Abstract

Objective

To test whether depression is associated with an increased risk of incident diabetic foot ulcers.

Methods

The Pathways Epidemiologic Study is a population-based prospective cohort study of 4839 patients with diabetes in 2000–2007. The present analysis included 3474 adults with type 2 diabetes and no prior diabetic foot ulcers or amputations. Mean follow-up was 4.1 years. Major and minor depression assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) were the exposures of interest. The outcome of interest was incident diabetic foot ulcers. We computed the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI for incident diabetic foot ulcers, comparing patients with major and minor depression to those without depression and adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, medical comorbidity, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), diabetes duration, insulin use, number of diabetes complications, body mass index, smoking status, and foot self-care. Sensitivity analyses also adjusted for peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease as defined by diagnosis codes.

Results

Compared to patients without depression, patients with major depression by PHQ-9 had a two-fold increase in the risk of incident diabetic foot ulcers (adjusted HR 2.00, 95% CI: 1.24, 3.25). There was no statistically significant association between minor depression by PHQ-9 and incident diabetic foot ulcers (adjusted HR 1.37, 95% CI: 0.77, 2.44).

Conclusion

Major depression by PHQ-9 is associated with a two-fold higher risk of incident diabetic foot ulcers. Future studies of this association should include better measures of peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease, which are possible confounders and/or mediators.

Keywords: diabetes, depression, foot ulcers, complications

Among individuals with diabetes, depression is common and associated with multiple adverse outcomes. Depressive symptoms were associated with a higher risk of developing self-reported macrovascular and microvascular complications in a large study of older Hispanic Americans with type 2 diabetes.1 Mild to severe depressive symptoms were associated with the development of retinopathy2 and proteinuria3 in younger African American adults with type 1 diabetes. In addition, several studies in patients with type 2 diabetes showed that baseline major and minor depression are associated with an increased risk of mortality.1,4–6

The relationship between depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers is not well characterized, however. Cohort studies of patients with prevalent diabetic foot ulcers have shown that depression is associated with larger6 and more severe7 foot ulcers at presentation and a higher risk of nonhealing and recurrent foot ulcers during follow up.7 It is not known whether depression is a risk factor for developing a first diabetic foot ulcer. The purpose of this study was to determine if baseline major and minor depression are associated with an increased risk of incident diabetic foot ulcers using a large cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes.

Research Design and Methods

Setting

Group Health Cooperative (GHC) is a mixed-model prepaid health maintenance organization (HMO) with thirty primary care clinics in western Washington State. Nine GHC primary care clinics were selected for inclusion in the study. Institutional review boards at GHC and the University of Washington approved all study procedures.

Study Cohort Selection

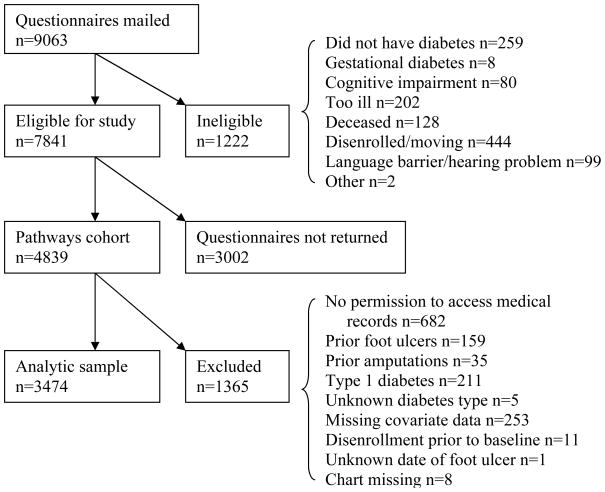

The cohort included in the Pathways Epidemiologic Study has been described in detail elsewhere.8 Briefly, adults in the GHC diabetes registry were invited to participate if they received healthcare between 2000 and 2002 at any of the nine primary care clinics mentioned above. The GHC diabetes registry includes members having any of the following in the preceding 12 months: 1) a dispensed prescription for insulin or an oral hypoglycemic agent, 2) two fasting plasma glucose levels ≥ 126 mg/dl, 3) two random plasma glucose levels ≥ 200 mg/dl, or 4) two outpatient diagnoses of diabetes or any inpatient diagnosis of diabetes. Surveys were mailed to 9063 potentially eligible patients; 1222 were found to be ineligible (Figure). Of 7841 eligible participants, 4839 subjects returned the baseline questionnaire, for a response rate of 61.7% (see Online Appendix A for characteristics of responders versus non-responders). These 4839 participants comprised the Pathways cohort.

