Abstact

The structural mechanics of tropomyosin are essential determinants of its affinity and positioning on F-actin. Thus, tissue-specific differences among tropomyosin isoforms may influence both access of actin-binding proteins along the actin filaments and the cooperativity of actin-myosin interactions. Here, 40 nm long smooth and striated muscle tropomyosin molecules were rotary-shadowed and compared by means of electron microscopy. Electron microscopy shows that striated muscle tropomyosin primarily consists of single molecules or paired molecules linked end-to-end. In contrast, smooth muscle tropomyosin is more a mixture of varying-length chains of end-to-end polymers. Both isoforms are characterized by gradually bending molecular contours that lack obvious signs of kinking. The flexural stiffness of the tropomyosins was quantified and evaluated. The persistence lengths along the shaft of rotary-shadowed smooth and striated muscle tropomyosin molecules are equivalent to each other (∼100 nm) and to values obtained from molecular-dynamics simulations of the tropomyosins; however, the persistence length surrounding the end-to-end linkage is almost twofold higher for smooth compared to cardiac muscle tropomyosin. The tendency of smooth muscle tropomyosin to form semi-rigid polymers with continuous and undampened rigidity may compensate for the lack of troponin-based structural support in smooth muscles and ensure positional fidelity on smooth muscle thin filaments.

Introduction

The actin-binding protein tropomyosin is found in virtually all cells (1,2). The 40 nm long coiled-coil molecule, referred to here as a monomer, links together end-to-end to form polymeric strands that associate longitudinally along the sides of actin filaments (3–5). The presence of the tropomyosin strands on actin-containing thin filaments has two major effects. Tropomyosin strengthens the filaments by increasing their mechanical stiffness (6,7) while at the same time it acts as a variable filter to regulate the binding of other actin-binding proteins onto the filament surface (3–5,8–10). Even though tropomyosin is highly conserved, over 40 tropomyosin isoforms occur in mammalian cells, which represent the product of multiple genes and alternative transcriptional splicing (1,2). Of all the different isoforms characterized to date, cardiac and skeletal muscle tropomyosins are the best understood in terms of structure and function. In concert with troponin, and responding to varying Ca2+ concentration, striated muscle tropomyosin alternatively blocks or opens myosin-binding sites on actin to inhibit or activate myosin crossbridge cycling and consequently relax or promote muscle contractility (3–5,8–12). Although it is less well recognized, the role played by tropomyosin in troponin-free smooth muscle filaments is no less significant, as the presence of tropomyosin on actin in all muscle types is inhibitory at low myosin levels and potentiating at high ones. Thus, at a very fundamental level, tropomyosin is responsible for the cooperativity of the myosin-actin interaction and the effectiveness of on-off switching of muscle contractions (13,14). Hence, despite the absence of troponin in smooth muscle, smooth muscle tropomyosin still participates as a regulator of muscle activity. Although smooth muscles are mainly governed by myosin phosphorylation and not Ca2+ binding to troponin (14,15), the cooperativity conferred on actomyosin interactions by tropomyosin presumably decreases the intracellular Ca2+ concentration range and the extent of myosin phosphorylation over which smooth muscle activation and relaxation occurs, and thus the efficacy of the overall on-off switching process. It follows that smooth muscle (and presumably nonmuscle) tropomyosin is more than just a passive device designed to strengthen actin filaments and/or protect them from depolymerizing and remodeling factors.

F-actin only binds tropomyosin effectively once tropomyosin is linked together end-to-end; in contrast, the association of F-actin with individual tropomyosin molecules is extremely weak (16). In skeletal and cardiac muscle, tropomyosin is further stabilized on actin filaments by being buttressed by the troponin T subunit of troponin (TnT). In fact, the N-terminal tail of TnT (TnT1) associates with and lies over the tropomyosin end-to-end links. Thus this domain is likely to strengthen striated muscle tropomyosin end-to-end connectivity, thereby reducing the tendency of individual tropomyosin molecules to dissociate from F-actin (17). The N- and C-terminal ends of different tropomyosin isoforms show sequence variation. Sequence specialization in smooth muscle tropomyosin, for example, may lead to tighter end-to-end linkages, thus compensating for the lack of TnT-linked stabilization in the smooth muscles (18). Moreover, the enhanced end-to-end binding strength may contribute to smooth muscle tropomyosin's positional fidelity on actin (19) and explain its precise localization on reconstituted thin filaments. In fact, structural studies suggest that cardiac tropomyosin localization is less well defined on actin in the absence of troponin than is smooth muscle tropomyosin (19).

