Abstract

Genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) includes genotyping for apolipoprotein E, for late-onset AD, and three rare autosomal dominant, early-onset forms of AD associated with different genes (APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2). According to researchers, patents have not impeded research in the field, nor were patents an important consideration in the quest for the genetic risk factors. Athena Diagnostics holds exclusive licenses from Duke University for three “method” patents covering APOE genetic testing. Athena offers tests for APOE and genes associated with early onset, autosomal dominant AD. One of those presenilin genes is patented and exclusively licensed to Athena; the other presenilin gene was patented but the patent was allowed to lapse; and one (APP) is patented only as a research tool and patent claims do not cover diagnostic use. Direct-to-consumer testing is available for some AD-related genes, apparently without a license. Athena Diagnostics consolidated its position in the market for AD genetic testing by collecting exclusive rights to patents arising from university research. Duke University also used its licenses to Athena to enforce adherence to clinical guidelines, including elimination of the service from Smart Genetics, which was offering direct-to-consumer risk assessment based on APOE genotyping.

Keywords: Patents, Intellectual Property, Alzheimer Disease, Athena Diagnostics, genetic testing

INTRODUCTION

As the most common form of dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) currently afflicts over 5 million Americans, a number expected to increase to 16 million by 2050.1 Total estimated costs of healthcare for AD were $33 billion in 1998; rising to $61 billion by 2002.1 Because it strikes so many and costs so much, it is important to understand whether and how patenting and licensing practices might affect the millions of people who will be concerned about genetic risks associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease as currently classified has several forms. Two are relevant to genetic testing. A very small percentage of AD cases arise in family clusters with early onset. Familial early-onset AD (EOAD) is usually caused by an autosomal dominant mutation in one of three genes: PSEN1 (chromosome 14), PSEN2 (chromosome 1), or APP (chromosome 21). A person with one of these fully penetrant mutations will contract the disease if they live long enough, usually developing symptoms before age 60. These families are quite rare, but the 50% risk of each child of an affected member means these tests can be important for those at risk.

The vast majority of people who develop AD have the late-onset form (LOAD), which has only one clearly established and robust genetic risk factor known as APOE (the gene that encodes the protein apolipoprotein E). Those who inherit the ε4 allele from one parent have an elevated risk of developing AD, and those who inherit ε4 alleles from both parents have a markedly elevated risk (up to an odds ratio of 16 relative to the population average for Caucasian males, for example). Recent studies based on genome-wide association with markers suggest there may be other genetic risk factors, but the next most significant locus after APOE, on chromosome 12, is many, many orders of magnitude less predictive.2 The high-risk ε4 genotype is not necessary to predict or diagnose AD. While the APOE genetic test is used in a relatively small fraction of LOAD cases, the much larger number of late-onset AD cases means it is more frequently used than the genetic tests for PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP in high-risk families.

Patents relevant to genetic testing for all four genes have been granted in the United States. The patenting landscape is complex. The APOE gene itself is not patented, nor are mutations or polymorphisms, but testing to predict Alzheimer’s risk is the subject of three “methods” patents issued to Duke University and licensed exclusively to Athena Diagnostics. PSEN1 and PSEN2 gene sequences and their variants have been patented and exclusively licensed to Athena Diagnostics. APP is the subject of several patents for making animal models, but not of a sequence patent per se. Athena offers genetic testing for PSEN1, PSEN2, APP, and APOE. When this case study was first being prepared in summer 2007, testing for PSEN2 and APP was not listed on Athena’s website, and clinicians did not know of a CLIA-certified laboratory offering such testing, but starting February 2008, these tests were offered by Athena.

Direct-to-consumer APOE testing was available March-October 2008 through Smart Genetics. Smart Genetics ceased offering APOE risk assessment for Alzheimer’s disease to consumers in October 2008.3 Direct-to-consumer APOE testing remains advertised through Graceful Earth’s website, and APOE ε4 status is indirectly assessed by at least one of the “personal genomics” firms (see below).

BACKGROUND

AD accounts for 50% to 70% of all cases of dementia. Even without genetic factors, the lifetime risk of AD in the general population is estimated at 15%, with prevalence of the disease doubling every five years after the age of 65 so that nearly 40% of the population aged 85 and older has AD.4 The most common symptom is gradually worsening memory loss, especially short-term memory, learning, and new memory formation. As the disease advances, victims typically experience confusion and disorientation, impaired judgment, and difficulty speaking and writing. Eventually AD patients lose their ability to do simple everyday tasks like bathing, dressing, and eating. Ultimately those with AD reach a point where they no longer recognize family and friends, lose the ability to communicate, and become bed-bound.1 AD is incurable and fatal, though the average patient can expect to live 8 to 10 years beyond the initial appearance of symptoms.5 Some live far longer.

The neuropathology of AD consists of plaques of beta-amyloid protein deposited in the brain and neurofibrillary tangles of another protein called tau inside nerve cells.6, 7 Scientists and clinicians debate whether the plaques and tangles are the cause or the result of cell death. Most researchers now ascribe to the “amyloid cascade” hypothesis, which postulates that the accumulation of A-beta amyloid is toxic to nerve cells. Elucidating the pathogenic pathway and developing new leads for treatment are extremely active areas of research. Other abnormalities in the brain of a person with AD can include inflammation and oxidative stress.6 While correct diagnosis of AD has improved greatly since its discovery, approaching or exceeding 90% in academic centers, 8 the gold standard for AD is autopsy confirmation, when the brain can be examined for the telltale plaques and tangles, combined with a clinical history of dementia.7

Early-onset AD

EOAD accounts for fewer than 3% of all AD cases, which amounts to less than 50,000 people in the U.S.7, 9 Some inherited cases are missed. Early-onset cases lacking family history may truly lack inherited risk, or the family history may have missed past cases for one of many reasons. Current classifications have only been in place for the past three decades in a disease with onset late in life, and with few autopsies performed to give definitive diagnosis. Until recent decades, premature deaths (before usual AD onset) were common, so those dying might have developed dementia had they lived long enough. Or affected cases may have died with dementia but it was not reported as the cause of death, nor recorded in family records. Moreover, expectations of “senility” were common, so that those developing symptoms often were not understood to have disease-related dementia. Family history of past cases is thus even more uncertain than for most other conditions.

Familial EOAD (or EOFAD) is usually caused by autosomal dominant mutations in the APP, PSEN1 or PSEN2 genes, although there are additional families with autosomal dominant inheritance pattern in which no mutation has yet been identified. 7 In families with autosomal dominant EOAD, each child of an affected parent has a 50% chance of also having the mutant gene, and therefore developing EOAD if they live long enough. Upon genetic testing, sometimes a new EOAD family reveals a mutation in one of the three known genes; other times no mutation is found to explain the inheritance pattern and testing is inconclusive.7 In one of the larger studies of EOAD families to date, mutations in the PSEN1 gene accounted for 66% of EOAD families, mutations in APP for another 16%, and 18% were unknown.10 (Note these numbers are for familial cases, not sporadic ones. EOAD is not always inherited and genetic testing has a very low yield in nonfamilial cases.)

