Abstract

The ability to predict tumor sensitivity toward radiotherapy may significantly impact the selection of patients for preoperative combined-modality therapy. The aim of the present study was to test the predictive value of Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) in rectal cancer patients and to investigate whether PLK1 plays a direct role in mediating radiation sensitivity. PLK1 expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry (n = 76) or Affymetrix HG133 microarray (n = 20) on pretreatment biopsies of patients with advanced rectal cancer. Expression was correlated with both tumor regression in the resected specimen and long-term clinical outcome. Furthermore, we used small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to down-regulate PLK1 expression in colorectal cancer cells and analyzed the effects of PLK1-specific siRNAs by Western blot and quantitative real-time PCR analysis, FACScan analysis, caspase 3/7 assays, and colony-forming assays. We observed that increased PLK1 protein expression was significantly related to a poorer tumor regression and a higher risk of local recurrence in uni- and multivariate analysis. A significant decrease of PLK1 expression by siRNAs in combination with ionizing radiation induced an increased percentage of apoptotic cells and increased caspase 3/7 activity. Furthermore, enhanced G2-M levels, decreased cellular viability, and reduced clonogenic survival were demonstrated, indicating a radiosensitizing effect of PLK1 depletion. Therefore, PLK1 may be a novel predictive marker for radiation response as well as a promising therapeutic target in rectal cancer patients.

Recent data from preoperative radiochemotherapy (RCT) in rectal cancer indicate a broad variety in tumor responses, ranging from pathological complete response with no viable tumor cells left to virtually no tumor regression at all.1 Despite uniform treatment protocols, this observed heterogeneity in treatment response is most probably caused by the individual genetic accouterment of the tumor. Current research has focused on molecular markers involved in the resistance toward anticancer therapy including key elements of the apoptotic and mitotic pathways.2,3 Among these factors, the serine/threonine kinase Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) has emerged as prognostic factor and as promising target for cancer therapy,4,5 because it is a key regulator for the mitotic progression of mammalian cells,6,7,8 and it is overexpressed in all human cancers analyzed up to date.9,10,11,12 Several preclinical approaches including the use of PLK1 antibodies, dominant-negative forms of PLK1, antisense oligonucleotides, small interfering RNA (siRNA) and small molecule inhibitors have consistently revealed cell cycle arrest at G2-M, and inhibition of tumor proliferation both in vitro and in vivo associated with the induction of apoptosis.13,14,15,16,17,18,19 A growing number of small molecule inhibitors is currently under clinical investigation.20,21,22,23,24

PLK1 kinase activity is inhibited by DNA damaging agents, in an ataxia telangiectasia mutated or Rad3-related kinase-dependent manner.25,26,27 The inhibition of PLK1 following DNA damage blocks the activation of Cdk1/cyclin B complexes by the Cdc25C phosphatase. The expression of a constitutively active mutant PLK1 can override the G2 cell cycle arrest following DNA damage and thus counteracts the fidelity of genomic information.25 Elevated PLK1 activity compensates at least in part the requirement for Aurora A in checkpoint recovery.28 Still, the role of PLK1 in the context of a DNA-damaging clinical treatment of cancer patients has not been elucidated yet.

In this study we analyzed the correlation of PLK1 expression in pretreatment tumor material of 76 rectal cancer patients, and the efficacy of preoperative RCT.29,30 To evaluate the role of PLK1 for radiation response, we determined the effects of down-regulation of PLK1 expression using siRNAs on the response of colorectal carcinoma cells toward ionizing radiation in a cell culture-based model system.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and siRNAs

Monoclonal anti-PLK1, anti-Cyclin B1, anti-p38, goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany), anti-poly-adenosyl-ribose-polymerase (PARP) antibody from Cell Signaling Technologies (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt/Main, Germany). PLK1-specific and control siRNAs were used as described previously.17,31

Cell Culture and Irradiation Procedure

We selected two p53-defective colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT-15, HT-29).32 The HCT-15 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (LGC Promochem, Wiesbaden, Germany), and HT-29 cells were from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. Fetal calf serum was from PAA Laboratories (Coelbe, Germany), RPMI 1640, PBS, Opti-MEM I, oligofectamine, glutamine, and trypsin from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany). Cells were irradiated at room temperature with a single dose of 2 or 8 Gy using a linear accelerator (SL 75/5; Elekta, Crawley, UK) with 6 megaelectron volt (MEV) photons/100 cm focus–surface distance with a dose rate of 4.0 Gy/min.

siRNA Treatment of Cancer Cells

Cells were treated with siRNAs or with irradiation 1 day after subculturing. For combinatorial studies, cells were transfected 1 hour after irradiation with the PLK1-specific and scrambled control siRNA (56 pM to 5.6 nmol/L) using the oligofectamine protocol (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe Germany) as described previously.17 Cell culture studies were done in triplicate for each time point.

Western Blot Analyses

For Western blot analyses cells were lysed 6 to 72 hours after irradiation and transfection and protein concentration was determined as described previously.17 Total protein (50 μg) was separated on 10% Bis-Tris-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) with subsequent antibody incubation as described previously.33

Quantitative PLK1 TaqMan PCR

Total RNA from cultured cells was isolated using RNeasy minikits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and transcribed into cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Thereafter, 50 ng of cDNA were subjected to quantitative real-time PCR analyses targeting PLK1 and GAPDH as described previously.34

Quantification of Apoptosis and Caspase 3/7 Assay

For the quantification of apoptotic tumor cells, FITC-labeled recombinant chicken AnnexinV (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in combination with propidium iodide to discriminate necrotic cells was used. In brief, 105 cells were resuspended in 500 μl of Ringer solution, incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark with 1 μg/ml AxV-FITC/1 μg/ml propidium iodide, and subsequently analyzed by a BD Biosciences FACScan apparatus (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Caspase 3/7 activity was measured in a 96-well microplate format as described previously.34

3-(4,5-methylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- Diphenyl-Tetrazolium Bromide Assay

Cells transfected with siRNAs were seeded in 96-well microplates, grown for 24 hours, and subsequently exposed to irradiation. 3-(4,5-methylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide assays were performed as described previously.35

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cell cycle distribution was analyzed using a FACScan apparatus (BD Biosciences). For FACScan analysis, cells were harvested, washed with PBS, fixed and stained as described previously.33 Quantification was done using ModFit LT 3.2 for MAC (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME). At least three independent experiments were done for each set of data.

