Abstract

The syndrome of anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) dependence, though well recognized, remains poorly studied. In this preliminary psychometric study, American and British investigators separately administered a structured diagnostic interview module, based on recently proposed criteria for AAS dependence, to 42 male AAS users in Middlesbrough, England. Another investigator, blinded to the diagnostic interview findings, assessed self-reported symptoms of “muscle-dysmorphia”; effects of AAS on various aspects of functioning; and maximum proportion of annual income spent on AAS. We also assessed demographic measures, history of other substance use, and performance on a hypothetical AAS-purchasing task. The interview module yielded very good interrater reliability (kappa = 0.76 and overall intraclass correlation = 0.79) and strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77–0.87). Men diagnosed as AAS-dependent, when compared to nondependent men, reported significantly earlier onset of AAS use, longer duration and higher maximum doses of AAS used, more frequent use of other performance-enhancing drugs, and a somewhat larger maximum percentage of income spent on AAS. Dependent users also “bought” more AAS in the hypothetical purchase task, but rated significantly more negatively the effects of AAS on their mental health—findings all suggesting that the diagnosis of AAS dependence shows construct validity. As a group, AAS users showed high preoccupation with muscular appearance, but dependence per se was not significantly associated with this measure—suggesting that the diagnosis of AAS dependence shows some evidence of discriminant validity. Collectively, these findings suggest that AAS dependence may be diagnosed reliably, with preliminary evidence for construct and discriminant validity.

Keywords: Anabolic-androgenic steroids, substance dependence, diagnostic interview, psychometrics, behavioral economics

The anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) are a family of drugs comprising testosterone and its numerous synthetic analogs. AAS are widely used by men (and more rarely, women) to gain muscle and lose body fat (H. G. Pope & Brower, 2009). In the United States alone, at least two million individuals have likely used illicit AAS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2008; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009; Kanayama, Hudson, & Pope, in press; McCabe, Brower, West, Nelson, & Wechsler, 2007), and epidemiologic data suggest that there are millions of other AAS users worldwide, particularly in British Commonwealth countries (Baker, Graham, & Davies, 2006; Handelsman & Gupta, 1997; Melia, Pipe, & Greenberg, 1996), Scandinavia (Nilsson, Baigi, Marklund, & Fridlund, 2001; Pallesen, Josendal, Johnsen, Larsen, & Molde, 2006), other parts of Europe (Kokkevi, Fotiou, Chileva, Nociar, & Miller, 2008; Rachon, Pokrywka, & Suchecka-Rachon, 2006; Wanjek, Rosendahl, Strauss, & Gabriel, 2007), and Brazil (J. C. Galduróz, Noto, Nappo, & Carlini, 2005; J. C. F. Galduróz, Noto, Fonseca, & Carlini, 2004). Thus, AAS use represents a major worldwide form of substance abuse.

Many AAS users ingest only a few courses of these drugs in a lifetime, but some go on to develop a syndrome of AAS dependence, where they may use these drugs almost continuously for years, often despite adverse effects (Kanayama, Brower, Wood, Hudson, & Pope, 2009a). We are aware of eight studies over the last 20 years, conducted in the United States (Brower, Blow, Young, & Hill, 1991; Gridley & Hanrahan, 1994; Kanayama, Hudson, & Pope, 2009c; Malone, Dimeff, Lombardo, & Sample, 1995; Perry, Lund, Deninger, Kutscher, & Schneider, 2005; H. G. Pope, Jr. & Katz, 1994), the United Kingdom (Midgley, Heather, & Davies, 1999), and Australia (Copeland, Peters, & Dillon, 2000), that have applied the criteria of DSM-III (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) or modifications of the latter (Kanayama, Brower, Wood, Hudson, & Pope, 2009b) to judge the prevalence of dependence among populations of AAS users in the field. Collectively, these studies have assessed 653 AAS users (641 men, 12 women), of whom 197 (194 men, 3 women; 30.1% of the overall group) were diagnosed with AAS dependence (Kanayama et al., 2009a). Extrapolating from these figures, it would follow that there are likely millions of individuals with AAS dependence worldwide. We have recently reviewed in detail the features of AAS dependence (Kanayama et al., 2009a), noting that it shares many features with classical substance dependence (e.g., animals will self-administer AAS, humans experience a characteristic withdrawal syndrome upon stopping AAS, and AAS use is surrounded by a distinct drug culture in a manner analogous to classical drugs of abuse). On the other hand, AAS dependence differs from classical drug dependence in other ways (e.g., AAS are not acutely intoxicating and hence do not deliver an immediate “reward” upon ingestion, and AAS do not usually compromise daily function in the manner of many intoxicating drugs). We refer the reader to our recent review for a detailed discussion of these similarities and differences. We have also recently reviewed in detail the consequences of long-term AAS use, including particularly the risks of cardiomyopathy, possible atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, medical and psychiatric effects of hypogonadism from suppression of the hypogonadal hypopituitary-testicular axis, occasional effects on liver and kidney function, and other possible long-term psychiatric effects (Kanayama, Hudson, & Pope, 2008). Again we refer the reader to this review for a detailed discussion of these issues.

Despite its prevalence, AAS dependence arguably remains the least studied of all major forms of substance dependence. One problem in studying AAS dependence has been that the standard DSM-IV substance-dependence criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) are difficult to apply to AAS, since these criteria were designed largely to apply to intoxicating drugs (although there are certainly exceptions, such as nicotine). AAS, by contrast, produce little or no acute intoxication. In an attempt to address this problem, a group of investigators (including three of the present authors) has recently published a proposed set of diagnostic criteria for AAS dependence, based on the standard substance-dependence criteria of DSM-IV, slightly modified and adapted to apply specifically to AAS dependence (Kanayama et al., 2009b). Although the DSM-IV substance-dependence criteria as a whole (Budney, 2006; Hasin, Hatzenbuehler, Keyes, & Ogburn, 2006; Helzer, Bucholz, & Gossop, 2007), and structured interviews based upon these criteria (Kranzler, Kadden, Babor, Tennen, & Rounsaville, 1996; Kranzler et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1992) show evidence of reliability and validity, the psychometric properties of the diagnosis of AAS dependence remain to be tested. Accordingly, we performed a preliminary study for which we drafted a brief AAS Interview Module keyed to the proposed AAS dependence criteria, using the same format as the modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2001). We then assessed the inter-rater reliability of this interview module in a sample of 42 male AAS users, and simultaneously obtained several additional measures addressing the construct and discriminant validity of the interview diagnosis of AAS dependence.

