Abstract

The rational design of immunoprotective hydrogel barriers for transplanting insulin-producing cells requires an understanding of protein diffusion within the hydrogel network and how alterations to the network structure affect protein diffusion. Hydrogels of varying crosslinking density were formed via the chain polymerization of dimethacrylated PEG macromers of varying molecular weight, and the diffusion of six model proteins with molecular weights ranging from 5,700 to 67,000 g/mol was observed in these hydrogel networks. Protein release profiles were used to estimate diffusion coefficients for each protein/gel system that exhibited Fickian diffusion. Diffusion coefficients were on the order of 10−6 to 10−7 cm2/s, such that protein diffusion time scales (td = L2/D) from 0.5 mm thick gels vary from 5 minutes to 24 hours. Adult murine islets were encapsulated in PEG hydrogels of varying crosslinking density, and islet survival and insulin release was maintained after two weeks of culture in each gel condition. While the total insulin released during a one hour glucose stimulation period was the same from islets in each sample, increasing hydrogel crosslinking density contributed to delays in insulin release from hydrogel samples within the one hour stimulation period.

Keywords: crosslinking density, diffusion, encapsulation, hydrogel, islet

Introduction

Many cell and tissue replacement therapies are limited by the lack of appropriate delivery vehicles for cells and engineered tissues. Specifically, the regeneration or replacement of insulin-producing cells in patients with type 1 diabetes presents a unique challenge. Strategies for successfully transplanting adult islets or undifferentiated islet precursor cells are dependent upon the synthesis of a controlled transplantation environment that promotes cell survival, function, and, when appropriate, differentiation, while protecting transplanted cells from immune mediated destruction. Biocompatible, synthetic hydrogels present a promising platform for designing clinically relevant insulin-producing cell carriers with three-dimensional structures capable of supporting entrapped cell morphology and with tunable network structures for controlling the diffusion of molecules to and from entrapped cells (1–3). Because the permeability of many synthetic hydrogels is readily altered, these systems have been extensively studied for the delivery of cells with specific secretory functions (4, 5), including pancreatic islets (6–8). The necessity to understand and control diffusion in hydrogels designed for these applications is clear. For the delivery of adult islets and islet precursor cells alike, the importance of transport regulation extends beyond relatively low molecular weight insulin and high molecular weight immune cell secreted antibodies to many other proteins of intermediate size such as growth factors critical to cell survival or differentiation and remains independent of the micro- or macroencapsulation design.

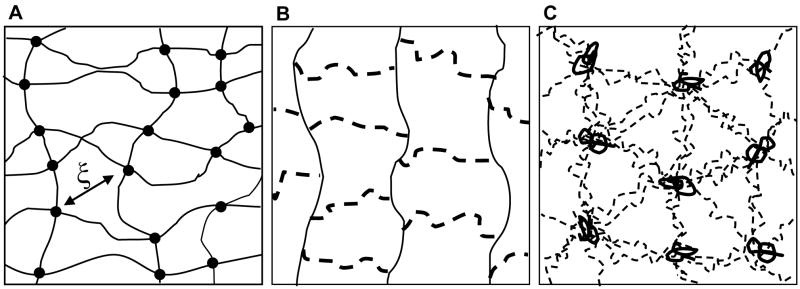

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) hydrogels formed via the photoinitiated polymerization of multifunctional macromolecules have shown promise for islet encapsulation, specifically with respect to in vitro biocompatibility (8). The ability to readily alter PEG network properties to influence the diffusion of a limited number of proteins has been demonstrated (6). However, a complete understanding of solute diffusion within PEG hydrogels requires an improved understanding of the gel network structure. Recent studies have demonstrated that PEG gels formed from the chain polymerization of functional macromers are not adequately described by classical hydrogel theories. The classic depiction of hydrogel network structure includes linear polymer chains connected by crosslinking points, occupying no volume, as shown in Figure 1A (9). The average mesh size of the network (ξ) is thus dependent on the length of the polymer chains between crosslinks and is used to calculate and predict solute diffusivity in the gel (10). In contrast, crosslinks within networks formed from the homopolymerization of high molecular weight divinyl macromers, such as dimethacrylated PEG, are not adequately described as single points. During polymerization, radicals propagate through the carbon-carbon double bonds of the methacrylate end groups to form polymethacrylate kinetic chains, and the crosslinks in this network are linear PEG molecules extending from each repeat unit of the kinetic chain to those of additional chains. In an ideal network, crosslinking density is low, and crosslinking molecules have negligible dimensions. However, the homopolymerization of divinyl macromers leads to networks with relatively high crosslinking densities, and crosslinking molecules substantially contribute to the structure and chemistry of the network. The addition of a crosslink dimension further complicates the concept of network mesh size. The idealized view of gels formed from dimethacrylated PEG macromers (Figure 1B) attempts to account for the crosslink dimension within the classical hydrogel depiction, representing these networks as homogeneous distributions of PEG crosslinks and polymethacrylate kinetic chains. However, the relative hydrophobicity of the polymethacrylate kinetic chains compared to the hydrophilicity of the PEG crosslink chains likely leads to the formation of complex structures in aqueous solution. Recent reports have proposed a PEG network structure composed of randomly coiled polymethacrylate chains with emanating, extended PEG chains (Figure 1C) (11, 12). This proposed network structure is supported by small angle neutron scattering (SANS) characterization of chain polymerized PEG hydrogels and their respective precursor solutions (13). In this description of gel structure, a gel mesh size defined by the distance between crosslinks is replaced by a characteristic length that represents the distance between polymethacrylate core chains (12).

Figure 1.