Clonogenic Survival Assay

The clonogenic assay was done on single cell suspension as described previously.29 Calculation of survival fractions (SFs) was done using the equation SF = colonies counted/cells seeded × (PE/100), taking into consideration the individual plating efficiency (PE). Survival parameters α and β were fitted according to the linear quadratic equation SF = exp [−α × D − β × D2] with D = dose using TechPlot software (Techplot, Braunschweig, Germany).

Preoperative RCT Protocol and Biopsy Samples

A cohort of 76 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer (International Union against Cancer stage II and III) received preoperative RCT within a prospective protocol (XELOX-RT), as previously described in more detail.29,30 Patient and tumor characteristics are given in Table 1. Patients received a total dose of 50.4 Gy with daily fractions of 1.8 Gy on 5 consecutive days per week. Concomitant chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin was administered on days 1 to 14 and 22 to 35. Six weeks after completion of RCT, patients underwent surgery. Four cycles of adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin were scheduled. Patients were followed at 3-month intervals for 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. Proctoscopy (if rectum was in place) was performed at 6 months intervals in the first year, and once per year thereafter. A follow-up schedule for abdominal ultrasound, computerized tomography of the abdomen and pelvis, and chest x-rays was performed. Histological confirmation of locoregional and distant relapse was encouraged. Alternate acceptable criteria included sequential enlargement of a mass in radiological studies. Median follow-up for all patients was 42.5 (range, 4.5 to 98) months.

Table 1.

Plk1 Staining Intensity, Percentage of Positive Tumor Cells, and Weighted Score in Rectal Cancer Biopsy Specimen

| Staining intensity | % of positive tumor cells | Weighted score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weak | 28 (36.8%) | 5–25% | 23 (30.3%) | 0–3 | 31 (40.7%) |

| Moderate | 30 (39.5%) | 26–50% | 15 (19.7%) | 4–6 | 26 (34.3%) |

| Intense | 18 (23.7%) | 51–75% | 28 (36.8%) | 7–9 | 10 (13.2%) |

| >75% | 10 (13.2%) | 12 | 9 (11.8%) | ||

Archival paraffin-embedded biopsy tumor specimens were available for all 76 patients. Additionally, fresh biopsies of the tumor and corresponding normal tissue were prospectively collected from 20 of these 76 patients, immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored until extraction of mRNA after removal of portions needed for pathological diagnosis to ensure that tumor specimen contained >60% tumor cells.

Microarray Expression Analysis

Ten micrograms of total RNA were used to prepare biotinylated cRNAs. Hybridization of 15 mg labeled cRNA was done on HG-U133A Affymetrix microarrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as described previously.36 All arrays were globally scaled to a target value of 1000, and intracellular PLK1 mRNA values (Affymetrix Average Difference Units) were derived using Microarray Suite 5.0 software.

Histochemical Staining for PLK1 and Scoring

Deparaffinized tissue-sections were stained for PLK1 as described previously.37 For scoring purpose, the percentage of positive tumor cells was assigned to one of the following categories: 0 (<5%), 1 (5 to 25%), 2 (26 to 50%), 3 (51 to 75%), and 4 (>75%). The intensity of PLK1 immunostaining was scored as: 1+ (weak), 2+ (moderate), and 3+ (intense). The percentage of positive tumor cells and staining intensity were then multiplied to produce a weighted score of 0 to 12.

Histopathological Assessment of Response to RCT

Tumor regression grading (TRG) of the resected tumor was semiquantitatively determined according to Dworak et al,38 ranging from TRG 4 when no viable tumor cells were detected, to TRG 0 when fibrosis was completely absent. TRG 3 was defined as regression >50% with fibrosis outgrowing the tumor mass, TRG 2 was defined as regression <50%, and TRG 1 was defined basically as a morphologically unaltered tumor mass.

Statistical Methods

Significance of differences in tumor and mucosal intracellular PLK1 mRNA values were evaluated by the Student’s t-test. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to analyze a correlation between PLK1 mRNA expression and histochemical PLK1 weighted scores. For the association of PLK1 weighted score with histopathological tumor response (<50% tumor regression vs ≥50% tumor regression) in the resected specimen after preoperative RCT, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used. Because of the limited number of patients in our study and to facilitate further statistical analysis, the weighted PLK1 score (0 to 12) was arbitrarily dichotomized: a score of <6 was classified as “low PLK1 expression,” and a score of ≥6 was classified as “high PLK1 expression.” The association of this dichotomized variable with other pretherapeutical clinicopathologic factors was tested by the use of Fisher’s exact test or χ2 analysis. Survival and recurrence rates were calculated using the method of Kaplan-Meier, and differences between dichotomized PLK1 expression levels were analyzed with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard models, controlling for sex, T-, N-, and M-category, and grading, were also conducted to assess the hazard ratio in survival and recurrence rates between patients with high and low PLK1 expressing tumors.

Experimental in vitro data are presented as mean ± SDs from three or more independent experiments. Two-way analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was done to consider random effects of individual gels and different siRNA treatments. For two-way ANOVAs, all treatment groups were compared with control cells. All P values are two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PLK1 Is Overexpressed in Rectal Tumor Tissue Compared with Normal Mucosa

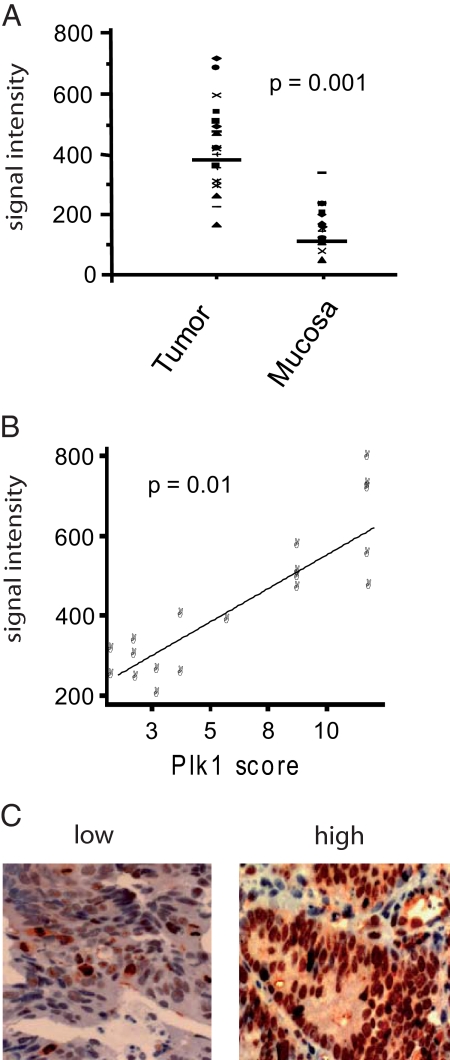

First, we analyzed the PLK1 mRNA expression in tumor biopsies versus normal rectal mucosa tissue in 20 consecutive patients by HGU133 Affymetrix microarray analysis.1,29,30 A significantly increased median intracellular mRNA level was observed in tumor biopsies compared with normal mucosa: 459 ± 146 Affymetrix Average Difference Units versus 150 ± 63 (P = 0.0001) (Figure 1A). Levels of intracellular PLK1 mRNA in tumor tissue correlated significantly (KK = 0745, P = 0.01) with the levels of histochemically detected protein expression in the same tumor biopsy specimen (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