Method

Participants

Men aged 18 and over who reported AAS use at some time during their lives were recruited for the study by advertising in local gymnasia in Middlesbrough, England (including a university gym and several other more “hard-core” gyms in the city). The advertisement stated “men 18–65: have you ever used anabolic steroids now or in the past? If so, you can earn £40 by participating in a one-hour research study.” No other inclusion or exclusion criteria were imposed, thus generating a broad sample of AAS users ranging from light or infrequent users to heavy and chronic users. It should be noted that our advertisement was also posted at Lifeline Middlesbrough, a needle-exchange and drug-advice clinic that provided office space for the study. The Lifeline advertisement generated only a small minority of the participants (fewer than 5) – but it should be recognized that this technique might have created some bias in favor of individuals using other types of drugs besides AAS. All participants signed informed consent for the study, which assured participants of confidentiality, and which was approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board (Belmont, Massachusetts, USA).

AAS Interview Module

On the basis of our past experience with conducting structured interviews of AAS users in the field (Kanayama et al., 2009c; Kanayama, Pope, Cohane, & Hudson, 2003; H. G. Pope, Jr. & Katz, 1994), together with findings from other published interview studies involving individuals with AAS dependence (Copeland, Peters, & Dillon, 1998; Malone et al., 1995; Midgley et al., 1999), we created an AAS Interview Module in the format of the SCID. In this format, each of the seven diagnostic criteria for AAS dependence is listed in the central column of the interview, and a probe question, keyed to the criterion, appears in the left-hand column. The interview also contains suggested follow-up questions based on the answer to the probe question, but as with the original SCID, these questions are not restrictive, and interviewers are permitted to expand upon the questions as desired in order to score the criterion accurately. Thus, like the original SCID, the interview is designed for use by an experienced clinician, as opposed to being a rote instrument. In the right-hand column of the instrument, the interviewer scores the answer to the question as 1 = absent, 2 = subthreshold, or 3 = present.

The American and British investigators in the study mutually discussed and refined the draft interview module as much as possible before administering it to the participants. As the study progressed, each participant’s case was reviewed after the interviews had been completed and reasons for disagreement between the two diagnostic interviewers were discussed. On the basis of this experience, we slightly refined the language of several of the interview questions to clarify their interpretation. The final interview module, incorporating these refinements, is presented in an online supplement to this paper.

Procedures

After signing informed consent, participants received duplicate interviews to assess lifetime diagnosis of AAS dependence, using the module described above, by an American diagnostic interviewer (Dr. Pope) and by a British diagnostic interviewer (Mr. Kean). The sequence of the interviews was counterbalanced to prevent order effects, such that half of the participants saw each interviewer first. In addition, the two American investigators at the site (Drs. Pope and Kanayama) assessed basic demographic information and obtained a history of specific AAS used, dosages taken, age at onset of use, duration of use, and details of most recent use. Following the diagnostic interview, these two investigators also elicited history of use of other performance-enhancing drugs and administered a hypothetical AAS purchasing task (described below).

Participants were also administered several additional instruments by a separate British investigator (Mr. Nash), blinded to the diagnostic interview findings. The first of these was the “muscle dysmorphia” version of the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Modification of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (BDD-YBOCS) (Phillips et al., 1997). The BDD-YBOCS is an instrument of demonstrated reliability and validity in the assessment of body dysmorphic disorder (Phillips et al., 1997), which was derived from the original Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Goodman et al., 1989a; Goodman et al., 1989b). We modified the BDD-YBOCS to apply specifically to concerns about body muscularity and physique as opposed to body dysmorphic disorder in general. The instrument is a clinician-administered 12-item scale that generates a score from 0 to 48. A score of zero indicates that the individual devotes little thought to whether or not he appears muscular, and devotes little time to activities associated with appearing muscular (i.e., lifting weights, obtaining special nutrition, wearing clothes that emphasize muscular appearance, assessing muscularity in the mirror, comparing muscularity with others, etc.). We have previously administered this instrument (available from the authors on request) to some 250 experienced weightlifters in an ongoing study in the United States (Kanayama et al., 2009c). In our experience, a total score of 10 on the instrument indicates a considerable preoccupation with muscularity and a score > 20 indicates a severe preoccupation with muscularity. In the present study, we chose to administer the BDD-YBOCS to obtain some information on the discriminant validity of the diagnosis of AAS dependence, in the sense that this diagnosis would not simply indicate heightened concerns about muscularity, but instead would measure a separate construct. Thus, we predicted that scores on the BDD-YBOCS would likely be elevated among AAS users as a whole, but would not be associated with AAS dependence in particular.

The same investigator also asked participants to self-rate the effects of AAS use on various aspects of their functioning on a five-point scale from 1 = strongly positive, 2 = moderately positive, 3 = neutral, 4 = moderately negative, to 5 = strongly negative. The ratings included physical health, mental health, social life, occupational functioning, relationships with women (restricted to heterosexual participants), sexual performance, anxiety level, and mood. This investigator also assessed the maximum percentage of annual income that the participant had spent in any calendar year to purchase AAS. In addition, the investigator performed a brief clinical interview to assess lifetime history of alcohol or classical drug dependence.

