Abstract

To determine whether TLR9 signaling contributes to the development of the adaptive immune response to cryptococcal infection, wild-type (TLR9+/+) and TLR9 knockout (TLR9−/−) BALB/c mice were infected intratracheally with 104 C. neoformans 52D. We evaluated 1) organ microbial burdens, 2) pulmonary leukocyte recruitment, 3) pulmonary and systemic cytokine induction, and 4) macrophage activation profiles. TLR9 deletion did not affect pulmonary growth during the innate phase, but profoundly impaired pulmonary clearance during the adaptive phase of the immune response (a 1000-fold difference at week 6). The impaired clearance in TLR9−/− mice was associated with: 1) significantly reduced CD4+, CD8+ T cell, and CD19+ B cell recruitment into the lungs; 2) defects in Th polarization indicated by altered cytokine responses in the lungs, lymphonodes, and spleen; and 3) diminished macrophage accumulation and altered activation profile, including robust up-regulation of Arg1 and FIZZ1 (indicators of alternative activation) and diminished induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (an indicator of classical activation). Histological analysis revealed defects in granuloma formation and increased numbers of intracellular yeast residing within macrophages in the lungs of TLR9−/− mice. We conclude that TLR9 signaling plays an important role in the development of robust protective immunity, proper recruitment and function of effector cells (lymphocytes and macrophages), and, ultimately, effective cryptococcal clearance from the infected lungs.

C. neoformans is a leading cause of fatal mycosis in HIV-positive individuals around the globe. Incidence of C. neoformans infection is increasing in organ transplant recipients, patients with hematological malignancies, and those undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Cryptococcosis patients are affected predominantly by encapsulated strains of C. neoformans,1,2,3 while nonencapsulated strains are only rarely isolated from severely immunocompromised patients1,4,5,6 and can be cleared by the innate immune system in laboratory infection models.7,8,9

Lack of CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocytes is the most common trigger for progressive/persistent cryptococcosis in both patients and animal models of infection.10,11,12,13 The development of protective immunity in the lungs is associated with the arrival of effector T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) into the lungs, which coincides with positive delayed-type hypersensitivity reactivity to cryptococcal antigens.14,15 In contrast with the pivotal role of T cells, the role of B cells during C. neoformans clearance is less apparent.16,17,18,19,20,21

Successful clearance of C. neoformans is also associated with an adaptive Th1 immune response characterized by antigen driven production of type 1 cytokines (interferon [IFN]-γ and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α) and containment of C. neoformans within granuloma-like inflammatory infiltrates.22,23,24,25,26 In contrast, Th2 immune response characterized by type 2 cytokine production (interleukin [IL]-4, IL-5, and IL-13), pulmonary eosinophilia, increased airway resistance, and severe lung pathology is associated with uncontrolled growth of C. neoformans in the lungs.23,24,26,27,28,29,30

The final link in anticryptococcal host defense is classical activation of macrophages (CAM) that can occur as a consequence of Th1-derived signals.23,30,31,32 CAM are thought to be the major effector cells that can effectively destroy cryptococci. In contrast, alternatively activated macrophages (AAM) harbor C. neoformans.11,32,33,34 Generation of CAM/AAM has been postulated to be regulated by Th1/Th2 bias;11,22,23,30,33,35 however, differential activation of macrophages can also occur in response to other factors, such as stimulation of toll-like receptors (TLRs) by microbial products.36,37

TLRs have been found to be critical for immune recognition and clearance of viral, bacterial, protozoan, and fungal pathogens.38,39,40,41 The role of TLRs in anticryptococcal host defenses is not fully understood. While TLR2 and TLR4 have been shown to respond to C. neoformans products,42,43 their in vivo effects are minimal or highly inconsistent between different studies.44,45 TLR9 is a member of the TLR family located intracellularly in the cytoplasm and binding to cytoplasmic endosomes of dendritic cells (DC), macrophages, and other cells of the immune system.46 TLR9 coupling/signaling occurs presumably after the microbe becomes ingested and lysed within the endosome, exposing the CpG DNA (TLR9 ligand).47 Stimulation of TLR9 with microbial or synthetic CpGDNA enhances DC maturation and facilitates Th1 driving IL-12 production by these cells.36,41,48,49,50,51 Thus, TLR9 activation is thought to promote Th1 skewing and prevent Th2 skewing during the development of the adaptive immune responses. Previous studies indicated that TLR9 contributes to anticryptococcal host defenses.52,53,54 Synthetic CpGDNA co-administered during C. neoformans infection enhances the development of Th1 response and reduces C. neoformans burden.54 In addition, cooperative stimulation of DC by cryptococcal mannoproteins and CpG OligodN was demonstrated in vitro.53 Cryptococcal DNA and cell lysates have been shown to activate dendritic cell maturation and to induce IL-12 (pro-Th1 cytokine) production via TLR9 mediated mechanism in vitro.52 Furthermore, TLR9 contributes to the rapid/innate clearance of an acapsular mutant Cap67 in vivo.52

It remains unknown if TLR9 is required for the development of natural adaptive immunity to C. neoformans and if it would be required for clearance of clinically relevant (encapsulated) organisms. In the present study, we investigate the role of TLR9 on pulmonary clearance of strain 52D (24067, an encapsulated clinical isolate) and its effects on the effector adaptive immune mechanisms: 1) pulmonary lymphocyte accumulation, 2) immune polarization, and 3) recruitment/activation of macrophages. This is the first report to establish the requirement of TLR9 signaling for the development of adaptive anticryptococcal immunity and clearance of the encapsulated organism from the infected lungs.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female wild-type BALB/c mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). TLR9−/− mice were bred at the University of Michigan/Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center using micro-isolator cages covered with a filter top, with food/water provided ad libitum. Mice were aged to 8 to 10 weeks at the time of infection. At the time of data collection, mice were humanely euthanized by CO2 inhalation. All experiments were approved by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals and the Veterans Affairs Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

C. neoformans

C. neoformans strain 52D (ATCC 24067) was recovered from 10% glycerol frozen stocks stored at −80°C and grown to stationary phase at 36°C in Sabouraud dextrose broth (1% neopeptone, 2% dextrose; Difco, Detroit, MI) on a shaker. The cultures were then washed in nonpyrogenic saline (Travenol, Deerfield, IL), counted on a hemocytometer, and diluted to 3.3 × 105 yeast cells/ml in sterile nonpyrogenic saline.

Intratracheal Inoculation of C. neoformans

Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (ketamine/xylazine 100/6.8 mg/kg/body weight) and were restrained on a foam plate. A small incision was made through the skin covering the trachea. The underlying salivary glands and muscles were separated. Infection was performed by intratracheal injection of 30 μl (104 colony forming units [CFU]) via 30-gauge needle actuated from a 1 ml tuberculin syringe with C. neoformans suspension (3.3 × 105/ml). After inoculation, the skin was closed with cyanoacrylate adhesive, and the mice were monitored during recovery from the anesthesia.

Organ CFU Assay

For determination of microbial burden in the lungs, small aliquots of dispersed lungs were collected following the digest procedure. For determination of spleen and brain CFU, the spleens and brains were dissected using sterile instruments, placed in 2 ml of sterile water and homogenized. Series of 10-fold dilutions of the lung, spleen, and brain samples were plated on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates in duplicates in 10 μl aliquots and incubated at room temperature. C. neoformans colonies were counted 2 days later and the number of CFU was calculated on a per-organ base.

