Abstract

We examined the efficacy of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) and compared outcomes of 93 patients older than 16 years after RIC with 1428 patients receiving full-intensity conditioning for allografts using sibling and unrelated donors for Philadelphia-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in first or second complete remission. RIC conditioning included busulfan 9 mg/kg or less (27), melphalan 150 mg/m2 or less (23), low-dose total body irradiation (TBI; 36), and others (7). The RIC group was older (median 45 vs 28 years, P < .001) and more received peripheral blood grafts (73% vs 43%, P < .001) but had similar other prognostic factors. The RIC versus full-intensity conditioning groups had slightly, but not significantly, less acute grade II-IV graft-versus-host disease (39% vs 46%) and chronic graft-versus-host disease (34% vs 42%), yet similar transplantation-related mortality. RIC led to slightly more relapse (35% vs 26%, P = .08) yet similar age-adjusted survival (38% vs 43%, P = .39). Multivariate analysis showed that conditioning intensity did not affect transplantation-related mortality (P = .92) or relapse risk (P = .14). Multivariate analysis demonstrated significantly improved overall survival with: Karnofsky performance status more than 80, first complete remission, lower white blood count, well-matched unrelated or sibling donors, transplantation since 2001, age younger than 30 years, and conditioning with TBI, but no independent impact of conditioning intensity. RIC merits further investigation in prospective trials of adult ALL.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has an established role in the management of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in first or second complete remission (CR1 and CR2). Recent large prospective donor versus no donor analyses showed that matched sibling allografting yields superior outcomes compared with chemotherapy,1 and its use is recommended in the highest-risk, Philadelphia chromosome–positive (Ph+) cohort.1 A recent report described encouraging results with allografting from unrelated donors (URDs) for patients with Ph-negative (Ph−) ALL in CR1 at high risk of relapse.2 Although only a minority of adult patients achieve a second remission and remain fit for a transplantation,3 allogeneic HSCT is still the treatment of choice for adults with ALL in CR2 where sibling donor allografts yield disease-free survival (DFS) of 25% to 40%.4 Most conditioning regimens involve the use of total body irradiation (TBI) with some evidence favoring doses exceeding 13 Gy.5,6 Reports of non–TBI-containing regimens for ALL are limited.

Allogeneic HSCT may be the most effective antileukemic therapy in adult ALL, but results are compromised by high transplantation-related mortality (TRM), approaching 35% in patients older than 35 years.1 In an attempt to avoid the high TRM seen with full-intensity (FI) HSCT and to exploit the graft-versus- ALL effect, investigators have been exploring the role of reduced- intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens. Results have been difficult to evaluate because of regimen heterogeneity and small numbers.

Various conditioning regimens have been used, including very low-intensity (eg, fludarabine and TBI 2 Gy) or more intense regimens, such as fludarabine and melphalan.7 Most regimens used in the United States have been T-cell replete, whereas a significant proportion of RIC transplantations performed in Europe have used in vivo T-cell depletion (TCD) with either alemtuzumab8 or antithymocyte globulin (ATG).9 Mohty et al10 from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation reported outcomes in 97 adults with ALL and the 42% 2-year leukemia-free survival seen in CR1 patients was encouraging, but only 53 of the 97 patients had early-phase disease. Interestingly, the presence of chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was associated with superior survival (P = .01). The outcome of patients not in remission was dismal. Heterogeneity in the definitions of RIC limits interpretation of some data from this report.

Other groups are prospectively investigating the efficacy of RIC HSCT in adult ALL.11 However, these transplants are being performed in the absence of any large-scale data about outcome and with insufficient knowledge of the prognostic factors that determine that outcome and thus influence the decision to transplantation. There are also limited data to help determine the choice of conditioning regimen and in particular whether TBI should be used. The use of in vivo TCD and the effect of acute and chronic GVHD on relapse and overall outcome also require examination. In this retrospective study using the large multicenter observational database of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), we examined the outcome of RIC and FI conditioning to address these issues.

Methods

Data sources

The CIBMTR is a research affiliation of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry, Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry, and the National Marrow Donor Program established in 2004 that received data from more than 450 transplantation centers worldwide on consecutive allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic HSCT to a Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and the National Marrow Donor Program Coordinating Center in Minneapolis with computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians' review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. The CIBMTR collects both Transplant Essential Data and Comprehensive Report Form data at pretransplantation, 100 days and 6 months after transplantation, and annually thereafter.

Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed with approval of the Institutional Review Boards of the National Marrow Donor Program and the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Patient population

Eligible patients were 16 years of age and older had Ph-ALL in CR1 or CR2 and received a matched sibling or URD HSCT using RIC (n = 93) between 1995 and 2006. They were compared with the 1428 patients who received a myeloablative, FI regimen for ALL. It was anticipated that there would be significant differences between the 2 study populations; thus, adjusted multivariate regression was planned.