Simplified hydrogel structures. (A) Classic hydrogel depiction with linear polymer chains and point crosslinks. (B) Idealized network formed from divinyl macromers with linear PEG crosslinks (dashed) connecting kinetic chains (solid). (C) Proposed network structure of polymerized dimethacrylated PEG with linear PEG crosslinks (dashed) and hydrophobic polymethacrylate core molecules (solid). (Adapted from reference #8).

Because of the inability of classical theories to accurately capture the structure of PEG gels and the paucity of data related to diffusion measurements in PEG gels, this work used an experimental approach to systematically investigate the diffusion of model proteins in gels formed from the chain polymerization of PEG macromers. The release of proteins of varying molecular weight (5,700 to 67,000 g/mol) from PEG gels formed via the photopolymerization of varying molecular weight PEG macromers (2,000 to 10,000 g/mol) was followed experimentally to provide insight into the diffusion of molecules with biological relevance in the application of these gels for insulin-producing cell delivery. These results also provide valuable experimental information for future efforts to develop theoretical relationships that more accurately describe solute diffusion in hydrogel structures formed via chain polymerization of macromolecular monomers. Finally, isolated murine islets were encapsulated in PEG networks formed from varying molecular weight macromers to investigate any direct effects of hydrogel formation or crosslinking density on encapsulated islet survival and the time scale and rate of insulin secretion in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Macromer synthesis and hydrogel formation

Poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDM) was synthesized by reacting linear PEG (M̄n = 2000, 4000, 6000, 8000, and 10000 g/mol) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with methacrylic anhydride (Sigma) at a molar ratio of 1:10 via microwave irradiation under solvent free conditions as previously described (11). Macromer product was collected by precipitation into chilled (4°C) ethyl ether (Sigma) and vacuum filtration, and macromer purification was achieved by dialysis in deionized water (diH2O) using cellulose ester dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cutoff of 1000 g/mol (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA). Purified PEGDM was collected by lyophilization and stored at 4°C under nitrogen. Percent methacrylation was determined using 1H NMR by comparing the area under the integrals for the vinyl resonances (δ = 5.7 ppm, δ = 6.1 ppm) to that for the PEG backbone (methylene protons, δ = 4.4 ppm). Percent methacrylation for all macromers was approximately 95 ± 5%.

Hydrogels were formed from a precursor solution of 10 wt % PEGDM in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, Gibco) and 0.025 wt % of the photoinitiator 2-hydroxy-1-[4-(hydroxyethoxy)phenyl]-2-methyl-1-propanone (Ciba-Geigy, Basel, Switzerland) exposed to 365 nm ultraviolet light at an intensity of ~7 mW cm−2 for 10 minutes. For protein release experiments, disc-shaped hydrogels were formed with a diameter of 10 mm and thickness of 0.4 mm to achieve a high diameter to thickness ratio (~25) and allow for the approximation of one-dimensional diffusion in the z-direction by assuming radial diffusion to be negligible. Hydrogel samples were swollen in PBS at 37°C for 24 hours and weighed to obtain the equilibrium swollen mass, Ms. Samples were then placed in deionized water to remove PBS salts, frozen, and lyophilized overnight, and the dry polymer mass, Md, determined. The volumetric swelling ratio, Q, was calculated from the mass swelling ratio, (Ms/Md), using density conversion factors (2), and the theoretical concentration of crosslinkable double bonds in the hydrogel precursor solution (mol/L) was used as a measure of hydrogel crosslinking density.

2.2 Protein release measurement

Hydrogels were incubated in 1 mg/ml protein solutions for 24 hours at 4°C for uniform loading of the following proteins: insulin, myoglobin, trypsin inhibitor, carbonic anhydrase, ovalbumin, and bovine serum albumin (Sigma). For protein diffusion coefficients on the order of 10−6 to 10−8 cm2/s, the time scale for loading into 0.4 mm thick gels ranges from 5 minutes to 12 hours. Therefore, 24 hour incubation times should be sufficient to achieve equilibrium protein concentrations within the gels. The diffusion time scales observed in similar studies of various model proteins through even denser polymer networks further support the rationale for a 24 hour loading time period (6, 14). For protein release, loaded gels were placed in PBS at 37°C and transferred to fresh solutions after 6, 12, 30, 60, and 90 minutes to maintain near sink conditions, and the amount of protein released into each solution was measured with the MicroBCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Standard solutions of each protein were prepared immediately prior to gel loading and maintained in the same conditions as those used for gel loading and protein release until assay measurements were collected.

2.3 Estimation of protein diffusion coefficients from measured release profiles

To determine the diffusion coefficients of each protein with respect to changes in the hydrogel crosslinking density, the measured protein release profiles were fitted to the following solution for diffusion through a sheet with uniform initial concentration and equal surface concentrations:

| (1) |

Here, Mt is the amount of solute that has diffused out of the sheet at some time t; M∞ is the amount after time equals infinity; l is the sheet thickness; and D is the diffusion coefficient of the given solute within the sheet (15). This solution assumes solute diffusion follows Fick’s second law, and comparisons between experimental release profiles and those predicted by this solution were made to comment on Fickian versus non-Fickian protein diffusion within the PEG hydrogels.

2.4 Islet isolation, culture, and encapsulation

Islets from adult Balb/c mice were obtained from the Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center at the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes (Denver, CO). Briefly, after digestion of pancreatic tissue with collagenase, islets were isolated by density gradient purification and hand picked under a microscope. Isolated islets were cultured in RMPI 1640 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco), and 0.5 μg/mL fungizone (Gibco) at 37°C in humid conditions with 5% CO2. For each macroencapsulation sample, approximately 20 islets were suspended in 30 μl of hydrogel precursor solution prior to photopolymerization and entrapped throughout the resulting hydrogel disc upon gel network formation. Swollen, islet-containing hydrogels were approximately 4 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness with individual islets scattered throughout.