We previously showed that αα-striated muscle tropomyosin is a gradually curved, semi-rigid molecule with a relatively high persistence length (20,21). In the work presented here, we studied electron microscopy (EM) images of the smooth muscle αβ-isoform of tropomyosin to assess the end-to-end interaction and persistence length of these molecules. We show that, like striated muscle tropomyosins, the smooth muscle tropomyosin molecules are also smoothly curved, without any obvious signs of kinking or extra bending. We find that although the persistence length of the smooth muscle tropomyosin is about the same as that of the αα-striated muscle tropomyosin, the end-to-end linkage responsible for smooth muscle tropomyosin polymerization is considerably stiffer. The stiffer end-to-end association presumably allows the smooth muscle tropomyosin to behave mechanically as a continuous rod, despite the lack of TnT reinforcement, and thus assists in ensuring effective polymeric associations with F-actin in smooth muscles cells. Our results thus provide new insights into the assembly and function of the smooth thin filaments.

Materials and Methods

Electron microscopy and image analysis

Samples of bovine cardiac tropomyosin (>90% αα-isoform) and chicken gizzard smooth muscle tropomyosin (an αβ-heterodimer) were purified according to Tobacman and Adelstein (22) and Jancsó and Graceffa (23), and rotary-shadowed (24,25) using the following procedure: Samples diluted to 1.0 μM in a solution consisting of 5 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, and 30% glycerol were sprayed onto freshly cleaved mica (some samples contained 100 mM KCl to test the effects of higher ionic strength). The proteins were allowed to dry for ∼10–20 min and then placed in an Edward's vacuum evaporator (BOC Edwards, Wilmington, MA) to achieve a vacuum lower than 5 × 10−6 Torr (glycerol was typically included in the preparations to prevent drying artifacts during evacuation (26–28)). A total of 9 mg of platinum was evaporated over a 1 min period from a distance of 9.5 cm at a 9° angle onto the rotating samples, and thin carbon was then deposited over the platinum replica. The carbon-supported platinum replica was floated off the mica onto water and adsorbed onto 400 mesh copper grids. EM was carried out on the shadowed molecules with the use of a Philips CM120 electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) at 120 kV, and images were digitized at 28,000× magnification with a 2Kx2K F224HD slow-scan CCD camera (TVIPS, Gauting, Germany). The recorded images of tropomyosin were then skeletonized after manual selection of 0.5 × 0.5 nm points every 4–5 nm along the center of the protein's longitudinal axis (20,21). The persistence length, ξ, was calculated using the tangent angle correlation method, after θ (the deviation angles along tropomyosin from an idealized straight rod) was determined for segment lengths between 50 and 250 nm. Previously developed algorithms specifically tailored to determine ξ and θ (20,21) were used. Plots relating the inverse slope of 〈ln(cos θ)〉 to the segment length yielded the persistence length values, where the factor of 2 in accounts for the two-dimensionality of the images (20,21).

Molecular-dynamics simulation

A molecular-dynamics (MD) simulation was run on a homology model of αβ-chicken gizzard tropomyosin that had been constructed to match the structure of a previously determined atomic model of αα-cardiac tropomyosin (20). Each amino acid residue in the first of the two α-helices of the cardiac tropomyosin template was replaced by a corresponding residue in the α-chain of the chicken gizzard tropomyosin sequence (18), and then the second helix in the coiled-coil was constructed analogously from the gizzard β-chain. The starting structure was energy-optimized and the MD simulation was run for 35 ns at 300° K with Langevin dynamics and an implicit solvent model using the program CHARMM c33b2 (29) as described previously (20). The apparent persistence length, ξa, was determined via tangent correlation analysis from θ (deviation angles of individual MD conformers from an idealized straight rod), and the dynamic persistence length ξd was calculated from δ (deviation angles of individual conformers from the average longitudinal trajectory of all conformers over the production run) as detailed in previous studies (20,21). Methods to determine ξd from low-resolution, two-dimensional projections of curved rods, such as tropomyosin in EM images, have not been described.

