Abstract

Liver mass is optimized in relation to body mass. Rat (r) and human (h) hepatocytes were transplanted into liver-injured immunodeficient mice and allowed to proliferate for 3 or 11 weeks, respectively, when the transplants stopped proliferating. Liver/body weight ratio was normal throughout in r-hepatocyte-bearing mice (r-hep-mice), but increased continuously in h-hepatocyte-bearing mice (h-hep-mice), until reaching approximately three times the normal m-liver size, which was considered to be hyperplasia of h-hepatocytes because there were no significant differences in cell size among host (mouse [m-]) and donor (r- and h-) hepatocytes. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) type I receptor, TGF-β type II receptor, and activin A type IIA receptor mRNAs in proliferating r-hepatocytes of r-hep-mice were lower than in resting r-hepatocytes (normal levels) and increased to normal levels during the termination phase. Concomitantly, m-hepatic stellate cells began to express TGF-β proteins. In stark contrast, TGF-β type II receptor and activin A type IIA receptor mRNAs in h-hepatocytes remained low throughout and m-hepatic stellate cells did not express TGF-β in h-hep-mice. As expected, Smad2 and 3 translocated into nuclei in r-hep-mice but not in h-hep-mice. Histological analysis showed a paucity of m-stellate cells in h-hepatocyte colonies of h-hep-mouse liver. We conclude that m-stellate cells are able to normally interact with concordant r-hepatocytes but not with discordant h-hepatocytes, which seems to be at least partly responsible for the failure of the liver size optimization in h-hep-mice.

Experiments using animal models with damaged livers have demonstrated the high replicative potential of hepatocytes. A transgenic (Tg) mouse carrying an albumin (Alb) enhancer/promoter-driven murine urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) gene was created1; the liver of this mouse degenerates and increases hepatocyte growth factor production and induces the proliferation of normal hepatocytes.2 When transplanted into the uPA-Tg mice, mouse (m) hepatocytes engrafted into the host liver and proliferated, eventually replacing the host hepatocytes with a replacement index (RI) of 80%,3 where RI represents the ratio of the regions occupied by transplanted hepatocytes in the host liver). The offspring generated by crossing uPA-Tg mice with immunodeficient mice were used as hosts for the xenotransplantation of rat (r),4 woodchuck,5 and human (h) hepatocytes.6,7,8

We showed that the repopulation kinetics of r-hepatocytes in uPA/severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice were different from those of h-hepatocytes.9 Rat hepatocytes rapidly proliferated and completely repopulated the mouse liver, whereas h-hepatocytes proliferated slowly over a longer period, with RI = ∼90%. However, the livers of mice bearing h-hepatocytes (h-hep-mice) became much larger than the normal mass of the host mouse liver as the RI increased, whereas their counterparts with r-hepatocytes (r-hep-mice) did not (unpublished data). The above result with h-hep-mice does not meet the empirical rule (liver size optimization rule) that liver size is determined by the size of an animal’s body.10 This rule says that livers from smaller animals transplanted to larger animals must increase in size, which has been demonstrated in dogs,10 humans,11 and rats.12

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β13,14 and activin15 are potent inhibitors of hepatocyte proliferation. The initiation of TGF-β signaling requires binding to the TGF-β type II receptor (TGFBR2), a constitutively active serine-threonine kinase, which subsequently trans-phosphorylates TGF-β type I receptor (TGFBR1). Activated TGFBR1 phosphorylates the Smad family proteins, Smad2 and 3 (Smad2/3), which then complex with Smad4 and translocate into the nucleus.16 Smad2/3 are also activated by activin and nodal receptors, members of the TGF-β superfamily.17 After partial hepatectomy, TGF-β mRNA expression increased in nonparenchymal cells, and TGF-β seemed to function as an inhibitory paracrine factor to prevent uncontrolled hepatocyte growth.18

When hepatocyte-targeted TGFBR2-knockout (KO) mice were subjected to 70% partial hepatectomy, hepatocytes grew beyond the limit of the known liver/body weight ratio (RL/B),19 supporting the antiproliferative role of TGF-β signaling. However, a similar study with hepatocyte-targeted TGFBR2-KO mice showed no significant differences in RL/B between control and KO mice because of an alternative increase in signaling via activin A/activin A type IIA receptor (ACVR2A) and persistent Smad pathway activity.20 Thus, the roles of TGF-β, activin, and their receptors in the regulation of liver mass remain to be further studied.

In the present study, we compared the repopulation processes of concordant (rat) and discordant (human) xenogeneic hepatocytes in the uPA/SCID mouse liver. Our results showed that r-hep-mice had normal mouse regulation of RL/B, whereas h-hep-mice underwent liver hyperplasia, resulting in the increase in RL/B. The present study strongly suggests that discordant h-hepatocytes fail in exchanging molecular signals including TGF-β/activin with m-hepatic stellate cell (HSCs) and proliferate over the liver size optimization rule for mouse.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Liver Tissues and Hepatocytes

The Hiroshima Prefectural Institute of Industrial Science and Technology Ethics Board approved this study. Liver tissues were obtained from seven donors in hospitals, with informed consent before the operations in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki: four males, a 12-year-old male (12YM), a 28-year-old male (28YM), a 49-year-old male (49YM), and a 50-year-old male (50YM), and three females, a 25-year-old female (25YF), a 61-year-old female (61YF), and a 65-year-old female (65YF). The livers from the 25YF, 28YM, and 61YF were used for real-time RT-PCR to determine the expression levels of cell cycle-related genes and TGFBR/ACVR genes, and those from the 49YM, 50YM, and 65YF were used for immunostaining of proteins. Liver tissues were resected from 13-week-old male Fischer 344 rats (Charles River, Yokohama, Japan) and were used for real-time RT-PCR to determine the expression levels and immunohistochemistry.

h-Hepatocytes were isolated from the 12YM as reported previously.7,21 Cryopreserved h-hepatocytes from two males, a 9-month-old male (9MM) and a 13-year-old male (13YM), were obtained from In Vitro Technologies (Baltimore, MD); h-hepatocytes from a 10-year-old female (10YF) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). The hepatocytes from these four donors were used for transplantation experiments into uPA/SCID mice. r-Hepatocytes were isolated from the livers of Fischer 344 rats by collagenase perfusion,22 centrifuged through 45% Percoll at 50 × g for 24 minutes and used for transplantation experiments. These hepatocyte preparations all showed >80% of viability, which was determined by the dye extrusion test, and >99% of purity, which was determined by microscopic observation.

Transplantation of Hepatocytes

h- and r-Hepatocytes, 7.5 × 105 and 5 × 105 cells, respectively, were transplanted into the liver of homozygous uPA/SCID mice, which had been generated by crossing uPA-Tg mice with SCID mice.7 Donor h-hepatocytes showed reproducibly high engraftment efficiency similar to fresh r-hepatocytes and RI >80% under the optimized conditions. The labeling index (LI) of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) of the transplanted hepatocytes was determined as a measure of DNA synthesis by exposing the host animals to BrdU for 1 hour before sacrifice.23

Histochemistry

Paraffin and frozen sections of 5-μm thickness were prepared from liver tissues as detailed previously.7,23 The sections were stained with H&E or subjected to immunohistochemical analysis using the primary antibodies listed in Table 1 together with necessary information. For bright-field immunohistochemistry, the antibodies were visualized with the VECTASTAIN ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the substrate. The sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Fluorescent immunohistochemistry was performed using Alexa 488- or 594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG or donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) as secondary antibodies and then with Hoechst 33258 for nuclear staining. Human cytokeratin 8/18 (hCK8/18) antibodies reacted with h-hepatocytes but not with m-hepatocytes. Rat major histocompatability complex class I RT1A (rRT1A) antibodies reacted with r-hepatocytes but not with m-hepatocytes. The RIs of h- and r-hepatocytes (RIh-hep and RIr-hep, respectively) were calculated as the ratios of the area occupied by hCK8/18+ h-hepatocytes and the area occupied by rRT1A+ r-hepatocytes to the entire area examined on immunohistochemical sections from six lobes, respectively, as described previously.7 BrdU LIs of h- and r-hepatocytes (LIh-hep and LIr-hep, respectively) were calculated as the ratios of BrdU+ nuclei to hAlb+ h-hepatocytes and rRT1A+ r-hepatocytes, respectively, in 10 randomly selected fields from three different lobes.