APP

The amyloid precursor protein (APP) was discovered in the 1980s.11, 12 A mutation in the gene encoding this protein was the first to be linked with AD, in 1991.13, 14 The APP gene resides on chromosome 21 and contains at least 36 mutations, of which 30 are believed pathogenic.14 However, this is an extremely rare cause of AD, affecting only approximately 30 known families worldwide. Age of onset ranges from 39 to 67 years. APP-related disease can be influenced by the individual’s APOE genotype, the gene that plays a role in late-onset AD.15 Those with an APP mutation and the ε4 high-risk allele of APOE generally have an even earlier age of onset than relatives with APOE- ε2 or ε3.9

PSEN1

Presenilin-1 mutations are the most common among the three known EOAD-associated genes. PSEN1 mutations account for the majority of EOAD cases where onset is before age 50. Discovered in 1992, PSEN1 is located on chromosome 14 and harbors over 180 different mutations, of which 173 are believed pathogenic.14 Victims of such mutations generally have more severe clinical syndromes, such as earlier onset of seizures and language disturbance, than those with mutations in APP or PSEN2 genes.4 AD associated with PSEN1 has onset between ages 28 and 64, with an average age of onset of 45 years.15

PSEN2

The PSEN2 gene that encodes the presenilin-2 protein was discovered quickly after PSEN1 because of its similar DNA sequence. It is known as “the Volga German gene” since mutations in PSEN2 were isolated on chromosome 1 in a group of apparently related German families that settled in the Volga River region of Russia before coming to the U.S., where their mutation was subsequently discovered.16 Mutations in PSEN2 are extremely rare, having only been identified in one familial group. The average age of onset is 52 years (with a wide range from 40 to 75 years) with APOE ε4 again associated with somewhat earlier onset.7, 16 Twenty-two mutations in PSEN2 have been reported, fourteen of which are deemed pathogenic.14

Late-onset AD

LOAD is associated with both genetic and other risk factors. While the primary risk factors are age and family history, other factors such as susceptibility genes, exposure to toxins, previous head injury, female gender, and low level of education may also play a part.5

APOE

Apolipoprotein E is a cholesterol transport protein (generally written APOE for the gene, and ApoE or apoE for the protein). ApoE protein is encoded by a gene on chromosome 19. There are three common alleles, ε2, ε3, and ε4. In the general population, APOE ε4/4 represents approximately 2%; 3/4 represents 21%; 3/3 represents 60%; 2/3 represents 11%; 2/4 represents 5%; and 2/2 represents less than 0.5%.17

APOE ε4 is associated with an increased risk of AD, while APOE ε2 acts as a mildly protective factor. Persons with APOE ε4/ ε4 have increased risk—more than sixteen-fold higher among Caucasian males at peak relative risk—and they have earlier age of onset than individuals with only one ε4 (three-fold higher risk in Caucasian males). Individuals with only one ε4 have a higher risk and earlier onset, in turn, than those with no ε4 alleles. (There are some variants among the ε3 alleles themselves also, although risk curves for sub-subgroups have not been developed for clinical use in detail.) The median onset among those homozygous for ε4 (ε4 /ε4) is before age 70, while among those who develop AD with the ε2/ε3 genotype, the median age of onset is over 90. 7, 17

Ashford estimates that approximately 50% of the risk of AD is attributable to APOE genotype.18 Yet APOE is neither necessary nor sufficient to predict or diagnose AD.7 “Although Alzheimer’s disease occurs in many patients who carry the [APOE ε4] allele, a significant number of carriers do not get the disease. In addition, only about half of patients with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease have the [APOE ε4] allele” (p. 120).15 By age 90, it is rare to identify ε4/ ε4 individuals without onset of dementia. Relative odds of developing AD based on the three alleles differ according to sex and race.7, 19

Other Possible Genetic Influences

Because AD affects so many people, research in the field is abundant, to the point that in 2004, Bertram and Tanzi reported “more than 10 genes are reported to show either positive or negative evidence for disease association per month” (p. R135).8 In 90 studies reporting 127 association findings in 2003, only 3 associations between candidate genes and AD were confirmed by three or more independent studies. These loci occurred at chromosomal locations 6p21, 10q24, and 11q23.8 The recent turn to genome-wide association methods has turned up some signals, but all are far weaker than the APOE genotype.2 Nothing conclusive has been determined, however, so APOE remains the only established clinically significant susceptibility gene for late-onset AD.

The vast majority of contributions to the Human Genome Mutation Database and Alzheimer and FTD Mutation Database, which catalog AD mutation research, come from academic research centers, and not from Athena Diagnostics, in contrast to the heavy contribution of Myriad Genetics to the analogous mutation database for BRCA1/2 mutations. Athena Diagnostics presumably tracks utilization of its various genetic tests as part of its royalty agreements, but these data are not publicly reported. The system of studying AD thus relies primarily on clinicians and academic researchers rather than family studies conducted or carried out by Athena.

PATENTS AND LICENSING

Athena Diagnostics has exclusive licenses to three APOE patents, all of which were granted to Duke University: U.S. 5508167, U.S. 5716828, and U.S. 6027896. The first and third patents have methods claims and the second claims a testing kit. The methods claims are based on APOE genotype (both direct and indirect determinations) and “observation” of AD risk. These may be claims of the type that the October 2008 decision of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) In re Bilski cast into doubt. 20 The CAFC states, “A claimed process is surely patentable under [Sec.] 101 if (1): it is tied to a particular machine or apparatus, or (2) it transforms a particular article into a different state or thing” (p. 954).20 Duke’s patents have not been challenged under this standard.

According to Dr. Allen Roses, first inventor on the patents, the patents were sought because of well known chicanery in publication and reviewing in academic AD research at the time. The gene hunts for PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP were characterized by competitive races and nasty controversies, including conflicting claims of scientific priority (Personal communication with Dr. Allen Roses). Allegedly, researchers delayed other scholars’ papers in review, disputed data and material sharing agreements to the extent that research was delayed, used other researchers’ family pedigrees and clinical materials without permission, and withheld permission for the reuse of data and materials. These stories are recounted, in somewhat muted form, in Hannah’s Heirs and Decoding Darkness.16,21 Dr. Roses noted other instances of dubious conduct. The first APP717 mutation reported in Nature in 1991 used two families, the larger of which was provided by the Roses Laboratory, but the patenting of the discovery and the submitted publication did not acknowledge this; similarly, the Roses Laboratory provided approximately one-fourth of the patients for discovery of the PSEN1 locus, but was excluded from authorship of the publication (Personal communication with Dr. Allen Roses).

Dr. Roses’ solution to such problems for research on the APOE gene was to file a patent application for APOE screening to establish a documentary record. The Duke APOE patents were exclusively licensed to ensure that the genotyping was only done “for physicians who confirmed a finding of dementia… [and] we felt that we could monitor the activity better with one license” (Personal communication from Dr. Allen Roses). Because APOE is neither necessary nor sufficient to diagnose AD, Dr. Roses indicated the intention was to use the patent license from Duke to ensure APOE testing would not be used as a presymptomatic screening test; it could only be used for patients already clinically diagnosed with dementia.

We have not been able to confirm these licensing terms, although we submitted questions to both Duke’s Office of Licensing and Ventures and to Athena Diagnostics (See Appendix 5 for responses from Duke’s Office of Licensing and Ventures). Athena initially sublicensed the APOE patents to Smart Genetics, which began offering direct-to-consumer genetic risk assessment for AD in March 2008. The test was widely advertised, including a March “survey” of consumers’ willingness to undergo genetic testing through Parade Magazine, the most widely circulated publication in the nation.22 Allen Roses was asked to become a consultant of Smart Genetics, refused, and notified Duke University that it was his understanding the license for the patents on which he is first inventor permitted APOE testing only for those with a physician’s certification of a diagnosis of dementia. Smart Genetics ceased operations in October 2008.23, 24 An October 2008 report in Nature corroborates the cessation of Smart Genetics risk-assessment testing, and attributes it to licensing terms between Duke and Athena, although the licensing terms between Duke and Athena are not public.3 “’The test was never intended to be used for wholesale screening of non-cognitively impaired individuals,’ adds Alan Herosian, director of corporate alliances for Duke University. He says he has contacted Athena many times in recent months to press this point. Michael Henry, Athena’s vice-president of business development, wouldn’t comment on whether the company agreed with this interpretation of its licence. But Smart Genetics is no longer taking new orders for Alzheimer’s Mirror” (p. 1155).3

Athena Diagnostics has sent several cease-and-desist letters to laboratories offering APOE testing, including one to the University of Pennsylvania to stop APOE testing.25

Athena also licensed two patents for the presenilin genes. U.S. 5840540 covers the PSEN2 gene and mutations and U.S. 6194153 includes methods claims for PSEN1. These are two patents in a series of five on PSEN1 and PSEN2, four of which were assigned to the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto) and the University of Toronto. They include U.S. 5986054 (covering the proteins of PSEN1), U.S. 6194153 (which Athena licensed), U.S. 6117978 (covering the proteins of PSEN2), and U.S. 6485911 (covering the methods of PSEN2). The remaining patent is U.S. 5840540, which Athena also licensed. It was assigned only to the Hospital for Sick Children. What is noteworthy here is that Athena only licensed two of the patents and that the patents are two different types of patents. Athena exclusively licensed the gene (sequence) patent for PSEN2 and the methods patent for PSEN1. The Toronto group, under lead inventor-scientist Peter St. George-Hyslop, has another patent that appears to cover the PSEN1 sequence, called the Alzheimer’s Related Membrane Protein in their patent (U.S. 6531586), but this does not appear on Athena’s list of exclusively licensed patents.26

Another patent, U.S. 6248555, was assigned to the General Hospital Corporation (Massachusetts General Hospital’s holding trust for patents) in Boston. This patent covers a mutant PSEN1 gene. Athena did not license it. Instead, another pharmaceutical licensing partner originally paid for its prosecution. When the licensing partner’s interest terminated, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) abandoned the patent, allowing it to enter the public domain (Personal communication with Dr. Colm Lawler, Senior Licensing Associate, Massachusetts General Hospital). MGH did so because at that point, the patent had less than half its life left and thus had very limited licensing potential and no immediate licensee options. MGH chose to conserve their patent resources and concentrate efforts on newer technologies.

