Abstract

This multi-method study examined the association between family instability and children’s internal representations of security in the family system within the context of maternal communications about disruptive family events. Participants included 224 kindergarten children (100 boys and 124 girls) and their parents. Parents reported on the frequency of unstable family events, mothers reported their patterns of communication to children following disruptive events, and children completed a story-stem battery to assess their internal representations of family security. Consistent with predictions, heightened family instability was associated with less security in child representations. The implication of these results for notions of children’s security in the family system, including exploratory findings on the protective role of maternal communications for children’s representations, are discussed.

Keywords: risk, representations, communication, parenting, adversity

Family instability, characterized by the disruptive events (e.g., changes in caregiver intimate relationships, residential mobility, caregiver changes) that threaten the consistency, coherence, and security of the family unit from the child’s perspective, has been associated with elevated psychological problems (Ackerman, Kogos, Youngstrom, Schoff, & Izard, 1999; Adam & Chase-Lansdale; 2002 Forman & Davies, 2003). Conceptualizations of why family instability poses a risk to children’s mental health have commonly focused on children’s difficulties attaining emotional security in the face of repeated family disruptions (e.g., Ackerman et al., 1999; Bretherton, Walsh, Lependorf, & Georgeson, 1997). In these models, family instability is proposed to threaten children’s sense of security by undermining the predictability and continuity of family experiences. However, little empirical effort has been devoted to examining children’s security in the context of family instability. Guided by emotional security theory (EST; Davies & Cummings, 1994), the primary objective of this study was to examine associations between family instability and children’s sense of security in the family system.

In accordance with the concept of working models and scripts in attachment and family systems literatures (Bretherton, 1990; Byng-Hall, 2002; Marvin & Stewart, 1990), EST theorizes that children’s ability to preserve the goal of security is reflected in their internal representations of family experiences. Internal representations of family life are defined as scripts children develop about the meaning and implications that family relationships and events have for their own welfare. Family volatility may engender negative internal representations of the family as children increasingly rely on their appraisals as maps for identifying and defending against future threats in the family (Johnston & Roseby, 1997; Cummings & Davies, 1996). Thus, insecurity in the face of family instability may be manifested in child representations of stressful events as substantially compromising the quality of the specific family relationship, proliferating to disrupt broader family processes, and undercutting children’s confidence in their ability to maintain their well-being (Davies & Cummings, 1994).

Despite the theoretical precedence for expecting associations between family instability and children’s insecure representations of the family, most extant research has focused on symptom-based child outcomes and has not explicitly tested this hypothesis. As an exception, Forman and Davies (2003) documented a modest path between family instability and adolescents’ insecure appraisals of family (i.e., β = .17). Although this first foray into identifying processes underlying the risk of family instability raised several intriguing questions, further research is required to draw confident conclusions about the findings. For example, reliance on a single method (i.e., questionnaires) in this study may have artificially inflated relationships among family instability and child representations of the family. Likewise, the focus on young adolescents leaves questions about the generalizability of associations between family instability and insecure representations of the family at other developmental periods. Therefore, a main aim of this study was to extend this work by examining associations between family instability and insecure representations within a multi-method measurement strategy. In addition, we focused on the early-school-year period because it may be a particularly sensitive time for family instability as children struggle with worries about unsettling events and their implications while increases in social perspective taking amplify children’s concerns about safety (Cicchetti, Cummings, Greenberg, & Marvin, 1990).

A secondary aim of this study was to contextualize the risk posed by family instability within a broader multivariate model. The modest magnitude of the association between family instability and children’s functioning in prior research (e.g., Ackerman et al., 1999; Forman & Davies, 2003) underscores heterogeneity in the outcomes of children who are exposed to similar levels of family instability. Thus, a key task is to identify sources of variability, particularly resilience, in the functioning of children who experience heightened instability. Through their communications with their children about family disruptions, parents may play a pivotal role in modulating the nature and magnitude of vulnerability children experience in contexts of family instability. If safety and security are among the most salient in the hierarchy of human goal systems as the EST suggests, explicating how parental communications about stressful or challenging circumstances may alter the magnitude of risk is a pressing research direction. Accordingly, this study explored how mothers’ communication with children about unstable family events might moderate the impact of family instability on children. Age-appropriate messages designed to guide children’s understanding and foster optimistic, secure conceptions of the family in the face of disruptive family events may help bolster children’s confidence in the family to overcome challenges (Eisenberg et al., 2001; Garner, Jones, Gaddy, & Rennie, 1997; Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994) and therefore buffer the impact of instability on children. However, the limited research conducted to date does not consistently support this hypothesis (e.g., Gomulak-Cavicchio, Davies, & Cummings, 2006; Winter, Davies, Hightower, & Meyer, 2006). Therefore, the aim of examining maternal communication about family disruption as a moderator of family instability is exploratory.