PLK1 expression in rectal cancer biopsies. A: PLK1 mRNA levels in pretreatment tumor biopsies and adjacent noncancerous mucosa of 20 patients assayed by Affymetrix HGU133 microarrays. B: Correlation of the PLK1 mRNA levels in 20 patients to the immunohistochemically determined protein expression (labeling score: % positive tumor cells × staining intensity) in the corresponding tumor biopsies (KK = 0.745, P = 0.01). C: Examples of rectal cancer specimens with low or intense immunohistochemical staining of PLK1 in tumor cells (original magnification ×20).

PLK1 Is a Predictor for Tumor Regression and Local Tumor Control After Preoperative RCT and Surgical Resection

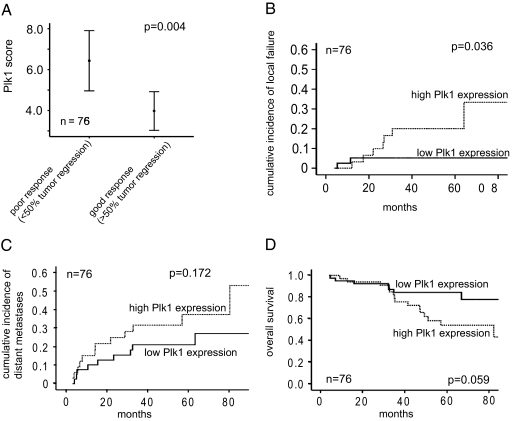

To analyze the correlation between PLK1 protein levels and tumor regression in the resected specimen as well as long-term clinical outcome following RCT and surgical resection we studied an enlarged cohort of 76 rectal cancer patients. PLK1 protein staining was homogeneous within a patient′s tumor biopsy, but varied considerably among tumors (Figure 1C). Staining intensity, percentage of positive tumor cells, and the resulting weighted score for all 76 patients is given in Table 1. As depicted in Figure 2A, the PLK1 weighted score was significantly correlated with the histopathologically determined tumor regression in the resected specimen after RCT: the mean score was significantly higher in tumors showing poor response (<50% tumor regression) compared with good response (≥50% tumor regression): 6.43 ± 4.03 vs 3.98 ± 3.17, P = 0.004). No association of the weighted PLK1 score with other clinicopathologic factors was noted (Table 2).

Figure 2.

PLK1 as a predictor for tumor regression and local control after preoperative RCT. A: Association of PLK1 labeling score with categorized TRG on surgical specimens (n = 76) of patients with rectal cancer treated with preoperative RCT. The dot represents the median value. B: Cumulative incidence plot of local failure, distant metastases (C), and overall survival (D) according to a high PLK1 or low PLK1 expression. Data are based on immunohistochemical evaluation of pretreatment biopsies.

Table 2.

Association of Plk1 Expression with Pretreatment Clinicopathologic Factors in 76 Patients with Rectal Cancer

| Factor | N | Low Plk1 expression | High Plk1 expression | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 76 | 41 (54%) | 35 (46%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 57 | 30 (53%) | 27 (47%) | 0.79 |

| Female | 19 | 11 (58%) | 8 (42%) | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤median | 38 | 24 (63%) | 14 (37%) | 0.29 |

| median | 38 | 18 (47%) | 20 (53%) | |

| T category | ||||

| cT3 | 60 | 31 (52%) | 29 (48%) | 0.44 |

| cT4 | 16 | 10 (63%) | 6 (37%) | |

| N category | ||||

| cN0 | 21 | 10 (48%) | 11 (52%) | 0.41 |

| cN+ | 55 | 32 (58%) | 23 (42%) | |

| M category | ||||

| cM0 | 71 | 40 (56%) | 31(44%) | 0.12 |

| cM1 | 5 | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | |

| Grading | ||||

| G1-G2 | 62 | 32 (52%) | 30 (48%) | 0.39 |

| G3 | 14 | 9 (64%) | 5 (36%) |

Data are based on immunohistochemical evaluation of pretreatment biopsies.

With a median follow-up of 42.4 months (range, 4.5 to 98 months), 9 of 76 patients developed a local tumor relapse. “High” PLK1 protein expression was significantly related to an increased risk of local recurrence (5-year cumulative incidence: 20%, 95% confidence interval, 6 to 34%) compared with tumors showing “low” PLK1 expression” (5.2%, 95% confidence interval, 0 to 12%, P = 0.036) (Figure 2B). Indeed, six of the nine local recurrences exhibited the highest PLK1 weighted score 12 in the tumor biopsy before treatment. Cox proportional hazard models were further used to control for sex, T-, N-, and M-category, and grading. Patients with “high PLK1 expression” remained at greater risk for local tumor relapse, with a hazard ratio of 6.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 26.5, P = 0.04). Hazard ratios for sex, T-, N-, and M-category, and grading were 4.7 (P = 0.18), 4.0 (P = 0.09), 0.93 (P = 0.93), 1.14 (P = 0.91), and 0.95 (P = 0.94), respectively.

Conversely, PLK1 expression had no statistically significant impact on the cumulative incidence of distant metastases (5-year rate 37 versus 21% for high and low PLK1 expression, respectively, P = 0.17) (Figure 2C). High PLK1 expression was associated with a nonsignificant trend for reduced overall survival (5-year rate 54.2 versus 84.4%, for high and low PLK1 expression, respectively, P = 0.059) (Figure 2D).