Finally, a search of patents in the Delphion patent database by Dr. Robert Cook-Deegan found 355 US patents with claims mentioning an Alzheimer’s-specific term (Unpublished data from April 13, 2008). The search included patents granted with “presenilin or PSEN1 or PSEN2 or Alzheimer or ‘amyloid precursor’” in the claims. That search returned 355 granted US patents. The same text terms returned 5,172 patents and applications when the search was broadened to all fields, all jurisdictions in the Delphion database, and to both patents and applications. Many of these are clearly for research methods, transgenic animal models, and other purposes, and do not bear directly on genetic testing. A few, however, are of clear interest. Perlegen, for example, has a patent application for “Genetic Basis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Diagnosis and Treatment Thereof” that claims a collection of polymorphic sites (US 2006/0228728 A1/WO06083854A2). Its initial claim is for an AD genotype profile, which includes APOE and APP along with many other loci associated with AD risk. Even though the patent application may not be granted, it indicates that multiplex testing for AD is being commercially pursued and is the subject of patent applications.

International Patent Landscape

For APOE, a patent application assigned to Duke University was filed with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), WO/1994/009155: Methods of Detecting Alzheimer’s Disease. This application lists over 60 countries, but appears to have lapsed, been abandoned or rejected in most nations. There are patents in New Zealand, Canada, Germany, and UK. The US patents claim increased risk assessment in individuals, while the WIPO application claims “a method of diagnosing or prognosing Alzheimer's disease in a subject, wherein the presence of an apolipoprotein E type 4 (ApoE4) isoform indicates said subject is afflicted with Alzheimer's disease or at risk of developing Alzheimer's disease” (WIPO Patent WO/1994/009155, claim 1). The Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) issued patent number CA 2142300 in August 2005, 12 years after the application was filed.

Three patent applications for the presenilin genes were filed with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO): WO/1996/034099, WO/1997/027296, and WO/1998/001549. The first two were assigned to both the Hospital for Sick Children (HSC) and the University of Toronto, while the last patent was assigned only to the University. Four patents were granted in Canada. The first, CA 2200794, was assigned only to the University but the remaining three – CA 2219214, CA 2244412, CA 2259618 – were assigned to both HSC and the University of Toronto.

GENETIC TESTING

In the United States, AD testing is provided almost exclusively by Athena Diagnostics, which tests for LOAD using APOE, as well as EOAD using PSEN1, PSEN2 and APP genes. Athena has offered PSEN1 testing based on sequence analysis since 1997. The PSEN1 genotype test is priced at $1,675 (Personal communication with Athena Diagnostics, June 19, 2007). Prices for APP and PSEN2 are not public, and Athena Diagnostics declined to share prices with author Christopher Heaney as of May 2008 (Personal communication with Athena Diagnostics).

Using targeted mutation analysis, Athena offers APOE testing for $475. The Duke license to Athena gives worldwide exclusive rights for the Alzheimer’s ApoE patents (Personal communication with Rose Ritts, Director, Office of Licensing and Ventures, Duke University). Between June 2006 and June 2007, the Saint Louis University Health Science Center has offered APOE testing for cardiovascular purposes for $365. As of June 2007, some parties expressed interest, but none pursued testing (Personal communication with St. Louis University Health Science Center). Because the indication is for cardiovascular risks and not AD, this use does not infringe Athena’s patents (recall that Duke could not patent the DNA sequence, only the association with AD). Genotyping for cardiovascular risk thus does not infringe the Duke patents licensed to Athena Diagnostics. Several knowledgeable clinicians indicated in interviews and emails that APOE genotyping can be obtained through laboratories other than Athena, even when it is being used to assess AD risk.

In Canada, McGill University Health Center and Sunnybrook Molecular Genetics Laboratory both offer APOE testing for AD. As of June and 2007 and November 2008, respectively, McGill charges $100 (US dollars) and Sunnybrook $120 (Canadian dollars) (Personal communications with McGill University Health Center and Sunnybrook Molecular Genetics Laboratory). McGill has offered the test since 1993 by physician referral only, as the individual needs to exhibit realistic pre-test probability of having the disease. Sunnybrook also only offers testing for individuals with documented cases of AD.

Smart Genetics announced on February 7, 2008, that it entered an agreement with Athena Diagnostics to offer direct-to-consumer genetic testing for APOE.27 Part of the service, called “Alzheimer’s Mirror,” included educational materials, a saliva sampling kit, a post-test phone session with a genetic counselor, and ongoing support for managing test results.28 Initially priced at $399 and later dropped to $249, the test incorporated data on ethnicity, gender, family history, and APOE genotype to assess an individual’s AD risk. The testing was performed at a CLIA-certified laboratory. While not claiming to predict with certainty whether or not one would develop AD, it was the only direct-to-consumer AD genetic test that included genetic counseling and further support for users. As of October 2008, the Alzheimer’s Mirror website was still open, but the company apparently ceased operations early that month, and the website was unavailable by January 2009.23, 24

For $280, Graceful Earth, Inc., an online health alternatives website, promises “a genetic test…to accurately evaluate your risk for Alzheimer’s Disease and Atherosclerosis.”29 This is a direct-to-consumer test that does not require physician approval. Consumers send Graceful Earth a saliva sample. Genetic counseling is not listed as a service on the company’s website. There is no indication of a license from Duke or a sublicense from Athena Diagnostics on the Graceful Earth website.

INSURANCE COVERAGE AND REIMBURSEMENT

In general, private insurers deem genetic testing as medically necessary when the following conditions are met: (1) family history shows a high likelihood of inherited AD risk; (2) sensitivity of the test is known; (3) the results have direct impact on treatment for the patient; (4) the diagnosis would be unclear without testing; and (5) in some cases, if pre- and post-test counseling is provided (p. 81).30 In the case of AD, the largest roadblocks to insurance coverage occur with the issues of direct impact on treatment (since AD is incurable). For late-onset AD (LOAD), APOE genotyping has an unclear value for diagnosis. Insurance coverage would presumably increase if APOE genotyping became important in deciding among drug or other treatment choices. The cost of genotyping would then be offset by avoiding the use of drugs or treatments that would not benefit people with particular genotypes. Several developments in Alzheimer’s drug development have indicated that there is a possibility of using APOE status as a pharmacogenomic test.31–33

While approximately a dozen insurers have policies on testing for genetic markers of familial AD, none of the policies formally and explicitly covers the test.30 BlueCross/BlueShield considers genetic testing to be investigational. Aetna also does not distinguish between EOAD and LOAD genetic testing. It concludes that all genetic testing for AD is experimental and investigational because the tests have not been shown to improve clinical outcomes of AD.34 In July 2007 Kaiser Permanente stated that it would cover genetic testing if a doctor deemed it medically necessary (Personal communication with Kaiser Permanente). As of November 2009, the company website says, “Most experts do not consider ApoE-4 testing a necessary or useful part of evaluating a person with suspected Alzheimer's disease.”35 CIGNA HealthCare currently does not cover APOE genotyping because it is considered experimental, investigational, or unproven.36 Alzheimer’s Mirror was not covered by insurance and, according to Smart Genetics, was priced for out-of-pocket payment.

