Introduction

Lifestyle, in relation to the prevalence of overweight in children, is a public health concern (1-3). Behavioral change constructs, such as goal-setting, self-efficacy, and readiness for change, need to be applied to the development of educational materials to address obesity in children (4, 5). Educational games can promote goal-setting, enhance motivation, and build self-efficacy in overweight preadolescents (5). The United States Department of Agriculture provides interactive MyPyramid- For Kids materials for children age 6-11 years on its website (6), but these materials do not address the children's readiness to make changes or self-efficacy in promoting intake goals.

We adapted components from the Weight, Activity, Variety, and Excess (WAVE) Pocket Card and Screeners (7,8) to develop a game-like tool for introducing goal setting to overweight children entering a weight management program. Our goal was to enhance motivation before introducing the MyPyramid recommendations.

Methods

The instrument development and evaluation protocol was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board. We obtained verbal parental consent and child assent to participate in the formative evaluation.

Instrument Development

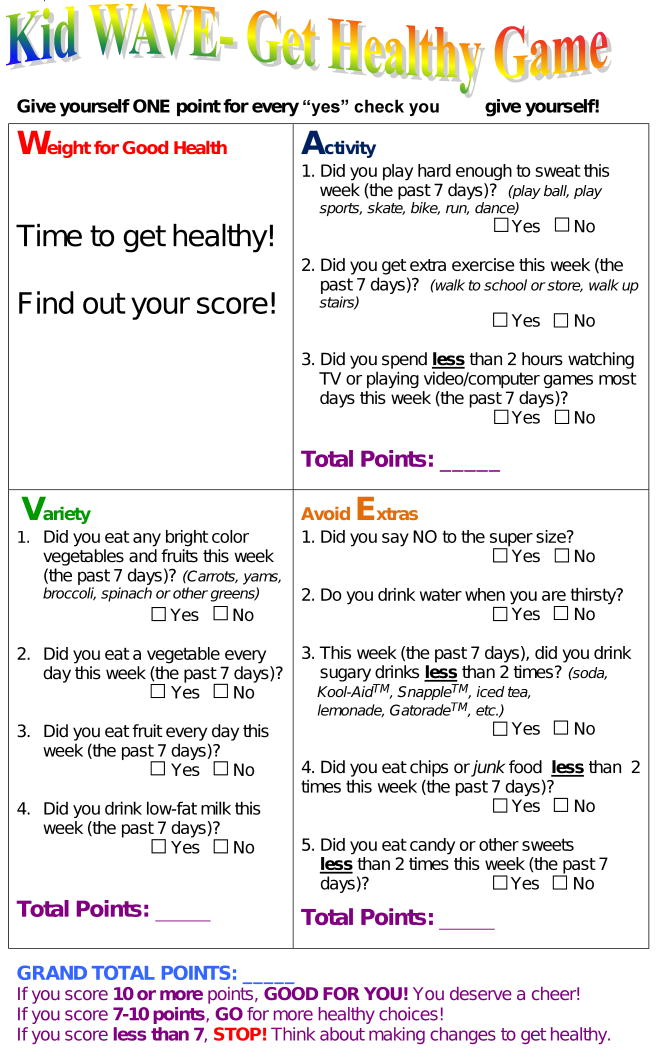

We used the original WAVE Pocket Card template [7] as the format for the KidWAVE: Get Healthy Game. The weight quadrant is not scored while the other quadrants include 3-5 items with a corresponding score range of 3-5 points. Each of the scored quadrants includes one or more items related to lower body mass index (BMI) z-scores among children in a clinical weight loss program or related to trying to lose weight among Bronx 5th graders on the WAVE screener, which includes items adapted from the Youth Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (YBRFS) (8). The items addressed Activity – watching less TV (p <0.05), Variety – switching from regular to low fat milk (p < 0.01), and Excess – less juice (p<0. 01), less sugary drinks (p< 0.01), less regular soda (p< 0.05), and less junk food. (p< 0.001). Other items were chosen based on MyPyramid recommendations but without emphasizing the number of servings to achieve the sense of mastery (eg, vegetables due to the exceedingly low initial intake). The maximum potential score is 12 points. The assessment was designed as a self-scoring tool with subtotals for each quadrant for the child to then calculate a total score.

Formative Evaluation

The template and scoring system were reviewed by 2 dietitians, 1 health psychologist, 2 pediatricians, and 2 elementary school teachers to address the content, scoring system, perceived appeal, and ease of completion. We evaluated acceptability and feasibility of using the card in an inner-city clinic setting where the vast majority of parents are Spanish speakers, but the children prefer communication in English.

We used cognitive interviewing to assess understanding and refine the format. We pilot tested the card by asking children (n=53) to complete the card and to respond to a 7-item evaluation while waiting for appointments in a large municipal hospital pediatric primary care clinic program. To evaluate user-friendliness, we asked the children to indicate if completing the card was fun and if it felt like a game. We also asked if it made them want to get more points, be a healthy weight, be more active, eat a variety of food, and avoid excess junk food and soda. Response options were definitely yes, probably yes, probably no and definitely no. We evaluated responses dichotomously as yes or no.

Calculation of readability scores

Card readability determined the grade of school reading level (Flesch-Kincaid, Microsoft Word version 2003, 2003).

Results and Discussion

Responses to the cognitive interviews indicated that most of the children could tell how often they ate a food but had difficulty conceptualizing recommendations with regard to servings per day. They often named vegetables when asked what fruits they ate and vice-versa. Other areas that needed to be clarified included the length of a week (eg, number of days) or what was meant by last week. Most of the children needed prompting to complete the self-scoring part of the sections, but after prompting they calculated scores without assistance.