Finally, all participants starting with #11 performed a “hypothetical purchase task” in which they were asked how many 10 ml bottles of their preferred AAS (e.g. testosterone cypionate, nandrolone decanoate, etc.) they would buy at any of various hypothetical prices. This task, and others like it, is a product of behavioral economics – an evolving field that seeks to assess the value of drugs and other reinforcers in a quantitatively sophisticated way, as detailed in recent reviews (Bickel, Marsch, & Carroll, 2000; Jacobs & Bickel, 1999) With users of classical substances, such as heroin or cigarettes (Bickel et al., 2000; Jacobs & Bickel, 1999), the hypothetical purchase task normally asks how much of the drug an individual would purchase for personal use in a single day. However, AAS are usually taken in courses of 6–12 weeks in length, making the standard administration of the task inappropriate. Therefore, we modified the task to how much AAS the individual would purchase to stock up for long-term personal use (i.e., the individual could purchase unlimited hypothetical AAS for personal use, but was not allowed to purchase hypothetical AAS to be given or sold to others). The task begins by asking how many bottles the individual would purchase at £1 per bottle, with the same question repeated for hypothetical bottle prices of £2, £3, £5, £8, £13, £21, £34, £55, £89, £144, £233, £377, £610, and £987.

Data analysis

To determine the agreement between the two interviewers’ administrations of the AAS Interview Module, we computed both categorical and dimensional indicators of interrater reliability. We use the term “interrater reliability” here to describe this agreement; it is also often called “test-retest reliability” (Hasin et al., 2006). The overall diagnostic agreement for the categorical diagnosis of AAS dependence was calculated using the kappa statistic. For this purpose, scores of 2 (subthreshold) were recoded as 1 (non-dependent). We also counted the number of criteria rated as present by each interviewer (i.e., 0–7) and calculated intraclass correlations (ICCs) between these values to provide a dimensional measure of agreement. Finally, ICCs were also used to indicate the agreement for the ratings of each individual diagnostic criterion. Internal consistency of the interview measure was assessed separately for each interviewer using Cronbach’s alpha. However, since Cronbach’s alpha is sensitive to scale length, we also calculated averaged corrected item-total correlations using the dimensional ratings for each criterion.

To obtain preliminary indications about the potential validity of the diagnosis AAS dependence, we compared the 15 unequivocally non-dependent men (scored as “1” by both interviewers) with the 19 unequivocally dependent men (scored as “3” by both interviewers), while excluding the 8 men who were equivocal in any way (i.e., cases where the interviewers disagreed or where either or both interviewers scored a “2”). The outcome variables for these comparisons included demographic data, measures of use of AAS and other drugs, and ratings performed by the blinded British interviewer as described above. For these comparisons, we used linear regression for continuous outcome variables, with adjustment for participants’ age. Self-ratings of the effects of AAS on functioning were modeled as binary variables (negative effects versus neutral or positive effects). Differences between groups were assessed by logistic regression with adjustment for age, except when the expected cell size was < 5, in which case Fisher’s exact test was used. For the hypothetical purchase task, we compared groups by linear regression using ranked data, an established method in cases where data are not normally distributed (Conover & Iman, 1982), with adjustment for age. However, we did not adjust these comparisons for participants’ current income, because we did not possess these data. Nevertheless, we did exclude one outlier -- an affluent nondependent user who claimed that he would spend more than £12000 for hypothetical AAS, a figure 12 times as great as any other participant. Outcome measures on the hypothetical purchase task included intensity (number of bottles purchased at the lowest price), Omax (maximum expenditure for AAS at any price), Pmax (price at which demand becomes elastic; i.e., the price after which the number of bottles purchased began to decrease) and breakpoint (the highest price at which the participant would purchase any hypothetical AAS). However, we did not calculate more complex outcome measures such as elasticity (Bickel et al., 2000; Hursh & Silberberg, 2008), given the small sample sizes (N = 11 and 12 participants, respectively) and the unconventional method of administration (a long-term supply of drug as opposed to a one-day supply). In all tests of significance, we set alpha at 0.05, two-tailed. Note that the significance of differences is not corrected for multiple comparisons, since many of the comparisons were correlated, making a Bonferroni correction potentially too conservative. Although there are reasons for favoring the presentation of significance levels without correction (Feise, 2002; Savitz & Olshan, 1995), the greater possibility of chance associations must nevertheless be considered when evaluating the tests of significance that we have reported.

Results

We evaluated 42 men reporting AAS use, who spanned a range of ages (mean age = 28.1 years; SD = 6.8 years; range 18–43 years) and socioeconomic status (mean annual income at time of maximum AAS use, £17,100; SD = £11,900; range £4160 - £50,000). Thirty-seven (88%) of the men were Caucasian, one (2%) was Black, and 4 (10%) were Asian. Ten (24%) were students; 19 (45%) were currently employed and 13 (31%) were currently unemployed. Thirty-six (83%) were currently lifting weights regularly at a gymnasium, whereas 6 (17%) had lifted weights only in the past. Sixteen (38%) were currently using AAS at the time of the evaluation, and three others (7%) had completed a recent course of AAS within the past one month.

Interrater reliability

Results from the diagnostic interviews (Table 1) showed that the American and British interviewers reached identical diagnoses of AAS dependence for 35 (86%) of the cases, one of which represented a consensus diagnosis of subthreshold AAS dependence (i.e., a score of “2” on the interview module). In 3 (7%) of the cases there was partial disagreement, with one interviewer assigning a subthreshold diagnosis and the other a full-scale diagnosis of dependence or nondependence. In the remaining 3 cases there was complete disagreement, with one interviewer diagnosing full-scale dependence and the other nondependence. Grouping subthreshold cases with nondependent cases as described above, these results yielded a kappa coefficient of .76, indicating very good agreement. Additionally, within the group of 19 individuals scored by both interviewers as AAS dependent, we obtained complete agreement on current versus past use, with both interviewers scoring 11 (58%) of the men as currently dependent and the other 8 (42%) as past dependent only.

Table 1.

