regulates malignant cell behavior. To address this question, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to stably down-regulate α3β1 in the human breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231. We demonstrate that suppression of α3β1 leads to reduced tumor growth in vivo, reduced invasive potential, and decreased production of soluble factors that stimulate endothelial cell migration. Real-time PCR arrays revealed dramatically reduced expression of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene, which is frequently over-expressed in invasive breast cancers and a known promoter of tumor growth, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [14-21]. Subsequent analyses identified COX-2 as a mediator of certain tumor cell functions that are attributable to α3β1, including invasion and crosstalk to endothelial cells. As COX-2 has been pursued as a therapeutic target [17], our current findings identify α3β1 as a potential therapeutic target to inhibit breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

MDA-MB-231 cells (purchased from ATCC), or the variant line, 4175/TGL (a gift from Dr. Joan Massague’, Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY) [22], were cultured in DMEM (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% FBS (BioWhittaker), 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and L-glutamine (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from VEC Technologies (Troy, NY) and cultured as described [23].

shRNA-mediated gene suppression

MISSION™ lentiviral shRNA constructs (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were used to target the human Itga3 gene (5′-CCGGCGGATGAACATCACAGTGAAACTCGAGTTTCACTGTGATGTTCATCCGTTTTTG-3′) or the PGTS2 (COX2) gene (5′-CCGGCCAGGGCTCAAACATGATGTTCTCGAGAACATCATGTTTGAGCCCTGGTTTTTG-3′); a non-targeting shRNA was used as control (Sigma, catalog no. SHC002H). Lentiviruses were packaged in 293FT cells as described [11]. Viral supernatants were added to MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 to 48 hours, and stably transduced populations were selected in 10 μM puromycin. Separate experiments utilized a different α3-targeting shRNA to generate a distinct line of α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells, as described [24, 25]. For rescue experiments, RNAi effects were overcome by infecting cells with adenovirus that over-expresses human α3 (a gift from Dr. Martin Hemler, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) or lacZ, as described [11].

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen Corporation), then reverse transcribed using First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR reactions were carried out using PCR REDTaq ready mix (Sigma). Primers and conditions for amplication of α3, VEGF, or GAPDH were described previously [11, 26]. PCR conditions for COX-2 were as follows: forward primer, 5′-TACAAGCAGTGGCAAAGGC-3′; reverse primer, 5′-AGATCATCTCTGCCTGAGTATCTT-3′; 94°C, 30 seconds; 52°C, 30 seconds; 72°C, 60 seconds; 26 cycles. Signals were visualized using a Bio-Rad FlourS 2000 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Real-time PCR arrays

Total RNA was isolated using RT2 qPCR-Grade RNA Isolation Kit. cDNA was synthesized from 1.5 μg RNA using RT2 First Strand Kit (SABioscience, Frederick, MD). Real-Time PCR was performed using RT2 Profiler PCR array system according to manufacturer’s instructions (SABioscience) in an iCycler iQ Multicolor Detection System (Bio-Rad). Four separate experiments were performed using the Breast Cancer & Estrogen Receptor Signaling Pathways array and analyzed using Excel-based PCR Array Data Analysis Templates (SABioscience).

Immunoblots

Cells were lysed in Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and protein concentrations determined using BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Equal protein was assayed by immunoblot using rabbit anti-sera against α3 integrin (1:1000 dilution), COX-2 (1:200), or ERK (1:1000), followed by peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000). Anti-α3 was described previously [27]; other antisera were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Chemiluminescence was performed using SuperSignal Kit (Pierce).

Flow cytometry

MDA-MB-231 cells were trypsinized and incubated with 5 μg/ml anti-integrin monoclonal antibody (Chemicon, Billerica, MA): P1B5 (mouse anti-α3), P1D6 (mouse anti-α5), HB1.1 (mouse anti-β1), 3E1 (mouse anti-β4), GoH3 (rat anti-α6), or normal mouse IgG as control. Secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or goat anti-rat IgG (Molecular Probes Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde prior to flow cytometry on a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Data from 1×104 cells were analysed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc.).

Matrigel invasion

MDA-MB-231 derivatives (8×104 cells) were seeded onto Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel Invasion Chambers (8 μm pore; BD Biosciences) in complete medium and incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. Filters were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde, non-invading cells were removed, and invading cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml). Images were obtained using an Olympus inverted IX70 microscope equipped with a SensiCam digital camera (Cooke, Eugene, OR). Cells were counted from three random 10X fields/well using Image ProPlus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). We typically observed ~250-350 cells/field for control cells under these conditions. Cell invasion was quantified from three independent experiments in which results from duplicate samples were averaged.