Lung Leukocyte Isolation

The lungs from each mouse were excised, washed in RPMI, minced with scissors, and digested enzymatically at 37°C for 30 minutes in 15 ml/mouse of digestion buffer [RPMI, 5% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY); 1 mg/ml Collagenase A (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN); and 30 μg/ml DNase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)] and processed as previously described.28,55 The cell suspension and tissue fragments were further dispersed by repeated aspiration through the bore of a 10 ml syringe and were centrifuged. Erythrocytes in the cell pellets were lysed by addition of 3 ml of NH4Cl buffer (0.829% NH4Cl, 0.1% KHCO3, and 0.0372% Na2EDTA, pH 7.4) for 3 minutes followed by a 10-fold excess of RPMI. Cells were resuspended and a second cycle of syringe dispersion and filtration through a sterile 100 μm nylon screen (Nitex, Kansas City, MO) was performed. The filtrate was centrifuged for 25 minutes at 1500 × g in the presence of 20% Percoll (Sigma) to separate leukocytes from cell debris and epithelial cells. Leukocytes pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of complete RPMI media, and enumerated on a hemocytometer following dilution in trypan blue (Sigma).

Lung-Associated Lymph Node Leukocyte Isolation

Individual lung-associated lymph nodes (LALN) were excised. To collect LALN leukocytes, nodes were dispersed using a 3 ml sterile syringe plunger and flushed through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) with complete media into a sterile tube, as described previously. After being centrifuged at 12,000 rpm/min for 10 minutes, the supernatant was removed and the cell pellets were saved at −70°C for gene expression analysis by real-time reverse transcription PCR.

Isolation of RNA from Adherence-Enriched Pulmonary Macrophages

Isolated pulmonary leukocytes (10 × 106 cells/ml) were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 1.5 hours. Plates were washed twice using PBS to remove all nonadherent and loosely adherent cells. Total RNA was collected from adherent cells and used for real-time reverse transcription and qPCR analysis.32

Pulmonary Cytokine Production

Isolated lung leukocytes were diluted to 5 × 106 cells/ml and were cultured in 24-well plates with 2 ml of complete RPMI medium at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours. Supernatants were separated from cells by centrifugation, collected, and frozen until tested. The cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12p70, IL-4, and IL-10 were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using DuoSet kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and OPT-EIA kits (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) following the manufacturer’s specifications. All plates were read on a Versamax plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Antigen-Specific Cytokine Production by Splenocytes

Spleens were excised and dispersed using a 3 ml sterile syringe plunger and flushed through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) with complete media. Isolated spleen cells were diluted to 5 × 106 cells/ml and were cultured in media alone or with heat-killed C. neoformans in a ratio of 1:2 in 24-well plates with 2 ml of complete RPMI medium at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Supernatants were stored and analyzed for cytokine levels as described above. The antigen-specific cytokine production was calculated as a net gain of cytokine level compared with unstimulated control of the same sample.

Visual Identification of Leukocyte Populations

Macrophages, neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes were visually counted in Wright-Giemsa-stained samples of lung cell suspensions cytospun onto glass slides. Samples were fixed/prestained for 2 minutes in a one-step methanol-based Wright-Giemsa stain (Harleco, EM Diagnostics, Gibbstown, NJ) and stained using steps two and three of the Diff-Quik stain. This modification of the Diff-Quik stain procedure improves the resolution of eosinophils from neutrophils. A total of 300 cells were counted for each sample from randomly chosen high power microscope fields. The percentages of leukocyte subsets were multiplied by the total number of leukocytes to give the absolute number of specific leukocyte subsets in the sample.

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was prepared using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScriptIII (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokine mRNA was quantified with SYBR Green-based detection using an MX 3000P system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Forty cycles of PCR (94°C for 15 seconds followed by 60°C for 30 seconds and 72°C for 30 s) were performed on a cDNA template. The mRNA levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels and relative expression shown as % of GAPDH.

Histology

Lungs were fixed by inflation with 1 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin, excised en bloc and immersed in neutral buffered formalin. After paraffin embedding, 5 μm sections were cut and stained with mucicarmine (for C. neoformans) and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were analyzed with light microscopy and microphotographs were taken using the Digital Microphotography system DFX1200 with ACT-1 software (Nikon Co, Tokyo, JAP).23,28,30 The C. neoformans organisms within macrophages were counted by enumeration of 400 cells/section in randomly selected high power fields using a double-blinded approach. The estimates of live and dead organism within macrophages were based on morphological appearance and intensity of mucicarmin stain.

Antibody Staining and Flow Cytometric Analysis

All staining reactions were performed according to the protocols. Data were collected on a FACS LSR2 flow cytometer using DIVA software and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., San Carlos, CA). A minimum of 30,000 cells were analyzed per sample. Initial gates were set based on light scatter characteristics to exclude debris, unlysed red blood cells, and cell clusters. In cell suspensions, leukocytes were stained with PB-labeled anti-CD45. The lymphocytes in the preselected CD45+ cell population were gated on forward and side scatter plots, and the subsets were identified using phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD8 (for Tc cells), APC-Cy7-labeled anti-CD4 antibodies (for Th cells), and PerCPCy5.5-labeled anti-CD19 (for B cells).

Calculations and Statistics

Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test for individual paired comparisons or t-test with Bonferoni adjustment, whenever multiple groups were compared. Means with P values of <0.05 were considered significantly different. All values are reported as means ± standard errors (SEM). Calculations were performed using Primer of Biostatistics software (Mc Graw-Hill, NY).

Results

TLR9 Gene Deletion Impaired Clearance of C. neoformans

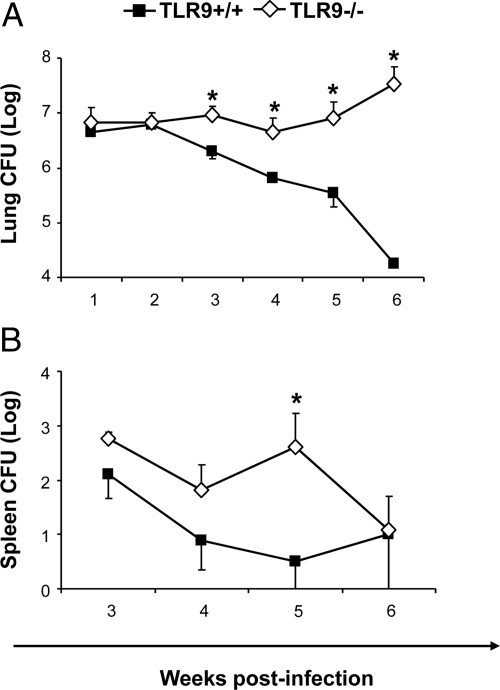

Our first objective was to assess the effect of TLR9 on pulmonary and extrapulmonary growth/clearance of C. neoformans in the infected mice. TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice were intratracheally inoculated with 104 cells of C. neoformans and pulmonary fungal burden was determined at 1 to 6 weeks postinfection (wpi). Identical C. neoformans growth pattern was observed in the lungs of TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice during the innate phase of the immune response (1000-fold increase from the inoculated load and “plateau” between 1 and 2 wpi, Figure 1A). Subsequently, differential clearance patterns between TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice were observed: a constant fungal burden of approximately 107 CFU persisted in the lungs of TLR9−/− mice, contrasting with gradual clearance observed in TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 1A). The dramatic difference in pulmonary fungal load (over three orders of magnitude at 6 wpi) indicated that TLR9 deletion severely impaired pulmonary clearance of C. neoformans during the adaptive phase of the immune response.

Figure 1.

Effect of TLR 9 deletion on fungal burdens in the lungs and spleens. TLR9+/+ and TLR9−/− mice were inoculated intratracheally with 104 C. neoformans 52D. A: The pulmonary fungal burden was evaluated at weekly intervals from 1 to 6 wpi. B: Spleen fungal burden was evaluated at 3, 4, 5, and 6 wpi. C. neoformans loads were evaluated via CFU assays performed on serially diluted samples. Data, pooled from three separate matched experiments, are shown as the mean log10 CFU per organ ± SEM. N = 10 and above for each of the analyzed time points; *P < 0.05 in comparison with the matching TLR9+/+ mouse result.