Interview diagnoses of AAS dependence among 42 AAS users

| British interviewer (JK) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | No AAS dependence | Subthreshold dependence | AAS dependence | Total | |

| No AAS dependence | 15 | 2 | 2 | 19 | |

| American interviewer (HGP) | Subthreshold dependence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| AAS dependence | 1 | 0 | 19 | 20 | |

| Total | 16 | 3 | 23 | 42 | |

Interrater reliability was also considered dimensionally, via the count of criteria rated as present by each interviewer. These scores, ranging from 0 to 7 for each interviewer, were compared using intraclass correlation (ICC). Interrater reliability by this metric was also very good, with a value of .79. Finally, we also investigated the agreement for each of the individual diagnostic criteria ratings (i.e., 1, 2, or 3) assigned by each interviewer. The ICCs for the seven criteria ranged from a low of .48 for criterion 6 (i.e., “other important activities reduced because of substance use”) to a high of .88 for criterion 3 (i.e., “substance often taken in larger doses or for longer than intended”) with a median value of .65 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Individual Interview Items

| Criterion | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|

| 1. Tolerance | 0.65 |

| 2. Withdrawal | 0.75 |

| 3. AAS used in larger amounts or longer than intended | 0.88 |

| 4. Desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use | 0.78 |

| 5. Great deal of time associated with obtaining and using AAS | 0.59 |

| 6. Other activities given up or reduced because of AAS use | 0.48 |

| 7. Continued AAS use despite adverse effects | 0.64 |

| Median for all individual interview items | 0.65 |

Internal consistency

Because the interview was administered twice, we calculated internal consistency separately for each interviewer. Cronbach’s alpha values for interviewers 1 (HGP) and 2 (JK) were .87 and .77, respectively. To provide a more conservative test of internal consistency, we calculated average corrected item-total correlations, which assess the correlation between each individual criterion and the overall sum of all other criteria. This provides a value for each criterion indicating how strongly it relates to the others. These values were then averaged to provide overall estimates of internal consistency for the scale as a whole. The averaged corrected item total correlations for the two interviewers were .65 and .50, respectively.

Construct validity

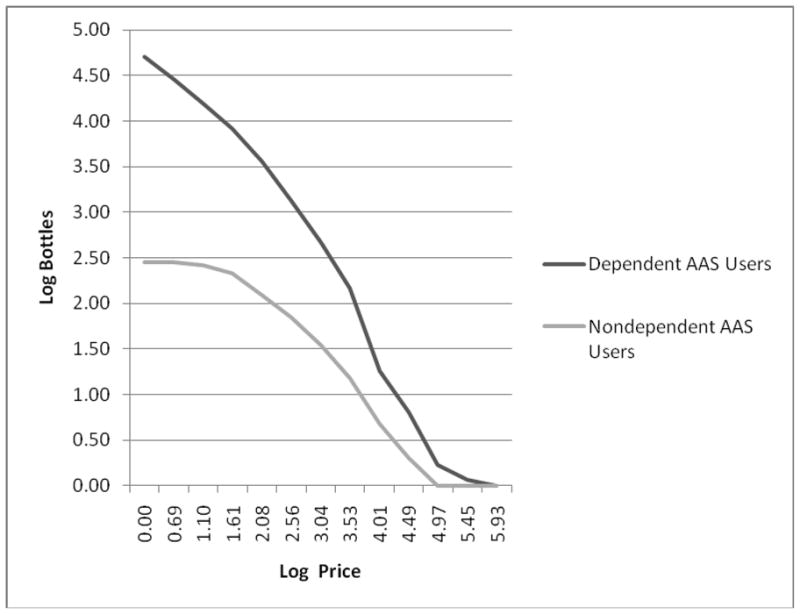

Because neither interviewer was considered primary, we focused our subsequent analyses on the 19 unequivocally dependent cases and the 15 unequivocally non-dependent cases, as defined above, using a variety of outcome measures that might be expected to provide evidence of construct validity for the diagnosis of AAS dependence. Dependent users were older than non-dependent AAS users, but both groups began lifting weights at approximately the same age (Table 3). The AAS-dependent group first used AAS at a significantly younger age, had used AAS significantly longer (even when adjusting for their greater current age), and had ingested significantly higher maximum weekly doses. There was a trend for dependent users to have spent a larger percentage of their annual income to purchase AAS during the calendar year of maximum use, although this difference fell slightly short of statistical significance (p = 0.06). Dependent users were significantly more likely to have ingested other performance-enhancing drugs at some time in their lives. AAS-dependent men more often reported a lifetime history of dependence on classical drugs of abuse or alcohol, but this difference did not approach significance (p = 0.36). On the hypothetical purchase task, dependent users displayed significantly greater intensity (number of bottles purchased at the lowest price) and Omax (maximum expenditure) than non-dependent users, although the Pmax values and breakpoints did not differ significantly (Table 4). Demand curves for the two groups (Figure 1) illustrate the markedly greater hypothetical consumption among dependent users. Parenthetically, even with the inclusion of the nondependent outlier mentioned above, the groups remained significantly different on intensity (p = 0.03) and almost significantly different on Omax (p = 0.06).

Table 3.

Weightlifting and Substance Use in Dependent vs. Non-dependent AAS users

| Group | Between-group Comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent AAS users (N = 19) | Nondependent AAS users (N = 15) | Mean Difference (95% confidence interval)d | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Current age | 31.5 | 6.1 | 24.9 | 7 | p = 0.007e |

| Age began regular weightlifting | 18.2 | 4.8 | 18.6 | 6.8 | −2.8 (−7.0, 1.4) |

| Age at onset of AAS use | 21.5 | 4.3 | 22.3 | 6.8 | −4.4 (−7.8, −1.0)* |

| Lifetime weeks of AAS use | 202.7 | 140.7 | 17.3 | 22 | 149.0 (68.6, 229.5)*** |

| Maximum weekly dose of AAS used, milligramsa | 1560 | 800 | 598 | 385 | 823 (311, 1335)** |

| Maximum percent of annual income spent on AAS | 4.4 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 (−0.2, 4.9) |

| N | % | N | % | Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval)f | |

| Lifetime use of other performance-enhancing drugsb | 12 | 63 | 2 | 13 | 8.9 (1.4, 67.7)* |

| History of classical substance dependencec | 7 | 37 | 2 | 13 | 2.4 (0.4, 16.0) |

Calculated as milligrams of testosterone equivalent as previously described (Pope & Katz, 1994).

