Abstract

Proper modeling of nonspecific salt-mediated electrostatic interactions is essential to understanding the binding of charged ligands to nucleic acids. Because the linear Poisson-Boltzmann equation (PBE) and the more approximate generalized Born approach are applied routinely to nucleic acids and their interactions with charged ligands, the reliability of these methods is examined vis-à-vis an efficient nonlinear PBE method. For moderate salt concentrations, the negative derivative, SKpred, of the electrostatic binding free energy, ΔGel, with respect to the logarithm of the 1:1 salt concentration, [M+], for 33 cationic minor groove drugs binding to AT-rich DNA sequences is shown to be consistently negative and virtually constant over the salt range considered (0.1–0.4 M NaCl). The magnitude of SKpred is approximately equal to the charge on the drug, as predicted by counterion condensation theory (CCT) and observed in thermodynamic binding studies. The linear PBE is shown to overestimate the magnitude of SKpred, whereas the nonlinear PBE closely matches the experimental results. The PBE predictions of SKpred were not correlated with ΔGel in the presence of a dielectric discontinuity, as would be expected from the CCT. Because this correlation does not hold, parameterizing the PBE predictions of ΔGel against the reported experimental data is not possible. Moreover, the common practice of extracting the electrostatic and nonelectrostatic contributions to the binding of charged ligands to biopolyelectrolytes based on the simple relation between experimental SK values and the electrostatic binding free energy that is based on CCT is called into question by the results presented here. Although the rigid-docking nonlinear PB calculations provide reliable predictions of SKpred, at least for the charged ligand-nucleic acid complexes studied here, accurate estimates of ΔGel will require further development in theoretical and experimental approaches.

Introduction

Many important clinical drugs bind noncovalently to the minor groove of B-type DNA duplexes containing three or more consecutive AT basepairs (mG-binders) (1). These small organic drugs are used to treat many conditions, including cancer, genetic disorders, and viral and parasitic diseases. Various structural and biophysical studies have examined the noncovalent interactions that contribute to the binding affinity between the mG-binders and B-DNA (2–4). In particular, the complementarity of both shape and electrostatic potential, as discussed in the Supporting Material, between the drugs and the B-DNA as well as the short-range van der Waals and H-bonding contacts enhance binding affinity and contribute to the base sequence specificity (5–9). These studies, however, do not show the relative importance of these noncovalent interactions in stabilizing drug-DNA complexes (10–12). Understanding how these different interactions contribute to binding at the atomic level is critical to developing novel drugs with enhanced binding affinity, specificity, and biological activity.

Several experimental studies have observed that the binding affinities of mG-binders to B-DNA are very sensitive to small variations in salt concentration. In the literature, this observation has been interpreted to mean that nonspecific electrostatic interactions are important in the formation of these complexes (10,13,14). If Kobs is the experimental binding constant, and [M+] is the concentration of 1:1 salt in the bulk solution, then, in the absence of competing multivalent cations, log(Kobs) is usually proportional to log[M+] over a range of moderate salt concentrations (15,16). The slope of a linear log(Kobs)-log[M+] plot is called SKobs in the literature (17) and is negative for cationic drug-DNA complex formation. A constant negative SKobs over a moderate salt range has historically been interpreted as a characteristic of the polyelectrolyte effect and originates from the high charge density of the negatively charged phosphate groups on the polyanionic DNA backbone (18–20). Because SKobs is easy to obtain experimentally, predicting it is an ideal test of electrostatic models.

The first theoretical attempt to explain the binding of charged ligands to polyelectrolyte DNA was the counterion condensation theory (CCT) developed by Manning (18). The CCT was originally based on a coarse-grained model where the polyion (the DNA in our case) is treated as an infinite line charge representing the projection of the negatively charged phosphate groups onto the helical axis of the DNA. The ionic solvent is modeled as a uniform high dielectric medium, and the ions as point charges. The CCT was later extended by Fenley et al. (21) to account for the 3D arrangement of the phosphate groups obtained from structural data. More recently, others have considered more detailed nonuniform finite charge distributions within the framework of the CCT (22–24), but the CCT lacks features, like full atomic detail and the dielectric discontinuity between the interior and exterior of the molecule, that are important in some predictions of electrostatic properties, like sequence-dependent features of the electrostatic potential and counterion distributions surrounding nucleic acids (6,7,25). Therefore, the CCT may not reproduce experimental data for systems in which these effects are important (26).

According to the Manning CCT (18),

| (1) |

where z is the charge on the cationic drug. Following similar assumptions, Record et al. (20) predict that SKobs = −zψ where ψ is the thermodynamic binding fraction, which depends on the charge density of the nucleic acid. Both theories assume that the polyelectrolyte effect is purely entropic and arises when the ligand displaces counterions that were bound to the DNA before association.

