Abstract

Notch1 receptor signaling regulates oligodendrocyte progenitor differentiation and myelin formation in development, and during remyelination in the adult CNS. In active multiple sclerosis lesions, Notch1 localizes to oligodendrocyte lineage cells, and its ligand Jagged1 is expressed by reactive astrocytes. Here, we examined induction of Jagged1 in human astrocytes, and its impact on oligodendrocyte differentiation. In human astrocyte cultures, the cytokine TGFβ1 induced Jagged1 expression, and blockade of the TGFβ1 receptor kinase ALK5 abrogated Jagged1 induction. TGFβ2 and β3 had similar effects, but induction was not observed in response to the TGFβ family member activin A or other cytokines. Downstream, TGFβ1 activated Smad-dependent signaling, and Smad-independent pathways that included PI3 kinase, p38 and JNK MAP kinase, but only inhibition of the Smad-dependent pathway blocked Jagged1 expression. SiRNA inhibition of Smad3 downregulated induction of Jagged1, and this was potentiated by Smad2 siRNA. Purified oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) nucleofected with Notch1 intracellular signaling domain displayed a shift towards proliferation at the expense of differentiation, demonstrating functional relevance of Notch1 signaling in OPCs. Furthermore, human OPCs plated onto Jagged1-expressing astrocytes exhibited restricted differentiation. Collectively, these data illustrate the mechanisms underlying Jagged1 induction in human astrocytes, and suggest that TGFβ1-induced activation of Jagged1-Notch1 signaling may impact the size and differentiation of the OPC pool in the human CNS.

Keywords: Notch, autoimmunity, multiple sclerosis, CNS repair

Introduction

The pathology of multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by CNS inflammation, demyelination and oligodendrocyte loss, progressive axonal transection, and a reactive astrogliosis (Raine, 1997). Demyelination is associated with conduction block in affected axons and clinical symptoms (Brück and Stadelmann, 2005), and also with axonal loss in chronic lesions, which is associated with permanent clinical deficit (Trapp et al., 1998). Remyelination restores conduction and is associated with functional recovery (Smith et al., 1979), but often fails with disease progression. Endogenous remyelination is believed to depend on a pool of committed oligodendrocyte progenitors (OPCs) (Gensert and Goldman, 1997), thus the mechanisms that regulate the numbers and differentiation of these cells, and hence the extent of myelin formation, are of particular interest in research into MS therapy.

Examination of mechanisms underlying myelin repair has revealed that pathways regulating developmental myelination may also be sensitive to reactivation in the adult (Hinks and Franklin, 1999; Wu et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2004; Fancy et al., 2009). We previously reported an example of this phenomenon (John et al., 2002). In the embryonic CNS, signaling via the Notch pathway regulates OPC differentiation and proliferation (Wang et al., 1998; Genoud et al., 2002), and we showed that this pathway is reactivated in active MS plaques (John et al., 2002). Until recently, the relevance of Notch signaling in OPCs in the postnatal CNS remained unclear (Stidworthy et al., 2004; Seifert et al., 2007). However, recent studies using Olig1Cre:Notch112f/12f mice, in which Notch1 is inactivated throughout the oligodendrocyte lineage, revealed that the Notch pathway is one of the mechanisms regulating the rate of OPC differentiation during CNS remyelination (Zhang et al., 2009).

Activation of Notch1 and Notch2 receptors is induced via contact-mediated binding of ligands including Jagged1 and 2 and Delta1-4 (Kopan and Ilagan, 2009). In active MS lesions, we found that Notch1 and its effector Hes5 localize to oligodendrocyte lineage cells, while Jagged1 is expressed by reactive GFAP+ astrocytes (John et al., 2002). Other groups have confirmed Jagged1 and Notch1 expression in the CNS in demyelinating animal models (Stidworthy et al., 2004; Seifert et al., 2007). In human astrocytes, we have implicated the cytokine TGFβ1 in Jagged1 induction in astrocytes, but the signaling pathways involved have not yet been investigated. Here, we show that TGFβ1-mediated induction of Jagged1 in human astrocytes is mediated via the receptor kinase ALK5 and the transcription factor Smad3, with Smad2 playing a more minor role. Our data suggest that TGFβ1-activated Smad-independent signaling pathways do not contribute significantly to Jagged1 induction. We further demonstrate that Jagged1-Notch1 signaling from human astrocytes to OPCs restricts oligodendrocyte differentiation and is permissive for proliferation. These findings are compatible with and extend our previous work (John et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2009). They define the mechanisms underlying Jagged1 induction in human astrocytes, and suggest that activation of Jagged1-Notch1 signaling may impact the size and differentiation state of the oligodendrocyte progenitor pool in the human CNS.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Culture

Postmortem human CNS tissue was obtained from the Human Tissue Repository at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Clinical Review Committee. Cultures of primary human astrocytes were established and maintained as described (John et al., 2002). Human cultures enriched for oligodendrocytes were prepared as previously reported (Wilson et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006). Rodent OPC cultures were prepared from P1 rat cortices by immunopanning for A2B5+ Ran2− cells and propagated or differentiated as previously described (Caporaso and Chao, 2001; Gurfein et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009).

Cytokines/Growth Factors

Recombinant human TGFβ1, -2 and -3 and IL-1β were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hills, NJ), and used at 1 or 10ng/ml based on dose-response studies that we and others have performed previously on cytokine-mediated signal transduction (John et al., 2002). Other cytokines and growth factors shown in Figure 1 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and used at 1–100ng/ml (10ng/ml shown). Insulin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used at 5μg/ml.

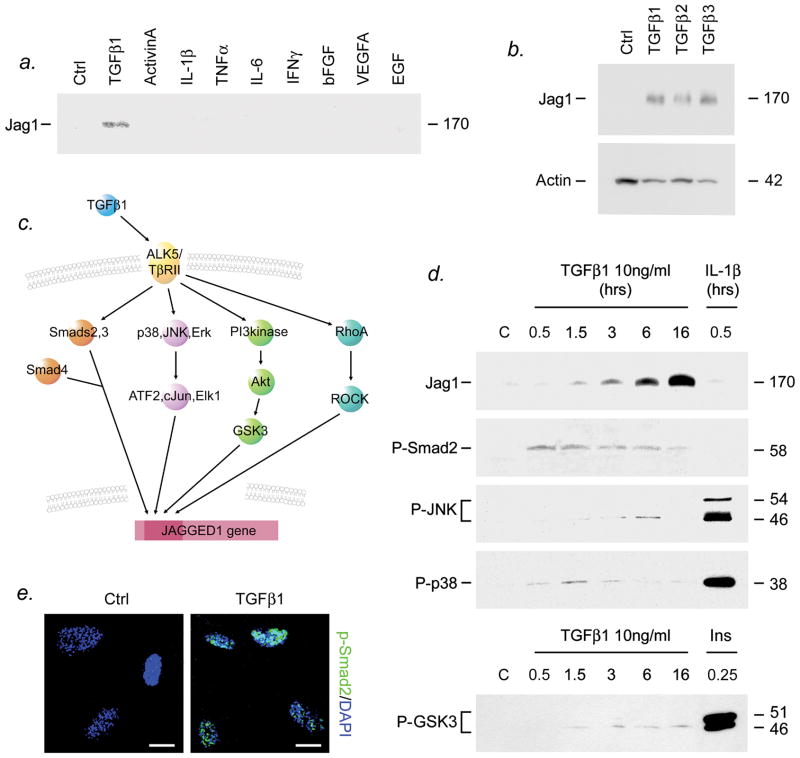

Figure 1. TGFβ1 activates Smad-dependent and -independent signaling and induces Jagged1 in human astrocytes.