Transwell migration of endothelial cells

Transwell migration was assayed as described [23]. Briefly, 5×104 serum-starved HUVECs were seeded onto transwell inserts (8 μm pore; Costar, Corning, NY) coated with 0.2% gelatin. Lower chambers contained serum-free MCDB-131 medium pre-conditioned for 24 hours by MDA-MB-231 variants in an 80:20 ratio with complete EGM-2 (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Unconditioned medium was used to establish baseline migration. After 4 hours of migration, cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet, non-migratory cells were removed, and migrated cells were stained with DAPI and quantified from three random fields/well, as described above. We typically observed 100-150 cells/field for control conditions. Data are from three separate experiments in which results from duplicate samples were averaged.

Cell growth in Matrigel

Single cell suspensions were prepared in Growth Factor-Reduced Matrigel (approximately 1.5 × 103 cells/40 μl), then submersed in growth medium. Colonies were photographed after 10 days, and mean colony diameter +/− S.E.M was determined for 60 to 100 random colonies for each MDA-MB-231 variant using ImageJ software, as described [25].

PGE2 assay

MDA-MB-231 variants (4 × 104 cells) were cultured on 24-well culture dishes in serum-free medium for 24 hours, then medium was collected and analyzed using the PGE2 EIA Kit-Monoclonal according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI). Data are from three separate experiments in which results from triplicate samples were averaged.

Xenografts in nude mice

For ectopic tumors, MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106 cells/200 μl) were injected subcutaneously into right flanks of NCR nude mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY). Tumor length (l) and width (w) were measured using a Vernier caliper, and mean tumor volume was calculated for each test group using the following formula: tumor volume = (w2 × l)/2. Tumorigenesis experiments in Supplementary Fig. S2B were performed as described [25]. For orthotopic tumors, 2 × 106 cells/50 μl (PBS:Matrigel) were injected into mammary fat pads of nude mice. Tumors were dissected after 35 days, weighed, and photographed. To assess angiogenesis, cryosections (10 μm) were stained with anti-CD31/PECAM-1 (BD Biosciences) followed by Alexa Flour 594 goat anti-rat IgG (Molecular Probes), and blood vessel density was calculated using IPLab (Scanalytics Inc., Fairfax, VA), as described [23]. For each test group, CD31 staining area (pixels/field) was averaged from ≥ ten 20X fields collected from three or more tumors. To assess proliferation, cryosections were stained with anti-Ki67 rabbit monoclonal antibody (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), followed by Alexa Flour 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes). Proliferation was estimated using IPLab to measure the proportion of DAPI-stained nuclei that also stained positive for Ki67. For each test group, data were averaged from ≥ six 10X fields collected from three or more tumors. Apoptosis was assessed using DeadEnd Fluorometric TUNEL System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Images were collected on a Nikon Eclipse 80i using a Spot camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Experiments performed at Albany Medical College were approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments at University of Birmingham were performed in accordance with institutional and national animal research guidelines.

RESULTS

Suppression of integrin α3β1 in breast cancer cells reduces tumorigenesis

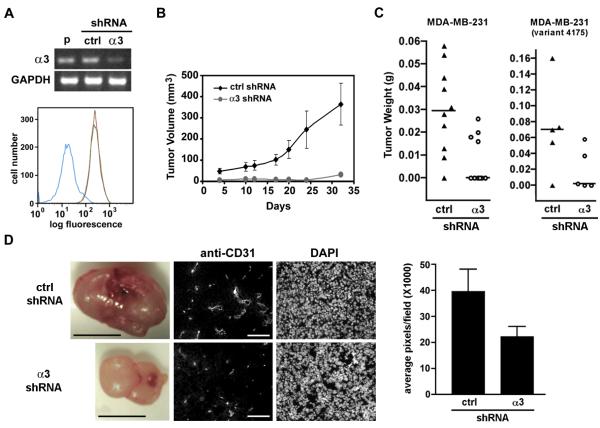

As an experimental model for our studies, we used shRNA to generate α3β1-deficient variants of the human breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231. Parental MDA-MB-231 cells expressed high levels of α3 mRNA and α3β1 on the cell surface (Fig. 1A), consistent with previous reports [9, 28]. α3 mRNA and α3β1 protein were efficiently suppressed in cells stably expressing an shRNA that targets human α3 [MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells], but not in cells expressing a non-targeting shRNA [MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells] (Fig. 1A). MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells also showed reduced surface expression of the β1 integrin subunit (Supplementary Fig. S1), the sole β subunit partner of α3 [1]. The relatively modest reduction in β1 may reflect dimerization of liberated β1 with other endogenous α subunits, as indicated by slightly increased α5β1 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Surface levels of α6 and β4 integrin subunits were slightly decreased in MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