Apart from the lung, spleen and brain C. neoformans burdens were evaluated at 3, 4, 5 and 6 wpi as surrogates of extrapulmonary cryptococcal disease. The TLR9−/− mice demonstrated a trend toward increased spleen CFU at 3 and 4 wpi, significant elevation at week 5, but similar CFU at 6 wpi compared with TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 1B). Cerebral burdens were not detectable in either infected groups throughout the study. Thus, TLR9 was required for pulmonary clearance of C. neoformans, but had limited effect on extrapulmonary dissemination of C. neoformans.

TLR9 Gene Deletion Altered the Pulmonary Leukocyte Recruitment in C. neoformans-Infected Mice

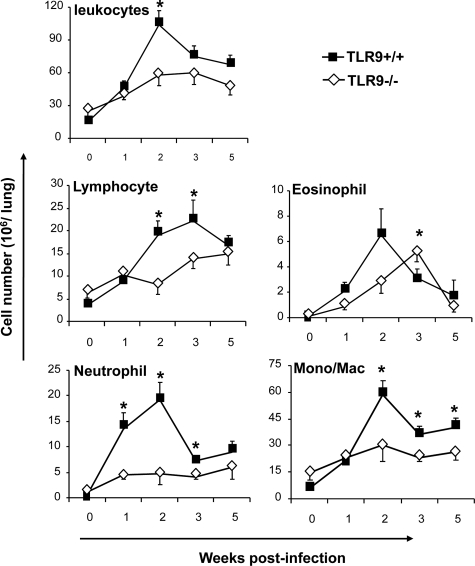

To determine whether the defect in fungal clearance in TLR9−/− mice was associated with changes in the magnitude and/or dynamics of inflammatory responses, we enumerated leukocytes in the infected lungs at 1, 2, 3, and 5 wpi. Both TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice developed significant inflammatory responses in the infected lungs compared with the uninfected controls (Figure 2). Although a significant difference in leukocyte numbers was found only at 2 wpi, a consistent trend of lower cell numbers in TLR9−/− versus TLR9+/+ mice lungs was noted throughout the study, indicating that the inflammatory response was less robust in the absence of TLR9. Furthermore, leukocyte numbers in the lungs of TLR9−/− mice were significantly decreased between 3 and 5 wpi, despite the persistently high fungal load.

Figure 2.

Effect of TLR9 deletion on magnitude of inflammatory response and recruitment of leukocyte subsets into the C. neoformans-infected lungs. Lungs were collected from uninfected (week 0) and C. neoformans-infected TLR9+/+ and TLR9−/− mice at 1, 2, 3, and 5 wpi and dispersed enzymatically. Leukocytes were isolated from individual mice and enumerated by a hemacytometer. Lung leukocyte subsets were assessed by microscopic evaluation of relative frequencies on stained cytospun slides analyzed under the microscope and calculated (see Materials and Methods). Data, pooled from three parallel experiments, are shown as the mean number ± SEM. N = 3 for uninfected controls and at least ten for infected mice at each of the analyzed time points; *P < 0.05 in comparison with the matching TLR9+/+ mouse result.

Differential cell count analysis revealed a significant effect of TLR9 deletion on major leukocyte subpopulations. Lymphocytes, the most essential component of the adaptive immune response, were significantly diminished in TLR9−/− mice at 2 and 3 wpi compared with the TLR9+/+ controls (Figure 2), suggesting a less vigorous adaptive immune response and consistent with the decreased fungal clearance in TLR9−/− mice. The differences in pulmonary granulocyte populations could reveal possible changes in the immunophenotype of the immune response. Persistent pulmonary eosinophilia is a hallmark of a Th2 response in cryptococcal infection,28,56 while chronic neutrophil presence may mark a Th17-driven response in the lungs.32 Although small but significant increase in pulmonary eosinophil recruitment was found at 3 wpi in TLR9−/− mice compared with TLR9+/+ mice, this difference was transient and represented temporal difference in the timing of the peak eosinophil recruitment (Figure 2). In contrast, a strong decrease in neutrophil recruitment at 1, 2, and 3 wpi was found in TLR9−/− mice compared with TLR9+/+ mice. The numbers of pulmonary mononuclear myeloid cells were also significantly decreased in TLR9−/− compared with robust recruitment of these cells in TLR9+/+ mice at 2, 3, and 5 wpi. In summary, TLR9−/− mice developed less vigorous inflammatory response and showed a different composition of inflammatory cells compared with TLR9+/+ mice, suggesting that the deletion of TLR9 affected multiple elements of the cellular immune response.

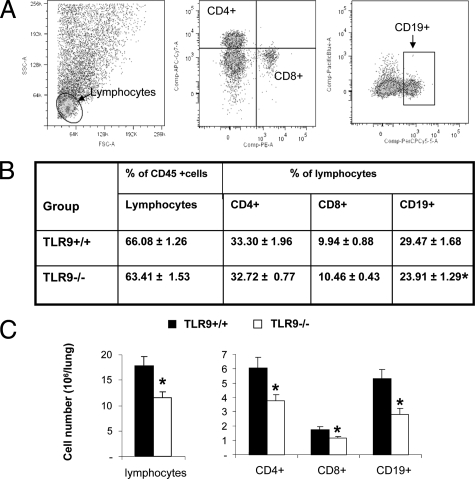

TLR9 Gene Deletion Decreased Pulmonary Accumulation of CD4+, CD8+ T Cells and CD19+ B Cells

The adaptive immune responses are orchestrated by T and B lymphocytes. These populations were analyzed to further identify the effect of TLR9 deletion on adaptive immunity. Frequencies and total numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell and CD19+ B cells were evaluated by flow cytometry at 3 wpi (Figure 3, Materials and Methods). Figure 3A demonstrates representative plots of anti-CD8, -CD4, and -CD19 antibody stains. Although no difference in relative frequency of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell in total CD45+ leukocyte pool were observed (Figure 3B), total numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were significantly lower in TLR9−/− mice compared with TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 3C). In contrast, both percentages (Figure 3B) and total numbers (Figure 3C) of B cells were significantly diminished in the lungs of TLR9−/− compared with TLR9+/+ mice. Thus, TLR9 deletion resulted in decreased pulmonary accumulation of all CD4+, CD8+, and CD19+ lymphocyte subsets with the most profound effect on B-cell (CD19+) subpopulation. Similar results were observed at 2 and 4 wpi for all three lymphocyte subsets (data not shown), indicating that this defect was persistent.

Figure 3.

Effect of TLR9 deletion on lymphocyte subsets in the C. neoformans-infected lungs. Lung leukocytes were isolated from C. neoformans-infected TLR9+/+ and TLR9−/− mice at 3 wpi. A: Frequency of lymphocyte subsets were determined by staining samples with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific for CD4+, CD8+, and CD19+ lymphocytes. B: Mean frequencies of lymphocytes in total lung leukocyte isolate (CD45+) population and CD4+, CD8+, and CD19+ in a lymphocyte subsets. C: Total numbers of CD4+, CD8+, and CD19+ lymphocytes/lung. Representative plots out of two separate experiments were shown. N = 7 and above for the quantitative data; *P < 0.05 in comparison with the matching TLR9+/+ mouse result.

