Abstract

Objective

To explore racial/ethnic difference in OROS-methylphenidate (OMPH) efficacy when added to nicotine patch and counseling for treating nicotine dependence among smokers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Method

Participants were adult smokers with ADHD (202 whites and 51 non-whites) randomly assigned to OMPH or placebo in a multi-site, randomized controlled trial. Study outcomes were complete, prolonged, and point-prevalence abstinence at the end of treatment, and weekly ratings of ADHD symptoms, tobacco withdrawal symptoms, and desire to smoke.

Results

The rate of four-week complete abstinence (no slips or lapses) was significantly higher with OMPH than placebo among non-white (OMPH=42.9%, placebo =13.3%, χ2(1)=5.20, p=0.02) but not white participants (OMPH=23.1%, placebo =23.5%, χ2(1)=0.00, p=0.95). Patterns of prolonged and point-prevalence abstinence among non-whites were similar but fell short of statistical significance. OMPH reduced ADHD symptoms in both race/ethnic groups, and produced greater reductions in desire to smoke and withdrawal symptoms among the non-white than white participants. Change in desire to smoke, but not in withdrawal or ADHD symptoms predicted abstinence. The ability of OMPH to reduce desire to smoke among non-whites appeared to mediate the medication’s positive effect on abstinence.

Conclusion

Differential efficacy favoring non-whites of a medication for achieving smoking cessation is a potentially important finding that warrants further investigation. OROS-MPH could be an effective treatment for nicotine dependence among a subgroup of smokers.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, race/ethnic differences, ADHD, OROS-Methylphenidate

1. INTRODUCTION

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neuropsychiatric condition that begins in childhood and often persists to adulthood (APA, 1994). Evidence that nicotine ameliorates inattentiveness (Conners et al, 1996) and reduces deficits in dopaminergic function related to inattention problems (Volkow et al, 2007) would suggest that treatment of ADHD symptoms could facilitate smoking abstinence. A clinical trial was conducted to test the efficacy of osmotic release OROS-methylphenidate (OMPH), a treatment for ADHD as adjunctive medication for improving cessation rates among smokers with ADHD; the primary outcome analysis found that OMPH improved ADHD symptoms but did not increase smoking cessation (Winhusen et al, in press).

The present study explored the effects of race/ethnicity. Prior open label studies of treatment aids for smokers, i.e., nicotine patch and/or bupropion, have found lower abstinence rates in non-white than white smokers (Covey et al, 2008; Cropsey et al, 2008; Miller et al, 2005); placebo-controlled efficacy of any cessation aid by race/ethnicity, however, is unknown. A trial of 579 children with ADHD found similar benefit of methylphenidate for whites and non-whites (Arnold et al, 2003); however, no prior study has reported ethnic differences in treatment outcome among adults with ADHD. This study addresses these knowledge gaps by investigating racial/ethnic differences in: a) smoking abstinence outcomes in response to OMPH versus placebo (Pbo) when added to nicotine patch and behavioral counseling; b) the effects of OMPH on ADHD symptoms, tobacco withdrawal symptoms, and desire to smoke; and c) the effect of changes in those symptoms on smoking abstinence.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

Details of the protocol are described elsewhere (Winhusen et al, in press). Briefly, the main inclusion criteria were: smoke at least 10 cigarettes daily, 18–55 years old, and meet DSM-IV criteria for ADHD as assessed by the Adult Clinical Diagnostic Scale version 1.2 (Adler and Cohen, 2004). Exclusion criteria included a positive urine drug screen, current psychiatric illness, current treatment for ADHD or nicotine dependence; for women, pregnancy, breastfeeding, or unwillingness to use adequate birth control. The study design was randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and consisted of a four-week pre-quit phase and a six-week planned abstinence period. Participants received OMPH or placebo during weeks 1–11, used 21 mg. nicotine patches daily beginning on the target quit date (i.e., the fifth day of Week 4), and received smoking cessation counseling at each weekly clinic visit.

