Abstract

Over the last decade, in silico models of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I pathway have developed significantly. Before, peptide binding could only be reliably modelled for a few major human or mouse histocompatibility molecules; now, high-accuracy predictions are available for any human leucocyte antigen (HLA) -A or -B molecule with known protein sequence. Furthermore, peptide binding to MHC molecules from several non-human primates, mouse strains and other mammals can now be predicted. In this review, a number of different prediction methods are briefly explained, highlighting the most useful and historically important. Selected case stories, where these ‘reverse immunology’ systems have been used in actual epitope discovery, are briefly reviewed. We conclude that this new generation of epitope discovery systems has become a highly efficient tool for epitope discovery, and recommend that the less accurate prediction systems of the past be abandoned, as these are obsolete.

Keywords: cytotoxic T lymphocytes, epitope prediction, human leucocyte antigen, major histocompatibility complex class I, major histocompatibility complex–peptide binding

Background

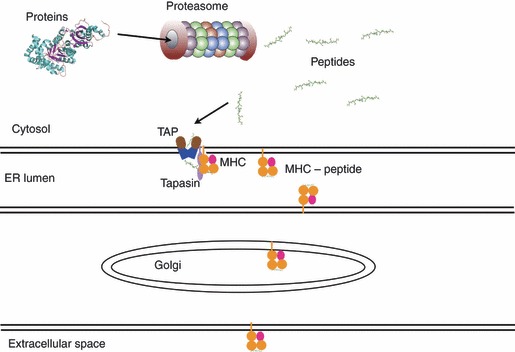

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are the effector cells of the adaptive immune response that deal with infected, or malfunctioning, cells. Whereas intracellular pathogens are shielded from antibodies, CTLs are endowed with the ability to recognize and destroy cells harbouring intracellular threats. This obviously requires that information on the intracellular protein metabolism (including that of any intracellular pathogen) be translocated to the outside of the cell, where the CTL reside. To this end, the immune system has created an elaborate system of antigen processing and presentation. During the initial phase of antigen processing, peptide antigens are generated from intracellular pathogens and translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum. In here, these peptide antigens are specifically sampled by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and then exported to the cell surface, where they are presented as stable peptide: MHC I complexes awaiting the arrival of scrutinizing T cells. Hence, identifying which peptides are able to induce CTLs is of general interest for our understanding of the immune system, and of particular interest for the development of vaccines and immunotherapy directed against infectious pathogens, as previously reviewed.1,2 Peptide binding to MHC molecules is the key feature in cell-mediated immunity, because it is the peptide–MHC class I complex that can be recognized by the T-cell receptor (TCR) and thereby initiate the immune response. The CTLs are CD8+ T cells, whose TCRs recognize foreign peptides in complex with MHC class I molecules. In addition to peptide binding to MHC molecules, several other events have to be considered to be able to explain why a given peptide is eventually presented at the cell surface. Generally, an immunogenic peptide is generated from proteins expressed within the presenting cell, and peptides originating from proteins with high expression rate will normally have a higher chance of being immunogenic, compared with peptides from proteins with a lower expression rate.3 There are, however, significant exceptions to this generalization, e.g. cross-presentation,4–6 but this will be ignored in the following. In the classical MHC class I presenting pathway7–10 (Fig. 1) proteins expressed within a cell will be degraded in the cytosol by the protease complex, named the proteasome.11–13 The proteasome digests polypeptides into smaller peptides 5–25 amino acids in length and is the major protease responsible for generating peptide C termini. Some of the peptides that survive further degradation by other cytosolic exopeptidases can be bound by the transporter associated with antigen presentation (TAP), reviewed by Schölz et al.14 This transporter molecule binds peptides of lengths 9–20 amino acids and transports the peptides into the endoplasmic reticulum, where partially folded MHC molecules [in humans called human leucocyte antigens (HLA)], will complete folding if the peptide is able to bind to the particular allelic MHC molecule. The latter step is furthermore facilitated by the endoplasmic-reticulum-hosted protein tapasin.15,16 Each of these steps has been characterized and their individual importance has been related to final presentation on the cell surface.7,17,18

Figure 1.

Schematic and highly simplified view of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I presenting pathway.ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TAP, transporter associated with antigen presentation.