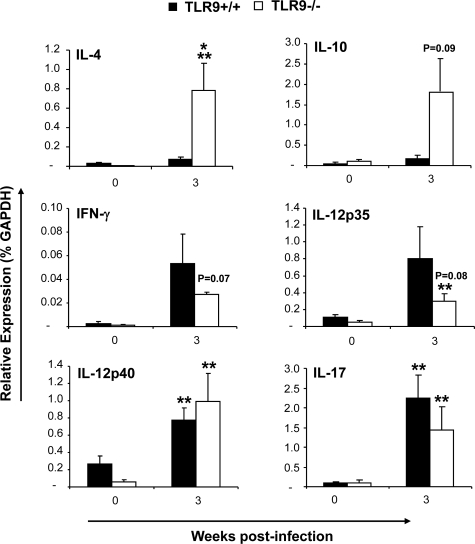

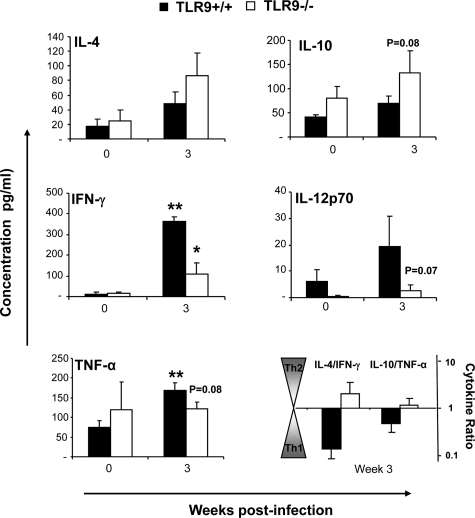

TLR-9 Gene Deletion Resulted in a Mixed Th1, Th2, and Th17 Cytokine Response in Lung Leukocytes in C. neoformans-Infected Lungs

The changes in granulocyte populations suggested that TLR9 deletion affected cytokine milieu during the adaptive phase of the immune response in the lungs. We examined cytokine profiles in pulmonary leukocyte isolates to evaluate this effect. We quantified mRNA expression for IL-4 and IL-10 (nonprotective Th2 and/or regulatory responses); IFN-γ, IL-12p35 and IL-12p40 (associated with protective Th1 response); and IL-17 (associated with Th17 response) at 3 wpi. We did not observe significant up-regulation of Th2 cytokines mRNA in the infected lungs of TLR9+/+ mice, while TLR9−/− mice showed notable up-regulation of IL-4 and IL-10 mRNA (Figure 4). The difference between TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice was significant for Th2 driving cytokine IL-4 and nearly significant for IL-10 (Figure 4). Both TLR9+/+ mice and TLR9−/− mice demonstrated up-regulation of mRNA for Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and pro-Th1 IL-12 at 3 wpi. The increases in IFN-γ and IL-12p35 mRNA expression were less pronounced, but not significantly lower in the absence of TLR9 (Figure 4). In addition, infected TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice showed similar elevation of IL-17 mRNA induction compared with their uninfected controls. Subsequently, the levels of secreted IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-12p70, and TNF-α protein in 24 hours lung-leukocyte culture supernatants were evaluated by ELISA (Figure 5). The effects of TLR9 deletion on secreted cytokine concentrations were comparable with the trends observed for mRNA expression (Figure 4–5). TLR9 gene deletion resulted in a trend to increase the Th2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10), and significantly lower production of Th1-driving/protective cytokine IFN-γ (Figure 5). A strong decreasing trend of IL-12p70 and TNF-α induction was also noted at 3 wpi (Figure 5). Because the trends to decrease protective (IL-12 and TNF-α) and increasing nonprotective (IL-4 and IL-10) cytokine responses in TLR9−/− mice were frequently close to the threshold of significance, but not achieving significant difference, the ratios between IL-4/IFN-γ and IL-10/TNF-α were calculated to determine whether pulmonary cytokine responses were shifted in the opposite directions (Figure 5). The change of these ratios from <1 (indicator of a protective Th1 balance) in TLR9+/+ mice to >1 in TLR9−/− mice illustrates a shift away from a protective Th1 response toward nonprotective Th2 following TLR9 deletion. Collectively, our PCR and protein cytokine data indicate that TLR9 signaling contributed to optimal Th1 cytokine polarization in the infected lungs during the adaptive phase of the immune response to C. neoformans.

Figure 4.

Effect of TLR9 deletion on cytokine mRNA expression pattern in leukocytes isolated from C. neoformans infected lungs. Lung leukocytes were isolated from uninfected (week 0) and infected TLR9+/+ and TLR9−/−mice at 3 wpi. Total leukocyte RNA was extracted, converted to cDNA, and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for the expression of selected “polarizing” cytokines. The values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and were expressed as relative gene expression ± SEM. Data were pooled from two parallel experiments. N = 3 for uninfected controls and at least seven for infected mice at each of the analyzed time points. For the comparisons between TLR9+/+ versus TLR9−/− mice, *P < 0.05, or the appropriate P value is listed above the bars; **P < 0.05 in comparison with the respective uninfected control mouse result.

Figure 5.

Effect of TLR9 deletion on cytokine protein production by leukocytes isolated from C. neoformans-infected lungs. Lung leukocytes were isolated from uninfected (week 0) and infected mice at 3 wpi and cultured for 24 hours at 5 × 106 cells/ml. Cytokine levels were evaluated by ELISA in cell culture supernatants. Bars represent mean cytokine concentration ± SEM (pg/ml). Data were pooled from two parallel experiments. N = 3 for uninfected controls and at least 6 for infected mice at each of the analyzed time points. For the comparisons between TLR9+/+ versus TLR9−/− mice, *P < 0.05, or the appropriate P value is listed above the bars; **P < 0.05 in comparison with the respective uninfected control mouse result.

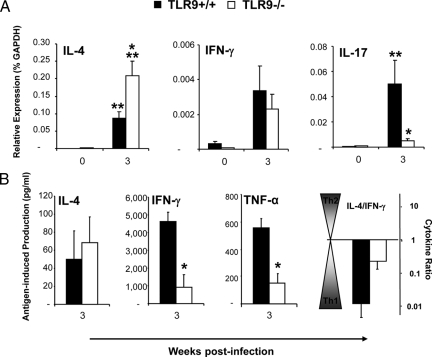

TLR-9 Gene Deletion Promoted Th2 and Inhibited Th17 Cytokine Polarization in the Pulmonary Draining Nodes in C. neoformans-Infected Lungs

Our next objective was to evaluate if the changes in the pulmonary immune response were paralleled by changes of the immune polarization in LALN from the infected mice. Consistent with the changes in mRNA expression in Th2/Th1 cytokine polarization observed in the lung leukocytes, TLR9 deletion resulted in significant upregulation of Th2-driving cytokine IL-4 mRNA in LALN (Figure 6A). Additionally, TLR9 deletion significantly attenuated IL-17 induction that was observed in TLR9+/+ mice at 3 wpi (Figure 6A), suggesting that TLR9 signaling contributed to the generation of the Th17 arm of the immune response within the LALN. Thus, our LALN data demonstrate that TLR9 is required for optimal Th polarizing cytokine profile in the pulmonary nodes.

Figure 6.

Effect of TLR9 deletion on pulmonary lymph node and spleen polarization. A: Pulmonary lymph nodes were collected from uninfected (week 0) and infected TLR9+/+ and TLR9−/−mice at 3 wpi. Total RNA was extracted, converted to cDNA, and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for the expression of selected “polarizing” cytokines. The values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and were expressed as relative mRNA expression ± SEM. Data were pooled from two parallel experiments. N = 2 for uninfected controls and 7 for infected mice; *P < 0.05 in comparison with the respective TLR9+/+ result. B: Splenocytes from each infected mouse were isolated, diluted to 5 × 106 cells/ml, and cultured with/without heat killed C.neoformans in a ratio of 1:2 in 24-well plates with 2 ml of complete RPMI medium at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 48 hours. Cytokine levels were evaluated by ELISA in cell culture supernatants. The antigen-specific cytokine production was calculated as a net gain of cytokine level compared with unstimulated control of the same sample. The values were shown as cytokine concentration ± SEM (pg/ml). N = 5 for infected mice. *P < 0.05 in comparison with the matching TLR9+/+ mouse result; **P < 0.05 in comparison with the respective uninfected control mouse result.