Table 1.

Antibodies for Immunohistochemical Analysis

| Antibodies | Clone (clone name) | Host | Dilution | Fixation | Sections | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human CK8/18* | Monoclonal (NCL 5D3) | Mouse | 50 | Aceton | Frozen | MP Biomedicals (Aurora, OH) |

| Human albumin* (cross-adsorbed) | Polyclonal | Goat | 200 | Formalin | Paraffin | Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX) |

| BrdU | Monoclonal (Bu20a) | Mouse | 50 | Formalin | Paraffin | DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark) |

| Rat RT1A† | Monoclonal (OX-18) | Mouse | 100 | Aceton | Frozen | Chemicon International (Temecula, CA) |

| Mouse type IV collagen | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 500 | Aceton | Frozen | LSL (Tokyo, Japan) |

| Human MRP2‡ | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 200 | Aceton | Frozen | Sigma (St. Louis, MO) |

| Human TGFBR2§ | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 500 | Aceton | Frozen | Upstate (Billerica, MA) |

| TGF-β1¶ | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 10 | Formalin | Frozen | BioVision (Mountain View, CA) |

| Human desmin§ | Monoclonal | Mouse | 50 | Formalin | Frozen | DAKO |

| Human Smad2§ | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 50 | Non-fixed | Frozen | Zymed Laboratories (South San Francisco, CA) |

| Human Smad3§ | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 200 | Formalin | Paraffin | Zymed Laboratories |

| Human E-cadherin§ | Polyclonal | Rabbit | 200 | Formalin | Frozen | Abcam (Cambridge, MA) |

Human-specific antibody.

Rat-specific antibody.

Cross-reactive with rat antigen.

Cross-reactive with rat and mouse antigens.

Cross-reactive with TGF-β1-3.

A transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed as follows. Paraffin-embedded liver tissues were sectioned, deparaffinized, and subjected to TUNEL analysis using an ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-Time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from normal and chimeric liver tissues using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) and aliquots, 1 μg each, were reverse-transcribed with random hexamers using PowerScript Reverse Transcriptase (Clontech, Kyoto, Japan). The expressions of the following genes were measured by real-time RT-PCR using an SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems): h-forkhead box M1 (hFoxM1), h-cyclin dependent kinases (hCdk) 1, hCyclin B1, hCyclin D1, h-cell division cycle 25A (hCdc25A), hTGFBR1, hTGFBR2, hACVR2A, h-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (hGAPDH), rat TGFBR1 (rTGFBR1), rTGFBR2, rACVR2A, and rGAPDH. The gene-specific primers we used are shown in Table 2. These primers correctly amplified the corresponding human/rat genes but not the mouse genes. The relative mRNA expressions of transplanted h- and r-hepatocytes were quantified using the comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method24 according to the manual provided by Applied Biosystems. hGAPDH and rGAPDH, respectively, were used as the internal reference genes to normalize the expression of human/rat target genes; h/r-specific primers were used because there is a difference in the amounts of h/r-cDNAs in the mixed baths from the h- or r-hep-mouse liver. Before performing quantification with the ΔΔCT method, we confirmed that the amplification efficiencies of target and reference primers were approximately equal. The expression levels of the target genes show the relative differences from the normal h/r-liver controls. For all data, the h/r target CT value was normalized using the formula: ΔCT = CT h/r target − CT h/rGAPDH. To determine the relative expression levels, the formula, ΔΔCT = ΔCT sample (chimeric livers) − ΔCT calibrator (h/r-livers), was used and 2−ΔΔCT was plotted.

Table 2.

Primer Sets for Real-Time RT-PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| hFoxM1 | 5′-GCATCTACTGCCTCCCTGTG-3′ | 5′-GAGGAGTCTGCTGGGAACG-3′ |

| hCdk1 | 5′-AAACTACAGGTCAAGTGG-3′ | 5′-GGGATAGAATCCAAGTATTTCTTCAG-3′ |

| hCyclin B1 | 5′-CCTGATGGAACTAACTATGTTG-3′ | 5′-CATGTGCTTTGTAAGTCCTTGA-3′ |

| hCyclin D1 | 5′-TGTGAAGTTCATTTCCAATCCG-3′ | 5′-CTGGAGAGGAAGCGTGTGAG-3′ |

| hCdc25A | 5′-CAAAGAGGAGGAAGAGCATGTC-3′ | 5′-CCAGGGATAAAGACTGATGAAGAG-3′ |

| hTGFBR1 | 5′-GGAATTCATGAAGATTACCAAC-3′ | 5′-AGAGTTCAGGCAAAGCTGTAGA-3′ |

| hTGFBR2 | 5′-CATGTGTTCCTGTAGCTCTGAT-3′ | 5′-TGCCGGTTTCCCAGGTTGA-3′ |

| hACVR2A | 5′-AAGAAGACCCTTTGTTGAAAAATG-3′ | 5′-GCAAGGTTTCTCTTAGTCTCATGTC-3′ |

| hSmad2 | 5′-AAAGCTTCACCAATCAAGTCC-3′ | 5′-CTTCTCTTCCTCTTTAATGGG-3′ |

| hSmad3 | 5′-TGGAACTCTACTCAACCCAT-3′ | 5′-GGTAAATGTGTTTGGCAGAC-3′ |

| hGAPDH | 5′-ACCAGGGCTGCTTTTAACTC-3′ | 5′-ATTGATGACAAGCTTCCCG-3′ |

| rTGFBR1 | 5′-CACTTCTGATTCCCACTCTTG-3′ | 5′-ATGAAGGAGCAGGAGCTGTA-3′ |

| rTGFBR2 | 5′-CAAGTCGGTTAACAGCGAT-3′ | 5′-GGCTTCTCACAGATGGAGG-3′ |

| rACVR2A | 5′-AGCATGGATTGGGAGACTTC-3′ | 5′-GCCACATTCTTCGTGTAAGTT-3′ |

| rGAPDH | 5′-CCAGGGCTGCCTTCTCTTGTGA-3′ | 5′-GCCGTTGAACTTGCCGTGGGTA-3′ |

h, human-specific; r, rat-specific.

Statistics

Results are shown as the mean ± SD. Significant differences between groups were detected with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test or Student’s t-tests using StatView software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Growth Kinetics for r- and h-Hepatocytes in uPA/SCID Mice

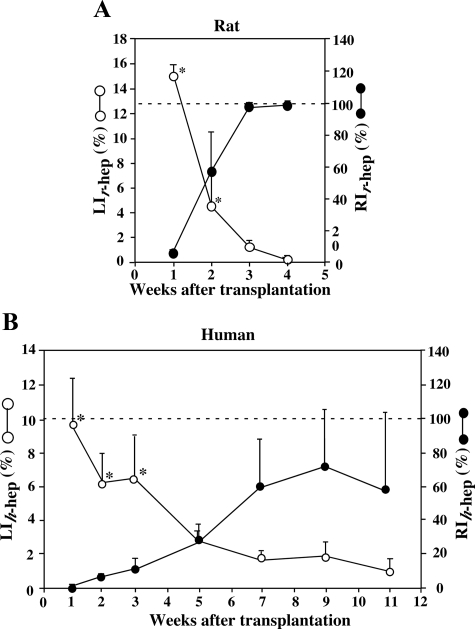

Twelve mice were transplanted with r-hepatocytes and sacrificed at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after transplantation. Liver sections were subjected to double immunostaining for BrdU and rRT1A to determine the LIr-hep and the RIr-hep (Figure 1A), where LIr-hep represents the ratio of the BrdU-positive r-hepatocyte number to the total r-hepatocytes in the r-hepatocyte-repopulated region in the r-hep-mouse liver, and RIr-hep represents the ratio of the repopulated r-hepatocytes to the total r- and m-hepatocytes in the r-hep-mouse liver. LIr-hep was approximately 15% at 1 week, when RIr-hep was approximately 7%. RIr-hep reached almost 100% at 3 weeks when LIr-hep had markedly decreased to 1%. Finally, LIr-hep returned to the control level (0.4%) at 4 weeks, the level of LI of SCID mouse liver. From these results, we concluded that r-hepatocytes terminated proliferation at approximately 3 weeks.