α3β1 regulates tumorigenesis of breast cancer cells. (A) Parental MDA-MB-231 cells (p), MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells expressing control shRNA (ctrl), or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells expressing α3-targeting shRNA (α3) were assayed by RT-PCR for α3 mRNA or GAPDH mRNA (top panel). Flow cytometry (bottom panel) was performed to compare surface levels of α3β1 in parental cells (red line), MDA-MB-231/α3(+) (green line) or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells (blue line). (B) MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (ctrl shRNA) or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells (α3 shRNA) were injected subcutaneously into nude mice, and tumor growth was measured over 32 days. Data are mean +/− S.E.M; n≥6 mice per test group. (C) The same MDA-MB-231 derivatives (left graph, n=10 per test group), or similar derivatives of MDA-MB-231/4175 cells (right graph, n=5 per test group), were injected into mammary fat pads. Column scatter plots show tumor weights with median after 35 days for cells expressing control (triangles) or α3-targeting shRNA (circles). (D) Mammary tumors (left panels; scale bars, 50 mm) were cryosectioned and co-stained with anti-CD31 and DAPI (right panels; scale bars, 100μm). Graph shows relative anti-CD31 staining in tumors from cells expressing control or α3-targeting shRNA; mean +/− S.E.M; n≥10 fields from at least three separate tumors.

Following subcutaneous injection into nude mice, MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells showed dramatically reduced tumor growth over 32 days, compared with MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (Fig. 1B). α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells that were derived independently using a distinct α3-targeting shRNA also showed reduced tumorigenesis, as well as reduced colony formation in Matrigel (Supplementary Fig. S2), confirming that reduced tumor growth was neither an off-target effect of a particular α3-targeting shRNA, nor a peculiarity of a particular MDA-MB-231 lab stock. Importantly, similar results were obtained following orthotopic injection into mammary fat pads, where tumorigenesis was significantly reduced in MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells compared with MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (Fig. 1C, left graph; p=0.01, Mann-Whitney test). Mice injected with α3β1-deficient cells showed reduced tumor initiation (4/10) compared with mice injected with control cells (9/10), as well as smaller average tumor size. The same trend was observed in a variant of the MDA-MB-231 line, 4175, which grows more aggressively in the mammary fat pad (Fig. 1C, right graph) [22].

Ki67 immunostaining of tumor cryosections indicated a similar proportion of proliferative cells in each test group (Supplementary Fig. S3), and TUNEL-staining did not reveal differences in apoptosis (data not shown). While we cannot rule out the possibility of heterogeneous effects throughout the tumor, these findings indicate that α3β1-deficiency did not dramatically alter overall proliferation or survival of tumor cells, perhaps reflecting instead a role in early tumor cell interactions with stromal elements of the microenvironment that promote initial tumor growth. Consistently, MDA-MB-231/α3(−) tumors appeared less vascularized than MDA-MB-231/α3(+) tumors, and immunohistology with anti-CD31/PECAM confirmed ~2-fold reduction in blood vessel staining in the xenografts from α3-deficient cells (Fig. 1D). These results may reflect a pro-angiogenic role for α3β1 on tumor cells, similar to that which we recently described for α3β1 in the epidermis during wound healing [23].

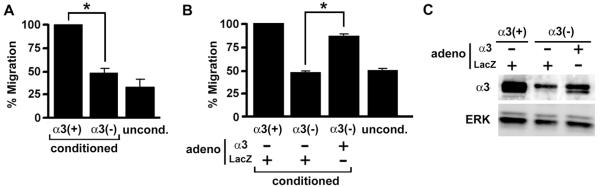

Integrin α3β1 on breast cancer cells promotes crosstalk to endothelial cells

To test if α3β1 can regulate the production of pro-angiogenic factors by tumor cells, we compared endothelial cell migration in response to factors secreted by MDA-MB-231 cells that express or lack α3β1. Endothelial cells (HUVECs) were seeded into the upper chambers of transwell filters, then conditioned culture media from MDA-MB-231/α3(+) or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells were added to the lower chambers and tested for effects on HUVEC migration. Medium conditioned by MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells stimulated HUVEC migration by ~3-fold over basal migration in response to unconditioned medium (Fig. 2A). In contrast, medium conditioned by MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells failed to induce a migratory response. Furthermore, HUVEC migration was enhanced in conditioned medium from MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells transduced with adenovirus expressing α3, while a control adenovirus did not rescue the response (Fig. 2B, C). These results indicate that α3β1 in breast cancer cells promotes secretion of factors that stimulate endothelial cell migration, an important component of angiogenesis.

Figure 2.

α3β1 in breast cancer cells regulates secretion of soluble factors that induce endothelial cell migration. (A) Transwell migration of HUVECs was compared in response to conditioned medium from MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (α3(+)) or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells (α3(−)); unconditioned medium (uncond.) was used to establish baseline migration. Graph shows HUVEC migration as percentage of that in cells treated with medium from MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells. (B) HUVEC migration was assayed as in (A), except that conditioned culture medium was collected from MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells, or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells transduced with adenovirus expressing α3 (adeno, α3) or LacZ (adeno, LacZ). For (A) and (B), data are mean +/− S.E.M; n=3 experiments; *p<0.004, two-tailed t-test. (C) Total lysates from MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells, or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells transduced with α3-expressing or LacZ-expressing adenovirus as indicated, were immunoblotted for α3 or ERK as a loading control.