(a,b) Primary human astrocytes were treated with cytokines and growth factors shown at a final concentration of 10ng/ml, then at 24h subjected to immunoblotting. Jagged1 was observed as a band at 170kD in response to treatment with 10ng/ml TGFβ1 (a), and was also induced in response to TGFβ2 or TGFβ3 (b). No other factors tested had any detectable effect (a). (c) TGFβ1 has been shown to activate Smad-dependent signaling and Smad-independent pathways (Shi and Massagué, 2003). In primary human astrocytes, TGFβ1 (10ng/ml) induced Smad2 phosphorylation (d) and nuclear translocation (e, 60min illustrated), and activation of the Smad-independent p38, JNK and Erk MAP kinase and PI3 kinase pathways (d). TGFβ1 also induced expression of Jagged1, first observed at 90min and reaching a plateau at 16hrs (d). Activation of JNK (phosphorylation at Thr183/Tyr185) was delayed and transient relative to other pathways tested, and was observed as a 46kD band solely at 6h. Scalebar, (e) 4μm. Data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments in separate cultures.

DNA Constructs

An expression construct for the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) was the gift of Dr. Rafael Kopan (Washington University, St. Louis, MO) (Schroeter et al., 1998). The Hes1 luciferase reporter pGa981-6 has been described previously (Minoguchi et al., 1997). The human Jagged1 expression construct pcDNA3hJag1 was the gift of Dr. Linheng Li (Stower’s Research Institute, Kansas City, MO) (Li et al., 1997).

Inhibitors

The ALK5 inhibitors SB431542 and TGF Receptor Inhibitor II, MAP kinase inhibitors SB203580 (p38), JNK Inhibitor II and PD98059 (Erk), and ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 were from EMD Bioscience. Inhibitors of the PI3 kinase-Akt pathway CI-MADCC (Akt) and LY294002 (PI3 kinase) were from Calbiochem and Sigma. Concentrations used were based on results of previous studies (Laping et al., 2002; John et al., 2004), and preliminary experiments confirmed that these inhibited Notch signaling without inducing significant cell death.

Antibodies

Goat anti-human Jagged1 and rabbit anti-Jagged1 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit anti-phospho-Smad2 (Ser465/467), Smad2, Smad3, phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), SAPK/JNK, phospho-p38(Thr180/Tyr182), p38, phospho-GSK-3α/β(Ser21/9), GSKα - Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The A2B5 mouse hybridoma was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and its antibody (IgM) prepared using standard methods. Other antibodies: O4 mouse monoclonal IgM (Dr. Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY); monoclonal mouse anti-CNPase (IgG1) and rabbit polyclonal anti-Olig2 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Rat anti-Notch1 (IgG1) and rat anti-Notch2 (IgG1) were from the Developmental Hybridoma Studies Bank at the University of Iowa (donated by Dr. Spyros Artavanis-Tsakonas, Harvard Medical School).

Immunoblotting

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting were performed as previously published (John et al., 2004).

Immuofluorescence

Cells were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at times specified, and processed for single- or double-immunostaining for A2B5 (1:15), O4 (1:25), CNPase (1:100), MBP (1:100), Olig-2 (1:100), Notch1 (1:50) and Notch2 (1:50), using combinations described in the text. For all antigens except A2B5 and O4, cells were blocked with 10% goat serum 0.3% Triton-PBS (TPBS) 30 min, and incubated with primary antibody in TPBS 1% goat serum overnight at 4°C. After rinsing in PBS, cells were incubated in secondary antibodies (1:100, Invitrogen-Molecular Probes), 1hr RT, then rinsed with TPBS, counterstained with DAPI and mounted. In the case of A2B5 and O4, cells were stained without permeabilization using detergent-free buffer, then permeabilized to allow subsequent double staining for intracellular antigens (Zhang et al., 2006). Immunostained cultures were examined and photographed using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal system attached to an Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY). Z-series stacks were collected using 1μm on the Z-axis and assembled into projections. Morphometric analysis was performed on random fields (at least 5 per condition) using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD), and results subjected to statistical analysis (see below).

Transfection

PcDNA3hJag1 (1ng, see above) or vector control were cotransfected into human astrocyte cultures with a GFP expression construct (pEGFP) using Superfect (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stable lines were established using G418 selection as previously described (John et al., 2002).

Nucleofection

NICD expression construct (1ng, see above) or empty vector control was nucleofected into A2B5+ Ran2− OPCs using an Amaxa nucleofector with the Basic Neuron Kit (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NICD activity was confirmed in parallel experiments using co-nucleofection of the Hes1 luciferase reporter pGa981-6, followed by luciferase assay carried out as below.

SiRNA

Human astrocytes were plated to 70% confluence, then transfected with a total concentration of 5nM siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) using TransIT-TKO (Mirus, Madison, WI) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24h, cells were serum-starved for 6h, then treated as described. Controls included non-targeting siRNA and sham control (transfection reagent alone). The extent and specificity of gene silencing were assessed by immunoblotting.