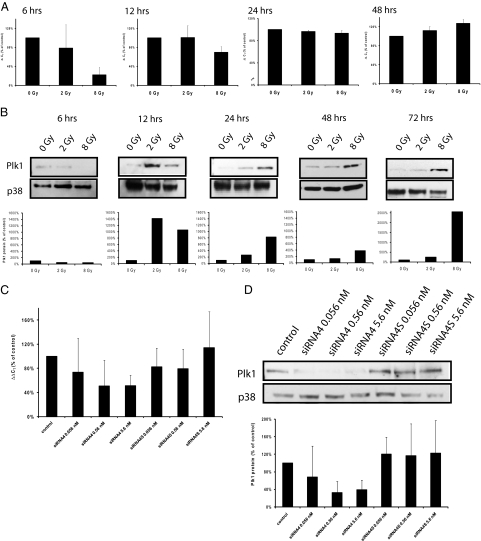

Irradiation Influences PLK1 Expression in a Time-and Dose-Dependent Manner

This critical correlation of PLK1 levels in primary tumors with reduced response to RCT, and with a higher risk of local recurrence prompted us to evaluate the role of PLK1 for the recovery of cells from irradiation, because previous experiments demonstrated elevated levels of PLK1 activity can override the DNA damage-induced checkpoint.25 Thus, we determined first whether PLK1 expression in HCT-15 cells is modulated 6 to 72 hours after ionizing irradiation with 2 and 8 Gy using quantitative real-time and Western blot analyses (Figure 3). Six and 12 hours after irradiation, PLK1 mRNA was reduced statistically significantly compared with untreated controls (Figure 3A; P = 0.0127 for 8 Gy after 6 hours, P = 0.049 for 8 Gy after 12 hours). Starting 24 hours after irradiation, PLK1 mRNA increased in a dose-dependent manner, which was statistically significantly after 48 hours for 2 and 8 Gy (2 Gy: P = 0.016, 8 Gy: P < 0.001). PLK1 protein levels were reduced 6 hours after irradiation (P = 0.0023 for 2 Gy, P = 0.0069 for 8 Gy), at 12 to 72 hours after irradiation PLK1 protein was elevated in a dose-dependent manner, starting with an increase of PLK1 protein 12 hours after irradiation with 2 Gy (P < 0.0001 for 2 and 8 Gy) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of PLK1 expression in HCT-15 colorectal cells after irradiation and after transfection with PLK1-specific siRNAs. Total mRNA was extracted at 6 to 48 hours after irradiation with 0, 2, and 8 Gy, and PLK1 mRNA expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (A). Shown are the relative mRNA levels of PLK1 in reference to GAPDH expression. B: Western blot analysis from total cellular proteins extracted 6 to 72 hours after irradiation using antibodies against PLK1 and p38 as a loading control. Figure shows representative blots and graphical summary of three independent experiments (mean ± SD). C: Total RNA was extracted 24 hours after transfection, and PLK1 mRNA was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Shown are the relative mRNA levels of PLK1 in reference to GAPDH expression. D: Western blot analysis from total cellular proteins extracted 48 hours after transfection using antibodies against PLK1 and p38 as a loading control. C and D show representative blots and graphical summary of three independent experiments (mean ± SD).

PLK1-Specific siRNAs Down-Regulate PLK1 Expression in Untreated and Irradiated Colorectal Cancer Cells

To analyze the effect of PLK1-specific siRNAs in HCT-15 cells, we determined PLK1 mRNA (after 24 hours) and protein expression (after 48 hours). As compared with untransfected controls, transfection with either 0.056 nmol/L, 0.56 nmol/L or 5.6 nmol/L siRNA4 reduced PLK1 mRNA expression in HCT-15 cells (Figure 3C; 0.056 nmol/L reduction to 74%, P = 0.35, 0.56 nmol/L to 51%, P = 0.06, 5.6 nmol/L to 51%, P = 0.0032). Transfection with siRNA4S, a scrambled version of siRNA4, did not alter PLK1 expression (Figure 3C), indicating a specific knock-down of PLK1. To analyze, whether the down-regulation of PLK1 mRNA was accompanied by reduced PLK1 protein, we did Western blot analyses 48 hours after transfection, and detected significantly reduced PLK1 protein after transfection with 0.56 and 5.6 nmol/L siRNA4 (Figure 3D; 0.56 nmol/L reduction to 32%, P = 0.047, 5.6 nmol/L to 38%, P = 0.045).

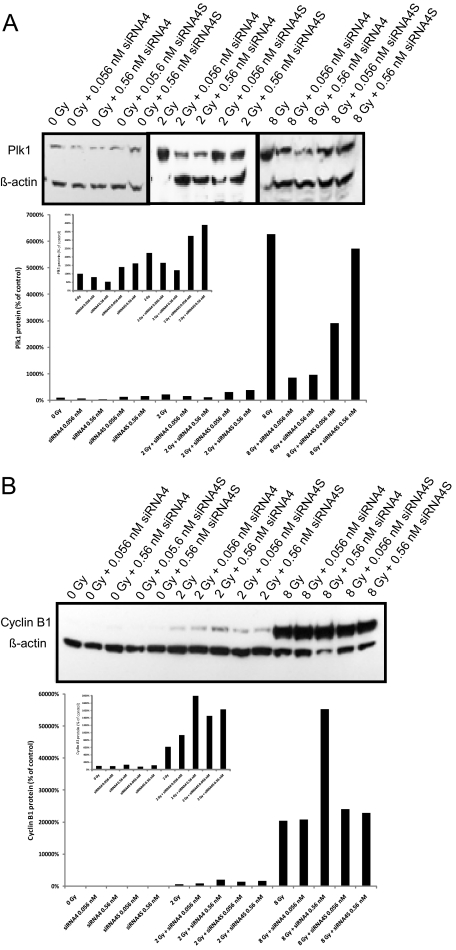

To find out whether siRNA4 is also suited to reduce PLK1 expression in irradiated cells, quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analyses were done 48 and 72 hours after treatment of HCT-15 cells (irradiation followed by transfection 1 hour later). We detected significantly reduced PLK1 mRNA levels after single administration of 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4 (P = 0.0035). While PLK1 expression increases with elevated irradiation doses, the combination of irradiation with siRNA4 reduces PLK1 mRNA expression compared with the respective irradiation dose alone (0.56 nmol/L siRNA + 8 Gy compared with 8 Gy alone: P = 0.014; data not shown). This reduction of PLK1 mRNA compared with irradiated control cells (0, 2, or 8 Gy, respectively) was associated with reduced PLK1 protein expression (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

PLK1 and cyclin B1 protein expression after combinatorial treatment. PLK1 protein in HCT-15 colorectal cancer cells following irradiation combined with siRNA4 transfection (0.056, 0.56, and 5.6 nmol/L). A: Western blot analysis from total cellular protein extracted 72 hours after treatment using antibodies against PLK1 and ß-actin as a loading control. Figure shows representative blots and graphical summary of three independent experiments (mean ± SD). B: Western blot analysis from total cellular protein extracted 72 hours after treatment using antibodies against cyclin B1 and β-actin as a loading control. Figure shows representative blots and graphical summary of three independent experiments. The smaller graphs within the figure shows enlarged graphs of PLK1 (A) or cyclin B1 (B) expression after the combination of 0 and 2 Gy with siRNAs.