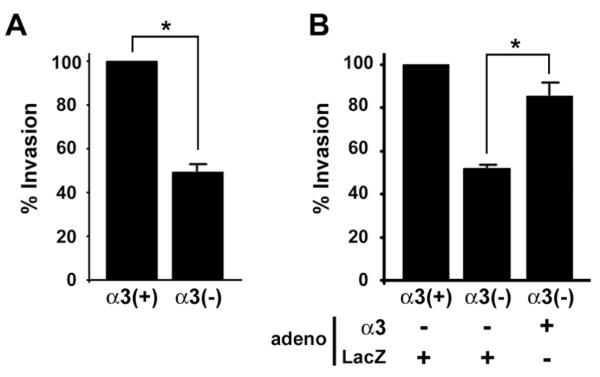

Suppression of integrin α3β1 reduces tumor cell invasion

Increased expression of α3β1 has been correlated with metastatic progression of human breast cancer [9]. Consistently, treatment of MDA-MB-231 cells with an antibody that blocks α3β1-mediated adhesion has been shown to reduce invasive potential [9] and arrest in the pulmonary vasculature [10]. However, integrin-blocking antibodies may inhibit only a subset of integrin functions, and some may even stimulate certain functions. Therefore, we next tested the effect of shRNA-mediated α3 suppression on cell invasion through Matrigel. MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells displayed significantly reduced invasion compared to the MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained using the independently derived α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells described above (data not shown). Exogenous α3 expression restored MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cell invasion (Fig. 3B), indicating that α3β1 promotes an invasive phenotype.

Figure 3.

α3β1 regulates breast cancer cell invasion. (A) Matrigel assays were performed to compare invasion between MDA-MB-231/α3(+) and MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells. Graph shows invasion as percentage of that in MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells; mean +/− S.E.M; n=3 experiments; *p<0.05, two-tailed t-test. (B) Matrigel invasion assays were performed as in (A), except that MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells were transduced with adenovirus that expresses either α3 (adeno, α3), or LacZ (adeno, LacZ). Data are presented as in (A); mean +/− S.E.M; n=3 experiments; *p<0.02, paired two-tailed t-test.

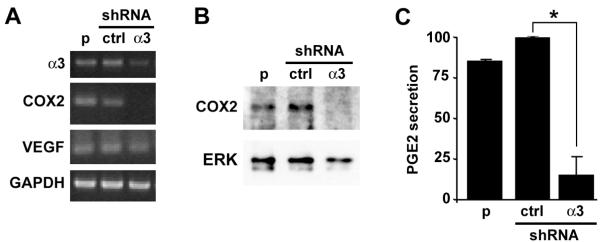

Integrin α3β1 is required for COX-2 gene expression

To screen for α3β1-dependent genes that may influence tumor cell function, we utilized the RT2 Profiler PCR Array (SABiosciences) to compare MDA-MB-231/α3(+) and MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells for expression of breast cancer-associated genes. Compiled results from four independent experiments identified several α3β1-dependent differences (Supplementary Table S1). The change of largest magnitude in the α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells was a ~74-fold decrease (p=0.001) in expression of the COX-2/PTGS2 gene. Clinical studies of COX-2 inhibitors have generated wide-spread interest in COX-2 as a therapeutic target [17], and roles for COX-2 in tumor growth, angiogenesis, and invasion are well established [15, 17-20]. We therefore focused our attention on potential roles for COX-2 in α3β1-mediated tumor cell functions.

RT-PCR and immunoblot confirmed that COX-2 mRNA and protein, respectively, were reduced substantially in MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells, compared with parental or control shRNA cells (Figs. 4A, B). As a control, we did not detect differences in VEGF mRNA by conventional (Fig. 4A) or real-time RT-PCR (Supplementary Table S1). Importantly, COX2 mRNA was also reduced in the independently derived α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells described above, indicating that this reduction was not an off-target RNAi effect (Supplementary Fig. S4). As an independent measure of COX-2 activity, we assessed MDA-MB-231 culture medium for levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a pro-tumorigenic prostanoid that is produced downstream of COX-2 [17]. As predicted, PGE2 levels were decreased substantially in conditioned medium from MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells, compared with MDA-MB-231/α3(+) or parental cells (Fig. 4C). These findings identify COX-2 as a potential mediator of pro-tumorigenic α3β1 functions.

Figure 4.