TGFβ bioassay

Mink lung epithelial cells (MLEC) stably expressing firefly luciferase under the control of a TGF-β–sensitive portion of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) promoter were a gift from Dr. D. Rifkin (New York University) and have been described previously (Abe et al., 1994). To measure active TGFβ levels in astrocyte-conditioned medium, MLEC were plated into 6-well plates at 7.5 × 105 cells/well, then 12h later exposed to conditioned medium from primary human astrocyte cultures, or unconditioned medium control. To measure total (active plus latent) TGFβ, conditioned medium and controls were heated for 5min at 80°C. In all cases, MLEC were incubated in conditioned medium or control for 16h, then washed and luciferase levels measured as below.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

Cells were harvested with 300μl reporter lysis buffer (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), then 20μl of lysate was added to 100μl of luciferase substrate (Boehringer-Mannheim) for 10sec and relative light units (RLU) determined using a Lumat LB luminometer (Berthold).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of quantitated results was performed using Prism software v4.0 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). For multiple comparisons, ANOVA plus Bonferroni post test was used. For comparisons between two groups, we used Student’s t test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

TGFβ1 induces Jagged1 expression in primary human astrocytes

To determine the stimuli required for Jagged1 induction in human astrocytes, we analyzed responses of primary cultures to cytokines and growth factors relevant to CNS inflammation and/or progenitor differentiation (Figure 1). Protein extracts were harvested from treated cultures and controls at 24h, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (Fig. 1a). Jagged1 was not detected in controls, but was observed as a band at 170kD in response to treatment with 10ng/ml TGFβ1, as we have reported previously (John et al., 2002). Induction was confirmed using two independent antibodies (goat anti-Jagged1 shown). Although TGFβ1 is the most studied isoform, expression of TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 in the inflamed CNS has also been reported (De Groot et al., 1999; Lagord et al., 2002). Similar to TGFβ1, we found that both 10ng/ml TGFβ2 and -3 induced Jagged1 expression in primary human astrocytes (Fig. 1b). The effect of TGFβ isoforms was specific: none of the other cytokines/growth factors tested had any detectable effect on Jagged1, including IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, IFNγ, bFGF, VEGF-A, EGF, LIF, CNTF, IGF-1, PDGF-AA and -AB, and the TGF superfamily member activin-A (Fig. 1a). Previous work from our laboratory has also shown that induction of Jagged1 mRNA and protein by TGFβ1 is dose-dependent and blocked by the naturally-occurring latency-associated peptide (John et al., 2002).

TGFβ1 activates Smad-dependent and -independent signaling pathways in human astrocytes

TGFβ1 has been shown to activate Smad-dependent signaling and also the Smad-independent MAP kinase, PI3 kinase, and Rho GTPase signaling pathways (Shi and Massagué, 2003) (Fig. 1c). Using immunoblotting and confocal microscopy, we examined these events in primary human astrocytes and compared them to the timecourse of Jagged1 induction. Jagged1 was first observed at 90min and reached a plateau at 16h following TGFβ1 treatment (Fig. 1d). We found that TGFβ1 induced activation of Smad-dependent signaling and the p38, JNK and Erk MAP kinase and PI3 kinase pathways (Fig. 1d). Activation of Smad signaling, as assessed by phospho-Smad2 (Ser465/467), was observed as a 58kD band 30min after treatment of cultures with 10ng/ml TGFβ1, and decreased from 3h (Fig. 1d). Suggesting functionality, phosphorylated Smad2 localized to cell nuclei in TGFβ1-treated cultures (Fig. 1e, 60min illustrated). Phosphorylation of p38 at Thr180/Tyr182 followed a similar timecourse (Fig. 1d). Phospho-GSK3 (Ser21/9), a marker of PI3 kinase pathway activation, was first observed at 1.5h and remained stable through at least 16h (Fig. 1d). Activation of JNK (phosphorylation at Thr183/Tyr185) was delayed and transient relative to the other pathways tested, and was observed solely at 6h (Fig. 1d). Activation of the MAP kinase and PI3 kinase pathways in response to TGFβ1 was low compared to positive controls (astrocytes treated with IL-1β 30min or insulin 15min). We were unable to detect activation of the Rho GTPase pathway in TGFβ1-treated cultures using a rhotekin pulldown assay (data not shown). These studies show that in human astrocytes, TGFβ-mediated induction of Jagged1 is accompanied by activation of both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling pathways.

ALK5 blockade inhibits Jagged1 induction and Smad-dependent and -independent signaling

To determine the mechanism underlying Jagged1 induction, we used a combination of pharmacologic inhibitors (Figure 2) and siRNA (Figure 3). In inhibitor studies (outlined in Fig. 2a), human astrocyte cultures were pretreated with inhibitor for 2h, then activated with 10ng/ml TGFβ1. At times shown, treated cultures and controls were harvested and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Concentrations of antagonists used were based on previous findings in our and other laboratories (Laping et al., 2002; John et al., 2004), and their efficacy and specificity were confirmed by immunoblotting using phospho-specific antibodies as in Figure 1. At the concentrations used, none of these antagonists had significant effects on cell viability, as determined by LDH release and trypan blue exclusion (data not shown).

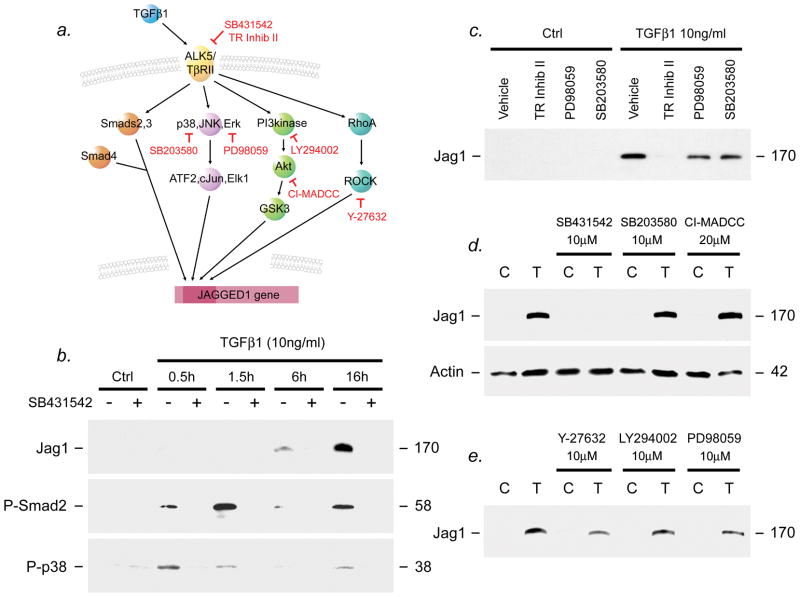

Figure 2. ALK5 blockade inhibits Jagged1 induction and Smad-dependent and -independent signaling.

Human astrocyte cultures were pretreated for 2h with inhibitors for the TGFβ serine/threonine receptor kinase ALK5 or for Smad-independent pathways (a), then activated with 10ng/ml TGFβ1 and harvested at times shown (b) or 24h (c-e). Efficacy and specificity were confirmed using phospho-specific antibodies shown in Figure 1 (data not shown). Inhibitors of ALK5 including SB431542 and TR Inhibitor II strongly downregulated TGFβ1-mediated induction of Jagged1 (b-d), and activation of both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling (b). In contrast, no effect was observed in response to treatment with inhibitors of Smad-independent signaling pathways, including MAP kinase pathway inhibitors SB203580 (p38, c), PD98059 (Erk, c), the PI3 kinase-Akt pathway inhibitors CI-MADCC (Akt, d) and LY294002 (PI3 kinase, e), or the Rho-ROCK pathway inhibitor Y-27632 (e). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments with each inhibitor in separate cultures.

