Abstract

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is a potent inflammatory cytokine, which is implicated in acute and chronic inflammatory disorders. The activity of IL-1β is regulated by the proteolytic cleavage of its inactive precursor resulting in the mature, bioactive form of the cytokine. Cleavage of the IL-1β precursor is performed by the cysteine protease caspase-1, which is activated within protein complexes termed ‘inflammasomes’. To date, four distinct inflammasomes have been described, based on different core receptors capable of initiating complex formation. Both the host and invading pathogens need to control IL-1β production and this can be achieved by regulating inflammasome activity. However, we have, as yet, little understanding of the mechanisms of this regulation. In particular the negative feedbacks, which are critical for the host to limit collateral damage of the inflammatory response, remain largely unexplored. Recent exciting findings in this field have given us an insight into the potential of this research area in terms of opening up new therapeutic avenues for inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: inflammasomes, interleukin-1β, regulators

Introduction

Over the past 15 years, our understanding of the innate immune system has changed dramatically based on the identification of key receptors. The discovery of toll-like receptors (TLRs) provided the first insights into how innate immune cells distinguish self from non-self.1 The TLRs, located at the cell membrane, monitor the extracellular space and recognize the presence of particular structures conserved among pathogens called pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Subsequently, a multitude of cytoplasmic receptors were identified as the intracellular counterparts of TLRs, founding the retinoic acid inducible gene-I-like helicase and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor or (NLR) family of proteins among others.2 Studies on these receptors provided further insights into how the innate immune system not only reacts to foreign stimuli, but also distinguishes another class of signals in the form of cellular stress, which were collectively termed danger-associated molecular patterns. Together these receptors are instrumental in initiating an inflammatory reaction, which in turn triggers the cascades of innate and adaptative immune responses. In this review, we will focus on those intracellular receptors that take part in the formation of ‘inflammasomes’, macromolecular complexes able to serve as platforms for inflammatory cytokine activation, in particular for interleukin-1β (IL-1β).

IL-1β, a multifunctional cytokine

IL-1β is a pivotal inflammatory cytokine mainly produced by myeloid cells, which has pleiotropic effects. In the past, it was described as an ‘endogenous pyrogen’ because of its ability to induce fever in animal models.3 Moreover, it was found that excessive production of this cytokine provokes local and systemic manifestations of inflammation, as exemplified by several diseases of genetic or acquired origin, which will be discussed later.4 IL-1β was also called ‘lymphocyte-activating factor’, based on its ability to stimulate T-cell proliferation. More recently, IL-1β was observed to enhance the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into T helper type 2 (Th2) or Th17 cells, the latter being a newly described subset of T cells involved in immune responses to fungi as well as in autoimmunity.5–8 A number of studies also suggest a direct role of IL-1β in the control of pathogenic infections, of fungal, bacterial and viral origin.9–18

As a result of its potent pro-inflammatory properties, production of active IL-1β needs to be tightly controlled. There are two distinct regulatory steps. First, proIL-1β, the biologically inert precursor of IL-1β, is produced in response to inflammatory stimuli such as TLR ligands or inflammatory cytokines. The second step consists of the processing of proIL-1β to generate the mature form of the cytokine. This step is controlled by the inflammasome, a proteolytic complex that is formed after the triggering of specific intracellular receptors (Figs 1 and 2).19–21 Caspase-1, a cysteine protease previously called IL-1β-converting enzyme, is the essential component for the inflammasome’s proteolytic function.20,21

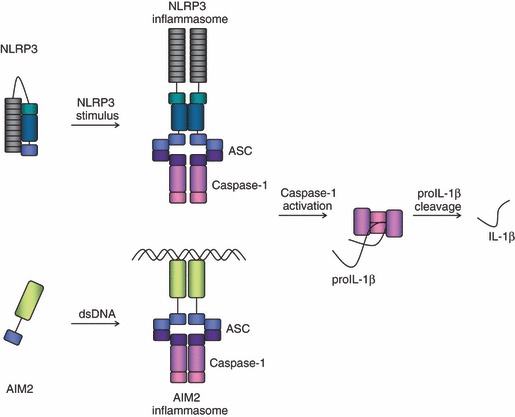

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) family, pyrin domain containing (NLRP3) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) inflammasome complexes. Two prototypical inflammasomes are depicted; while NLRP3 is believed to change conformation and to oligomerize upon ligand sensing, AIM2 is thought to form its complex around its ligand double-stranded (ds) DNA. Caspase-1 is recruited into the complex via the adaptor protein apoptosis speck protein with CARD (ASC). Once in close proximity within the inflammasome complex, caspases are activated through autoproteolytic cleavage and can then process their substrates, as for instance pro-interleukin-1β (proIL-1β).