Figure.

Recruitment flowchart

Approximately 5 years after enrollment, between 2005 and 2007, we contacted surviving members of the cohort by letter and a follow-up telephone call to ask for permission to review their electronic and paper medical records. Both GHC and University of Washington institutional review boards approved a waiver of consent for participants who died after enrollment in the Pathways cohort. We excluded living participants who did not consent to medical record review (n = 682) and participants with prior diabetic foot ulcers (n = 159), prior amputations (n = 35), type 1 diabetes (n = 211), unknown diabetes type (n = 5), missing covariate data (n = 253), disenrollment prior to baseline (n = 11), unknown date of foot ulcer (n = 1), and missing charts (n = 8) (Figure).

Measures

The predictor of interest, depression at baseline, was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a self-report measure of depression symptoms based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for depression.9 Following the standard method, each item was considered positive if endorsed “more than half the days” in the last two weeks.9 A diagnosis of major depression required at least one of the two cardinal symptoms (depressed mood or loss of interest) and at least five of nine positive symptoms. Criteria for minor depression required at least one cardinal symptom and two to four positive symptoms. Compared to a structured interview major depression diagnosis, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of this PHQ-9 scoring method in a general primary care sample were 88%, 88%, 35%, and 99%, respectively,9 and 35%, 97%, 69%, and 87% in elderly patients with diabetes.10

Participants were screened for diabetic foot ulcers using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (707.1x, 707.8–707.9, 681.1x, 681.9x, 682.7x, 730.06–730.09, 730.17, 730.19, 730.27, 730.29, and 785.4x). Foot ulcer diagnoses were confirmed by chart review and defined as a break in the skin extending through the dermis to deeper tissue (subcutaneous fat, fascia, muscle, joint, or bone) in a location distal to the medial and lateral malleoli that had not healed in 30 days.11 Ulcers above the malleoli, spider bites, malignant neoplasms, vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, venous stasis ulcers, fungal infections, and routine cuts and scratches were not considered diabetic foot ulcers. Prior amputations were defined by diagnosis and procedure codes.

The baseline mailed survey included questions about sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status), diabetes duration, diabetes treatment at diagnosis (none, diet, oral hypoglycemic only, and any insulin), body mass index (BMI), current smoking status, and foot self-care. Foot self-care was ascertained using the two core foot self-care items (the number of days in the past week the participant checked their feet and shoes) from the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities questionnaire.12

Medical record review and automated pharmacy, laboratory, and diagnosis data provided information on use of insulin, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C), and the number of diabetes complications (cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, retinopathy, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, neuropathy, and metabolic) during the twelve months prior to study entry. Patients were classified as having type 1 diabetes if onset was prior to 30 years of age, insulin was the first treatment prescribed, and they were currently taking insulin. For diabetes complications, we used the Diabetes Complications Severity Index,13 modifying cardiovascular disease and stroke using additional chart review data and procedure codes (available upon request) and removing peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease for separate examination. For medical comorbidity, we used the pharmacy-based RxRisk score, an estimate of annual healthcare costs as a function of age, gender, and the chronic condition classes in which prescription fills are observed; higher scores indicate higher medical comorbidity.14 For this study, antidepressants and diabetes medications were not included in the RxRisk score.

Statistical Analyses

SAS/PC for Windows (Stat software version 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. The overall incidence rate for diabetic foot ulcers was calculated by dividing the number of incident foot ulcers by the total person-years of risk. We used Cox regression to model time to incident foot ulcers, censoring at death and disenrollment. All covariates were measured at baseline and chosen a priori. Age, diabetes duration, foot self-care, HbA1c, and BMI were included in the models as continuous variables. We evaluated the proportional hazards assumption using Schoenfeld residuals.

To assess the influence of particular covariates (BMI, smoking status, foot self-care, HbA1c, peripheral arterial disease, and peripheral neuropathy) on the HR for incident diabetic foot ulcers, we used a series of several proportional hazards models, adding the covariates sequentially. The first model was unadjusted. The second model was adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status). In the third model, diabetes severity (diabetes duration, insulin prescription, and number of diabetes complications, excluding peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease, which were added separately later) was added. The remaining covariates were added individually in the following order: BMI, smoking status, foot self-care, HbA1c, peripheral arterial disease, and peripheral neuropathy.