In summary, this study advances the predominant empirical focus on associations between family instability and children’s symptomatology. Our main aim was to examine whether family instability was associated with security in young children’s representations of the family within a multi-method design. In addition, we explored the role of maternal communication to children about disruptive events as a moderator of associations between family instability and child representations.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from the second wave of an investigation that included mothers, fathers, and kindergarten children recruited from elementary schools or community organizations at two sites (Rochester, NY and South Bend, IN, US). Ninety-five percent (n=224) of the original 235 families participated in the second wave one year later. Child participants included 100 boys and 124 girls (M age 6.97 years; SD=0.48). Seventy-five reported being European American, 15% African American, 4% biracial, 1% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% Arabic, 1% American Indian, and 4% Hispanic. The mean number of years of education completed was 14.5 (SD=2.32) for mothers and 14.6 (SD=2.71) for fathers, while median annual household income was $40,000–$54,000. The majority of parents reported being biological mothers (87%) and fathers (95%), and 85% reported being married, 5% cohabitating with partner, 4% single/not married or cohabitating, 1% divorced, and 2% separated.

Procedure

Families visited the lab for two visits spaced one week apart. Consent and assent were first obtained, through institutional review board approved procedures, with participants being informed of their rights to abstain and withdraw at any time without penalty. Parents then completed questionnaires to assess demographic information and family instability (visit 1), mothers reported on their communication patterns, and children reported on their representations (visit 2). Due to time limitations, no data were collected on paternal communications.

Measures

Family instability

Mothers and fathers completed an adaptation of the Family Instability Questionnaire (FIQ; Forman & Davies, 2003; Ackerman et al., 1999). The FIQ asks caregivers to report on the cumulative occurrences of eight disruptive family events over the past three years across domains of (a) caregiver changes, (b) residential changes, (c) caregiver intimate relationship changes, (d) job/income loss, and (e) family member death. The validity of FIQ is supported by its theoretically meaningful ties to child adjustment (Forman & Davies, 2003). Based on their significant correlation (r=.48), mother and father reports were averaged into a family instability composite

Maternal communication patterns

Maternal communication patterns were assessed using the semi-structured Family Events Interview, in which interviewers presented five hypothetical vignettes depicting disruptive family events: parental job loss, interparental problems, family member death, residential change, and substance abuse in the family. Following each vignette, mothers were asked if their children would see her react to the situation and if so, “How would your distress be expressed to [Child]?” Next, mothers were asked whether they would say anything (verbally) to children, and if yes, “What would you say to [Child]?” Interviewers recorded responses on paper.

Based on prior research (Winter et al., 2006), responses were coded for the degree to which maternal reactions were likely to convey, from a child’s perspective, that the family is able to maintain safety, stability, and cohesion in the face of adverse events. Each verbal explanation was rated along three five-point continuous scales. First, Security ratings ranged from (1) Strong Insecurity, characterized by verbalizations likely to significantly increase the sense of threat the event poses to the child, to (5) Strong Security, verbalizations likely to alleviate threat. Second, ratings on the Caregiver Competence code ranged from (1) Very Incompetent, with caregiver(s) represented as vulnerable or frightening, to (5) Very Competent, with caregiver(s) portrayed as able to cope and protect the family. Third, the Family Cohesion code was rated from (1) Very Discordant explanations depicting interpersonal relationships as pervasively discordant or threatening, to (5) Very Harmonious, with explanations depicting relationships as consistently harmonious. In addition to the verbal communication codes, the mother’s behavioral and verbal responses were coded on a global scale of Emotional Communication Quality. Ratings ranged from (1) Very Low, in which the reaction pattern highlighted lack of protection and was likely to amplify the stressfulness of the event, to (5) Very High, in which the response pattern depicted caregiver(s) as able to respond in a protective manner and therefore were likely to allay child concerns.

Given our interest in communication patterns, mothers who indicated that they would not display a verbal or emotional reaction to more than three vignettes (n=5) were dropped from coding and analyses. All remaining narratives were coded by two independent raters who were unaware of family status on the other constructs. Inter-rater reliability, indexed by intraclass correlation coefficients, ranged from .85–1.0 (M = .98), so ratings were averaged across rater. To obtain indices of mothers’ overall patterns of responding, we aggregated across ratings for each of the codes across the five vignettes. Principal component analysis with varimax rotation on the four codes yielded one factor (based on eigenvalue >1 and scree plot inspection), with loadings of the four indicators ranging from .67 to .92. Therefore, codes were standardized and averaged to obtain an assessment of Communication Optimism (α = .83). The validity of this measure is supported by its links with family discord and child representations (Winter et al., 2006).