The following subgroups were excluded: L3 ALL, HTLV1-associated T-cell, aggressive NK-cell, and large granular lymphocytic leukemia; and also patients with missing or inadequate conditioning regimen or follow-up information. A total of 1428 FI and 93 RIC cases met the on-study criteria from 219 reporting centers in 36 different countries. For 27 patients, conditioning information was missing, and in 6 it was inadequate; these patients were excluded. Median follow-up of survivors was 54 months (range, 3-166 months) for the FI group and 38 months (range, 3-93 months) for the RIC group.

Conditioning regimens and definitions

The CIBMTR definition of RIC has been published12 and included: busulfan 9 mg/kg or less (n = 27), melphalan 150 mg/m2 or less (n = 23), TBI less than 500 cGy single dose or TBI less than 800 cGy fractionated (n = 18), and fludarabine plus TBI dose = 200 cGy (n = 12) and other (n = 13, 6 containing TBI). Most patients in the FI arm received TBI (n = 1252), usually in combination with cyclophosphamide (n = 1037). Smaller numbers had high-dose busulfan (n = 175), usually in combination with cyclophosphamide (n = 142).

Endpoints

Primary endpoints were TRM, morphologic leukemia relapse (hematologic and/or extramedullary), acute and chronic GVHD, DFS, and overall survival (OS). TRM was defined as death during continuous complete remission after transplantation. Relapse was defined as clinical or hematologic leukemia recurrence. For analyses of DFS, failures were clinical or hematologic relapses or deaths from any cause; patients alive and in complete remission were censored at time of last follow-up. For analyses of OS, failure was death from any cause; surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact.

Statistical analysis

Patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related variables among the conditioning regimen groups (RIC vs FI) were compared using the χ2 statistic for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Univariate probabilities of DFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator; the log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons. Probabilities of TRM and relapse were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks.13 Assessment of potential risk factors for outcomes of interest were evaluated in multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards14 or competing hazards regression.15 The variables considered in the multivariate analyses were age at transplantation (< 30 years vs 30-39 years vs 40-49 years vs ≥ 50 years), sex, Karnofsky performance score (KPS; < 80% vs ≥ 80%), lineage (T-cell vs B-cell vs unclassified/other), white blood cells (WBCs, < 25 × 109/L vs 25-100 × 109/L vs > 100 × 109/L), extramedullary disease before HSCT, cytogenetic abnormalities (t(4,11)/t(8:14)/hypodiploid/complex cytogenetics, > 5 abnormalities/others vs no abnormalities),16 CR1 versus CR2, CR1 duration (< 12 months vs ≥ 12 months) for CR2 patients, time from diagnosis to HSCT (< 6 months vs ≥ 6 months) for CR1 patients, TBI in conditioning regimen, type of donor (HLA-identical sibling vs matched URD vs partially matched URD vs mismatched or unknown matching URD), donor-recipient sex match (female-male vs others), donor-recipient cytomegalovirus status (−/− vs others), bone marrow versus granulocyte colony-stimulating factor–mobilized peripheral blood stem cell, GVHD prophylaxis (TCD/ATG or alemtuzumab vs tacrolimus or cyclosporin A-based ± methotrexate ± others vs other), and year of transplantation (1995-2001 vs 2002-2007). The proportional hazard assumption was first tested by adding a time-dependent covariate for each factor. Factors violating the proportionality assumption were adjusted by stratification. A stepwise model selection approach was used to identify all significant risk factors. Each step of model building contained the main effect for conditioning regimen group. Factors that were significant at a 5% level were kept in the final model. The potential interactions between the main effect and all other significant risk factors were tested. Adjusted probabilities of DFS and OS were generated from the final Cox models. All computations were made using the proportional hazards regression procedure in the statistical package of SAS, Version 9. All P values are 2-sided.

Results

Patients and clinical characteristics

The demographic, clinical, and biologic characteristics of 93 RIC and 1428 FI patients who received allogeneic HSCT for ALL are shown in Table 1. The RIC group was older (median, 45 vs 28 years, P < .001). Forty-three percent of the RIC group were 50 years of age and older compared with 7% of the FI group (P < .001). Other factors probably influenced the choice of RIC. Of the 38 RIC patients younger than 40 years, 7 had a KPS less than 80, one had a creatinine more than 2 mg/dL, 10 had a history of fungal disease, 4 had a significant cardiac history, and 13 had pulmonary dysfunction. In total, 23 of 38 patients had at least one of these adverse clinical factors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients 16 years of age or older who underwent a bone marrow and/or peripheral blood HLA-identical sibling or unrelated donor transplantations for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (not L3) in first or second complete remission reported to the CIBMTR between 1995 and 2007

| Patient characteristic | Full intensity, n (%) | RIC, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1428 | 93 | |