TLR-9 Gene Deletion Results in Decreased Antigen-Specific Systemic Production of Th1 Cytokines

Alteration of pulmonary Th2/Th1 cytokine profiles in C. neoformans infected TLR9−/− mice could be linked to effects on either local and/or systemic immune polarization. To address this point, we evaluated antigen-specific cytokine production by splenocyte cultures (pulsed with heat killed Cryptococcus). TLR9 deletion caused a significant decrease in cryptococcal antigen-induced IFN-γ and TNF-α production by splenocytes from TLR9−/− mice compared with TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 6B). The induction of IL-4 protein was not significantly altered. The ratio of IL-4/IFN-γ increased but did not shift above 1 in TLR9−/−mice (Figure 6B), suggesting that the deletion of TLR9 resulted in a less pronounced Th1 response to cryptococcal antigen at the systemic level, but did not induce a switch to a systemic Th2 response.

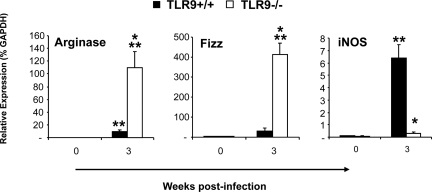

TLR9 Gene Deletion Prevented CAM and Promoted AAM in C. neoformans-Infected Lungs

Macrophages/monocytes are the ultimate effectors of the adaptive anticryptococcal immune response. Protective immunity is marked by CAM, while AAM occurs during nonprotective responses. To determine whether TLR9 gene deletion altered macrophage activation pattern, the expression of AAM hallmark genes arginase (Arg1) and the protein found in inflammatory zone 1 (Fizz1) and the CAM hallmark gene inducible nitric oxide synthase were analyzed in adherence enriched pulmonary macrophages at 3 wpi (Figure 7). Macrophages from TLR9−/− mice showed strong up-regulation of Arg1 and Fizz1 genes but a near-baseline level of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression, consistent with a polarized AAM phenotype (Figure 7). In contrast, macrophages from infected TLR9+/+ mice showed robust upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene but near-baseline levels of Arg1 and Fizz1 gene expression, consistent with a polarized CAM phenotype. Thus, TLR9 deletion profoundly affected macrophage phenotype in C. neoformans infected lungs, resulting in a switch from CAM to AAM.

Figure 7.

Effect of TLR9 deletion macrophages activation profile in C. neoformans infected lungs. Lung leukocytes were isolated from uninfected (week 0) and infected TLR9+/+ and TLR9−/− mice at 3 wpi. Macrophage population was enriched by 90-minute adherence and removal of nonadherent cells. RNA was extracted and analyzed as described above to quantify alternative (Arg1 and Fizz1) versus classical (inducible nitric oxide synthase) macrophage activation gene expression. The values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and were expressed as relative gene expression ± SEM. Data were pooled from three separate matched experiments. N = 3 for uninfected mice and at least nine for each of the analyzed time points. *P < 0.05 in comparison with the matching TLR9+/+ mouse result; **P < 0.05 in comparison with the respective uninfected control mouse result.

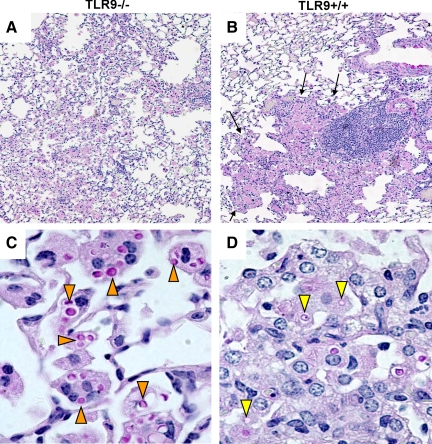

TLR9 Deletion Altered Pathological Findings in C. neoformans-Infected Lungs

To determine whether TLR9 deletion resulted in more profound pathological alterations in the lungs post-C. neoformans infection, histopathological examination of infected lungs at 6 wpi was performed (Figure 8). Leukocytes in the lungs of TLR9−/− mice formed loose infiltrates encompassing wide-spread areas of the lungs, without forming defined lesions (Figure 8A). In contrast, the infected lungs of TLR9+/+ mice presented tight consolidated inflammatory lesions, clearly marginalized from the uninfected lung portions (Figure 8B). The areas containing dense mononuclear/lymphoid cell infiltrates were surrounded by layers of larger cells (macrophages), consistent with well-organized Th1 granuloma formation in the lungs of TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 8B). The high power images of infected lungs in TLR9−/− mice revealed large number of yeast cells stained strongly with mucicarmine, indicating viable C. neoformans organisms residing within enlarged macrophages. Fewer yeasts presented weak mucicarmin staining/translucent appearance, consistent with organisms degraded by macrophages. Microscopic counts revealed 222.17 ± 25.69 intracellular organisms that appeared intact and 38.83 ± 7.23 degraded organisms per 100 macrophages in TLR9−/− mice, suggesting that the majority of internalized organisms were surviving within macrophages (Figure 8C). In contrast, significantly fewer (P < 0.001) organisms were found within the lung macrophages of TLR9+/+ mice and the majority of these microbes appeared degraded; only 9 ± 3.88 organisms appeared intact while 29.33 ± 7.99 were degraded per 100 macrophages, Figure 8D). Thus, our histological data further supported our findings and indicated that the inadequate immune response, failure of granuloma formation, severe alteration of macrophage activation and the impaired intracellular killing of C. neoformans were responsible for impaired clearance of C. neoformans in the absence of TLR9 signaling.

Figure 8.

Effect of TLR9 deletion on morphological pattern of pulmonary inflammation and pathological lesions in C. neoformans infected lungs. Lungs from infected TLR9−/− and TLR9+/+ mice were perfused with buffered formalin, fixed, and processed for histology at 6 wpi. Representative photomicrographs of H&E + mucicarmine stained slides taken at 10× (A, B) and 40× (C, D) objective power. Note that numerous C. neoformans organisms are widespread in the lungs of TLR9−/− mice loose leukocyte infiltrate extended into the wide areas (A) and fewer cryptococcal cells contained in dense inflammatory infiltrates and a clear margin between healthy and sick section (arrows, B). The high power images (bottom) show enlarged macrophages harboring multiple cryptococcal cells (orange pointers) in TLR9−/− mice lungs (C) and smaller macrophages with remnants of ingested/degraded yeasts (yellow pointers) in TLR9+/+ mice (D).

Discussion

Our study shows that deletion of TLR9 during C. neoformans infection resulted in: 1) impaired clearance of C. neoformans from the infected lungs during the adaptive but not innate phase of the immune response; 2) diminished accumulation of CD4+, CD8+ T cells, and CD19+ B cells in the infected lungs; 3) deviation in cytokine response involving Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines; 4) a switch from the protective CAM to a nonprotective AAM phenotype; and 5) defective granuloma formation in the infected lungs and evidence of decreased cryptococcal killing by macrophages. This is the first demonstration that TLR9 is required for development/execution of protective immunity against C. neoformans in vivo.

Previous studies showed that TLR9 signaling contributes to the in vitro responses of dendritic cells and macrophages stimulated by C. neoformans and its products.52,54 A modest but statistically significant effect of TLR9 on the innate clearance of an acapsular C. neoformans mutant Cap67 (0.5 log at 2 wpi) was also reported in a mouse model of pulmonary infection.52 The present study evaluated the effects of TLR9 in a mouse model of pulmonary infection with the clinical isolate C. neoformans 52D. In contrast with the previous studies that used an acapsular mutant in vivo,52 TLR9 had no effect on fungal burden during the early/innate response in our model (first 2 wpi).57 However, TLR9 was required for clearance during the effector phase of the adaptive immune response (from 3 wpi onwards) (Figure 1A). Comparison of previously reported effects of TLR9 in Cap67 infection model with the present study signifies that TLR9 is important in both innate and adaptive phases of anticryptococcal host defenses. However, when C. neoformans elimination requires strong, adaptive immunity (clinically relevant, encapsulated strains), TLR9 predominantly supports the efficient, adaptive clearance of the microbe.