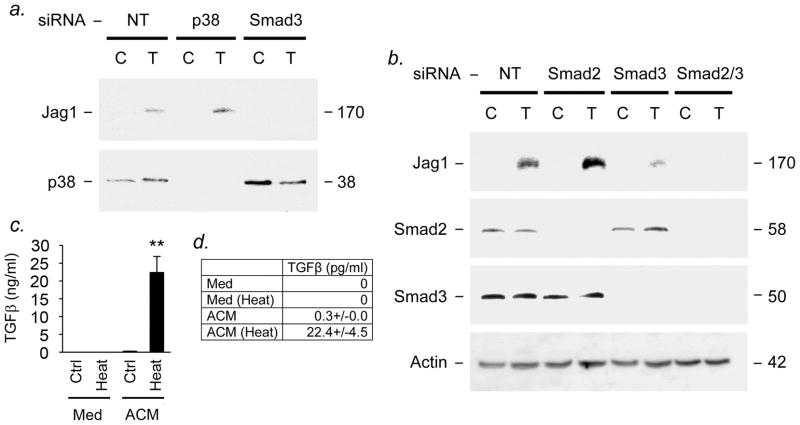

Figure 3. Inhibition of Smad3 restricts Jagged1 induction.

(a,b) Human astrocyte cultures were transfected with siRNA for components of Smad-dependent or -independent pathways, or nontargeting control siRNA, or sham control, then treated with 10ng/ml TGFβ1. At 24h, cultures were subjected to immunoblotting for Jagged1 and signaling molecules. (a) TGFβ1 induction of Jagged1 was inhibited in cultures transfected with Smad3 siRNA. In contrast, targeting of components of TGFβ1-activated Smad-independent pathways had no effect. (b) While siRNA for Smad3 downregulated Jagged1 induction, siRNA for Smad2 had no detectable effect when used alone. However, siRNA for Smad2 potentiated the effects of Smad3 siRNA on Jagged1 induction when used in combination. (c,d) To measure astrocytic production of active and latent TGFβ, astrocyte-conditioned medium was applied to a cell line stably expressing luciferase under the control of a TGFβ-sensitive portion of the PAI-1 promoter. To activate latent cytokine, media were pretreated at 80°C for 5min. Luciferase activity was measured at 16h. (c,d) The concentration of active TGFβ in astrocyte-conditioned medium was low (<0.3pg/ml). However, the total concentration of TGFβ in conditioned medium measured following heat activation was much higher (22.4ng/ml), and this difference was significant (c,d, **P<0.01, ANOVA plus Bonferroni post test). TGFβ was undetectable in control samples (non-conditioned medium, heat-treated or untreated). Thus, almost all of the TGFβ present in astrocyte-conditioned medium (98.7%) exists in the form of latent complexes which require activation prior to receptor binding. Data shown are representative of at least 3 independent experiments in separate cultures.

Initially, we examined the effects of TGFβ1 receptor antagonists. We found that inhibitors of the serine/threonine receptor kinase ALK5, including SB431542 and TGF Receptor Inhibitor II strongly downregulated TGFβ1-mediated induction of Jagged1 (Figs. 2b–d), as well as activation of both Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling pathways (Fig. 2b).

Inhibition of Smad-independent signaling has no effect on Jagged1 induction

In contrast to the effects of ALK5 inhibitors, treatment of cultures with inhibitors of the Smad-independent MAP kinase signaling pathways SB203580 (p38, Fig. 2c), PD98059 (Erk, Fig. 2c) and JNK Inhibitor II (not shown), had no detectable effect on Jagged1 induction. Inhibitors of the PI3 kinase-Akt pathway including CI-MADCC (Akt, Fig. 2d) or LY294002 (PI3 kinase, Fig. 2e) also had no detectable effect on Jagged1 expression, nor were effects effect observed using Rho-ROCK pathway inhibitors such as Y-27632 (Fig. 2e).

Inhibition of Smad3 restricts induction of Jagged1, and Smad2 siRNA potentiates this effect

To inhibit Smad-dependent signaling, we used siRNA to target individual Smads in primary cultures of human astrocytes (Figure 3). Cells were transfected with siRNA specific for components of Smad-dependent or -independent signaling pathways, or nontargeting control siRNA, or transfection reagent alone (sham control), then treated with 10ng/ml TGFβ1. At 24h, cultures were harvested and protein extracts subjected to immunoblotting for Jagged1 and targeted and nontargeted control signaling molecules. We found that TGFβ1-mediated induction of Jagged1 was downregulated in cultures transfected with Smad3 siRNA (Figs. 3a,b). In contrast, targeting of Smad-independent pathways, such as p38 MAP kinase, had no effect (Fig. 3a). Using longer film exposures, we were also able to isolate the contributions of different Smads to these events (Fig. 3b). Whereas siRNA for Smad3 downregulated Jagged1 induction, we found that siRNA for Smad2 had no detectable effect when used alone (Fig. 3b, upper panel), despite the fact that Smad2 was specifically downregulated by its targeted siRNA. However, siRNA for Smad2 potentiated the downregulatory effects of Smad3 siRNA on Jagged1 induction (Fig. 3b). Collectively, these data show that TGFβ1-mediated expression of Jagged1 occurs via activation of ALK5 and the transcription factor Smad3, and suggest a minor and nonessential role for Smad2. In contrast, our results downplay involvement of Smad-independent pathways.

TGFβ expressed by human astrocyte cultures exists as an inactive latent complex

Previous work has shown that astrocytes can be induced to express TGFβ isoforms, for example in CNS inflammation or injury (Lagord et al., 2002), and strong immunoreactivity for TGFβ1, -2 and -3 is found in hypertrophic astrocytes in acute MS lesions (De Groot et al., 1999). Human astrocytes have also been reported to express TGFβ2 and smaller amounts of TGFβ1 in vitro (De Groot et al., 1999). However, our data showed that induction of Jagged1 in astrocyte cultures required administration of exogenous TGFβ (see Figure 1). To understand why Jagged1 was inducible in but not constitutively expressed by human astrocytes in vitro, we used a bioassay to measure concentrations of active and latent TGFβ in astrocyte-conditioned medium (Figs. 3c,d). As a TGFβ reporter, this system uses a mink lung epithelial cell (MLEC) line stably expressing firefly luciferase under the control of a TGF-β–sensitive portion of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) promoter, and its specificity and sensitivity have been characterized previously (Abe et al., 1994).