Figure 1.

Repopulation of r- and h-hepatocytes in mice. uPA/SCID mice were transplanted with r-hepatocytes (A) and h-hepatocytes (B) and sacrificed at the indicated times (weeks) after transplantation. A: r-hep-Mice. Histological sections were prepared from three different lobes and stained for rRT1A and BrdU. rRT1A+ and BrdU+ double-positive hepatocytes and rRT1A+ hepatocytes were counted to determine LIr-hep (open circle) and RIr-hep (closed circle), respectively. B: h-hep9MM-Mice. LIh-hep (open circle) and RIh-hep (closed circle) were similarly determined, except that h-hepatocytes were identified using hAlb antibodies. The LI of livers taken from control animals (8- to 15-week-old SCID mice) was 0.4 ± 0.2% (n = 3). Significant differences compared with normal livers (*P < 0.05). The dotted horizontal line indicates RI = 100%.

Mice were transplanted with h-hepatocytes isolated from the 9MM (h-hep9MM) and were sacrificed at 1 to 11 weeks after transplantation (Figure 1B). LIh-hep and RIh-hep, the corresponding ratios for h-hep-mouse liver, were approximately 10% and <1% at 1 week, respectively. The LIh-hep at this time period was 64% of the LIr-hep. The rise of RIh-hep and the decrease of LIh-hep thereafter were both greatly slow compared with those of the r-hep-mice. LIh-hep returned to the control level at 11 weeks when RIh-hep was still as low as 58 ± 46%. Thus, it was concluded that h-hepatocytes repopulate the m-liver quite slowly. We believe that this difference in donor proliferative and repopulating activities is due to species-related differences but not experimental variables that might influence transplantation outcomes, because, first, the engraftment efficiencies were similar between the h- and the r-hepatocytes, second, the viability (>80%) and the purity (>99%) of the hepatocyte preparations were comparable between the two types of hepatocytes, and, third, the similar difference was observed in the previous report in which h-hepatocytes were also used as donor hepatocytes.9

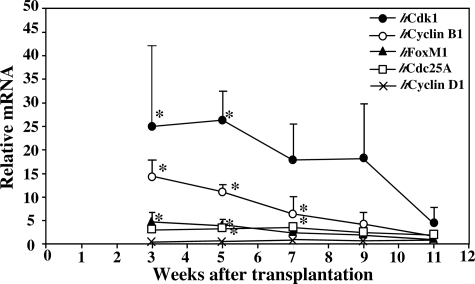

Information regarding proliferative activity of h-hepatocytes was obtained by determining the gene expression levels of five cell cycle promotion genes (hCdk1, hCyclin B, hFoxM1, hCdc25A, and hCyclin D) in the h-hep-mouse livers during repopulation, together with those in normal h-livers from three donors. The results are shown as the relative mRNA expression levels against those in the normal h-livers (Figure 2). h-hep-Mouse livers expressed hCdk1 and hCyclin B1 at much and moderately higher levels at 3 to 9 weeks, respectively. The expressions of hFoxM1 and hCdc25A were significantly higher in h-hep-mouse livers up to 7 weeks. These genes all reduced the expression to levels comparative to normal h-liver levels at 11 weeks. These results indicate that h-hepatocytes in h-hep-mice terminated growth at 11 weeks after transplantation.

Figure 2.

Expressions of cell cycle-related genes during h-hepatocyte repopulation in h-hep-mice. h-hep-Mouse livers were removed at 3 to 11 weeks after transplantation from h-hep-mice shown in Figure 1B and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for hCdk1 (closed circle), hCyclin B1 (open circle), hFoxM1 (closed triangle), hCdc25A (open square), and hCyclin D1 (×). Gene expressions were also determined for normal human livers from the 25YF, 28YM, and 61YF donors. Gene expressions were all normalized to hGAPDH expression. The ratio of mRNA expression for each gene in h-hep-mouse livers was calculated by dividing the normalized value of each gene of h-hep-mouse livers by the normalized value of corresponding gene of the normal h-livers. The ratios are plotted against weeks after transplantation. The variation of each gene of the normal livers was 1.0 ± 0.3, 1.0 ± 0.6, 1.0 ± 0.4, 1.0 ± 0.5, and 1.0 ± 0.3 for hFoxM1, hCdk1, hCyclin B1, hCyclin D1, and hCdc25A, respectively. Significant differences against normal h-livers (*P < 0.05).

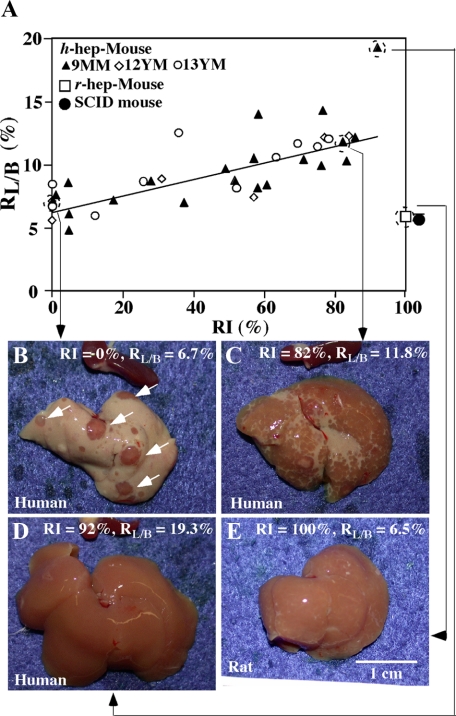

Correlation of RL/B with RI in h-Chimeric Mice

In the experiments shown in Figure 1, we noticed that the h-hep-mouse liver enlarged beyond the normal volume of the host liver as RIh-hep increased. We assessed a correlation between RIh-hep and liver mass during h-hepatocyte repopulation. A total of 38 h-hep-mice were generated using h-hepatocytes from three donors (9MM, 12YM, and 13YM) and were sacrificed at 11 to 14 weeks after transplantation. No significant increase in blood hAlb levels was observed at 9 to 10 weeks, indicating that the livers then had entered the termination phase of growth, which is consistent with the results shown in Figure 2. Host liver and body weights were measured at sacrifice to calculate RL/B. Liver sections were prepared from each mouse and stained for hCK8/18 to determine RI. RL/B was then plotted against RI (Figure 3A). RL/B increased as RI increased, with a correlation coefficient (r2) of 0.59. The gross appearances of the selected h-hep-mouse livers are shown in Figure 3, B–D. Livers of an h-hep-mouse with RI = 0% showed RL/B = 6.9 ± 1.0% (Figure 3, A and B). Twenty of the 38 h-hep-mice showed RI >50%. Five h-hep-mice showed RIs >80%, one of which had RL/B = 11.8% and is shown in Figure 3C. The highest RI was 92.1%, which was obtained in a chimeric h-hep9MM mouse with RL/B = 19.3% (Figure 3D). The RL/B for the five mice with RIs >80% was 13.2 ± 3.5%, which was >2-fold of the value at the time of transplantation (6.0 ± 1.1%, n = 4) or that (5.4 ± 0.5%, n = 3) observed in SCID mice (Figure 3A). Importantly, the RL/B of r-hep-mice did not change during repopulation (Figure 3E, 5 weeks) and was similar to that of SCID mice (5.4 ± 0.5%, n = 3): RL/B = 6.5 ± 1.1, 6.3 ± 0.2, 6.4 ± 0.2, and 5.8 ± 0.2% (each n = 3), at 2, 3, 4, and 5 weeks after transplantation, when RIs were 57.1 ± 24.7, 97.1 ± 3.0, 98.6 ± 2.4, and 100 ± 0.0%, respectively. This fact suggests that the increase in r-hepatocyte number and the death of injured m-hepatocytes are normally balanced in the r-hep-mouse liver. However, RL/B of h-hep-mice increased as the RI increased as above, suggesting a possible imbalance between h-hepatocyte proliferation and m-hepatocyte death.