The inflammasomes

Intracellular receptors forming inflammasomes

To date, four cytoplasmic receptors have been described that form an inflammasome complex: NLR family, pyrin domain containing 1 (NLRP1; also called NALP1), NLRP3 (also called NALP3 or cryopyrin), NLR family, caspase recruitment domain (CARD) containing 4 (NLRC4; also called IPAF) and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2).4,22–29 While AIM2 belongs to the haematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear protein (HIN) family of proteins, NLRP1, NLRP3 and NLRC4 all belong to the NLR family of receptors.

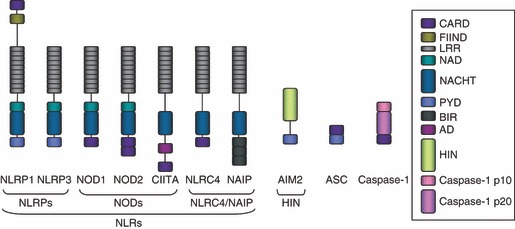

The NLRs are intracellular receptors characterized by a tripartite structure, with a variable N-terminal ‘effector domain’, a central NACHT [NAIP (NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein), CIITA (class II, major histocompatibility complex, transactivator), HET-E (plant het gene product involved in vegetative incompatibility) and TP-1 (telomerase-associated protein 1)] domain and a C-terminal tail of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) (Fig. 1).4,30 These receptors are further subdivided into three clades, based on their specific functions and on the presence of characteristic N-terminal modules that make up their effector domains. The three subfamilies consist of the NOD receptors, the NLRPs and the NLRC4/NAIP clade. The NOD proteins are characterized by the presence of one or more CARDs at their N-terminus. Upon ligand sensing, the two best-known representatives of this subfamily, NOD1 and NOD2, are involved in the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and downstream induction of target inflammatory genes.30 The NLRP receptors share an N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD). Among the 14 human genes belonging to this clade, only a few have been ascribed a function; the most prominently studied are NLRP1 and NLRP3, both of which are instrumental in the formation of an inflammasome structure.28,29 Notably, the NLRP1 gene, unlike NLRP3, carries a C-terminal extension following the LRR region, which codes for a CARD, as depicted in Fig. 1. Lastly, NLRC4 and NAIP, despite being classed together, do not share a common domain organization. From a structural point of view, NLRC4 and NAIP are different, being characterized by an N-terminal CARD and three consecutive baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domains, respectively (Fig. 1). However, they are grouped in the same subfamily based on functional similarities. In fact, NLRC4 forms an inflammasome platform often in association with NAIP.23,31 The NACHT domain, which is found in all the NLRs, belongs to the STAND (signal transduction ATPases with numerous domains) family of NTPases and functions as the central scaffold mediating oligomerization.32 AIM2 shares the presence of a PYD at the N-terminus with the NLRP receptors (Fig. 1). It belongs to the HIN family of proteins and bears a C-terminal HIN domain, previously shown to mediate protein–protein interactions as well as DNA binding.33

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) family of receptors and additional inflammasome components. The typical tripartite structure of NLRs is shown: the effector domain [which can be either a pyrin domain (PYD), a caspase recruitment domain (CARD) or a baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domain], the central NACHT [NAIP (NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein), CIITA (class II, major histocompatibility complex, transactivator), HET-E (plant het gene product involved in vegetative incompatibility) and TP-1 (telomerase-associated protein 1)] domain and the C-terminal LRR. The majority of the NLRs also contain a NACHT-associated domain (NAD). The NLRs are further subdivided into three categories: the NLR family, pyrin domain containing (NLRP), characterized by an N-terminal PYD, the NODs, which have an N-terminal CARD and NLR family, CARD containing 4 (NLRC4)/NAIP, two proteins which often accomplish common tasks. The NLRP3 structure is representative of NLRP2–14, with the exception of NLRP10 that lacks the leucine-rich repeats (LRRs). Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) belongs to the haematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear protein (HIN) family of proteins, and has the characteristic N-terminal PYD and a C-terminal HIN domain. The adaptor protein apoptosis speck protein with CARD (ASC) consists of a PYD and a CARD, important for homotypic CARD–CARD interactions with caspase-1.

