Abstract

Current national guidelines recommend that all HIV care providers routinely counsel their HIV-infected patients about reducing HIV transmission behaviors. In this article we identify the challenges and lessons learned from implementing a provider-delivered HIV transmission risk-reduction intervention for HIV-infected patients (Positive Steps). Based on a multi-site Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiative, we integrated the Positive Steps program into an infectious diseases clinic in North Carolina. Of the nearly 1200 HIV-infected patients, 59% were African American, 44% were white, 33% were women, and over 50% were between 25 and 44 years of age. We obtained feedback from a community advisory board, input from clinic staff, and conducted formative interviews with clinic patients and providers to achieve overall acceptance of the program within the clinic. Clinic providers underwent training to deliver standardized prevention counseling. During program implementation we conducted a quality assessment of program components, including reviewing whether patients were screened for HIV transmission risk behaviors and whether providers counseled their patients. Once Positive Steps was implemented, on average, 69% of patients were screened and 77% of screened patients were counseled during the first 12 months. In analyses of quarterly exit surveys of patients after their medical exams, on average, 73% of respondents reported being asked about safer sex and 51% reported having safer-sex discussions with their providers across six quarterly periods. Of those who had discussions, 91% reported that those discussions were “very” or “moderately helpful.” Providers reported time and competing medical priorities as barriers for discussing prevention with patients, however, provider-delivered counseling was routinely performed for 12 months. Overall, the findings indicate that the Positive Steps program was successfully integrated in an infectious diseases clinic and received well by patients.

Introduction

There were an estimated 56,300 new HIV infections in the United States in 2006.1 In North Carolina alone, the number of new HIV diagnoses rose annually from 1480 to 2073 between 1998 and 2003, an increase of 40%.2 In 2001, following an investigation into continued HIV transmission in the United States, (“No Time to Lose: Getting More from HIV Prevention”), the Institute of Medicine (IOM) reported that prevention interventions targeting persons diagnosed with HIV infection were urgently needed to reduce HIV transmission.3 The IOM report hypothesized that HIV medical care settings are highly feasible places for delivering interventions to a large number of HIV-positive persons.

In 2003, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the National Institutes of Health issued joint Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) guidelines for incorporating HIV prevention activities into routine HIV care. Key recommendations from the guidelines were the following: (1) structural approaches to the delivery of prevention messages; (2) routine screening of HIV transmission behaviors; (3) routine provider-delivered HIV prevention counseling; and (4) referrals to a prevention specialist for more intensive counseling and other social services as needed.4

Some studies have described the organizational barriers, such as long waiting times, insurance problems, and personal factors such as poor mental health, substance abuse, as challenges in retaining HIV-infected participants in care. When these missed opportunities in HIV care settings occur, HIV care providers may find it challenging to deliver prevention counseling, especially when primary medical issues are not consistently being met.5–8 Although some of these studies7,8 have described aspects of interventions that enhance and inhibit prevention and engagement in medical care, few studies have described the actual processes of implementing a provider-delivered HIV prevention counseling program. Furthermore, fewer still have provided data on the extent to which such an HIV prevention program was actually delivered to patients and how patients perceived the program.9

Recent studies suggest that clinic-based HIV prevention programs must target the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of both providers and patients, as well as address administrative and economic barriers.10,11 Organizational theories, such as Lewin's model of organizational change, can help guide the implementation of a new prevention program.10,12–15 Lewin's model describes organizational change as occurring in three stages: (1) “unfreezing” past behavior and attitudes by dealing with organizational resistance; (2) moving away from the status quo through exposure to new information and attitudes; and (3) reinforcing and maintaining the support for change in the organization.15

From 2004 to 2006, we participated in a multi-site project, funded by the CDC, to design, implement, and evaluate a clinic-based HIV prevention program consistent with the MMWR guidelines. The program, Positive Steps (Striving to Engage People), was implemented in seven HIV clinics including an academic infectious disease clinic in North Carolina. Principles from organizational change theories such Lewin's 3-Stage Model guided the integration of the Positive Steps program into the existing clinical practice at our site. For the study we collected measures of the implementation process from providers and patients to examine how closely providers followed the Positive Steps protocol and how patients received the program. Specifically, we sought to answer three questions: (1) What was the process by which the Positive Steps program was integrated into an academic infectious diseases clinic? (2) How often were HIV transmission risk screening and provider counseling delivered to patients during routine HIV care? (3) How did providers and patients respond to the integration of the program in the clinic?