In summary, testing for the rare early onset familial forms is sufficiently rare that it appears to be usually handled case by case; testing for APOE has not apparently become a standard of care with regular coverage and reimbursement under health plans. If APOE genotyping predicted response to drugs or other treatments, then its use might substantially increase, it would become incorporated into clinical standards, and coverage and reimbursement would become routine.

CURRENT GENETIC TESTING GUIDELINES

EOAD

A 1998 consensus statement, based on work from Stanford University, states, “At this time, genetic testing for AD is not appropriate for most people. Predictive or diagnostic genetic testing for people at high risk for carrying a highly penetrant mutation is an option that should be discussed, and that could reasonably be accepted or declined” (p. 6).37

LOAD

Testing is much more controversial for LOAD because of its inconclusive nature. Originally, Athena marketed the APOE testing as a predictor of AD but then backed away from it when several professional societies judged such testing as inappropriate. All scientific and governing bodies that have reviewed the matter advise against APOE genotyping as a predictive or screening test, especially for asymptomatic individuals.4 These groups include the American College of Medical Genetics/American Society of Human Genetics Working Group, the United Kingdom Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium, the Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee of Alzheimer’s Disease International, the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association.4, 38–42 A 2008 literature review stated, “There is general agreement that APOE testing has limited value [when] used for predictive testing for AD in asymptomatic persons” (p. 235).7

Although APOE genotyping can provide an increase in diagnostic confidence, diagnostic accuracy with current methods can already exceed 90%. Therefore, APOE is used as an adjunct diagnostic test for patients already presenting with symptoms of dementia. One study of LOAD diagnosis pooled pathological confirmation data from more than 2,500 patients from 26 Alzheimer’s research centers and concluded that “APOE genotyping does not provide sufficient sensitivity or specificity to be used alone as a diagnostic test, but when used in combination with clinical criteria it improves the specificity of diagnosis” to greater than 97% (p. 506).43 This study is a decade old and is still one of the largest and most elaborate studies to date.

A series of studies of disclosing APOE genotype to relatives of those with AD has been conducted in a multi-center clinical research consortium based at Boston University (BU). The Risk EValuation and Education for ALzheimer’s disease (REVEAL) study began in 2000 at BU, Case Western Reserve University, and Cornell University as a randomized trial of disclosing genotype and risk versus standard counseling and risk evaluation without genotype disclosure. (Several members of the original REVEAL team advised Smart Genetics. Robert Green, PI of the overall REVEAL study, is an unpaid consultant for several “personal genomics” firms and also for Smart Genetics.) The major paper reporting results from REVEAL I has been accepted for publication at the New England Journal of Medicine, but is not yet available. REVEAL II expanded to include Howard University, and oversampled African Americans who also received counseling based on ethnicity-specific risk curves. The protocol for disclosure was abbreviated from REVEAL I. REVEAL III is ongoing, with the addition of University of Michigan (replacing Cornell/Weill Medical College) and a further streamlining of protocol and the inclusion of cardiovascular risk assessment. REVEAL did not study diagnostic use of APOE testing, but rather disclosure of risk information to relatives of those affected with AD. It did, however, extensively use APOE genotyping. Athena Diagnostics performed the tests for the REVEAL trials at a deep discount. REVEAL is the largest clinical study of APOE genotyping, and as its results are reported, they will likely influence clinical use.

NON-GENETIC SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS OPTIONS

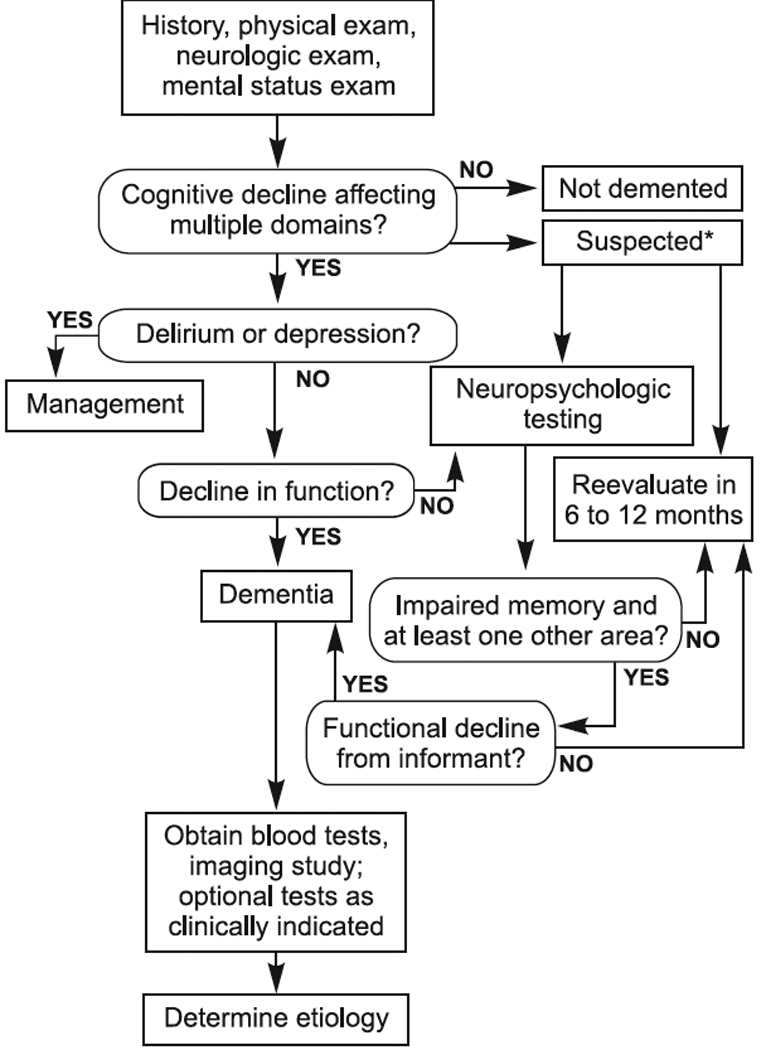

Since AD can appear in many ways, it is important that individuals, friends, family members, and family physicians be watchful for changes in an individual’s symptoms. A symptom checklist is provided in Appendix 1. Appendix 2 contains criteria for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s type dementia. Appendix 3 contains an algorithm for dementia evaluation and diagnosis.

Clinical recognition of progressive memory decline is usually a first step in diagnosing dementia. A physical examination can help determine the specific cause of dementia, for example, those caused by vascular disease or Lewy body disease (although these often occur in combination with AD).44 Physical examination should include evaluation of aphasia (speech), apraxia (motor memory), agnosia (sensory recognition), and executive functioning (complex behavior sequencing). Laboratory tests may be used to rule out other disorders like hypothyroidism that can cause symptoms of dementia.44

EOAD

While not diagnostic, analysis of cerebrospinal fluid for the 42 amino acid form of β-amyloid may be suggestive of early AD.44 (Tau levels are also measured. This is relevant to all AD, not just early onset.)

ROLE OF GENETIC TESTING

As noted above, with the exception of EOAD in descendants of affected individuals in high-risk, early-onset families, genetic testing for AD is not recommended at this time. Even for the small percentage of cases of EOAD, detection does not lead to reversal of the disease since there is no known cure for any form of AD. However, diagnosis can aid in increasing a patient’s quality of life and facilitating planning for life care and financial needs. In addition, a positive genetic test can end the quest for a specific diagnosis. There is some indication that APOE ε4 is an indicator of poor response, especially in women, to acetylcholinesterase treatments, which has obvious implications for drug prescriptions.45

Life Management

Diagnosis, especially in the earlier stages of AD, allows patients to make informed decisions about long-term finances, nursing care options, living wills, etc. Non-medical treatments to improve quality of life such as support groups and increased exposure to music and art can help substantially on the individual level.

“Personalized genomics” and AD testing

Patents and intellectual property concerns could influence the direct-to-consumer “personal genomics” services that are springing up, although we have limited specific information about this. Two examples of how patents might emerge as important can help illustrate the possible future complexities: (1) patents on multiplex genetic testing (or “genomic profiling”), and (2) enforcement of existing patents against multiplex testing. The Perlegen patent application noted above (US 2006/0228728 A1/WO060838354A2) indicates that multi-locus genetic testing is being contemplated commercially. It is also possible that existing patents on genes, mutations, and methods pertinent to genetic tests of many DNA variants associated with AD could be a future legal battleground, if new uses are found to infringe such patents (or if those wanting to use new methods choose to challenge the validity of claims in existing patents).