Our results demonstrate that TLR9 is required for optimal lymphocyte influx into the lungs, among which most crucial are antigen specific effector T cells.12,13 The decreased lymphocyte number in the infected TLR9−/− lungs persisted throughout the course of the adaptive immune response and encompasses all CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells (Figure 3), consistent with a significantly weaker adaptive immune response. This outcome suggests that TLR9 signaling is needed for optimal T-cell and B-cell proliferation/survival in C. neoformans infected mice, just as reported in previous studies in which TLR9 was required for T- and B-cell proliferative responses to other antigens in vitro58,59 and for the adaptive T-cell mediated responses to T. cruzi infection in vivo.60

Apart from the major effects on pulmonary lymphocyte populations, we observed that TLR9 is required for optimal Th1 immune polarization. Absence of TLR9 resulted in an elevation of Th2 elements (IL-4 mRNA in the lung and LALN, and eosinophilia at 3 wpi) and decreased Th1 elements (secretion of IFN-γ by lung leukocytes and IFN-γ and TNF-α responses to cryptococcal antigen stimulation of splenocytes) in C. neoformans-infected mice. We also observed reduced IL-17 induction in the LALN and reduced numbers of neutrophils in the infected lungs in the absence of TLR9, suggesting that TLR9 may also benefit the development of a Th17-arm in cryptococcal infection. This is consistent with a pro-Th17 role for TLR9 found in Mycobacteria infection.61 Interestingly, the effect on cytokine responses was frequently “borderline” in terms of statistical significance, contrasting with the major changes characterizing a switch to a Th2 response previously observed in IFN-γ−/− or CCR2−/− mice infected with C. neoformans.11,26 Thus, on one hand, the importance of endogenous TLR9 signaling for optimal development of Th1 is consistent with the overall pro-Th1 role of TLR9 signaling reported by other studies.41 On the other hand, the effect on cytokine profile is less pronounced than we would expect with the level of defect in cryptococcal clearance found in this study. One possibility of such an outcome is that cumulative small changes in multiple cytokines resulted in “immunological stalemate,” like the one observed in response to early TNF-α signal disruption.62 Another possibility is that the defect in C. neoformans clearance in TLR9−/− mice was not predominantly due to suboptimal polarization of the pulmonary immune response, but was caused by a defect in another effector mechanism.

The most distal effector mechanism in C. neoformans clearance ie, recruitment and activation status of mononuclear phagocytes. We observed that mononuclear phagocyte numbers were significantly decreased in TLR9−/− mice lungs at 2, 3, and 5 wpi compared with TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 2). Apart from the nearly 50% reduction in macrophage/monocytes in TLR9−/− mice, their activation pattern showed a dramatic shift from classically activated (CAM) to alternatively activated (AAM) macrophages (Figure 7). Compared with the quite modest effect of TLR9 deletion on lymphocyte numbers and immune polarization, the dramatic changes in molecular hallmarks of differential macrophage activation demonstrate that TLR9 plays a major role in the fate of a CAM versus AAM phenotype. This strong effect most likely resulted from both the altered cytokine milieu known to have major role on macrophage phenotype11,63,64,65 and the direct role of TLR9 activation in classical macrophage activation, as reported in acute Legionella infection.48 Gene expression pattern (Figure 7), and intracellular presence of C. neoformans within macrophages was consistently shown in the present (Figure 8D) and previous studies,11,32,34,65 further supporting the notion that AAM provide a niche for cryptococcal growth/persistence in different pathophysiological circumstances. In summary, the requirement of TLR9 signaling for the classical activation of macrophages appears to be the most distal effect by which TLR9 facilitates protective immune response and clearance of C. neoformans from the infected lungs.

Recruitment of lymphocytes and mononuclear phagocytes (antigen specific DTH reaction)66 is crucial for the formation of granulomas/pseudogranulomas, which contain Cryptococci within the infected portions of the lungs.31,67,68 Formation of these tight infiltrates/granulomas during vigorous Th1 immune responses in C. neoformans infected lungs has been well documented by our group as well as others.23,30,31,68 Proximity of T cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages in these infiltrates facilitates interactions between these cells which are thought to be essential for optimal activation of these cells needed for efficient clearance of C. neoformans.13,31,67,68 Histopathological findings in the lungs of TLR9−/− mice demonstrate mononuclear infiltrates with a loose structure (Figure 8A), strongly contrasting with the well organized, dense, granuloma-like infiltrates in the lungs of TLR9+/+ mice (Figure 8B). This provides evidence that TLR9 plays an important role in Th1 granuloma formation in C. neoformans infected lungs, just as it does in Mycobacteria and mycobacterial antigen challenged lungs.61,69

In terms of the upstream mechanism by which TLR9 affected multiple aspects of the adaptive immune response to C. neoformans, previous studies have demonstrated that TLR9 signaling is required for the dendritic cell responses to C. neoformans DNA, specifically for IL-12p40 production and the induction of CD40 co-stimulatory molecule in vitro.52 However, our studies did not detect a major defect in IL-12 production by lung leukocytes at 3 wpi (Figure 3 and 4) or at the earlier time points (Olszewski lab, preliminary data). Therefore, it is unlikely that the defect in IL-12 production could be the sole mechanism for the changes we observe in vivo. Future studies will be needed to critically evaluate the in vivo effects of TLR9 deletion on dendritic cells and the major effector cells (T cells and macrophages).

Despite the strong effect on pulmonary C. neoformans clearance (Figure 1A), TLR9 does not appear to be important for the control of cerebral fungal burdens. However, CNS dissemination of moderately virulent strain 52D occurs only when the infected animals become severely immunocompromised.26,70 Thus, the immunological defect in the absence of TLR9 was most likely not severe enough to influence CNS dissemination. Furthermore, the dynamics of pulmonary clearance is not always directly related to the rate of CNS dissemination. Our previous studies demonstrated that highly virulent strain H99 disseminates to the CNS, even while being cleared from the lungs of IL-4/IL-13−/− mice.32

Treatment of cryptococcosis is complicated by several factors: 1) suboptimal numbers of T cells in the majority of infected patients72; 2) increasing cryptococcal resistance to antifungal drugs71,72; and 3) the ability of C. neoformans to persist in a latent form,73 possibly within infected macrophages.74,75 These factors increase the risk of reoccurrence of cryptococcosis following successful treatment.72 Our in vivo studies show that TLR9 activation enhanced lymphocyte recruitment, benefited Th1 polarization and Th1-response to cryptococcal antigen, and prevented alternative activation of macrophages. These effects of TLR9 activation would be therapeutically beneficial to cryptococcosis patients. In fact, synthetic CPGODN (TLR9 ligands) have been shown to enhance C. neoformans clearance and protection from detrimental Th2 bias in an animal model.54 Together, both of these studies highlight the importance of future clinical trials that would establish if such treatment improves the rate of immune reconstitution and efficiency of antifungal therapies and decreases the risk of reoccurrence of cryptococcosis in immune compromised patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gwo-hsiao Chen, Dr. Jami Milam, and Dr. John Osterholzer for their help in different phases of this project. We would like to acknowledge technical assistance of Alexandra Banks, Jana Jacobs, Aditya Jain, Christian Love, Daniel Lyons, Andrew McNamara, Daniel Meister, Kristin Tompkins, and Stuart Zeltzer. We thank the Undergraduate Research Opportunity program at the University of Michigan for support undergraduate students working in our laboratory.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Michal A. Olszewski, D.V.M., Ph.D., Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Health System (11R), 2215 Fuller Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48105. E-mail: olszewsm@umich.edu.