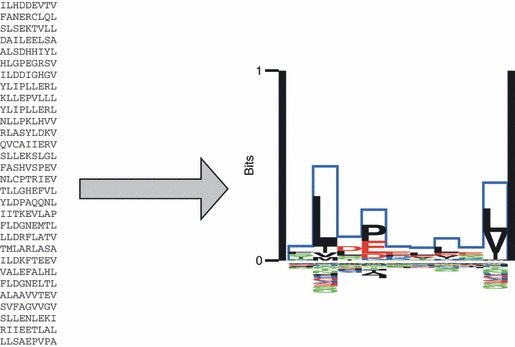

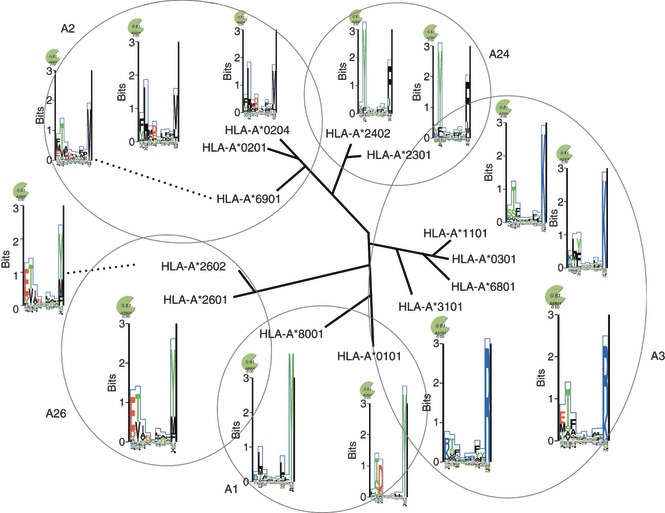

The MHC binding is clearly the most selective part of this pathway and this is one of the reasons why it is of particular interest to describe the MHC–peptide binding system. Another issue is that the information contained in the amino acid sequence regarding the outcome of the biochemical interaction is much stronger for the MHC–peptide binding event than for the proteasomal cleavage and TAP binding and can therefore be modelled more accurately.21 If several different ligands have been identified, it is possible to deduce a binding motif for the given MHC molecule (Fig. 2).22 However, because MHCs in most organisms are highly polymorphic (> 2300 HLA-A and -B alleles have been registered by hla.alleles.org (http://hla.alleles.org/nomenclature/stats.html) and most of the polymorphisms influence the peptide binding specificity, it would be an immense task to describe the binding capabilities of each allelic HLA molecule. This problem has partly been solved by the finding that most HLA molecules share some ligands with other HLA molecules.23 It is possible to group several HLA molecules with similar binding motifs into so called supertypes (Fig. 3),23 and several ways of categorizing the supertypes have been proposed.23–30 This concept clearly has its limitations, though, as one MHC molecule can bind a substantial number of peptides not bound by another member of the same HLA supertype.31 Furthermore, many alleles will not clearly belong to a specific supertype.28,29

Figure 2.

The Kullback–Leibler (KL) sequence logo for the HLA-A*0201 allele is taken from the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) motif viewer website.19 The logo is calculated from the 30 peptides shown in the left panel. The KL information content is plotted along the 9mer. Amino acids with positive influence on the binding are plotted on the positive y-axis, and amino acids with a negative influence on binding are plotted on the negative y-axis. The height of each amino acid is given by their relative contribution to the binding specificity. For details on how to calculate position-specific scoring matrices and sequence logos to characterize binding motif specificities see refs 19,20.

Figure 3.

Schematic view of the relationships between the peptide binding space of some human leucocyte antigen-A alleles clustered into supertypes using information from Lund et al.26 The distances and branch points are artificial and solely for visualization purposes. Sequence logos generated using the predicted peptide binding space as generated by major histocompatibility complex Motifviewer are shown for each allele.

Ultimately, the goal would be to create theoretical models of the MHC class I presenting pathway which would allow scientists and clinicians to predict the immunogenicity of any protein antigen of interest. Most of the steps in the presenting pathway can be modelled as described in the following text. In particular, the MHC binding step can be very accurately predicted.32 Today MHC binding prediction methods have matured to a level where they can be highly resource-saving tools in epitope discovery. However, some misunderstandings have arisen on the usefulness of these tools. Even though the success rates might seem small (< 10% verified epitopes among a tested set of predicted peptides) the value should rather be seen in the light of how many experiments have been saved if the same number of epitopes should have been discovered using only biological and biochemical assays. This issue will be discussed in the following text. These methods should not be considered as oracle tools delivering the ultimate answer but rather as a convenient way to focus the experimental work on the subset of potential immunogenic peptides that will have the highest probability of success.

Experimental identification of MHC binding peptides, natural ligands and T-cell epitopes

To be able to understand the differences between different prediction systems, it is important to realize that different methods have been trained and evaluated on different types of data. The general test of a peptide being a CTL epitope is to detect the responses of T cells derived from individuals having a known immune response against either the full pathogen, or the natural antigen hosting the given peptide. The CTL response can be detected in more or less specific assays as interferon-γ EliSpot assays, intracellular cytokine release assays,5051Cr-release assays, or different proliferation assays. For developing prediction methods, these are data that are usually used in the evaluation process, first because of the limited number of these types of data. Second, we do not know whether a peptide, which has been found negative in one individual, could not be positive in another individual. Third, the diversity in the detection method makes these types of data highly noisy. Another detection method is to elute peptides from HLA molecules that have been expressed by appropriate antigen-presenting cells and subsequently identify them, for example using mass spectrometry. These peptides will have passed through the full class I presenting pathway but will not necessarily be immunogenic as not all such presented peptides (natural ligands) will be able to elicit an immune response. For example will all the presented peptides originating from ‘self’ proteins be ignored by CD8+ T cells, as all lymphocytes carrying TCRs that could have recognized self peptide–MHC complexes have been eliminated through negative selection in the thymus.33 Natural ligands have since 1995 been extensively identified and deposited in the publicly available database SYFPEITHI.34,35 These data have been used in both development and validation of prediction systems (see later). The data represent only detected positives, and the remaining peptides that theoretically could be generated from the same source protein can be assumed to be negative (although it should be noted that this is merely an assumption). The above-described types of data are qualitative in nature and referred to as classification or binary data.

Biochemical assays for detecting single steps in the presenting pathway have also been developed, e.g. MHC–peptide binding assays exist in several variants, but have evolved towards higher throughput systems.36–43 MHC–peptide binding strength is usually reported either as the binding affinity, or as an arbitrary score. The different types of data are available from different sources. The most important are listed in Table 1. The newest of these databases, the Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (IEDB)44 contains categorized information from most of the other available databases.

Table 1.

Web accessible databases for major histocompatibility complex-binding and/or epitope data

| Resource | URL |

|---|---|

| AntiJen | http://www.jenner.ac.uk/antijen |

| EPIMHC | http://immunax.dfci.harvard.edu/epimhc/ |

| HCV immunology | http://hcv.lanl.gov |

| HIV immunology | http://www.hiv.lanl.gov |

| IEDB | http://www.immuneepitope.org/ |

| MHCBN | http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/mhcbn |

| SYFPEITHI | http://www.syfpeithi.de |

Prediction algorithms

As the technical background behind the most successful and popular methods has been extensively reviewed,21,45 we will in the following text try to explain more generally the concepts of the most popular and web-accessible methods.