2.5 Islet viability and insulin release

A membrane integrity assay, LIVE/DEAD®, from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR) was used to evaluate cell viability. Encapsulated islets were placed in the LIVE/DEAD® staining solution for 10 minutes at 37°C. After staining, live cells fluoresced green, and dead cells fluoresced red. Stained samples were visualized within the three-dimensional hydrogel environment using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Quantification of LIVE/DEAD® staining results is difficult in these samples, because clear delineations between individual live, stained cells are rare. However, when few dead cells are observed, stained islet viability can be estimated by comparing the number of dead cells to an approximate number of live cells based on the islet area within the fluorescent image (i.e., 100 cells per 100 μm2). Previous studies employed LIVE/DEAD® staining in observing encapsulated islet viability, because this technique does not require the destruction of the surrounding encapsulation barrier as common metabolic activity assays such as the MTT assay would (8, 16, 17).

Insulin secretion was evaluated by exposure of encapsulated islets to static glucose stimulation for one hour on specified days following hydrogel formation. Encapsulation samples were first placed in 1 ml of low glucose concentration solution (1.1 mM) for 45 minutes, followed by incubation in 1 ml of high glucose concentration buffer (16.7 mM) for one hour. The insulin concentration in the high glucose buffer solutions after one hour was measured by a mouse/rat insulin ELISA (Mercodia, Winston Salem, NC). The CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to measure the ATP content of each encapsulation sample. Islet-containing hydrogel samples were incubated in 0.5 ml culture media combined with 0.5 ml CellTiter-Glo reagent for 30 minutes on an orbital shaker (~200 rpm). The luminescence of each sample solution was measured using a microplate reader (Perkin Elmer Wallac Victor2, 1420 Multilabel Counter), and the insulin released from each sample was normalized by the ATP content of the respective sample to account for insulin secretion disparities between samples due to variations in the number of encapsulated cells.

For observation of insulin release within a one hour high glucose (16.7 mM) incubation period, samples were transferred to fresh high glucose solutions (250 μl each) at 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minute time points within the one hour static stimulation period. The insulin content of each solution was measured by ELISA, and cumulative insulin secretion was plotted as a percentage of the total amount secreted from islets in hydrogels formed from each molecular weight macromer.

3. Results

3.1 PEG gel properties as a function of initial macromer structure

PEG hydrogels with varying crosslinking densities were synthesized using 10 wt % solutions of dimethacrylated PEG macromers formed from linear PEG polymers of different molecular weights (2,000 to 10,000 g/mol). The volumetric equilibrium swelling ratio and the concentration of crosslinkable double bonds, a measure of crosslinking density, for the resulting PEG gels are presented in Table 1. Both properties strongly impact solute diffusivity within the hydrogel network.

Table 1. PEG hydrogel properties.

Properties of PEG gels formed from the solution polymerization of varying molecular weight macromers, including the volumetric swelling ratio (Q) at 37°C and the theoretical concentration of crosslinkable double bonds in the hydrogel precursor solution (mol/L) relative to the number average molecular weight (M̄n ) of the PEG core in the macromolecular monomer.

| M̄n, g/mol | Volumetric Swelling Ratio, Q | x-linkable double bonds(mol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0500 |

| 4000 | 12.3 ± 0.7 | 0.0250 |

| 6000 | 15.3 ± 0.9 | 0.0167 |

| 8000 | 17.8 ± 0.4 | 0.0125 |

| 10000 | 20.9 ± 0.9 | 0.0100 |

3.2 Protein diffusion in PEG gels

The release of proteins of varying molecular weight from PEG hydrogels was experimentally observed. Table 2 lists each protein studied with its corresponding molecular weight, literature reported hydrodynamic radius, and diffusion coefficient in aqueous solution at 37°C as calculated by the Stokes-Einstein equation:

| (2) |

Table 2. Released protein properties.

Proteins released from PEG gels and their corresponding structural properties (12) and diffusion coefficients in aqueous solution at 37°C as calculated by the Stokes-Einstein equation (13).

| Protein | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Hydrodynamic Radius (nm) | Diffusion Coefficient (cm2/s × 106) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin | 5700 | 1.47 | 2.16 |

| Myoglobin | 17000 | 2.12 | 1.50 |

| Trypsin Inhibitor | 20000 | 2.19 | 1.45 |

| Carbonic Anhydrase | 29000 | 2.35 | 1.35 |

| Ovalbumin | 43000 | 2.98 | 1.07 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | 67000 | 3.56 | 0.89 |

Here, Do is the diffusion coefficient of the solute in a given solution; k is Boltzman’s constant (1.38 × 10−23 J/K); T is temperature (37°C = 310 K); η is the viscosity of the solvent (6.915 × 10-4 N•m/s2 for water at 37°C (18)); and Rs is the radius of the solute (20). Diffusion coefficients calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation were used as rough approximations for comparison with experimentally derived diffusion coefficients for proteins in hydrogels of varying crosslinking density.