| No. of centers | 211 | 57 | |

| Median age, y (range) | 28 (16-62) | 45 (17-66) | < .001 |

| Male sex | 862 (60) | 48 (52) | .10 |

| KPS before transplantation | .07 | ||

| Less than 80% | 106 (7) | 13 (14) | |

| 80% or more | 1262 (88) | 77 (83) | |

| Missing | 60 (4) | 3 (3) | |

| Lineage | .09 | ||

| T cell | 297 (21) | 19 (20) | |

| B cell | 861 (60) | 48 (52) | |

| Other | 270 (19) | 26 (28) | |

| WBC at diagnosis, ×109/L | .61 | ||

| Less than 25 | 715 (50) | 52 (56) | |

| 25-100 | 284 (20) | 19 (20) | |

| More than 100 | 213 (14) | 11 (12) | |

| Missing | 216 (15) | 11 (12) | |

| Extramedullary disease | .72 | ||

| No | 1172 (82) | 77 (83) | |

| Yes | 249 (17) | 15 (16) | |

| Testes | 4 | 0 | |

| CNS | 69 | 4 | |

| Other site | 235 | 14 | |

| Missing | 7 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Cranial radiation | .67 | ||

| No | 1273 (89) | 85 (91) | |

| Yes | 113 (8) | 5 (5) | |

| Missing | 42 (3) | 3 (3) | |

| Conditioning regimen | < .001 | ||

| TBI < 13 Gy | 842 (59) | 38 (41) | |

| TBI ≥ 13 Gy | 413 (29) | 0 | |

| Cyclophosphamide-based | 146 (10) | 19 (20) | |

| Other | 27 (2) | 36 (39) | |

| Cytogenetics | .89 | ||

| t(4;11) ± others | 73 (5) | 5 (5) | |

| Hypodiploid (no t(4;11) or t(8,14)) ± others | 35 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| 5 or more complex abnormalities | 14 (1) | 0 | |

| Others | 440 (31) | 30 (32) | |

| Normal | 485 (34) | 32 (35) | |

| Not tested | 381 (27) | 25 (27) | |

| Disease status before transplantation | .20 | ||

| CR1 | 747 (52) | 55 (59) | |

| CR2 | 681 (48) | 38 (41) | |

| Type of donor | .45 | ||

| HLA-identical sibling | 587 (41) | 30 (32) | |

| Unrelated well matched | 392 (27) | 36 (39) | |

| Unrelated partially matched | 295 (21) | 20 (22) | |

| Unrelated mismatched | 115 (8) | 5 (5) | |

| Unrelated matching unknown | 39 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| Donor-recipient CMV status | .07 | ||

| +/+ | 416 (29) | 23 (25) | |

| +/− | 195 (14) | 7 (8) | |

| −/+ | 339 (24) | 29 (31) | |

| −/− | 437 (31) | 28 (30) | |

| Missing | 41 (3) | 6 (6) | |

| Donor-recipient sex match | .43 | ||

| M-M | 546 (38) | 31 (33) | |

| M-F | 288 (20) | 20 (22) | |

| F-M | 311 (22) | 17 (18) | |

| F-F | 278 (19) | 25 (27) | |

| Missing | 5 (<1) | 0 | |

| Graft type | < .001 | ||

| Bone marrow | 817 (57) | 25 (27) | |

| Peripheral blood | 611 (43) | 68 (73) | |

| Year of transplantation | < .001 | ||

| 1995-2001 | 712 (50) | 25 (27) | |

| 2002-2007 | 716 (50) | 68 (73) | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | .91 | ||

| TCD (ATG or alemtuzumab) | 315 (22) | 20 (22) | |

| Tacrolimus- or CsA-based ± MTX ± other | 1072 (75) | 71 (76) | |

| Other | 41 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors, mo (range) | 54 (3-166) | 38 (3-93) | |

| CR1 | |||

| Time to CR1, wk | .18 | ||

| Less than 4 | 165 (22) | 11 (20) | |

| 4-8 | 307 (41) | 16 (29) | |

| More than 8 | 235 (31) | 23 (42) | |

| Missing | 40 (5) | 5 (9) | |

| Time from diagnosis to transplantation, mo | .14 | ||

| Less than 6 | 430 (58) | 26 (47) | |

| 6 or more | 317 (42) | 29 (53) | |

| Time from CR1 to transplantation, mo | .80 | ||

| Less than 3 | 289 (39) | 19 (35) | |

| 3-6 | 297 (40) | 21 (38) | |

| More than 6 | 118 (16) | 11 (20) | |

| Missing | 43 (6) | 4 (7) | |

| CR2 | |||

| Relapse on chemotherapy | 676 (99) | 36 (95) | .05 |

| Duration of CR1, mo | |||

| Less than 12 | 214 (31) | 10 (26) | .73 |

| 12 or more | 368 (54) | 23 (61) | |

| Missing | 99 (15) | 5 (13) | |

| Time from second CR to HSCT, mo | .73 | ||

| Less than 2 | 349 (51) | 22 (58) | |

| 2-4 | 172 (25) | 10 (26) | |

| More than 4 | 125 (18) | 5 (13) | |

| Missing | 35 (5) | 1 (3) |

Of the 9 patients with t(8;14) or other cytogenetics, 7 patients were B cell, 1 was T cell, and 1 was “other.”