Figure 3.

Correlation of RL/B with RI in h-hep-mice. A: Twenty-one, 6, and 11 h-hep-mice were produced by transplanting hepatocytes from the 9MM, 12YM, and 13YM donors, respectively, and then sacrificed at 11 to 14 weeks after transplantation. RL/B and RI were determined at sacrifice and plotted together. Closed triangle, 9MM hepatocytes; open diamond, 12YM hepatocytes; open circle, 13YM hepatocytes. Four r-hep-mice were produced and sacrificed at five weeks after transplantation when the repopulation had completed, and RL/B and RI were determined (open square). RL/B was also determined for three 8- to 15-week-old SCID mice (closed circle). B–D: Gross appearances of h-hep-mouse livers at 11 weeks. The four long arrows in the figure starting from each of mouse symbols in A point to the photos of the corresponding mouse livers shown in B, C, D, and E, respectively. B: The liver of an h-hep9MM mouse with RI = 0% and RL/B = 6.7%. Arrows indicate reddish colonies of m-hepatocytes that deleted the transgene. Whitish regions are occupied by Tg host hepatocytes. The dark red-colored organ placed above the liver is spleen removed from the same recipient. C: The liver of an h-hep9MM mouse with RI = 82% and RL/B = 11.8%. D: The liver of an h-hep9MM mouse with RI = 92% and RL/B = 19.3%. E: The liver of an r-hep-mouse with RI = 100% and RL/B = 6.5%. Scale bar = 1 cm.

To test this possibility we performed the TUNEL analysis and determined the ratios (%) of the TUNEL+ (dead) m-hepatocytes during the repopulation of h-hepatocytes as follows: 0.5 ± 0.1, 0.6 ± 0.2, 1.2 ± 0.1, 0.6 ± 0.3, 0.2 ± 0.1, 3.9 ± 4.7, and 8.5 ± 6.8 at 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 weeks (each n = 3), respectively. The ratios were quite low until 7 weeks after transplantation and were much lower than those of the BrdU+ h-hepatocytes shown in Figure 1B (∼10% at 1 week and ∼2% at 7 weeks). Similar TUNEL analysis showed a TUNEL+ ratio of 18.8 ± 6.1% (n = 3) for r-hep-mice at 3 weeks after transplantation, which is considerably higher than that of h-hep-mice at 3 weeks (1.2 ± 0.1%). Based on these analyses, we concluded that the proliferation rate of h-hepatocytes is higher than the death rate of m-hepatocytes, which resulted in the enlargement of liver in h-hep-mice.

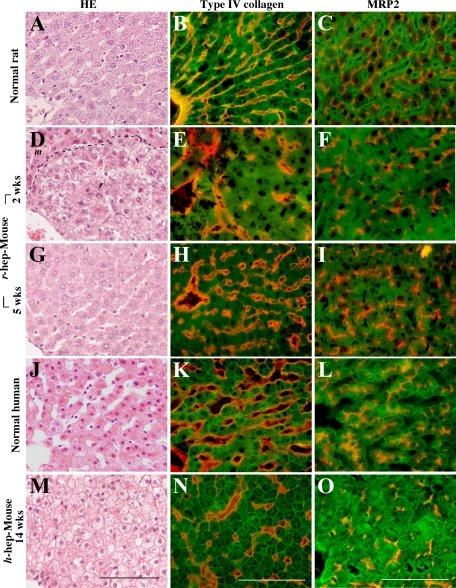

Histological Architecture of Sinusoids and Bile Canaliculi in Chimeric Mouse

Liver sinusoids were histologically examined, because their structures reflect the proliferation status of hepatocytes: their structures are compressed25 and become vague26 during vigorous hepatocyte proliferation. r-hep- and h-hep9MM Mice were generated and sacrificed in the proliferation (at 2 and 5 weeks after transplantation for r-hep- and h-hep9MM mice, respectively) and proliferation termination phases (at 5 and 14 weeks for r-hep- and h-hep9MM mice, respectively) for histological analysis (Figure 4). Normal livers from Fischer 344 rats and the 65YF donor were used as normal r- and h-liver controls, respectively. H&E sections clearly showed the single-cell structures of hepatic plates in normal r-livers (Figure 4A) and h-livers (Figure 4J). Sections were stained for type IV collagen, an indicator of the subsinusoidal space,26 and multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2), a maker of the canalicular organic anion transporters.27 These proteins were localized as expected in normal r-livers (Figure 4, B and C) and h-livers (Figure 4, K and L).

Figure 4.

Histological characteristics of r-hep- and h-hep-mouse livers. Normal r- and h-livers were obtained from 13-week-old male Fischer 344 rats (A–C) and from a 65YF donor (J–L), respectively. r-hep-Mice and h-hep-mice were produced as shown in Figure 1. The former were sacrificed at two (proliferation phase, D–F) and five weeks (wks) after transplantation (termination phase, G–I) and the latter at 14 weeks (termination phase, M–O). Liver sections were stained with H&E (A, D, G, J, and M) and for type IV collagen (red, B, E, H, K, and N) and MRP2 (red, C, F, I, L, and O). The sections from rats and r-hep-mice were additionally stained for rRT1A (green, B, C, E, F, H, and I) and those from the human and h-hep-mice for hCK8/18 (green, K, L, N, and O) to identify transplanted r- and h-hepatocytes, respectively. The dashed line in D shows the boundary between r-hepatocyte (r) and m-hepatocyte regions (m). Scale bar = 100 μm.

H&E-stained sections from r-hep- and h-hep-mouse livers at 5 and 14 weeks, respectively, showed complete repopulation (Figure 4, G and M, respectively), but their histological features were quite different. h-Hepatocytes were less eosinophilic than r-hepatocytes, as reported previously,7 and swollen and contained less cytoplasm, with wisps of accumulated glycogen, as described previously.8 Single-cell plates were rarely observable in the h-hepatocyte-regions in h-hep-mice at 14 weeks (Figure 4M), and sinusoids were obscure. Type IV collagen immunostains demonstrated multicell-layer-thick hepatic plates (Figure 4N). The MRP2 protein was randomly distributed in the intercellular space (Figure 4O). Similar histological structures were observed in the h-hepatocyte regions at 5 weeks (data not shown). Likewise sinusoidal structures were not distributed in an orderly fashion in the r-hepatocyte regions of r-hep-mice at 2 weeks when r-hepatocytes were in the proliferation phase (Figure 4, D–F), losing vessel continuity along the portal-central axis. However, r-hep-mice at 5 weeks after transplantation regained the normal arrangement of hepatic plates and sinusoids (Figure 4G), which was consistent with the distributions of type IV collagen and MRP2 (Figure 4, H and I). These proteins were located as in normal r-liver, indicating the reconstruction of the resting liver structure with single hepatic plates along the portal-central axis. These results demonstrate that the h-hepatocytes were incapable of reconstructing the resting liver structure even at 14 weeks after transplantation.