Dependent users: human growth hormone = 6; growth-hormone releasing factor-6 = 1; clenbuterol = 6; insulin = 3; thyroid hormones = 3; ephedrine > 1 month = 6; human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) = 3 (note that many men reported > 1 drug.)

Non-dependent users: human growth hormone = 1; clenbuterol = 1.

Dependent users: opioid dependence = 2; cannabis= 3; stimulants = 1; alcohol = 2.

Non-dependent users: opioids = 1; cannabis = 1; sedatives/hypnotics = 1.

By linear regression with adjustment for age (except for initial comparison of current age); * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

By t test, two-tailed.

By logistic regression with adjustment for age; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Hypothetical Purchase Task Performance in Dependent vs. Non-dependent AAS users

| Group | Between-group Comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurea | Dependent AAS users (N = 11) | Nondependent AAS users (N = 12) b | P valuec | ||

| Median | Interquartile range | Median | Interquartile range | ||

| Intensity | 100 | 12, 500 | 10 | 4, 23 | 0.03 |

| Omax | 525 | 275, 1040 | 150.5 | 82.25, 208.5 | 0.01 |

| Pmax | 2 | 1, 21 | 6.5 | 3.5, 30.75 | 0.24 |

| Breakpoint | 89 | 34, 89 | 55 | 34, 89 | 0.23 |

Measures: Intensity = Number of hypothetical bottles of AAS purchased at lowest price (£1 per bottle); Omax = Maximum expenditure for AAS (in £); Pmax = Price at which demand becomes elastic (in £); Breakpoint = Highest price at which the participant would buy any bottles of AAS (in £).

Excludes one outlier; see text.

By linear regression using ranked data with adjustment for age (see text).

Figure 1.

Demand curves showing the supply of hypothetical bottles of AAS purchased for long-term personal use by dependent versus nondependent AAS users on the Hypothetical Purchase Task. Both axes are scaled as natural logarithms. Note that one nondependent outlier is omitted (see text).

On the self-report measures, dependent AAS users were generally more likely than nondependent users to report negative or adverse effects (Table 5). This difference was greatest on self-ratings of the effects of AAS on “mental health,” where nearly half of dependent users generated negative ratings, as compared with only a single non-dependent user. Typically these negative ratings reflected either depression experienced during withdrawal after stopping a course of AAS, or serious irritability and aggressiveness while taking AAS, which in some cases had caused participants to lose girlfriends, alienate family members, or even get arrested.

Table 5.

Self-ratings of the Effects of AAS on Aspects of Life Functioning

| Group | Between-group Comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants reporting that AAS had a “moderately” or “strongly” negative effect on their: | Dependent AAS users (N = 19) | Nondependent AAS users (N = 15) | P valuea | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Physical health | 3 | 16 | 1 | 7 | 0.41 |

| Social life | 6 | 32 | 1 | 7 | 0.07 |

| Occupational function | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.37 |

| Relationships with womenb | 7 | 37 | 2 | 13 | 0.12 |

| Sexual performance | 6 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Anxiety levelc | 8 | 42 | 4 | 27 | 0.42 |

| Moodc | 5 | 26 | 3 | 20 | 0.67 |

| Mental health | 9 | 47 | 1 | 7 | 0.01 |

By Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed; comparisons are not adjusted for age because expected cell sizes are < 5 in all cases except “anxiety level”; see text.

All participants reported a heterosexual orientation.

A “negative effect” indicates a self-report that AAS worsened anxiety or mood symptoms.

Discriminant validity

The 42 AAS users as a whole showed high total scores on the muscle dysmorphia version of the BDD-YBOCS (mean [SD] score = 14.4 [8.6]; range 2–41), indicating prominent concerns about body muscularity and physique. However, upon comparing the 19 dependent and 15 nondependent users as classified above, we found no significant difference between groups in total scores (16.6 [9.0] versus 12.9 [8.8]; adjusted mean difference [95% CI] 3.2 [−3.9, 10.4]; p = 0.36), nor on 11 of the 12 individual scale items (p > 0.18 in all cases). Only on one item (“time occupied by thoughts about physique”), did dependent users significantly exceed nondependent users (2.4 [1.0] versus 1.6 [0.8] on the four-point scale; adjusted mean difference [95% CI] 1.0 [0.2, 1.7]; p = 0.01). Thus, the AAS Interview Module and the “muscle dysmorphia” version of the BDD-YBOCS appeared to be measuring separate constructs. These findings accord with preliminary data from an ongoing American study of experienced male weightlifters, suggesting that body image disorder is strongly associated with initiation of AAS use, but is not strongly associated with progression from AAS use to AAS dependence (Kanayama et al., 2009a).

Discussion

Anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) dependence likely represents an evolving worldwide public health problem, but remains little studied, perhaps in part because specific diagnostic criteria for AAS dependence have not been proposed until recently (Kanayama et al., 2009a, 2009b). Indeed, AAS represent one of the few classes of substances scheduled by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (United States Drug Enforcement Administration. 2002) for which DSM-IV does not explicitly recognize a dependence syndrome (other such exceptions include gamma hydroxybutyrate and ketamine). However, the recent publication of proposed diagnostic criteria for AAS dependence offers an opportunity to obtain preliminary psychometric data regarding this diagnostic entity. In the present study, we created a structured interview module for the diagnosis of AAS dependence, using the format of the SCID, and tested the interrater reliability and internal consistency of this instrument, while also obtaining some preliminary measures of construct and discriminant validity, in a sample of 42 male AAS users.