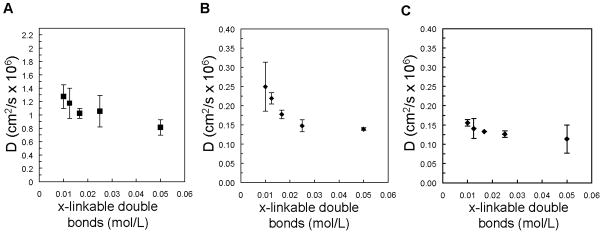

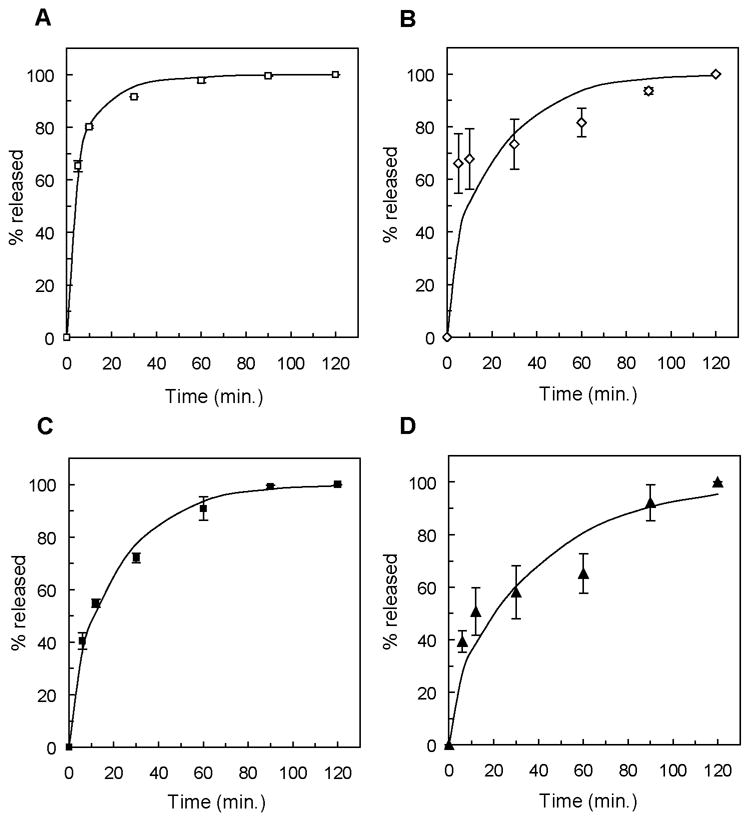

Individual proteins were loaded at 1 mg/ml into PEG hydrogels formed from varying molecular weight macromers, and protein release was experimentally measured as described. Diffusion coefficients for each protein in each PEG hydrogel system were estimated by fitting the release data to the one-dimensional Fickian diffusion model, given in Equation 1. Agreement between the experimentally measured release profiles and the theoretically predicted release profiles plotted in Figure 2 suggests that insulin, trypsin inhibitor, and carbonic anhydrase exhibit Fickian diffusion through hydrogels formed from the 10,000 g/mol PEG macromer. Experimental and theoretical release profiles for these proteins from all other PEG gels were also in agreement.

Figure 2.

Release profiles of insulin (A), trypsin inhibitor (B), and carbonic anhydrase (C) from PEG gels formed from the polymerization of macromers derived from 10,000 g/mol PEG. Experimental data are presented as individual data points, and the solid lines represent the theoretical Fickian release profiles.

The release of ovalbumin from PEG gels formed from the 10,000 g/mol macromer followed Fickian diffusion (Figure 3A), but ovalbumin release from PEG gels with greater crosslinking densities did not agree with theoretically predicted profiles (3B). This inconsistency was also observed in the release of myoglobin, with Fickian diffusion apparent in PEG gels formed from macromers of molecular weight 6,000 g/mol and greater (Figure 3C), but poor agreement between experimental and theoretical release profiles in gels formed from 2,000 g/mol and 4,000 g/mol macromer (Figure 3D). Further analysis of protein diffusion in PEG gels was limited to protein/gel combinations that exhibited Fickian diffusion, allowing for the use of diffusion coefficients estimated by fitting release profiles to Equation 1.

Figure 3.

Protein release profiles of ovalbumin from gels formed from the 10,000 g/mol (A) and 8,000 g/mol PEG macromers (B) and myoglobin from gels formed from 10,000 g/mol (C) and 2,000 g/mol PEG macromers (D). Experimentally measured release data is shown as individual data points, and the theoretical release profiles are represented as solid lines.

Hydrogel samples incubated in a 1 mg/ml solution of bovine serum albumin did not release detectable concentration of protein suggesting that bovine serum albumin does not significantly penetrate these networks. Even if the diffusion coefficient of bovine serum albumin within the PEG gels was reduced by two orders of magnitude (0.8 × 10−9 cm2/s) relative to that in aqueous solution, protein loading of the gels should occur in approximately 12 hours. Although complete protein release would not be achieved in 2 hours, release of bovine serum albumin near the gel surface would be observed. For proteins that diffused from PEG gels in agreement with Fickian diffusion profiles, the calculated diffusion coefficients were plotted with respect to the concentration of crosslinkable double bonds in the hydrogel precursor solution (Figure 4). In comparison to the approximate diffusion coefficient in solution predicted by the Stokes-Einstein equation, insulin diffusivity is reduced by approximately 40% in the PEG gels with the lowest crosslinkable bond concentration and up to 60% in PEG gels with the highest concentration (Figure 4A). The diffusion coefficients of larger proteins, such as trypsin inhibitor and carbonic anhydrase, were decreased to approximately 10% of that in aqueous solution (Figure 4B and 4C). The following equation for the diffusion coefficient of a given solute through a gel network (Dg) relative to that of the solute in solution (Do) demonstrates how diffusion is dependent on the solute radius (rs) relative to a crosslinked network characteristic length (ξ) and the equilibrium water content of the hydrogel network, described here as the polymer volume fraction in the gel (ν2):

| (3) |

Figure 4.

Calculated diffusion coefficients, D, for insulin (A), trypsin inhibitor (B), and carbonic anhydrase (C) as a function of the concentration of crosslinkable double bonds in the hydrogel precursor solution.