Results and Discussion

Electron microscopy

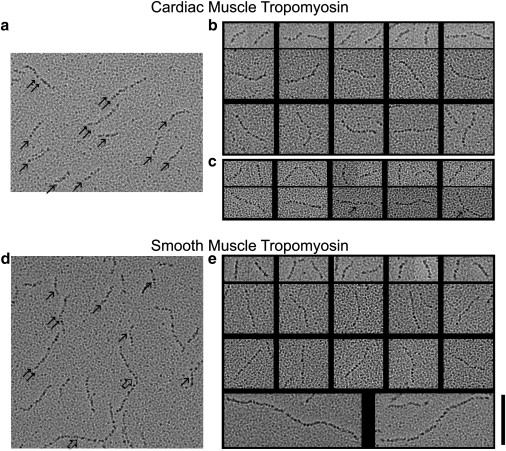

EM of rotary-shadowed tropomyosin samples is an ideal method to reveal the outlines of elongated molecules such as tropomyosin at ∼4–5 nm resolution (24–28). In contrast to negative staining of single molecules (20), which presents difficulties in controlling grid surface properties and stain thickness, rotary shadowing provides consistently reliable results. In this study, platinum shadowing and EM were performed to capture images of purified cardiac αα-tropomyosin and gizzard smooth muscle αβ-tropomyosin. The single coiled-coil molecules thus observed are referred to here as monomers, and end-to-end linked molecules as dimers, trimers, or polymers. EM shows that cardiac tropomyosin (and skeletal tropomyosin; not shown) consists primarily of 40 nm long monomers, with some occasional dimers and short oligomers (∼15% of cases). Conversely, EM shows smooth muscle tropomyosin to be a mixture of variable-length polymeric chains of end-to-end linked molecules found together with fewer single molecules, dimers, and short oligomers (∼65% of the particles observed are oligomeric or polymeric; Fig. 1, Table 1). In all cases, both the well-separated single molecules and the end-to-end polymers show smoothly curved profiles and lack obvious signs of kinks or joints (Fig. 1). No extremely bent monomers or jointed molecular chains are seen. This suggests that tropomyosin molecules remain intact and relatively rigid even after they are adsorbed and dried onto a mica substrate before platinum shadowing is performed.

Figure 1.

EM of isolated tropomyosin molecules. (a and b) Rotary-shadowed bovine cardiac tropomyosin molecules. (c) Rotary-shadowed cardiac tropomyosin complexed with TnT. (d and e) Chicken gizzard smooth muscle tropomyosin molecules. (a and d) Survey fields showing monomers (single arrows), dimers (double arrows), and polymers (open arrows). (b, c, and e) Montages showing examples of monomers, dimers, and polymers. (b) Top row: cardiac tropomyosin monomers; bottom two rows: dimers. (c) Top row: cardiac tropomyosin monomers complexed with TnT; bottom row: dimers with TnT (arrow indicates possible contribution of TnT at the center region of the dimers). (e) Top row: gizzard tropomyosin monomers; middle two rows: dimers; bottom row: polymers. Scale bar: 100 nm for each set of images. Molecules were examined from two or more different protein preparations each.

Table 1.

Polymer length distribution of cardiac and smooth muscle tropomyosin

| Tropomyosin type | Monomers | Dimers | Trimers | Multimers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac muscle | 476 | 80 | 16 | 2 |

| Smooth muscle | 242 | 111 | 45 | 41 |

Frequency of monomers, dimers, trimers, and longer polymers found in EM samples of cardiac and smooth muscle tropomyosin.

