Abstract

Mycoplasma hominis is a fastidious micro-organism causing genital and extragenital infections. We developed a specific real-time PCR that exhibits high sensitivity and low intrarun and interrun variabilities. When applied to clinical samples, this quantitative PCR allowed to confirm the role of M. hominis in three patients with severe extragenital infections.

Mycoplasma hominis are fastidious bacteria, which are not detected on routinely used axenic media [1]. Lack of a cell wall makes these organisms naturally resistant to β-lactam antibiotics and not detectable by Gram staining. M. hominis is a recognized agent of genital infections in adults as well as of neonatal infections [2, 3]. Furthermore, it has been reported as the etiologic agent of various serious extra-genital infections such as brain abscess, pneumonia, mediastinitis, pericarditis, endocarditis, osteitis, arthritis, wound infections, peritonitis, and pyelonephritis both in immunosuppressed and in immunocompetent individuals [4–11]. Since most commonly used antibiotics in clinical practice are not active against M. hominis, the diagnosis of infections due to this fastidious bacterium is a crucial issue, especially for extra-genital cases.

In this context, we developed a real-time PCR assay for the detection of M. hominis. Then, this new PCR was applied to clinical samples obtained from patients suffering from extra-genital M. hominis infections.

A forward primer MhF (5-TTTGGTCAAGTCCTGCAACGA-3′, position 2472–2493 of GenBank sequence AF443616), a reverse primer MhR (5′-CCCCACCTTCCTCCCAGTTA-3′, position 2553–2572 of AF443616), which amplifies a 101 bp part of the 16S rRNA-encoding gene, and a minor-groove binder probe labeled with 5′ VIC (TACTAACATTAAGTTGAGGACTCTA, position 2513–2537 of AF443616) were selected using the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). The reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 μl, including 0.2 μM of each primer, 0.2. μM of probe, 10 μl 2× TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and 5 μl of DNA sample. The cycling conditions were 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C, followed by 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. An ABI Prism 7900 instrument (Applied Biosystems) was used for the amplification and detection of the PCR products. The specificity of the real-time PCR was high, being increased by the use of a TaqMan probe. No cross-amplification was observed when 5 ng of genomic DNA of humans, fungus (Candida albicans ATCC 10231), and 15 different bacterial strains were tested (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Ureaplasma parvum, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Gardnerella vaginalis, Lactobacillus sp., Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus agalactiae). A plasmid containing the target gene was constructed to perform the quantification step, as described previously [12].