Conditioned medium from primary human astrocyte cultures, or unconditioned control, were applied to MLEC cells expressing PAI-luc for 16h, then luciferase activity measured. In some cases media were pretreated at 80°C to activate latent cytokine, since TGFβ isoforms are initially secreted as high molecular weight complexes that must be activated prior to receptor binding (Abe et al., 1994). These studies showed that concentrations of active TGFβ in astrocyte-conditioned medium were low (<0.3pg/ml, Figs. 3c,d). However, the total concentration of TGFβ in conditioned medium as measured following heat activation was 75 times higher (22.4ng/ml), and this difference was significant (Figs. 3c,d, P<0.01, ANOVA plus Bonferroni post test). Concentrations in non-conditioned medium controls (heat-treated or untreated) were undetectable (Figs. 3c,d). Thus, these studies indicate that almost all of the TGFβ present in astrocyte-conditioned medium (98.7%) exists in the form of latent complexes, which only bind to TGF receptors following activation.

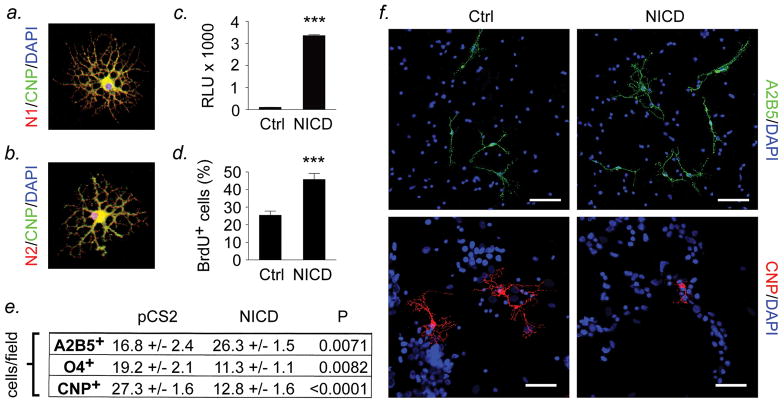

Notch1 activation is restrictive for rodent OPC differentiation and permissive for expansion

To determine how these events in the astrocyte might impact OPC proliferation and/or differentiation, we performed experiments using primary rodent and human cells (Figures 4,5). In initial studies, we examined the effects of activating Notch signaling in primary cultures of rat P1 cortical Ran2− A2B5+ OPCs (Figure 4). Immunofluorescence of cultures left to differentiate in growth factor-free medium for 5d demonstrated that Notch1 and Notch2 receptors were expressed by mature arborized CNPase+ oligodendrocytes (Figs. 4a,b) as well as by immature A2B5+ OPCs (data not shown), compatible with previous reports (Wang et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2009). To determine the consequences of activation of Notch signaling, we nucleofected OPCs with an expression construct for the Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD, gift of Dr. Rafael Kopan, Washington University) (Schroeter et al., 1998). NICD-nucleofected cells displayed potent activation of Notch signaling at 24h, as assessed by conucleofection of the Hes1 luciferase reporter pGa981-6 (Fig. 4c, P<0.001, Student’s t test) (Minoguchi et al., 1997). OPC cultures nucleofected with NICD or empty vector were left to differentiate for 5d, pulsed with 10μmol BrdU, then fixed and stained for differentiation markers and imaged by confocal microscopy. Numbers of cells positive for each marker were counted by a blinded observer in 5 fields at 20x magnification, and compared using statistics. These experiments showed that after differentiation for 5d, the phenotype of cells in NICD-nucleofected cultures was immature compared to controls (Figs. 4d–f). NICD-nucleofected cultures contained significantly greater numbers of bipolar A2B5+ OPCs than empty vector controls, and significantly fewer O4+ and mature CNPase+ oligodendrocytes (Figs. 4e,f, Student’s t test, P values shown). NICD-nucleofected cultures also contained larger numbers of BrdU+ proliferating cells than controls (Fig. 4d, P<0.001). These results demonstrate that activation of Notch signaling restricts OPC maturation and is permissive for proliferation. They are compatible with previous studies (Wang et al., 1998; Genoud et al., 2002) and our own recent work (Zhang et al., 2009).

Figure 4. Activation of Notch1 signaling restricts OPC differentiation and is permissive for expansion.

(a,b) Rat OPCs (Ran2− A2B5+) were purified from cerebral cortices at P1 by immunopanning, differentiated for 5d in growth factor-free medium, then immunostained for Notch1 and 2 and differentiation markers and imaged by confocal microscopy. Notch1 and Notch2 receptors were expressed by mature arborized CNPase+ oligodendrocytes (a,b) as well as by immature A2B5+ OPCs (data not shown). (c-f) To determine the consequences of activation of Notch signaling, OPCs were nucleofected with an expression construct for Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) or empty vector control. Activation of Notch signaling was confirmed at 24h in cultures conucleofected with NICD and the Hes1 luciferase reporter pGa981-6 (c, Student’s t test, ***P<0.001). (d-f) OPC cultures nucleofected with NICD or empty vector control were left to differentiate for 5d as above, pulsed with 10μmol, then fixed and stained for differentiation markers and imaged by confocal microscopy. NICD-nucleofected cultures contained significantly greater numbers of BrdU+ proliferating cells (d, Student’s t test, P<0.001) and immature A2B5+ OPCs (e,f, P=0.0071) than empty vector controls, and significantly fewer O4+ and mature CNPase+ oligodendrocytes (e,f, P values shown). Data illustrated are representative of 3 independent experiments in separate cultures. Scalebars, (a,b) 10μm, (f) 25μm.

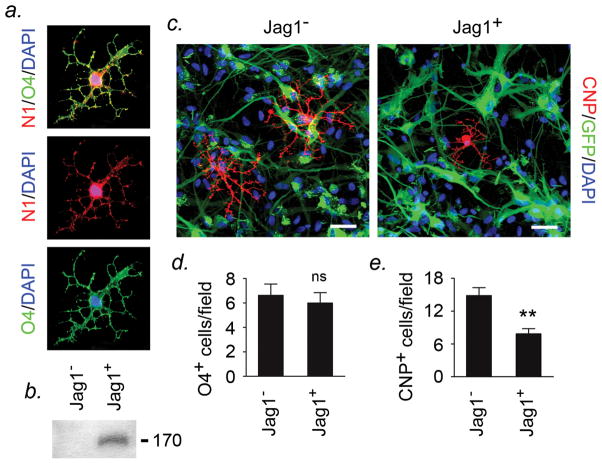

Figure 5. Jagged-Notch signaling restricts human OPC differentiation.