The length of the long axis of hepatocytes was determined on H&E-stained sections from r- and h-hep-mice shown in Figure 4 as a measure of size, which showed no significant differences among m (host)-, r-, and h-hepatocytes in chimeric livers: uPA-expressing m-hepatocytes in h-hep9MM mice at 11 weeks after transplantation, 19.5 ± 4.5 μm (n = 3); uPA-expressing m-hepatocytes in r-hep-mice at 2 weeks, 19.7 ± 4.3 μm (n = 3); r-hepatocytes in r-mice at 5 weeks, 22.7 ± 2.9 μm (n = 3); and h-hepatocytes in h-hep-mice at 11 to 14 weeks, 22.5 ± 1.8 μm (n = 6). This result clearly indicated that the observed enlargement of the h-hep-mouse liver was caused by hyperplasia but not hypertrophy of h-hepatocytes.

TGF-β Signaling in r-hep- and h-hep-Mouse Livers

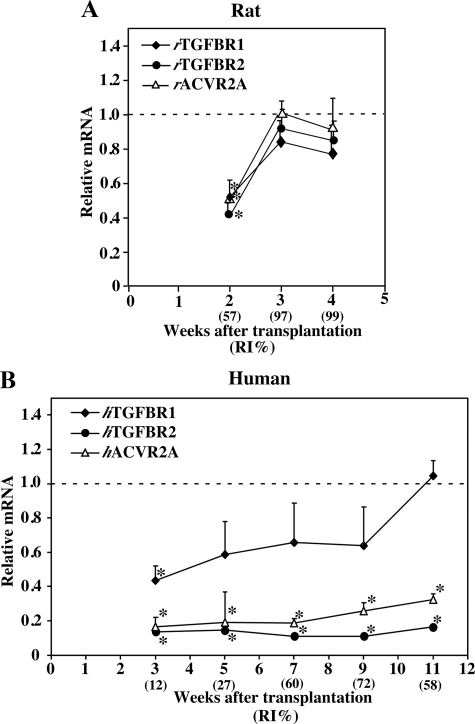

TGF-β and activin play active roles in the termination of liver regeneration.14,15,18,19,20,28 The mRNA expressions of TGFBR1, TGFBR2, and ACVR2A were determined in r-hep-mouse livers at 2, 3, and 4 weeks after transplantation and in h-hep9MM mouse livers at 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 weeks and compared with those of normal r- and h-liver controls, respectively. In r-hep-mice at 2 weeks (proliferation phase, RIr-hep = 57%), rTGFBR1, rTGFBR2, and rACVR2A expressions were suppressed to half those of normal r-livers and gradually returned to normal levels at 3 and 4 weeks (termination phase, RIr-hep = 97 and 99%, respectively) (Figure 5A) as reported in the regeneration of partial hepatectomized r-liver.29 In contrast, their expression profiles in h-hep-mouse livers were quite different (Figure 5B). At 3 weeks (proliferation phase, RIh-hep = 12%), hTGFBR2 and hACVR2A were expressed at levels less than one-third of normal levels; expression remained low throughout the 11-week-long observation period. The suppression of the expression of these genes was reproducible, because similar results were obtained from h-hep-mice generated with another donor (10YF): the ratios of expression levels of hTGFBR2 and hACVR2A in the h-hep-mice at 9 to 11 weeks after transplantation to those in the normal human livers were 0.19 ± 0.05 (n = 3) and 0.19 ± 0.02 (n = 3), respectively. The expression of hTGFBR1 mRNA was high compared with that of these two mRNAs at 3 weeks and gradually increased until reaching the normal levels at 11 weeks.

Figure 5.

Gene expressions of TGFBR1, TGFBR2, and ACVR2A in r-hep- and h-hep-mouse livers. Real-time RT-PCR was performed by using total mRNA isolated from the livers of r-hep- and h-hep9MM mice shown in Figure 1 as templates, and each result was normalized to that of rGAPDH and hGAPDH. Likewise real-time RT-PCR was performed for liver tissues from 13-week-old male rats and those from the 25YF, 28YM, and 61YF human donors as the normal rat and human controls, respectively. mRNA abundance in r- and h-chimeric mice was divided by that of the normal r- and h-livers, respectively, and is shown as relative mRNA abundance (ordinary axis) in A for r-hep-mice and in B for h-hep-mice. Normal livers in A were obtained from three 13-week-old male rats and those in B from three donors, 25YF, 28YM, and 61YF. The dotted horizontal lines show the average expression level in normal livers (1.0). The variations of the normalized rTGFBR1, rTGFBR2, rACVR2, hTGFBR1, hTGFBR2, and hACVR2 were 1.0 ± 0.2, 1.0 ± 0.2, 1.0 ± 0.2, 1.0 ± 0.2, 1.0 ± 0.4, and 1.0 ± 0.2, respectively. Values represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). Significant differences compared with normal livers (*P < 0.05). “RI%” shows the average RI calculated from three mice. Closed diamond, TGFBR1; closed circle, TGFBR2; and open triangle, ACVR2A.

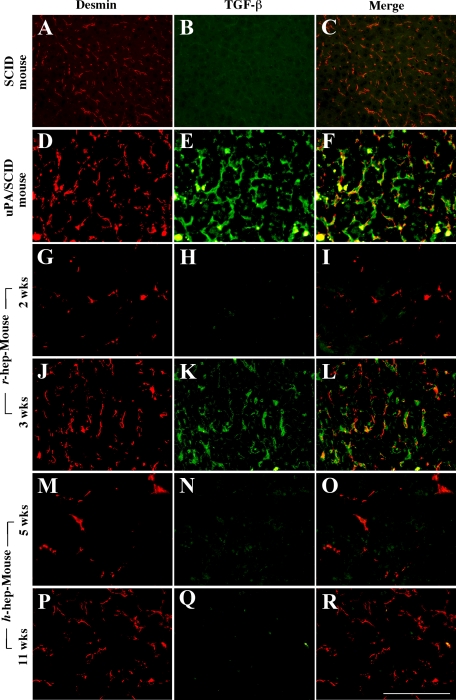

The expression of TGF-β receptor, TGFBR2, was immunohistochemically examined in r- and h-hep9MM mouse livers at 3 and 11 weeks when the mice showed RI = 97 ± 3% (n = 3) and 58 ± 46% (n = 3), respectively, together with staining for rRT1A and hCK8/18 to identify r- and h-hepatocytes, respectively (Figure 6). As with normal r-hepatocytes (Figure 6, A–C), the rRT1A+ r-hepatocytes in r-hep-mice were stained heavily for TGFBR2 (Figure 6, D–F). Likewise normal h-hepatocytes abundantly expressed TGFBR2 (Figure 6, G–I). In contrast, TGFBR2 was hardly detectable in hCK8/18+ h-hepatocytes in h-hep-mice (Figure 6, J–L). The anti-TGFBR2 antibody used was cross-reactive with r- and m-TGFBR2. The TGFBR2+ cells in the m-hepatocyte region seen in Figure 6K were largely m-hepatocytes according to their morphology. Moderately TGFBR2+ cells in the h-hepatocyte region shown in Figure 6K were mostly m-nonparenchymal cells and few h-hepatocytes (Figure 6, K and L). These results indicated that h-hepatocytes in h-hep-mice maintain low sensitivity to TGF-β, although the expression of TGFBR1 was up-regulated at 11 weeks after transplantation. It is known that TGF-β initially binds to TGFBR2, and TGF-β signals are transferred through the heterodimers of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2.16 TGF-β-expressing cells were identified in liver sections from r- and h-hep-mice during the proliferation and termination phases by double-immunostaining for desmin and TGF-β (Figure 7). Compared with the control (Figure 7, A–C; normal liver from wild-type SCID mice), tissues collected from the injured livers of uPA/SCID mice contained abundant desmin+ HSCs that were all heavily expressing TGF-β (Figure 7, D–F) as reported previously.2 Very few desmin+ cells were observed in r-hep-mice at 2 weeks (Figure 7, G–I) or in h-hep-mice at 5 weeks (Figure 7, M–O), suggesting that very few m-HSCs invaded the xenogeneic hepatocyte colonies during the proliferation phase. These cells were all TGF-β−. m-HSCs increased in number in xenogeneic hepatocyte colonies from both r- and h-hep-mice, particularly in the former, at 3 and 11 weeks (termination phase), respectively (Figure 7, J and P). During the termination phase, m-HSCs in r-hepatocyte colonies from r-hep-mice were TGF-β+ (Figure 7, J–L). However, importantly, m-HSCs in h-hepatocyte colonies of h-hep-mice were TGF-β− (Figure 7, P–R). HSCs that express TGF-β should be all m-HSCs in the chimeric mice, because the purity of the transplanted r- or h-hepatocytes was >99%. In r- and h-normal livers, TGF-β+-HSCs were rarely observed (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Identification and distribution of TGFBR2 in normal and chimeric livers. uPA/SCID mice were transplanted with r- and h-hepatocytes9MM and sacrificed at 3 and 11 weeks after transplantation, respectively, when the transplanted hepatocytes had terminated proliferation. Two series of double immunohistochemical examinations were performed on liver tissues, one for rat series (Rat) shown in A–F that contained normal r-liver (Normal rat) shown in A–C and r-hep-mouse liver (D–F) and the other for the human series (Human) shown in G–L that contained 9MM donor liver as control normal h-liver (Normal human, G–I) and h-hep-mouse liver (J–L). Liver sections of rat series were double-stained for rRT1A for identifying r-hepatocytes (green; A and D) and TGFBR2 (red; B and E) and those of human series for hCK8/18 for identifying h-hepatocytes (green; G and J) and TGFBR2 (red; H and K). Images A and B, D and E, G and H, and J and K were merged and are shown in C, F, I, and L, respectively. Similar staining results were obtained from three different mice of each series. The dashed lines in J–L indicate the boundary between h-hepatocyte (h) and m-hepatocyte regions (m). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 7.