Children’s family representations

To assess child representations of family relationships in the face of challenges, children completed seven narrative story stems using the general presentation format of the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (Bretherton, Oppenheim, Buchsbaum, Emde, and the MacArthur Narrative Group, 1990). Stories were intended to assess three family subsystems: mother-father (e.g., conflict about lost keys), mother-child (e.g., mother-child separation then reunion) and father-child relationships (e.g., disagreement over activities) (see Davies, Sturge-Apple, Winter, Cummings, & Farrell, 2006). Each stem, plus warm-up and debriefing stems, were presented by experimenters using props and family dolls matched to the ethnicity of family members and the child’s gender. The experimenter gave the props and dolls to the child and asked him/her to “Show me and tell me what happens next.”

Videotaped responses were coded using three five-point scales from an established system designed to assess child security in the family (Davies et al., 2006; Winter et al., 2006). First, the Overall Felt Security code was rated from: (1) Strong Insecurity, depicting the stressor as presenting a long-term, severe threat to security, to (5) Strong Security, portraying the family as competently resolving the stressor while regulating negative affect, maintaining family harmony, and protecting the child. Second, Caregiver Competence ratings averaged across mother and fathers ranged from (1) Strong Incompetence, portraying caregiver(s) as frightening or inept and unable to protect the child, to (5) Strong Competence, portraying caregivers as utilizing resources to promote child security. Third, Family Discord ratings ranged from (1) Strong Harmony, portraying supportive, harmonious family relationships, to (5) Strong Discord, depicting long-term or intense problems in family relationships. Inter-rater reliability, indexed by intraclass correlation coefficients, ranged from .78 to .99 (M = .91) for 25% of independently coded videotapes. After aggregating ratings across vignette to obtain parsimonious indices of children’s representations, we formed a single assessment of Child Secure Representations of the family by averaging Security, Caregiver Competence, and Family Discord (reverse scored) scores (internal consistency, α = .95). Validity for the scales is supported by their associations with other forms of family adversity and children’s adjustment (Davies et al., 2006).

Results

Descriptive analysis of the family instability index indicated that caregivers reported a mean of 3.35 disruptive events (SD = 3.12) during the preceding three year period. The proportion of families who experienced at least one incident of each of the family disruptive events was as follows: family member death (46%); residential move (46%); job loss (34%); primary caregiver change (22%); people moving in or out (13%); dissolution (7%) or beginning (6%) of intimate adult relationship; and romantic partner moving into the home (5%). Consistent with hypotheses, correlational analyses revealed that family instability was associated with less secure child representations, r(223) = −.14, p < .05, and less optimistic maternal communications about disruptive family events, r(216) = −.15, p < .05. Moreover, maternal optimistic communication was positively associated with child secure representations of the family, r(215) = .15, p < .05

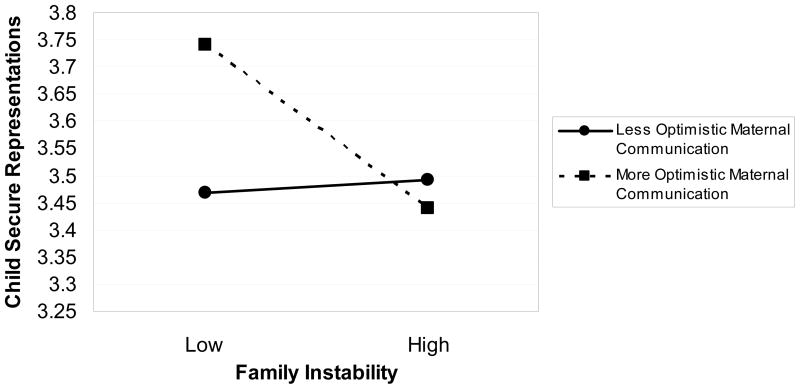

The proposed moderator model was tested in a hierarchical regression analysis following conventional procedures for testing interactions (Aiken & West, 1991). Child security was uniquely predicted by both instability [F (2, 214) = 3.27, p = .07, β= −.12] and communicated optimism [F (2, 214) = 3.50, p = .06, β= .13] at a trend level. The product term was significant after controlling for the main effects of each variable, F (3, 214) = 3.73, p = .05, β= −.13, r2 =.05. The plot of the interaction shown in Figure 1 indicates that children exhibited the most secure representations of the family when more optimistic maternal communications were accompanied by relatively low levels of family instability. In further support of the plot, simple slope analyses revealed that the association between maternal communication and child representations was significant at low, F (3, 214) = 7.27, p < .01, β = .25, r2 = .05, but not high levels of family instability, F (3, 214) = .17, ns.