The AAS Interview Module demonstrated good internal consistency, suggesting that the individual criteria assess a relatively homogenous construct. More importantly, American and British diagnostic interviewers obtained high levels of interrater reliability for the categorical diagnosis of lifetime dependence (k = 0.76). This value is quite comparable with those reported in a systematic review of studies of other substance-dependence diagnoses (Hasin et al., 2006). For example, an American community study using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS) obtained kappa values for lifetime dependence of .65 (alcohol), .70 (cannabis), .81 (heroin), and .89 (cocaine) (Grant, Harford, Dawson, Chou, & Pickering, 1995). Interrater agreement in the current study was also quite good when considered dimensionally at the level of the diagnosis. The values were also generally good for the individual diagnostic criteria, but interrater agreement for criterion 6 (“important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use”) was marginal.

Our average corrected item total correlations were modest at 0.65 for the psychiatrist interviewer and 0.50 for the non-psychiatrist interviewer. However, it should be noted that this is a conservative test, not commonly reported in assessments of dependence for other substances. In one of the few comparable studies to report this statistic (Baer, Ginzler, & Peterson, 2003), using the SCID to assess various forms of substance dependence, average corrected item total correlations were .64, .62, .54, and .37 for heroin, amphetamines, alcohol, and marijuana dependence, respectively. The more commonly reported measure of internal consistency is Cronbach’s alpha, and on this statistic the values for the psychiatrist interviewer (0.87) and the non-psychiatrist interviewer (0.77) were both above .70, which has been proposed as a threshold for adequacy (Nunnelly, 1978).

In addition, our comparisons of AAS-dependent and non-dependent men provided tentative support for the construct validity of the diagnosis. For example, AAS-dependent men reported significantly earlier onset of AAS use, longer duration and higher maximum doses of AAS used, and a higher prevalence of use of other performance-enhancing drugs. Dependent AAS users also showed a significantly greater “willingness to buy” AAS in a hypothetical purchase task, as measured by intensity and Omax (albeit not differing on Pmax or breakpoint; see below). Although we are not aware of previous studies explicitly comparing dependent vs. nondependent users of other substances on hypothetical drug-purchase tasks, our findings appear consistent with the notion that dependence should reflect difficulty in controlling one’s use of the substance. In a somewhat similar finding, however, MacKillop and Murphy (2007) showed that high levels of demand for alcohol on a purchase task predicted poor response to a brief alcohol intervention (i.e., greater follow-up drinking). This suggests that purchase tasks may reflect difficulty in modulating substance use. Our findings also somewhat parallel studies using an alcohol purchase task in college students, where students with recent heavy drinking or alcohol-related problems showed significantly greater intensity and Omax than comparison students (Murphy & MacKillop, 2006; Murphy, MacKillop, Skidmore, & Pederson, 2009). We also found a trend for AAS-dependent men to spend a larger maximum portion of their annual income to purchase AAS. This observation somewhat parallels previous behavioral economic data showing that individuals with unstable resolutions of alcohol dependence reported greater proportional expenditures on alcohol than individuals with stable resolutions (Tucker, Vuchinich, Black, & Rippens, 2006; Tucker, Vuchinich, & Rippens, 2002). Importantly, however, AAS-dependent men generated significantly more negative self-report scores on the effects of AAS on their mental health – consistent with the notion that dependence should reflect maladaptive use of a drug. However, this last finding should be interpreted with recognition that the AAS-dependent men exhibited somewhat greater comorbid substance dependence, which might contribute to the observed differences via interactions between AAS and these other drugs, or the presence of general risk factors (such as personality or negative affect) associated with other forms of drug or alcohol dependence. We also found tentative evidence (albeit using only a single measure) that the diagnosis of AAS dependence showed some discriminant validity, in that AAS users as a whole showed high preoccupation with muscular body appearance on the BDD-YBOCS, but dependence per se was not significantly associated with overall BDD-YBOCS scores, nor with any of the 12 individual BDD-YBOCS items, save for “time occupied by thoughts about physique,” as mentioned above. Finally, we would acknowledge that our brief evaluation failed to include other measures that might have proved useful in comparisons between groups (e.g., family history of substance abuse disorders, history of childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders, history of nicotine use, etc.).

In considering these findings, it should be recognized that although this study found very good interrater reliability using recently published specific criteria for AAS dependence and a new interview module based on these criteria, we cannot conclude that these criteria, or the interview module, are necessarily more reliable than the existing generic DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence or to existing diagnostic tools such as the SCID. Further investigation will be required to ascertain whether our criteria and interview module offer an advantage over the existing DSM-IV classification of AAS dependence as “other” dependence (304.90). In addition, given the very preliminary nature of our findings regarding validity, further research will be required to ascertain whether our diagnostic tool successfully distinguishes AAS dependence from simple AAS abuse or misuse.

Another consideration is that an interview for diagnosing AAS dependence, however reliable, may be of little practical value if AAS-dependent individuals rarely desire treatment. We have discussed this issue of treatment-seeking in detail in a recent paper (Kanayama, Brower, Wood, Hudson, & Pope, 2010). In this paper, we note that AAS users have historically been reluctant to seek treatment, but suggest that there will likely be a substantial increase in AAS-dependent men seeking treatment over the next decade, as rapidly increasing numbers of dependent users grow old enough to enter the age of risk for medical and psychiatric consequences of prolonged AAS exposure (Kanayama et al., 2008). It also seems hopeful that treatment-seeking will increase as AAS dependence becomes better recognized and publicized as a disorder, as AAS users become better informed about the potential hazards of long-term AAS use, and as more specific treatment approaches for AAS dependence are developed (Kanayama et al., 2010). In this connection, we would note parenthetically that about half of the dependent users encountered in the present study had sought at least some degree of drug advice or counseling at Lifeline Middlesbrough, whose offices we used for the study.

Several additional limitations of these findings must be considered. First, the men recruited for this study were self-acknowledged AAS users, and hence may have provided more detailed information about the extent and correlates of their AAS use than an unselected sample of community individuals. Thus, interrater reliability obtained in this study might be higher than that obtained in the field. However, if field studies yielded lower rates of reliability, this would largely reflect the failure of AAS users to disclose the full extent of their AAS use or associated morbidity, rather than defects inherent to the proposed diagnostic criteria or to the interview module itself.