Few amputation events, 25 major (transtibial and above) and 20 minor (ankle or below), precluded meaningful analysis of this outcome.

Sensitivity analyses

We examined death as a competing risk in one sensitivity analysis. We censored individuals at disenrollment but not at death, thus keeping those who died in the risk set. There were no meaningful differences in the estimated association between depression and foot ulcers under the two censoring conditions, indicating that death as a competing risk did not impact the estimated effect of depression on foot ulcer risk.

We did not have standard clinical measures of peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease in our study, but we wanted to examine the effects of adding these possible confounders and/or mediators as defined by diagnostic codes (listed in Online Appendix B). We also assessed the effect of any antidepressant medication use in the year prior to baseline; we did not include antidepressants in our final analysis because treatment with antidepressants in primary care is often simply a marker of depression severity.15 See Online Appendix C for an analysis using continuous PHQ-9.

Results

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of 3474 subjects with type 2 diabetes, 401 (11.5%) had major depression by PHQ-9, 290 (8.3%) had minor depression, and 2783 (80.1%) had no depression. Compared to those without depression, participants with major depression were younger, and participants with minor depression were more often non-white and had longer mean diabetes duration. Compared to those with no depression, subjects with either major or minor depression were more likely to be female, single, less educated, and currently smoking. They also had higher mean BMI, greater medical comorbidity (higher RxRisk scores), and more severe diabetes (higher mean HbA1c, more prescribed insulin, and more diabetes complications). There were no differences in patient-reported foot self-care among the groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants with type 2 diabetes by depressed status, as defined by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9*

| Total sample | Major depression by PHQ-9 | Minor depression by PHQ-9 | No depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 3474 | 401 (11.5) | 290 (8.3) | 2783 (80.1) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 64.1 (12.6) | 59.5 (12.6) | 64.6 (13.2) | 64.7 (12.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 1667 (48.0) | 239 (59.6) | 144 (50.0) | 1284 (46.1) |

| High school education or less, n (%) | 850 (24.5) | 104 (25.9) | 94 (32.4) | 652 (23.4) |

| Not married/living together, n (%) | 1156 (33.3) | 174 (43.4) | 103 (35.5) | 879 (31.6) |

| Non-white, n (%) | 689 (19.8) | 82 (20.4) | 74 (25.5) | 533 (19.2) |

| HbA1c, %, mean (SD) | 7.8 (1.6) | 8.1 (1.7) | 7.9 (1.6) | 7.7 (1.5) |

| Diabetes duration, years, mean (SD) | 8.5(8.2) | 8.4 (6.9) | 9.9 (9.0) | 8.4 (8.3) |

| Prescribed insulin, n (%) | 910 (26.2) | 159 (39.7) | 87 (30.0) | 664 (23.9) |

| Number of diabetes complications† | ||||

| 0 | 1106 (31.8) | 107 (26.7) | 73 (25.2) | 926 (33.3) |

| 1 | 1154 (33.2) | 128 (31.9) | 89 (30.7) | 937 (33.7) |

| 2 | 661 (19.0) | 82 (20.5) | 66 (22.8) | 513 (18.4) |

| 3 | 345 (9.9) | 46 (11.5) | 29 (10.0) | 270 (9.7) |

| 4 | 151 (4.4) | 31 (7.7) | 22 (7.6) | 98 (3.5) |

| 5–7 | 57 (1.6) | 7 (1.7) | 11 (3.8) | 39 (1.4) |

| Peripheral neuropathy‡, n (%) | 494 (14.2) | 80 (20.0) | 58 (20.0) | 356 (12.8) |

| Peripheral arterial disease§, n (%) | 41 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.7) | 35 (1.3) |

| RxRisk score||, US$, n (%) | ||||

| <1300 | 914 (26.3) | 104 (25.9) | 79 (27.2) | 731 (26.3) |

| 1300–2599 | 859 (24.7) | 111 (27.7) | 52 (17.9) | 696 (25.0) |

| 2600–4399 | 818 (23.6) | 67 (16.7) | 73 (25.2) | 678 (24.4) |

| ≥4400 | 883 (25.4) | 119 (29.7) | 86 (29.7) | 678 (24.4) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 31.7 (7.1) | 35.0 (9.0) | 32.5 (7.1) | 31.2 (6.7) |