Methods

The Positive Steps Program

With input from investigators at our and six other participating clinics (Nashville, Tennessee; Denver, Colorado; Kansas City, Missouri; Brooklyn, New York; and two clinics in Atlanta, Georgia), CDC investigators and staff from the Mountain Plains AIDS Education and Training Center (AETC), we designed the content of the Positive Steps program, the materials used in conducting and evaluating the program, and the manner in which the program was implemented at the clinics.16 The Positive Steps program included four key elements from the MMWR guidelines that were implemented at all seven sites. Specifically, we report here on how the four elements of the MMWR guidelines were implemented at a site in North Carolina.4

Structural approaches: Prevention messages in posters and brochures. Posters expressing such messages as “Protect yourself, don't make your HIV worse—Take Positive Steps” and “Protect others, don't pass your HIV around—Take Positive Steps.” were displayed in the clinic. Brochures that included similar prevention messages as well as risk-reduction strategies were available in the exam rooms.

Routine risk screener. A one-page, standardized risk screener with nine questions about sexual activity and substance use was given to HIV-positive patients by a nurse at each routine clinic visit to complete before the physician encounter. The screener included questions about recent sexual intercourse (yes versus no), numbers of sex partners, and the gender and type of the partners (primary versus casual). The completed risk screener was placed in the patient's medical chart before the patient was seen by the primary care provider to prompt the provider to discuss HIV prevention. Providers attempted to discuss HIV prevention with all HIV-positive patients at least quarterly.

Routine provider-delivered prevention messages and behavioral counseling. At each clinic, providers underwent a 4-hour group training session prior to implementing the counseling intervention and also received a booster training session 1 month into the intervention. The training sessions (facilitated by an infectious diseases physician and doctoral-level prevention specialist from the Mountain Plains AETC) included activities to: enhance communication skills; practice conducting brief prevention counseling and communication of prevention messages; and provide referrals when needed.16 As part of their prevention counseling activities, HIV care providers were instructed to review patients' responses to the risk screeners and provide counseling at each routine medical visit. The risk screener included a list of potential risk-reduction strategies providers could choose to discuss with patients and a place to document the amount of time they spent discussing prevention.

Referral resources. Two clinic social workers were available to accept referrals by providers for specialized prevention counseling as well as other services. These social workers attended all trainings with other clinic staff and also participated in a 3-day HIV prevention training with the North Carolina Division of Public Health on HIV counseling, testing, and partner notification services.

Patient characteristics at the North Carolina infectious disease clinic

Twelve hundred HIV-infected patients (59% African American, 44% white, 4% Hispanic, 1% Native American, and 2% other) were seen annually in this North Carolina infectious disease clinic during the time of program implementation and evaluation.17 Approximately a third of the patients at the clinic were women, and over half the population were between 25 and 44 years of age. Mode of HIV transmission was reported as heterosexual sex (47%), men who had sex with men (35%), and injection drug use (11%); the remaining 7% included mother-to-child transmission and unknown reasons.18 Current or past history of mental health and substance use disorders (primarily alcohol and crack cocaine use) were common, involving between 70%–80% of the clinic population.17 Over half of the patients traveled more than 50 miles to attend the clinic.

Steps taken to integrate the Positive Steps program into the clinic routine

Formative interviews with providers and patients

To inform the integration of prevention counseling into routine HIV care at our clinic, we conducted formative research (with funding through HRSA's Special Projects of National Significance). Standardized, semi-structured interviews were carried out with 19 HIV care providers (11 attending physicians, 4 fellow trainees, 3 nurse practitioners, and 1 physician assistant) and 20 patients living with HIV between February and April of 2004 (methods and main findings are published elsewhere).7 The provider interview guide included questions about their attitudes toward prevention, the prevention needs of their HIV-infected patients, and their experiences in providing prevention counseling to HIV-infected patients. The patient interview guide included questions regarding prevention needs as well as barriers and facilitators to practicing safer sex. Interviews were audiorecorded, transcribed, and coded using grounded theory to identify themes. Interviews were analyzed using QSR-N6 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) and ATLAS.ti 5.0 qualitative software (Berlin, Germany).