Other interpretations of SKobs have been discussed in the literature. For instance, Anderson and Record (17) express SKobs in terms of preferential interaction coefficients, which take into account changes in the accumulation of cations and the exclusion of anions around the DNA and ligand during binding. If it is assumed that the only salt-dependent terms in the binding free energy are in the electrostatic component of the binding free energy, ΔGel, then, following Sharp et al. (27), SKobs relates to the change in the osmotic pressure on binding, ΔΠ, where Π is the osmotic pressure defined in the Methods section, by:

| (2) |

The Poisson-Boltzmann equation (PBE) (6,28,29) can be solved numerically to find a potential that can be integrated by the methods of Sharp et al. (27) to calculate ΔGel. Unlike the CCT, the PBE can make predictions of ΔGel that include the 3D atomic structure of the biomolecules with low CPU cost due to the algorithmic advances made in the past decade. The PBE does not inherently include conformation change effects. The molecules in this study undergo only very small conformation changes on binding, as pointed out by Wilson et al. (4). Therefore, not including these conformational effects is a reasonable approximation, as we show in the Discussion. PBE methods include both the nonlinear PBE and its linear approximation, which is found by taking the first order approximation to the exponential term in the nonlinear PBE. The linear PBE is valid for small electrostatic potentials. The pairwise generalized Born (GB) method approximates the linear PBE by using an empirical Debye-Hückel term (30,31) to account for nonspecific salt effects.

Some theoretical studies have used the nonlinear PBE to investigate a limited number of drugs binding to nucleic acids (27,28,32–38), whereas several other groups have used either the linear PBE or GB model in lieu of the full nonlinear PBE to study different electrostatic effects in nucleic acids-charged ligand association processes (39–44). Wang and Laughton used molecular dynamics and the molecular mechanics/generalized Born approach to predict the relative affinity of the Hoechst 33258 ligand for different A/T-rich DNA sequences (41). In a newer follow-up study from the same laboratory it was found that predictions of the binding affinity of Hoechst 33258 to different DNA sequences are better when the molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface accessible approach is used as opposed to the molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface accessible approach (45). However, none of these studies have rigorously examined the validity of the linear PBE approximation for a large set of nucleic acid-charged ligand systems. Therefore, one of the main goals in this study is to determine whether the linear PBE provides an adequate approximation to the nonlinear PBE when investigating salt-dependent drug-nucleic acid interactions. Talley et al. (46) did address this question for protein-protein association, but their protein-protein complexes were generally of lower net charge than the complexes examined here. The complexes in this study are therefore expected to exhibit more pronounced nonlinear behavior. To confirm this expectation and to assess the ability of linear and nonlinear PBE analyses to reproduce experimental results, SKobs was calculated with the linear and nonlinear PBE for the complexes in this study.

Unfortunately, extracting ΔGel directly from the experimental data of the binding of charged ligands to nucleic acids is not possible. The CCT predicts that ΔGel can be predicted by

| (3) |

where C is a term that does not depend on the salt concentration. This equation is model-independent, as it is simply a thermodynamic identity. Manning then goes on to compute C by making several assumptions, including that the electrostatic potential can be given by the Debye-Hückel equation and that the atomic structure of neither the polyelectrolyte nor the binding ligand is important to ΔGel. (18) These assumptions lead to the prediction that C is independent of the details of the binding partners and solely depend on the charge density of the polyelectrolyte. Because the PBE does consider this information, C is not necessarily independent of all parameters except the charge density of the polyelectrolyte, and as will be shown here, the PBE predictions of ΔGel do indeed depend on these parameters.

Frequently, experimental groups (47–52) infer ΔGel from the following equation:

| (4) |

which is a simplified version of Eq. 3. Once ΔGel is calculated, the nonelectrostatic binding free energy, ΔGnon-el follows from:

| (5) |

Whether the predictions of Eq. 4 agree with those of the PBE is not clear, however. For instance, from Eq. 4 a larger SKobs indicates a larger ΔGel, but this disagrees with the results of our recent PBE study (53). If Eq. 4 is not valid, then it is not possible to parameterize the PBE directly against the experimental data that has been reported without resolving the term C in Eq. 3. In this study, we report a detailed investigation of the behavior of ΔGel with respect to ln[M+] for a large number of DNA-drug complexes.

Theoretical Methods

The DNA-drug complexes in this study are listed in Table S1, and the atomic coordinates of all the complexes are available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org). The complexes were prepared as described in the Supporting Material.

The PBE calculations were carried out with an adaptive grid solver that is described elsewhere (A. Boschitsch and M. Fenley, unpublished) at 1:1 salt concentrations of 0.1-0.4 M at a temperature of 298 K. This PBE solver produced results that were comparable to the more commonly used APBS (54) PBE solver. The exterior dielectric constant, ɛext, was set at 80, and the interior dielectric constant, ɛint, was fixed at 2. We discuss the effect of ɛint later. The dielectric boundary separating the solute and solvent regions was the solvent excluded, SE, surface. No ion-exclusion region was used because it has a consistent but small effect on our predictions of SKobs (55). The dimensions of the grid were set to three times the largest dimension of the complex, and the fine grid spacing was 0.3 Å. The reader is referred to the Supporting Material for a more detailed description of the PBE calculations.

