Abstract

We used placental tissue to compare the imprinted gene expression of IGF2, H19, KCNQ1OT1, and CDKN1C of singletons conceived via assisted reproduction technology (ART) with that of spontaneously conceived (SC) singletons. Of 989 singletons examined (ART n = 65; SC n = 924), neonatal weight was significantly lower (P < .001) in the ART group than in the SC group, but placental weight showed no significant difference. Gene expression analyzed by real-time PCR was similar for both groups with appropriate-for-date (AFD) birth weight. H19 expression was suppressed in fetal growth retardation (FGR) cases in the ART and SC groups compared with AFD cases (P < .02 and P < .05, resp.). In contrast, CDKN1C expression was suppressed in FGR cases in the ART group (P < .01), while KCNQ1OT1 expression was hyperexpressed in FGR cases in the SC group (P < .05). As imprinted gene expression patterns differed between the ART and SC groups, we speculate that ART modifies epigenetic status even though the possibilities always exist.

1. Introduction

Assisted reproduction technology (ART) is associated with epigenetic alterations [1–3] that can affect fetal growth in animals and humans and usually results from imprinting. Followup studies of ART-conceived children have shown that ART does not increase the incidence of congenital abnormalities [4–10]; however, it increases the incidence of epigenetic disorder diseases, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS), Angelman Syndrome (AS), and Russell-Silver Syndrome (RSS) [11–17].

In BWS [MIM 130650] and RSS [MIM 180860], abnormal fetal growth is a major phenomenon, and abnormal prenatal development has been associated with the epigenetics of some imprinted genes. Reduced birth weight, which is occasionally observed in infants conceived by ART, is an important consideration as it is associated with adult diseases such as insulin insensitivity, polycystic ovary syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases [18–20]. Therefore, normal prenatal development may be very important not only for childhood health but also for long-term health. Here, we used human placental tissue to compare the imprinted gene expression of IGF2, H19, KCNQ1OT1, and CDKN1C genes known to be associated with fetal growth, in ART-conceived singletons with that in spontaneously conceived (SC) singletons.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 1302 singletons delivered at our center from June 2005 to March 2007 were enrolled in this study. Of these 1302 potential subjects, 313 were excluded due to complications. A total of 860 infants had appropriate-for-date (AFD) birth weight (2500 g ≤ AFD birth weight < 3500 g), 64 cases exhibiting fetal growth retardation (FGR) had a birth weight of <2500 g, and 65 cases had a birth weight of ≥3500 g. Thus, 989 subjects (ART n = 65; SC n = 924) were assessed with 3 idiopathic FGR cases in the ART group and 61 in the SC group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| ART (n) | SC (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFD (2500 g ≤, <3500 g) | 62 | 798 | 860 |

| FGR (≤ 2500 g) | 3 | 61 | 64 |

| OG (≥3500 g) | — | 65 | 65 |

| Total | 65 | 924 | 989 |

n: number of cases, AFD: appropriate-for-date, FGR: fetal growth retardation, OG: over growth, ART: assisted reproductive technology, and SC: spontaneous conception.

For the gene expression study, placental tissue was collected from 297 cases after receiving informed consent under the IRB protocol of our center for genetic analysis (Table 2). Total RNA was extracted from the fetal placenta, and reverse transcription was performed. Gene expressions of IGF2, H19, KCNQ1OT1, and CDKN1C were analyzed by real-time PCR with GAPDH serving as the endogenous control.

Table 2.

Imprinted gene expression analysis in placental tissue samples.

| ART (n) | SC (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFD (≥2500 g, <3500 g) | 45 | 173 | 218 |

| FGR (≤2500 g) | 3 | 51 | 54 |

| OG (≥3500 g) | — | 25 | 25 |

| Total | 48 | 249 | 297 |

n: number of cases, AFD: appropriate-for-date, FGR: fetal growth retardation, OG: over growth, ART: assisted reproductive technology, and SC: spontaneous conception.