It is clear that some risk information about Alzheimer’s disease is being disclosed to at least some of those who use “personal genomics” testing services. The April 14, 2008, feature story in the Los Angeles Times opens with the author’s receipt of APOE risk information about AD from Navigenics in the service that became available that week. 46 The test was based on a DNA base change linked to the APOE ε4 allele. The wording of the relevant claims of the Duke patents is highly convoluted and its interpretation would require legal expertise and might entail disagreement that would be settled definitively only if litigated to completion. We have asked both Duke and Athena about sublicenses for risk assessment consumer testing but have received no reply.

Navigenics has a page on its website with its gene patent policy, stating its willingness to license patents, with a formula for specifying royalties.47 A crucial paragraph in that policy explains:

“Because our service uses multiple SNPs to assess your genetic risk for a variety of conditions, it requires a new kind of licensing approach for gene patents. For example, if we obtain licenses from third parties to 10 patents, each covering the use of one SNP included in our service, and each subject to a royalty of between 1 percent and 5 percent of our net sales of the service, we would be required to pay between 10 percent and 50 percent of our net sales revenue — just for gene patent licenses! Now consider that the whole genome scanning platform currently utilized in the Navigenics Health Compass service analyzes approximately 900,000 SNPs, and that for certain health conditions included in our service we look at more than 10 SNPs. Also note that this example does not include any upfront or milestone fees or annual minimum royalties, which make the traditional gene patent licensing approach even more untenable for this type of service.”

Their royalty model is specified as: “We have developed, with input from third parties, a universal royalty model for licensing gene patents for services such as the Navigenics Health Compass. In this model, royalties payable to a hypothetical Party X for a license to patents covering one or more SNPs used by the service to assess risk for hypothetical Condition Y would be calculated as follows: 5% of Net sales×((# of licensed SNPs for Condition Y/total # of SNPs for Condition Y)/# Conditions in service).”

If there were a license, then presumably Athena and Duke would receive a royalty stream. If there were no such license, then the Duke patents might be enforced against the testing firms, which would either lead to settlement or litigation. Athena might choose not to enforce its patents against personalized genomics firms, however, if it judged that personal genomics services would drive business to their AD testing service for confirmation in a CLIA-certified laboratory. It is also unclear whether multiplex testing along the lines implied by the Perlegen patent application would require a license for the AD-associated genes and mutations covered by patents.

One interesting sidelight on the personal genomics business models is AD risk assessment by deCODEme. The Duke patent was licensed to Athena with worldwide exclusive rights, but Duke did not secure patent rights in Iceland. DeCODE is therefore not infringing the patent by carrying out the tests there, and courts would have to decide if importation of information (test results) back to the United States would constitute infringement of patent claims.

LESSONS LEARNED

EOAD is important in those families at risk but such families are rare, and thus the market for such testing is small. During the period when it was not clear whether testing for PSEN2 and APP were even being offered, families faced an access problem, but not one specifically attributable to patent status. Rather, the limitation was absence of a CLIA-approved testing service for genetic testing. We are not aware of enforcement actions for EOAD testing.

The most recent developments in late-onset AD genetic testing are its use in those with mild cognitive impairment and the new availability of direct-to-consumer testing. APOE testing has been considered for use in clinical trials that involve those with mild cognitive impairment, as a way to identify those most at risk of progressing to dementia. APOE genotype is also available direct-to-consumer through some genetic testing services and, as noted, using indirect markers of APOE status, through some “personal genomics” services.

Basic Research

On one hand, an argument can be made that patents were part of the mix of motivations that spurred innovation in Alzheimer’s research. Two books, Daniel Pollen’s Hannah’s Heirs and Rudolph E. Tanzi’s Decoding Darkness, document the hyper-competitive races to trace the genetic origins of Alzheimer’s Disease.16, 21 Some of the major competitors in these races found their way to the patent office with claims covering EOAD, transgenic models of AD, and other inventions related to the research. Inventors on various patents include Dr. Peter St. George-Hyslop of the Toronto group, Dr. Tanzi of Massachusetts General, Drs. Thomas Bird and Jerry Schellenberg of the University of Washington; Dr. Christine van Broekhoven (then of Antwerp; US 5525714 claiming an APP mutation), Dr. John Hardy (then of Imperial College, London; US 5877015, another APP mutation), and Dr. Allen Roses of Duke University concentrated on APOE for LOAD, as well as co-inventors on their respective teams. From various accounts, there was intense animosity among the different research teams, and competition to discover and publish findings motivated the speed of AD research (Personal communications with Dr. Allen Roses, Dr. Tom Bird, Dr. Rudolph Tanzi, David Galas, formerly of Darwin Molecular when it collaborated with Drs. Schellenberg and Bird to sequence EOAD-associated genes and now at Battelle Memorial Institute). Both publications and patents were pursued by the various competing laboratories. At least in the initial period of discovery, the patenting landscape encouraged research, or at least did not dramatically hinder it. Dr. Tanzi expressed concern about Athena’s patent control of the A-beta protein patents in connection with AD A (Personal communication with Dr. Rudolph Tanzi).

Most of the researchers we interviewed expressed ambivalence about patenting, and none attributed the intensity of the races to patent priority. Rather, they stated that the races were driven by wanting priority of scientific discovery, prestige, scientific credit, and the ability to secure funding for additional research based on scientific achievement. If patents added “the fuel of interest to the fire of genius,” in Abraham Lincoln’s famous phrase, it was here at best a tiny pile of kindling at the outer margin of a large conflagration.

Having not found patents to be a significant impediment to research on AD, are patent benefits any clearer? Here again, it is difficult to argue that patents added much fuel to a fire that was already raging to hypercompetition. Indeed, Dr. Roses corrected us in the interview when we asked if one reason he sought a patent was to verify priority of his discovery associating APOE ε4 with elevated risk of AD. He said it was not a reason, but it was the only reason he sought a patent (Personal communication with Dr. Allen Roses). According to those who were in the race, research would not have slowed without a patent incentive.

Patents did, however, provide a mechanism for academic research institutions to convey rights to Athena Diagnostics, which aggregated patent rights from disparate academic groups to become the main testing service for AD in the United States. Athena Diagnostics’ business interests cover the United States, Canada and Japan, and it also does some testing for Europe. In several jurisdictions including the United States, Athena has collected rights to genetic tests for many neurological conditions, and it has a sales force that keys to neurologists and other brain disease specialists. Where Athena enforced its exclusively licensed patents against other diagnostic services, it is clear that alternative providers were reduced in number.48 It is impossible to judge, however, whether this has had an impact on clinical access, or even whether it has affected price (with the exception of APOE testing in Canada, which is listed for considerably less than Athena’s price from two providers).

The role of patents in AD testing is thus clear in the sense that it has enabled Athena Diagnostics to consolidate the testing market in the United States. Whether this is optimal for the US health system as a whole is less clear.

Development and Commercialization

Appendix 4 shows a pricing chart of all available AD testing in the U.S. and Canada. With the exception of preimplantation genetic diagnosis, Athena Diagnostics has been the only company offering APOE and PSEN1 screening since it became available, except the 8-month period when Smart Genetics operated with a sublicense. We found no indication that Graceful Earth has a license for APOE genotyping to assess AD risk, and ambiguity about APOE testing for cardiovascular disease (which would not infringe the patents) may enable some AD genetic testing for APOE without a license. Cardiovascular testing would be completely legitimate, while interpreting AD risk assessment or diagnosis from APOE genotyping would be difficult to detect. Within the past year, the Saint Louis center has offered APOE testing for cardiovascular purposes (Personal communication with St. Louis University Health Science Center).

It remains to be seen if Duke or Athena will enforce the Duke patents against Graceful Earth or personal genomics firms. Unlike academic centers to which Athena has previously sent cease-and-desist letters, Graceful Earth is not transparent about its process of AD testing, makes no mention of CLIA laboratory certification, and alongside its APOE screening also offers pet hair analysis and herbal supplements.29 It did not receive a letter from the California Department of Health regarding regulation of direct-to-consumer testing, and the authors did not know if the company received a letter from New York’s Department of Health. Graceful Earth is not therefore a major clinical service provider, and its direct-to-consumer model raises questions about regulation of direct-to-consumer companies, which are outside this case study’s scope.