Results and Discussion

Electrostatic binding free energy of drug-DNA complexes

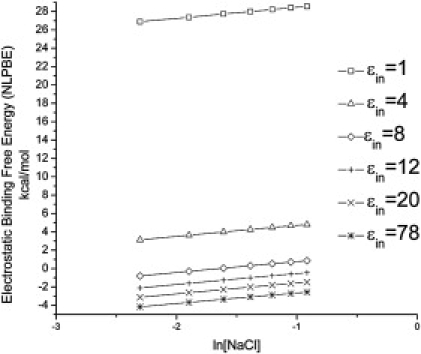

In this study, SKpred is considered rather than ΔGel because ΔGel is sensitive to the PBE parameters. This is illustrated in Fig. 1, where ΔGel is plotted against ln[NaCl] for several values of ɛint for propamidine interacting with AT-rich B-DNA (PDB id: 102D). Unlike ΔGel, which clearly exhibits significant change, the slope of the ΔGel versus ln[NaCl] curves, which is proportional to SKpred, is effectively the same for all ɛint. Comparable variations in ΔGel are observed when varying the dielectric interface definitions used in the PBE calculations (data not shown), although, SKpred is essentially invariant under such changes. Similar conclusions on different nucleic acid-charged ligand systems have been made in other PBE studies (56,57).

Figure 1.

Electrostatic binding free energy, ΔGel (kcal/mol), of the propamidine-B-DNA complex (PDB id: 102D) as a function of the logarithm of the concentration of a 1:1 salt, ln[NaCl] with different internal dielectric constants. ΔGel is highly sensitive to the choice of interior dielectric constant, ɛin, changing from unfavorable to favorable. However, the slope of the lines is fairly constant.

Intuitively, one would expect the desolvation cost to be unfavorable and the Coulombic interactions to be favorable for the association of unlike charges with the net ΔGel remaining small. This expected anticorrelation between the Coulombic term and the reaction field term was observed for the complexes in this study (results not shown), where the Coulombic term is almost equal in magnitude but of opposite sign to the reaction field contribution. This compensation effect between the Coulombic and reaction field energies was first noted by Shaikh et al. (42) and Jayaram et al. (58) in a free energy component analysis of 25 minor groove drug-DNA complexes using a modified GB model (42,58). More recently, a molecular dynamics study of the essential subunit PA-PB1 interaction in the influenza virus RNA polymerase using the molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface accessible and molecular mechanics generalized Born surface accessible protocols also showed this compensation phenomena between the Coulombic and reaction field binding free energies (59). When the drug and the DNA are far apart, there is a net favorable electrostatic binding contribution, originating from the Coulombic term that is only weakly affected by the choice of PBE parameters. As they come in contact however, the unfavorable reaction field term grows and eventually dominates the Coulombic energy contribution. The sensitivity of ΔGel to the parameters is largely attributable to the reaction field contribution. This desolvation energy is also what distinguishes the predictions of the CCT from those of the PBE in a simplistic sense. Because the CCT does not include a dielectric discontinuity, there is no desolvation cost, and therefore the C in Eq. 3 is not dependent on the details of the molecular surface.

Some attempts have been made to identify what surface definition should be used to construct the solute-solvent dielectric boundary in PBE calculations, but the results obtained by different groups are conflicting. In one study, it was found that the van der Waals surface reproduces the effects of charge mutations on the binding affinity of two different RNA-protein complexes better than the SE surface (56). On the other hand, a more recent PBE study of the association of mRNA cap analogs to the translation initiation factor eIF4E showed that both the van der Waals and SE models provide similar predictions of the effects of mutations on the binding energetics (57). Based on these and our own PBE studies (53,60), we believe it is clear that one should be cautious when drawing any conclusions about whether electrostatics stabilizes or destabilizes binding because, by simply altering the dielectric boundary definition and the value of the interior dielectric constant, one can change ΔGel from positive to negative.

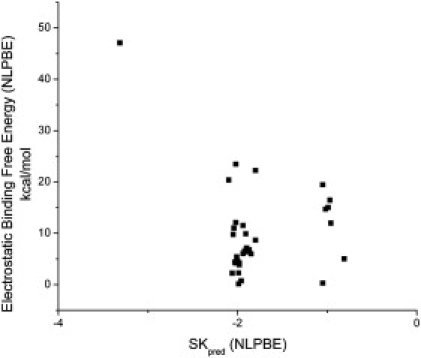

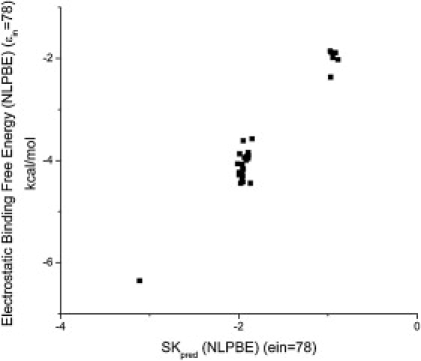

To solve the parameterization problems noted above, one would like to use the reported experimental thermodynamic binding data, but, as mentioned before, the ability of Eq. 4 to predict ΔGel is questionable. As can be seen in Fig. 2, ΔGel and SKpred were not correlated for the choice of PBE parameters listed in the Theoretical Methods section. As has been found in other PBE studies (36,38,61), ΔGel is positive. The problem with Eq. 4 seems to be that it does not account properly for the dielectric discontinuity between the solute and solvent regions. In Fig. 3, ΔGel was plotted against SKpred where each quantity was calculated with an ɛint of 78, so that the dielectric discontinuity was nearly eliminated. This is the limit considered by the CCT, and we would therefore expect Eq. 4 to agree with the predictions of the PBE in this limit. We did not eliminate the dielectric discontinuity completely because this is not possible with our PBE solver, but this should illuminate the behavior in this limit. In this case, ΔGel was strongly correlated with SKpred with an R2 = 0.96. This indicates that the primary difference between the predictions of ΔGel by the CCT and those by the PBE arise from the dielectric discontinuity, whereas incorporating a realistic charge distribution is relatively unimportant. However, several studies have indicated that including a dielectric discontinuity is vital for reproducing other physical parameters (8,62,63), and we therefore do not feel that this choice of ɛin should be used.