Expression and distribution of TGF-β in normal and chimeric mouse livers. Livers were removed, respectively, from 3-month-old wild-type SCID mice (A–C), 1-month-old uPA/SCID mice (D–F, injured region), r-hep-mice at 2 (G–I) and three (J–L) weeks after transplantation, and h-hep-mice at 5 (M–O) and 11 weeks (P–R). These livers were cryosectioned and double-immunostained for desmin (A, D, G, J, M, and P, red) and TGF-β (B, E, H, K, N, and Q, green). The two sets of photographs are merged and shown in the corresponding panels (C, F, I, L, O, and R) in the right column. Serial sections from r- and h-hep-mouse livers were immunostained for rRT1A and hCK8/18 to identify r- and h-hepatocytes, respectively (data not shown). Similar results were obtained from three different mice. Scale bar = 100 μm.

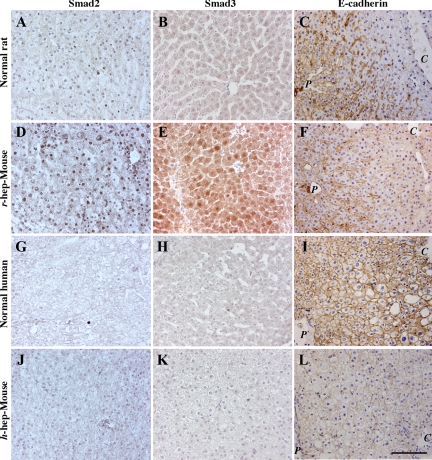

Smad proteins are major intracellular effectors in both TGFBR and ACVR signaling. The distributions of Smad2/3 were examined on liver sections prepared from r- and h-hep-mice at 3 and at 11 weeks (termination phase of r- and h-hep-mice, respectively), respectively, together with liver tissues from Fischer 344 rats and the 49YM donor as normal controls (Figure 8). The nuclei of normal r-livers (Figure 8, A and B) and h-livers (Figure 8, G and H) were both Smad2−/3−. In contrast, the nuclei of r-hepatocytes in r-hep-mouse were strongly Smad2+/3+ (Figure 8, D and E), supporting the evidence that r-hepatocytes are activated by TGF-β from m-HSCs. However, as expected, h-hepatocytes showed little or no Smad2/3 immunoreactivity (Figure 8, J and K), suggesting that TGF-β and activin signaling was lacking in h-hep-mice. In h-hep mice from another donor (10YF, 9 to 11 weeks after transplantation), the immunohistological results for TGF-β, Smad2, and Smad3 showed the same tendencies as the results shown in Figures 7 and 8 (data not shown), suggesting that the deficiency of TGF-β signaling is not attributed to the possible immaturity because of the young age (9MM) of the donor.

Figure 8.

Localization of Smad2/3 and E-cadherin in chimeric mouse liver. Livers were obtained from 13-week-old male Fischer 344 rats (A–C, Normal rat), normal donors (49YM, 50YM, and 65YF) (G–I, Normal human), r-hep-mice at three weeks (D and E) and five weeks (F), and 9MM-h-hep-mice at 11 weeks (J and K) and 14 weeks (L) after transplantation. They were immunostained for Smad2 (A, D, G, and J), Smad3 (B, E, H, and K), and E-cadherin (C, F, I, and L). Positive signals are brown. Histological examinations were individually performed for these livers in each category, and we obtained similar results. Representative photos are shown here. The photos of Normal human were from 49YM liver. In C, F, I, and L, P and C indicate portal and central veins, respectively. Scale bar = 100 μm.

To obtain an additional evidence for the TGF-β signaling deficiency in h-hep-mice, we examined the expression of E-cadherin in the chimeric mouse, which is one of the TGF-β target genes.30 Normal r-livers expressed the E-cadherin protein in the periportal zone restrictedly (Figure 8C), and a similar distribution pattern was observed in the r-hep-mouse livers (Figure 8F). In contrast to normal r-livers, normal h-livers uniformly and evenly expressed E-cadherin (Figure 8I). Its expression was significantly low in the h-hepatocyte region of the h-hep-mouse liver (Figure 8I) compared with that in the normal h-livers.