CMV indicates cytomegalovirus; CsA, cyclosporine; MTX, methotrexate; WBC, white blood cell; CNS, central nervous system; TBI, total body irradiation; CR, complete remission; URD, unrelated donor; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; and HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

More RIC patients received peripheral blood grafts (73% vs 43%, P < .001), and more RIC were performed in the more recent time period (73% vs 51%, P < .001). There were no significant differences in other characteristics, including performance status, WBC at diagnosis, poor prognosis cytogenetics, remission status, or percentage of patients with a sibling or well-matched URD.

Hematopoietic recovery and GVHD

Hematopoietic (neutrophil) recovery at day 100 occurred in 98% of the RIC arm and 96% of the FI arm (Table 2, P = .18). There was slightly, but not significantly, more grade II-IV acute GVHD in the FI group (46%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 43%-49% vs 39%, 95% CI, 29%-49%, Table 2, P = .16). Similarly, somewhat more frequent chronic GVHD at 3 years occurred in the FI group (42%, 95% CI, 39%-44% vs 34%, 95% CI, 24%-44%), but this was not statistically significant (Table 2, P = .16). TCD or in vivo T-depleting agents (ATG or alemtuzumab) did not affect engraftment (data not shown) but were associated with a somewhat lower incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD (FI with TCD 42%, 95% CI, 37%-48%, RIC with TCD 30%, 95% CI, 12%-51%, P = .26).

Table 2.

Outcomes after HSCT: univariate analysis

| Full intensity |

RIC |

P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. evaluated | Probability (95% CI) | No. evaluated | Probability (95% CI) | ||

| Hematopoietic (neutrophil) recovery at 100 days | 1388 | 96 (95-97) | 92 | 98 (94-100) | .18 |

| Acute GVHD at 100 days (grade II-IV) | 1427 | 46 (43-49) | 93 | 39 (29-49) | .16 |

| Chronic GVHD at 3 y | 1357 | 42 (39-44) | 90 | 34 (24-44) | .16 |

| Treatment-related mortality | 1409 | 92 | |||

| 1 y | 29 (26-31) | 26 (18-36) | .66 | ||

| 3 y | 33 (31-36) | 32 (23-43) | .86 | ||

| Relapse | 1409 | 92 | |||

| 1 y | 19 (17-21) | 26 (17-35) | .15 | ||

| 3 y | 26 (23-28) | 35 (25-46) | .08 | ||

| DFS at 3 y | 1409 | 41 (38-44) | 92 | 32 (22-43) | .12 |

| OS at 3 y | 1428 | 43 (40-46) | 93 | 38 (28-49) | .39 |

Pointwise P value.

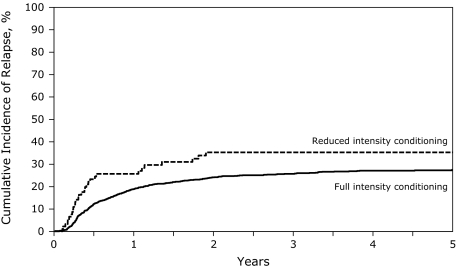

Relapse

The RIC conditioning group did not experience significantly more relapse at 3 years (35% vs 26%, P = .08; Table 2; Figure 1), but comparisons between the 2 groups are difficult. Factors associated with higher relapse rates included transplantation in CR2, particularly with a short (< 12 months) CR1 (short CR1, relapsed risk [RR] of relapse = 2.75; long CR1 > 12 months, RR = 1.51, P < .001; Table 3). The incidence of relapse was lower if there was grade II-IV acute GVHD (RR = 0.54, P = .023), but not with chronic GVHD (RR = 0.80, P = .08). Relapse during CR1 was 21% (95% CI, 18%-24%) for FI and 39% (95% CI, 26%-53%) for RIC (P = .013) compared with CR2 (FI 31%, 95% CI, 28%-35% vs RIC 30%, 95% CI, 17%-46%, P = not significant). TCD did not affect relapse incidence (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of relapse of RIC and FI for adult Ph-ALL.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of TRM and relapse

| Variable | N | RR | Lower CL | Upper CL | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRM, main effect* | |||||

| Full intensity | 1428 | 1.00 | |||

| RIC | 93 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 1.46 | .92 |

| TRM, other significant factors | |||||

| Patient age at transplantation, y | |||||

| Less than 30 | 821 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| 30-39 | 330 | 1.49 | 1.19 | 1.86 | .001 |

| 40-49 | 226 | 1.52 | 1.17 | 1.96 | .002 |

| 50 or more | 144 | 1.89 | 1.36 | 2.63 | < .001 |

| KPS before transplantation | |||||

| Less than 80% | 119 | 1.00 | Poverall = .014 | ||

| 80% or more | 1339 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.87 | .005 |

| Missing | 63 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 1.32 | .37 |

| Disease status before transplantation | |||||

| CR1 | 802 | 1.00 | |||

| CR2 | 719 | 1.35 | 1.11 | 1.63 | .001 |

| Type of donor | |||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 617 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| Unrelated well matched | 428 | 1.11 | 0.86 | 1.44 | .42 |