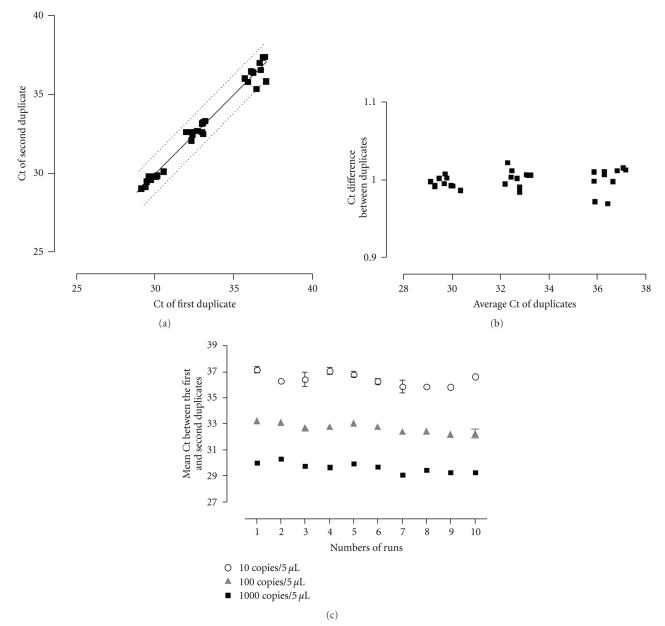

Duplicates of 10-fold serial dilutions of the plasmid were run in ten independent experiments in order to analyze the sensitivity and the reproducibility of the PCR results. As shown in Figure 1(a), the intrarun reproducibility was excellent. As expected, intrarun variability was slightly higher at very low concentration of target DNA (Figure 1(b)). The interrun variability was low, except at a low concentration of 10 plasmid copies per 5 μl (Figure 1(c)). Thus, the mean Ct values +/−1 standard deviation were of 29.64 +/− 0.38 (1.28%), 32.69 +/− 0.36 (1.10%), and 36.43 +/− 0.49 (1.34%) for 1000, 100, and 10 DNA copies per 5 μl. The analytical sensitivity of the real-time PCR was 10 copies of plasmid control DNA per reaction mixture, that is, similar to the light-cycler PCR already reported by Baczynska et al. [14]. This sensitivity is about 10-fold better than the 16SrRNA broad-range PCR developed by Bosshard et al. [15]. When testing genomic DNA obtained by growing M. hominis in culture, we again obtained an excellent sensitivity which was of about 1000 bacteria/ml. When serially diluting a clinical sample (inguinal abscess of patient 1), the eubacterial PCR was slightly positive when the real-time specific Mycoplasma PCR was positive with a Ct of 33.4 (45 copies in 5 μl of DNA) whereas eubacterial PCR was negative when the real-time specific Mycoplasma PCR was positive with a Ct of 36.3 (6.5 copies in 5 μl of DNA).

Figure 1.

Intra and interrun reproducibility of the real-time PCR assessed on duplicate of plasmid positive controls performed at 10-fold dilutions from 1000 to 10 plasmid copies/5 μL during 10 successive runs. (a) Plots of the cycle threshold (Ct) of first and second duplicates, showing intrarun variability of the real-time PCR between duplicates of positive plasmid controls; 95% confidence interval is shown by the dashed lines. (b) Bland-Altman graph showing the ratio of Ct of both duplicates according to the mean of the Ct of duplicates. (c) Plots of the mean of duplicate of plasmid positive controls according to each successive run, showing the low interrun variability of the real-time PCR. Standard deviations show the intrarun reproducibility of the PCR.

Since growing evidence supports the role of M. hominis as an emerging agent of extra-genital infections, the real-time PCR was tested in 34 clinical samples taken from 15 patients suffering from various extra-genital infections. These samples included physiologically sterile sites such as pleural fluid, percardial fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and cardiac valve (n = 19) and from samples potentially contaminated with oropharyngeal flora (n = 15), that is, mainly respiratory tract samples (n = 8). DNA was extracted from 200 μl of samples using the MagNAPureLC automated system (Roche) and the MagnaPureLC DNA isolation kit 1 (Roche). DNA was eluted in a final volume of 100 μl of the elution buffer provided in the kit. A negative extraction control (DNA free water extracted in parallel of the specimen) was tested for each extraction run. Each sample was amplified in duplicate. Inhibition control (specimen spiked with 1 μl containing 200 plasmid copies) and negative PCR mixture control were systematically tested. All samples were investigated because of clinical suspicion except two, for which the presence of M. hominis DNA was already detected by a broad spectrum 16SrRNA PCR directly performed on the specimens [16]. Both were confirmed positive by the new PCR with very high bacterial load (Table 1). DNA of M. hominis was also found in samples of 1 out of the 13 remaining patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of three patients with Mycoplasma hominis extra-genital infections, including clinical presentation and results of the real-time PCR.

| Patient no. | Age | Sex | Clinical infection | Underlying conditions | Other etiology | Clinical specimen | M. hominis qPCR results in copies/mL | Other positive diagnostic tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | Female | Inguinal lymphadenitis with abscess formation | Neutropenia, HIV | None | Abscess fluid a | 16,175,000 | Specific culturec and broad-spectrum PCR |

| Cervix swab | 4,400 | |||||||

| Vaginal swab | 130 | |||||||

| Urine | 82 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 15 | Female | Pneumonia and pericarditis | None | None | Abscess fluid a | 98,500,000 | Specific culturec and broad-spectrum PCR |

| Pleural fluid | 380,000 | |||||||

| Pericardiac fluid | 85 | |||||||

| Sputumb | 6 | |||||||

| Pleural fluidb | 0 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 56 | Male | Mediastinitis | Type A aortic dissection | None | Mediastinal fluid a | 7,000 | Blood agar d |

| Mediastinal swab | 460 | |||||||

| Blood | 5 | |||||||

a First samples documenting the infection;

b Samples taken a few days after treatment start;

cCulture media: Mycoplasma IST, bioMérieux, France;

d Conventional culture positive on blood agar plate followed by sequencing for identification [13].