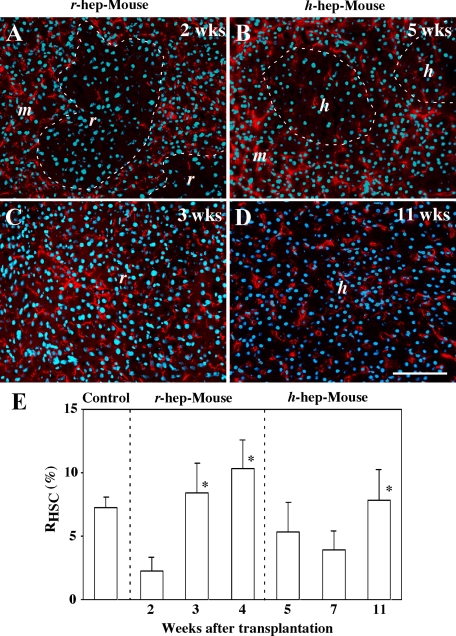

Participation of m-HSCs in the Donor Hepatocyte Colonies

As shown in Figure 7, the xenogeneic hepatocyte regions contained fewer m-HSCs than the injured host regions, especially in the proliferation phase. We further investigated this phenomenon using desmin as a HSC marker. The desmin+ cells were scarce in both r- and h-hepatocyte colonies in r-hep-mice at 2 weeks (Figure 9A) and in h-hep-mice at 5 weeks after transplantation (Figure 9B), respectively, compared with the degenerating m-hepatocyte regions that surrounded the corresponding donor cell regions. These xenogeneic hepatocytes were both in the proliferation phase (Figure 1). This paucity of HSCs seemed to be related to the fact that the sinusoids were still under reconstruction (Figure 4E) in r-hep-mouse liver at 2 weeks and in h-hep-mouse liver at 5 weeks (data not shown). HSCs were abundant in r-hepatocyte colonies in r-hep-mice at 3 weeks (termination phase) (Figure 9C), supporting the result of Figure 7J. The HSCs also increased in density in h-hepatocyte colonies of h-hep-mice at 11 weeks (Figure 9D), also supporting the result of Figure 7P. However, the density was apparently lower than that in r-hepatocyte colonies, most probably reflecting the fact that the sinusoids were less developed than in r-hepatocyte colonies in the termination phase (Figure 4N versus Figure 4H, respectively). These desmin+ HSCs were not derived from h-HSCs, because, first the purity of the transplanted h-hepatocytes was >99% and second h-HSCs do not express desmin.31 The m-HSC-occupied areas (red-colored areas) were measured in the entire normal mouse (wild-type SCID mouse) liver (control) and in the xenogeneic hepatocyte regions of chimeric livers on immunostained sections. The ratios (RHSC) of red-colored areas to either the entire liver of SCID mouse or to the xenogeneic region of chimeric liver were calculated and are shown in Figure 9E. The RHSC in normal mice was 7.3 ± 0.8%. In r-hep-mice, the RHSC was 2.3 ± 1.1% at 2 weeks and increased to 10.3 ± 2.3% at 4 weeks. In h-hep-mice, the RHSC was approximately 5% for up to 7 weeks and significantly increased to 7.8 ± 2.4% (P < 0.01) at 11 weeks. The RHSC of r-hep-mice at 4 weeks was significantly higher than that of h-hep-mice at 11 weeks (P < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Distribution of m-HSCs in r- and h-hep-mice. Liver sections from r-hep-mice at two (proliferation phase, A) and three (termination phase, C) weeks and from 9MM h-hep-mice at five (proliferation phase, B) and 11 (termination phase, D) weeks after transplantation were immunostained for desmin (red). The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33258 (blue). Serial sections from the r-hep- and h-hep-mouse livers were immunostained for rRT1A and hCK8/18 to identify r-and h-hepatocytes, respectively (data not shown), from which the boundary between the host (m) and transplanted (r or h) hepatocyte regions was determined, as indicated by the dashed lines in A and B. Similar results were obtained from three different mice. Scale bar = 100 μm. E: Changes in the ratio of desmin+ cells in xenogeneic hepatocyte regions during liver repopulation. Liver sections from 3-month-old wild-type SCID mice (control), r-, and h-hep-mice at the indicated weeks after transplantation were immunostained for desmin. Serial sections were stained with anti-rRT1A and -hCK8/18 antibodies to identify r- and h-hepatocytes, respectively. The ratio (RHSC) of desmin+ areas over the measured areas was calculated in the xenogeneic hepatocyte region using NIH imaging software and is expressed as a percentage. Data represent the mean ± SD of desmin+ area per section in a total of 15 randomly selected fields (n = 3). Asterisks at three and four weeks in the panel for r-hep-mice indicate significant differences versus the value at two weeks. The asterisk at 11 weeks in the panel of h-hep-mice indicates a significant difference versus the value at five weeks.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the repopulation processes between r- and h-hepatocytes in the livers of uPA/SCID mice and showed several physiologically significant differences. The r-hepatocytes rapidly replaced m-hepatocytes to keep a normal RL/B, suggesting a repopulation in a strictly regulated manner. The r-hepatocytes expressed TGFBR1/2 mRNAs at lower levels in the proliferation phase and then gradually increased expressions in the termination phase when m-HSCs actively expressed TGF-β. Moreover, Smad2/3 were translocated in r-hepatocyte nuclei, suggesting that TGF-β/TGFBR/Smad signaling normally works as in the terminal phase of mouse liver regeneration.

In the chimeric animal h-hepatocytes were quite different from r-hepatocytes. They proliferated much slowly, requiring approximately four times longer to complete proliferation than r-hepatocytes. The resulting liver showed marked overgrowth compared with a normal m-liver. TGFBR2 and ACVR2A, and TGF-β were not up-regulated in h-hepatocytes and m-HSCs of h-hep-mice, respectively, in the termination phase, indicating the absence of physiologically meaningful signaling between h-hepatocytes and m-HSCs. The density of m-HSCs in h-hepatocyte colonies was lower than that in r-hepatocyte colonies even in the termination phase, which probably reflects the poor development of sinusoids in h-hep-mice, because the multiple hepatic plates would result in the lower volume of the space of Disse than in the liver with single hepatic plates. It has been reported that intimate signaling between hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells plays an important role in the termination of liver regeneration.32 Thus, the failure of m-HSCs to express TGF-β could be a cause of liver hyperplasia of h-hep-mice. However, it is appropriate to note here that other factors such as hepatocyte growth factor33 and bile acids34 might be involved in the observed hyperplasia.

In TGFBR2 knockout mice, partial hepatectomy resulted in a 1.2-fold increase beyond the normal liver weight because of a compensatory increase in activin A/ACVR2A signaling and persistent activity in the Smad pathway.20 Unlike in the study cited, the levels of ACVR2A mRNA and Smad proteins remained low through the experimental period in the present study with h-hep-mice. Thus, the lack of both TGF-β and activin signaling may have been partly responsible for the observed overgrowth of hepatocytes. We did not observe any symptoms of carcinogenic transformation in h-hepatocytes (data not shown), although TGFBR235 and ACVR236 are putative tumor suppressors, suggesting a requirement for additional factor(s) for hepatocarcinogenesis.

Even in the absence of TGF-β/TGFBR signaling, the transplanted h-hepatocytes eventually terminated proliferation. The histological features of sinusoids and canaliculi in mouse liver repopulated by xenogeneic hepatocytes demonstrated that h-hepatocytes did not restore the normal arrangement of single hepatic plates in the resting phase of the liver, but they formed multiple hepatic plates seen in the regenerating liver.25,26 Thus, it is most likely that h-hepatocytes eventually terminated the proliferation because of contact inhibition within the multiple hepatocyte layers. r-Hepatocytes also formed multiple hepatic plates in the proliferation phase but restored the normal structures of single cell plates along the portal-central axis in the termination phase. It seems that TGF-β/TGFBR signaling is required for both the formation of single hepatic plates and the normal termination of liver growth. These apparently distinct events (liver growth termination and hepatic plate structuring) should be closely related at the molecular levels, because adhesion molecules such as E-cadherin and β1-integrin are reported as the Smad2/3-mediated TGF-β target genes in liver development.30 Our results demonstrated that E-cadherin uniformly exists on the hepatocyte surfaces in the normal h-liver, but its expression was quite low in substantial portions of the h-hepatocyte region in the h-hep-mouse liver. It is likely that this expression defect in the cell adhesion molecule results in abnormal hepatocyte plate arrangements. Loss of TGF-β signaling in h-hep-mice might be responsible for the maintenance of multicell-thick hepatic plates after the termination of liver repopulation in the h-hep-mouse livers.

There is the possibility that the observed hyperplasia of h-hepatocytes is the result of a signaling failure between m-cytokine ligands and the corresponding h-receptors. Recently, we showed that h-hepatocytes in h-hep-mice are growth hormone-deficient, because mouse growth hormone does not recognize the human growth hormone receptor of h-hepatocytes.37 However, we consider that h-hepatocytes would be able to respond to TGF-β if the host m-HSCs secreted it, because there has been no report of species specificity between h- and m-TGF-β. In the present study we clearly demonstrated the coincidence of lack of TGF-β/TGFBR signaling with the hyperplasia of h-hep-mouse liver. However, the direct causality between such signaling and the liver hyperplasia remains to be examined. It is well known that hepatocytes and stellate cells interact with each other through varieties of signaling molecules and together contribute to physiological and pathological changes of liver. Therefore, we conclude that the lack of or weak interaction between h-hepatocytes and m-HSCs, which we have revealed at the histological and gene/protein expression levels, is responsible for the presently observed hyperplasia of h-hep-mouse liver.