Figure 2.

Electrostatic binding free energies, ΔGel (kcal/mol), of all 33 drug-DNA complexes calculated using the nonlinear PBE with a dielectric constant of 2 versus SKpred. These two quantities are not correlated. Therefore, the experimental values of SKobs should not be used to predict the value of ΔGel using Eq. 4 in the main text.

Figure 3.

Electrostatic binding free energies, ΔGel (kcal/mol), of all 33 drug-DNA complexes calculated using the nonlinear PBE with an internal dielectric constant of 78 versus SKpred. Unlike the previous figure, these two quantities are correlated, with an R2 = 0.96. However, it is not clear whether the near lack of a dielectric discontinuity is reasonable.

Effects of the details of the charge distribution on SKpred

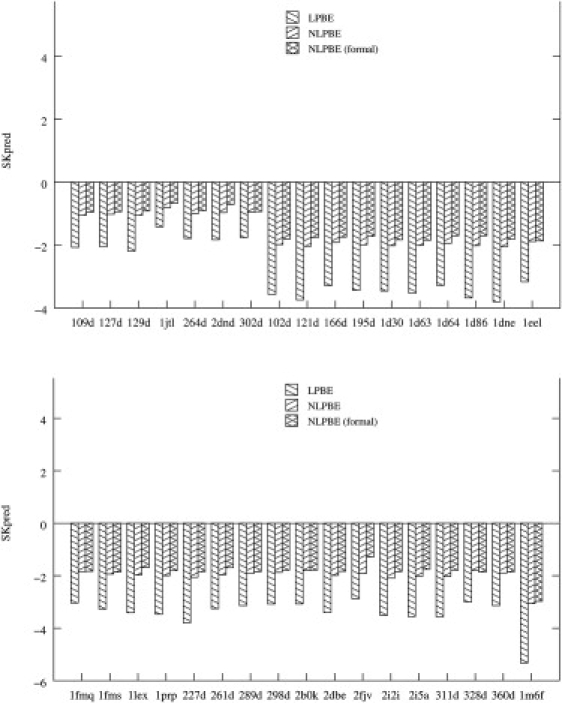

SKpred is fairly independent of changes in the 3D charge distribution that preserve the total charge on the complex, as can be seen from Fig. 4, where SKpred calculated with a formal charge distribution is similar to that obtained using an all-atom charge assignment. These observations concur with an earlier study by Sharp et al. (27) that modeled the binding of DAPI to DNA as a cylinder-sphere interaction and compared the results to a classical all-atom DNA-drug model. They found that SKpred predicted by all-atom models differs by <3% from that obtained with the coarse-grained models. Such errors are less than those in experimental estimates of SKobs. Therefore consideration of full atomic detail does not appear to be necessary when computing SKpred of charged ligand-nucleic acid complexes. Because the charge distribution does not seem to significantly affect SKpred for the complexes in this study, it seems that the ionizable groups are the major contributors to SKpred, with the dipolar groups playing a minor role. A thermodynamic study on the contribution of the closing basepair to the stability of RNA tetraloops supports this observation (64).

Figure 4.

SKpred of all 33 drug-DNA complexes considered here (identified by their PDB ids) and calculated using both the linear PBE and the nonlinear PBE are shown. The nonlinear PBE results obtained with the formal charge assignment for both drug and B-DNA are also shown. The complexes are grouped by net charge, with complexes 109D–302D having a charge of 1e, complexes 102D–360D having a charge of 2e, and complex 1M6F having a charge of 3e.

Comparing the predictions of the nonlinear PBE to experimental binding data

In Table 1, the available thermodynamic salt-dependent binding data for these complexes are compared to our nonlinear PBE predictions, and they are in excellent agreement. This strong correlation between the experimental thermodynamic data obtained from different laboratories and these nonlinear PBE predictions supports the use of the nonlinear PBE in accurately predicting SKobs for these drug-DNA systems. Because the predictions of the linear PBE deviate strongly from the experimental data, the nonlinear PBE should be used for highly charged complexes like these.

Table 1.

Theoretical predictions of the salt dependence of the binding affinity, SKpred, using the NLPBE compared to the available experimental thermodynamic binding affinity data (SKobs) for various minor groove drug-DNA complexes reported in the literature (12,49,74–80)

| PDB name | Experimental SKobs | SKpred (NLPBE) |

|---|---|---|

| 1D30 | −2.3 | −2.0 |

| 1D86 | −1.51; −1.63 | −2.0 |

| 1EEL | ∼−2 | −1.9 |

| 227D | ∼−2 | −2.1 |

| 264D | −0.90; −0.99 ± 0.02 | −1.0 |

| 2DND | −0.79; −0.97 | −0.9 |

| 2B0K | −1.50 ± 0.06 | −1.8 |

| 2DBE | −1.45; −2.02 | −2.0 |

| 2FJV | −1.8 | −1.9 |

| 2I2I | −1.95 ± 0.02; −1.81 ± 0.01 | −2.1 |

| 2I5A | ∼−2 | −2.0 |

NLPBE, nonlinear PBE; PBE, Poisson-Boltzmann equation.