MHC binding prediction methods

Several approaches have been published that predict peptide binding to MHC molecules using known three-dimensional structures. Despite the appealing approach these structure-based models have so far not been able to gain an accuracy that is comparable with the sequence-based methods described below. This is true even regarding MHCs where very few or no examples of binding peptides are available (Zhang et al. 2010, submitted).

The relatively strong sequence signal coupled with the importance of the MHC–peptide binding event has made peptide–MHC binding the preferred target of the development of prediction tools. Together with the identification of the first MHC binding peptides, it became clear that there were some systematic preferences in the amino acid composition and sequence of peptides binding specific MHC molecules, which led to the definition of the first rule and motif-based prediction systems.47–50 The most important method based on qualitative data was the web-accessible prediction system SYFPEITHI34,35 which is still updated and used.

Later the assay systems developed to be able to give quantitative measurements on either KD/EC50 or stability/half-life and with this came the possibility of measuring the affinity of selected synthetic peptides. Interpretations of these experiments were often based upon the assumption that the single amino acid at each position in the peptide contributes equally to the total affinity of the given peptide. The prediction system BIMAS51 was originally created using 156 of such peptides to establish the total peptide binding (i.e. half-life) motif of the human MHC molecule HLA-A*0201 and develop a complete matrix reflecting the importance of each amino acid in each position of the peptide motif. Several HLA molecules were characterized in this way and the corresponding BIMAS prediction system is accessible through the web and remains highly used. A particularly powerful way to obtain the above-mentioned matrix involved the use of full or partial positional scanning combinatorial peptide libraries (PSCPL).52,53 As the amount of reliable binding data has increased, complex machine learning methods have also been developed. These methods range from statistically modified motif systems such as position-specific scoring matrices,54–56 Hidden Markov Models,57 through more sophisticated scoring matrix-generating methods using quantitative data51–60 to machine learning systems with the capacity to capture the potential influence of the sequence context on the binding contribution of a given amino acid in the binding peptide such as artificial neural networks (ANN)61–63 and support vector machines (SVM).64–67 A large number of peptide binding data generated by biochemical assays have been deposited in the IEDB database, and have, as a consequence, been included in training several of the newer MHC class I peptide binding predictors, e.g. stabilized matrix method (SMM)59 and NetMHC,63,68 which are both included as tools in IEDB and have been ranked as the best performing in separate benchmarks.32,69

As the majority of HLA class I molecules have a preference for peptides of length 9 amino acids, the majority of binding affinities have been measured using 9mer peptides. For this reason, it has been difficult to develop reliable prediction systems for lengths other than 9, which is certainly needed because a significant part of the binding peptides have lengths of 8, 10 and 11 amino acids, and some are even longer. However, prediction systems trained on 9mer data can actually be used to fairly accurately predict the binding affinities of 8-, 10-, and 11mer peptides.80 This method is used in the web-accessible version of NetMHC-3.0.68

As described in the introduction, MHC alleles can be clustered into supertypes because many allelic molecules have overlapping peptide specificities (Fig. 3). 23,27–30 However, the binding similarities between alleles are not always obvious from the sequence similarity, as some alleles with very similar HLA sequences will have different binding motifs and vice versa.31–73 From this follows naturally the question if it will be possible to have prediction systems for all the alleles needed to cover any human subpopulation, and all the relevant MHC class I alleles for important model organisms (e.g. mice, rats, ferrets, monkeys). Because of lack of data, it is possible to make allele-specific predictions for fewer than 100 of the more than 2000 known HLA-A and -B alleles. However, more general systems have been developed that are in fact able to generalize to allelic molecules with otherwise unknown binding specificity (i.e. no or few examples of binding peptides are known).73–78 This type of predictor is, in the following text, referred to as being pan-specific. In the only benchmark performed so far, NetMHCpan was validated as the best of the methods compared,79 and a recent update of this method is able to accurately predict peptide binding even for MHCs from several non-human mammals.73 The accuracy of such predictions is correlated with the sequence similarity distance to alleles for which peptide binding data exist, and if this distance is large then the best methods are the pocket-derived predictions, such as Modular Peptide Binding77 and PickPocket.78 A list of prediction methods, including those described here, is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

URLs of web-accessible major histocompatibility complex binding predictors

Predictions by the use of integrated systems

The first step in the degradation of internally produced proteins is the digestion of the polypeptide by the protease complex known as the proteasome. The proteasome exists in higher eukaryotes in two forms. One form is named the constitutive or 20s proteasome and is expressed in normally functional cells. The complex consists of several subunits including three different subunits with protease activity. The protease subunits will be replaced with three other subunits with slightly different specificity when the cell is in a state of immune alertness. The final complex carrying these subunits is named the immuno-proteasome. The resulting polypeptides might be further degraded by exopeptidases with N-terminal specificity, but so far no other cytosolic protease activity has been discovered that will change the C termini created by the proteasome.

Peptides generated by the proteasome must be able to bind and be transported into the endoplasmic reticulum by the transmembrane transporter complex TAP. The amount of data regarding TAP binding and transport are even scarcer than is the case for proteasomal digestion data and regards almost exclusively the binding event.