Persistence length evaluation of tropomyosin monomers

To quantify the flexibility of tropomyosin, the apparent persistence length of shadowed tropomyosin molecules was determined. The persistence length is a measure of a rod's deviations from a straight reference of similar dimensions, and was ascertained here after >100 images of cardiac and smooth muscle tropomyosin monomers were skeletonized (20). The 102 nm value for the persistence length of cardiac tropomyosin (Table 2) obtained by the tangent correlation method (see Materials and Methods) is almost identical to the 104 nm value obtained previously for the αα-tropomyosin isoform preserved in negative stain (20). The 107 nm persistence length measured for shadowed images of smooth muscle tropomyosin monomers is also virtually the same as these values (Table 2). Within the precision of our methods, changing the monovalent ion concentration from 5 mM to 100 mM KCl in the buffer used to suspend tropomyosin had no effect on the persistence length of tropomyosin. A comparison of the contour length of the tropomyosin monomers (i.e., the full distance measured along their curved profiles) with their end-to-end length (i.e., the shortest distance measured between their two ends) provides an estimate of molecular bending. On average, this ratio is 1.042 and 1.041 for the cardiac and smooth muscle tropomyosin monomers present in the EMs. This remarkable similarity suggests that the two monomer species exhibit closely matching average contours and flexibility.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of cardiac and smooth muscle tropomyosins

| Tropomyosin samples examined by EM | N∗ | Persistence length (ξ) | Bendingangle (θ)† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac muscle monomers‡ | 109 | 102 nm | – |

| Smooth muscle monomers§ | 159 | 107 nm | – |

| Cardiac muscle dimers (distal parts) | 132 | 108 nm | 27.4° |

| Cardiac muscle dimers (central part) | 66 | 63 nm | 35.9° |

| Cardiac muscle dimers + TnT1 (distal parts)¶ | 144 | 98 nm | 28.9° |

| Cardiac muscle dimers + TnT1 (central part)¶ | 72 | 106 nm | 27.8° |

| Smooth muscle dimers (distal parts)‖ | 136 | 107 nm | 27.6° |

| Smooth muscle dimers (central part)‖ | 68 | 123 nm | 25.7° |

Number of molecules or segments analyzed.

The average end-to-end bending angle over 25 nm arc length segments was calculated from the persistence lengths using the equation ξ= arc length/〈θ〉2, and confirmed by measuring and averaging the differences in angular orientation between the two ends of each segment, as in Li et al. (20).

ξa for MD conformers is 101 nm (20).

ξa for MD conformers is 104 nm.

An expressed TnT1 fragment representing the N-terminal 153 residues of cardiac TnT, prepared by Hinkle et al. (41), was added to cardiac tropomyosin at a 3:1 molar ratio to ensure complex formation at the low concentrations used for EM studies. The tropomyosin-TnT complex was then rotary-shadowed and the distal and central parts of 80 nm long complexes (i.e., tropomyosin dimers with associated TnT1) were analyzed.

The values noted are for tropomyosin samples suspended in a solution containing 5 mM KCl; raising KCl to 100 mM had a minimal effect on the persistence length of the distal or central parts of the dimers (ξ = 95 nm and 114 nm at 100 mM KCl, respectively). Comparable trials in which the salt concentration of cardiac tropomyosin was increased were not practical, since relatively few dimers were then noted.

Persistence length evaluation of the tropomyosin dimers

Determining the persistence length over both the coiled-coil section of tropomyosin and the intervening end-to-end junctions should provide pertinent clues about the mechanics of tropomyosin polymers. Indeed, end-to-end linked tropomyosin dimers have the simplest unit dimensions needed to assess the regional differences that then characterize tropomyosin filaments. Even though much of shadowed cardiac tropomyosin is monomeric, cardiac dimers are observed with sufficient frequency for such an analysis to be carried out. In addition, a corresponding assessment of smooth muscle tropomyosin dimers found among longer polymers can also be made.