| Currently smoking, n (%) | 294 (8.5) | 62 (15.5) | 28 (9.7) | 204 (7.3) |

| Foot self-care | ||||

| Checked feet, number of days in last week, mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.7) | 4.5 (2.7) | 4.6 (2.6) | 4.5 (2.7) |

| Checked inside of shoes, number of days in last week, mean (SD) | 2.1 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.8) | 2.0 (2.7) | 2.1 (2.8) |

Column percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) is a self-report measure of depression symptoms based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, (DSM-IV) criteria for diagnosis of a depressive episode.

Retinopathy, cardiovascular disease, stroke, nephropathy, metabolic, peripheral neuropathy, and peripheral arterial disease as defined by diagnosis and procedure codes. Cardiovascular disease and stroke cases were confirmed by chart review.

defined by diagnosis codes

defined by diagnosis and procedure codes

RxRisk is a pharmacy-based measure of medical comorbidity. Higher scores indicate higher medical comorbidity. The score is an estimate of expected annual healthcare costs as a function of age, gender, and the chronic condition classes in which prescription drug fills are observed. Antidepressants and diabetes medications are excluded from this modified RxRisk score.

Mean follow-up was 4.1 years. The unadjusted incidence of diabetic foot ulcers was 8.4/1000 person-years in the entire sample, 16.2/1000 person-years in participants with major depression, 12.1/1000 person-years in participants with minor depression, and 7/1000 person-years in participants without depression.

Table 2 shows estimated hazard ratios (HR) for incident diabetic foot ulcers, comparing major and minor depression to no depression by PHQ-9. Major depression, compared to no depression, was associated with more than twice the hazard for incident foot ulcers (HR 2.17, 95% CI: 1.34, 3.49), after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status), medical comorbidity (RxRisk score), and diabetes severity. This association did not change substantially when potential mediators like foot self-care, BMI, smoking, and HbA1c were added to the model (HR 2.00, 95% CI: 1.24, 3.25). There was no statistically significant association between minor depression by PHQ-9 and incident diabetic foot ulcers (unadjusted HR 1.74, 95% CI: 0.99, 3.06; fully adjusted HR 1.37, 95% CI: 0.77, 2.44). There were no substantial changes in the observed association between major depression by PHQ-9 and diabetic foot ulcers in sensitivity analyses, where we added each of the following covariates sequentially to the full model: peripheral arterial disease (HR 2.09, 95% CI: 1.29, 3.38), peripheral neuropathy (HR 1.99, 95% CI: 1.22, 3.24), and antidepressant use in the year prior to baseline (HR 2.20, 95% CI: 1.33, 3.62)..

Table 2.

Proportional hazards models for risk of incident diabetic foot ulcers in participants with Type 2 diabetes by depressed status, as defined by the PHQ-9

| HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No depression | Major depression by PHQ-9 | Minor depression by PHQ-9 | |

| Model 1 (unadjusted) | 1 (reference) | 2.35 (1.50, 3.68) | 1.74 (0.99, 3.06) |

| Model 2 (Model 1 plus sociodemographic characteristics*) | 1 (reference) | 2.80 (1.76, 4.45) | 1.77 (1.00, 3.14) |

| Model 3 (Model 2 plus RxRisk score) | 1 (reference) | 2.38 (1.49, 3.80) | 1.69 (0.95, 2.98) |

| Model 4 (Model 3 plus diabetes severity†) | 1 (reference) | 2.17 (1.34, 3.49) | 1.43 (0.80, 2.54) |

| Model 5 (Model 4 plus body mass index) | 1 (reference) | 2.07 (1.28, 3.36) | 1.40 (0.79, 2.49) |

| Model 6 (Model 5 plus current smoking status) | 1 (reference) | 2.02 (1.24, 3.27) | 1.40 (0.79, 2.49) |

| Model 7 (Model 6 plus foot self-care‡) | 1 (reference) | 2.02 (1.24, 3.27) | 1.39 (0.78, 2.46) |

| Model 8 (Model 7 plus HbA1c) | 1 (reference) | 2.00 (1.24, 3.25) | 1.37 (0.77, 2.44) |