Xenotransplantation, such as from pigs to humans, could potentially compensate for the lack of human organ and tissue donors. Our results indicate that, in addition to potential immunological rejection, the transplanted cells or tissues may fail to interact appropriately with the host environment. We propose that the h-chimeric mouse is a useful model for not only examining the mechanism of liver regeneration but also studying risks of xenotransplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yasumi Yoshizane, Hiromi Kohno, Yoko Matsumoto, and Sanae Nagai for technical assistance and Dr. Masumi Yamada for helpful discussion and comments.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Katsutoshi Yoshizato, Ph.D., PhoenixBio Co., Ltd., 3-4-1 Kagamiyama, Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima 739-0046, Japan. E-mail: katsutoshi.yoshizato@phoenixbio.co.jp.

Supported in part by Cooperative Link of Unique Science and Technology for Economy Revitalization (CLUSTER), Promotion of Science and Technology in Regional Areas, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

None of the authors declare any relevant financial relationships.

References

- Heckel JL, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Neonatal bleeding in transgenic mice expressing urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Cell. 1990;62:447–456. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90010-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locaputo S, Carrick TL, Bezerra JA. Zonal regulation of gene expression during liver regeneration of urokinase transgenic mice. Hepatology. 1999;29:1106–1113. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim JA, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Replacement of diseased mouse liver by hepatic cell transplantation. Science. 1994;263:1149–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.8108734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim JA, Sandgren EP, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Complete reconstitution of mouse liver with xenogeneic hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4942–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandri M, Burda MR, Gocht A, Török E, Pollok JM, Rogler CE, Will H, Petersen J. Woodchuck hepatocytes remain permissive for hepadnavirus infection and mouse liver repopulation after cryopreservation. Hepatology. 2001;34:824–833. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandri M, Burda MR, Török E, Pollok JM, Iwanska A, Sommer G, Rogiers X, Rogler CE, Gupta S, Will H, Greten H, Petersen J. Repopulation of mouse liver with human hepatocytes and in vivo infection with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2001;33:981–988. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateno C, Yoshizane Y, Saito N, Kataoka M, Utoh R, Yamasaki C, Tachibana A, Soeno Y, Asahina K, Hino H, Asahara T, Yokoi T, Furukawa T, Yoshizato K. Near completely humanized liver in mice shows human-type metabolic responses to drugs. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:901–912. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63352-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman P, Libbrecht L, De Vos R, de Hemptinne B, Gevaert K, Vandekerckhove J, Roskams T, Leroux-Roels G. Morphological and biochemical characterization of a human liver in an uPA-SCID mouse chimera. Hepatology. 2005;41:847–856. doi: 10.1002/hep.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto K, Tateno C, Hino H, Amano H, Imaoka Y, Asahina K, Asahara T, Yoshizato K. Efficient in vivo xenogeneic retroviral vector-mediated gene transduction into human hepatocytes. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1168–1674. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam I, Lynch S, Svanas G, Todo S, Polimeno L, Francavilla A, Penkrot RJ, Takaya S, Ericzon BG, Starzl TE, Van Thiel DH. Evidence that host size determines liver size: studies in dogs receiving orthotopic liver transplants. Hepatology. 1987;7:362–366. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Kam I, Francavilla A, Polimeno L, Schade RR, Smith J, Diven W, Penkrot RJ, Starzl TE. Rapid growth of an intact human liver transplanted into a recipient larger than the donor. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1414–1419. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90274-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla A, Zeng Q, Polimeno L, Carr BI, Sun D, Porter KA, Van Thiel DH, Starzl TE. Small-for-size liver transplantation into large recipient: a model of hepatic regeneration. Hepatology. 1994;19:210–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Tomita Y, Hirai R, Yamaoka K, Kaji K, Ichihara A. Inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor-β on DNA synthesis of adult rat hepatocytes in primary culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;133:1042–1050. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell WE, Coffey RJ, Jr, Ouellette AJ, Moses HL. Type β transforming growth factor reversibly inhibits the early proliferative response to partial hepatectomy in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5126–5130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Kanzaki M, Mashima H, Mine T, Kojima I. Norepinephrine reverses the effects of activin A on DNA synthesis and apoptosis in cultured rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1996;23:288–293. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu PP, Datto MB, Wang XF. Molecular mechanisms of transforming growth factor-β signaling. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:349–363. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Novoselov V, Celeste AJ, Wolfman NM, ten Dijke P, Kuehn MR. Nodal signaling uses activin and transforming growth factor-β receptor-regulated Smads. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:656–661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun L, Mead JE, Panzica M, Mikumo R, Bell GI, Fausto N. Transforming growth factor β mRNA increases during liver regeneration: a possible paracrine mechanism of growth regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1539–1543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Gallo J, Sozmen EG, Chytil A, Russell WE, Whitehead R, Parks WT, Holdren MS, Her MF, Gautam S, Magnuson M, Moses HL, Grady WM. Inactivation of TGF-β signaling in hepatocytes results in an increased proliferative response after partial hepatectomy. Oncogene. 2005;24:3028–3041. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oe S, Lemmer ER, Conner EA, Factor VM, Levéen P, Larsson J, Karlsson S, Thorgeirsson SS. Intact signaling by transforming growth factor β is not required for termination of liver regeneration in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1098–1105. doi: 10.1002/hep.20426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino H, Tateno C, Sato H, Yamasaki C, Katayama S, Kohashi T, Aratani A, Asahara T, Dohi K, Yoshizato K. A long-term culture of human hepatocytes which show a high growth potential and express their differentiated phenotypes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:184–191. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–83. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utoh R, Tateno C, Yamasaki C, Hiraga N, Kataoka M, Shimada T, Chayama K, Yoshizato K. Susceptibility of chimeric mice with livers repopulated by serially subcultured human hepatocytes to hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2008;47:435–446. doi: 10.1002/hep.22057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wack KE, Ross MA, Zegarra V, Sysko LR, Watkins SC, Stolz DB. Sinusoidal ultrastructure evaluated during the revascularization of regenerating rat liver. Hepatology. 2001;33:363–378. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hernandez A, Delgado FM, Amenta PS. The extracellular matrix in hepatic regeneration. Localization of collagen types I, III, IV, laminin, and fibronectin. Lab Invest. 1991;64:157–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppler D, Konig J. Hepatic canalicular membrane 5: expression and localization of the conjugate export pump encoded by the MRP2 (cMRP/cMOAT) gene in liver. FASEB J. 1997;11:509–516. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.7.9212074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos GK. Liver regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:286–300. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chari RS, Price DT, Sue SR, Meyers WC, Jirtle RL. Down-regulation of transforming growth factor beta receptor type I, II, and III during liver regeneration. Am J Surg. 1995;169:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M, Monga SP, Liu Y, Brodie SG, Tang Y, Li C, Mishra L, Deng CX. Smad proteins and hepatocyte growth factor control parallel regulatory pathways that converge on β1-integrin to promote normal liver development. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5122–5131. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5122-5131.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassiman D, Libbrecht L, Desmet V, Denef C, Roskams T. Hepatic stellate cell/myofibroblast subpopulations in fibrotic human and rat livers. J Hepatol. 2002;36:200–209. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00260-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniaris LG, McKillop IH, Schwartz SI, Zimmers TA. Liver regeneration. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:634–659. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patijn GA, Lieber A, Schowalter DB, Schwall R, Kay MA. Hepatocyte growth factor induces hepatocyte proliferation in vivo and allows for efficient retroviral-mediated gene transfer in mice. Hepatology. 1998;28:707–716. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Ma K, Zhang J, Qatanani M, Cuvillier J, Liu J, Dong B, Huang X, Moore DD. Nuclear receptor–dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science. 2006;312:233–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1121435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-β signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001;29:117–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeruss JS, Sturgis CD, Rademaker AW, Woodruff TK. Down-regulation of activin, activin receptors, and Smads in high-grade breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3783–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto N, Tateno C, Tachibana A, Utoh R, Morikawa Y, Shimada T, Momisako H, Itamoto T, Asahara T, Yoshizato K. GH enhances proliferation of human hepatocytes grafted into immunodeficient mice with damaged liver. J Endocrinol. 2007;194:529–553. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]