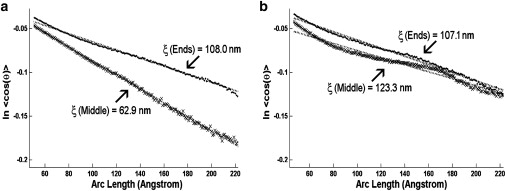

We analyzed and compared 25 nm stretches over the distal end section of dimeric tropomyosin and over the central region of the dimers (i.e., where the respective coiled-coiled structure and end-to-end links lie). When tropomyosin was further subdivided, the data became noisy. Conspicuously, the 63 nm persistence length found over the 25 nm central region stretches of cardiac tropomyosin is considerably lower than the 108 nm value determined for the distal regions of the cardiac dimers, whereas the latter value is comparable to that of monomeric tropomyosin. As expected, the persistence length of the central region of the cardiac dimers increases to that of the rest of the molecule when the tropomyosin is in a complex with and buttressed by the TnT1 fragment of TnT (Table 2, Fig. 2 a). In marked contrast, the persistence lengths of the ends and the central region of the smooth muscle dimers are about the same, despite the absence of troponin or any other accessory proteins. If anything, the persistence length over the central region containing the end-to-end association is greater (123 nm), not smaller, than any of the other stretches examined, as would be likely if the smooth muscle tropomyosin linkage were particularly stiff (Table 2, Fig. 2 b). This strong end-to-end association is minimally affected by an increase in the monovalent ion concentration of the tropomyosin buffer (Table 2), suggesting that, once formed, end-to-end linkages are relatively stable in the different buffers (e.g., the persistence length for the central region of smooth muscle tropomyosin is 123 nm at 5 mM KCl and 114 nm at 100 mM KCl).

Figure 2.

Apparent persistence length measurements of rotary-shadowed tropomyosin dimers. The tangent correlation method used to calculate the persistence length (ξ) plots ln 〈cos θ〉 as a function of arc length along tropomyosin (where θ is the deviation angle from a straight rod); the inverse slope of the regression line yields 2ξ. Persistence length measurements of (a) cardiac and (b) smooth muscle tropomyosin; (♦) plots for 25 nm distal end (labeled ends) sections of tropomyosin; (x) plots for 25 nm central (labeled middle) sections of tropomyosin. Regression lines through the respective points are represented by tick marks. The tangent angles determined for the arc lengths measured were normally distributed.

Our data indicate that the overlap region of cardiac tropomyosin, which includes the end-to-end joint, is relatively flexible unless it is supported by TnT, whereas this region in smooth muscle tropomyosin is comparatively rigid. Examining differences in the bending angle, θ, over the respective 25 nm arc lengths of each distal or central dimer segment (20,21) offers an alternative approach to assess relative flexibility. The set of θ angles calculated either from the persistence length values or by direct measurement (Table 2) indicates that on average, the central end-to-end linked region of the cardiac dimers bends more than any of the other zones tested and therefore is likely to be the most flexible.

Reliability of persistence length data

As a means of determining tropomyosin flexibility, we calculate the persistence length values to quantify the bending variance of tropomyosin. However, measurement error, such as in determining the centerline of tropomyosin molecules during skeletonization, can introduce an extra variance that is unrelated to tropomyosin bending and its persistence length. The inherent variation in tropomyosin bending, however, appears to greatly outweigh the variance due to experimental error. In fact, the persistence length values determined from cardiac tropomyosin monomers preserved by two different techniques (rotary shadowing and negative staining) are virtually the same (102 and 104 nm), and thus methodological error is unlikely. Moreover, when images of tropomyosin are sorted into half data sets (e.g., represented by randomly chosen 25 nm stretches at opposite ends of tropomyosin dimers), comparable persistence length values for each half data set are obtained (110 nm and 106 nm for cardiac, 101 nm and 109 nm for smooth muscle), again suggesting that the measurement errors are small. Lastly, the MD simulation of smooth muscle tropomyosin performed here (and of cardiac tropomyosin performed previously (20)), which is not subject to experimental errors encountered with isolated proteins, provides a completely independent means of characterizing the flexural movement of tropomyosin monomers. Conspicuously, MD conformers of smooth muscle tropomyosin display a persistence length (104 nm) that is the same as values reported above and those in the MD characterization of cardiac tropomyosin (101 nm (20,21)).