(a) Primary human oligodendrocyte-enriched cultures were established as described (Wilson et al., 2003) and differentiated for 5d in growth factor-free medium, then immunostained for Notch1 and differentiation markers and imaged by confocal microscopy. Notch1 localized to O4+ oligodendrocytes (a), as well as to A2B5+ OPCs, and arborized CNPase+ cells (not shown). (b-e) Astrocytes were cotransfected with a Jagged1 expression vector (pcDNA3hJag1) or empty vector control plus pEGFP for visualization, and stable lines established. Jagged1 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (b). (c-e) Primary human oligodendrocyte-enriched cultures were plated onto Jagged1-expressing astrocytes and empty vector controls and left to differentiate for 5d, then co-cultures fixed and differentiation analyzed as above. Although Jagged1-expressing and control co-cultures contained similar numbers of O4+ oligodendrocytes after 5d (d), significantly fewer mature arborized CNPase+ cells were present in Jagged1-expressing co-cultures than in controls, and this difference was significant (c,e, Student’s t test, P<0.01). Scale bars, (a) 5μm, (e) 10μm. Data are representative of findings from at least 3 experiments in separate cultures.

Jagged-Notch signaling restricts human OPC differentiation

To determine whether Jagged1 expressed by astrocytes regulates the differentiation of human OPCs, we used primary human astrocyte-oligodendrocyte co-cultures (Figure 5). Primary human oligodendrocyte-enriched cultures were established as previously described (Wilson et al., 2003). Immunofluorescence confirmed that Notch1 localized to O4+ oligodendrocytes (Fig. 5a), as well as to A2B5+ OPCs and arborized CNPase+ cells (not shown). Astrocyte cultures were established as above, then transfected with a Jagged1 expression vector (pcDNA3hJag1, gift of Dr. Linheng Li, Stower’s Research Institute) (Li et al., 1997) or empty vector control, and stable lines established. Jagged1 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5b), and for additional visualization of transfected cells, cultures were cotransfected with a GFP expression vector (pEGFP) in addition to pcDNA3hJag1 or empty vector control (Fig. 5c). Primary human oligodendrocyte-enriched cultures were then plated onto Jagged1-expressing astrocytes or empty vector controls and left to differentiate for 5d, then co-cultures were fixed and differentiation analyzed as above.

These studies revealed that the maturation of human oligodendrocytes was restricted in co-cultures containing Jagged1-expressing astrocytes. Although Jagged1-expressing and control co-cultures contained similar numbers of O4+ oligodendrocytes (Fig. 5d) and Olig2+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells (data not shown) after 5d, significantly fewer mature arborized CNPase+ oligodendrocytes were present in Jagged1-expressing co-cultures than in controls, and this difference was significant (Figs. 5c,e, P<0.01, Student’s t test). Thus, these data show that in human cultures, Jagged1-Notch1 signaling from astrocytes to oligodendrocytes is sufficient to restrict OPC differentiation. They are compatible with our recent findings (Zhang et al., 2009), and suggest functional relevance of astrocytic Jagged1 expression to regulation of progenitor differentiation.

Discussion

The extent of remyelination in an MS lesion is believed to depend upon the available number of oligodendrocyte progenitors and their successful recruitment and differentiation into myelin-forming cells (Gensert and Goldman, 1997). Incomplete remyelination may therefore be attributable to lack of progenitor numbers, failure of recruitment, or inability to complete the maturation and myelination programs (Gensert and Goldman, 1997; Wolswijk, 1998) For this reason, signaling pathways that control the balance between OPC proliferation and maturation are compelling candidates for research in the context of myelin repair within MS plaques. The Notch pathway is a candidate for investigation based on its regulation of myelin formation in development (Wang et al., 1998; Genoud et al., 2002; Stidworthy et al., 2004). Canonical Notch signaling is induced via binding of ligands including Jagged1-2 and Delta1-4 to Notch-1 and -2 receptors, leading to RBPJκ activation and induction of the bHLH transcription factors Hes1 and Hes5 (Louvi and Artavanis-Tsakonas, 2003; Kopan and Ilagan, 2009). Initial studies examining functional significance in vivo suggested that canonical Notch signaling is not a major rate-determining factor for remyelination (Stidworthy et al., 2004). However, we recently found that repair of acute demyelinating lesions is accelerated in young adult mice with Notch1 inactivation targeted throughout the oligodendrocyte lineage (Olig1Cre:Notch112f/12f) (Zhang et al., 2009). These results support a role for Notch1 as one of the pathways regulating the balance between differentiation and proliferation within the oligodendrocyte progenitor pool in adults, as well as during development. However, the source of the ligand driving these events has remained relatively unexplored.

The results of our previous work have implicated Jagged1 as driving Notch1 signaling in the inflamed CNS (John et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2009). Within and around active MS plaques, we detected expression of Jagged1 by hypertrophic astrocytes, but were unable to detect Delta1 (John et al., 2002). Significantly, we also found Notch1 and Hes5 expression localizing to the same areas, in NG2+ PDGFRα+ OPCs. Moreover, we recently detected Jagged1 expression by GFAP+ astrocytes in demyelinating lesions in mice subjected to lysolecithin-induced demyelination, but again did not detect Delta1 in these samples (Zhang et al., 2009). Jagged1 expression was low or absent in normal white matter, although it is known to be expressed in germinitive areas of telencephalon including the subventricular zone (Nyfeler et al., 2005). In parallel studies in vitro, using microarray surveys of human astrocytes we observed induction of Jagged1 by the inflammatory cytokine TGFβ1 (John et al., 2002). In contrast, we did not detect induction of Delta1 or other Notch ligands by TGFβ1 or other cytokines or growth factors in these cultures.

Here, we have examined induction of Jagged1 by TGFβ1 in human astrocytes, and the consequences of Jagged1-Notch1 signaling between human astrocytes and OPCs. The results of these experiments reveal the mechanism underlying TGFβ-mediated induction of Jagged1 (Figures 1–3). We found induction of Jagged1 by TGFβ1 to be specific (Figure 1), and mediated via the receptor kinase ALK5 (Figure 2) and the transcription factor Smad3 (Figure 3). In contrast, the role of Smad2 appeared minor and nonessential (Figure 3). Our findings suggest that the effects of TGFβ isoforms on Jagged1 are mediated entirely via Smad-dependent signaling (Figures 2,3). Interestingly, we also found that although human astrocytes express TGFβ in vitro, almost all of it in astrocyte-conditioned medium is in the form of latent complexes that require activation prior to receptor binding, hence induction of Jagged1 requires administration of exogenous active cytokine (Figure 3). Collectively, these data define the signaling pathways involved in induction of Jagged1 by TGFβ, and represent new findings that add to our understanding of these events.