α3β1 is required for COX-2 mRNA expression and PGE2 secretion in breast cancer cells. (A-C) Parental MDA-MB-231 cells (p), MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (shRNA, ctrl), or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells (shRNA, α3) were cultured for 24 hours in serum-free medium. Cells were assayed by (A) RT-PCR for α3, COX-2, and GAPDH mRNAs, or (B) immunoblot for COX-2 or ERK as a loading control. (C) Equivalent proportions of conditioned media were assayed for secreted PGE2. Graph shows relative PGE2 levels normalized to that in MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells (ctrl); mean +/− S.E.M.; n=3 experiments; *p<0.002, two-tailed t-test.

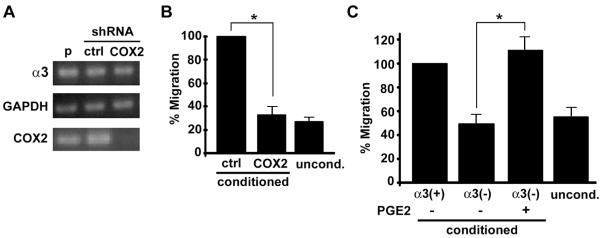

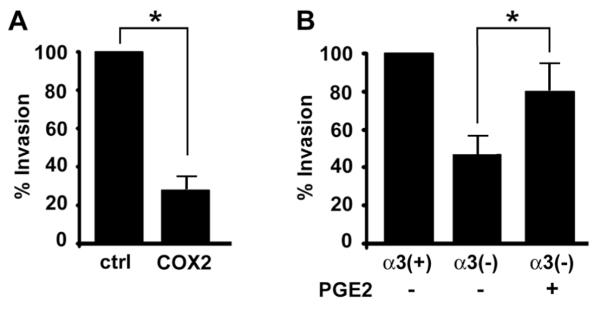

COX-2 contributes to tumor cell-to-endothelial cell crosstalk and tumor cell invasion

We next used shRNA to stably suppress COX2 mRNA in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5A). As expected, COX-2-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells showed reduced tumor growth (Supplementary Fig. S5), consistent with previous reports that COX-2 is necessary for tumorigenesis in both xenograft and genetic models [18, 20]. Interestingly, HUVECs showed no migration response to conditioned medium from COX-2-deficient MDA-MB-231 (Fig. 5B), implicating COX-2 in tumor cell-to-endothelial cell crosstalk. Tumor cell-derived PGE2 can have both autocrine effects and paracrine effects on endothelial cells [15]. Addition of PGE2 directly to endothelial cells did not stimulate migration under our conditions (data not shown), indicating that other factors are required. However, the HUVEC migratory response was restored in conditioned medium from α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells that had been pre-treated with PGE2 (Fig. 5C), indicating an autocrine mechanism and consistent with a previous report that PGE2 strongly induces pro-angiogenic factors in mammary tumor cells [15]. COX-2-deficient cells also showed reduced Matrigel invasion (Fig. 6A), and pre-treatment with PGE2 enhanced invasion of α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells (Fig. 6B). These findings indicate involvement of COX-2 in two tumor cell functions that we have shown to be regulated by α3β1: (1) ability to stimulate angiogenic endothelial cell function, and (2) invasion.

Figure 5.

COX-2 in breast cancer cells regulates induction of endothelial cell migration. (A) Parental MDA-MB-231 cells (p), or cells that stably express non-targeting (ctrl) or COX-2-targeting shRNA (COX2), were assayed by RT-PCR for COX-2, α3, or GAPDH mRNA. (B) Transwell assays were performed as in Fig. 2 to compare HUVEC migratory responses to conditioned medium from MDA-MB-231 cells that express control or COX-2-targeting shRNA; uncond, unconditioned medium. Graph shows HUVEC migration as percentage of that in response to medium from control MDA-MB-231 cells. (C) HUVEC migration was assayed in response to conditioned medium from MDA-MB-231/α3(+) or MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells that were either untreated or pre-treated for 24 hours with 1 ng/ml PGE2, as indicated. For (B) and (C), data are mean +/− S.E.M; n=3 experiments; *p<0.05, two-tailed t-test.

Figure 6.

COX-2 expression regulates breast cancer cell invasion. (A) Matrigel assays were performed as in Fig. 3 to compare invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells that express control (ctrl) or COX-2-targeting shRNA (COX2). Graph shows invasion as percentage of that in control cells; mean +/− S.E.M; n=3 experiments; *p<0.001, two-tailed t-test. (B) Invasion assays were performed in MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells, MDA-MB-231/α3(−) cells, or the latter cells pre-treated for 24 hours with 1ng/ml PGE2. Graph shows invasion as percentage of that in untreated MDA-MB-231/α3(+) cells; mean +/− S.E.M; n=4 experiments; *p<0.02, paired two-tailed t-test.