Conclusions

Monomeric tropomyosin binds to actin filaments with exceedingly low affinity (16,17). The protein only binds actin effectively as a member of narrow polymeric filaments once the protein self-associates end-to-end. The collective electrostatic interactions between tropomyosin filaments and the surface of actin are then appreciable (16). Thus, thin filaments can be best thought of as a composite structure consisting of semiautonomous actin and tropomyosin filaments, though each component filament is further subject to the influence of troponin, myosin, and other actin-binding proteins. It is therefore not surprising that altered tropomyosin molecules that are incapable of forming end-to-end links cannot associate appreciably with F-actin (30–34). However, once assembled, the tropomyosin filament must be rigid enough to act as a gatekeeper on the thin filaments, thereby governing the access of actin-binding proteins. In contrast, if tropomyosin were very flexible, the gatekeeping function would fail, since actin-binding proteins would inappropriately displace the tropomyosin. Considerable tropomyosin stiffness is also necessary to ensure the effective cooperative movement of tropomyosin over actin in response to myosin cross-bridge binding. Alternatively, if tropomyosin were very flexible, cooperativity would be dampened. In fact, as shown here and in previous studies (20,21), the coiled-coil of tropomyosin is semi-rigid, with an overall apparent persistence length of ∼100 nm.

The ∼100 nm apparent persistence length values measured actually underestimate the rigidity of cardiac tropomyosin monomers by a factor of 4–5, since the inherent curvature of the tropomyosin (comprising the so-called intrinsic persistence length) must be taken into account to determine the dynamic persistence length, a truer measure of flexural rigidity (20,21). MD simulations of tropomyosin offer a means of separating the components of persistence length (20,21) and identifying the dynamic component. An analysis of conformers of smooth muscle tropomyosin taken during the MD simulations performed here shows a trend identical to that found previously for cardiac tropomyosin, i.e., a 104 nm apparent persistence length translates into a 343 nm dynamic persistence length. Hence, EM and MD show that the parameters that describe the flexural stiffness along the coiled-coil structure of both smooth and cardiac tropomyosin are essentially the same.

Although previous studies have shown that isolated tropomyosin molecules behave like semi-rigid rods (20,21), little information is available about the mechanics of the end-to-end linkage within tropomyosin polymers. This deficit is unfortunate, since after all, tropomyosin functions on actin as a polymeric filament and not in isolation. Early works in which striated and smooth muscle tropomyosins were characterized by viscometry and analytical ultracentrifugation indicated that smooth muscle tropomyosin may form more stable polymers, resulting in stronger end-to-end interactions compared to those induced by striated muscle isoforms (18,35–37). It should be noted, however, that hydrodynamic tools assess polymerization indirectly, and the corresponding conclusions reached, although compelling, are subject to alternative explanations. For example, the methods do not necessarily distinguish among the effects of tropomyosin chain length, flexibility, and side-to-side interactions. In this study, we examined and compared the polymerization levels and end-to-end stiffness of smooth and cardiac muscle tropomyosin directly. Indeed, our EM results show a higher propensity of the smooth muscle tropomyosin to polymerize, confirming the earlier inferences. This raises the interesting possibility that preformed smooth muscle (and perhaps nonmuscle) tropomyosin polymers may provide a scaffold for F-actin polymerization and assembly in vivo. Accordingly, in some cases, tropomyosin may serve as a nucleation factor for new actin filament formation. Given the abundance of tropomyosin isoforms in cells, such tropomyosin polymers may be responsible for localizing the assembly of actin filaments in specific cytoskeletal compartments, as proposed by the Gunning group (1,2).

Our evaluation of persistence lengths indicates that the rigidity of smooth muscle tropomyosin is undiminished over their end-to-end linkages, and thus smooth muscle tropomyosin appears to be capable of acting as continuous semi-rigid strands despite the lack of troponin. In marked contrast, striated muscle tropomyosin is relatively flexible over its end-to-end linkage, but in vivo is likely to be strengthened mechanically by troponin, consistent with results reported here for the effect of TnT1 on cardiac tropomyosin. Considerable sequence variation occurs at the C-terminal ends of the respective isoforms (18,36), which may account for different end-to-end interactions and associations with other ligands (38). To gain an explicit understanding of the mechanical and functional differences between tropomyosin isoforms, it is necessary to relate the high-resolution structures of end-to-end tropomyosin junctions to each other.