2.2. Outcomes and measures

The main study outcomes were complete, prolonged, and point-prevalence abstinence. Complete (no slips or lapses) and prolonged abstinence rates (slips or lapses allowed) were based on abstinence reports during Weeks 7–10. Point-prevalence abstinence was not smoking during the seven days prior to the end of Week 10. Daily smoking abstinence was assessed using the time-line follow-back method (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) and verified by expired carbon monoxide <8 parts per million.

Secondary outcomes were changes (from baseline to Week 11) in ADHD symptoms, tobacco withdrawal symptoms, and desire to smoke. The ADHD Rating Scale (DuPaul and Power, 1998) was administered at baseline, weeks 1–4, and biweekly during weeks 7–11. The Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Symptoms Scale (MNWS) which includes items on desire to smoke, anger/irritability, anxiety/nervousness, difficulty concentrating, depression, impatience/restlessness, hunger, and awakening at night (Etter and Hughes, 2006), was self-administered by participants at baseline and weeks 5–11. We examined “desire to smoke” (also referred to as craving) separately from a 7-item MNWS score.

The main variables for predicting abstinence were OMPH versus placebo (Pbo) treatment, and white versus non-white race/ethnicity. Race/ethnicity, based on self-report, was categorized into white non-Hispanic (Wh) and non-white (NW); the latter group included African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and Other. We further categorized the sample into four subgroups by race/ethnicity and treatment assignment into Wh-OMPH, Wh-Pbo, NW-OMPH, and NW-Pbo. We also examined the effects of demographics (age, gender, and education), smoking history (number of cigarettes smoked daily, age of smoking onset, number of past attempts to quit), and level of nicotine dependence using the subject’s score on the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al, 1991).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The intent-to-treat method was used to assess treatment effects. We performed the Wald chi-square test to analyze differences among the study groups. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05. We used the generalized linear model (GLM) to examine changes from baseline through the end of treatment for ADHD symptoms, tobacco withdrawal symptoms, and desire to smoke, modeling each of the latter symptom clusters as a function of race/ethnicity by treatment, time of assessment, and the baseline value of the symptom. The interactions of race/ethnicity with treatment and time were tested. The participant was a random variable in the models. To analyze the relationship among abstinence, race/ethnicity by treatment, and change scores on the symptom clusters, we used GLM, deriving the adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We entered clinical sites as random effects in the models. The GLM methodology handled within-site correlation; PROC Glimmix (SAS 9.1.3.) was used.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of the sample

Two hundred fifty-five participants (7% of 3,865 respondents to our recruitment efforts) who met eligibility criteria were randomized. Two participants who did not answer the race/ethnicity question were excluded. Of the remaining 253, 79.8% were white, 5.9% African American, 6.3% Hispanic, and 7.9% Asian/Other; the three non-white groups, taken together, comprised one fifth (20.2%) of the sample. The mean age was 38.8 years (SD=10); 56.5% were male; the mean years of schooling was 14.4 years (SD=2.4)

The four treatment/ethnicity subgroups did not vary by age, gender, educational level, or baseline FTND and desire to smoke. Whites smoked more cigarettes daily (Wh-OMPH=21.2; Wh-Pbo=20.9; NW-OMPH=15.4; NW-Pbo=17.8; χ2(3)=13.3, p=0.004); whereas non-whites reported higher baseline withdrawal symptoms (Wh-OMPH=11.1; Wh-Pbo=11.9; NW-OMPH=14.8; NW-Pbo=13.8; χ2(3)=10.56, p=0.01). Within race/ethnic groups, no differences by treatment assignment on the sample characteristics were observed.

Participants randomized to OMPH reported more treatment emergent adverse events (TEAE). The most common TEAE (>10%) were headache, nervousness, anxiety, insomnia, nasopharyngitis, decreased appetite, nausea, fatigue, and dry mouth. The frequency of TEAE did not differ by race/ethnicity and was unrelated to abstinence at the end of treatment. Rates of retention and compliance with taking the study medications were high (84.3% and 94%, respectively), and did not vary by race/ethnicity or treatment.