Supported in part by Merit Review grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (M.A.O. and G.B.T.), R01-HL51082 (G.B.T.), NHLBI HL97456 and HL25243 (T.J.S.), K08-HL094762 (U.B.), and R01-HL63670 and R01-HL65912 (G.B.H.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Y.Z. and F.W. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Bottone EJ, Toma M, Johansson BE, Wormser GP. Capsule-deficient Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS patients. Lancet. 1985;1:400. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91422-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa MM, Lazera MS, Barbosa GG, Trilles L, Balassiano BR, Macedo RC, Bezerra CC, Perez MA, Cardarelli P, Wanke B. Serotyping of 467 Cryptococcus neoformans isolates from clinical and environmental sources in Brazil: analysis of host and regional patterns. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:73–77. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.73-77.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect JR. Cryptococcus neoformans: a sugar-coated killer with designer genes. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2005;45:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attal HC, Grover S, Bansal MP, Chaubey BS, Joglekar VK. Capsule deficient Cryptococcus neoformans an unusual clinical presentation. J Assoc Physicians India. 1983;31:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bava J, Solari R, Isla G, Troncoso A. Atypical forms of Cryptococcus neoformans in CSF of an AIDS patient. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2:403–405. doi: 10.3855/jidc.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie DW, Hay RJ. Capsule-deficient Cryptococcus neoformans in AIDS patients. Lancet. 1985;1:642. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barluzzi R, Brozzetti A, Delfino D, Bistoni F, Blasi E. Role of the capsule in microglial cell-Cryptococcus neoformans interaction: impairment of antifungal activity but not of secretory functions. Med Mycol. 1998;36:189–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromtling RA, Shadomy HJ, Jacobson ES. Decreased virulence in stable, acapsular mutants of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycopathologia. 1982;79:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00636177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder JA, Olson GK, Chang YC, Kwon-Chung KJ, Lipscomb MF. Complementation of a capsule deficient Cryptococcus neoformans with CAP64 restores virulence in a murine lung infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:306–314. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.3.4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffnagle GB, Lipscomb MF, Lovchik JA, Hoag KA, Street NE. The role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the protective inflammatory response to a pulmonary cryptococcal infection. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:35–42. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, Hernandez Y, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Role of IFN-gamma in regulating T2 immunity and the development of alternatively activated macrophages during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:6346–6356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell DM, Moore TA, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Generation of antifungal effector CD8+ T cells in the absence of CD4+ T cells during Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:7920–7928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindell DM, Moore TA, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Distinct compartmentalization of CD4+ T-cell effector function versus proliferative capacity during pulmonary cryptococcosis. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:847–855. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan KL, Murphy JW. Kinetics of cellular infiltration and cytokine production during the efferent phase of a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Immunology. 1997;90:189–197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan KL, Fidel PL, Jr, Murphy JW. Effects of Cryptococcus neoformans-specific suppressor T cells on the amplified anticryptococcal delayed-type hypersensitivity response. Infect Immun. 1991;59:29–35. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.1.29-35.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre KM, Johnson LL. A role for B cells in resistance to Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:525–530. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.525-530.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung PY, Murphy JW. In vitro interactions of immune lymphocytes and Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1982;36:1128–1138. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.3.1128-1138.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchiarelli A. The cellular responses induced by the capsular polysaccharide of Cryptococcus neoformans differ depending on the presence or absence of specific protective antibodies. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:413–420. doi: 10.2174/1566524054022585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenhouwer DO, Shapiro S, Feldmesser M, Casadevall A, Scharff MD. Both Th1 and Th2 cytokines affect the ability of monoclonal antibodies to protect mice against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6445–6455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6445-6455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitta RW, Datta K, Chang Q, Luo RX, Witover B, Subramaniam K, Pirofski LA. Protective and nonprotective human immunoglobulin M monoclonal antibodies to Cryptococcus neoformans glucuronoxylomannan manifest different specificities and gene use profiles. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4810–4818. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4810-4818.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torosantucci A, Chiani P, Bromuro C, De Bernardis F, Palma AS, Liu Y, Mignogna G, Maras B, Colone M, Stringaro A, Zamboni S, Feizi T, Cassone A. Protection by anti-beta-glucan antibodies is associated with restricted beta-1,3 glucan binding specificity and inhibition of fungal growth and adherence. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GH, McDonald RA, Wells JC, Huffnagle GB, Lukacs NW, Toews GB. The gamma interferon receptor is required for the protective pulmonary inflammatory response to Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1788–1796. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1788-1796.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GH, McNamara DA, Hernandez Y, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Olszewski MA. Inheritance of immune polarization patterns is linked to resistance versus susceptibility to Cryptococcus neoformans in a mouse model. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2379–2391. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01143-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decken K, Kohler G, Palmer-Lehmann K, Wunderlin A, Mattner F, Magram J, Gately MK, Alber G. Interleukin-12 is essential for a protective Th1 response in mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4994–5000. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4994-5000.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovchik JA, Lyons CR, Lipscomb MF. A role for gamma interferon-induced nitric oxide in pulmonary clearance of Cryptococcus neoformans. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:116–124. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.1.7598935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor TR, Kuziel WA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. CCR2 expression determines T1 versus T2 polarization during pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:2021–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Hossain Qureshi M, Zhang T, Koguchi Y, Xie Q, Kurimoto M, Saito A. Interleukin-4 weakens host resistance to pulmonary and disseminated cryptococcal infection caused by combined treatment with interferon-gamma-inducing cytokines. Cell Immunol. 1999;197:55–61. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Huffnagle GB, McDonald RA, Lindell DM, Moore BB, Cook DN, Toews GB. The role of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha/CCL3 in regulation of T cell-mediated immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2000;165:6429–6436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Y, Arora S, Erb-Downward JR, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Distinct roles for IL-4 and IL-10 in regulating T2 immunity during allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:1027–1036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain AV, Zhang Y, Fields WB, McNamara DA, Choe MY, Chen GH, Erb-Downward J, Osterholzer JJ, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA. Th2 but not Th1 immune bias results in altered lung functions in a murine model of pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5389–5399. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00809-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison S, Ravi S, Wozniak K, Young M, Olszewski M, Wormley F. Pulmonary infection with an interferon-gamma producing cryptococcus neoformans strain results in classical macrophage activation and protection. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:774–785. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang F, Tompkins KC, McNamara A, Jain AV, Moore BB, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB, Olszewski MA. Robust Th1 and Th17 immunity supports pulmonary clearance but cannot prevent systemic dissemination of highly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans H99. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2489–2500. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Stenzel W, Kohler G, Werner C, Polte T, Hansen G, Schutze N, Straubinger RK, Blessing M, McKenzie AN, Brombacher F, Alber G. IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2007;179:5367–5377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholzer JJ, Surana R, Milam JE, Montano GT, Chen GH, Sonstein J, Curtis JL, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB, Olszewski MA. Cryptococcal urease promotes the accumulation of immature dendritic cells and a non-protective T2 immune response within the lung. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:932–943. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Stenzel W, Kohler G, Polte T, Blessing M, Mann A, Piehler D, Brombacher F, Alber G. A gene-dosage effect for interleukin-4 receptor alpha-chain expression has an impact on Th2-mediated allergic inflammation during bronchopulmonary mycosis. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1714–1721. doi: 10.1086/593068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Kasmi KC, Qualls JE, Pesce JT, Smith AM, Thompson RW, Henao-Tamayo M, Basaraba RJ, Konig T, Schleicher U, Koo MS, Kaplan G, Fitzgerald KA, Tuomanen EI, Orme IM, Kanneganti TD, Bogdan C, Wynn TA, Murray PJ. Toll-like receptor-induced arginase 1 in macrophages thwarts effective immunity against intracellular pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1399–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu S, Bhat SQ, Kumar NP, Anuradha R, Kumaran P, Gopi PG, Kolappan C, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. Attenuation of toll-like receptor expression and function in latent tuberculosis by coexistent filarial infection with restoration following antifilarial chemotherapy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutzik SR, Tan B, Li H, Ochoa MT, Liu PT, Sharfstein SE, Graeber TG, Sieling PA, Liu YJ, Rea TH, Bloom BR, Modlin RL. TLR activation triggers the rapid differentiation of monocytes into macrophages and dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun HS, Aosai F, Norose K, Chen M, Piao LX, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Ishikura H, Yano A. TLR2 as an essential molecule for protective immunity against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1081–1087. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou Fakher FH, Rachinel N, Klimczak M, Louis J, Doyen N. TLR9-dependent activation of dendritic cells by DNA from Leishmania major favors Th1 cell development and the resolution of lesions. J Immunol. 2009;182:1386–1396. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yauch LE, Mansour MK, Levitz SM. Receptor-mediated clearance of Cryptococcus neoformans capsular polysaccharide in vivo. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8429–8432. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8429-8432.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham S, Huang C, Chen JM, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates intracellular signaling without TNF-alpha release in response to Cryptococcus neoformans polysaccharide capsule. J Immunol. 2001;166:4620–4626. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondo C, Midiri A, Messina L, Tomasello F, Garufi G, Catania MR, Bombaci M, Beninati C, Teti G, Mancuso G. MyD88 and TLR2, but not TLR4, are required for host defense against Cryptococcus neoformans. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:870–878. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Miyagi K, Koguchi Y, Kinjo Y, Uezu K, Kinjo T, Akamine M, Fujita J, Kawamura I, Mitsuyama M, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Takeda K, Akira S, Miyazato A, Kaku M, Kawakami K. Limited contribution of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 to the host response to a fungal infectious pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;47:148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H. The immunobiology of the TLR9 subfamily. Trends in Immunology. 2004;25:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg AM. CpG motifs: the active ingredient in bacterial extracts? Nat Med. 2003;9:831–835. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhan U, Trujillo G, Lyn-Kew K, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Hogaboam CM, Krieg AM, Standiford TJ. Toll-like receptor 9 regulates the lung macrophage phenotype and host immunity in murine pneumonia caused by Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2895–2904. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01489-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhan U, Lukacs NW, Osterholzer JJ, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Moore TA, McMillan TR, Krieg AM, Akira S, Standiford TJ. TLR9 is required for protective innate immunity in Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia: role of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3937–3946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazato A, Nakamura K, Yamamoto N, Mora-Montes HM, Tanaka M, Abe Y, Tanno D, Inden K, Gang X, Ishii K, Takeda K, Akira S, Saijo S, Iwakura Y, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Mitsutake K, Gow NA, Kaku M, Kawakami K. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation of myeloid dendritic cells by deoxynucleic acids from Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3056–3064. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00840-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaks K, Jordan M, Guth A, Sellins K, Kedl R, Izzo A, Bosio C, Dow S. Efficient immunization and cross-priming by vaccine adjuvants containing TLR3 or TLR9 agonists complexed to cationic liposomes. J Immunol. 2006;176:7335–7345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Miyazato A, Xiao G, Hatta M, Inden K, Aoyagi T, Shiratori K, Takeda K, Akira S, Saijo S, Iwakura Y, Adachi Y, Ohno N, Suzuki K, Fujita J, Kaku M, Kawakami K. Deoxynucleic acids from Cryptococcus neoformans activate myeloid dendritic cells via a TLR9-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:4067–4074. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan JM, Wang JP, Lee CK, Levitz SM. Cooperative stimulation of dendritic cells by Cryptococcus neoformans mannoproteins and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, Williams AE, Krieg AM, Rae AJ, Snelgrove RJ, Hussell T. Stimulation via Toll-like receptor 9 reduces Cryptococcus neoformans-induced pulmonary inflammation in an IL-12-dependent manner. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:273–281. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski MA, Huffnagle GB, Traynor TR, McDonald RA, Cook DN, Toews GB. Regulatory effects of macrophage inflammatory protein 1alpha/CCL3 on the development of immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans depend on expression of early inflammatory cytokines. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6256–6263. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6256-6263.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffnagle GB, Boyd MB, Street NE, Lipscomb MF. IL-5 is required for eosinophil recruitment, crystal deposition, and mononuclear cell recruitment during a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection in genetically susceptible mice (C57BL/6). J Immunol. 1998;160:2393–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb MF, Huffnagle GB, Lovchik JA, Lyons CR, Pollard AM, Yates JL. The role of T lymphocytes in pulmonary microbial defense mechanisms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1993;117:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiffoleau E, Heslan JM, Heslan M, Louvet C, Condamine T, Cuturi MC. TLR9 ligand enhances proliferation of rat CD4+ T cell and modulates suppressive activity mediated by CD4+ CD25+ T cell. Int Immunol. 2007;19:193–201. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Lederman MM, Harding CV, Rodriguez B, Mohner RJ, Sieg SF. TLR9 stimulation drives naive B cells to proliferate and to attain enhanced antigen presenting function. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2205–2213. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM, Simpson LJ, Tarleton RL. Insufficient TLR activation contributes to the slow development of CD8+ T cell responses in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:1245–1252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Schaller M, Hogaboam CM, Standiford TJ, Sandor M, Lukacs NW, Chensue SW, Kunkel SL. TLR9 regulates the mycobacteria-elicited pulmonary granulomatous immune response in mice through DC-derived Notch ligand delta-like 4. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:33–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI35647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring AC, Falkowski NR, Chen GH, McDonald RA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Transient neutralization of tumor necrosis factor alpha can produce a chronic fungal infection in an immunocompetent host: potential role of immature dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:39–49. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.39-49.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratchev A, Kzhyshkowska J, Utikal J, Goerdt S. Interleukin-4 and dexamethasone counterregulate extracellular matrix remodelling and phagocytosis in type-2 macrophages. Scand J Immunol. 2005;61:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2005.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katakura T, Miyazaki M, Kobayashi M, Herndon DN, Suzuki F. CCL17 and IL-10 as effectors that enable alternatively activated macrophages to inhibit the generation of classically activated macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;172:1407–1413. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzel W, Muller U, Kohler G, Heppner FL, Blessing M, McKenzie AN, Brombacher F, Alber G. IL-4/IL-13-dependent alternative activation of macrophages but not microglial cells is associated with uncontrolled cerebral cryptococcosis. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:486–496. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Koguchi Y, Qureshi MH, Yara S, Kinjo Y, Miyazato A, Nishizawa A, Nariuchi H, Saito A. Circulating soluble CD4 directly prevents host resistance and delayed-type hypersensitivity response to Cryptococcus neoformans in mice. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:1033–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Ito M, Sano K, Koyama M. Granulomatous and cytokine responses to pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans in two strains of rats. Mycopathologia. 2001;151:121–130. doi: 10.1023/a:1017900604050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholzer JJ, Curtis JL, Polak T, Ames T, Chen GH, McDonald R, Huffnagle GB, Toews GB. CCR2 mediates conventional dendritic cell recruitment and the formation of bronchovascular mononuclear cell infiltrates in the lungs of mice infected with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2008;181:610–620. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Schaller M, Hogaboam CM, Standiford TJ, Chensue SW, Kunkel SL. TLR9 activation is a key event for the maintenance of a mycobacterial antigen-elicited pulmonary granulomatous response. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2847–2855. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffnagle GB, Yates JL, Lipscomb MF. T cell-mediated immunity in the lung: a Cryptococcus neoformans pulmonary infection model using SCID and athymic nude mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1423–1433. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1423-1433.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Mathai D. Clinical manifestations and management of cryptococcal infection. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51 Suppl 1:S21–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sionov E, Chang YC, Garraffo HM, Kwon-Chung KJ. Heteroresistance to fluconazole in Cryptococcus neoformans is intrinsic and associated with virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2804–2815. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00295-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha DC, Goldman DL, Shao X, Casadevall A, Husain S, Limaye AP, Lyon M, Somani J, Pursell K, Pruett TL, Singh N. Serologic evidence for reactivation of cryptococcosis in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1550–1554. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00242-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmesser M, Tucker S, Casadevall A. Intracellular parasitism of macrophages by Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelz K, Lammas DA, May RC. Cytokine signaling regulates the outcome of intracellular macrophage parasitism by Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3450–3457. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00297-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]