These four receptors form inflammasomes in response to their respective stimuli. NLRP1b, one of the isoforms of the NLRP1 gene, can form an inflammasome in response to Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin.28 The NLRP3 inflammasome will assemble upon detection of a plethora of different stimuli, including agents that alter the ionic permeability of the cell membrane, such as pore-forming toxins or ATP, particulate stimuli like monosodium urate crystals, or haemozoin and pathogens such as Candida albicans.4,9–11,29,34,35 Given the heterogeneous nature of the stimuli activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, it is unclear whether NLRP3 itself serves as direct receptor for all of them. It could be envisaged that other receptors, specific to the individual stimuli, are activated and proceed to induce NLRP3 inflammasome formation. An alternative scenario would be that a secondary messenger molecule, which is induced by the different activators, in turn directly activates NLRP3.4,36 NLRC4 is activated upon infection by intracellular Gram-negative bacteria, such as Salmonella typhimurium or Shigella flexneri.23,37 Together with NAIP, NLRC4 can also sense Legionella pneumophila.31 It is important to note that, based on an analogy with the TLRs, we presume that the LRR region of the NLRs represents the ‘ligand binding’ domain; however, this concept awaits experimental proof. In contrast, AIM2 was shown to bind cytoplasmic double-stranded DNA directly through its HIN domain and to subsequently form an inflammasome complex.24,25,27

Molecular structure of inflammasomes

We presume that under resting conditions, NLRs are present in the cytoplasm in a repressed, inactive form.38 Upon stimulation, the receptors undergo a conformational change to expose their NACHT oligomerization domain, the first step towards the formation of the inflammasome complex. AIM2 receptors probably oligomerize and initiate inflammasome formation directly around the bound DNA strand. Upon activation, the NLRP receptors and AIM2 bind and recruit the adaptor protein apoptosis speck protein with CARD (ASC) via a PYD–PYD interaction.19 The ASC protein is small and composed of an N-terminal PYD and a C-terminal CARD. Through its CARD, ASC forms a homotypic interaction with the CARD of caspase-1, the effector arm of the inflammasome complex (Fig. 2). In contrast, NLRP1 and NLRC4 both contain a CARD themselves, and are potentially able to directly recruit caspase-1. The exact contribution of ASC in these two inflammasomes remains to be fully elucidated, although experimental evidence indicates that ASC could increase the stability of the overall structure.37,39 In the case of NLRP3 and AIM2, however, which do not possess a CARD, ASC is strictly required for the formation of their respective inflammasomes, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Caspases are a family of cysteine proteases that cleave their substrates after an aspartic acid residue. While the majority of caspases are well known for their role in the apoptotic process, a few so called ‘inflammatory caspases’, are important for the proteolytic activation and secretion of inflammatory mediators.40 Caspase-1, -4, -5 and -12 in humans and caspase-1, -11 and -12 in the mouse are known as inflammatory caspases.

In resting cells, caspase-1 is present in an inactive state; however, once recruited to an inflammasome platform, caspases can proteolytically activate each other. Following proteolytic processing, caspase-1 consists of 10 (p10) and 20 (p20) kilodalton subunits. Once activated, caspase-1 converts proIL-1β, which has a molecular weight of approximately 31 kilodaltons, into its active 17 kilodalton form (Fig. 2).20,21 Although secondary to caspase-1 in the catalytic activity, caspase-5, and its murine homologue caspase-11 interact with caspase-1 to increase its proteolytic activity.19,41 Besides IL-1β, caspase-1 can cleave other substrates such as the inflammatory cytokine IL-18 or the apoptotic caspase-7.42–44 Cleavage of caspase-7 downstream of caspase-1 might provide a mechanistic link to pyroptosis, a type of caspase-1-dependent inflammatory cell death.45

The role of inflammasomes in human diseases

The importance of inflammasomes in human disease is becoming increasingly appreciated. The initial link between inflammasomes and disease was provided by the identification of mutations in the NLRP3 gene in patients with an autoinflammatory syndrome, which we now know as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome.46 Following this discovery, researchers uncovered a functional connection between the disease and the excessive, dysregulated IL-1β production.47 The observation that patients, which were treated with IL-1β inhibitors showed a dramatic clinical response provided definitve proof that IL-1β plays a fundamental role in this disease.48,49 A further clear link between inflammasomes and human disorders can be found in crystal-induced arthritic syndromes. Based on the observation that urate crystals induce IL-1β production through the NLRP3 inflammasome, subsequent animal and clinical studies with IL-1 inhibitors were performed. These trials demonstrated the efficacy of IL-1β-targeted treatments in alleviating the symptoms of acute gout, an arthritic condition caused by the urate crystals.50,51