All covariates were measured at baseline.

sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status

diabetes severity: diabetes duration, prescribed insulin, and number of diabetes complications, excluding peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease, which were added separately in sensitivity analyses.

foot self-care: number of days participant checked feet and number of days participant checked shoes in past week

Conclusions

We found that major depression by PHQ-9 was associated with a two-fold increased risk of incident diabetic foot ulcers among patients with type 2 diabetes over four years. This association persisted after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, diabetes severity (diabetes duration, insulin use, number of complications, and HbA1c), medical comorbidity, BMI, smoking, and patient-reported foot self-care. This finding is consistent with prior cohort studies of patients with prevalent diabetic foot ulcers showing that depression is associated with larger6 and more severe7 foot ulcers at presentation, as well as delayed healing and increased recurrence of foot ulcers.7 To our knowledge, we are the first to examine the association of depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers.

Major foot ulcer risk factors such as peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease could be mediators in a relationship between depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers. Cross-sectional studies have shown that depression is associated with peripheral neuropathy16,17,18 and peripheral arterial disease.19,20,21 In a large, prospective, population-based study of mostly non-diabetic participants, baseline depressive symptoms are linked to the development of incident peripheral arterial disease.22 In addition, a prospective study of veterans, half with diabetes, showed that a history of treated depression is associated with decreased artery patency and recurrent symptoms after revascularization.23 We are aware of no prospective studies showing an association between baseline depression and incident peripheral neuropathy.

Alternatively, symptomatic peripheral neuropathy or peripheral arterial disease could cause depression and thus confound the relationship between depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers. Cross-sectional studies in patients with peripheral arterial disease have shown that decreased lower extremity functioning by 6-minute walk test20,21 and increased self-reported rest pain24 are associated with depressive symptoms, although the directionality of these associations is not clear. A prospective study showed an association between baseline diabetic peripheral neuropathy severity and depressive symptoms 18 months later, and this relationship was partially mediated by the symptoms of pain and unsteadiness.25

Our ability to detect mediation and/or confounding by peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease in sensitivity analyses was limited. We did not have standard clinical measures of neuropathy or peripheral arterial disease. In sensitivity analyses, we used ICD-9-code definitions, which are likely inaccurate compared to standard methods, and found little changes from the results of the main analysis. The relationship between depression and these diabetic foot ulcer risk factors is likely bidirectional and requires further study.

Other potential mediators of a relationship between depression and diabetic foot ulcers include impaired glycemic control and poor self-care, but we found little evidence of this in our study. Depression has been associated with poor glycemic control in several studies.8,26 In our study, depression was associated with modestly higher HbA1c values at baseline, but adding baseline HbA1c to the model made very little difference in the results (Table 2). Depression has been linked with medication nonadherence,27,28 unhealthy diet,27,28 sedentary lifestyle,27,28 obesity,8 smoking,8 and impaired foot-specific self-care28 in patients with diabetes. Studies examining whether improvements in self-care can decrease diabetes foot ulcer rates have had conflicting results.29,30 There was no association between depression and baseline foot-specific self-care in the present study, which is consistent with the findings of other groups,6,27,31 and adding BMI, foot self-care, and smoking to the model did not change the results (Table 2).

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study of the association of depression with incident diabetic foot ulcers. Foot ulcer diagnoses were confirmed by chart review. We did not have structured interview diagnoses of depression, but the PHQ-9 is a well-validated self-report measure of depression.9,10 We also used validated measures of self-care.12 Automated data allowed us to estimate diabetes severity and medical comorbidity.

There are also limitations of our study. We may not have detected incident or prior diabetic foot ulcers if the patient used another healthcare system for care (unlikely in this HMO), did not seek care, or did not receive one of the screening diagnosis codes. Patient characteristics, including depression and other covariates, were measured at baseline only, so we were unable to examine how changes in depression may have affected the risk of incident foot ulcers or fully evaluate mediation by the covariates. As stated above, we did not have reliable diagnoses of possible important confounders and/or mediators like peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease, which could only be measured with ICD-9 codes in our study. The relationship between depression and diabetic foot complications is probably bidirectional, but we were not able to assess this directly. Finally, we analyzed less than 50% of the patients eligible for the original cohort, and the study was completed in one geographic region of the country, possibly limiting generalizability.