Y is the ratio of the critical volume required for a successful translational movement of the solute to the average free volume per liquid molecule and is usually approximated to be 1 (21). ν2 is simply the inverse of the equilibrium swelling ratio (Q) presented in Table 1.

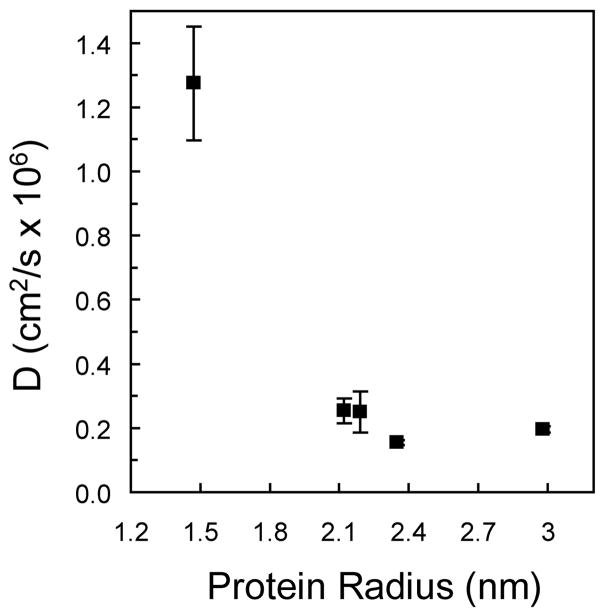

Additionally, the diffusion coefficients of each protein in PEG gels formed from the 10,000 g/mol macromer were plotted relative to reported protein radii in solution (Figure 5). Insulin, with a radius of 1.47 nm, has the largest diffusion coefficient, and all other proteins, with radii greater than 2.0 nm, have significantly lower diffusion coefficients. The corresponding approximate time scale for insulin diffusion from the 0.4 mm thick PEG gels is 5 minutes, relative to 30 and 45 minutes for trypsin inhibitor and carbonic anhydrase, respectively.

Figure 5.

Calculated diffusion coefficients, D, of proteins in PEG gels formed from the 10,000 g/mol PEG macromer as a function of the protein hydrodynamic radius.

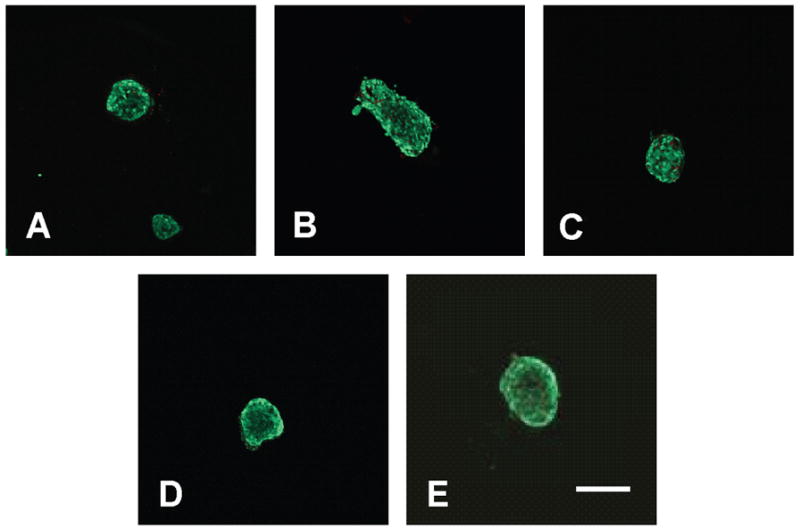

3.3 Islet viability in PEG gels of varying crosslinking density

Islet survival in PEG gels formed from varying macromer molecular weight was observed by LIVE/DEAD® staining after 14 days in culture. Encapsulated islets retained greater than 97% viability in all PEG gel conditions at this time point (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Islet viability in gels formed from PEG-based macromers with molecular weights of 2,000 g/mol (A), 4,000 g/mol (B), 6,000 g/mol (C), 8,000 g/mol (D), and 10,000 g/mol (E) after 14 days in culture. Live cells stained green, and dead cells stained red. Scale bar represents 200 μm.