PLK1 activity has been described to be required for degradation of cyclin B1 via the Anaphase Promoting Complex (APC) and exit from mitosis.6,39,40,41 As both treatments (siRNA-based depletion and DNA damage induced by irradiation) are expected to inhibit PLK1 activity, we investigated whether these treatments block exit from mitosis as indicated by elevated levels of cyclin B1. The increase of cyclin B1 protein after transfection of HCT-15 cells with siRNA4 alone was weak in non-synchronized cells. Increasing doses of irradiation (2 or 8 Gy) lead to a strong cellular enrichment of cyclin B1. Remarkably, the combinatorial treatment of 8 Gy together with 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4 induced the strongest effect on cyclin B1 stabilization compared with untreated control cells (Figure 4B).

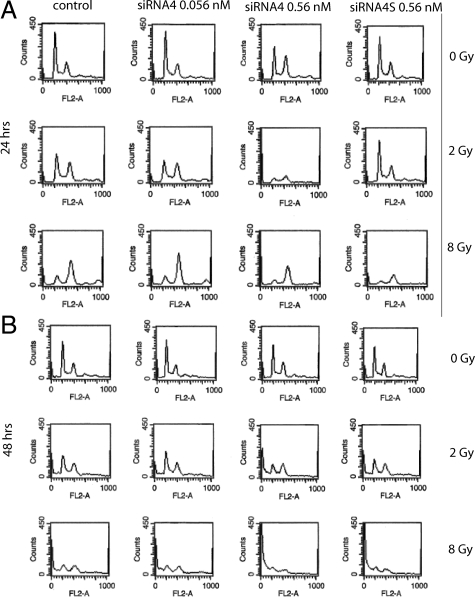

G2-M Arrest after Treatment with PLK1-Specific siRNAs and Irradiation Alone or in Combination

To verify whether elevated levels of cyclin B1 reflect an arrest of cells in mitosis, HCT-15 cells were monitored by FACScan analysis after combinatorial treatment. While 24 hours after treatment 0.056 nmol/L siRNA4 alone did not influence cell cycle distribution (22.50% G2-M phase versus 23.65% in control cells, Figure 5A, upper line, second panel), 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4 induced a strong G2-M arrest (36.93%; Figure 5A, upper line, third panel). Irradiation (2 Gy) before transfection enhanced the siRNA4-specific effects: control cells and cells treated with 0.056 nmol/L siRNA4 showed an elevated number of cells in G2-M phase (control cells (2 Gy alone): 33.81%, 0.056 nmol/L siRNA4 37.27%), and 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4 together with 2 Gy led to a strong G2/M phase arrest of 55.47% (Figure 5, second line, third panel). Irradiation with 8 Gy before transfection induced a strong G2-M arrest for all treatments (control cells (8Gy): 63.97%, 0.056 nmol/L siRNA4: 69.70%, 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4: 71.20%, and 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4S: 55.04%; Figure 5A, third line). siRNA4S did not alter cell cycle distribution significantly compared with control cells after irradiation alone.

Figure 5.

Effect of radiation and PLK1 siRNA transfection on cell cycle distribution of HCT-15 cells. HCT-15 cells were irradiated and transfected with siRNA4 and siRNA4S, respectively. FACScan analyses were done 24 hours (A) and 48 hours (B) after transfection. The graphs show the absolute number of cells in the respective cell cycle phases. Left peak represents cells in G0-G1 phase, and right peak represents cells in G2-M phase, the sub-G0-G1 peak can be detected left from the G0-G1 peak.

48 hours after irradiation and transfection we observed an elevated number of cells in G2/M phase (increase from 14.10% with 0 Gy to 20.97% with 0 Gy + 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4, from 24.84% with 2 Gy to 28.71% with 2 Gy + 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4, and from 35.68% with 8 Gy to 45.28% with 8 Gy + 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4; Figure 5B). Taken together, a synergistic elevation of cells in G2/M phase after the combination of irradiation with depletion of PLK1 was detected (especially using the combinations of 0.056 nmol/L siRNA4 together with 2 Gy, and using 0.56 nmol/L siRNA4 together with 8 Gy). While 48 hours after irradiation and transfection an elevated percentage of cells was found as sub-G0-G1 peak (Figure 5B), after 72 hours the majority of the cells were found in sub-G0-G1 (data not shown) indicating that the percentage of apoptotic cells increases with time.

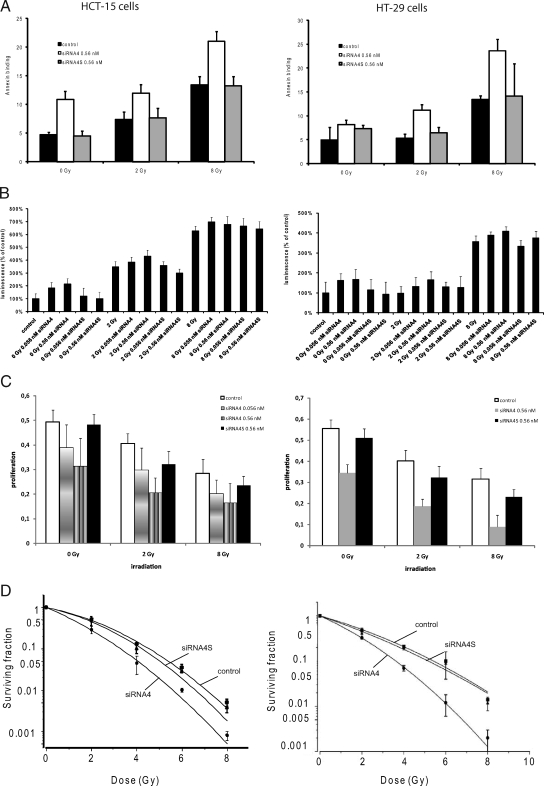

PLK1 Depletion Radiosensitizes Human Colorectal Cancer

To analyze this apoptotic effect in more detail, we did Annexin binding and caspase 3/7 assays after combinatorial treatment. Annexin V binding assays revealed after 48 hours significantly higher spontaneous and radiation-induced apoptosis in siRNA4-treated HCT-15 cells, shown by a 2.3-fold increase of AxV-positive cells compared with control or siRNA4S-treated cells for 0 Gy (P = 0.0009; Figure 6A, left panel). After irradiation with 2 Gy and subsequent transfection cells showed a 1.6fold increase in AxV-positive cells compared with controls (P = 0.0001), and using 8 Gy in combination with siRNA4 treatment the increase was 1.6-fold (P = 0.003). HT-29 cells showed a similar response in Annexin V binding assays (Figure 6A, right panel). siRNA4 induced a significant increase in AxV-positive HT-29 cells compared with controls (P = 0.003). After combinatorial treatment the increase in AxV-positive cells was approximately twofold (P = 0.002 for 2 Gy and P = 0.01 for 8 Gy).