As already mentioned above, several pathogens were found to induce inflammasome activation and IL-1β production, but the clinical impact of these observations has not been thoroughly assessed in humans. One such finding that may be of clinical relevance is the ability of haemozoin, a degradation product of haemoglobin produced during malarial infection, to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome.35,52 If excessive IL-1β production would indeed contribute to complications such as cerebral malaria, then inhibition of this cytokine could be helpful in disease management.

Interleukin-1 inhibitors have also been tested in other inflammatory diseases in which the cytokine is thought to play a role and where patients have not responded to conventional therapies. Reports have been published showing the efficacy of this treatment in conditions such as systemic onset juvenile arthritis53 and in Schnitzler syndrome.54 This suggests that inflammasome activation may also play a role in the pathogenesis of these syndromes.

Finally, emerging data suggest that inflammasome activation and production of IL-1β also play a role in diseases that hitherto were not thought to be inflammatory in nature. An illustration of such a development is diabetes mellitus. Recent research has shown that metabolic stress caused for example by hyperglycaemia can indeed induce islet cell inflammation and production of inflammatory cytokines.55,56 The clinical relevance of this disease pathway was further confirmed by a randomized-controlled trial showing that IL-1 inhibition reduced hyperglycaemia in patients with type II diabetes.57 These findings raise the question of the role of IL-1 production in other chronic inflammatory diseases such as osteoarthritis and atherosclerosis, which future research will address.

Negative regulation of inflammasome activity

To control injury effectively, the acute inflammatory response has to be quickly and efficiently engaged. However, this response also has to be tightly controlled and switched off once the inducing stimuli are no longer present to avoid unnecessary collateral damage. In this context, negative feedback loops are an important aspect of the inflammatory response. Several proteins, both of endogenous as well as of microbial origin, have been shown to be implicated in these regulatory mechanisms. In fact, inflammation appears to favour the progression of infection by certain pathogens whereas the decrease in IL-1β production helps other microbes to evade detection by immune cells.58–61

Direct inhibitory mechanisms

Based on genomic and structural studies, several genes in the human genome were predicted to interfere with the formation of the inflammasome, including COP (CARD-only protein), INCA (inhibitory CARD) and ICEBERG. They have subsequently all been shown to inhibit caspase-1 activation in vitro.62,63 All three proteins contain a CARD, so they are believed to act as decoys thereby interfering with the assembly of a functional inflammasome. However, the importance of these regulators is uncertain because no variants of their genes have been associated with inflammatory diseases to date and they are completely absent in the mouse genome.

Another CARD-containing protein, caspase-12, has also been proposed to act as a negative regulator of caspase-1 by physically associating with caspase-1 and inhibiting its activity.64 Indeed, caspase-12-deficient mice present higher levels of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, as well as more efficient clearance of bacterial infections. Interestingly, as the result of a sequence polymorphism, most humans only express a truncated form of caspase-12 consisting of the CARD.65 However, a small population of humans has been identified that express the full-length form. Studies on these two isoforms suggest that full-length caspase-12, in contrast to the truncated form, can be linked to lipopolysaccharide hyporesponsiveness. This observation implicates that the mechanism of inhibition used by caspase-12 most probably encompasses more than a simple homotypic CARD–CARD interaction, and that further investigation is required to fully elucidate this negative regulation.

In analogy with the CARD-containing inhibitors, proteins containing a PYD motif can also impede inflammasome formation. Pyrin is a protein that has been suggested to negatively affect inflammasome function in this way.66–68 The gene encoding this protein is mutated in patients with familial Mediterranean fever, a disease characterized by episodic fever and serosal or synovial inflammation. In fact, pyrin-deficient mice show increased endotoxic sensitivity, and higher caspase-1 activity.68 However, over-expression of this protein also results in a pro-inflammatory phenotype, which makes it difficult to interpret the role of pyrin and the nature of its disease-associated mutations.69 In further support of the inflammasome-regulating function of pyrin, patients suffering from pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne (PAPA) syndrome, an inflammatory disease linked to excessive IL-1β production, have a mutation in proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 1, a protein interacting with pyrin.70–72

