SUMMARY

A method for simultaneously quantifying dopamine, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and four metabolically related compounds has been developed, permitting more efficient neurochemical examination of these often interrelated biogenic amine systems. The method uses high-performance liquid chromatographic separation of these compounds on a C18 reversed-phase column with a buffered mobile phase containing methanol as an organic modifier and heptanesulfonate as an ion-pair reagent. Using 5-hydroxy-N-methyltryptamine as an internal standard and electrochemical detection, chromatography time is less than 12 min. Sample preparation simply involves the addition of internal standard, homogenization in the mobile phase, centrifugation and injection of the supernatant into the chromatograph. The method is sensitive to a tissue content of these compounds of less than 1 ng. The utility of this method for neuropharmacological—neurochemical studies is illustrated with studies using inhibitors of monoamine oxidase (pargyline) and aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (RO 4-4602).

INTRODUCTION

The involvement of dopamine- and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)-containing neuronal systems in the function of the central nervous system (CNS) is well documented. Evidence obtained from diverse lines of investigation support the existence of functional interactions between neuronal elements containing these two putative neurotransmitters [1—3]. It is therefore of interest to be able to assess simultaneously changes in the functional state of both of these systems.

Biochemical determinations of the rate of neurotransmitter turnover have proven to be useful estimates of the activity of neuronal systems. For dopamine systems, the available nonradiometric techniques include: (1) measurement of the rate of accumulation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) following decarboxylase inhibition [4]; (2) the rate of decrease in dopamine concentration following synthesis inhibition with α-methyltyrosine [5]; and (3) the concentration of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) or 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (HVA) at a steady state [6,7] or following inhibition of their formation or transport [8,9]. Similarly, the biochemical estimation of changes in 5-HT turnover have been employed as an index of changes in the functional state of 5-HT neurons in the CNS. These techniques include: (1) measurement of the rate of accumulation of 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) following decarboxylase inhibition [4,10]; (2) the rate of accumulation of 5-HT following inhibition of its metabolism [11,12]; and (3) the concentration of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) at a steady state [13] or following inhibition of its formation [11] or transport [14].

The heterogeneous distribution, function, and regulation of dopamine and 5-HT systems in the CNS necessitates the use of analytical techniques with sensitivity requisite for determinations in small brain regions. A variety of separation and detection methods have been used to quantify the precursors and metabolites of dopamine and 5-HT. Of these techniques, the greatest degrees of flexibility, sensitivity and specificity have been obtained using either gas chromatography with electron-capture or mass fragmentographic detection [15—21], or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using fluorometric or electrochemical detection [22—37]. However, each of these techniques has potential shortcomings in at least one of the following criteria: speed; sensitivity; specificity; flexibility; sample purification and/or concentration; use of internal standards to monitor recovery during sample preparation; or complexity of instrumentation.

The present study reports a method for the simultaneous determination of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT and 5-HIAA in samples from small brain regions by means of ion-pair, reversed-phase HPLC with electrochemical detection. N-Methyl-5-hydroxytryptamine is used as an internal standard. This assay offers considerable advantages in terms of ease of sample preparation, internal standardization and versatility, and offers sufficient sensitivity to perform accurate determinations in tissue samples as small as 1 mg.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents and drugs

Chemicals were obtained from the following sources: dopamine hydrochloride, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid, 5-hydroxytryptamine creatinine sulfate and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.); 5-hydroxytryptophan from Calbiochem (Los Angeles, CA, U.S.A.); 5-hydroxy-N-methyltryptamine oxalate (N-methyl-5-HT) from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, U.S.A.); sodium 1-heptane-sulfonate from Eastman-Kodak (Rochester, NY, U.S.A.); pargyline hydrochloride from Abbott Laboratories (North Chicago, IL, U.S.A.); and RO 4-4602 [N-(DL-seryl-N)-(2,3,4-trihydroxybenzyl)hydrazine] from Hoffmann-LaRoche (Nutley, NJ, U.S.A.). Reagent grade methanol (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, NJ, U.S.A.) was used as supplied.

Apparatus

A Laboratory Data Control (Riviera Beach, FL, U.S.A.) ConstaMetric IIG solvent delivery pump was used in conjunction with a TL-5 glassy carbon electrode and an LC-4 controller, both from Bioanalytical Systems (West Lafayette, IN, U.S.A.). The detector potential was maintained at 0.75 V vs. a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. A six port rotary valve (Model 7125, Rheodyne, Berkeley, CA, U.S.A.) with a 500-μ1 sample loop was used for sample injection. Chromatographic separations were performed using a 25 cm × 4.6 mm I.D. stainless-steel column packed with octadecylsilane (C18) on microparticulate (5 μm) silica gel (Spherisorb ODS, Applied Science Labs., State College, PA, U.S.A.). A precolumn filter with a 2-μm frit (Rheodyne) effectively minimized the accumulation of particulate matter on the analytical column.

Chromatography

The mobile phase was a mixture of 0.1 M citrate, 0.075 M Na2HPO4, 0.75 mM sodium heptanesulfonate and 14% methanol (v/v). After adjusting to pH* 3.9, the mobile phase was filtered through a 0.45-μm filter (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.) and degassed under vacuum with ultrasonic agitation. All separations were performed isocratically at a flow-rate of 1.5 ml/min.

Standards

Stock solutions of the reference and internal standards were prepared in the mobile phase at a concentration of 1 μg/μl (calculated as the free compound) and stored at 4°C. Working solutions (1 ng/μl) were prepared at weekly intervals by a 1:1000 dilution of the stock solutions using the mobile phase as the diluent.