A strength of the study is that high reliability was obtained with interviewers from different cultural and educational backgrounds, but a weakness is that the study was based on a modest sample of individuals in a single locality. Thus, these results must be regarded as preliminary pending larger investigations at multiple sites. This same limitation must be considered with regard to the measures of validity. In particular, it is our impression that amounts of AAS purchased (both real and hypothetical), concomitant use of other performance-enhancing drugs, and use of classical drugs may vary across different geographical locations. For example, although it is illegal to buy or sell AAS in the United Kingdom, it is legal to possess a personal supply of these drugs there, whereas even the possession of AAS is illegal in the United States and many Western European countries. Such cross-national differences would not threaten the validity of comparisons between dependent and nondependent users within the present study, since all were evaluated at the same location, but these differences might limit the generalizability of the findings to other locations.

A corollary consideration is that several of our outcome measures, such as the muscle dysmorphia version of the BDD-YBOCS, the AAS self-ratings, or the AAS hypothetical purchase task, have not been formally tested for reliability and validity. Again however, since each of these instruments was administered in an identical manner by a single investigator to all participants, comparisons between dependent and nondependent users within the study would still be valid, even though the findings might not generalize to other interviewers or other settings.

Although our comparisons of the dependent and nondependent groups were adjusted for age, this adjustment does not fully account for the possibility that some of the nondependent users might have been en route to dependence, but were still too young to have achieved dependence when we evaluated them. Favoring this possibility, we would note that the mean (SD) age of onset of dependence in the 19 AAS-dependent men was 24.4 (3.5) years, while 8 (53%) of the 15 non-dependent users were under age 24. However, if our non-dependent group did include some younger “pre-dependent” men, this would likely narrow observed differences between groups, because “pre-dependent” men would likely be closer to the dependent men on the various outcome measures. Thus, if anything, our estimated differences between groups would be conservative.

We should also note that the AAS-dependent men showed significantly greater intensity and Omax values on the hypothetical purchase task than non-dependent users, but they did not show correspondingly greater Pmax values or breakpoints (Table 3). However, the lack of difference on these latter values might be simply a ceiling effect due to the non-standard way in which the task was administered (e.g., purchasing a hypothetical long-term supply of drug rather than the more standard one-day supply). An alternative explanation, suggested by a recent factor analytic study of an alcohol purchase task (Mackillop et al., 2009), is that intensity and Omax may represent a different domain from indices of price sensitivity. Additionally, a recent test-retest reliability study with the same alcohol purchase task (Murphy et al., 2009) found that intensity and Omax were the most reliable parameters, thus offering support for the focus on these indices in the present study.

Another limitation of the study is that blinding was imperfect. Although the two diagnostic interviewers (HGP and JK) remained thoroughly blinded to one another for purposes of the reliability measures, it was not feasible to remain fully blind to AAS dependence status when inquiring about the validity measures (e.g., history of use of other performance-enhancing drugs, hypothetical purchase task, BDD-YBOCS, etc.). In particular, even though the separate British interviewer (AN) was technically blinded to dependence status, he could not avoid seeing that some men exhibited visibly supraphysiologic levels of muscularity suggestive of high-dose AAS use. Parenthetically, we would note that we did not perform formal measurements of muscularity, such as fat-free mass index (Kouri, Pope, Katz, & Oliva, 1995), in the participants, and thus cannot assess whether levels of muscularity were related to specific dependence criteria such as tolerance.

Finally, an inherent limitation of this study, as with most other studies of validity in psychiatry, is that there is no “gold standard” for determining the validity of a given psychiatric diagnosis in a manner analogous to a positive pathological finding in a medical illness. Thus, the psychiatric validation measures are in some cases partially tautological. For example, we found that AAS-dependent individuals, as compared with nondependent individuals, had used AAS for longer periods and at higher doses – but these same factors contributed to the diagnosis of AAS dependence in the first place. However some other measures, such as age at onset of AAS use, use of other performance-enhancing drugs, or self-reports of functional impairment, were less dependent on the initial diagnostic criteria and hence less vulnerable to such potential tautologies.

Overall, despite the above limitations, many of which are inherent to all naturalistic studies of substance users, our findings suggest that the diagnosis of AAS dependence can be made reliably, with levels of interrater agreement and internal consistency comparable to those demonstrated for other forms of substance dependence. Our study also provides some initial evidence that the diagnosis of AAS dependence identifies a valid syndrome. However, these findings must be regarded as preliminary, and should be expanded to include more extensive measures, in larger samples of participants, across other geographic locations. Such further research on AAS dependence is much needed, given that AAS dependence remains probably the least studied of the major worldwide forms of substance dependence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIDA Grant DA 016744 (to Drs. Pope, Kanayama, and Hudson), MIRECC Fellowhip, Department of Veterans Affairs (Dr. Samuel), and NIDA Grant DA 022386 (to Dr. Bickel)

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Ginzler JA, Peterson PL. DSM-IV alcohol and substance abuse and dependence in homeless youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(1):5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JS, Graham MR, Davies B. Steroid and prescription medicine abuse in the health and fitness community: A regional study. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2006;17(7):479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Carroll ME. Deconstructing relative reinforcing efficacy and situating the measures of pharmacological reinforcement with behavioral economics: a theoretical proposal. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2000;153(1):44–56. doi: 10.1007/s002130000589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96(1):73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brower KJ, Blow FC, Young JP, Hill EM. Symptoms and correlates of anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence. British Journal of Addictions. 1991;86(6):759–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb03101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ. Are specific dependence criteria necessary for different substances: how can research on cannabis inform this issue? Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):125–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2007. [accessed September 06, 2009];Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008 57(SS-4) Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/yrbss07_mmwr.pdf. [PubMed]