Compared to MHC binding, much less effort has been invested in the modelling of proteasomal and TAP events. However, several methods have been developed and a number of web-accessible prediction systems exist (Table 2). It is possible to model these events to a resolution where meaningful predictions can be obtained regarding each of these events. Incorporation of predictions of TAP binding and proteasomal cleavage with MHC binding predictions to a model of the MHC class I presenting pathway can be a valuable tool in epitope discovery, even though the degree of gain over pure MHC binding predictions have been discussed.80,81 Especially when only a limited number of potential epitopes are to be tested, which is often the case, modelling of the full pathway will give significant improvement over a pure MHC binding prediction. However, for experiments where it is important to detect a high number of epitopes, even if more peptides have to be tested per epitope discovered, the best results are obtained by using MHC binding predictions alone (Stranzl et al. 2010, submitted). A number of integrated models for peptide presentation have been developed, and MHC-pathway,83 NetCTL,84,85 and NetCTLpan (Stranzl et al. 2010, submitted) have been shown to be the most accurate when evaluated both on natural ligands and known T-cell epitopes (Stranzl et al. 2010, submitted).85 NetCTLpan is the only integrated MHC class I pathway modelling method so far to take advantage of pan-specific MHC prediction and therefore be able to model presentations by any HLA allele with known protein sequence. A large-scale benchmark by independent groups has not yet been performed for these integrated systems.

Host and pathogen diversity

Many pathogens have a large genomic diversity between individual entities within the total population. This is a problem when specific epitopes are selected for vaccine or diagnostic purposes, as an epitope from one strain of a given pathogen might not be recognized by individuals immunized with another strain of the same pathogen. This is especially problematic concerning highly mutating viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis C virus, but also influenza A viruses differ significantly and new serotypes arise occasionally. The most straightforward solution is to select highly conserved possible epitopes considering the whole genomic population of a certain pathogen. This solution has been verified to work with influenza A virus,86 and has also been optimized mathematically and built into the automated web-accessible system OptiTope.87,88 However, to only consider conserved epitopes might be highly restraining regarding to the number of final verified epitopes and might also result in entire subpopulations of the pathogen remaining untargeted by the epitope selection, which would be highly undesirable in a vaccine context. Another investigated approach, named the EpiSelect algorithm, has been to select a pool of potential epitopes that together will cover the full diversity of a given population. A solution where potential (predicted) HIV epitopes were selected in an iterative manner – selecting preferably those epitopes hosted in untargeted genomes – has been tried out experimentally with success.85

Regarding diversity on the host side, the issue of MHC being highly polymorphic as discussed earlier, further complicates the identification of broadly immunogenic epitopes. To cover all individuals and populations, epitopes have to be considered that will cover as broad a population as possible. OptiTope87,88 can select a broadly covering pool of peptides using MHC binding predictions for a number of common alleles where the more common alleles will be given a higher consideration. This selection scheme will furthermore also take into consideration how conserved a given peptide is in the pathogen population as described above. However, this approach is not necessarily optimal because many alleles share large parts of their binding specificity, and will hence in their population coverage estimation have a significant overlap of individuals that are possibly already covered by other selected peptides. For this reason the total fraction of covered individuals might be overestimated. The method has so far only been benchmarked using existing public domain data, and direct experimental validations are still to come.

One problem in comparing different epitope discovery methods is that no common benchmark has been accepted and used within the community. As a partial compensation for that, an open international competition was launched in 2009 in ‘Machine Learning in Immunology’ (MLI, http://www.kios.org.cy/ICANN09/MLIProgram.html). This first competition was focused on MHC peptide binding for only three HLA alleles and 9mer and 10mer peptides. The three alleles chosen, HLA-A*0101, HLA-A*0201, and HLA-B*0702, are common in the western population and have been studied extensively. For this reason a fairly large set of measured 9mer binding affinities was available for training and the results therefore favour the methods that could take advantage of this. A comparison of the MLI results for BIMAS and SYFPEITHI with the results for NetMHC-3.2, NetMHCpan-2.2, an average of the latter two, and finally PickPocket are shown in Table 3. We see that the newer methods have a significantly better performance than BIMAS and SYFPEITHI, as measured by area under the curve or Pearson correlation coefficient. Interestingly, even general methods that can also model peptide binding to HLA molecules where very few or no binding peptides are known, such as PickPocket, actually have a comparable or better outcome in this comparison than the older methods. The winners were revealed at the workshop and all participants have received the results from the organizers, but unfortunately the results have not yet been formally published.

Table 3.

Area under a receiver operating characteristic curve values for blind predictions of a set of measured human leucocyte antigen (HLA)–peptide binding affinities

| Method | HLA-A*0101 9mer | HLA-A*0201 9mer | HLA-B*0702 9mer | HLA-A*0101 10mer | HLA-A*0201 10mer | HLA-B*0702 10mer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIMAS | 0·91 | 0·99 | 0·92 | 0·92 | 0·99 | 0·85 |

| SYFPEITHI | 0·92 | 0·98 | 0·72 | 0·69 | 0·96 | 0·82 |

| NetMHC-3.2 | 0·96 | 0·99 | 0·95 | 0·99 | 0·99 | 0·94 |

| NetMHCpan-2.2 | 0·96 | 0·99 | 0·96 | 0·98 | 0·99 | 0·97 |

| NetMHC-ave (a) | 0·96 | 0·99 | 0·96 | 0·99 | 0·99 | 0·95 |

| PickPocket | 0·93 | 0·99 | 0·92 | 0·95 | 0·98 | 0·91 |

The performances of different prediction methods are given for prediction and binding to each of the three alleles, HLA-A*0101, HLA-A*0201, and HLA-B*0702, for two peptide set consisting of 9- and 10mer peptides, respectively.