Figure 6.

Apoptosis induction after the combination of irradiation and PLK1 inhibition in HCT-15 and HT-29 cells. A: AnnexinV staining 48 hours after combinatorial treatment (mean ± SD). B: Graphical summary of caspase 3/7 activation 72 hours after combinatorial treatment. Luminescence is given as relative light unit levels (mean ± SD). C: 3-(4,5-methylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide assay after combinatorial treatment. D: Clonogenic survival of HCT-15 and HT-29 cells transfected with either 5.6 nmol/L siRNA4 or siRNA4S. Nontreated cells served as a control. After 12 to 14 days, colonies >50 cells were counted, and survival curves with SFs normalized to the plating efficiency were fitted according to the linear quadratic equation. Data are displayed as the mean ± SD from three experiments.

Caspase 3/7 activation could be shown after transfection of HCT-15 cells with siRNA4 alone (Figure 6B, left panel; 0.056 nmol/L activation to 171%, P < 0.0001, 0.56 nmol/L activation to 260%, P < 0.0001). This activation could be enhanced with irradiation of 2 Gy before transfection (2 Gy + 0.056 nmol/L activation to 425% compared with 0 Gy, P = 0.028 compared with 2 Gy alone, 2 Gy + 0.56 nmol/L to 374% compared with 0 Gy, P = 0.2 compared with 2 Gy alone). The co-treatment of HT-29 cells induced synergistic effects as previously obtained with HCT-15 cells (Figure 6B, right panel, 0.056 nmol/L siRNA4 activation to 167%, P = 0.049, 0.56 nmol/L to 185%, P = 0.043, 2 Gy + 0.056 nmol/L to 155%, P = 0.03 compared with 0 Gy, P = 0.01 compared with 2 Gy, 2 Gy + 0.56 nmol/L to 182%, P = 0.009 compared with 0 Gy, P = 0.004 to 2 Gy). The combinatorial treatment did not induce further activation of caspase 3/7 in both cell lines compared with irradiation with 8 Gy alone.

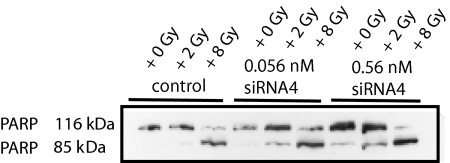

Apoptosis was confirmed by PARP cleavage after irradiation followed by transfection with siRNA4 (Figure 7). As demonstrated for the caspase 3/7 activation, 8 Gy resulted in massive cell death associated with complete PARP cleavage, but the lower dose of 2 Gy showed an elevation of apoptosis after the combination with siRNA4 indicating a radiosensitizing effect of PLK1 knockdown.

Figure 7.

Apoptosis induction after combinatorial treatment in HCT-15 cells. Western blot analysis from total cellular protein extracted 72 hours after irradiation and transfection using antibodies against PARP demonstrating PARP cleavage in HCT-15 cells. Figure shows a representative blot.

To further investigate cell viability and proliferation in PLK1-depleted and irradiated HCT-15 and HT-29 cells, metabolic activity was analyzed by the 3-(4,5-methylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide assay. Treatment with irradiation together with siRNA4 resulted in a significant reduction of HCT-15 cell viability (Figure 6C, left panel; P < 0.0001 for 0, 2, and 8 Gy) and of HT-29 cell viability (Figure 6C, right panel; P = 0.02 for 0 Gy, P = 0.002 for 2 Gy, P = 0.02 for 8 Gy) compared with controls for 0, 2, and 8 Gy. Taken together, the down-regulation of PLK1 following a DNA-damaging treatment impairs the proliferative activity of colon cancer cells significantly.

To further investigate the radiosensitizing ability of siRNA4, as observed for the induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, clonogenic survival assays were done after treatment with siRNA4 combined with ionizing radiation. The clonogenic survival of HCT-15 and HT-29 cells after irradiation with 2 to 8 Gy, either treated with siRNA4 (0.56 nmol/L) or siRNA4S, was compared with untreated control cells. As displayed in Figure 6D, inhibition of PLK1 shifted the survival curves down for HCT-15 (left panel) and HT-29 cells (right panel) with a reduction in the shoulder. In both cell lines, 50% survival were significantly reduced (P = 0.03) in siRNA4-treated cells, resulting in a calculated radiation-induced cytotoxicity enhancement factor of 1.79 for HCT-15 and of 1.57 for HT-29 cells (Table 3).

Table 3.

Radiation Response Parameters of HCT-15 and HT-29 Colorectal Cells Nontreated or Transfected with Plk1-Specific siRNA

| PE (%) | α (Gy−1) | β (Gy−2) | LD50 (Gy) | Radiation-induced cytotoxicity enhancement factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT-15 | |||||

| control | 32.7 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 2.15 ± 0.09 | 1.79 ± 0.06 |

| + siRNA4 | 21.0 | 0.64 ± 0.07 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 1.20 ± 0.01 | |

| HT-29 | |||||

| control | 26.8 | 0.29 ± 0.05 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 2.09 ± 0.03 | 1.57 ± 0.02 |

| + siRNA4 | 15.7 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.005 | 1.33 ± 0.01 |

Radiation-induced cytotoxicity enhancement factors at 50% survival (LD50) were calculated by transforming the linear quadratic equation (SF = exp [−α × D − β × D2]) using α and β values of the individual survival curves.

Discussion

Here we report that PLK1 is over-expressed at both the transcriptional and protein level in rectal cancer specimens as compared with normal rectal mucosa. For patients uniformly treated with a neoadjuvant RCT protocol, a higher PLK1 expression was significantly associated with poor tumor regression, and a higher likelihood of local recurrence indicating that tumor cells overexpressing PLK1 exhibit a more radioresistant phenotype. While numerous reports describe the prognostic value of PLK1 in a variety of human cancers,9,10,11 this is the first report describing the value of PLK1 expression for rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative RCT and surgical resection.