- Conover WJ, Iman RL. Analysis of covariance using the rank transformation. Biometrics. 1982;38(3):715–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Peters R, Dillon P. A study of 100 anabolic-androgenic steroid users. Medical Journal of Australia. 1998;168(6):311–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Peters R, Dillon P. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use disorders among a sample of Australian competitive and recreational users. Drug And Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60(1):91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feise RJ. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders -- Patient Edition. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Galduróz JC, Noto AR, Nappo SA, Carlini EA. Household survey on drug abuse in Brazil: study involving the 107 major cities of the country--2001. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(3):545–556. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galduróz JCF, Noto AR, Fonseca AM, Carlini EA. São Paulo, Brazil: Centro Brasileiro de Informações sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas; 2004. Levantamento Nacional Sobre o Consumo de Drogas Psicotrópicas entre Estudantes do Ensino Fundamental e Médio da Rede Pública de Ensino nas 27 Capitais Brasileiras-2004. Available online at: http://www.cebrid.epm.br/levantamento_brasil2/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989a;46(11):1012–1016. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110054008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Henniger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989b;46(11):1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou PS, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;39(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley DW, Hanrahan SJ. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use among male gymnasium participants: knowledge and motives. Sports Health. 1994;12:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Handelsman DJ, Gupta L. Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse in Australian high school students. International Journal of Andrology. 1997;20(3):159–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1997.d01-285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes K, Ogburn E. Substance use disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):59–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Bucholz KK, Gossop M. A dimensional option for the diagnosis of substance dependence in DSM-V. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2007;16(Suppl 1):S24–33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychological Review. 2008;115(1):186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Bickel WK. Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7(4):412–426. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. College Students and Adults Ages 19 to 5 0 (NIH Publication No. 09-7402) II. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Brower KJ, Wood RI, Hudson JI, Pope HG. Anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: an emerging disorder. Addiction. 2009a;104:1966–1978. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02734.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Brower KJ, Wood RI, Hudson JI, Pope HG. Treatment of anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: emerging evidence and its implications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.011. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Brower KJ, Wood RI, Hudson JI, Pope HG., Jr Issues for DSM-V: clarifying the diagnostic criteria for anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009b;166(6):642–645. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Hudson JI, Pope HG. Illicit anabolic-androgenic steroid use. Hormones and Behavior. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.09.006. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Hudson JI, Pope HG., Jr Long-term psychiatric and medical consequences of anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse: a looming public health concern? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98(1–2):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Hudson JI, Pope HG., Jr Features of men with anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence: A comparison with nondependent AAS users and with AAS nonusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009c;102(1–3):130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama G, Pope HG, Cohane G, Hudson JI. Risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid use among weightlifters: a case-control study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkevi A, Fotiou A, Chileva A, Nociar A, Miller P. Daily exercise and anabolic steroids use in adolescents: a cross-national European study. Substance Use and Misuse. 2008;43(14):2053–2065. doi: 10.1080/10826080802279342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL, Oliva P. Fat-free mass index in users and nonusers of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 1995;5(4):223–228. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, Tennen H, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of the SCID in substance abuse patients. Addiction. 1996;91(6):859–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Burleson JA, Babor TF, Apter A, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of psychiatric diagnoses in patients with substance use disorders: is the interview more important than the interviewer? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1995;36(4):278–288. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Murphy JG. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;89(2–3):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Bickel WK. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone DA, Jr, Dimeff RJ, Lombardo JA, Sample RH. Psychiatric effects and psychoactive substance use in anabolic-androgenic steroid users. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 1995;5(1):25–31. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Brower KJ, West BT, Nelson TF, Wechsler H. Trends in non-medical use of anabolic steroids by U.S. college students: results from four national surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90(2–3):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melia P, Pipe A, Greenberg L. The use of anabolic-androgenic steroids by Canadian students. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;6(1):9–14. doi: 10.1097/00042752-199601000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley SJ, Heather N, Davies JB. Dependence-producing potential of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Addiction Research. 1999;7:539–550. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14(2):219–227. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17(6):396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson S, Baigi A, Marklund B, Fridlund B. The prevalence of the use of androgenic anabolic steroids by adolescents in a county of Sweden. European Journal of Public Health. 2001;11(2):195–197. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnelly JC. Psychometric Theory. 2. San Francisco: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S, Josendal O, Johnsen BH, Larsen S, Molde H. Anabolic steroid use in high school students. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41(13):1705–1717. doi: 10.1080/10826080601006367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry PJ, Lund BC, Deninger MJ, Kutscher EC, Schneider J. Anabolic steroid use in weightlifters and bodybuilders: an internet survey of drug utilization. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;15(5):326–330. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000180872.22426.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Hollander E, Rasmussen SA, Aronowitz BR, DeCaria C, Goodman WK. A severity rating scale for body dysmorphic disorder: development, reliability, and validity of a modified version of the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Psychopharmacological Bulletin. 1997;33(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Brower KJ. Anabolic-Androgenic Steroid-Related Disorders. In: Sadock B, Sadock V, editors. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. pp. 1419–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Katz DL. Psychiatric and medical effects of anabolic-androgenic steroid use. A controlled study of 160 athletes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51(5):375–382. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachon D, Pokrywka L, Suchecka-Rachon K. Prevalence and risk factors of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) abuse among adolescents and young adults in Poland. Sozial- und Praventivmedizin. 2006;51(6):392–398. doi: 10.1007/s00038-006-6018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz DA, Olshan AF. Multiple comparisons and related issues in the interpretation of epidemiologic data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142(9):904–908. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Black BC, Rippens PD. Significance of a behavioral economic index of reward value in predicting drinking problem resolution. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(2):317–326. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Rippens PD. Predicting natural resolution of alcohol-related problems: a prospective behavioral economic analysis. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10(3):248–257. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Code Title 21; Controlled Substances Act; Section 812, Schedules of Controlled Substances. [accessed September 6, 2009];2002 Available online at http://www.usdoj.gov/dea/pubs/csa/812.htm.

- Wanjek B, Rosendahl J, Strauss B, Gabriel HH. Doping, drugs and drug abuse among adolescents in the State of Thuringia (Germany): prevalence, knowledge and attitudes. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007;28(4):346–353. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.