The use of in silico methods in experimental epitope discovery

There has been some dispute regarding the usefulness of epitope predictions in general and MHC binding predictions in particular in the context of epitope discovery. One particular paper did find that binding predictions were not correlated to actual peptide binding and concluded that such binding predictions were of limited interest.90 This paper was, however, flawed by comparing a less-than-optimal prediction method with data generated using a method that is, at best, semi-quantitative.91 Nonetheless, this flawed comparison is still taken into account by some when discussing the value of prediction methods.92 In reality, later and more comprehensive validations using data from several different binding assays have firmly established that modern binding predictions are accurate and of high value in reducing the cost for epitope discovery,32,69 as will be discussed below.

The value of binding predictions for epitope discovery has been clearly shown in the work of Moutaftsi et al.,93 in which a consensus binding prediction using the BIMAS,51 PSCPL-derived matrices,53 Average Relative Binding (ARB)58 and SMM59,60 methods were used to find the majority of the CTL response in vaccinia-challenged mice, examining only 1% of the potential 9- and 10mer peptides. The significance of this work has been discussed elsewhere.94 Furthermore, when used to identify MHC binders for a particular pathogen (e.g. severe acute respiratory syndrome) these methods have a hit rate of more than 90% validated binders for several alleles.36 Below we will go through some recent published works in which different aspects of in silico methods have proved to be an advantage in experimental epitope discovery regarding different types of infectious pathogens.

In an attempt to discover highly conserved influenza A virus epitopes, protein sequences from several human H1N1 virus strains were examined for predicted epitopes using NetCTL.86 A fixed number of peptides (15) was to be predicted for a representative allele for each the 12 supertypes defined by Lund et al.,28 i.e. 180 peptides in total. As a consequence of the high variability of influenza A virus, a number of the selected peptides were actually predicted to bind with a weaker affinity than the generally accepted threshold of 500 nm. A total of 167 peptides were tested for binding biochemically and 120 (72%) of these were found to be binding to the MHC molecule in question stronger than the threshold. Thirteen (8%) were verified as actual CTL epitopes, 11 of these were 100% conserved in H5N1 bird flu virus strains82, and all 13 were 100% conserved in the new 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus strain of swine origin (Ole Lund, unpublished data).

In the above experiment, highly conserved peptides were selected, but for highly mutating viruses such as HIV there would not have been any totally conserved predicted epitopes, so instead it was attempted for each supertype to use the EpiSelect algorithm to create a pool of peptides where one or more of the peptides would be hosted in any HIV isolate.89 One hundred and eighty-five NetCTL predicted peptides were tested against blood from a cohort of 31 HIV-infected patients with different ethnicity infected with different subtypes. It was found that 30 of the 31 patients had responses against at least one peptide and 116 of the 185 peptides (62%) induced a response in at least one patient. Twenty-one of the recognized peptides induced a response in more than four patients (13% of the study subjects). In this case the modelling of the MHC class I pathway combined with an appropriate theoretical selection scheme turned out to be successful.

In the previous described experiments full genomes were searched for potential CTL epitopes, but even in less exhaustive searches the use of predictive models has been beneficial. In a search for CTL epitopes in the E7 antigen of human papillomavirus type 1195 BIMAS HLA-A*0201 predictions were combined with a test for optimal anchor positions.96,97 Only five peptides were synthesized and tested for CTL reactivity, but one of these was identified as a CTL epitope.

Even though peptides have to be able to bind to an MHC class I molecule with a certain strength to able to elicit a CTL response, no definite experiments have shown a good correlation between MHC binding peptide affinity and the immunogenicity beyond this criteria for binding. However, very old (> 30 years) vaccine-induced vaccinia responses were detected with only a small part of the predicted epitopes, and only very strongly binding peptides (Kd < 5 nm) were found to recall a response.98 Peptides were selected to be conserved within the full genome of seven related orthopox strains, including vaccinia, cowpox, and variola major viruses. Then the NetCTL method was used to identify potentially immunogenic peptides restricted to allele representatives for each of 12 supertypes.28 A total of 177 peptides were synthesized and tested in a biochemical in vitro binding assay and 139 peptides (79%) bound to their respective HLA molecules with a Kd < 500 nm. One hundred and five peptides were tested for immunogenicity and eight (8%) of these were positive but all had a measured Kd < 5 nm, so in this case a very strong correspondence between affinity and reactivity was observed.

Most experimental searches described here were performed with viruses, even though the orthopox family is actually a large and complex pathogen. However, recently, the genome of the parasite Leishmania major was mined with respect to class I epitopes.99 Consensus epitope predictions from 8272 annotated protein sequences restricted to the mouse alleles H-2Dd and H-2Kd were performed using five to eight different algorithms. The prediction algorithms included among others SYFPEITHI, BIMAS, ANNPred100,101 and SVMHC.64 No binding assays were performed, but of 78 potential class I CD8 epitopes 26 were tested for their ability to be immunogenic when mice were challenged. Fourteen (54%) of the peptides turned out to be immunogenic.

Discussion

In the previous text a number of methods and applications have been described and we have argued that at present MHC class I in silico models can significantly reduce the effort needed to conduct an epitope discovery experiment. Especially for purposes were just a few epitopes need to be identified these tools are of significant value. Already high throughput experimental assays for detection of MHC–peptide binding strengths are integrated into semi-automatic systems for epitope discovery in pathogens with larger genomes, as bacterial or parasitic organisms. However, there is no doubt that human interpretation by experienced immunologists is needed to correctly validate the outcome of such prediction systems and the most fruitful work seems to be made in close collaborative efforts between immunologists, biochemists and bioinformaticians. As described in the previous sections, prediction systems such as SYFPEITHI and BIMAS, which for many years were state of the art, have now been significantly outcompeted by the newer methods, both regarding accuracy on peptide binding classification and for identifying immunogenic peptides. However, these methods are still widely used even though changing to more recent methods could save a significant amount of resources.