Compared to prices in the Canadian centers, prices for APOE genetic testing at Athena and at the Saint Louis Center are higher. If the Canadian laboratories’ prices accurately reflect production costs, then testing for APOE can be performed at a lower cost. Prices for health goods and services are lower in Canada across the board, however, so APOE testing is not an exception, but conforms to the rule.

Athena is the only available avenue for PSEN1, PSEN2, and APP testing. The $1675 price for PSEN1 is high relative to APOE genotyping, but it entails genomic sequencing, and this price is comparable to other full-sequence tests for BRCA, colon cancer genes, and spinocerebellar ataxias cited in other case studies. The cost of this testing is out of the financial range of many patients, especially when insurers will not cover “experimental” tests. We simply cannot judge the degree to which threat of patent enforcement explains other laboratories not offering testing for the very rare families with APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations, but it is likely that patent status is just one factor among others such as set-up costs, CLIA certification, ensuring reimbursement, and building a referral network.

Marketing

AD screening in the general population is not recommended at this time. Until recently, any testing for either EOAD or LOAD needed to be done by physician referral, so marketing directly to consumers was a nonissue. Patents do appear to have an effect on marketing to physicians, as Athena has a sales force focused on neurologists for its AD tests, which are just a few among many genetic tests it offers for brain, muscle, endocrine, and nervous system disorders.

Patenting also affected health professional marketing indirectly, by using licensing as a tool for constraining clinical use. Dr. Roses said that a major reason Duke University decided to license exclusively to Athena was to ensure that APOE testing was done in compliance with professional standards (Personal communication with Dr. Allen Roses). While neither Athena nor Duke’s Office of Licensing and Ventures has responded to questions about the licensing terms (Personal communications with Michael Henry, Vice President of Business Development, Athena Diagnostics and with Rose Ritts and Bob Taber, Office of Licensing and Ventures, Duke University), the end result of the exclusive patenting did ensure that testing complied with professional standards, at a time when concern was high that genetic screening for AD could cause fatalism and commercial incentives would militate to overutilization. This fear of widespread testing does not appear to have materialized, as research suggested that “consumers from our focus groups were not interested in testing that could provide neither predictive data nor a reasonably precise answer about their individual risk of developing AD at a particular age” (p. 835).4 This suggests that demand would have been low in any event, but Athena’s policy of requiring physician corroboration of dementia before genetic testing, as Duke University stipulated, was an additional check on testing outside professional standards.

More recently, companies like Graceful Earth, Inc. and Smart Genetics began to offer testing directly to consumers. Smart Genetics is a unique case, since the firm transiently sublicensed from Athena. One of the authors (R. Cook-Deegan) has sought confirmation that terms of the Duke license precluded sublicensing for risk assessment, and those terms were brought to the attention of Athena as a result of action by Allen Roses, the first inventor on the relevant Duke patents. Athena has always been a reference lab only available to physicians.49 Sublicensing to Smart Genetics marked a departure from this policy of ensuring that only individuals with a high likelihood of AD were tested. Both Smart Genetics and Athena received significant press and media coverage from many audiences, including CBS-3, Parade magazine, USA Today, and Science.3, 22, 50, 51 Smart Genetics relied on research published in 2005 and conducted by the REVEAL study, which found that “preliminary analyses suggest that risk assessment and genotype disclosure did not adversely affect the psychological well-being of participants” (p. 254).52

Adoption by Third-Party Payers

For AD, patents have not detectably helped or hindered the decisions by insurance companies to cover LOAD diagnosis using APOE genotype. Almost all major insurers and payers consider APOE testing experimental. In this situation, patents are irrelevant because the service is not covered as medically necessary.

One case where patents might have an impact is with EOAD. Based on its coverage policy for APP and PSEN1, CIGNA Healthcare would likely also cover PSEN2 in “Volga German” family members at risk. Other payers do not have clear policies. Other case studies suggest, however, that so long as prices fall in the range of other genetic tests, patent status would affect access little (and in other cases, pricing has not been clearly associated with patent status).

The main effect of patents is that it enables a sole-provider consolidation of testing, which thereby indirectly links access to coverage and reimbursement (because access is then restricted to the contracts that a sole provider has with payers). If Athena has contracts for payment, then patients would pay a co-payment rather than full cost. If not, patients would bear full costs unless Athena covers them through Athena Access (essentially free or very low cost testing) or its Patient Protection Program (with 20 percent payment up front, but no further direct charges to patients, and refunds if third-party payers later reimburse more than 80 percent). The effect of patents is to block other services from filling in if Athena’s own programs do not meet patient needs, precluding alternative laboratories from testing due to fear of patent infringement liability.

Consumer Utilization

In the case of AD genetic testing, consumer utilization is complicated. Athena does not publicly report utilization rates for APOE, PSEN1, PSEN2, or APP testing (Personal communication with Michael Henry). Athena does report ApoE genotyping utilization to Duke, and presumably reports PSEN1, PSEN2 and APP testing use to the licensors as part of its royalty agreements. Since no academic group is in a position to track those tested, this means Athena is in the best position to inform genetic epidemiology of EOAD and genetic risk of late-onset AD, but unlike Myriad Genetics for BRCA testing, it does not contribute much to the scientific or clinical literature.

The recent rise in direct-to-consumer testing and availability of personal genomics and eventually the broader use of sequencing are likely to increase the number of people who undergo testing, although it will often not be specifically about AD. As Science reported, APOE status was “the only genetic information that James Watson, the DNA discoverer who recently had his entire genome sequenced, kept secret” (p. 1023).53 Watson’s stated purpose was to avoid learning this information himself. Stanley Lapidus adopted this same stance for his “full genome” analysis as part of the Personal Genome Project,54 as did Steven Pinker in his January 2009 feature in the New York Times Magazine.55 It appears that at least for upper income white males past middle age with conspicuous public personae, APOE risk status is a special case.

The extent of testing is highly unpredictable, and will likely depend in part on cost and in part on whether treatments are developed that might reasonably delay the onset of the disease. Patenting could affect access both through price and through single-provider status. And any litigation may also indirectly affect access by limiting the number of providers (but as noted, this does not necessarily imply loss of access). A single provider has strong incentives to advertise and expand market to the point of saturation. A single provider also benefits from establishing an informed network of users (both health professionals and those seeking testing) and securing payment agreements to cover testing with insurers and health plans.

Finally, increased consumer utilization may have an impact on long-term care insurance. In research to find the effect of AD on insurance-purchasing behavior, “Almost 17 percent of those who tested positive subsequently changed their long-term care insurance coverage in the year after APOE disclosure, compared with approximately 2 percent of those who tested negative and 4 percent of those who did not receive APOE disclosure” (p. 487).56 If more people do decide to screen for APOE with the direct-to-consumer companies, long-term care insurance could be affected. The market may stratify according to APOE genotype (with those having an ε4 allele paying more, especially ε4/ε4 homozygotes). This effect, however, is not attributable to patents, but rather to how many people are tested and informed of their AD risk. Any patent effects would be mediated by price or access constraints.

Figure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Drs. Michael Hopkins, Allen Roses, Thomas Bird, Robert Green, and Colm Lawler all kindly reviewed this report.

APPENDIX 1: SYMPTOM CHECKLIST IN THE EVALUATION OF DEMENTIA

Symptom Checklist in the Evaluation of Dementia

| Impaired cognition |

Impaired function |

Mood, mental phenomena |

Behaviors | Drives | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | Cooking | Depression | Low energy level |

Verbal abuse |

Poor appetite |

| Language | Finances | Self- depreciating |

Apathetic | Uncooperative | Weight loss |

| Orientation | Housekeeping | Somatic complaint |

Panic | Physically aggressive |

Excessive appetite |

| Writing, reading |

Shopping | Crying spells |

Labile | “Sundowning” | Hypersexuality |

| Calculating | Driving | Diurnal variation |

Irritable | Demands interaction |

Hyposexuality |

| Recognizing | Hearing and sight |

Withdrawn | Euphoria | Outbursts | Sleeping poorly |

| Attention | Dressing | Anxiety | Delusions | Catastrophic | Excessive sleep |

| Concentration | Mobility (falls) | Fatigues easily |

Illusions | Noisy | Out of bed at night |

| Planning, organizing |

Bathing, grooming |

Death, suicidal |

Rapid speech |

Wandering | |

| Personality change |

Feeding | Disinterested | Hallucinations | Hoarding, rummaging |

|

| Executing | Continence | Anhedonic | Acute confusion |

Sexual aggression |

|

| Social rules | Intrusive | ||||

First published as Table 2.4, Symptom checklist in the evaluation of dementia, p. 29, in Rabins PV, Lykestos CG, Steele CD. Practical Dementia Care 1999. By permission of Oxford University Press, Inc. (www.oup.com)

APPENDIX 2: CRITERIA FOR CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

See Table 1 in McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the Auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–944.