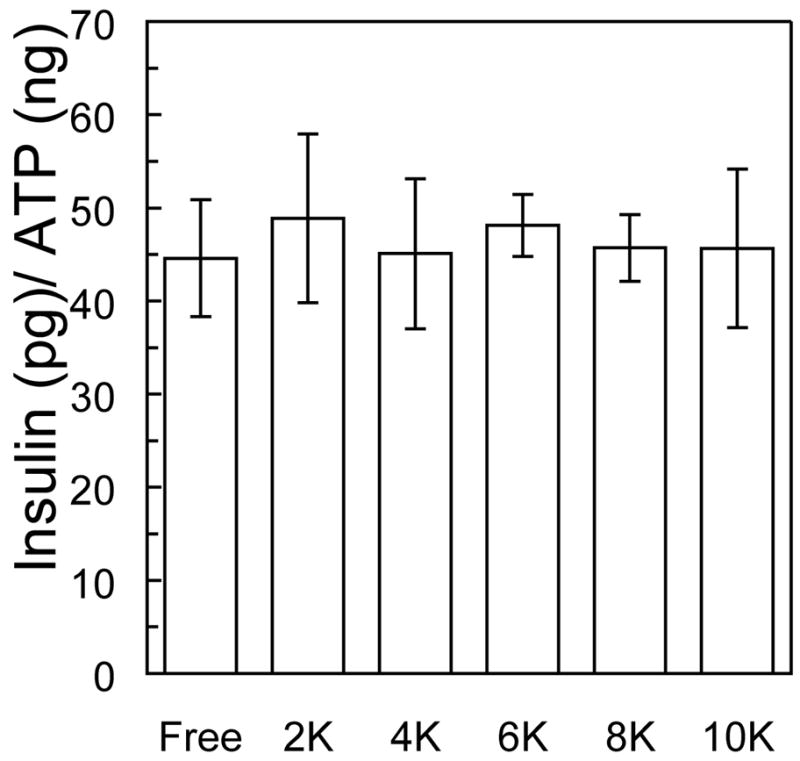

3.4 Islet function in PEG gels of varying crosslink density

Total insulin release from islets encapsulated in PEG gels formed from each macromer molecular weight was measured following one hour static glucose challenge after one week in culture and normalized by sample ATP content to avoid sample variation due to different cell numbers between samples. Islet insulin release from within all PEG gel samples was similar to that released by unencapsulated islets (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Insulin released during a one hour glucose stimulation (16.7 mM) from islets encapsulated in PEG gels formed from varying molecular weight macromers after 14 days in culture.

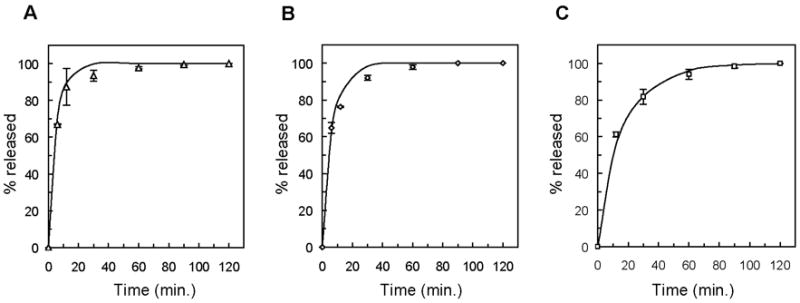

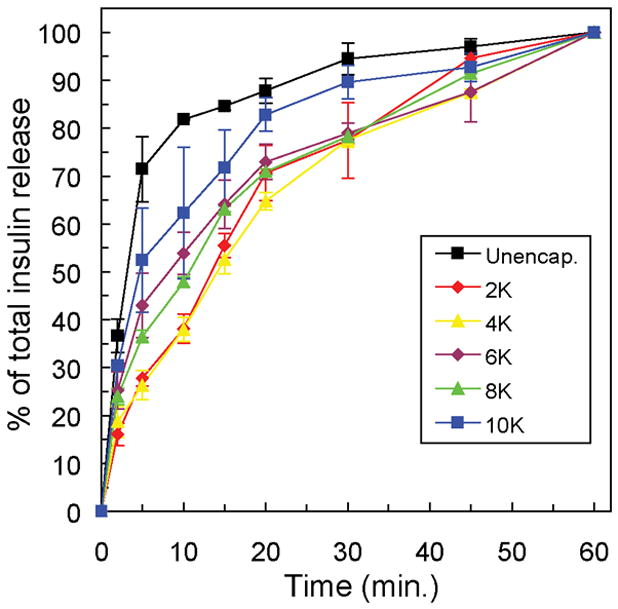

To investigate any delays in islet response to high glucose stimulation introduced by the PEG gel structure, encapsulated islet samples were transferred to fresh glucose solutions repeatedly during the one hour glucose stimulation period. The insulin content of solutions collected after 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, and 60 minutes of glucose stimulation was measured and presented cumulatively over 60 minutes as a percentage of the total insulin released (Figure 8). Approximately 70% of the total insulin secreted is measured in the first five minutes of stimulation from unencapsulated islets. This value is reduced to 50% in islet samples encapsulated in PEG gels with the lowest crosslinking density, and further reduced with increasing crosslinking density. While islets in each PEG gel condition secreted similar total amounts of insulin (40–50 pg/ng ATP, Figure 7), insulin release to the solution surrounding encapsulated samples was delayed by the diffusion of insulin through the PEG gel. Considering the diffusion coefficient of insulin in the PEG gels with the lowest crosslinking density (~1.27 × 10−6 cm2/s), if an islet were positioned at the center of the hydrogel, the time scale for the diffusion of secreted insulin to the surrounding solution would be approximately 30 minutes. However, in these samples, islets were distributed throughout the gels, and only insulin secreted by islets positioned in the exact center of the gel were subject to the longest diffusion pathway of 0.5 mm. The observed insulin response delays were shorter than 30 minutes, because many encapsulated islets were located nearer to the hydrogel surface.

Figure 8.

Insulin release from islets encapsulated in PEG gels formed from varying molecular weight macromers measured at intervals with the one hour stimulation in high glucose (16.7 mM) solution. Insulin release at each time point is presented as a percentage of the total released over one hour (~45 pg/ng ATP).

4. Discussion

Early efforts to design hydrogels for adult islet encapsulation and transplantation largely focused on optimizing the immunoprotective barrier properties, and hydrogel systems that did not significantly hinder diffusion of small proteins, specifically insulin, to and from encapsulated cells but blocked the passage of large immune-cell secreted products such as antibodies. The concept of a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO), or a molecular size that cannot penetrate the network, was widely explored. However, relative to proteins which are monodisperse, the polymers used to synthesize encapsulation barriers are polydisperse, further complicating the concept of a gel MWCO and contributing to very broad MWCO ranges. Alginate-poly-L-Lysine capsules have been synthesized with a MWCO between 14,500 g/mol and 44,000 g/mol, as determined by measuring the diffusion of linear dextran molecules and model proteins (22). Other natural and synthetic polymer membrane studies have targeted a MWCO of 50,000 g/mol (23–28).