3. Results and Discussion

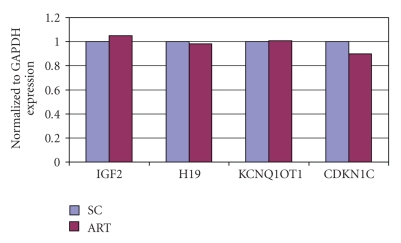

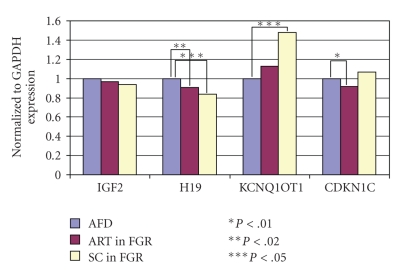

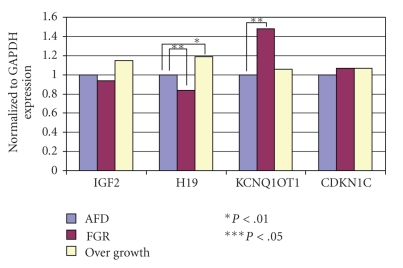

The mean birth weight was significantly lower (P < .001) in the ART group (2905.1 ± 459.0 g) than in the SC group (3607.9 ± 589.9 g). The mean placental weight, however, showed no significant difference (ART = 689.3 ± 152.6 g; SC = 613.0 ± 142.5 g) (Table 3). Gene expression patterns in the AFD birth weight cases were similar in both the ART and SC groups (Figure 1). H19 expression was reduced in FGR cases both in the ART and SC groups compared with the AFD cases (P < .02 and P < .05, resp.) (Figure 2). Conversely, H19 expression was significantly enhanced in SC cases with a birth weight of ≥3500 g (P < .01) (Figure 3). On the other hand, CDKN1C expression was reduced in ART cases with FGR (P < .01), and KCNQ1OT1 appeared to be hyperexpressed in SC cases with FGR (P < .05) (Figure 2). The expression of other genes examined showed no difference from the control.

Table 3.

Birth weight and placenta weight.

| Weight (g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Neonate | Placenta | |

| ART | 65 | 2905.1 ± 459.0* | 589.3 ± 152.6 |

| SC | 924 | 3607.9 ± 589.9* | 613.0 ± 142.5 |

*P < .001. n: number of cases, ART: assisted reproductive technology, and SC: spontaneous conception.

Figure 1.

Gene expression of placental tissue. ART versus SC in AFD birth weight cases. ART: assisted reproductive technology. SC: spontaneous conception. AFD: appropriate-for-date. Results of gene expression analysis compared with the endogenous control GAPDH. In AFD birth weight cases, gene expression patterns were similar in both the ART and SC groups.

Figure 2.

Gene expression of placental tissue. ART versus SC in FGR cases. There were no differences in the gene expression of IGF2; however, H19 expression was significantly reduced in FGR cases both in the ART and SC groups compared with the AFD birth weight cases (P < .02 and P < .05, resp.). Conversely, KCNQ1OT1 was hyperexpressed in FGR cases in the SC group (P < .05), while CDKN1C expression was reduced in FGR cases in the ART group (P < .01).

Figure 3.

Gene expression in placental tissue. FGR and birth weight ≥3500 g cases in the SC group. H19 expression was significantly reduced in FGR cases, but significantly enhanced in cases with a birth weight of ≥3500 g (P < .01).

The results demonstrated that birth weight was significantly lower in the ART group than in the SC group, which is in agreement with the results of other studies [21–23]. Some followup studies of ART-conceived children suggest that low birth weight is due to multiple pregnancies. However, even in singleton cases, low birth weight has been observed in infants conceived by ART. For cases conceived using fresh embryo replacement, birth weight was comparably lower than that for cases conceived using cryopreserved embryos [24, 25]. Although we did not separate cases conceived with fresh embryos and cryopreserved embryos, many cases in this study were conceived by fresh embryo replacement. On the other hand, placental weight showed no significant difference between the ART and SC groups. In other studies, however, placental thickness was significantly larger in ART cases than in SC cases, but there were no differences in morphological or histopathological features of the placenta between both groups [26]. There were no differences in the gene expression patterns in the AFD cases between the ART and SC groups. However, the expression of H19, a paternally methylated imprinted gene, was reduced in FGR cases in both the ART and SC groups. As maternally expressed genes such as H19 enhance fetal development, the hypoexpression of H19 affects fetal development. Here, we established the relationship between the hypoexpression of H19 and reduced fetal weight. Additionally, CDKN1C, another maternally expressed gene, exhibited reduced expression in FGR cases conceived by ART. In contrast, the expression of KCNQ1OT1, a paternally expressed gene with a complementary relationship to CDKN1C, was enhanced in FGR cases conceived by natural conception. In this study, we confirmed differences in the expression of imprinted genes in the placental tissue of infants conceived by ART. However, even in the SC cases, epigenetic alteration has been observed. The loss of imprinting on genes located on chromosome 11 is identified as a cause of poor fetal growth in humans [27], which is also reflected in our study. We postulate that ART could affect the epigenetic characteristics of male and female gametes or it can have an impact on early embryogenesis. Additionally, ART could be associated with an increased risk of genomic imprinting abnormalities as epigenetic reprogramming occurs during gametogenesis or immediately following fertilization [28–32].

4. Conclusions

Imprinted gene expression patterns of placental tissue in FGR cases were altered compared with cases of normal fetal growth. However, imprinted gene expression patterns of placental tissue in ART cases were different from those of SC cases. In cases with a birth weight of ≥3500 g, gene expression differed from cases with standard fetal growth. While we recognize the possibility of changes in epigenetic status in any pregnancy, we speculate that epigenetic status is altered by ART. Although ART has been widely accepted and safety performed, epigenetics should remain an important factor for evaluating the safe development of reproductive medicine, as well as for considering the health of the next generation.