APPENDIX 3: ALGORITHM FOR DEMENTIA EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

[Image: Algorithm for Dementia Evaluation and Diagnosis]

Reproduced with publisher’s permission from p. 24, in Green RC. Diagnosis and Management of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 2nd ed. West Islip, NY: Professional Communications, 2005.

APPENDIX 4: GENETIC TESTING SUMMARY

| Gene | Institution | Cost** | Type | Patents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE | Athena | $475 | SISAR | 5508167 5716828 6027896 |

| Smart Genetics* |

$399 initially, then $249 |

SISAR | Sublicensed from Athena* |

|

| Saint Louis University Health Science Center |

$365 | Targeted Mutation Analysis |

||

| Graceful Earth, Inc. |

$280 | NA | ||

| Sunnybrook Molecular Genetics Laboratory (Canada) |

$120 (CD$)*** |

Targeted Mutation Analysis |

||

| McGill University Health Center (Canada) |

$100 | Targeted Mutation Analysis |

||

| APP | Athena | Sequence Analysis |

None listed | |

| Reproductive Genetics Institute |

~$5,000 | PGD | ||

| PSEN1 | Athena | $1,675 | Sequence Analysis |

6194153 |

| Genesis Genetics Institute |

$2,750 | PGD | ||

| PSEN2 | Athena | Sequence Analysis |

5840540 |

Smart Genetics ceased operations October 2008

All prices in US $ unless otherwise noted

Price in Canadian dollars, approximately $97 in US dollars at exchange rate of $1 Canadian per $.81 US

SISAR: Serial Invasive Signal Amplification Reaction (a method to detect short, targeted sequence variants)

PGD: Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis

Compiled by authors.

APPENDIX 5: EMAIL SENT BY DR. ROBERT COOK-DEEGAN TO ROSE RITTS, DIRECTOR OF DUKE’S OFFICE OF LICENSING AND VENTURES, ON 10 FEBRUARY 2008 (REPEATED 18 OCTOBER 2008)

“Given the potential for confusion here, I think we should resort to formal written questions and answers, so I don't get anything wrong, and so it's all a matter of public record. The federal advisory committee may well want to follow our trail. Feel free to share with your licensee.

I have prepared a list of questions below that will be shared with the Secretary's Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health and Society (SACGHS) on the record. We will share either your reply or we will explain that we got no reply.

The Committee has a task force addressing the impact of patenting and licensing on access to clinical genetic testing, which includes ex officio members from NIH, FDA, CDC, the USPTO and other agencies. You may need to say some information is confidential. That is fine, but being as open as possible would no doubt be welcomed, since this is a federal advisory committee tasked with making recommendations about policy. The more information they have, the more informed their recommendations will be. The responses from Duke and Athena will presumably be interpreted as indicative of how open federal grantees and their licensees are in responding when a researcher requests information pertinent to licensing federally funded inventions, when such research is being carried out on behalf of a federal advisory committee.

Some questions it would be helpful for the task force to answer:

Does Athena Diagnostics report the number of ApoE genotyping tests it does each year? [This query was addressed. The answer was ‘yes.’]

Do those data include aggregated (anonymized) results of those tests that might be relevant to gathering data about allele frequencies in populations tested, or other data relevant to public health?

Will Duke or Athena share those data with the SACGHS task force?

Alan Roses said in his interview that one major reason for licensing exclusively to Athena Diagnostics was to ensure compliance with professional standards emerging at the time, from neurologists' professional organizations and the Stanford group, suggesting ApoE genotyping should only be done in the context of (1) research, or (2) a part of the diagnostic work-up of someone with symptoms of dementia. Was compliance with professional guidelines built into the licensing? How?

If so, what diligence provisions were included in the license? How does Duke monitor compliance with such terms?

The Duke licenses were negotiated in the mid-1990s. A 2005 National Research Council report recommended licensing of genetic diagnostics to permit verification testing, so that exclusive licensees could not block such verification. Did Duke anticipate such a possibility and include provisions in its license? In the wake of the 2005 recommendation, have Duke and Athena discussed bringing this license into agreement with this NRC recommendation?

Now that professional standards are relaxing to use ApoE genotyping for minimal cognitive impairment and for risk profiling without symptoms of dementia, are there mechanisms to adjust the licensing terms to accommodate those changes? Or are the terms of the of the license general enough to permit those changes without renegotiating the license?

Smart Genetics announced last week that it will be offering a risk profile service, with a sublicense from Athena. What arrangements has Smart Genetics made with Athena vis a vis the licensing of APOE testing to asymptomatic individuals, if this was stipulated in the Duke-Athena license (see item 4 above)?

What is the posture of Athena or Smart Genetics with regard to APOE testing being offered as a stand alone test for AD risk by a company like DNADirect or as part of multi-gene panels by DTC companies such as 23andMe, deCODEme, Navigenics, SeqWright, etc.?

If gene panels identify risk markers that are in linkage disequilibrium with ApoE, such as in Coon KD, et al., “A high-density whole-genome association study reveals that APOE is the major susceptibility gene for sporadic late-onset Alzheimer's disease,”57 is that considered testing for ApoE requiring a license from Duke or sublicense from Athena?”

Dr. Michael Henry of Athena Diagnostics spoke with Dr. Cook-Deegan on February 25, 2008, and several times in October and November 2008 about other matters. Answers to these questions (except the partial answer to question 1) have not been received as of 19 January 2009.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

HUMAN STUDIES: All interviews were conducted under Duke University IRB-approved protocol 1277 and usually conducted by phone and recorded. Researchers obtained informed consent from subjects.

FUNDING AND CONFLICT OF INTEREST: This case study was carried out under grant P50 003391, co-funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute and US Department of Energy, and supplemented by funding from The Duke Endowment. The case study authors have no consultancies, stock ownership, grants, or equity interests that would create financial conflicts of interest. The Center for Genome Ethics, Law & Policy accepts no industry funding. Dr. Robert Cook-Deegan is listed on the British Medical Journal roster of physicians who have pledged to remain independent of industry funding <http://www.tseed.com/pdfs/bmj.pdf>.

Contributor Information

Katie Skeehan, Center for Public Genomics, Center for Genome Ethics, Law & Policy, Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy, Duke University.

Christopher Heaney, Center for Public Genomics, Center for Genome Ethics, Law & Policy, Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy, Duke University.

Robert Cook-Deegan, Center for Public Genomics, Center for Genome Ethics, Law & Policy, Institute for Genome Sciences & Policy, Duke University.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Association. [Accessed July 16, 2007];Alzheimer's disease facts and figures 2007: a statistical abstract of U.S. data on Alzheimer's disease. http://alz.org/national/documents/Report_2007FactsAndFigures.pdf.

- 2.Beecham GW, Martin ER, Li Y-J, et al. Genome-wide association study implicates a chromosome 12 risk locus for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 January 9;84(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayden EC. Alzheimer's tests under fire. Nature. 2008 October 30;455(7217):1155. doi: 10.1038/4551155a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Post SG, Whitehouse PJ, Binstock RH, et al. The clinical introduction of genetic testing for Alzheimer disease: an ethical perspective. JAMA. 1997 March 12;277(10):832–836. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.10.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer's Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1363–1371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schutte DL, Holston EC. Chronic dementing conditions, genomics, and new opportunities for nursing interventions. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38(4):328–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird TD. Genetic aspects of Alzheimer disease. Genet Med. 2008;10(4):231–239. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b64dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertram L, Tanzi RE. Alzheimer's disease: one disorder, too many genes? Human Molecular Genetics. 2004;13(Review Issue 1):R135–R141. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strobel G. [Accessed July 16, 2007];What is early-onset familial Alzheimer disease (EFAD)? 2007 April 9; http://www.alzforum.org/eFAD/overview/essay2/default.asp.