Even if the ideal encapsulation barrier were achieved, the in vivo environment for transplanted cells would still present harsh conditions for survival and function (29). In addition to an immediate foreign body inflammatory response to the transplanted graft and the islet-specific autoimmune rejection introduced by the type 1 diabetic immune system, the presence of the encapsulation barrier, no matter how thin, prevents revascularization within the islet mass, thus eliminating the original, physiological source for islet nutrient supply and the primary avenue for blood glucose regulation. Few studies have focused on the diffusion of proteins with sizes in between the extremes of insulin and IgG that may also be critical for successful insulin-producing cell transplantation. With a molecular weight of approximately 38,000 g/mol, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is one example of a protein that may influence encapsulated islet survival. Under hypoxic stress, islets secrete elevated levels of VEGF to promote localized vascularization (30, 31), and for encapsulated islets, the growth of blood vessels near the hydrogel surface may be of critical importance in establishing the proximity to the host circulation required for continued islet survival and function. Another growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), has also been shown to promote transplanted islet viability and function (32). With an approximate molecular weight of 60,000 g/mol, transport of HGF to encapsulated islets will require a barrier with a MWCO greater than 50,000 g/mol and a PEG gel with a crosslinking density less than those synthesized in this work. The diffusion of various growth factors is equally important in the use of three-dimensional hydrogel environments for transplanting islet progenitor cells. Whether exogenously delivered or locally secreted by host tissues, factors necessary for guiding the differentiation and function of these cells must diffuse through the hydrogel barrier (33, 34).

In contrast, while the exclusion of high molecular weight proteins, such as antibodies (~150,000 g/mol) would provide protection from many cytotoxic immune molecules, other potentially toxic proteins such as IL-1β, with an approximate molecular weight of 17,500 g/mol, could easily penetrate the encapsulation barrier (35). The limitations of semipermeable membranes for immunoprotection have been reviewed (36), and an encapsulation barrier that could actively modulate the local immune response in addition to excluding many large toxic molecules may one day be beneficial to the preservation of encapsulated islet survival (37).

In the presented experiments, the diffusion of model proteins with molecular sizes between those typically studied was investigated in PEG hydrogels with network structures not accurately described by classical theories. Alterations in PEG gel crosslinking density resulted in changes in the amount of free volume available for diffusion within the gel, directly influencing protein diffusion within these gels. If the gel structure serves only to sterically interfere with protein diffusion, the gel can be regarded as a property of the solution, and the protein concentration gradient between the gel and the surrounding solution remains the primary driving force for diffusion, resulting in Fickian diffusion profiles. Not all of the proteins released in these experiments exhibited this type of diffusion in every PEG gel, indicating that other potential interactions are influencing diffusion. Complicating factors that may contribute to non-Fickian diffusion include changes in protein conformation, and therefore shape, during the release experiment, possible aggregation of protein molecules during the release experiment, and interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, between entrapped proteins and the PEG network. While significant adsorption of proteins to the hydrophilic PEG gels is unlikely, as the solute dimensions approach those that characterize the hydrogel network, diffusion is further complicated as solute contact with the gel structure is increased and even low specificity, low strength interactions such as van der Waals forces may affect solute diffusion.

The use of varying molecular weight PEG macromers not only resulted in hydrogels of varying crosslinking density, but also changes to the polymerization solution, specifically radical concentration profiles in time. Free radical concentration is influenced by not only the concentration of crosslinkable double bonds, but also factors such as solution viscosity and diffusion limitations introduced by gel network formation (2). For the PEG hydrogels tested, changes in the polymerization solution and the final crosslinking density did not affect encapsulated islet survival or alter islet insulin secretion over a one hour glucose stimulation period. At specific time points within the one hour high glucose incubation, however, insulin secretion was delayed from islets entrapped in 1 mm thick PEG gels relative to unencapsulated islet insulin release. The trend of increasing delays with increasing PEG crosslinking density suggests that diffusion of insulin through the gel network plays a role in the response time of encapsulated islets to changes in external glucose concentration. This diffusion-related delay could be offset by reducing the thickness of the gel barrier, and thus the distance between encapsulated islets and the surrounding environment. Given that total insulin release over the 1 hour incubation was not diminished with encapsulation, further tests of islet function are necessary to determine if the observed delays will be problematic for the ultimate goal of reversing hyperglycemia through implantation of islet-gel constructs.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Science Foundation and the Department of Education’s Graduate Assistantships in Areas of Nation Need Program for fellowships to LMW, the National Institute of Health/Howard Hughes Medical Institute Scholars Program for funding to CGL, and the National Science Foundation (Grant #EEC044771) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute for research funding.