References

- 1.Maher ER. Imprinting and assisted reproductive technology. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(1):R133–R138. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen C, Reardon W. Assisted reproduction technology and defects of genomic imprinting. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112(12):1589–1594. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Epigenetics and assisted reproductive technology: a call for investigation. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;74(4):599–609. doi: 10.1086/382897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonduelle M, Desmyttere S, Buysse A, et al. Prospective follow-up study of 55 children born after subzonal insemination and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Human Reproduction. 1994;9(9):1765–1769. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonduelle M, Legein J, Derde M-P, et al. Comparative follow-up study of 130 children born after intracytoplasmic sperm injection and 130 children born after in-vitro fertilization. Human Reproduction. 1995;10(12):3327–3331. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonduelle M, Legein J, Buysse A, et al. Prospective follow-up study of 423 children born after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Human Reproduction. 1996;11(7):1558–1564. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonduelle M, Wilikens A, Buysse A, et al. Prospective follow-up study of 877 children born after intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), with ejaculated epididymal and testicular spermatozoa and after replacement of cryopreserved embryos obtained after ICSI. Human Reproduction. 1996;11(supplement 4):131–155. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.suppl_4.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonduelle M, Devroey P, Liebaers IA, Van Steirteghem A, Rosenwaks Z. Commentary: major defects are overestimated. British Medical Journal Articles. 1997;7118:1265–1266. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palermo GD, Colombero LT, Schattman GL, Davis OK, Rosenwaks Z. Evolution of pregnancies and initial follow-up of newborns delivered after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(23):1893–1897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurinczuk JJ, Bower C. Birth defects in infants conceived by intracytoplasmic sperm injection: an alternative interpretation. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7118):1260–1266. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7118.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBaun MR, Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Association of in vitro fertilization with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and epigenetic alterations of LIT1 and H19 . The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72(1):156–160. doi: 10.1086/346031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher ER, Brueton LA, Bowdin SC, et al. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and assisted reproduction technology (ART) Journal of Medical Genetics. 2003;40(1):62–64. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gicquel C, Gaston V, Mandelbaum J, Siffroi J-P, Flahault A, Le Bouc Y. In vitro fertilization may increase the risk of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome related to the abnormal imprinting of the KCNQ1OT gene. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72(5):1338–1341. doi: 10.1086/374824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox GF, Bürger J, Lip V, et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection may increase, the risk of imprinting defects. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2002;71(1):162–164. doi: 10.1086/341096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ørstavik KH, Eiklid K, Van der Hagen CB, et al. Another case of imprinting defect in a girl with Angelman syndrome who was conceived by intracytoplasmic sperm injection. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;72(1):218–219. doi: 10.1086/346030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lidegaard Ø, Pinborg A, Andersen AN. Imprinting disorders after assisted reproductive technologies. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;18(3):293–296. doi: 10.1097/01.gco.0000193006.42910.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogata T, Kagami M. Assisted reproductive technology and imprinting failure. Journal of Mammalian Ova Research. 2006;23:158–162. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Junien C, Gallou-Kabani C, Vigé A, Gross M-S. Nutritional epigenomics of metabolic syndrome. Medecine/Sciences. 2005;21(4):396–404. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2005214396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eleftheriades M, Creatsas G, Nicolaides K. Fetal growth restriction and postnatal development. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1092:319–330. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin-Gronert MS, Ozanne SE. Experimental IUGR and later diabetes. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2007;261(5):437–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hourvitz A, Pri-Paz S, Dor J, Seidman DS. Neonatal and obstetric outcome of pregnancies conceived by ICSI or IVF. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2005;11(4):469–475. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen VM, Wilson RD, Cheung A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2006;28(3):220–250. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palermo GD, Neri QV, Takeuchi T, Squires J, Moy F, Rosenwaks Z. Genetic and epigenetic characteristics of ICSI children. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2008;17(6):820–833. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belva F, Henriet S, Van Den Abbeel E, et al. Neonatal outcome of 937 children born after transfer of cryopreserved embryos obtained by ICSI and IVF and comparison with outcome data of fresh ICSI and IVF cycles. Human Reproduction. 2008;23(10):2227–2238. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinborg A, Loft A, Aaris Henningsen AK, Rasmussen S, Rasmussen S, Nyboe Andersen A. Infant outcome of 957 singletons born after frozen embryo replacement: the Danish National Cohort Study 1995–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.091. Fertility and Sterility. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniel Y, Schreiber L, Geva E, et al. Do placentae of term singleton pregnancies obtained by assisted reproductive technologies differ from those of spontaneously conceived pregnancies? Human Reproduction. 1999;14(4):1107–1110. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.4.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo L, Choufani S, Ferreira J, et al. Altered gene expression and methylation of the human chromosome 11 imprinted region in small for gestational age (SGA) placentae. Developmental Biology. 2008;320(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann S, Bergmann M, Bohle RM, Weidner W, Steger K. Genetic imprinting during impaired spermatogenesis. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2006;12(6):407–411. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato A, Otsu E, Negishi H, Utsunomiya T, Arima T. Aberrant DNA methylation of imprinted loci in superovulated oocytes. Human Reproduction. 2007;22(1):26–35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reik W, Dean W, Walter J. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science. 2001;293(5532):1089–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1063443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan HD, Santos F, Green K, Dean W, Reik W. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammals. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(1):R47–R58. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Epigenetics and assisted reproductive technology: a call for investigation. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;74(4):599–609. doi: 10.1086/382897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]