Our goal is to develop definitive structural models of tropomyosin's regulatory movements on actin to determine the basis of the thin filament's cooperative unit size and behavior. We have shown here that tropomyosin monomers and polymerized tropomyosin strands have quite stiff material properties, consistent with their cooperative behavior on actin. However, a full description of the energy landscape between tropomyosin and actin that constrains the movement of semi-rigid tropomyosin on F-actin is still lacking. Hence, the effective persistence length of tropomyosin on thin filaments, and the influence of myosin and (in the case of striated muscle) troponin on cooperative movement cannot be meaningfully modeled based on the data collected here. The effects of caldesmon on stiffening of tropomyosin in smooth muscle thin filaments, and the influence of calcium on the stiffening effect of troponin in striated muscle thin filaments, as observed here in the absence of actin, also remain to be determined. Thus, despite work by others suggesting tissue-specific differences in thin-filament cooperative unit size in intact systems (39,40), it is premature to speculate about the corresponding underpinnings of tropomyosin's structural dynamics on thin filaments, however stiff the tropomyosin strands are, without an adequate representation of the interface between the two proteins. Although considerable accomplishments in elucidating the structural mechanics of tropomyosins have been achieved, the challenge remains to develop and characterize atomic models of F-actin tropomyosin.

Acknowledgments

Note added in proof: The persistence lengths derived from molecular dynamics simulations of chicken gizzard tropomyosin were mistakenly reported for the αα-isoform and not the αβ-isoform as intended; the values for the two are virtually the same. The apparent persistence length values of αβ-gizzard tropomyosin range between 110 and 120 nm during a 15 ns simulation.

We thank Ms. Jasmine Nirody and Mr. Pingcheng (Jason) Li for their help in skeletonizing the EM images and carrying out preliminary persistence length calculations.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL86655 and HL36153 to W.L., and HL38834 and HL63774 to L.S.T. D.S. was supported by an NIH training grant (HL007224) to the Whitaker Cardiovascular Institute at Boston University (J. E. Freedman, P.I.), and A.C. was supported by NIH grant AR55958 to S. I. Bernstein, San Diego State University. The electron microscope facilities used in this work were supported by NIH grant RR08426 to Roger Craig, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