- 10.Raux G, Guyant-Marechal L, Martin C, et al. Molecular diagnosis of autosomal dominant early onset Alzheimer's disease: an update. J Med Genet. 2005 October;42:3. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glenner G, Wong C. Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 May 16;120(3):885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glenner G, Wong C. Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 August 16;122(3):1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goate A, Chartier-Harlin M-C, Mullan M, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1991 February 21;349(6311):704–706. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Accessed November 5, 2008];Alzheimer Disease & Frontotemporal Dementia Mutation Database. http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations/default.cfm?MT=1&ML=1&Page=MutByGene.

- 15.Blacker D. New insights into genetic aspects of Alzheimer's disease. Postgrad Med. 2000 October;108(5):119–129. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2000.10.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollen D. Hannah's heirs: the quest for the genetic origins of Alzheimer's disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roses AD. Apoliopoprotein E alleles as risk factors in Alzheimer's disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 1996;47:387–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.47.1.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashford J. APOE genotype effects on Alzheimer's disease onset and epidemiology. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;23(3):157–165. doi: 10.1385/JMN:23:3:157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrer L, Cupples L, Haines J, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between Apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysia. JAMA. 1997 October 22–29;278(16):1349–1356. 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.In Re Bilski, 545 F.3d 943 (Fed Cir. 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanzi RE, Parson AB. Decoding darkness: the search for the genetic causes of Alzheimer’s disease. Cambridge: Perseus; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winik LW, Chen D, Greco P. Intelligence report: a home test for Alzheimer's. Parade. 2008 March 30; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei H-H. [Accessed November 12, 2009];Smart Genetics shuts its doors. October 6; http://www.eyeondna.com/2008/10/06/smart-genetics-shuts-its-doors/

- 24.Genetic testers Smart Genetics closes. Philadelphia Business Journal. 2008 October 3; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leonard D. Patents and licensing fundamentals and the nature of the access problem. [Accessed January 14, 2009];Secretary's Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society. June 27; http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/SACGHS/meetings/June2006/Leonard3.pdf.

- 26. [Accessed November 14, 2008];Athena Diagnostics. Test catalog. http://www.athenadiagnostics.com/content/testcatalog/

- 27.Smart Genetics announces plans to launch a new Alzheimer's risk assessment service; preeminent team of medical advisers helps guide new service offering. PR Newsire. 2008 February 7; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flam F. Genetic test for Alzheimer's divides experts. Philadelphia Inquirer; 2008. Mar 11, p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graceful Earth, Inc. [Accessed November 5, 2008]; http://www.gracefulearth.com/index.asp?PageAction=VIEWPROD&ProdID=3&HS=1.

- 30. [January 16, 2009];Meeting transcript. Secretary's Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and Society. March 1; http://oba.od.nih.gov/oba/sacghs/meetings/March2004/FullDay030104.pdf.

- 31.Risner M, Saunders A, Altman J, et al. Efficacy of rosiglitazone in a genetically defined population with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6(4):9. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roses AD, Saunders A, Huang Y, Strum J, Weisgraber K, Mahley R. Complex disease-associated pharmacogenetics: drug efficacy, drug safety, and confirmation of a pathogenetic hypothesis (Alzheimer's disease) Pharmacogenomics J. 2007;7:10–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roses AD. Commentary on ‘A roadmap for the prevention of dementia: the inaugural Leon Thal Symposium meeting report.’ An impending prevention clinical trial for Alzheimer’s disease: roadmaps and realities. Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 2008 May;4:3. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aetna. [Accessed November 14, 2008];Clinical policy bulletin: Alzheimer’s disease: diagnosis, number: 0349. http://www.aetna.com/cpb/medical/data/300_399/0349.html.

- 35. [Accessed November 12, 2009];Kaiser Permanente. Apolipoprotein E-4 genetic (DNA) test. https://members.kaiserpermanente.org/kpweb/healthency.do?hwid=hw135696§ionId=hw135696-sec&contextId=hw136623.

- 36.CIGNA HealthCare. [Accessed November 14, 2008];CIGNA HealthCare coverage position, coverage position number: 0392. http://www.cigna.com/customer_care/healthcare_professional/coverage_positions/medical/mm_0392_coveragepositioncriteria_genetic_testing_alzheimers.pdf.

- 37.McConnell LM, Koenig B, Greely H, Raffin T. Members of the Alzheimer Disease Working Group of the Stanford Program in Genomics E, and Society. Genetic testing and Alzheimer disease: recommendations of the Stanford Program in Genomics, Ethics, and Society. Genetic Testing. 1999;3(1):3–12. doi: 10.1089/gte.1999.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lovestone S. The genetics of Alzheimer’s disease—new opportunities and new challenges. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.American College of Medical Genetics/American Society of Human Genetics Working Group on ApoE and Alzheimer disease. Statement on use of apolipoprotein E testing for Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 1995 November 22 – 29;274(20):1627–1629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodaty H, Conneally M, Gauthier S, Jennings C, Lennox A, Lovestone S. Consensus statement on predictive testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. Winter. 1995;9(4):182–187. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199509040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Relkin N, Kwon Y, Tsai J, Gandy S. The National Institute on Aging/Alzheimer's Association recommendations on the application of apolipoprotein E genotyping to Alzheimer's disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1996;802:149–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McConnell L, Koenig B, Greely H, Raffin T. Alzheimer Disease Working Group of the Stanford Program in Genomics E, and Society,. Genetic testing and Alzheimer disease: has the time come? Nat Med. 1998;4(7):757–759. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayeux R, Saunders A, Shea S, et al. Utility of the apolipoprotein E genotype in the diagnoisis of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:506–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802193380804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santacruz KS, Swagerty D. Early diagnosis of dementia. Am Fam Physician. 2001 February 15;63(4):703–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liddell MB, Lovestone S, Owen MJ. Genetic risk of Azlehimer's disease: advising relatives. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;(178):7–11. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gosline A. Genome scans go deep into your DNA. Los Angeles Times; 2008. Apr 14, [Google Scholar]

- 47.Navigenics. [Accessed November 12, 2009];Our policy regarding gene patents. http://www.navigenics.com/visitor/what_we_offer/our_policies/gene_patents/

- 48.Cho M, Illangasekare S, Weaver M, Leonard D, Merz J. Effects of patents and licenses on provision of clinical genetic testing services. J Mol Diagn. 2003 February;5(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Athena Diagnostics. [Accessed November 14, 2008];About Athena Diagnostics. http://www.athenadiagnostics.com/content/about/

- 50.Cordes N. [Accessed November 13, 2009];Genetic mapping more hype than help? Looking behind the cost and business of mapping your DNA destiny. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/05/07/eveningnews/main4078733.shtml.

- 51.Rubin R. Want to know if you're destined for Alzheimer's?; Genetic test measures risk factor, but then what do you do? USA Today; 2008. Mar 6, Life: 5D. [Google Scholar]

- 52.REVEAL (Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer's Disease) Study Group. Roberts JS, Cupples LA, Relkin N, Whitehouse P, Green RC. Genetic risk assessment for adult children of people with Alzheimer's disease: the Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer's Disease (REVEAL) study. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005 December;18(4):250–255. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281883. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Couzin J. Once shunned, test for Alzheimer's risk headed to market. Science. 2008 February 22;319(5866):1022–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.319.5866.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lapidus S. [Accessed January 21, 2009];Interpreting the genome (video). Technology Review. http://www.technologyreview.com/Video/?vid=187.

- 55.Pinker S. My genome, my self. New York Times Magazine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zick CD, Mathews CJ, Roberts CJ, Cook-Deegan R, Pokorski RJ, Green RC. Genetic testing for Alzhimer's disease and its impact on insurance purchasing behavior. Health Affairs. 2005 March/April;24(2):483–490. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coon K, Myers A, Craig D, et al. A high-density whole-genome association study reveals that APOE is the major susceptibility gene for sporadic late-onset Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007 April;68(4):613–618. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]