Meetings with stakeholders

We consulted with the clinic's community advisory board (CAB) in North Carolina, which consists of clinic patients and advocates; they were solicited for review and feedback about program procedures and materials. Additionally, for the purpose of the Positive Steps program, meetings were held between the clinic medical director and local health department officials (who conduct partner notification in North Carolina) to discuss violations of the North Carolina HIV control measures (e.g., withholding HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners, not using condoms during sexual intercourse) in the context of North Carolina public health reporting laws that require attending physicians to report patients who are violating the control measures.7 Providers anticipated conflicts between jeopardizing their patient–provider relationship by reporting patients who placed others at risk versus legal jeopardy to themselves if they did not report. This potential conflict was reconciled through these discussions. As a consequence, providers counseled patients without reporting if, in the providers' judgment, harm reduction could be achieved with a provider intervention during the Positive Steps program. To obtain and maintain support and participation in the Positive Steps program from administrative and clinical staff, meetings and in-service trainings were held, with the support of the Division Chief and Clinic Director. In these meetings, participants discussed potential changes to the clinic “flow” and new duties and responsibilities that would need to be fulfilled to have a successful prevention program.

Chart audits: risk screener

We performed regular audits of the risk screeners approximately quarterly (from October 2004 to October 2005) to assess whether or not: (1) patients received and completed the risk screener questions; and (2) providers performed prevention counseling. We conducted chart audits for the first two consecutive months after Positive Steps implementation to assess the initial uptake of the program, and performed audits approximately quarterly thereafter. We also assessed the median amount of time at months 4 and 9 after Positive Steps implementation that providers spent discussing prevention with patients, and the number of referrals they made for prevention issues or partner notification.

Quarterly patient visit exit surveys

Anonymous self-administered visit exit surveys were offered quarterly to all HIV-positive patients attending the clinic. The surveys were conducted during one week each quarter between January 2005 and April 2006 (project months 3–18). The exit survey items assessed patients' perceptions of screening and counseling activities. Patients were surveyed about whether or not the following prevention activities had occurred: (1) their primary care provider or someone else (nurse or social worker) had asked them about safer sex; (2) their primary care provider discussed safer-sex practices with them; (3) their primary care provider asked them about injection drug use (IDU) practices; and (4) their primary care provider discussed safer IDU practices with them. The survey also included items about whether patients felt that the discussions about safer-sex practices or injection drug use practices were helpful (4-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “very helpful”).

Post-implementation feedback and interviews with providers

Twelve months after the intervention was implemented, Positive Steps project staff (i.e., principal investigator, evaluator, and project director) met with providers to assess their perceptions of the successes and difficulties of the Positive Steps program. In addition to a semi-structured interview guide was used to interview 11 of the 19 providers previously interviewed during the formative phase (7 attending physicians, 1 fellow, 2 nurse practitioners, and 1 physician's assistant). Eight were not interviewed because they had either changed jobs or were out of the country for work-related reasons. For the post-implementation interviews providers were asked again about the prevention needs of their HIV-infected patients, their attitudes toward prevention, and their experiences in providing prevention counseling to HIV-infected patients. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and coded using grounded theory and ATLAS.ti 5.0 qualitative analysis software to identify themes.

Post-implementation discussions about risk screening tool

Fourteen months after the intervention was implemented, Positive Steps project staff had formal and informal meetings with providers and patients, respectively to discuss improvements to and sustainability of the risk screening tool.

Results

Question 1: What was the process by which the Positive Steps program was integrated into an academic infectious diseases clinic?

Meetings with stakeholders and providers

In pre-implementation meetings, CAB members expressed support for the initiation of a provider-delivered prevention program. Recognizing that implementing such a program would require a shift in the clinic culture, the CAB members suggested that the clinic inform clinic patients about the Positive Steps program in advance of its implementation. The CAB members also stressed the importance of not prolonging clinic visits as a result of prevention counseling. In addition, the CAB recommended making the risk screener and counseling brief, routine, and nonjudgmental. Although the multi-site Positive Steps team tried to make the risk screener minimally invasive, some CAB members in North Carolina expressed concern that the risk screener would be burdensome for patients because of the frequency of its administration (at each routine visit, approximately every 3–4 months) and the private nature of its questions. Because the Positive Steps program was intended to be delivered and evaluated in a standardized manner across seven sites, we did not modify the frequency of the risk screener or its content during the evaluation.

The Chief of the Infectious Diseases Division required all staff in the clinic to undergo the CDC-sponsored prevention counseling training and regularly placed the prevention project on the agenda of infectious disease division meetings and conferences. The Positive Steps trainings were attended by HIV care providers, clinic nurses, and clinic social workers.