Two other human proteins that contain a PYD, pyrin-only protein 1 (POP1) and POP2, have also been shown to influence inflammasome activity in vitro.73,74 Originally, POP1 was found to enhance ASC-dependent IL-1β secretion, whereas POP2 decreased it. However, the absence of POP1 and POP2 orthologues in the mouse genome renders it difficult to assess their contribution to the regulation of the inflammatory response in vivo. In addition, viral PYD-containing proteins have been identified in the genome of poxviruses; consistent with a regulatory function of these proteins in inflammation, infection of cells by viruses lacking these genes showed increased inflammasome activity and IL-1β secretion.60

The AIM2 inflammasome also has its specific mechanism of regulation. Concurrent with its discovery, it was reported that p202, another member of the HIN-family, can antagonize AIM2-dependent activation of caspase-1.26 Both proteins efficiently bind double-stranded DNA through their HIN domains. However, p202 lacks a PYD, thereby potentially sequestering DNA molecules without downstream signalling, which may explain how it counteracts the activity of the AIM2 inflammasome. Moreover, p202 can bind to AIM2 directly.33 Hence, the mechanism by which p202 negatively regulates AIM2 may encompass both the sequestration of AIM2 itself and the competition for DNA binding.

Serine proteinase inhibitors, or serpins, are a family of proteins that bind and block the active site of its target proteases, thereby regulating their proteolytic activity. Although most serpins inhibit serine proteases, a few members of the family have been found to interact with cysteine proteases. Furthermore, serpins have also been identified in pathogens; the caspase inhibitor cytokine response modifier A (CrmA) encoded by the cowpox virus, has been shown to interact and block the activity of caspase-1.59 By structural analogy to CrmA, serpinB9 (also called proteinase inhibitor-9 in humans or serine proteinase inhibitor-6) was found to be involved in the inhibition of caspase-1 activation and consequently IL-1β production.59,75,76 Another member of the serpin family, serpinB2 (also called plasminogen activator inhibitor 2; PAI-2), has also been implicated in the negative regulation of caspase-1.77 In fact, expression of PAI-2 in macrophages deficient in NF-κB signalling, blocked their spontaneous IL-1β secretion, indicating that this serpin might serve as a negative regulator of caspase-1. However, the exact mechanism of these regulatory proteins and the physiological context in which they might act are largely unexplored.

Further leads in our understanding of inflammasome regulation were found in the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans. In the nematode, the protein Caenorhabditis elegans death 4 (CED-4) forms an ‘archetypic’ complex that activates the catalytically competent protein CED-3, which is highly homologous to caspases. CED-9, an orthologue of the Bcl-2 protein, is able to suppress CED-3 activation by interfering with the CED-4-dependent step. By analogy to CED-9, it has been found that NLRP1 inflammasome activity is reduced by the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and BCL-XL.78

Indirect or upstream inhibitory signals

It was recently reported that Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection interferes with inflammasome activity.61 In fact, incubation of infected macrophages with IL-1β can reverse the block in phagosome maturation and the reduction in bactericidal activity induced by these pathogens. Surprisingly, a gene encoding a putative Zn2+ metalloprotease is responsible for the decrease in inflammasome activity and subsequent caspase-1 cleavage. Nevertheless, no information is yet available on whether this protein directly interacts with components of the inflammasome and its exact mechanism of action.

We recently observed that murine effector and memory CD4+ T cells abolish macrophage inflammasome activity and subsequent IL-1β release in a cognate way.79 This finding reveals a cell-mediated mechanism of inflammasome inhibition, whereby activated T cells suppress innate immune cell inflammation during the late phases of primary responses or upon secondary challenges. The suppression of the inflammasome function was recapitulated by incubation of macrophages with selected ligands of the tumour necrosis factor family expressed by activated T cells, such as CD40 ligand. A possibly related observation describes a mouse model in which defective NF-κB signalling is characterized by a strong inflammatory phenotype as the result of spontaneous inflammasome activity and release of high amounts of IL-1β.77 These data challenge the classical view of NF-κB as an important pro-inflammatory transcription factor; it is conceivable that depending on the level and quality of the inflammatory signals, downstream mediators such as NF-κB, can act as negative regulators of inflammasome activity, and so prevent the detrimental effects of a disproportionate reaction.