| Unrelated partially matched | 315 | 1.43 | 1.12 | 1.84 | .005 |

| Unrelated mismatched/unknown | 161 | 2.47 | 1.88 | 3.25 | < .001 |

| Year of transplantation | |||||

| 2002-2007 | 784 | 1.00 | |||

| 1995-2001 | 737 | 1.39 | 1.12 | 1.72 | .003 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |||||

| Tacrolimus- or CSA-based ± MTX ± other | 1340 | 1.00 | Poverall = .012 | ||

| TCD | 126 | 1.45 | 1.09 | 1.90 | .001 |

| Other/none/missing | 55 | 1.03 | 0.61 | 1.76 | .91 |

| Relapse, main effect | |||||

| Full intensity | 1428 | 1.00 | |||

| RIC | 93 | 1.35 | 0.91 | 2.01 | .14 |

| Relapse, other significant factors | |||||

| KPS before transplantation | |||||

| Less than 80% | 119 | 1.00 | .001 | ||

| 80% or more | 1339 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.78 | .001 |

| Missing | 63 | 0.83 | 0.48 | 1.43 | .51 |

| TBI given for conditioning regimen | |||||

| Yes | 1293 | 1.00 | |||

| No | 228 | 1.55 | 1.18 | 2.03 | .002 |

| Disease status before transplantation | |||||

| CR1 | 802 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| CR2, CR1 duration < 12 mo | 224 | 2.75 | 2.12 | 3.57 | < .001 |

| CR2, CR1 duration ≥ 12 mo | 391 | 1.51 | 1.18 | 1.93 | .001 |

| CR2, CR1 duration missing | 104 | 1.29 | 0.85 | 1.97 | .23 |

CL indicates confidence limit.

Stratified variable: graft type.

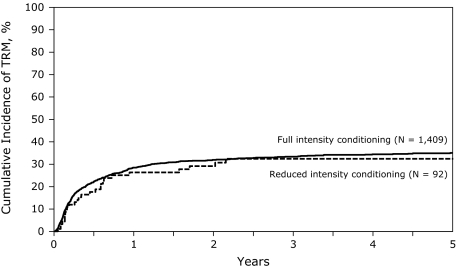

TRM and causes of death

Conditioning regimen intensity had no significant impact on TRM with a similar incidence in the 2 groups (TRM at 3 years, FI 33%, 95% CI, 31%-36% vs RIC 32%, 95% CI, 23%-43%, P = .86; Table 4; Figure 2). However, there may have been other factors that contribute to TRM that differed between the 2 groups. Poor performance status (KPS), transplantation in CR2, and the use of TCD were significantly associated with a higher TRM on multivariate analysis, yet none had a significant interaction with conditioning intensity. Increasing age was associated with a higher TRM, yet in patients older than 40 years, TRM at 3 years was similar in the RIC and FI arms (36% vs 38%, P = not significant). Similarly, donor selection was critical with both partially matched and mismatched URD having higher TRM on multivariate analysis (RR = 1.43 and 2.47, respectively) but did not differ in RIC or FI HSCT. Compared with cyclosporin A or tacrolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis, TCD was associated with a higher 3-year TRM (RR = 1.45, P = .001) (FI 44%, 95% CI, 38%-50% vs RIC 35% 95% CI, 15%-59%; Table 3). Thirteen patients with KPS less than 80 were treated with RIC, and 6 died of TRM (48%, 95% CI, 22%-75%) at 3 years.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of treatment failure (death or relapse) and death

| Variable | N | RR | Lower CL | Upper CL | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment failure, main effect | |||||

| Full intensity | 1421 | 1.00 | |||

| RIC | 92 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 1.41 | .75 |

| Treatment failure, other significant factors | |||||

| Patient age at transplantation, y | |||||

| Less than 30 | 820 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| 30-39 | 327 | 1.32 | 1.12 | 1.56 | .001 |

| 40-49 | 223 | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.67 | .002 |

| 50 or more | 143 | 1.65 | 1.29 | 2.11 | < .001 |

| KPS before transplantation | |||||

| Less than 80% | 118 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| 80% or more | 1333 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.77 | < .001 |

| Missing | 62 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 1.23 | .37 |

| TBI as part of conditioning regimen | |||||

| Yes | 1285 | 1.00 | |||

| No | 228 | 1.40 | 1.16 | 1.68 | .001 |

| Disease status before transplantation | |||||

| CR1 | 795 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| CR2, CR1 duration < 12 mo | 224 | 1.92 | 1.59 | 2.33 | < .001 |

| CR2, CR1 duration ≥ 12 mo | 390 | 1.46 | 1.23 | 1.73 | < .001 |

| CR2, CR1 duration missing | 104 | 1.42 | 1.09 | 1.84 | .01 |

| Type of donor | |||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 610 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| Unrelated well matched | 428 | 1.07 | 0.89 | 1.28 | .50 |