We also held stakeholder meetings with clinic staff prior to Positive Steps implementation to provide them with information about the program and to give staff multiple opportunities to offer input into program implementation. For example, clinic staff decided to have the nurses administer the risk screener to patients during triage and place the risk screener in patients' charts for providers to review before clinical encounters. The clinic directors asked patients to arrive early for each appointment so that the brief (1–3 minute) risk screener could be completed without delaying appointments.

Formative interviews with providers and patients

During formative (pre-implementation) interviews, 19 medical care providers expressed their views about how program components should be implemented. From these interviews, we learned that it was important for staff to be able to refer complicated prevention cases to a social worker or prevention specialist in the clinic. The medical providers also requested that the following topics be included in prevention training: strategies for dealing with patients typically seen at their clinic (especially those who were poor, rural, African-American, or abused crack cocaine), strategies for giving brief HIV education to patients, and specific techniques for talking about sex with patients. Providers also wanted ongoing feedback about the Positive Steps program to substantiate their ongoing support and investment in it. As a result of provider requests during the formative interviews, the Positive Steps project staff met with clinic staff on a semiannual basis to provide updates and obtain feedback from the staff.

Of the 20 patients interviewed, 80% were open to the idea of receiving safer-sex counseling as a part of their routine clinic care and only one was already speaking to a doctor or counselor about safer sex. One patient said,

It's important to talk to me about (safer sex) to keep me in check.” Another patient put it this way: “I think it (talking about safer sex) is very important. It's getting easier. I think they just need to seriously talk about it. About 10 years ago people really didn't talk about it as much as they do now … it's getting much better.

Most patients preferred to be counseled by their medical provider, but felt that a prevention counselor would be acceptable if they were able to build a trusting relationship with that person.20 Patients provided a range of topics that they would like to see included in the safer-sex program including: risks associated with different sexual activities; proper use of condoms; sex with other HIV-positive partners and re-infection; the use of female condoms; HIV transmission; sexually transmitted infections (STIs); disclosure of HIV status to partners; and disclosure of HIV status to family and friends.18 Instead of using medical terminology, patients desired the use of common language to talk about prevention issues (“getting,” “giving,” “spreading,” etc. instead of “transmitting,” “protecting oneself or others,” “playing safe/r,” “being “careful” instead of “safer sex”). In response to these findings, we incorporated supplemental training topics including language common to patients, risk-reduction topics requested by patients and providers, and a review of the HIV epidemic and transmission in North Carolina.

In the formative interviews, both providers and patients expressed concern that having an HIV prevention program in the clinic could lead to breaches in patients' confidentiality. Providers indicated a strong commitment to maintaining patient trust and confidentiality.7 Providers requested a standard of care to address the opposing interests of current state laws (e.g., the law requiring patients exposing partners to risk to be reported) and patients' trust in their providers. For the purpose and duration of the Positive Steps program, a care plan and reporting recommendations resulted from discussions to specifically address the need for counseling and education of patients, who reported that they engaged in high-risk behaviors. The care plan, developed jointly by the clinic and the Public Health Department leadership, emphasized that counseling and education would be delivered to patients by trained clinic staff at the ID clinic first and would be reported to the public health department for partner tracing and notification if the clinic staff felt the health department's involvement was necessary because transmission risk was continuing.

Question 2: How often were HIV transmission risk screening and provider counseling delivered to patients during routine HIV care?

Chart review

Risk screeners were administered to patients by a nurse. Audits of risk screeners filed in patients' medical records showed that over 80% of scheduled patients were screened for HIV transmission risk behaviors during the first month that the Positive Steps program was initiated (Fig. 1A). Although screening rates fell subsequently, approximately 2 of 3 patients (mean of all remaining time points: 68%) were screened. Averaged across all six audit time points, 69% were screened (Fig. 1A). Very few patients refused to be screened (averaging only 1 patient per week).

FIG. 1.

A: Percent (n/N) of scheduled patients attending clinic who were screened for HIV transmission risks (data from chart review), Positive Steps intervention, North Carolina, 2004–2006. B: Percent (n/N) of patients screened, that received prevention counseling from a primary care provider (data from chart review), Positive Steps intervention, North Carolina, 2004–2006.