Our results also provide support for the hypothesis that expression of Jagged1 by human astrocytes restricts maturation of human OPCs (Figures 4,5), a theme that we and others have explored previously (John et al., 2002; Stidworthy et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2009). In functional studies, activation of Notch signaling using an expression construct for NICD in rodent OPCs inhibited their differentiation and was permissive for expansion, confirming that Notch regulates the balance between proliferation and maturation within the progenitor pool (Figure 4). We also examined the consequences of Jagged1-Notch1 signaling in co-cultures of primary human astrocytes and human OPCs, and found that astrocytes expressing Jagged1 restricted oligodendrocyte differentiation (Figure 5). Collectively, these data suggest that TGFβ1-induced activation of Jagged1-Notch1 signaling may impact the size and differentiation state of the OPC pool in the postnatal human CNS (Figure 6). These findings are compatible with our previous work, and further support the concept that expression of Notch ligands by reactive glia may regulate the behavior of OPCs in the human CNS.

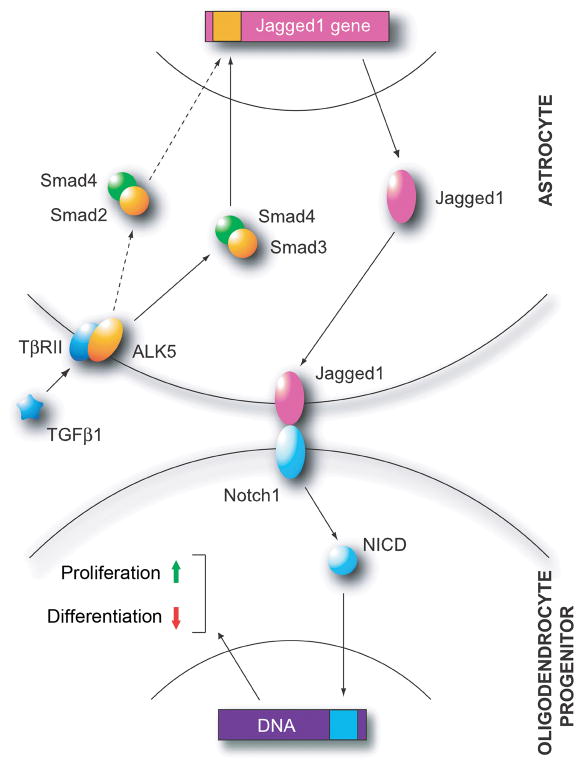

Figure 6. Proposed model for activation of the Jagged/Notch/Hes pathway in MS lesions.

TGFβ1 (left) binds to its receptor (TβRII) on astrocytes in active MS lesions, activating the serine/threonine receptor kinase ALK5. This leads to phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Smads 2 and 3 as heterodimers with Smad4, and Jagged1 gene transcription. Jagged1 expressed at the surface of reactive astrocytes binds to Notch1 receptors on OPCs (below), leading to S3 cleavage of Notch1 and nuclear translocation of NICD. Activation of Notch1 signaling alters the balance between OPC proliferation and differentiation. Under the influence of canonical Notch signaling, expansion of the progenitor pool is favored, at the expense of differentiation and myelin formation.

Our data showing that TGFβ1 induction of Jagged1 is Smad3-dependent (Figure 3) are of particular interest on account of the different mechanisms used by Smad3/4 versus Smad2/4 complexes to accomplish DNA binding. TGFβ1 induces serin/threonine phosphorylation of the R-Smads-2 and -3, formation of heterodimers with the co-Smad, Smad4, and nuclear translocation (Shi and Massagué, 2003). Within the nucleus, Smad3/4 binds directly to consensus DNA-binding elements in promoters of target genes, but conversely Smad2/4 heteromers are targeted to DNA via interaction with transcription factors containing a Smad interaction motif (SIM) (Moustakas et al., 2001). Thus, Smad3-dependent signaling occurs via a direct mechanism, while Smad2 uses a more indirect approach. Our results suggest that, in the case of TGFβ1-mediated induction of Jagged1, the signaling mechanism that uses direct DNA binding is dominant.

Our observation that the Notch pathway has an inbuilt sensitivity to inflammatory insult mediated via induction of Jagged1 in astrocytes is of interest in the context of basic neurobiology in addition to its translational relevance. Our finding indicates a point of intersection between TGFβ and Notch signaling, two pathways believed to be critical regulators of early metazoan development (Jessell and Sanes, 2000). While interactions between the two pathways have been reported previously, this has been primarily at the level of their transcription factors (Blokzijl et al., 2003). Our data support the hypothesis that the two signaling pathways are linked and interact, in development and postnatally. Interestingly, induction of Jagged1 by TGFβ1 has recently been demonstrated in kidney and in joints in addition to the CNS (Zavadil et al., 2004; Spagnoli et al., 2007), thus this mechanism appears conserved across organs.

The results of the current study and our recent work using Olig1Cre:Notch112f/12f mice suggest that Jagged1-Notch1 signaling may represent a potential means for manipulating oligodendrocyte progenitor proliferation versus differentiation in the adult CNS. In demyelinating diseases such as MS, lesion repair is often incomplete particularly as the course enters its chronic stages (Trapp et al., 1998; Chang et al., 2000). In early MS, oligodendrocyte progenitors are believed to be present in considerable numbers in at least some lesions, and the extent of remyelination may be limited by their recruitment or differentiation (Scolding et al., 1998). Conversely, later in the disease course, OPC number may act as a limiting factor (Chang et al., 2000). Differential manipulation of Notch signaling may provide a potential avenue to regulate these parameters within the progenitor pool, to expand progenitor numbers in chronic plaques (activation of signaling), and for subsequent differentiation of progenitors into myelin-forming cells in both acute and chronic lesions (pathway inhibition).

Strategies for tissue protection and successful lesion repair represent a challenging area in current research into MS. In order to design effective strategies for potentiating remyelination, it is important to understand mechanisms that govern the size and maturation state of the progenitor population, and the ligands driving these effects. Our data suggest that Notch1 signaling represents a mechanism regulating oligodendrocyte progenitor proliferation and differentiation in adults, and that this pathway has an inbuilt sensitivity to injury and/or inflammation. We propose that in patients with inflammatory demyelinating disease, TGFβ1-triggered Jagged1-Notch1 interactions may represent one of the pathways regulating the size and differentiation of the oligodendrocyte progenitor pool.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bradford Poulos, Director of the Human Fetal Tissue Repository at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, for tissue collection, and the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Microscopy Shared Resource Facility. Supported by USPHS Grants NS046620 and NS056074 and ARRA Administrative Supplement NS056074-02S1 (GRJ), and by National Multiple Sclerosis Society Postdoctoral Fellowship FG1739 (YZ) and Research Grants RG3874 (GRJ) and RG3827-A5 (CFB), and by the Jayne and Harvey Beker Foundation (GRJ). The MSSM-Microscopy Shared Resource Facility is supported by funding from NIH-NCI grant R24 CA095823.