Discussion

Although many studies have demonstrated important roles for integrins in tumor growth and progression [2-4], roles for integrin α3β1 in carcinogenesis remain unclear. In the current study, we show that RNAi-mediated suppression of α3β1 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells leads to decreased tumorigenesis in vivo, and also inhibits both invasion and production of soluble factors that stimulate endothelial cell migration. In addition, real-time PCR arrays revealed that suppression of α3β1 in MDA-MB-231 cells causes dramatically reduced COX-2 gene expression (Supplementary Table 1), and RNAi experiments to suppress COX-2 implicated this gene in the regulation of α3β1-mediated tumor cell functions, including invasion and crosstalk to endothelial cells. Furthermore, treatment of α3β1-deficient cells with PGE2, an important effector of COX-2 signaling, restored both invasive potential and ability to stimulate endothelial cell migration. These findings identify a novel role for COX-2 as a downstream effector of α3β1 in breast cancer cells.

The cyclooxygenases COX-1 and COX-2 control metabolism of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins [29, 30]. While COX-1 is constitutively expressed in many tissues, COX-2 is induced by pro-inflammatory or mitogenic stimuli and is upregulated in several human cancers [30]. Clinical and preclinical studies strongly support pro-tumorigenic roles for COX-2 [17]. Indeed, the COX-2 gene is over-expressed in ~40% of invasive breast carcinomas and preinvasive ductal carcinomas in situ, and COX-2 promotes breast tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis [14-18, 29-34]. In addition, COX-2-dependent synthesis of PGE2 drives the angiogenic switch during breast cancer progression [15, 29, 33], and numerous pharmacological and genetic studies support a role for COX-2 in breast cancer [18-20]. Importantly, clinical and preclinical studies have supported the development of COX-2 inhibitors as chemo-preventative drugs [35, 36]. Therefore, our current results suggest the intriguing possibility that suppression of the COX-2 gene through inhibition of integrin α3β1 could produce similar protective effects.

Our finding that α3β1 was required in breast cancer cells for secretion of factors that stimulate endothelial cell migration is similar to a novel function that we recently described for this integrin during wound healing, where α3β1 was required in epidermal keratinocytes for secretion of factors that stimulate endothelial cell migration in vitro and wound angiogenesis in vivo [23]. These intriguing similarities suggest a generally important role for α3β1 in promoting communication from the epithelial/tumor cell compartment to the vasculature during normal and pathological tissue remodeling. Our current findings show that COX-2 may contribute to this effect in tumor cells, consistent with its known ability to induce expression of pro-angiogenic factors [15]. We have not yet identified α3β1/COX-2-dependent factor(s) that are produced by breast cancer cells to stimulate endothelial cells. However, we have explored the possibility that this effect is mediated by MMP-9, since this matrix metalloproteinase is pro-angiogenic [39], its induction by extracellular matrix has been linked to COX-2 signaling in some cells [40-42], and we have shown that α3β1 regulates MMP-9 expression in immortalized/transformed keratinocytes [11, 43]. Zymography experiments showed that MMP-9 secretion was reduced in α3β1-deficient MDA-MB-231 cells (data not shown), as also reported by another group [9]. However, in preliminary experiments we did not detect reduced MMP-9 in COX-2 knockdown cells, suggesting that MMP-9 production does not require COX-2 in these cells.

Interestingly, reduced COX-2 expression in α3-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells was not reversed by adenoviral expression of exogenous α3 (data not shown), indicating that this is a stable phenotype and that α3β1-mediated induction of COX-2 occurs through an indirect mechanism. On the other hand, restoring α3 expression in α3-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells did rescue invasion and crosstalk to endothelial cells (Figs. 2 and 3), indicating other α3β1-mediated pathways that can promote these functions independently of COX-2. Consistently, α3-silenced MDA-MB-231 cells also showed changes in other breast cancer-associated genes, including ~22-fold increase in expression of the CDH1/E-cadherin gene (Supplementary Table 1). This change is of potential interest, since down-regulation of E-cadherin is associated with malignancy, and forced expression of E-cadherin suppresses metastatic properties of MDA-MB-231 cells [38]. We are currently exploring contributions of this and other α3β1-dependent changes in gene expression to α3β1-mediated tumor cell functions.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to identify integrin-dependent maintenance of COX-2 gene expression in tumor cells. Another group showed previously that the noncollagenous domain of type IV collagen, α3(IV)NC1, inhibits hypoxia-induced COX-2 mRNA expression in endothelial cells by binding to integrin α3β1 on the endothelial cell surface [37]. It remains to be determined whether treatment with α3(IV)NC1 would similarly inhibit COX-2 expression in breast cancer cells. However, our current findings that α3β1 enhances, rather than inhibits, COX-2 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells indicate that roles for this integrin differ within distinct cellular compartments of the tumor microenvironment, and they highlight the likely importance of targeting α3β1 specifically on tumor cells to achieve an anti-angiogenic effect.