References

- 1.Gunning P.W., Schevzov G., Hardeman E.C. Tropomyosin isoforms: divining rods for actin cytoskeleton function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunning P.W., O'Neill G., Hardeman E. Tropomyosin-based regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in time and space. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1–35. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry S.V. What is the role of tropomyosin in the regulation of muscle contraction? J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2001;24:593–596. doi: 10.1023/b:jure.0000009811.95652.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J.H., Cohen C. Regulation of muscle contraction by tropomyosin and troponin: how structure illuminates function. Adv. Protein Chem. 2005;71:121–159. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)71004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hitchcock-DeGregori S.E. Tropomyosin: function follows form. Tropomyosin and the steric mechanism of muscle regulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;644:60–72. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-85766-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isambert H., Venier P., Carlier M.F. Flexibility of actin filaments derived from thermal fluctuations. Effect of bound nucleotide, phalloidin, and muscle regulatory proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11437–11444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg M.J., Wang C.-L., Moore J.R. Modulation of actin mechanics by caldesmon and tropomyosin. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:156–164. doi: 10.1002/cm.20251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haselgrove J.C. X-ray evidence for a conformational change in actin-containing filaments of vertebrate striated muscle. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1972;37:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huxley H.E. Structural changes in actin- and myosin-containing filaments during contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1972;37:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parry D.A.D., Squire J.M. Structural role of tropomyosin in muscle regulation: analysis of the x-ray diffraction patterns from relaxed and contracting muscles. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;75:33–55. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehman W., Craig R., Vibert P. Ca2+-induced tropomyosin movement in Limulus thin filaments revealed by three-dimensional reconstruction. Nature. 1994;368:65–67. doi: 10.1038/368065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vibert P., Craig R., Lehman W. Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;266:8–14. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehrer S.S., Morris E.P. Dual effects of tropomyosin and troponin-tropomyosin on actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:8073–8080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehrer S.S., Morris E.P. Comparison of the effects of smooth and skeletal tropomyosin on skeletal actomyosin subfragment 1 ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:2070–2072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamm K.E., Stull J.T. The function of myosin and myosin light chain kinase phosphorylation in smooth muscle. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1985;25:593–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.003113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes K.C., Lehman W. Gestalt-binding of tropomyosin to actin filaments. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2008;29:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s10974-008-9157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tobacman L.S. Thin filament-mediated regulation of cardiac contraction. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1996;58:447–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smillie L.B. Tropomyosin. In: Bárány M., editor. Biochemistry of Smooth Muscle Contraction. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehman W., Galińska-Rakoczy A., Craig R. Structural basis for the activation of muscle contraction by troponin and tropomyosin. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;388:673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li X.E., Holmes K.C., Fischer S. The shape and flexibility of tropomyosin coiled coils: implications for actin filament assembly and regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;395:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X.E., Lehman W., Fischer S. The relationship between curvature, flexibility and persistence length in the tropomyosin coiled-coil. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;170:313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobacman L.S., Adelstein R.S. Mechanism of regulation of cardiac actin-myosin subfragment 1 by troponin-tropomyosin. Biochemistry. 1986;25:798–802. doi: 10.1021/bi00352a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jancsó A., Graceffa P. Smooth muscle tropomyosin coiled-coil dimers. Subunit composition, assembly, and end-to-end interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:5891–5897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shotton D.M., Burke B.E., Branton D. The molecular structure of human erythrocyte spectrin. Biophysical and electron microscopic studies. J. Mol. Biol. 1979;131:303–329. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyler J.M., Branton D. Rotary shadowing of extended molecules dried from glycerol. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1980;71:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(80)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler W.E., Aebi U. Preparation of single molecules and supramolecular complexes for high-resolution metal shadowing. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1983;83:319–334. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(83)90139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flicker P.F., Phillips G.N., Jr., Cohen C. Troponin and its interactions with tropomyosin. An electron microscope study. J. Mol. Biol. 1982;162:495–501. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willison J.H.M., Rowe A.J. Replica, shadowing, and freeze-etching techniques. In: Glauert A.M., editor. Practical Methods in Electron Microscopy. Elsevier/North Holland; Amsterdam: 1980. pp. 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., 3rd, Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson P., Smillie L.B. Polymerizability of rabbit skeletal tropomyosin: effects of enzymic and chemical modifications. Biochemistry. 1977;16:2264–2269. doi: 10.1021/bi00629a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hitchcock-DeGregori S.E., Heald R.W. Altered actin and troponin binding of amino-terminal variants of chicken striated muscle α-tropomyosin expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:9730–9735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heald R.W., Hitchcock-DeGregori S.E. The structure of the amino terminus of tropomyosin is critical for binding to actin in the absence and presence of troponin. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:5254–5259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho Y.J., Liu J., Hitchcock-DeGregori S.E. The amino terminus of muscle tropomyosin is a major determinant for function. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:538–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monteiro P.B., Lataro R.C., Reinach Fde. C. Functional α-tropomyosin produced in Escherichia coli. A dipeptide extension can substitute the amino-terminal acetyl group. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:10461–10466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders C., Smillie L.B. Chicken gizzard tropomyosin: head-to-tail assembly and interaction with F-actin and troponin. Can. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1984;62:443–448. doi: 10.1139/o84-060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nowak E., Dabrowska R. Properties of carboxypeptidase A-treated chicken gizzard tropomyosin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;829:335–341. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(85)90241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graceffa P. In-register homodimers of smooth muscle tropomyosin. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1282–1287. doi: 10.1021/bi00429a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenfield N.J., Kotlyanskaya L., Hitchcock-DeGregori S.E. Structure of the N terminus of a nonmuscle α-tropomyosin in complex with the C terminus: implications for actin binding. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1272–1283. doi: 10.1021/bi801861k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regnier M., Rivera A.J., Gordon A.M. Thin filament near-neighbour regulatory unit interactions affect rabbit skeletal muscle steady-state force-Ca(2+) relations. J. Physiol. 2002;540:485–497. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillis T.E., Martyn D.A., Regnier M. Investigation of thin filament near-neighbour regulatory unit interactions during force development in skinned cardiac and skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007;580:561–576. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hinkle A., Goranson A., Tobacman L.S. Roles for the troponin tail domain in thin filament assembly and regulation. A deletional study of cardiac troponin T. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7157–7164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]