| Unrelated partially matched | 314 | 1.24 | 1.03 | 1.50 | .02 |

| Unrelated mismatched/unknown | 161 | 1.96 | 1.58 | 2.43 | < .001 |

| Year of transplantation | |||||

| 2002-2007 | 783 | 1.00 | |||

| 1995-2001 | 730 | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.46 | .003 |

| Death, main effect | |||||

| Full intensity | 1421 | 1.00 | |||

| RIC | 92 | 0.92 | 0.69 | 1.24 | .60 |

| Death, other significant factors | |||||

| Patient age at transplantation, y | |||||

| Less than 30 | 820 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| 30-39 | 327 | 1.38 | 1.16 | 1.63 | < .001 |

| 40-49 | 223 | 1.49 | 1.22 | 1.81 | < .001 |

| 50 or more | 143 | 1.88 | 1.46 | 2.42 | < .001 |

| KPS before transplantation | |||||

| Less than 80% | 119 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| 80% or more | 1339 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.78 | < .001 |

| Missing | 63 | 0.82 | 0.56 | 1.20 | .31 |

| WBC at diagnosis, ×109/L | |||||

| Less than 25 | 764 | 1.00 | Poverall = .003 | ||

| 25-100 | 301 | 1.25 | 1.04 | 1.49 | .017 |

| More than 100 | 224 | 1.40 | 1.15 | 1.71 | .001 |

| Missing | 224 | 1.17 | 0.96 | 1.42 | .12 |

| TBI as part of conditioning regimen | |||||

| Yes | 1285 | 1.00 | |||

| No | 228 | 1.44 | 1.20 | 1.73 | < .001 |

| Disease status before transplantation | |||||

| CR1 | 795 | 1.00 | |||

| CR2 | 718 | 1.69 | 1.46 | 1.96 | < .001 |

| Type of donor | |||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 610 | 1.00 | Poverall < .001 | ||

| Unrelated well matched | 428 | 1.11 | 0.92 | 1.34 | .26 |

| Unrelated partially matched | 314 | 1.34 | 1.12 | 1.61 | .002 |

| Unrelated mismatched/unknown | 161 | 2.13 | 1.72 | 2.63 | < .001 |

| Year of transplantation | |||||

| 2002-2007 | 783 | 1.00 | |||

| 1995-2001 | 730 | 1.26 | 1.08 | 1.47 | .003 |

CL indicates confidence limit.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality of RIC and FI for adult Ph-ALL.

Causes of death are shown in Table 5. Relapse was the most common cause of death and was slightly more common in the RIC group (46% vs 34%, P = not significant). Infection was the next most common cause, followed by GVHD (5% in the RIC group vs 11% in the FI patients).

Table 5.

Causes of death

| Full intensity | RIC | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 1428 | 93 |

| No. of deaths | 817 | 56 |

| Leukemia relapse | 282 (34) | 26 (46) |

| Infection | 132 (16) | 7 (13) |

| GVHD | 88 (11) | 3 (5) |

| Organ failure and toxicity | 179 (22) | 9 (16) |

| Hemorrhage | 32 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Graft rejection | 16 (2) | 0 |

| Other | 88 (11) | 9 (16) |

Survival

Despite the older age in the RIC group, OS and LFS at 3 years were similar to those receiving FI HSCT (Table 2; Figures 3–4; supplemental Figure 1; available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). However, the differences between the 2 conditioning groups again suggest caution in interpreting the direct comparisons. Age younger than 30 years was associated with significantly better survival, and the RR of death increased with each additional decade. Other factors associated with improved survival were a higher KPS, WBC less than 25 000/μL at diagnosis, the use of TBI in the conditioning regimen, and HSCT using a sibling or well-matched URD. Of the 13 patients treated with RIC who had a KPS less than 80, only 1 survives leukemia-free. No factors that significantly influenced survival showed a significant interaction with conditioning intensity.

Figure 3.

Adjusted probability of DFS of RIC and FI for adult Ph-ALL.

Figure 4.

Adjusted probability of OS of RIC and FI for adult Ph-ALL.

Survival for HSCT in CR1 at 3 years was similar in both cohorts (FI 51%, 95% CI, 48%-55% vs RIC 45%, 95% CI, 31%-59%) and in CR2 (FI 33%, 95% CI, 30%-37% vs RIC 28%, 95% CI, 14%-44%). In addition, DFS was similar for FI vs RIC conditioning in both CR1 (FI 49%, 95% CI, 45%-53% vs RIC 36%, 95% CI, 23%-51%) and in CR2 (FI 32%, 95% CI, 29%-36% vs RIC 27, 95% CI, 14%-43%), although smaller numbers in the RIC group limit the power of the comparisons (supplemental Figure 2).