Figure 1.

The Interaction of Family Instability and Maternal Optimistic Communication Predicting Children’s Secure Representations.

Discussion

Although prior research has documented that children exposed to heightened family instability are disproportionately at risk for experiencing psychopathology, little is known about the conditions and mechanisms underlying this vulnerability. Guided by emotional security conceptualizations (Ackerman et al., 1999; Forman & Davies, 2003; Hetherington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998), our principal aim was to examine the relationship between family instability and child representations of security in the family. Consistent with predictions, heightened family instability was associated with lower security in children’s internal representations of the family. According to the theoretical framework of EST, a primary goal for children is preserving a sense of security within the broader family system, which is affected by the ability of the family unit to provide a consistent, predictable, and dependable socialization context (Forman & Davies, 2003). Therefore, heightened family instability threatens children’s sense of security by undermining the predictability and continuity of family experiences and manifesting in insecure representations of the family. Interpreted within this framework, our results indicate that children exposed to heightened instability were more likely to interpret events as having deleterious consequences for family welfare and stability.

However, the replication of the modest magnitude of the relationship between family instability and child representations underscores the importance of examining family instability in the context of other family processes. Accordingly, a second objective of this investigation was to explore whether parental communication about disruptive family events moderated the association between family instability and children’s representational analyses of the meaning of family events for themselves and their families. Indeed, findings indicated that the multiplicative interplay between maternal optimistic communication and family instability was associated children’s secure representations of the family. By the same token, the nature of the interaction was not consistent with the more classic form of protective effect in which the association between family instability and lower levels of children’s secure representations of the family is significantly diminished when mothers endorse more optimistic communications with their children about disruptive family events. Rather, findings indicated that children’s confidence in their family as a haven of safety and cohesion was most pronounced when maternal optimistic communications about the ability of the family to withstand disruptions were consistent with experiences of low levels of family instability (see Figure 1). Thus, consistent with more fine-grained taxonomies of protective factors, optimistic communication was best characterized as playing a “protective but reactive” role whereby its advantages are most evident at low, rather than high, levels of adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000).

There are several plausible explanations for these findings. First, the risk associated with heightened instability may simply be too great for optimistic communications to confer a marked developmental advantage for children (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Thus, the toxic nature of experiencing recurrent breakdowns in the cohesiveness and stability of the family may undercut children’s confidence in the family as a source of safety and security regardless of how parents communicate with children about the meaning of the disruptive events (Forman & Davies, 2003). Second, children’s assimilation of optimistic communications about disruptive events may depend on whether the optimistic parental messages are easily reconciled with their histories of experience with family adversity. Therefore, children’s internalization of the family as a hub of support and warmth may be facilitated when there is congruence between their actual experiences in a cohesive family context and their exposure to caregiver communications emphasizing the ability of the family to successfully weather stressful family events. Third, socialization formulations have postulated that children are more likely to assimilate parental messages in stable, secure network of family relationships (Bretherton et al., 1997; Grusec & Goodnow, 1994). Thus, in homes characterized by stability, the higher levels of trust and confidence children have in parents may increase their motivation and ability to accept parental optimistic messages in a way that manifests in secure representations of the family.

However, it is important to interpret the findings of this study in context of its limitations. First, the ecological validity of the maternal communication measure may be limited by our use of an analogue assessment. Although parents, in all likelihood, tailor what they say to children based on their perceived needs and emotional states of their children (Denham, 1998), our interview assessment does not fully capture the dynamic, transactional process of parent-child discussions of stressful events (Barrett, 1997). Likewise, the hypothetical vignettes comprising this new measure may have captured parental intentions rather than actual responses. However, consistent with the prior use of analogue assessments in the family discord literature (Cummings, Goeke-Morey, & Dukewich, 2001), the validity of our assessment is supported by associations between maternal communications and family risk factors and child functioning in substantively meaningful ways. Moreover, analog procedures afford control over stimuli and measurement that offset limitations (e.g., internal validity) inherent in other forms of measurement. Nevertheless, our assessment of maternal communications about family instability should be interpreted with caution and complemented by the development of other methods of capturing parent-child communication patterns. Given the unique role of fathers in the socialization of children (Cummings & O’Reilly, 1997), assessing paternal as well as maternal communication patterns is another important direction for future research.