The majority of OMPH subjects correctly guessed their treatment assignment (84.2% non-white and 84.4% white). Correct guesses of treatment assignment were made less frequently by the placebo group, with no significant difference by race/ethnicity (47.8% non-white and 60.2% white, p=0.29).

3.2. Abstinence rates by race/ethnicity and treatment status

For the entire sample, the abstinence rates were 23.7%, 42.7%, and 39.1% for complete, prolonged, and point-prevalence abstinence, respectively. The complete abstinence rates for OMPH and placebo differed significantly among non-whites (NW-OMPH=42.9%; NW-Pbo=13.3%, χ2(1)=5.20, p=0.02) but not among whites (Wh-OMPH=23.1%, Wh-Pbo=23.5%, χ2(1)=0.00, p=0.95). Similar patterns of higher rates with OMPH than placebo occurred among non-whites for prolonged and point-prevalence abstinence, but these differences fell short of statistical significance. Prolonged and point-prevalence abstinence rates did not differ by treatment group among whites.

3.3. ADHD symptoms, tobacco withdrawal symptoms, and desire to smoke

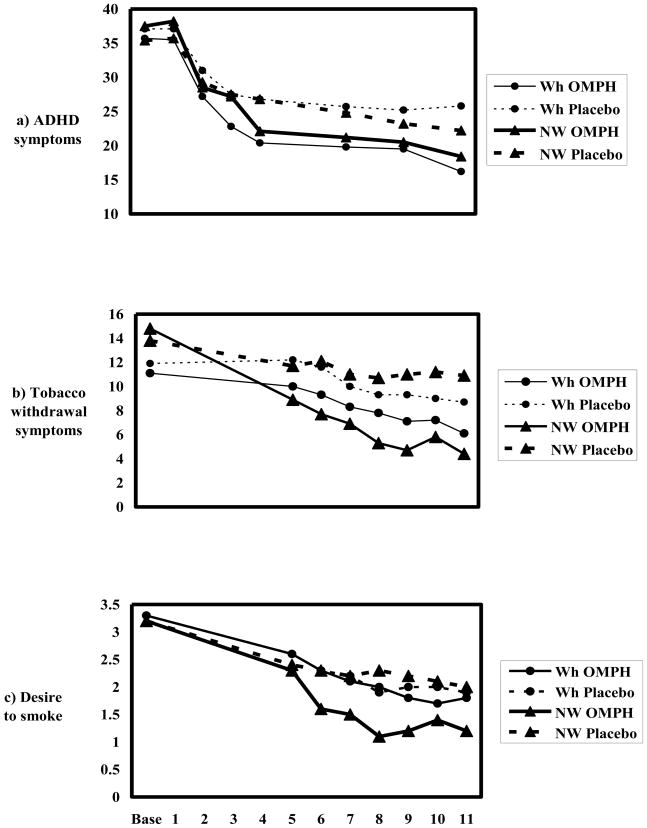

Figure 1a shows that ADHD symptoms declined in all groups during the trial. The linear model predicting ADHD symptoms yielded a significant treatment by time interaction (χ2(1)=11.87, p=0.0006), reflecting the greater decline over time with OMPH than placebo. There was no significant difference in medication effect by race/ethnicity, and no interactions between ethnicity and treatment or time.

Figure 1.

Symptom scores from baseline to the end of treatment. Numbers on the x-axis indicate the week on which each measure was obtained. Non-white (triangles), white (circles), OMPH (—), placebo (- -)

Figure 1b shows that withdrawal symptoms declined in all groups, more so with OMPH in both race/ethnic groups, and the medication-placebo difference is greater among non-whites. The linear model yielded a significant main effect of treatment (χ2 (1)=16.13, p<0.0001), and a significant treatment by race/ethnic group interaction (χ2(1)=4.44, p=0.04).