Discussion

The results of therapy for adult ALL are globally unsatisfactory. Allografting has an important and growing role in its management, but the outcomes of this treatment modality still need improvement, particularly for older patients where FI regimens lead to excess TRM and unsatisfactory survival.1 Advances will probably come from better patient and donor selection, but also from exploring safer conditioning protocols. The main finding of our study was that the RIC group experienced survival similar to the FI group despite a substantially older median age. RIC transplantations can be performed in patients with high-risk ALL with reasonable TRM and survival. Reducing the intensity of conditioning was not associated with a significant increase in relapse, although a larger study would be required to demonstrate any small differences in relapse rates. It is possible that pretransplantation chemotherapy intensity or minimal residual disease differed between the 2 groups, but these data were not available for analysis. Importantly, the time to transplantation was similar, suggesting that the number of induction and consolidation cycles administered before HSCT were similar as well.

Although originally anticipated to reduce toxicity, as seen in many other studies,7 TRM for the older RIC group was comparable with that seen in the younger FI cohort. The Medical Research Council/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study reported 35% 2-year TRM for FI sibling transplantations in patients older than 35 years. The 32% 3-year TRM we observed in sibling and well-matched URD RIC allograft patients warrants further study. Comorbidities (assessed in this study only as lower KPS) and older age both had significant adverse effects on TRM. TRM was higher in patients with less well-matched URD; and as reported from Minnesota,11,17 the use of cord blood donors after either RI or FIC deserves investigation in patients with ALL. The use of ATG, albeit in limited numbers (n = 37) of patients, appeared to increase TRM and remains unexplained. It is notable that a multicenter United Kingdom study of alemtuzumab-based conditioning in myeloablative transplantations reported excellent survival and very low TRM.18

ALL is the last major leukemia in which RIC allografting has been investigated. RIC relies on an immune graft versus tumor effect, and some have doubted the clinical potency of that effect in ALL. Although there is a clear and strong graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect with some studies showing a 2.5-fold reduction in relapse in patients with GVHD,19–21 it is also postulated that RIC may not achieve the minimal residual disease state where this GVL effect could be operative. Although we found only modestly reduced relapse in patients with acute GVHD, this study does provide further evidence of a GVL effect because, even with less intense conditioning, low relapse rates and promising DFS were observed. However, relapse remains frequent, and investigation of posttransplantation maintenance strategies may be of value.

Heterogeneity in patients confounds the interpretation of this and other series describing RIC allografting in adult ALL. In this analysis, we did not detect a beneficial effect of chronic GVHD on survival, even though approximately one-third of patients in each cohort developed chronic GVHD. More patients in the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation series had received ATG (39% vs 20%).10

Martino et al22 reported 27 high-risk adult ALL patients (44% alternative donor, 85% beyond CR1, 44% chemorefractory, 41% Ph+) who had a 31% 2-year survival. Massenkeil et al9 from Berlin reported 9 patients with 44% survival after fludarabine, busulphan, and ATG conditioning. Hamaki et al23 from Tokyo reported 33 patients (20 siblings, 13 alternative donors) given fludarabine/busulphan and ATG conditioning (19 in remission and 14 refractory) with a 30% 1-year relapse-free survival. Stein et al7 from City of Hope reported 22 patients given fludarabine and melphalan conditioning using either sibling or URD, and this resulted in excellent survival at 1 year after transplantation. These reports suggest that more than 30% of patients survive through the highest risk period and that TRM ranges from 4% to 27%.

This study has some limitations that should influence data interpretation. The number of patients treated with RIC allografts in CR1 and CR2 (n = 93), although the largest reported, is still relatively small, and it should be noted that they were transplanted at 57 centers using various conditioning regimens.24 More of the RIC group received a transplantation after 2002 (73% vs 51%), and more received peripheral blood stem cell grafts. Given the number of patients in the RIC arm, the study was not powered sufficiently to detect a 10% difference in relapse (35% vs 25%). There was also an undoubted selection bias in ALL patients chosen for either FI or RIC HSCT, and the reasons for selected RIC are not always apparent. Further research is required to determine the preferred conditioning regimens and, in particular, whether the use of TBI, even at low dose, improves outcomes.

These data suggest that RIC conditioning is worthy of further investigation in prospective clinical trials of adult ALL. These trials should include both well-matched URD and related donors and should be confined to patients in remission. Caution should be exercised in the most difficult clinical situations (patients with a poor performance status and those with less well-matched donors); thus, careful consideration of other available approaches is required. Adult Ph− ALL is a rare disease. Multicenter and probably multinational collaboration is required to define further the role of RIC allografting in this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Mitchell Cairo, Steven C. Goldstein, Luis Isola, Michael Lill, Mark Litzow, Richard T. Maziarz, Alan Miller, Bipin Savani, Gary Schiller, Tsiporah B. Shore, Brian Bolwell, Joachin Deeg, Alison W. Loren, Gustavo A. Milone, Harry C. Schouten, Robert Soiffer, Michael Bishop, Roger Herzig, Osman Illhan, Dipnarine Maharaj, and Reinhold Munker for helpful comments and insights.