Second, our findings are qualified by sampling and design issues. Although the sociodemographic characteristics of our sample of families were comparable to the characteristics of families within the geographical areas of the research sites, our sample was predominantly white and middle to lower middle class. Thus, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to high risk samples. In addition, although our cross-sectional design is an appropriate first step in the early stages of a research program, comprehensive tests of the hypotheses will require prospective studies.

Despite limitations, findings from this study support the notion that family instability can challenge young, school-age children’s sense of emotional security in the family environment (Davies & Cummings, 1994). For children, the family is the primary source of protection and stability. When the family context is instead associated with chaos and unpredictability, children may be left with a lack of confidence in the family as able to provide a predictable, secure environment. Accordingly, findings underscore the role of family instability in children’s adaptation at the level of appraising threat and family security in disruptive events. Furthermore, our results support the hypothesis that child adaptation may depend on the context in which children experience maternal communications about disruptive family events. Although caution should be exercised in translating the findings to clinical practice and public policy until the results can be replicated, the findings highlight the importance of refraining from recommending a generic, one-size-fits-all solution to allaying children’s concerns about the impact of disruptive family events. In support of this message, our results indicated that maternal endorsement of optimistic communications about the ability of the family to withstand disruptive family events was only associated with secure representations of the family when children experienced low levels of family instability.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health fellowship F31MH0680572 awarded to Marcia Winter and R01MH57318 awarded to Patrick Davies and E. Mark Cummings. We are grateful to the children and parents who participated in this project. Our gratitude is also expressed to the project staff, including Courtney Forbes, Courtney Henry, Amy Keller, Michelle Sutton, Alice Schermerhorn, and the student research assistants at the University of Rochester and University of Notre Dame.

Contributor Information

Marcia A. Winter, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester

Patrick T. Davies, Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology, University of Rochester

E. Mark Cummings, Department of Psychology, University of Notre Dame.

References

- Ackerman BP, Kogos J, Youngstrom E, Schoff S, Izard C. Family instability and the problem behaviors of children from economically disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:258–268. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam EK, Chase-Lansdale PL. Home sweet home(s): Parental separations, residential moves, and adjustment problems in low-income adolescent girls. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:792–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KC, editor. The communication of emotion: Current research from diverse perspectives. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Communication patterns, internal working models, and the intergenerational transmission of attachment relationships. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1990;11:237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Walsh R, Lependorf M, Georgeson H. Attachment networks in postdivorce families: The maternal perspective. In: Atkinson L, Zucker KJ, editors. Attachment and psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 97–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Oppenheim D, Buchsbaum H, Emde RN The MacArthur Narrative Group . MacArthur story stem battery. 1990. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Byng-Hall J. Relieving parentified children’s burdens in families with insecure attachment patterns. Family Process. 2002;41:375–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, Greenberg MT, Marvin RS. An organizational perspective on attachment beyond infancy: Implications for theory, measurement, and research. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 51–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Emotional security as a regulatory process in normal development and the development of psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Dukewich TL. The study of relations between marital conflict and child adjustment: Challenges and new directions for methodology. In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, O’Reilly AW. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality on child adjustment. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1997. pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Winter MA, Cummings EM, Farrell D. Child adaptational development in contexts of interparental conflict over time. Child Development. 2006;77:218–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Emotional development in young children. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Losoya S, Guthrie IK, Murphy B, Shepard SA, Padgett SJ, Fabes RA, Poulin R, Reiser M. Parental socialization of children’s dysregulated expression of emotion and externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:183–205. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman EM, Davies PT. Family instability and young adolescent maladjustment: The mediating effects of parenting quality and adolescent appraisals of family security. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:94–105. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Jones DC, Gaddy G, Rennie KM. Low income mothers’ conversations about emotions and their children’s emotional competence. Social Development. 1997;6:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gomulak-Cavicchio BM, Davies PT, Cummings EM. The role of maternal communication patterns about interparental disputes in associations between interparental conflict and child psychological maladjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;35:757–771. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9050-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Impact of parental discipline methods on the child’s internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM. What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children’s adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53:167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JR, Roseby V. In the name of the child: A developmental approach to understanding and helping children of conflicted and violent divorce. New York: Free Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guideline for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin RS, Stewart RB. A family systems framework for the study of attachment. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 51–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein J, West SJ. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Child Development. 1994;65:1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter MA, Davies PT, Hightower AD, Meyer SC. Relations among family discord, caregiver communication, and children’s family representations. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:348–351. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]