References

- 1.Hoffman AS. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant SJ, Anseth KS. Photopolymerization of Hydrogel Scaffolds. In: Ma PX, Elisseeff J, editors. Scaffolding in Tissue Engineering. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin CC, Metters AT. Hydrogels in controlled release formulations: Network design and mathematical modeling. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1379–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahooti S, Sefton MV. Effect of an immobilization matrix and capsule membrane permeability on the viability of encapsulated HEK cells. Biomaterials. 2000;21(10):987–995. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallbacka JJ, Nobrega JN, Sefton MV. Tissue engineering as a platform for controlled release of therapeutic agents: implantation of microencapsulated dopamine producing cells in the brains of rats. J Control Release. 2001;72:93–100. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruise GM, Scharp DS, Hubbell JA. Characterization of permeability and network structure of interfacially photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1287–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li RH. Materials for immunoisolated cell transplantation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998;33:87–109. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber LM, He J, Bradley B, Haskins K, Anseth KS. PEG-based hydrogels as an in vitro encapsulation platform for testing controlled β-cell microenvironments. Acta Biomaterialia. 2006;2:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flory PJ, Rehner R. Statistical mechanics of crosslinked polymer networks. I. Rubberlike elasticity. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1943;11:512. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peppas NA, Barr-Howell BD. Characterization of the cross-linked structure of hydrogels. In: Peppas NA, editor. Hydrogels in Medicine and Pharmacy. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1986. pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin-Gibson S, Bencherif S, Cooper JA, Wetzel SJ, Antonucci JM, Vogel BM, Horkay F, Washburn N. Synthesis and characterization of PEG dimethacrylates and their hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1280–1287. doi: 10.1021/bm0498777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watkins AW. Ph.D. Thesis. Ch 7. University of Colorado; 2006. Controlling and characterizing molecular distributions in hydrogels for biomaterials applications; pp. 176–188. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin-Gibson S, Jones RL, Washburn N, Horkay F. Structure-property relationships of photopolymerizable poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate hydrogels. Macromolecules. 2005;38:2897–2902. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourke SL, Al-Khalili M, Briggs T, Michniak B, Kohn J, Poole-Warren LA. A photo-crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel growth factor release vehicle for wound healing applications. AAPS PharmSci. 2003;5(33):1–11. doi: 10.1208/ps050433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crank J. The mathematics of diffusion. New York: Oxford Science Publications; 1975. pp. 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Risbud MV, Bhargava S, Bhonde RR. In vivo biocompatibility evaluation of cellulose macrocapsules for islet immunoisolation: Implications of low molecular weight cut-off. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:86–92. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui W, Barr G, Faucher KM, Sun XL, Safley SA, Weber CJ, Chaikof EL. A membrane-mimetic barrier for islet encapsulation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:1206–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geankoplis CJ. Transport processes and unit operations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR; 1993. p. 855. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbloom AJ, Nie S, Ke Y, Devaty RP, Choyke WJ. Columnar morphology of porous silicon carbide as a protein-permeable membrane for biosensors and other applications. Mat Sci Forum. 2006;527–529:751–574. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cussler EL. Diffusion –Mass transfer in fluid systems. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lustig SR, Peppas NA. Solute diffusion in swollen membranes .9. scaling laws for solute diffusion in gels. J Applied Polymer Science. 1988;36:735–747. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robitaille R, Leblond FA, Bourgeois Y, Henley N, Loignon M, Halle JP. Studies on small (<350 mm) alginate-poly-L-lysine microcapsules. V. Determination of carbohydrate and protein permeation through microcapsules by reverse-size exclusion chromatography. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:420–427. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(20000605)50:3<420::aid-jbm17>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zekorn T, Siebers U, Bretzel RG, Renardy M, Planck H, Zschocke P, Federlin K. Protection of islets of Langerhans from interleukin-1 toxicity by artificial membranes. Transplantation. 1990;50:391–400. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole DR, Waterfall M, McIntyre M, Baird JD. Microencapsulated islet grafts in the BB/E rat: a possible role for cytokines in graft failure. Diabetologia. 1992;35:231–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00400922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulseng B, Thu B, Espevik T, Skjak-Braek G. Alginate polylysine microcapsules as immune barrier: permeability of cytokines and immunoglobulins over the capsule membrane. Cell Transplant. 1997;6:387–394. doi: 10.1177/096368979700600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shamlou S, Kennedy JP, Levy RP. Amphiphilic networks. X. Diffusion of glucose and insulin (and nondiffusion of albumin) through amphiphilic membranes. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;35:157–163. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199705)35:2<157::aid-jbm3>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider S, Feilen PJ, Slotty V, Kampfner D, Preuss S, Berger S, Beyer J, Pommersheim R. Multilayer capsules: a promising microencapsulation system for transplantation of pancreatic islets. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1961–1970. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurian P, Kasibhatla B, Daum J, Burns CA, Moosa M, Rosenthal KS, Kennedy JP. Synthesis, permeability, and biocompatibility of tricomponent membranes containing polyethylene glycol, polydimethylsiloxane, and polypentamethylcycolpentasiloxane domains. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3493–3503. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davalli AM, Scaglia L, Zangen DH, Hollister J, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Vulnerability of islets in the immediate posttransplantation period: dynamic changes in structure and function. Diabetes. 1996;45:1161–1167. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.9.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorden DL, Mandriota SJ, Montesano R, Orci L, Pepper MS. Vascular endothelial growth factor is increased in devascularized rat islets of Langerhans in vitro. Transplantation. 1997;63:436–443. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199702150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vasir B, Jonas JC, Steil GM, Hollister-Lock J, Hasenkamp W, Sharma A, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Gene expression of VEGF and its receptors Flk-1/KDR and Flt-1 in cultured and transplanted rat islets. Transplantation. 2001;71:924–935. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiaschi-Taesch N, Stewart AF, Garcia-Ocana A. Improving islet transplantation by gene delivery of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and its downstream target, protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;48(2–3):191–199. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. New sources of pancreatic beta-cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:857–861. doi: 10.1038/nbt1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gangaram-Panday SJ, Faas MM, de Vos P. Toward stem-cell therapy in the endocrine pancreas. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babensee JE, Anderson JM, McIntire LV, Mikos AG. Host response to tissue engineered devices. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998;33:111–139. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(98)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray DWR. An overview of the immune system with specific reference to membrane encapsulation and islet transplantation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;944:226–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung CY, Anseth KS. Synthesis of immunoisolation barriers that provide localized immunosuppression for encapsulated pancreatic islets. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2006;17:1036–1042. doi: 10.1021/bc060023o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]