On the bottom of the screening form, primary care providers could indicate whether they delivered prevention counseling to patients. Based on information from the screeners, 90% of patients screened during the first two months of the Positive Steps implementation received counseling during that period and, on average, 72% of patients screened during the remaining periods were counseled (Fig. 1B). Averaged across all six audit time points, of those screened, 77% were counseled about HIV prevention. Among patients who received prevention counseling, the median time spent per patient was 7 minutes (range, 1–12 minutes) at 4 months, and 9 minutes (range, 1–38 minutes) approximately 9 months after Positive Steps implementation. Prevention specialist counseling services were implemented through the Positive Steps program. Referrals to those specialists averaged four patients each month (1% of the approximately 360 patient visits per month). Referrals to the state health department for partner tracing were few and averaged one each month; half of these referrals were initiated after the diagnosis of an STI.

Patient visit exit surveys

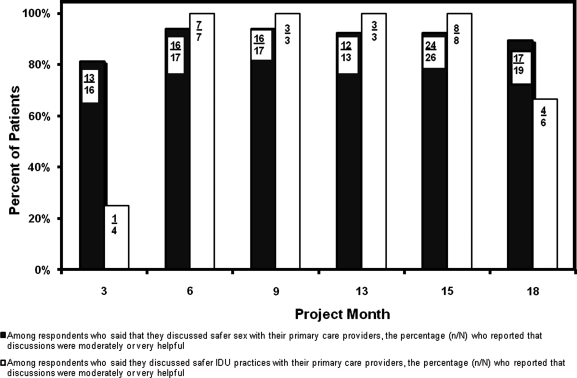

Self-administered visit exit surveys were collected at six time periods during the course of the Positive Steps implementation. Across all six survey periods, 65% of respondents were male, 35% were female, most self-identified as African American (62%), 29% self-identified as white, and the mean age was 41 years. Overall, 73% (155/213) of respondents reported being asked about safer sex by their primary care provider or someone else (nurse or social worker), and there was only small variation across survey periods (Fig. 2A). Overall, 51% (108/213) of respondents said they had safer-sex discussions with their primary care provider, and the percentage ranged from 40% to 60% across periods (Fig. 2A). Of respondents who had those discussions, 91% (98/108) reported that the discussions were very or moderately helpful (Fig. 3). Overall, 33% (70/213) of respondents reported being asked by their primary care provider about injection drug use practices and 15% (31/213) of respondents reported discussions with their primary care provider about safer injection practices (Fig. 2B). Relatively few patients reported discussions of injection practices presumably because only 11% of the clinic patient population had injection drug use as a mode of exposure to HIV. Of respondents who had discussions, 84% (26/31) reported that the discussions were very or moderately helpful (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

A: Percent (n/N) of patients who reported on the visit exit surveys that their providers asked about or discussed safer sex, Positive Steps Intervention, North Carolina, 2004–2006. B: Percent (n/N) of patients who reported on the visit exit surveys that their primary care providers asked about or discussed injection drug use (IDU) practices, Positive Steps Intervention, North Carolina, 2004–2006.

FIG. 3.

Among respondents who reported on their exit survey that their primary care provider discussed safer sex or safer injection drug use (IDU) practices with them, the percentage (n/N) who reported that the discussions were helpful, Positive Steps Intervention, North Carolina, 2004–2006.

Question 3: How did providers respond to integrating prevention interventions into the medical care of people living with HIV?

Post-implementation interviews of providers

A majority of providers completing the follow-up interviews (7/11) reported they were more aware of prevention issues than they had been prior to the implementation of the Positive Steps program in 2004. While the medical providers had previously been concerned with prevention issues, they reported that the initial training, as well as their continued experiences discussing HIV transmission risk behaviors with patients, had brought prevention to the “forefront” of their minds. One provider reflected on his experience with the Positive Steps program and his awareness of risk behaviors:

The preparation for the program as well as the program itself has led to us being more aware of the risks our patients are taking. So, I think our perceptions of risk, my perception of risk has increased because we are confronting it more and uncovering it more with the screener.

However, an equal number of providers, (7/11), mentioned time as a barrier to prevention counseling, noting that competing medical issues such as high viral loads, HIV medications, and other health issues took precedence over HIV prevention, which was often left to the end of a visit, if discussed at all. One provider explained his feelings about managing prevention counseling in light of a packed clinic schedule as follows:

One thing I do not do is schedule patients around my talking with patients about prevention. So, it is always shoe-horned in as an add-on to every visit. And so when other things take too long or other patients appear, prevention always gets bumped to deal with that need. So, I'll end with saying something like, “Stay safe out there.”