References

- Abe M, Harpel JG, Metz CN, Nunes I, Loskutoff DJ, Rifkin DB. An assay for transforming growth factor-beta using cells transfected with a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter-luciferase construct. Anal Biochem. 1994;216:276–84. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokzijl A, Dahlqvist C, Reissmann E, Falk A, Moliner A, Lendahl U, Ibáñez CF. Cross-talk between the Notch and TGF-beta signaling pathways mediated by interaction of the Notch intracellular domain with Smad3. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:723–728. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brück W, Stadelmann C. The spectrum of multiple sclerosis: new lessons from pathology. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:221–224. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000169736.60922.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso GL, Chao MV. Telomerase and oligodendrocyte differentiation. J Neurobiol. 2001;49:224–234. doi: 10.1002/neu.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Nishiyama A, Peterson J, Prineas J, Trapp BD. NG2-positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6404–6412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06404.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancy SP, Baranzini SE, Zhao C, Yuk DI, Irvine KA, Kaing S, Sanai N, Franklin RJ, Rowitch DH. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1571–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.1806309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genoud S, Lappe-Siefke C, Goebbels S, Radtke F, Aguet M, Scherer SS, Suter U, Nave KA, Mantei N. Notch1 control of oligodendrocyte differentiation in the spinal cord. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:709–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensert JM, Goldman JE. Endogenous progenitors remyelinate demyelinated axons in the adult CNS. Neuron. 1997;19:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinks GL, Franklin JM. Distinctive patterns of PDGF-A, FGF-2, IGF-1, and TGF-β1 gene expressing during remyelination of experimentally-induced spinal cord demyelination. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:153–168. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell TM, Sanes JR. Development. The decade of the developing brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Shankar SL, Shafit-Zagardo B, Massimi A, Lee SC, Raine CS, Brosnan CF. Multiple sclerosis: re-expression of a developmental pathway that restricts oligodendrocyte maturation. Nat Med. 2002;8:1115–1121. doi: 10.1038/nm781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John GR, Chen LF, Rivieccio MA, Melendez-Vasquez CV, Hartley A, Brosnan CF. Interleukin-1β induces a reactive astroglial phenotype via deactivation of the Rho GTPase-Rock axis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2837–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4789-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagord C, Berry M, Logan A. Expression of TGFβ2 but not TGFβ1 correlates with the deposition of scar tissue in the lesioned spinal cord. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:69–82. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laping NJ, Grygielko E, Mathur A, Butter S, Bomberger J, Tweed C, Martin W, Fornwald J, Lehr R, Harling J, Gaster L, Callahan JF, Olson BA. Inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1-induced extracellular matrix with a novel inhibitor of the TGF-beta type I receptor kinase activity: SB-431542. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:58–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Krantz ID, Deng Y, Genin A, Banta AB, Collins CC, Qi M, Trask BJ, Kuo WL, Cochran J, Costa T, Pierpont ME, Rand EB, Piccoli DA, Hood L, Spinner NB. Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat Genet. 1997;16:243–251. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvi A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signaling in vertebrate neural development. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:93–102. doi: 10.1038/nrn1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RH, Dinsio K, Wang R, Geertman R, Maier CE, Hall AK. Patterning of spinal cord oligodendrocyte development by dorsally derived BMP4. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:9–19. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoguchi S, Taniguchi Y, Kato H, Okazaki T, Strobl LJ, Zimber-Strobl U, Bornkamm GW, Honjo T. RBP-L, a transcription factor related to RBP-Jkappa. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2679–2687. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Souchelnytskyi S, Heldin CH. Smad regulation in TGF-beta signal transduction. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4359–69. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyfeler Y, Kirch RD, Mantei N, Leone DP, Radtke F, Suter U, Taylor V. Jagged1 signals in the postnatal subventricular zone are required for neural stem cell self-renewal. EMBO J. 2005;24:3504–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine CS. Demyelinating diseases. In: Davis RL, Robertson DM, editors. Textbook of Neuropathology. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1997. pp. 243–287. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-inducedproteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N, Franklin R, Stevens S, Heldin CH, Compston A, Newcombe J. Oligodendrocyte progenitors are present in the normal adult human CNS and in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1998;121:2221–2228. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert T, Bauer J, Weissert R, Fazekas F, Storch MK. Notch1 and its ligand Jagged1 are present in remyelination in a T-cell- and antibody-mediated model of inflammatory demyelination. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Blakemore WF, McDonald WI. Central remyelination restores secure conduction. Nature. 1979;280:395–396. doi: 10.1038/280395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnoli A, O’Rear L, Chandler RL, Granero-Molto F, Mortlock DP, Gorska AE, Weis JA, Longobardi L, Chytil A, Shimer K, Moses HL. TGF-beta signaling is essential for joint morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:1105–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stidworthy MF, Genoud S, Li WW, Leone DP, Mantei N, Suter U, Franklin RJ. Notch1 and Jagged1 are expressed after CNS demyelination, but are not a major rate-determining factor during remyelination. Brain. 2004;127:1928–1941. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mörk S, Bö L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson HC, Onischke C, Raine CS. Human oligodendrocyte precursor cells in vitro: phenotypic analysis and differential response to growth factors. Glia. 2003;44:153–165. doi: 10.1002/glia.10280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolswijk G. Chronic stage multiple sclerosis lesions contain a relatively quiescent population of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. J Neurosci. 2998;18:601–609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00601.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Sdrulla AD, diSibio G, Bush G, Nofziger D, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Barres BA. Notch receptor activation inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron. 1998;21:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Miller RH, Ransohoff RM, Robinson S, Bu J, Nishiyama A. Elevated levels of the chemokine GRO-1 correlate with elevated oligodendrocyte progenitor proliferation in the jimpy mutant. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2609–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02609.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavadil J, Cermak L, Soto-Nieves N, Böttinger EP. Integration of TGF-beta/Smad and Jagged1/Notch signalling in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. EMBO J. 2004;23:1155–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Taveggia C, Melendez-Vasquez C, Einheber S, Raine CS, Salzer JL, Brosnan CF, John GR. Interleukin-11 potentiates oligodendrocyte survival and maturation, and myelin formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12174–12185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2289-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Argaw AT, Gurfein BT, Zameer A, Snyder BJ, Ge C, Lu QR, Rowitch DH, Raine CS, Brosnan CF, John GR. Notch1 signaling plays a role in regulating precursor differentiation during CNS remyelination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19162–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902834106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]