One way to further develop, promote and gain confidence in the newer methods will undoubtedly be to expand the MLI competition. Ideally it should include both well-studied as well as previously unstudied alleles, and include not only binding, but also identification of immunogens.

References

- 1.Purcell AW, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. More than one reason to rethink the use of peptides in vaccine design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:404–14. doi: 10.1038/nrd2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivona S, Gardy JL, Ramachandran S, Brinkman FS, Raghava GP, Flower DR, Filippini F. Computer-aided biotechnology: from immuno-informatics to reverse vaccinology. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juncker AS, Larsen MV, Weinhold N, Nielsen M, Brunak S, Lund O. Systematic characterisation of cellular localisation and expression profiles of proteins containing MHC ligands. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8α+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung S, Unutmaz D, Wong P, et al. In vivo depletion of CD11c+ dendritic cells abrogates priming of CD8+ T cells by exogenous cell-associated antigens. Immunity. 2002;17:211–20. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segura E, Albiston AL, Wicks IP, Chai SY, Villadangos JA. Different cross-presentation pathways in steady-state and inflammatory dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20377–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910295106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen PE. Recent advances in antigen processing and presentation. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1041–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloetzel PM. Generation of major histocompatibility complex class I antigens: functional interplay between proteasomes and TPPII. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:661–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schölz C, Tampé R. The peptide-loading complex – antigen translocation and MHC class I loading. Biol Chem. 2009;390:783–94. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raghavan M, Del Cid N, Rizvi SM, Peters LR. MHC class I assembly: out and about. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sollner S, Macheroux P. New roles of flavoproteins in molecular cell biology: an unexpected role for quinone reductases as regulators of proteasomal degradation. FEBS J. 2009;276:4313–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marques AJ, Palanimurugan R, Matias AC, Ramos PC, Dohmen RJ. Catalytic mechanism and assembly of the proteasome. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1509–36. doi: 10.1021/cr8004857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schölz C, Tampé R. The intracellular antigen transport machinery TAP in adaptive immunity and virus escape mechanisms. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:509–15. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonhardt RM, Keusekotten K, Bekpen C, Knittler MR. Critical role for the tapasin-docking site of TAP2 in the functional integrity of the MHC class I-peptide-loading complex. J Immunol. 2005;175:5104–5114. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehner PJ, Surman MJ, Cresswell P. Soluble tapasin restores MHC class I expression and function in the tapasin-negative cell line .220. Immunity. 1998;8:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kloetzel PM. The proteasome and MHC class I antigen processing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapin N, Hoof I, Lund O, Nielsen M. The MHC motif viewer: a visualization tool for MHC binding motifs. Curr Protoc Immunol 2010. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1817s88. Chapter 18, Unit 18.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapin N, Kesmir C, Frankild S, Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Brunak S, Lund O. Modelling the human immune system by combining bioinformatics and systems biology approaches. J Biol Phys. 2006;32:335–53. doi: 10.1007/s10867-006-9019-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundegaard C, Lund O, Kesmir C, Brunak S, Nielsen M. Modeling the adaptive immune system: predictions and simulations. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3265–75. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buus S, Sette A, Colon SM, Miles C, Grey HM. The relation between major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction and the capacity of Ia to bind immunogenic peptides. Science. 1987;235:1353–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2435001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidney J, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, et al. Several HLA alleles share overlapping peptide specificities. J Immunol. 1995;154:247–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan P, Doytchinova IA, Flower DR. The classification of HLA supertypes by GRID/CPCA and hierarchical clustering methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;409:143–54. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-118-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reche PA, Reinherz EL. Definition of MHC supertypes through clustering of MHC peptide-binding repertoires. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;409:163–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-118-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doytchinova IA, Guan P, Flower DR. Identifiying human MHC supertypes using bioinformatic methods. J Immunol. 2004;172:4314–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hertz T, Yanover C. Identifying HLA supertypes by learning distance functions. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:e148–55. doi: 10.1093/Bioinformatics/btl324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lund O, Nielsen M, Kesmir C, et al. Definition of supertypes for HLA molecules using clustering of specificity matrices. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:797–810. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sidney J, Peters B, Frahm N, Brander C, Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1471–2172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reche PA, Reinherz EL. Artificial Immune Systems, Proceedings. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2004. Definition of MHC supertypes through clustering of MHC peptide binding repertoires; pp. 189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hillen N, Mester G, Lemmel C, et al. Essential differences in ligand presentation and T cell epitope recognition among HLA molecules of the HLA-B44 supertype. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2993–3003. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters B, Bui HH, Frankild S, et al. A community resource benchmarking predictions of peptide binding to MHC-I molecules. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudolph MG, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. How TCRs bind MHCs, peptides, and coreceptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:419–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rammensee H, Bachmann J, Emmerich NP, Bachor OA, Stevanovic S. SYFPEITHI: database for MHC ligands and peptide motifs. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:213–9. doi: 10.1007/s002510050595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rammensee HG, Friede T, Stevanoviíc S. MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics. 1995;41:178–228. doi: 10.1007/BF00172063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sylvester-Hvid C, Kristensen N, Blicher T, et al. Establishment of a quantitative ELISA capable of determining peptide-MHC class I interaction. Tissue Antigens. 2002;59:251–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.590402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harndahl M, Justesen S, Lamberth K, Røder G, Nielsen M, Buus S. Peptide binding to HLA class I molecules: homogenous, high-throughput screening, and affinity assays. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:173–80. doi: 10.1177/1087057108329453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buus S, Stryhn A, Winther K, Kirkby N, Pedersen LO. Receptor–ligand interactions measured by an improved spun column chromatography technique. A high efficiency and high throughput size separation method. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1243:453–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)00172-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khilko SN, Corr M, Boyd LF, Lees A, Inman JK, Margulies DH. Direct detection of major histocompatibility complex class I binding to antigenic peptides using surface plasmon resonance. Peptide immobilization and characterization of binding specificity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15425–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wulf M, Hoehn P, Trinder P. Identification of human MHC class I binding peptides using the iTOPIA-epitope discovery system. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;524:361–7. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-450-6_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Townsend A, Elliott T, Cerundolo V, Foster L, Barber B, Tse A. Assembly of MHC class I molecules analyzed in vitro. Cell. 1990;62:285–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90366-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Townsend A, Ohlén C, Bastin J, Ljunggren HG, Foster L, Kärre K. Pillars article: association of class I major histocompatibility heavy and light chains induced by viral peptides. Nature 1989. 340: 443–448. J Immunol. 2007;179:4301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Olsen AC, Pedersen LO, Hansen AS, Nissen MH, Olsen M, Hansen PR, Holm A, Buus S. A quantitative assay to measure the interaction between immunogenic peptides and purified class I major histocompatibility complex molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:385–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters B, Sidney J, Bourne P, et al. The immune epitope database and analysis resource: from vision to blueprint. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lafuente EM, Reche PA. Prediction of MHC–peptide binding: a systematic and comprehensive overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:3209–20. doi: 10.2174/138161209789105162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Wang P, Papangelopoulos N, et al. Limitations of Ab initio predictions of peptide binding to MHC class II molecules. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falk K, Rotzschke O, Rammensee HG. Cellular peptide composition governed by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 1990;348:248–51. doi: 10.1038/348248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Stevanović S, Jung G, Rammensee HG. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature. 1991;351:290–6. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sette A, Buus S, Appella E, Smith JA, Chesnut R, Miles C, Colon SM, Grey HM. Prediction of major histocompatibility complex binding regions of protein antigens by sequence pattern analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3296–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claverie JM, Kourilsky P, Langlade-Demoyen P, Chalufour-Prochnicka A, Dadaglio G, Tekaia F, Plata F, Bougueleret L. T-immunogenic peptides are constituted of rare sequence patterns. Use in the identification of T epitopes in the human immunodeficiency virus gag protein. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1547–53. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J Immunol. 1994;152:163–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stryhn A, Pedersen LO, Romme T, Holm CB, Holm A, Buus S. Peptide binding specificity of major histocompatibility complex class I resolved into an array of apparently independent subspecificities: quantitation by peptide libraries and improved prediction of binding. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1911–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Udaka K, Wiesmüller KH, Kienle S, et al. An automated prediction of MHC class I-binding peptides based on positional scanning with peptide libraries. Immunogenetics. 2000;51:816–28. doi: 10.1007/s002510000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P, Hvid CS, Lamberth K, Buus S, Brunak S, Lund O. Improved prediction of MHC class I and class II epitopes using a novel Gibbs sampling approach. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1388–97. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reche PA, Glutting JP, Reinherz EL. Prediction of MHC class I binding peptides using profile motifs. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:701–9. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lauemøller SL, Holm A, Hilden J, Brunak S, Holst Nissen M, Stryhn A, Østergaard Pedersen L, Buus S. Quantitative predictions of peptide binding to MHC class I molecules using specificity matrices and anchor-stratified calibrations. Tissue Antigens. 2001;57:405–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057005405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mamitsuka H. Predicting peptides that bind to MHC molecules using supervised learning of hidden Markov models. Proteins. 1998;33:460–74. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19981201)33:4<460::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bui HH, Sidney J, Peters B, et al. Automated generation and evaluation of specific MHC binding predictive tools: ARB matrix applications. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:304–14. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0798-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peters B, Sette A. Generating quantitative models describing the sequence specificity of biological processes with the stabilized matrix method. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peters B, Tong WW, Sidney J, Sette A, Weng ZP. Examining the independent binding assumption for binding of peptide epitopes to MHC-1 molecules. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1765–72. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brusic V, Rudy G, Harrison LC. Prediction of MHC binding peptides using artificial neural networks. In: Stonier RJ, Yu XS, editors. Complex Systems: Mechanism of Adaptation. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 1994. pp. 253–60. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buus S, Lauemoller SL, Worning P, et al. Sensitive quantitative predictions of peptide–MHC binding by a ‘Query by Committee’ artificial neural network approach. Tissue Antigens. 2003;62:378–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P, Lauemoller SL, Lamberth K, Buus S, Brunak S, Lund O. Reliable prediction of T-cell epitopes using neural networks with novel sequence representations. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1007–17. doi: 10.1110/ps.0239403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donnes P, Elofsson A. Prediction of MHC class I binding peptides, using SVMHC. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang GL, Bozic I, Kwoh CK, August JT, Brusic V. Prediction of supertype-specific HLA class I binding peptides using support vector machines. J Immunol Methods. 2007;320:143–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao Y, Pinilla C, Valmori D, Martin R, Simon R. Application of support vector machines for T-cell epitopes prediction. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1978. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhasin M, Raghava GP. Prediction of CTL epitopes using QM, SVM and ANN techniques. Vaccine. 2004;22:3195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M. NetMHC-3.0: accurate web accessible predictions of human, mouse and monkey MHC class I affinities for peptides of length 8-11. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W509–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin HH, Ray S, Tongchusak S, Reinherz EL, Brusic V. Evaluation of MHC class I peptide binding prediction servers: applications for vaccine research. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lundegaard C, Lund O, Nielsen M. Accurate approximation method for prediction of class I MHC affinities for peptides of length 8, 10 and 11 using prediction tools trained on 9mers. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1397–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frahm N, Yusim K, Suscovich TJ, et al. Extensive HLA class I allele promiscuity among viral CTL epitopes. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2419–33. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamberth K, Røder G, Harndahl M, Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Schafer-Nielsen C, Lund O, Buus S. The peptide-binding specificity of HLA-A*3001 demonstrates membership of the HLA-A3 supertype. Immunogenetics. 2008;60:633–43. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0317-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoof I, Peters B, Sidney J, Pedersen LE, Sette A, Lund O, Buus S, Nielsen M. NetMHCpan, a method for MHC class I binding prediction beyond humans. Immunogenetics. 2009;61:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0341-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heckerman D, Kadie C, Listgarten J. Leveraging information across HLA alleles/supertypes improves epitope prediction. J Comput Biol. 2007;14:736–46. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2007.R013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacob L, Vert JP. Efficient peptide–MHC-I binding prediction for alleles with few known binders. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:358–366. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Blicher T, et al. NetMHCpan, a method for quantitative predictions of peptide binding to any HLA-A and -B locus protein of known sequence. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DeLuca DS, Khattab B, Blasczyk R. A modular concept of HLA for comprehensive peptide binding prediction. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang H, Lund O, Nielsen M. The PickPocket method for predicting binding specificities for receptors based on receptor pocket similarities: application to MHC–peptide binding. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1293–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang H, Lundegaard C, Nielsen M. Pan-specific MHC class I predictors: a benchmark of HLA class I pan-specific prediction methods. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:83–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Keşmir C. The role of the proteasome in generating cytotoxic T-cell epitopes: insights obtained from improved predictions of proteasomal cleavage. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0781-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peters B, Bulik S, Tampe R, Endert PMV, Holzhutter HG. Identifying MHC class I epitopes by predicting the TAP transport efficiency of epitope precursors. J Immunol. 2003;171:1741–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stranzl T, Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Nielsen M. NetCTLpan: pan-specific MHC class I pathway epitope predictions. Immunogenetics 2010. doi: 10.1007/s00251-010-0441-4. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tenzer S, Peters B, Bulik S, et al. Modeling the MHC class I pathway by combining predictions of proteasomal cleavage, TAP transport and MHC class I binding. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1025–37. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Buus S, Brunak S, Lund O, Nielsen M. An integrative approach to CTL epitope prediction: a combined algorithm integrating MHC class I binding, TAP transport efficiency, and proteasomal cleavage predictions. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2295–303. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M. Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang M, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, et al. CTL epitopes for influenza A including the H5N1 bird flu; genome-, pathogen-, and HLA-wide screening. Vaccine. 2007;25:2823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Toussaint NC, Dönnes P, Kohlbacher O. A mathematical framework for the selection of an optimal set of peptides for epitope-based vaccines. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Toussaint NC, Kohlbacher O. OptiTope – a web server for the selection of an optimal set of peptides for epitope-based vaccines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W617–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Perez CL, Larsen MV, Gustafsson R, et al. Broadly immunogenic HLA class I supertype-restricted elite CTL epitopes recognized in a diverse population infected with different HIV-1 subtypes. J Immunol. 2008;180:5092–100. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Andersen MH, Tan L, Søndergaard I, Zeuthen J, Elliott T, Haurum JS. Poor correspondence between predicted and experimental binding of peptides to class I MHC molecules. Tissue Antigens. 2000;55:519–31. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.550603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elvin J, Potter C, Elliott T, Cerundolo V, Townsend A. A method to quantify binding of unlabeled peptides to class I MHC molecules and detect their allele specificity. J Immunol Methods. 1993;158:161–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gowthaman U, Agrewala JN. In silico methods for predicting T-cell epitopes: Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde? Expert Rev Proteomics. 2009;6:527–37. doi: 10.1586/epr.09.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Moutaftsi M, Peters B, Pasquetto V, Tscharke DC, Sidney J, Bui HH, Grey H, Sette A. A consensus epitope prediction approach identifies the breadth of murine T(CD8+)-cell responses to vaccinia virus. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:817–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lundegaard C, Nielsen M, Lund O. The validity of predicted T-cell epitopes. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:537–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu Y, Zhu KJ, Chen XZ, Zhao KJ, Lu ZM, Cheng H. Mapping of cytotoxic T lymphocytes epitopes in E7 antigen of human papillomavirus type 11. Arch Dermatol Res. 2008;300:235–42. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kast WM, Brandt RM, Sidney J, Drijfhout JW, Kubo RT, Grey HM, Melief CJ, Sette A. Role of HLA-A motifs in identification of potential CTL epitopes in human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 proteins. J Immunol. 1994;152:3904–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ruppert J, Sidney J, Celis E, Kubo RT, Grey HM, Sette A. Prominent role of secondary anchor residues in peptide binding to HLA-A2.1 molecules. Cell. 1993;74:929–37. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tang ST, Wang M, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, Dziegiel MH, Claesson MH, Buus S, Lund O. MHC-I-restricted epitopes conserved among variola and other related orthopoxviruses are recognized by T cells 30 years after vaccination. Arch Virol. 2008;153:1833–44. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0194-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Herrera-Najera C, Piña-Aguilar R, Xacur-Garcia F, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Dumonteil E. Mining the Leishmania genome for novel antigens and vaccine candidates. Proteomics. 2009;9:1293–301. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brusic V, Bajic VB, Petrovsky N. Computational methods for prediction of T-cell epitopes—a framework for modelling, testing, and applications. Methods. 2004;34:436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lin HH, Zhang GL, Tongchusak S, Reinherz EL, Brusic V. Evaluation of MHC-II peptide binding prediction servers: applications for vaccine research. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(Suppl. 12):S22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S12-S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]