Integrin α3β1 interacts with tetraspanin CD151 on the cell surface [44, 45], and this complex has been shown to regulate cell motility and influence tumorigenic, invasive, and metastatic properties of breast and other carcinoma cells [25, 46-49] [50]. RNAi-mediated suppression of CD151 also reduces tumorigenicity of MDA-MB-231 cells [25], suggesting that it may be involved in at least some pro-tumorigenic functions of α3β1. Interestingly, CD151-integrin association was required for tumor cell growth response to factors secreted by endothelial cells [25]. Although CD151 on tumor cells also affected vascularization patterns in MDA-MB-231 xenografts, it did not appear to regulate secretion of factors that induce angiogenic morphology of endothelial cells [25]. These findings, together with our current results, suggest that α3β1 and CD151 can each regulate bidirectional communication between tumor cells and endothelial cells, although in some cases they may do so independently of one-another. Future studies will investigate the subset of α3β1-mediated tumor cell functions that require its binding to CD151.

In summary, we have identified a novel role for α3β1 on breast cancer cells in regulating communication with endothelial cells and promoting cell invasion, and we have identified COX-2 as a downstream effector of α3β1. Given the intense focus in recent years on clinical development of COX-2 inhibitors [17], our findings have important implications regarding potential value of α3β1 as a therapeutic target for breast cancer. The concept of targeting integrins in anti-cancer therapies is supported by preclinical and clinical development of antagonists of certain integrins (i.e. αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1); however, effects of targeting these integrins result largely from inhibiting their functions on endothelial cells (reviewed in [5]). Our current study suggests that targeting α3β1 on breast cancer cells may inhibit both tumor angiogenesis and invasion, in part through suppression of COX-2. Furthermore, since the ability of α3β1 to regulate cell adhesion and MMP expression can also influence carcinoma invasion/metastasis [8-11, 13], targeting α3β1 may have the combinatorial effect of inhibiting multiple tumor cell functions that promote malignant progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. John Lamar, Kevin Pumiglia, Peter Vincent, Paul Feustel, and Gang Liu for helpful discussions and technical assistance. In addition, we thank Drs. Martin Hemler and Joan Massague’ for gifts of reagents.

Grant Support: NIH R01CA129637 (C. M. DiPersio); Cancer Research UK C1322/A5705 (F. Berditchevski); NIH R01CA132977 (J. Zhao); European Commission FP7 programme grant ‘INFLA-CARE’, EC contract number 223151 (A. G. Eliopoulos). K. Mitchell was supported by a pre-doctoral training grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH-T32-HL-07194).