However, providers also expressed the idea that having prevention counselors available to provide patients with in-depth counseling sessions helped with time-consuming tasks such as contacting public health officers, and alleviated the time constraints they felt during clinic visits. One provider stated that,

Having these folks (prevention counselors) available has been a big bonus because (prevention) is an important issue, but when you have two patients sitting in there, just waiting to see you and you get someone who says they don't use condoms, so how many times can you handle that? It is just like having an extra set of hands to help you deal with it.

Most of the providers (9/11) reported that the risk screener prompted them to assess their patients' risk behaviors and counsel them accordingly. One provider said that the screener opened the door for discussion:

I think the written screen is helpful because it is something that we have to talk about. [Patients ask] “Why did you make me do this?” So it becomes a way to talk about it.

The screener was especially useful for task-oriented providers, who could document and “check off” their prevention counseling session on a single piece of paper. One provider put it this way:

Mostly I think (the risk screener is) a reminder that if I have the time I need to address (prevention counseling), or if I see something on there that raises a red flag that I need to address it.

Most providers (7/11) also felt the risk screeners were administered too frequently, placing undue emphasis on transmission risk to the detriment of other issues, such as the patients' medical issues or adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). This was felt to be especially true for the majority of patients who were seen as engaging in “low-risk” behaviors. Although, the risk screener was completed before the clinical encounter to reduce provider burden, one provider recommended streamlining the risk screener and having the provider administer the screener (instead of the nurse) to increase both patient and provider involvement in the risk screening process.

Post-implementation discussions about the risk-screening tool

In response to provider and patient feedback about the risk screener's rather solitary emphasis on HIV prevention, we revised the screener to include additional items assessing ART adherence, alcohol use, and patients' primary health concerns. We incorporated these changes once the Positive Steps evaluation was completed in October 2006. By screening for a range of issues, use of the screener was expected to interfere less with providers' ability to address other medical needs. Since the risk reduction checklist and questions about casual versus main partners were reported to be less helpful by both patients and providers, they were removed from the screening tool. Questions about sexual activity (yes or no) and the number and gender of partners were kept and patients continued to complete the risk screener at all routine visits. In addition, provider documentation of counseling was simplified for sustainability purposes by requiring only electronic medical record entry, with counseling monitoring activities now incorporated into the clinic's other Ryan White continuous quality improvement activities.

Discussion

Lewin's model of organizational change provided a useful framework for guiding the implementation and integration of the Positive Steps HIV prevention program into an infectious diseases clinic, affiliated with a large university-based medical center. Thoughtful planning and careful application of organizational change principles facilitated the process. To smoothly integrate the new program, providers needed to examine existing barriers and challenges and modify clinic procedures to accommodate ongoing patient, staff, and provider needs. Consensus building, early buy-in from organizational leaders, and staff empowerment were strategies employed to assist with integration and implementation of the Positive Steps program.21 Clear objectives and ongoing collection of process measures provided program transparency and an opportunity for program participants to take part in a constructive dialogue, which ultimately enhanced patient and provider acceptability of the Positive Steps program.

Lessons learned

Providers delivered counseling frequently to patients who completed the risk screener, suggesting that the screening information served as a starting point and prompted a discussion. Delivering the risk screener at every “routine” clinic visit, rather than at a predetermined frequency (i.e., quarterly), was feasible, although most providers reported that routine counseling at every visit was too frequent. Competing provider and nursing priorities (such as limited time, clinic flow, and other barriers), especially for patients needing frequent medical care, may have influenced whether the risk screener was completed and placed in the chart. The presence or absence of the screener may also have influenced the reported occurrence of counseling, because the screener was used to prompt counseling and that counseling was supposed to be documented on the screener form.

Providers incorporated brief counseling into routine visits successfully, but not universally. The private nature of questions about sexual behavior and drug use posed a barrier only for a minority of patients who declined to complete the screener. During the year after implementation, 50% of screened patients received counseling, suggesting that competing medical priorities may have prevented universal counseling at every routine medical visit.