Summary

Major depression by PHQ-9 is associated with a two-fold increased risk of incident foot ulcers in patients with type 2 diabetes. Screening for and treatment of depression in patients with diabetes could be helpful in the prevention of foot ulcers, but further studies of this relationship and of the effectiveness of depression screening and treatment in the prevention of foot ulcers are needed before specific clinical recommendations can be made. Future studies of this association should include better measures of peripheral neuropathy and peripheral arterial disease, which are likely important confounders and/or mediators.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant MH-073686. Dr. Williams was supported by National Institutes of Health/American Skin Association grant F32 AR-056380 and a Dermatology Foundation Dermatologist Investigator Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose. All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA. Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2822–2828. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy MS, Roy A, Affouf M. Depression is a risk factor for poor glycemic control and retinopathy in African-Americans with type 1 diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:537–542. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180df84e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy MS, Affouf M, Roy A. Six-year incidence of proteinuria in type 1 diabetic African Americans. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1807–1812. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2668–2672. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin EH, Heckbert SR, Rutter CM, et al. Depression and increased mortality in diabetes - unexpected causes of death. Ann Fam Med. 2009 doi: 10.1370/afm.998. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ismail K, Winkley K, Stahl D, et al. A cohort study of people with diabetes and their first foot ulcer: the role of depression on mortality. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1473–1479. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monami M, Longo R, Desideri CM, et al. The diabetic person beyond a foot ulcer: healing, recurrence, and depressive symptoms. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:130–136. doi: 10.7547/0980130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katon W, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, et al. Behavioral and clinical factors associated with depression among individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:914–920. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamers F, Jonkers CC, Bosma H, et al. Summed score of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 was a reliable and valid method for depression screening in chronically ill elderly patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiber GE, Smith DG, Wallace C, et al. Effect of therapeutic footwear on foot reulceration in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:2552–2558. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young BA, Lin E, Von Korff M, et al. Diabetes complications severity index and risk of mortality, hospitalization, and healthcare utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:15–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care. 2003;41:84–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilchrist G, Gunn J. Observational studies of depression in primary care: what do we know? BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:619–630. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vileikyte L, Leventhal H, Gonzalez JS, et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy and depressive symptoms: the association revisited. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2378–2383. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreira RO, Papelbaum M, Fontenelle LF, et al. Comorbidity of psychiatric disorders and symmetric distal polyneuropathy among type II diabetic outpatients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:269–75. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2007000200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smolderen KG, Aquarius AE, de Vries J, et al. Depressive symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: a follow-up study on prevalence, stability, and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 2008;110:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arseven A, Guralnik JM, O’Brien E, et al. Peripheral arterial disease and depressed mood in older men and women. Vasc Med. 2001;6:229–234. doi: 10.1177/1358836X0100600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, et al. Depressive symptoms and lower extremity functioning in men and women with peripheral arterial disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:461–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wattanakit K, Williams JE, Schreiner PJ, et al. Association of anger proneness, depression and low social support with peripheral arterial disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Vasc Med. 2005;10:199–206. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm622oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherr GS, Wang J, Zimmerman PM, Dosluoglu HH. Depression is associated with worse patency and recurrent leg symptoms after lower extremity revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:744–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smolderen KG, Hoeks SE, Pedersen SS, et al. Lower-leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease are associated with anxiety, depression, and anhedonia. Vasc Med. 2009;14:297–304. doi: 10.1177/1358863X09104658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vileikyte L, Peyrot M, Gonzalez JS, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in persons with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a longitudinal study. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1265–73. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1363-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lustman PJ, Clouse RE, Ciechanowski PS, et al. Depression-related hyperglycemia in type 1 diabetes: a mediational approach. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:195–199. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000155670.88919.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2154–2160. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Delahanty LM, et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self-care in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1102–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lincoln NB, Radford KA, Game FL, Jeffcoate WJ. Education for secondary prevention of foot ulcers in people with diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1954–1961. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malone JM, Snyder M, Anderson G, et al. Prevention of amputation by diabetic education. Am J Surg. 1989;158:520–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston MV, Pogach L, Rajan M, et al. Personal and treatment factors associated with foot self-care among veterans with diabetes. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006;43:227–238. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2005.06.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.