For all 3 positive patients, DNA of M. hominis was detected in ≥3 specimens (Table 1). Moreover, for each of these 3 patients, at least one of the positive molecular results was further confirmed by culture with a commercial media (Mycoplasma IST, bioMérieux, France) or on blood agar (thin layer of bacteria and sequencing for identification) [13]. Due to the high level of conservation of the 16S rRNA, our real-time PCR is likely amplifying any member of the M. hominis group that includes M. salivarium, M. orale, and M. arginii. All cases presented in this paper were M. hominis sensu stricto as confirmed by sequencing 16S rRNA encoding gene. The clinical presentation of these three cases is summarized in Table 1.

In conclusion, we developed a new PCR that exhibited high sensitivity and that allowed us to diagnose or confirm three extra-genital cases of M. hominis infections, which may remain undetected due to the fastidious growth of this bacterium. Recently, Masalma et al., using a cloning and/or pyrosequencing sequencing approach, also identified two extragenital M. hominis cerebral infections [4]. The advantage of their strategy is the broad spectrum of the approach that is not limited to Mycoplasma whereas the advantages of our real-time PCR are simplicity, rapidity, and lower risk of contamination.

This new real-time PCR represents an efficient tool for the diagnosis of M. hominis infections that may contribute to better defining of the prevalence and pathogenicity of M. hominis. Moreover, it could help to improve clinical outcomes of severe extra-genital infections in patients not responding to commonly used beta-lactam antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

G. Greub is supported by the Leenards Foundation through a career award entitled “Bourse Leenards pour la Relève Académique en Médecine Clinique à Lausanne”. The authors thank Ph. Tarr for reviewing this paper. A. Pascual and K. Jaton contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Waites KB, Robinson T. Mycoplasma and ureaplasma. In: Murray PR, editor. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. Washington, DC, USA: ASM Press; 2007. pp. 1004–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor P. Medical significance of mycoplasmas. Methods in Molecular Biology. 1998;104:7–15. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-525-5:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waites KB, Katz B, Schelonka RL. Mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas as neonatal pathogens. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2005;18(4):757–789. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.4.757-789.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masalma MA, Armougom F, Scheld WM, et al. The expansion of the microbiological spectrum of brain abscesses with use of multiple 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(9):1169–1178. doi: 10.1086/597578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenollar F, Gauduchon V, Casalta JP, Lepidi H, Vandenesch F, Raoult D. Mycoplasma endocarditis: two case reports and a review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2004;38(3):e21–e24. doi: 10.1086/380839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García C, Ugalde E, Monteagudo I, et al. Isolation of Mycoplasma hominis in critically ill patients with pulmonary infections: clinical and microbiological analysis in an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine. 2007;33(1):143–147. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon GM, Alspaugh JA, Meredith FT, et al. Mycoplasma hominis pneumonia complicating bilateral lung transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Chest. 1997;112(5):1428–1432. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.5.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marini H, Merle V, Frébourg N, et al. Mycoplasma hominis wound infection after a vascular allograft. Journal of Infection. 2008;57(3):272–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mechai F, Le Moal G, Duchêne S, Burucoa C, Godet C, Freslon M. Mycoplasma hominis osteitis in an immunocompetent man. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2006;25(11):715–717. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norton R, Mollison L. Mycoplasma hominis pneumonia in Aboriginal adults. Pathology. 1995;27(1):58–60. doi: 10.1080/00313029500169472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SS-Y, Yuen K-Y. Acute pyelonephritis caused by Mycoplasma hominis . Pathology. 1995;27(1):61–63. doi: 10.1080/00313029500169482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaton K, Bille J, Greub G. A novel real-time PCR to detect Chlamydia trachomatis in first-void urine or genital swabs. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2006;55(12):1667–1674. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petti C, Bosshard P, Brandt M, et al. Interpretative criteria for identification of bacteria and fungi by DNA target sequencing. Approved Guideline. 2008;28(12) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baczynska A, Svenstrup HF, Fedder J, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. Development of real-time PCR for detection of Mycoplasma hominis . BMC Microbiology. 2004;4, article no. 35 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosshard PP, Kronenberg A, Zbinden R, Ruef C, Böttger EC, Altwegg M. Etiologic diagnosis of infective endocarditis by broad-range polymerase chain reaction: a 3-year experience. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;37(2):167–172. doi: 10.1086/375592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldenberger D, Künzli A, Vogt P, Zbinden R, Altwegg M. Molecular diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis by broad-range PCR amplification and direct sequencing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1997;35(11):2733–2739. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2733-2739.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]