Data on prevention counseling delivery were dependent on patient and provider recall, and it is possible that the counseling was over or under-reported. Nevertheless, both providers and patients reported similar frequencies of counseling, suggesting that the data reflected actual behavior. However, some counseling may have occurred and not been documented, and, additionally, some patients who were not screened may have been counseled. Thus, the prevalence of counseling may be higher than what we observed.

Sustaining the Positive Steps program

Based on post-implementation interviews and meetings with providers and ongoing patient feedback, sustaining the Positive Steps program is important to the HIV-care providers at the infectious disease clinic. Using train-the-trainer materials provided by the Mountain Plains AETC, as well as site-specific materials, the Positive Steps program has continued annual local trainings with new clinic staff, faculty and counselors. For example, providers recently identified patient disclosure of his or her HIV status to others as a difficult counseling issue and an in-service training was subsequently organized.

Conclusion

Documenting the experience of integrating and implementing a standardized prevention program in an infectious disease clinic provides insight regarding barriers to prevention delivery and allows a critical assessment of the feasibility and sustainability of a provider-delivered prevention program for people living with HIV/AIDS. We hope that this report allows other sites to replicate some of the activities we undertook, and profit from the lessons we learned in evaluating those activities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a contract from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with additional support from Health Resources and Services Administration's (HRSA's) Special Projects of National Significance program HA01289-02, and the UNC Centers for AIDS Research (P30-AI50410). The authors express appreciation for the contributions of the CDC Informatics and Statistical support team: Sanjyot Shinde, Sivakumar Rangarajan, and Vasu Panguluru. The authors would also like to acknowledge the providers and patients for their invaluable contribution to this paper.

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Hall HI. Song R. Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HIV/STD Prevention and Care Branch of the North Carolina. North Carolina HIV/STD Surveillance Reports, 2002–2005. www.epi.state.nc.us/epi/hiv. [Dec 15;2007 ]. www.epi.state.nc.us/epi/hiv

- 3.Institute of Medicine. No Time to Loose: The AIDS Crisis is not Over: Getting more from HIV prevention. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabral HJ. Tobias C. Rajabiun S, et al. Outreach program contacts: Do they increase the likelihood of engagement and retention in HIV primary care for hard-to-reach patients? AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobias C. Cunningham WE. Cunningham CO, et al. Making the connection: The importance of engagement and retention in HIV medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grodensky CA. Golin CE. Boland MS, et al. Translating concern into action: HIV care providers' views on counseling patients about HIV prevention in the clinical setting. AIDS Behav. 2007;12:404–411. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers JJ. Dawson-Rose C. Shade S, et al. Sex, risk and responsibility: Provider attitudes and beliefs predict HIV transmission risk prevention counseling in clinical care settings. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:30–38. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koester KA. Maiorana A. Vernon K, et al. Implementation of HIV prevention interventions with people living with HIV/AIDS in clinical settings: Challenges and lessons learned. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:17–29. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grol RP. Bosch MC. Hulscher ME, et al. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85:93–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimshaw JM. Thomas RE. MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii–iv. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glanz K. Rimer BK. Lewis FM. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Franscico, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies E. Van der Molen B. Cranston A. Using clinical audit, qualitative data from patients and feedback from general practitioners to decrease delay in the referral of suspected colorectal cancer. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:310–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustafson DH. Sainfort F. Eichler M, et al. Developing and testing a model to predict outcomes of organizational change. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:751–776. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewin K. Field Theory in Social Science. New York: Harper Collins; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner LI. Marks G. O'Daniels CM, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a clinic-based behavioral intervention: Positive Steps for HIV patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:627–635. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Napravnik S. Eron JJ. McKaig RG, et al. Factors associated with fewer visits for HIV primary care at a tertiary care center in the Southeastern U.S. AIDS Care. 2006;18:45–50. doi: 10.1080/09540120600838928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Napravnik S. Mikeal O. McKaig RG, et al. High risk for transmission of drug-resistant HIV variants among HIV-infected patients in routine clinical care. The 3rd IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment [poster}; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pence BW. Gaynes BN. Whetten K, et al. Validation of a brief screening instrument for substance abuse and mental illness in HIV-positive patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:434–444. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000177512.30576.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golin CE. Patel S. Tiller K, et al. Start talking about risks: Development of a Motivational Interviewing-based safer sex program for people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:S72–83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bowe CM. Lahey L. Armstrong E, et al. Questioning the “big assumptions.” Part I: Addressing personal contradictions that impede professional development. Med Educ. 2003;37:715–722. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]