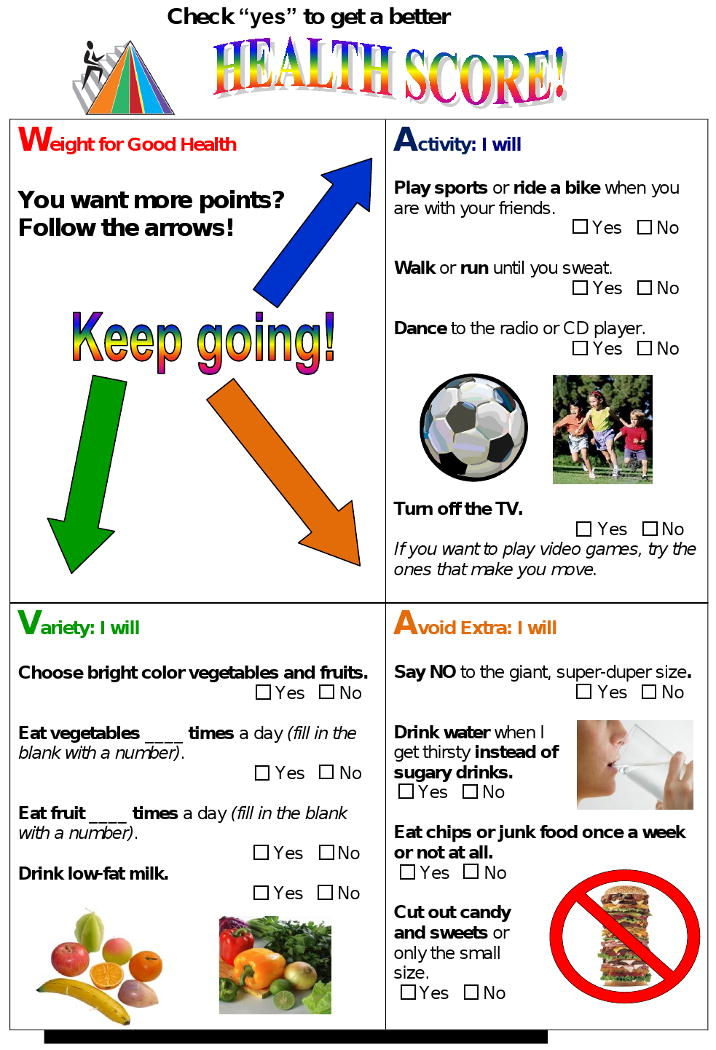

Children completed the card in 5-15 minutes, which included selecting strategies to improve their score. The self-assessment by children (n=53) in the pilot testing indicated that 20/53 (38%) did not consume a vegetable daily during the previous week, 28/53 (53%) did not consume a fruit daily, and 29/53 (55%) did not drink low-fat milk. The children's responses to the evaluation questions indicated that 50/53 (94%) had fun, 47/53 (88%) felt like they were playing a game, and 52/53 (98%) reported that completing it made them want to get more points. With regard to questions about whether the completing the questions motivated health behaviors, 52-53/54 (98-100%) responded with yes to wanting to be at a healthy weight, be more active, and eat a greater variety of food, while 44/53 (83%) responded with yes to wanting to avoid excess junk food and soda. The KidWAVE: Get Healthy Game, illustrated in Figures 1 (front – assessment) and Figure 2 (back – behavioral goals), appears to be easy to read (with a Flesch-Kincaid grade level of 2.9 suggesting that it could be easily read by the majority of children at the end of second grade).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Clinical Application and Implications for Nutrition Educations

We are using the card to initiate goal-setting in a family weight management program. It will be followed by a more in-depth education in subsequent sessions with MyPyramid materials geared for 6-11 year olds. The KidWAVE-Get Healthy Game can be used to introduce children to the importance of a healthy lifestyle and to increase their awareness of physical activity, dietary variety, and excesses, all of which are important achieving a healthy body weight. This tool is accessible as a Word file from http://eph.aecom.yu.edu/web/division_details.aspx?id=6

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R18DK075981, the Diabetes Research and Training Center P60 DK020541, and Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1 RR025750. We thank Renee Rosett for her helpful feedback and suggestions during the development and formative evaluation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Middleman AB, Vazquez I, Durant RH. Eating patterns, physical activity, and attempts to change weight among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French SA, Lin BJ, Guthrie JF. National trends in soft drink consumption among children and adolescents age 6 to 17 years: prevalence, amounts, and sources, 1977/1978 to 1994/1998. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1326–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)01076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003-2006. JAMA. 2008;299:2401–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckman H, Hawley S, Bishop T. Application of theory-based health behavior change techniques to the prevention of obesity in children. J Ped Nurs. 2006;21:266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maddison R, Foley L, Mhurchu CN, et al. Feasibility, design and conduct of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial to reduce overweight and obesity in children: The electronic games to aid motivation to exercise (eGAME) study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Department of Agriculture. [August 22, 2009]; MyPyramid.gov-For Kids Available at; www.mypyramid.gov/KIDS.

- 7.Barner C, Wylie-Rosett Gans K. WAVE: a pocket guide for a brief nutrition dialogue in primary care. Diabetes Educ. 2001;27:352–8. 361–2. doi: 10.1177/014572170102700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isasi CR, Soroudi N, Wylie-Rosett J. Youth WAVE Screener: addressing weight-related behaviors with school-age children. Diabetes Educ. 2006;(32):415–22. doi: 10.1177/0145721706288763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]