Given this evidence implicating the level of PLK1 as critical risk factor correlating with the malignant potential and resistance of colorectal cancer toward DNA-damaging anticancer therapy, we further investigated whether PLK1 plays a direct role in mediating radiation resistance. Recent reports pointed out that the overexpression of PLK1 overrides a DNA damage induced checkpoint arrest.25,26 Still, it has not been investigated yet whether the inhibition of PLK1 by exogenous agents helps to prevent the recovery of cancer cells from a DNA damage-induced cell cycle arrest. In particular, the role of PLK1 for the radiosensitization of cancer cells has not been explored yet. Because our analysis suggests that PLK1 levels are critical determinants for local recurrence following RCT in primary rectal cancer, we tested the hypothesis whether the inhibition of PLK1 is suitable to prevent the re-entry of cancer cells into the cell cycle again following RCT. For this purpose, we studied the impact of PLK1-specific siRNAs alone or in combination with ionizing radiation on HCT-15 cells as novel and effective molecular targeted anti-cancer regimens. We observed synergistic effects using low siRNA4 concentrations (0.056 or 0.56 nmol/L, respectively, with 8 Gy) on tumor cell proliferation, G2-M cell cycle arrest, induction of apoptosis, and finally an increased radiation sensitivity as determined by a clonogenic survival assay. Our results highlight the critical role of PLK1 for the resumption of cancer cell proliferation after a checkpoint arrest.31,33

In the current study of PLK1 mRNA and protein expression in colorectal cancer cells we demonstrate that following an initial down-regulation levels increase in a dose-dependent manner at 24 and 48 hours postirradiation. A transient down-regulation of PLK1 mRNA following irradiation was also observed previously in MT-1 breast cancer cells.42 This and our observations support the role of PLK1 for cells to recover from DNA damage induced arrest.28,43 The fact that the overexpression of a PLK1 T210D mutant, which is constitutively active, can override the DNA damage-induced G2-M arrest suggests PLK1 as a critical component of the DNA damage checkpoint regulation.25 Thus, we hypothesize that after irradiation and down-regulation of PLK1, cells remain for a prolonged period of time in a G2-M arrest and in a more radio-responsive phase of the cell cycle. Depletion of PLK1 at the time point when the cells raise PLK1 expression disables the cells to resume cell cycle activity after DNA damage is repaired and may force increased cell death via apoptosis. This view is further strengthened by the increased proportion of cells in G2-M phase followed by increased apoptotic cell death. Because a recent report suggested Cdk1 and PLK1 kinases are critical for checkpoint adaptation in U2-OS osteosarcoma cells,44 our data might indicate that PLK1 inhibition in rectal cancer cells prevents the termination of DNA replication response, which eventually leads to the induction of apoptosis. Furthermore, the probability of cell death following irradiation is increased as proven by a reduced clonogenic survival.

p53, which is disrupted in >50% of human cancers, is of central importance for the cellular response to DNA damage and other cellular stresses. Therefore, normal functioning of p53 maintains genome stability and is a potent barrier to cancer. Its activation leads to the transactivation of target genes, induction of growth arrest or apoptosis depending on the severity of the damage in a specific cellular context. For the identification of targets in the p53-regulated pathways, a panel of matched colorectal cancer cell lines differing only in their endogenous TP53 status was recently generated by targeted homologous recombination.32 Remarkably, most of the up-regulated genes in cells without TP53 following DNA damage were elements of the G2-M and spindle assembly checkpoints. PLK1 as one of the up-regulated genes attracted the attention, because its inhibition in TP53−/− HCT116 cells led to a dramatic tumor inhibition in animal models. In our study we used two p53-defective cell lines, HT-29 and HCT-15, which should, according to the above described study be excellent candidates for a PLK1-targeted approach. We extend the results by Sur et al32 by showing that p53-deficient cells, which were irradiated with clinically relevant doses, are extremely vulnerable to the inhibition of PLK1 function.

In summary, our results suggest PLK1 as a predictive factor to identify patients likely to respond to preoperative RCT. In addition, targeting PLK1 in PLK1-overexpressing rectal tumors using novel small molecule inhibitors, like BI2536 or SBE13,19,20,21,45 is a promising strategy to increase the therapeutic ratio of radiotherapy for rectal cancer in future clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the technical assistance of Eva Hausmann, Elisabeth Kurunci-Csacsko, and Markus Knies.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Birgit Spänkuch, Ph.D., Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, or Franz Rödel, Ph.D., Department of Radiation Therapy and Oncology, Medical School, University of Frankfurt, Theodor-Stern-Kai 7, 60590 Frankfurt/Main, Germany. E-mail: Birgit.Spaenkuch@t-online.de or franz.roedel@kgu.de.

Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant SP 1092/1-2), Wilhelm-Sander-Stiftung, Deutsche Krebshilfe (grant 108651), and Messer-Stiftung, Held-und-Hecker-Nachlassstiftung.