For desire to smoke, Figure 1c shows the largest decline among the non-whites on OMPH. The medication-placebo difference appears substantial among the non-whites; no medication-placebo difference is apparent among whites. The linear model yielded a trend towards a treatment by ethnic group interaction effect (χ2(1)=3.68, p=0.0549) reflecting a medication-placebo difference among nonwhites and no difference among the whites.

3.4. Prediction of complete abstinence

Mixed effects models for complete abstinence are shown in Table 1. In the initial model (Table 1, Model A) with non-whites on placebo as the reference group, the odds ratio for the non-white/OMPH group was significant; the odds ratios for white OMPH and placebo groups were not significant. The treatment by ethnicity interaction was significant (χ2(1)=4.35, p-value=0.04). In the models for prolonged abstinence and point-prevalence abstinence (data not shown), the interactive effects of treatment by race/ethnicity were not significant.

Table 1.

The mixed effects models on complete abstinence. Subjects are 253 adult smokers with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

| Model A | Model B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Race/ethnicity by treatment | ||||

| White-OMPH1 (N=104) | 2.57 | 0.76 – 8.66 | 1.83 | 0.51 – 6.65 |

| White-Placebo (N=98) | 2.73 | 0.80 – 9.28 | 1.84 | 0.51 – 6.68 |

| Non-white-OMPH1 (N=21) | 5.28** | 1.24 – 22.60 | 4.15 | 0.85 – 20.30 |

| Non-white-Placebo (N=30) (reference) | 1.00 | |||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day | 0.94* | 0.89 – 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.90 – 1.03 |

| Age of smoking onset | 1.05 | 0.95 – 1.17 | 1.02 | 0.91 – 1.15 |

| Number of quit attempts | 0.99 | 0.95 – 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.95 – 1.03 |

| Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence | 1.04 | 0.87 – 1.25 | 1.04 | 0.86 – 1.26 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.00 – 1.08 | 1.03 | 0.99 – 1.07 |

| Male gender | 1.40 | 0.72 – 2.70 | 1.01 | 0.50 – 2.06 |

| Number of years education | 1.10 | 0.97 – 1.25 | 1.12 | 0.97 – 1.28 |

| Symptom changes (baseline to end-of-treatment) | ||||

| ADHD2 symptoms | 0.99 | 0.96 – 1.02 | ||

| Tobacco withdrawal | 1.04 | 0.98 – 1.10 | ||

| Desire to smoke | 0.56*** | 0.41 – 0.75 | ||

OROS-methylphenidate

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

When changes in ADHD symptoms, tobacco withdrawal symptoms, and desire to smoke were added (Table 1, Model B), only change in desire to smoke significantly predicted complete abstinence. The effect of OMPH versus placebo among non-whites was attenuated and no longer significant. The ability of OMPH to reduce desire to smoke among non-whites appeared to have partially mediated the medication’s positive effect on complete abstinence among non-whites.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this exploratory study is the first to find a positive response to the active medication relative to placebo among non-white smokers that is not seen among their white counterparts. Consistent with outcomes in open trials of smoking cessation aids, the rates of complete abstinence in the placebo group were lower among non-white than white participants (13.3% vs. 23.5%, respectively). Thus, the superior response to OMPH among non-whites reflects a positive response to the medication, not simply a better prognosis group. A second set of findings was that reduced craving strongly predicted abstinence and that reduced craving, but not improvement of ADHD symptoms, mediated the positive response among non-whites suggesting that processes related to the tobacco addiction rather than to management of ADHD symptoms were more directly involved in the cessation process.

Several study limitations warrant caution when considering potential mechanisms that might explain our findings--the post-hoc analysis, the ethnic heterogeneity and small sample size of the non-white group, self-identification of the race/ethnicity variable, and selection biases characteristic of clinical trials. Furthermore, the OMPH benefit became evident with complete abstinence only, the most rigorous abstinence measure, which produced the lowest placebo rate. In general, low placebo response rates produce higher treatment effects.