Concluding remarks

Over the past decade, we have witnessed the discovery of the inflammasome and gained an understanding of its effects on innate immunity. Although different forms of inflammasome complexes have been identified as well as the stimuli that trigger them, our knowledge of how formation of the inflammasomes is initiated remains incomplete. Similarly, the study of the mechanisms that are able to repress inflammasome activity requires further intensive efforts. Additionally, how the endogenous inhibitors are themselves regulated remains wholly unexplored. This area of research is crucial to fully appreciate the complexity of the inflammatory response and in particular to understand its dysregulation in inflammatory diseases.

Given the potency and the multiple functions of IL-1β, the existence of additional regulatory feedback loops controlling its production is likely. In the future, further progress in the field of endogenous and microbial inflammasome inhibitory mechanisms could allow for a better understanding of poorly characterized inflammatory diseases and may provide us with new opportunities for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Mirjam Eckert for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AD

activation domain

- AIM2

absent in melanoma 2

- ASC

apoptosis speck protein with CARD

- BCL

B-cell lymphoma

- CARD

caspase recruitment domain

- CED

Caenorhabditis elegans death

- CIITA

class II, major histocompatibility complex, transactivator

- CrmA

cytokine response modifier A

- FIIND

function to find

- HIN

haematopoietic interferon-inducible nuclear protein

- IL

interleukin

- LRR

leucine-rich repeat

- NACHT

NAIP, CIITA, HET-E (plant het gene product involved in vegetative incompatibility) and TP-1 (telomerase-associated protein 1)