References

- Rodel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, Fuzesi L, Klimpfinger M, Fietkau R, Liersch T, Hohenberger W, Raab R, Sauer R, Wittekind C. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8688–8696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FM, Reynolds JV, Miller N, Stephens RB, Kennedy MJ. Pathological and molecular predictors of the response of rectal cancer to neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadimi BM, Grade M, Difilippantonio MJ, Varma S, Simon R, Montagna C, Fuzesi L, Langer C, Becker H, Liersch T, Ried T. Effectiveness of gene expression profiling for response prediction of rectal adenocarcinomas to preoperative chemoradiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1826–1838. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckerdt F, Yuan J, Strebhardt K. Polo-like kinases and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:267–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strebhardt K, Ullrich A. Targeting Polo-like kinase 1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:321–330. doi: 10.1038/nrc1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover DM, Hagan IM, Tavares AA. Polo-like kinases: a team that plays throughout mitosis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3777–3787. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr FA, Sillje HH, Nigg EA. Polo-like kinases and the orchestration of cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambault V, Glover DM. Polo-like kinases: conservation and divergence in their functions and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahr A, Karn T, Solbach C, Seiter T, Strebhardt K, Holtrich U, Kaufmann M. Identification of high risk breast-cancer patients by gene expression profiling. Lancet. 2002;359:131–132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht R, Elez R, Oechler M, Solbach C, von Ilberg C, Strebhardt K. Prognostic significance of Polo-like kinase (PLK) expression in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2794–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Sano B, Nagata T, Kato H, Sugiyama Y, Kunieda K, Kimura M, Okano Y, Saji S. Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is overexpressed in primary colorectal cancers. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:148–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichert W, Kristiansen G, Winzer KJ, Schmidt M, Gekeler V, Noske A, Muller BM, Niesporek S, Dietel M, Denkert C. Polo-like kinase isoforms in breast cancer: expression patterns and prognostic implications. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:442–450. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-1212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane HA, Nigg EA. Antibody microinjection reveals an essential role for human Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) in the functional maturation of mitotic centrosomes. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1701–1713. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Erikson RL. Polo-like kinase (Plk)1 depletion induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5789–5794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031523100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell JP, Brown CE, Bisi JE, Neill SD. Dominant-negative Polo-like kinase 1 induces mitotic catastrophe independent of cdc25C function. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:615–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spankuch-Schmitt B, Wolf G, Solbach C, Loibl S, Knecht R, Stegmuller M, von Minckwitz G, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Downregulation of human Polo-like kinase activity by antisense oligonucleotides induces growth inhibition in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3162–3171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spankuch-Schmitt B, Bereiter-Hahn J, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Effect of RNA silencing of Polo-like kinase-1 (PLK1) on apoptosis and spindle formation in human cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1863–1877. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.24.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spankuch B, Matthess Y, Knecht R, Zimmer B, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Cancer inhibition in nude mice after systemic application of U6 promoter-driven short hairpin RNAs against PLK1. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:862–872. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppner S, Proschak E, Schneider G, Spankuch B. Identification and validation of a potent type II inhibitor of inactive Polo-like kinase 1. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1806–1809. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenart P, Petronczki M, Steegmaier M, Di FB, Lipp JJ, Hoffmann M, Rettig WJ, Kraut N, Peters JM. The small-molecule inhibitor BI 2536 reveals novel insights into mitotic roles of Polo-like kinase 1. Curr Biol. 2007;17:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegmaier M, Hoffmann M, Baum A, Lenart P, Petronczki M, Krssak M, Gurtler U, Garin-Chesa P, Lieb S, Quant J, Grauert M, Adolf GR, Kraut N, Peters JM, Rettig WJ. BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of Polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr Biol. 2007;17:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumireddy K, Reddy MV, Cosenza SC, Boominathan R, Baker SJ, Papathi N, Jiang J, Holland J, Reddy EP. ON01910, a non-ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor of PLK1, is a potent anticancer agent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes C, Mezna M, Fischer PM. Progress in the discovery of Polo-like kinase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:181–197. doi: 10.2174/1568026053507660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin AG, Bleam MR, Richter MC, Erskine SG, Kruger RG, Madden L, Hassler DF, Smith GK, Gontarek RR, Courtney MP, Sutton D, Diamond MA, Jackson JR, Laquerre SG. Distinct concentration-dependent effects of the Polo-like kinase 1-specific inhibitor GSK461364A, including differential effect on apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6969–6977. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits VA, Klompmaker R, Arnaud L, Rijksen G, Nigg EA, Medema RH. Polo-like kinase-1 is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:672–676. doi: 10.1038/35023629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vugt MA, Smits VA, Klompmaker R, Medema RH. Inhibition of Polo-like kinase-1 by DNA damage occurs in an ATM- or ATR- dependent fashion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41656–41660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101831200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ree AH, Bratland A, Solberg LK, Fodstad O. Ionizing radiation inhibits the PLK cell cycle gene in a G2 checkpoint-dependent manner. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macurek L, Lindqvist A, Lim D, Lampson MA, Klompmaker R, Freire R, Clouin C, Taylor SS, Yaffe MB, Medema RH. Polo-like kinase-1 is activated by aurora A to promote checkpoint recovery. Nature. 2008;455:119–123. doi: 10.1038/nature07185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodel C, Grabenbauer GG, Papadopoulos T, Hohenberger W, Schmoll HJ, Sauer R. Phase I/II trial of capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and radiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3098–3104. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodel C, Liersch T, Hermann RM, Arnold D, Reese T, Hipp M, Furst A, Schwella N, Bieker M, Hellmich G, Ewald H, Haier J, Lordick F, Flentje M, Sulberg H, Hohenberger W, Sauer R. Multicenter phase II trial of chemoradiation with oxaliplatin for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:110–117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spankuch B, Kurunci-Csacsko E, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Rational combinations of siRNAs targeting PLK1 with breast cancer drugs. Oncogene. 2007;26:5793–5807. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur S, Pagliarini R, Bunz F, Rago C, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N. A panel of isogenic human cancer cells suggests a therapeutic approach for cancers with inactivated p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3964–3969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813333106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spankuch B, Heim S, Kurunci-Csacsko E, Lindenau C, Yuan J, Kaufmann M, Strebhardt K. Down-regulation of Polo-like kinase 1 elevates drug sensitivity of breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5836–5846. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spankuch B, Steinhauser I, Wartlick H, Kurunci-Csacsko E, Strebhardt KI, Langer K. Downregulation of PLK1 expression by receptor-mediated uptake of antisense oligonucleotide-loaded nanoparticles. Neoplasia. 2008;10:223–234. doi: 10.1593/neo.07916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodel F, Hoffmann J, Distel L, Herrmann M, Noisternig T, Papadopoulos T, Sauer R, Rodel C. Survivin as a radioresistance factor, and prognostic and therapeutic target for radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4881–4887. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlingemann J, Habtemichael N, Ittrich C, Toedt G, Kramer H, Hambek M, Knecht R, Lichter P, Stauber R, Hahn M. Patient-based cross-platform comparison of oligonucleotide microarray expression profiles. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1024–1039. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht R, Oberhauser C, Strebhardt K. PLK (Polo-like kinase), a new prognostic marker for oropharyngeal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2000;89:535–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak O, Keilholz L, Hoffmann A. Pathological features of rectal cancer after preoperative radiochemotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:19–23. doi: 10.1007/s003840050072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama M, Zachariae W, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K. The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1998;17:1336–1349. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descombes P, Nigg EA. The Polo-like kinase Plx1 is required for M phase exit and destruction of mitotic regulators in Xenopus egg extracts. EMBO J. 1998;17:1328–1335. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA. Polo-like kinases: positive regulators of cell division from start to finish. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:776–783. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ree AH, Bratland A, Nome RV, Stokke T, Fodstad O. Repression of mRNA for the PLK cell cycle gene after DNA damage requires BRCA1. Oncogene. 2003;22:8952–8955. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vugt MA, van de Weerdt BC, Vader G, Janssen H, Calafat J, Klompmaker R, Wolthuis RM, Medema RH. Polo-like kinase-1 is required for bipolar spindle formation but is dispensable for anaphase promoting complex/Cdc20 activation and initiation of cytokinesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36841–36854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syljuasen RG, Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, Fugger K, Lundin C, Johansson F, Helleday T, Sehested M, Lukas J, Bartek J. Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:3553–3562. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3553-3562.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppner S, Proschak E, Kaufmann M, Schneider G, Strebhardt K, Spankuch B. Biological impact of freezing PLK1 in its inactive conformation on cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;9:761–774. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]