Because predictions from static single-conformation PBE calculations accurately reproduce the experimental data, it appears that conformational flexibility can be neglected for SK predictions in these systems. The role of conformational dependence is more pronounced and its inclusion becomes necessary for more complicated nucleic acid systems where induced fit effects or intercalation are an integral part of the binding mechanism (65).

The reader is referred to the Supporting Material for a comparison of our PBE predictions of SKobs to similar PBE results reported in the literature.

Linear versus nonlinear PBE predictions of SKpred

SKpred obtained with the nonlinear PBE is compared to that obtained with the linear PBE in Fig. 4. For all 33 DNA-drug complexes, the magnitude of SKpred obtained from the linear PBE is larger than that obtained from the nonlinear PBE by at least 51%. This overestimation has also been observed in predictions of SKpred for charged protein-protein complexes (46) and glutamine synthetase and glutaminyl synthetase bound to their cognate tRNA (66). For the protein-protein complexes considered by Talley et al. (46), the overestimation of the magnitude of SKobs using the linear PBE compared with the nonlinear results is much smaller than for the drug-DNA complexes considered here. This is expected, given the larger charge densities of the drug-DNA complexes, and is consistent with the large differences between the linear and nonlinear PBE SK predictions obtained for the more highly charged tRNA synthetase-tRNA complexes examined by Bredenberg et al. (66). The reason why the linear PBE overestimates the magnitude of SKobs is explained using a simple model in the Supporting Material.

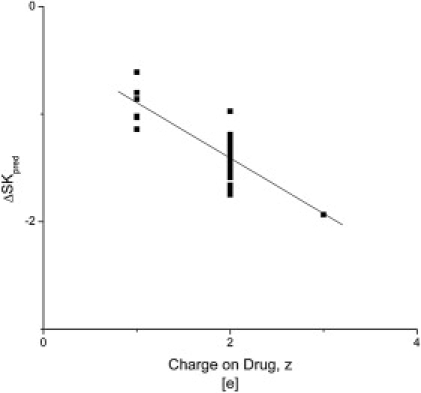

To determine whether the difference between the linear and nonlinear PBE, SKpred is predictable, the difference, ΔSK = SKpred(nonlinear PBE) − SKpred(linear PBE), was calculated as a function of ligand charge. The result, shown in Fig. 5, suggests that ΔSK is proportional to the charge on the ligand. If this pattern holds for other complexes, then the predictions of the linear PBE could be corrected to agree more closely with those of the nonlinear PBE.

Figure 5.

The difference, ΔSKpred, between SKpred calculated with the nonlinear PBE and SKpred calculated with the linear PBE plotted against the charge on the ligand. These quantities seem to be proportional. Therefore, it might be possible to find a way to correct the linear solution to approximate that of the nonlinear PBE.

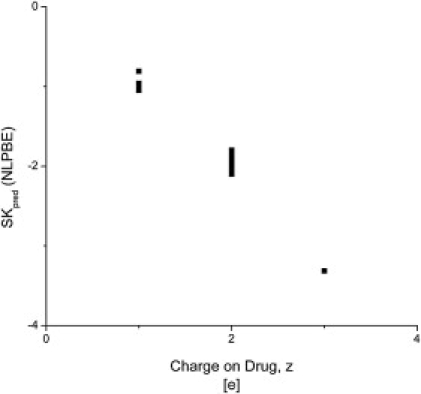

Comparing the nonlinear PBE predictions of SKpred to those of the CCT

In Fig. 6, the values of SKpred are plotted against the net charge of the cationic drug, and the magnitude of SKpred is generally very close to the net charge on the drug, irrespective of the specific charge distribution and geometry of either the drug or the DNA. This result is in good agreement with the CCT and with the PBE analysis carried out by Rouzina and Bloomfield (67) that uses a coarse-grained DNA model. It is indeed striking to see the extent of agreement between the current and previous 3D PBE analyses and CCT predictions given that the 3D PBE and the CCT are based on very different physical models.

Figure 6.

SKpred calculated by the nonlinear PBE is plotted against the charge on the cationic drug, z, for all 33 drug-DNA complexes. SKpred and the net drug charge are clearly correlated, as predicted by the CCT. The slope of the best fit line is −0.99 ± 0.02. This data is in good agreement with the CCT.

Conclusions

The binding of mG-binders was studied using the nonlinear PBE, and these results were used to assess the suitability of using the simpler linear PBE for modeling such systems. We believe the results show clearly that the linear PBE substantially overestimates the magnitude of SKpred with large deviations from the experimental SKobs. On the other hand, the nonlinear PBE provides SKpred results that agree closely with experimental data as well as the predictions of the CCT. Hence, the linear PBE does not provide an adequate description of the electrostatic properties of these complexes.

The nonlinear PBE predictions of SKpred closely matched those of the CCT, whereas the PBE predictions of ΔGel did not agree with those of the CCT. As indicated by our PBE results in the limit of no dielectric discontinuity, this is probably due to the lack of consideration of a low dielectric region in the CCT. The inclusion of a realistic charge distribution had a much smaller effect than the inclusion of a dielectric discontinuity.