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interests are disclosed.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brakebusch C, Bouvard D, Stanchi F, Sakai T, Fassler R. Integrins in invasive growth. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:999–1006. doi: 10.1172/JCI15468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felding-Habermann B. Integrin adhesion receptors in tumor metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:203–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1022983000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mercurio AM, Bachelder RE, Chung J, et al. Integrin laminin receptors and breast carcinoma progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2001;6:299–309. doi: 10.1023/a:1011323608064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stupp R, Ruegg C. Integrin inhibitors reaching the clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1637–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alghisi GC, Ruegg C. Vascular integrins in tumor angiogenesis: mediators and therapeutic targets. Endothelium. 2006;13:113–35. doi: 10.1080/10623320600698037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreidberg JA. Functions of alpha3beta1 integrin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:548–53. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuji T. Physiological and pathological roles of alpha3beta1 integrin. J Membr Biol. 2004;200:115–32. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0696-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morini M, Mottolese M, Ferrari N, et al. The alpha 3 beta 1 integrin is associated with mammary carcinoma cell metastasis, invasion, and gelatinase B (MMP-9) activity. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:336–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, Fu W, Im JH, et al. Tumor cell alpha3beta1 integrin and vascular laminin-5 mediate pulmonary arrest and metastasis. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:935–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamar JM, Pumiglia KM, DiPersio CM. An immortalization-dependent switch in integrin function up-regulates MMP-9 to enhance tumor cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7371–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chia J, Kusuma N, Anderson R, et al. Evidence for a role of tumor-derived laminin-511 in the metastatic progression of breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2135–48. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marinkovich MP. Tumour microenvironment: laminin 332 in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:370–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boland GP, Butt IS, Prasad R, Knox WF, Bundred NJ. COX-2 expression is associated with an aggressive phenotype in ductal carcinoma in situ. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:423–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang SH, Liu CH, Conway R, et al. Role of prostaglandin E2-dependent angiogenic switch in cyclooxygenase 2-induced breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:591–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535911100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Half E, Tang XM, Gwyn K, Sahin A, Wathen K, Sinicrope FA. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human breast cancers and adjacent ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1676–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howe LR. Inflammation and breast cancer. Cyclooxygenase/prostaglandin signaling and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:210. doi: 10.1186/bcr1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stasinopoulos I, O’Brien DR, Wildes F, Glunde K, Bhujwalla ZM. Silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibits metastasis and delays tumor onset of poorly differentiated metastatic breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:435–42. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu CH, Chang SH, Narko K, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 is sufficient to induce tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18563–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howe LR, Chang SH, Tolle KC, et al. HER2/neu-induced mammary tumorigenesis and angiogenesis are reduced in cyclooxygenase-2 knockout mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10113–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yiu GK, Toker A. NFAT induces breast cancer cell invasion by promoting the induction of cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12210–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell K, Szekeres C, Milano V, et al. α3β1 integrin in epidermis promotes wound angiogenesis and keratinocyte-to-endothelial-cell crosstalk through the induction of MRP3. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1778–87. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baldwin G, Novitskaya V, Sadej R, et al. Tetraspanin CD151 regulates glycosylation of α3β1 integrin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35445–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadej R, Romanska H, Baldwin G, et al. CD151 regulates tumorigenesis by modulating the communication between tumor cells and endothelium. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:787–98. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inoue M, Itoh H, Ueda M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in human coronary atherosclerotic lesions: possible pathophysiological significance of VEGF in progression of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1998;98:2108–16. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.20.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiPersio CM, Shah S, Hynes RO. α3Aβ1 integrin localizes to focal contacts in response to diverse extracellular matrix proteins. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2321–36. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundstrom A, Holmbom J, Lindqvist C, Nordstrom T. The role of alpha2 beta1 and alpha3 beta1 integrin receptors in the initial anchoring of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells to cortical bone matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:735–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang MT, Honn KV, Nie D. Cyclooxygenases, prostanoids, and tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:525–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams CS, Mann M, DuBois RN. The role of cyclooxygenases in inflammation, cancer, and development. Oncogene. 1999;18:7908–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies GL. Cyclooxygenase-2 and chemoprevention of breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ristimaki A, Sivula A, Lundin J, et al. Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase-2 expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:632–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh-Ranger G, Salhab M, Mokbel K. The role of cyclooxygenase-2 in breast cancer: review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:189–98. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9641-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wulfing P, Diallo R, Muller C, et al. Analysis of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human breast cancer: high throughput tissue microarray analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:375–82. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0459-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dannenberg AJ, Altorki NK, Boyle JO, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase 2: a pharmacological target for the prevention of cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:544–51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00488-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howe LR, Subbaramaiah K, Brown AM, Dannenberg AJ. Cyclooxygenase-2: a target for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:97–114. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boosani CS, Mannam AP, Cosgrove D, et al. Regulation of COX-2 mediated signaling by alpha3 type IV noncollagenous domain in tumor angiogenesis. Blood. 2007;110:1168–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mbalaviele G, Dunstan CR, Sasaki A, Williams PJ, Mundy GR, Yoneda T. E-cadherin expression in human breast cancer cells suppresses the development of osteolytic bone metastases in an experimental metastasis model. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4063–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737–44. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan KM, Howe LR, Falcone DJ. Extracellular matrix-induced cyclooxygenase-2 regulates macrophage proteinase expression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22039–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Itatsu K, Sasaki M, Yamaguchi J, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 is involved in the up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in cholangiocarcinoma induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:829–41. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bansal K, Kapoor N, Narayana Y, Puzo G, Gilleron M, Balaji KN. PIM2 Induced COX-2 and MMP-9 expression in macrophages requires PI3K and Notch1 signaling. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iyer V, Pumiglia K, DiPersio CM. Alpha3beta1 integrin regulates MMP-9 mRNA stability in immortalized keratinocytes: a novel mechanism of integrin-mediated MMP gene expression. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1185–95. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yauch RL, Berditchevski F, Harler MB, Reichner J, Hemler ME. Highly stoichiometric, stable, and specific association of integrin alpha3beta1 with CD151 provides a major link to phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, and may regulate cell migration. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2751–65. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.10.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berditchevski F, Gilbert E, Griffiths MR, Fitter S, Ashman L, Jenner SJ. Analysis of the CD151-alpha3beta1 integrin and CD151-tetraspanin interactions by mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41165–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugiura T, Berditchevski F. Function of alpha3beta1-tetraspanin protein complexes in tumor cell invasion. Evidence for the role of the complexes in production of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1375–89. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winterwood NE, Varzavand A, Meland MN, Ashman LK, Stipp CS. A critical role for tetraspanin CD151 in alpha3beta1 and alpha6beta4 integrin-dependent tumor cell functions on laminin-5. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2707–21. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang XH, Richardson AL, Torres-Arzayus MI, et al. CD151 accelerates breast cancer by regulating alpha 6 integrin function, signaling, and molecular organization. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3204–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zijlstra A, Lewis J, Degryse B, Stuhlmann H, Quigley JP. The inhibition of tumor cell intravasation and subsequent metastasis via regulation of in vivo tumor cell motility by the tetraspanin CD151. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:221–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang XH, Flores LM, Li Q, et al. Disruption of laminin-integrin-CD151-focal adhesion kinase axis sensitizes breast cancer cells to ErbB2 antagonists. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2256–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.