The CIBMTR is supported by the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518); the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and National Cancer Institute (Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294); the Health Resources and Services Administration (contract HHSH234200637015C); the Office of Naval Research (grants N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058); and AABB; Aetna; American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; Amgen Inc; anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US Inc; Baxter International Inc; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; Be the Match Foundation; Biogen IDEC; BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc; Biovitrum AB; BloodCenter of Wisconsin; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Bone Marrow Foundation; Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group; CaridianBCT; Celgene Corporation; CellGenix GmbH; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Children's Leukemia Research Association; ClinImmune Labs; CTI Clinical Trial and Consulting Services; Cubist Pharmaceuticals; Cylex Inc; CytoTherm; DOR BioPharma Inc; Dynal Biotech, an Invitrogen Company; Eisai Inc; Enzon Pharmaceuticals Inc; European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; Gamida Cell Ltd; GE Healthcare; Genentech Inc; Genzyme Corporation; Histogenetics Inc; HKS Medical Information Systems; Hospira Inc; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Kiadis Pharma; Kirin Brewery Co Ltd; Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Merck & Company; Medical College of Wisconsin; MGI Pharma Inc; Michigan Community Blood Centers; Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc; Miller Pharmacal Group; Milliman USA Inc; Miltenyi Biotec Inc; National Marrow Donor Program; Nature Publishing Group; New York Blood Center; Novartis Oncology; Oncology Nursing Society; Osiris Therapeutics Inc; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc; Pall Life Sciences; Pfizer Inc; Saladax Biomedical Inc; Schering Corporation; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; StemCyte Inc; StemSoft Software Inc; Sysmex America Inc; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; THERAKOS Inc; Thermogenesis Corporation; Vidacare Corporation; Vion Pharmaceuticals Inc; ViraCor Laboratories; ViroPharma Inc; and Wellpoint Inc.

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the US government.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: D.I.M. and D.J.W. designed the study and prepared the manuscript; T.W. and W.S.P. performed the statistical analysis; and J.H.A., E.C., R.P.G., B.G., V.G., J.H., H.J.K., T.R.K., H.M.L., V.A.L., P.M., D.A.R., M.S., J.S., and M.S.T. participated in interpretation of data and approval of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel J. Weisdorf, University of Minnesota Medical Center, 420 Delaware Street SE, MMC 480, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: weisd001@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993). Blood. 2008;111(4):1827–1833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks DI, Perez WS, He W, et al. Unrelated donor transplants in adults with Philadelphia-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission. Blood. 2008;112(2):426–434. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): an MRC UKALL12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood. 2007;109(3):944–950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop MR, Logan BR, Gandham S, et al. Long-term outcomes of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after autologous or unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation: a comparative analysis by the National Marrow Donor Program and Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(7):635–642. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks DI, Forman SJ, Blume KG, et al. A comparison of cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation with etoposide and total body irradiation as conditioning regimens for patients undergoing sibling allografting for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first or second complete remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(4):438–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks DI, Aversa F, Lazarus HM. Alternative donor transplants for adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a comparison of the three major options. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(7):467–475. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein AS, Palmer JM, O'Donnell MR, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for adult patients with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(11):1407–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kottaridis PD, Milligan DW, Chopra R, et al. In vivo CAMPATH-1H prevents graft-versus-host disease following nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2000;96(7):2419–2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massenkeil G, Nagy M, Neuburger S, et al. Survival after reduced-intensity conditioning is not inferior to standard high-dose conditioning before allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation in acute leukaemias. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36(8):683–689. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohty M, Labopin M, Tabrizzi R, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective study from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2008;93(2):303–306. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachanova V, Verneris MR, DeFor T, Brunstein CG, Weisdorf DJ. Prolonged survival in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after reduced-intensity conditioning with cord blood or sibling donor transplantation. Blood. 2009;113(13):2902–2905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giralt S, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimen workshop: defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(3):367–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein J, Moeschberger M. Survival Analysis: Techniques of Censored and Truncated Data. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Statist Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial. Blood. 2007;109(8):3189–3197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomblyn MB, Arora M, Baker KS, et al. Myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: analysis of graft sources and long-term outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3634–3641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel B, Kirkland KE, Szydlo R, et al. Favorable outcomes with alemtuzumab-conditioned unrelated donor stem cell transplantation in adults with high-risk Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission. Haematologica. 2009;94(10):1399–1406. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.008649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiden PL, Flournoy N, Thomas ED, et al. Antileukemic effect of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of allogeneic-marrow grafts. N Engl J Med. 1979;300(19):1068–1073. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905103001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Passweg JR, Tiberghien P, Cahn JY, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia effects in T lineage and B lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21(2):153–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, Storb R, et al. Influence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease on relapse and survival after bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical siblings as treatment of acute and chronic leukemia. Blood. 1989;73(6):1720–1728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martino R, Giralt S, Caballero MD, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a feasibility study. Haematologica. 2003;88(5):555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamaki T, Kami M, Kanda Y, et al. Reduced-intensity stem-cell transplantation for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective study of 33 patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35(6):549–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.