This PBE analysis questions the popular method of extracting ΔGel from experimental thermodynamic binding data of charged ligand-nucleic acid complexes, polysaccharides-proteins, and other charged biomolecular complexes (51,68,69). Because the PBE predictions do not agree with Eq. 4, extracting ΔGel directly from thermodynamic binding data is not possible, even though Eq. 4 is used widely (51,69–71) to do this. The common practice of inferring that electrostatic interactions are more important when the magnitude of SKobs is large (72), as implied by Eq. 4, is also questioned by these results, and these concerns should be reexamined by further experimental and theoretical investigations. Also, this work questions the value of obtaining SKobs. Traditionally, it has been valued because of its presumed use to compute ΔGel. If this is not possible, as indicated by these results, then the usefulness of determining SKobs is debatable. The question as to whether electrostatic interactions favor or disfavor the binding of charged ligands to nucleic acids remains unanswered in light of the sensitivity of PBE predictions of ΔGel to various input parameters. Proper parameterization of the PBE together with improved solvent descriptions must be developed and validated against reliable experimental data or all-atom molecular dynamics before these important questions can be answered.

In summary, the nonlinear PBE implementations to treat electrostatic interactions in DNA and DNA-ligand systems have evolved to a stage where reliable predictions of SKpred can be made. However, further advances in a molecular level understanding of binding and, in particular, the effects of solvation (73) seem to be necessary before ΔGel can be reliably computed for biomolecular complexes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. S. A. Shaikh and Ms. T. Singh for providing all the minimized drug-DNA complexes, and E. Bouza and S. Wilches for help in preparing figures and compiling references. We are indebted to A. Silalahi for carrying out the PB calculations for the simple sphere example. We also thank J. Manning for reading the manuscript and providing helpful comments.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (CHEM-0137961 to M.S.C. and M.O.F.), the National Institutes of Health (GM078538-01 to M.O.F.), and the National Institutes of Health Small Business Innovative Research (1R43GM079056 to A.H.B. and M.O.F.).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Chaires J.B. Drug—DNA interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998;8:314–320. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strekowski L., Wilson B. Noncovalent interactions with DNA: an overview. Mutat. Res. 2007;623:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaires J.B. Energetics of drug-DNA interactions. Biopolymers. 1998;44:201–215. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)44:3<201::AID-BIP2>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson W.D., Tanious F.A., Boykin D.W. Antiparasitic compounds that target DNA. Biochimie. 2008;90:999–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu D., Landon T., Fenley M.O. The electrostatic characteristics of G.U wobble base pairs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3836–3847. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boschitsch A.H., Fenley M.O. Hybrid boundary element and finite difference method for solving the nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann equation. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:935–955. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan A.R., Sauers R.R., Olson W.K. Properties of the nucleic-acid bases in free and Watson-Crick hydrogen-bonded states: computational insights into the sequence-dependent features of double-helical DNA. Biophys. Rev. 2009;1:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s12551-008-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohs R., West S.M., Honig B. The role of DNA shape in protein-DNA recognition. Nature. 2009;461:1248–1253. doi: 10.1038/nature08473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu D., Greenbaum N.L., Fenley M.O. Recognition of the spliceosomal branch site RNA helix on the basis of surface and electrostatic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1154–1161. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lane A.N., Jenkins T.C. Thermodynamics of nucleic acids and their interactions with ligands. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2000;33:255–306. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neidle S. Crystallographic insights into DNA minor groove recognition by drugs. Biopolymers. 1997;44:105–121. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazur S., Tanious F.A., Wilson W.D. A thermodynamic and structural analysis of DNA minor-groove complex formation. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:321–337. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hossain M., Kumar G.S. DNA binding of benzophenanthridine compounds sanguinarine versus ethidium: comparative binding and thermodynamic profile of intercalation. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2009;41:764–774. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkar D., Das P., Chattopadhyay N. Binding interaction of cationic phenazinium dyes with calf thymus DNA: a comparative study. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9243–9249. doi: 10.1021/jp801659d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen B., Stanek J., Wilson W.D. Binding-linked protonation of a DNA minor-groove agent. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1319–1328. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin E., Katritch V., Pilch D.S. Aminoglycoside binding in the major groove of duplex RNA: the thermodynamic and electrostatic forces that govern recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:95–110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson C.F., Record M.T., Jr. Salt dependence of oligoion-polyion binding: A thermodynamic description based on preferential interaction coefficients. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:7116–7126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manning G.S. The molecular theory of polyelectrolyte solutions with applications to the electrostatic properties of polynucleotides. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1978;11:179–246. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Record M.T., Jr., Anderson C.F., Lohman T.M. Thermodynamic analysis of ion effects on the binding and conformational equilibria of proteins and nucleic acids: the roles of ion association or release, screening, and ion effects on water activity. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1978;11:103–178. doi: 10.1017/s003358350000202x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Record M.T., Jr., Zhang W., Anderson C.F. Analysis of effects of salts and uncharged solutes on protein and nucleic acid equilibria and processes: a practical guide to recognizing and interpreting polyelectrolyte effects, Hofmeister effects, and osmotic effects of salts. Adv. Protein Chem. 1998;51:281–353. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenley M.O., Manning G.S., Olson W.K. Approach to the limit of counterion condensation. Biopolymers. 1991;30:1191–1203. doi: 10.1002/bip.360301305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manning G.S. Approximate solutions to some problems in polyelectrolyte theory involving nonuniform charge distributions. Macromolecules. 