With these caveats in mind, we offer some possible explanations. 1) Non-whites had reported smoking fewer cigarettes per day and higher withdrawal symptom ratings; these behaviors could indicate greater nicotine vulnerability, and thus, greater sensitivity to a nicotine analog such as OMPH. The concomitant use of nicotine patch and methylphenidate could have produced additive or synergistic benefit for non-whites beyond that derived by whites. 2) A related, culturally-based explanation could lie in different meanings of the ADHD symptom items among the ethnic groups, resulting in ADHD patients with superficially similar syndromes, but varying underlying neural mechanisms and sensitivity to OMPH. Differences in response to ADHD symptoms among African-American and Caucasian parents of children with ADHD have been reported (Miller et al, 2009). 3) The ability of OMPH to reduce ADHD symptoms, but not desire to smoke, among whites could signal the presence of pharmacogenetic features, possibly more common among whites, that allow for a response of the ADHD but not of nicotine dependence; by contrast, pharmacogenetic features similarly responsive to ADHD and nicotine dependence could be more common among non-whites.

The use of racial/ethnic information to guide treatment selection has been a clinical tool in many areas of medicine. Treatment by race/ethnicity interactions might be driven by factors that are pharmacogenetic, cultural, or individual. Elucidating these factors will be important in reaching the goal of personalized medicine. It may be that OROS-MPH is an effective smoking cessation treatment for a subset of smokers. More work is needed to understand who they are, and how to select them.

Footnotes

Trial Registration Number: NCT00253747 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adler L, Cohen J. Diagnosis and evaluation of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2004;27:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1991. (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- Arnold LE, Elliot M, Sachs L, Bird H, Kraemer HC, Wells KC, Abikoff HB, Carda A, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, Hechtman L, Hindshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wigal T. Effects of ethnicity on treatment attendance, stimulant response/dose, and 14-month outcome in ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:713–27. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK, Levin ED, Sparrow E, Hinton SC, Erhardt D, Meck WH, Rose JE, March J. Nicotine and attention in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Botello-Harbaum M, Glassman AH, Masmela J, LoDuca C, Salzman V, Fried J. Smokers’ response to combination bupropion, nicotine patch, and counseling treatment by race/ethnicity. Ethn Dis. 2008;18:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cropsey KL, Weaver MF, Eldridge GD, Villalobos GC, Best AM, Stitzer ML. Differential success rates in racial groups: Results of a clinical trial of smoking cessation among female prisoners. Nicotine Tob Research. 2009;11:690–697. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Etter J, Hughes J. A comparison of the psychometric properties of three cigarette withdrawal scales. Addiction. 2006;101:362–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Becker C, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Frieden TR, Liu SY, Matte TD, Mostashari F, Deitcher DR, Cummings KM, Chang C, Bauer U, Bassett MT. Effectiveness of a large-scale distribution programme of free nicotine patches: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2005;365:1849–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66615-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TW, Nigg JT, Miller RL. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in African American children: What can be concluded from the past ten years? Clin. Psychol Review. 2008;29:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten R, editors. Techniques to Assess Alcohol Consumption. New Jersey: Humana Press, Inc; 1992. pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Newcorn J, Telang F, Solanto MV, Fowler JS, Logan J, Ma Y, Schulz K, Pradhan K, Wong C, Swanson JM. Depressed dopamine activity in caudate and preliminary evidence of limbic involvement in adults with attention-eficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:932–940. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhusen T, Somoza E, Brigham GS, Liu D, Green CA, Covey LS, Croghan IT, Adler LA, Weiss RD, Leimberger JD, Lewis DF, Dorer EM. Does treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) enhance response to smoking cessation intervention in ADHD smokers? A randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05089gry. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]