- NAD

NACHT-associated domain

- NAIP

NLR family, apoptosis inhibitory protein

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NLR

NOD-like receptor or NOD and LRR containing

- NLRC

NLR family, CARD containing

- NLRP

NLR family, pyrin domain containing

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- PAI-2

plasminogen activator inhibitor 2

- PYD

pyrin domain

- POP

pyrin-only protein

- Th

T helper

- TLR

toll-like receptor

Disclosure

The authors have no competing financial interests nor conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meylan E, Tschopp J, Karin M. Intracellular pattern recognition receptors in the host response. Nature. 2006;442:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinarello CA. Infection, fever, and exogenous and endogenous pyrogens: some concepts have changed. J Endotoxin Res. 2004;10:201–22. doi: 10.1179/096805104225006129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKean DJ, Nilson A, Beck BN, Giri J, Mizel SB, Handwerger BS. The role of IL 1 in the antigen-specific activation of murine class II-restricted T lymphocyte clones. J Immunol. 1985;135:3205–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kool M, Petrilli V, De Smedt T, et al. Cutting edge: alum adjuvant stimulates inflammatory dendritic cells through activation of the NALP3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2008;181:3755–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immun. 2007;8:942–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meng G, Zhang F, Fuss I, Kitani A, Strober W. A mutation in the Nlrp3 gene causing inflammasome hyperactivation potentiates Th17 cell-dominant immune responses. Immunity. 2009;30:860–74. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hise AG, Tomalka J, Ganesan S, Patel K, Hall BA, Brown GD, Fitzgerald KA. An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:487–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joly S, Ma N, Sadler JJ, Soll DR, Cassel SL, Sutterwala FS. Cutting edge: Candida albicans hyphae formation triggers activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J Immunol. 2009;183:3578–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, et al. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature. 2009;459:433–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza a virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity. 2009;30:556–65. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas PG, Dash P, Aldridge JR, et al. The intracellular sensor NLRP3 mediates key innate and healing responses to influenza A virus via the regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2009;30:566–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichinohe T, Lee HK, Ogura Y, Flavell R, Iwasaki A. Inflammasome recognition of influenza virus is essential for adaptive immune responses. J Exp Med. 2009;206:79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara-Tejero M, Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Grant EP, Bertin J, Coyle AJ, Flavell RA, Galan JE. Role of the caspase-1 inflammasome in Salmonella typhimurium pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1407–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sansonetti PJ, Phalipon A, Arondel J, Thirumalai K, Banerjee S, Akira S, Takeda K, Zychlinsky A. Caspase-1 activation of IL-1beta and IL-18 are essential for Shigella flexneri-induced inflammation. Immunity. 2000;12:581–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuji NM, Tsutsui H, Seki E, Kuida K, Okamura H, Nakanishi K, Flavell RA. Roles of caspase-1 in Listeria infection in mice. Int Immunol. 2004;16:335–43. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Dixit VM, Monack DM. Innate immunity against Francisella tularensis is dependent on the ASC/caspase-1 axis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1043–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, Allen H, Banerjee S, et al. Mice deficient in IL-1 beta-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature IL-1 beta and resistant to endotoxic shock. Cell. 1995;80:401–11. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuida K, Lippke JA, Ku G, Harding MW, Livingston DJ, Su MS, Flavell RA. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science (New York, NY) 1995;267:2000–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, et al. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458:509–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M, Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, Latz E, Fitzgerald KA. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458:514–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts TL, Idris A, Dunn JA, et al. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science (New York, NY) 2009;323:1057–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burckstummer T, Baumann C, Bluml S, et al. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immun. 2009;10:266–72. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyden ED, Dietrich WF. Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat Genet. 2006;38:240–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kufer TA, Fritz JH, Philpott DJ. NACHT-LRR proteins (NLRs) in bacterial infection and immunity. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lightfield KL, Persson J, Brubaker SW, et al. Critical function for Naip5 in inflammasome activation by a conserved carboxy-terminal domain of flagellin. Nat Immun. 2008;9:1171–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Aravind L. STAND, a class of P-loop NTPases including animal and plant regulators of programmed cell death: multiple, complex domain architectures, unusual phyletic patterns, and evolution by horizontal gene transfer. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludlow LE, Johnstone RW, Clarke CJ. The HIN-200 family: more than interferon-inducible genes? Exp Cell Res. 2005;308:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–32. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dostert C, Guarda G, Romero JF, et al. Malarial hemozoin is a Nalp3 inflammasome activating danger signal. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant C, Fitzgerald KA. Molecular mechanisms involved in inflammasome activation. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki T, Franchi L, Toma C, et al. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poyet JL, Srinivasula SM, Tnani M, Razmara M, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Identification of Ipaf, a human caspase-1-activating protein related to Apaf-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28309–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, et al. Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:713–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:10–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang S, Miura M, Jung YK, Zhu H, Li E, Yuan J. Murine caspase-11, an ICE-interacting protease, is essential for the activation of ICE. Cell. 1998;92:501–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80943-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu Y, Kuida K, Tsutsui H, et al. Activation of interferon-gamma inducing factor mediated by interleukin-1beta converting enzyme. Science (New York, NY) 1997;275:206–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghayur T, Banerjee S, Hugunin M, et al. Caspase-1 processes IFN-gamma-inducing factor and regulates LPS-induced IFN-gamma production. Nature. 1997;386:619–23. doi: 10.1038/386619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD, Van Damme P, et al. Targeted peptidecentric proteomics reveals caspase-7 as a substrate of the caspase-1 inflammasomes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2350–63. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800132-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:99–109. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle–Wells syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;29:301–5. doi: 10.1038/ng756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, McDermott MF, Hawkins PN, Tschopp J. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle–Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20:319–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, Aganna E, McDermott MF. Spectrum of clinical features in Muckle–Wells syndrome and response to anakinra. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:607–12. doi: 10.1002/art.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, et al. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2416–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.So A, Desmedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terkeltaub R, Sundy J, Schumacher HR, et al. The IL-1 inhibitor rilonacept in treatment of chronic gouty arthritis: results of a placebo-controlled, cross-over pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1613–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Patel P, Palucka AK, Chaussabel D, Banchereau J. Pure hemozoin is inflammatory in vivo and activates the NALP3 inflammasome via release of uric acid. J Immunol. 2009;183:5208–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pascual V, et al. How the study of children with rheumatic diseases identified interferon-alpha and interleukin-1 as novel therapeutic targets. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:39–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Koning HD, Bodar EJ, Simon A, van der Hilst JC, Netea MG, van der Meer JW. Beneficial response to anakinra and thalidomide in Schnitzler’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:542–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.045245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Donath MY, Boni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Ehses JA. Islet inflammation impairs the pancreatic beta-cell in type 2 diabetes. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:325–31. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00032.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2009;11:136–40. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Volund A, Ehses JA, Seifert B, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath MY. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1517–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monack DM, Hersh D, Ghori N, Bouley D, Zychlinsky A, Falkow S. Salmonella exploits caspase-1 to colonize Peyer’s patches in a murine typhoid model. J Exp Med. 2000;192:249–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ray CA, Black RA, Kronheim SR, Greenstreet TA, Sleath PR, Salvesen GS, Pickup DJ. Viral inhibition of inflammation: cowpox virus encodes an inhibitor of the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Cell. 1992;69:597–604. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnston JB, Barrett JW, Nazarian SH, Goodwin M, Ricciuto D, Wang G, McFadden G. A poxvirus-encoded pyrin domain protein interacts with ASC-1 to inhibit host inflammatory and apoptotic responses to infection. Immunity. 2005;23:587–98. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Master SS, Rampini SK, Davis AS, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis prevents inflammasome activation. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:224–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.da Cunha JP, Galante PA, de Souza SJ. Different evolutionary strategies for the origin of caspase-1 inhibitors. J Mol Evol. 2008;66:591–7. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kersse K, Vanden Berghe T, Lamkanfi M, Vandenabeele P. A phylogenetic and functional overview of inflammatory caspases and caspase-1-related CARD-only proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1508–1511. doi: 10.1042/BST0351508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saleh M, Mathison JC, Wolinski MK, et al. Enhanced bacterial clearance and sepsis resistance in caspase-12-deficient mice. Nature. 2006;440:1064–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saleh M, Vaillancourt JP, Graham RK, et al. Differential modulation of endotoxin responsiveness by human caspase-12 polymorphisms. Nature. 2004;429:75–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chae JJ, Wood G, Masters SL, Richard K, Park G, Smith BJ, Kastner DL. The B30.2 domain of pyrin, the familial Mediterranean fever protein, interacts directly with caspase-1 to modulate IL-1beta production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9982–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602081103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Papin S, Cuenin S, Agostini L, et al. The SPRY domain of Pyrin, mutated in familial Mediterranean fever patients, interacts with inflammasome components and inhibits proIL-1beta processing. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1457–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chae JJ, Komarow HD, Cheng J, Wood G, Raben N, Liu PP, Kastner DL. Targeted disruption of pyrin, the FMF protein, causes heightened sensitivity to endotoxin and a defect in macrophage apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2003;11:591–604. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yu JW, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Datta P, et al. Pyrin activates the ASC pyroptosome in response to engagement by autoinflammatory PSTPIP1 mutants. Mol Cell. 2007;28:214–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shoham NG, Centola M, Mansfield E, Hull KM, Wood G, Wise CA, Kastner DL. Pyrin binds the PSTPIP1/CD2BP1 protein, defining familial Mediterranean fever and PAPA syndrome as disorders in the same pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135380100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferguson PJ, Bing X, Vasef MA, et al. A missense mutation in pstpip2 is associated with the murine autoinflammatory disorder chronic multifocal osteomyelitis. Bone. 2006;38:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grosse J, Chitu V, Marquardt A, et al. Mutation of mouse Mayp/Pstpip2 causes a macrophage autoinflammatory disease. Blood. 2006;107:3350–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stehlik C, Krajewska M, Welsh K, Krajewski S, Godzik A, Reed JC. The PAAD/PYRIN-only protein POP1/ASC2 is a modulator of ASC-mediated nuclear-factor-kappa B and pro-caspase-1 regulation. Biochem J. 2003;373:101–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bedoya F, Sandler LL, Harton JA. Pyrin-only protein 2 modulates NF-kappaB and disrupts ASC : CLR interactions. J Immunol. 2007;178:3837–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Young JL, Sukhova GK, Foster D, Kisiel W, Libby P, Schonbeck U. The serpin proteinase inhibitor 9 is an endogenous inhibitor of interleukin 1beta-converting enzyme (caspase-1) activity in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1535–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Annand RR, Dahlen JR, Sprecher CA, et al. Caspase-1 (interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme) is inhibited by the human serpin analogue proteinase inhibitor 9. Biochem J. 1999;342(Pt 3):655–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greten FR, Arkan MC, Bollrath J, et al. NF-kappaB is a negative regulator of IL-1beta secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKbeta. Cell. 2007;130:918–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bruey JM, Bruey-Sedano N, Luciano F, et al. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL regulate proinflammatory caspase-1 activation by interaction with NALP1. Cell. 2007;129:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guarda G, Dostert C, Staehli F, Cabalzar K, Castillo R, Tardivel A, Schneider P, Tschopp J. T cells dampen innate immune responses through inhibition of NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes. Nature. 2009;460:269–73. doi: 10.1038/nature08100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]