2008;41:6217–6227. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manning G.S. Electrostatic free energy of the DNA double helix in counterion condensation. Biophys. Chem. 2002;101–102:461–473. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schurr J.M., Fujimoto B.S. Extensions of counterion condensation theory I. Alternative geometries and finite salt concentrations. Biophys. Chem. 2002;101–102:425–445. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Min D., Li H., Yang W. Efficient sampling of ion motions in molecular dynamics simulations on DNA: variant Hamiltonian replica exchange method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008;454:391–395. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold B., Marky L.M., Williams L.D. A review of the role of the sequence-dependent electrostatic landscape in DNA alkylation patterns. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19:1402–1414. doi: 10.1021/tx060127n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharp K.A., Friedman R.A., Honig B. Salt effects on polyelectrolyte-ligand binding: comparison of Poisson-Boltzmann, and limiting law/counterion binding models. Biopolymers. 1995;36:245–262. doi: 10.1002/bip.360360211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra V.K., Sharp K.A., Honig B. Salt effects on ligand-DNA binding. Minor groove binding antibiotics. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;238:245–263. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rocchia W., Sridharan S., Honig B. Rapid grid-based construction of the molecular surface and the use of induced surface charge to calculate reaction field energies: applications to the molecular systems and geometric objects. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:128–137. doi: 10.1002/jcc.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasan J., Trevathan M.W., Case D. Application of a pairwise generalized Born model to proteins and nucleic acids: Inclusion of salt effects. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1999;101:426–434. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onufriev A., Bashford D., Case D.A. Modification of the generalized Born model suitable for macromolecules. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:3712–3720. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Misra V.K., Honig B. On the magnitude of the electrostatic contribution to ligand-DNA interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:4691–4695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baginski M., Polucci P., Martelli S. Binding free energy of selected anticancer compounds to DNA—theoretical calculations. J. Mol. Model. 2002;8:24–32. doi: 10.1007/s00894-001-0064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baginski M., Fogolari F., Briggs J.M. Electrostatic and non-electrostatic contributions to the binding free energies of anthracycline antibiotics to DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;274:253–267. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen S.W., Honig B. Monovalent and divalent salt effects on electrostatic free energies defined by the nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann equation: application to DNA binding reactions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:9113–9118. [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Castro L.F., Zacharias M. DAPI binding to the DNA minor groove: a continuum solvent analysis. J. Mol. Recognit. 2002;15:209–220. doi: 10.1002/jmr.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohs R., Sklenar H., Roder B. Methylene blue binding to DNA with alternating GC base sequence: a modeling study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2860–2866. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kostjukov V.V., Khomytova N.M., Evstigneev M.P. Electrostatic contribution to the energy of binding of aromatic ligands with DNA. Biopolymers. 2008;89:680–690. doi: 10.1002/bip.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spacková N., Cheatham T.E., 3rd, Sponer J. Molecular dynamics simulations and thermodynamics analysis of DNA-drug complexes. Minor groove binding between 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and DNA duplexes in solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1759–1769. doi: 10.1021/ja025660d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S.Y., Lin T.H. Molecular dynamics study on the interaction of a mithramycin dimer with a decanucleotide duplex. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:9764–9772. doi: 10.1021/jp045171v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H., Laughton C.A. Molecular modelling methods for prediction of sequence-selectivity in DNA recognition. Methods. 2007;42:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaikh S.A., Ahmed S.R., Jayaram B. A molecular thermodynamic view of DNA-drug interactions: a case study of 25 minor-groove binders. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;429:81–99. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaikh S.A., Jayaram B. A swift all-atom energy-based computational protocol to predict DNA-ligand binding affinity and ΔTm. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2240–2244. doi: 10.1021/jm060542c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treesuwan W., Wittayanarakul K., Mackay S.P. A detailed binding free energy study of 2:1 ligand-DNA complex formation by experiment and simulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:10682–10693. doi: 10.1039/b910574c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H., Laughton C.A. Evaluation of molecular modelling methods to predict the sequence-selectivity of DNA minor groove binding ligands. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:10722–10728. doi: 10.1039/b911702d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talley K., Kundrotas P., Alexov E. Modeling salt dependence of protein-protein association: linear vs. non-linear Poisson-Boltzmann equation. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2008;3:1071–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nguyen B., Hamelberg D., Wilson W.D. Characterization of a novel DNA minor-groove complex. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1028–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(04)74178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaires J.B. Calorimetry and thermodynamics in drug design. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:135–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Breslauer K.J., Remeta D.P., Marky L.A. Enthalpy-entropy compensations in drug-DNA binding studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:8922–8926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haq I., Ladbury J. Drug-DNA recognition: energetics and implications for design. J. Mol. Recognit. 2000;13:188–197. doi: 10.1002/1099-1352(200007/08)13:4<188::AID-JMR503>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prevette L.E., Lynch M.L., Reineke T.M. Correlation of amine number and pDNA binding mechanism for trehalose-based polycations. Langmuir. 2008;24:8090–8101. doi: 10.1021/la800120q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hossain M., Suresh Kumar G. DNA intercalation of methylene blue and quinacrine: new insights into base and sequence specificity from structural and thermodynamic studies with polynucleotides. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:1311–1322. doi: 10.1039/b909563b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bredenberg J., Fenley M.O. Salt dependent association of novel mutants of TATA-binding proteins to DNA: predictions from theory and experiments. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2008;3:1132–1153. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker N.A., Sept D., McCammon J.A. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boschitsch A.H., Fenley M.O. A new outer boundary formulation and energy corrections for the nonlinear Poisson-Boltzmann equation. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:909–921. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qin S., Zhou H.-X. Do electrostatic interactions destabilize protein-nucleic acid binding? Biopolymers. 2007;86:112–118. doi: 10.1002/bip.20708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Szklarczyk O., Zuberek J., Antosiewicz J.M. Poisson-Boltzmann model analysis of binding mRNA cap analogues to the translation initiation factor eIF4E. Biophys. Chem. 2009;140:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jayaram B., McConnell K., Beveridge D.L. Free-energy component analysis of 40 protein-DNA complexes: a consensus view on the thermodynamics of binding at the molecular level. J. Comput. Chem. 2002;23:1–14. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu H., Yao X. Molecular basis of the interaction for an essential subunit PA-PB1 in influenza virus RNA polymerase: Insights from molecular dynamics simulation and free energy calculation. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7:75–85. doi: 10.1021/mp900131p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bredenberg J.H., Russo C., Fenley M.O. Salt-mediated electrostatics in the association of TATA binding proteins to DNA: a combined molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann study. Biophys. J. 2008;94:4634–4645. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.125609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rohs R., Sklenar H. Methylene blue binding to DNA with alternating AT base sequence: minor groove binding is favored over intercalation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2004;21:699–711. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2004.10506960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elcock A.H., McCammon J.A. The low dielectric interior of proteins is sufficient to cause major structural changes in DNA on association. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:3787–3788. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Honig B., Nicholls A. Classical electrostatics in biology and chemistry. Science. 1995;268:1144–1149. doi: 10.1126/science.7761829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blose J.M., Proctor D.J., Bevilacqua P.C. Contribution of the closing base pair to exceptional stability in RNA tetraloops: roles for molecular mimicry and electrostatic factors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8474–8484. doi: 10.1021/ja900065e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frankel A.D., Kim P.S. Modular structure of transcription factors: implications for gene regulation. Cell. 1991;65:717–719. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90378-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bredenberg J., Boschtisch A.H., Fenley M.O. The role of anionic protein residues on the salt dependence of the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to tRNA: a Poisson-Boltzmann analysis. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2008;3:1051–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rouzina I., Bloomfield V.A. Influence of ligand spatial organization on competitive electrostatic binding to DNA. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:4305–4313. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahl I.M., Jonsson B.H., Tibell L.A.E. Thermodynamic characterization of the interaction between the C-terminal domain of extracellular superoxide dismutase and heparin by isothermal titration calorimetry. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9932–9940. doi: 10.1021/bi900981k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Richard B., Swanson R., Olson S.T. The signature 3-O-sulfo group of the anticoagulant heparin sequence is critical for heparin binding to antithrombin but is not required for allosteric activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:27054–27064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.029892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin P.H., Tong S.J., Chen W.Y. Thermodynamic basis of chiral recognition in a DNA aptamer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009;11:9744–9750. doi: 10.1039/b907763d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chernatynskaya A.V., Deleeuw L., Lane A.N. Structural analysis of the DNA target site and its interaction with Mbp1. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4981–4991. doi: 10.1039/b912309a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhadra K., Maiti M., Kumar G.S. Berberine-DNA complexation: new insights into the cooperative binding and energetic aspects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1780:1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reddy C.K., Das A., Jayaram B. Do water molecules mediate protein-DNA recognition? J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:619–632. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang L., Kumar A., Wilson W.D. Comparative thermodynamics for monomer and dimer sequence-dependent binding of a heterocyclic dication in the DNA minor groove. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:361–374. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson W.D., Tanious F.A., Strekowski L. DNA sequence dependent binding modes of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) Biochemistry. 1990;29:8452–8461. doi: 10.1021/bi00488a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haq I., Ladbury J.E., Chaires J.B. Specific binding of Hoechst 33258 to the d(CGCAAATTTGCG)2 duplex: calorimetric and spectroscopic studies. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;271:244–257. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miao Y., Lee M.P.H., Wilson W.D. Out-of-shape DNA minor groove binders: induced fit interactions of heterocyclic dications with the DNA minor groove. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14701–14708. doi: 10.1021/bi051791q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pilch D.S., Kirolos M.A., Breslauer K.J. Berenil [1,3-bis(4′-amidinophenyl)triazene] binding to DNA duplexes and to a RNA duplex: evidence for both intercalative and minor groove binding properties. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9962–9976. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tanious F.A., Laine W., Wilson W.D. Unusually strong binding to the DNA minor groove by a highly twisted benzimidazole diphenylether: induced fit and bound water. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6944–6956. doi: 10.1021/bi700288g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miao Y. Chemistry. Georgia State University; Atlanta, GA: 2006. Shape-dependent molecular recognition of specific sequences of DNA by heterocyclic cations. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.