Calculations

Standard curves were prepared by analyzing a series of standard solutions containing a fixed amount (10 or 25 ng) of the internal standard and varying amounts of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT and 5-HIAA. These standards, in 400-μl aliquots of the mobile phase, were subjected to the identical preparative procedures used for tissue samples. The ratio of the detector response for each compound versus that of the internal standard was determined for each sample and standard. The concentrations of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT and 5-HIAA in tissue samples were calculated from the ratio of their detector response relative to that of the internal standard using the slope and intercept of the standard curve.

Sample preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200—275 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wimington, MA, U.S.A.) were sacrificed by decapitation and the brain rapidly removed. The olfactory tubercles, nucleus accumbens and striata were dissected and placed in 500-μl nalgene tubes (No. 1801, Denville Scientific, Denville, NJ, U.S.A.) containing 400 μl of mobile phase and the internal standard (10 or 25 ng). Samples were homogenized with an ultrasonic cell disrupter (Model 185, Branson, Danbury, CT, U.S.A.) and centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C in a microcentrifuge (Model 5412, Brinkmann, Westbury, NY, U.S.A.). A 100—200-μl aliquot of either the standards or tissue sample supernatants was injected into the chromatograph. The homogenate pellet was assayed for protein content with the Folin reagent [38] using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effects of methanol, heptanesulfonate, and pH on compound retention

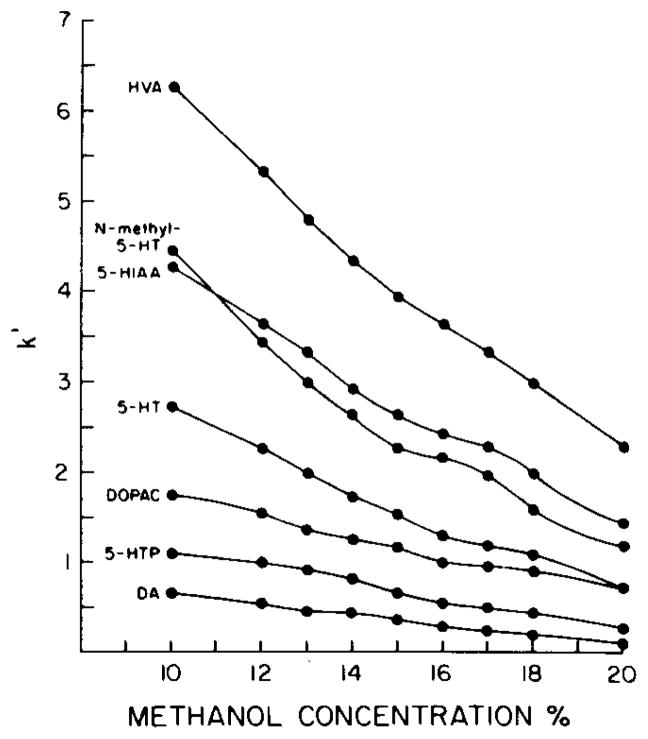

Functional group selectivity was optimized by alterations in the nature and relative concentrations of the mobile phase components. The relative retention (capacity factor, k′) of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT, 5-HTP and 5-HIAA was found to be a function of the methanol and heptanesulfonate concentrations, as well as of the pH of the mobile phase. Decreasing the aqueous characteristics of the mobile phase by increasing the methanol concentration produced a concentration-dependent decrease in k′ for all compounds (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of methanol concentration of the mobile phase on the retention of DA, 5-HTP, DOPAC, 5-HT, 5-HIAA, N-methyl-5-HT and HVA. Mobile phase: citrate—Na2HPO4, 0.75 mM heptanesulfonate, pH 3.9. The capacity factor, k′, was calculated by k′ = (tR − tvv) tvvwhere tR is the retention time of the compound of interest and tvv the retention time of an unretarded component (representing the time to displace one column void volume).

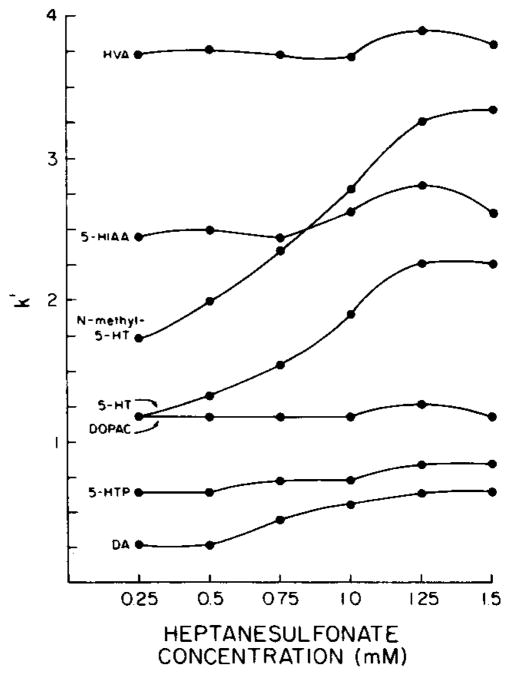

Ion-pair chromatography has been demonstrated to be effective in minimizing the peak tailing attributed to secondary interactions between polar ionogenic compounds and unreacted silanol groups on the silica surface and, more importantly, in controlling the relative retention of such compounds [39—42]. The addition of heptanesulfonate to the mobile phase produced a concentration-dependent increase in the retention of the protonated amines, i.e. dopamine, 5-HT and N-methyl-5-HT (Fig. 2). Pentanesulfonate, a less hydrophobic ion-pair reagent, did not facilitate the chromatographic separation of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT and 5-HIAA as completely as was possible using heptanesulfonate.

Fig. 2.

Effect of heptanesulfonate concentration of the mobile phase on the retention of DA, 5-HTP, DOPAC, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT, 5-HIAA and HVA. Mobile phase: citrate— Na2HPO4, 14% methanol, pH 3.9. See legend to Fig. 1 for derivation of k′.

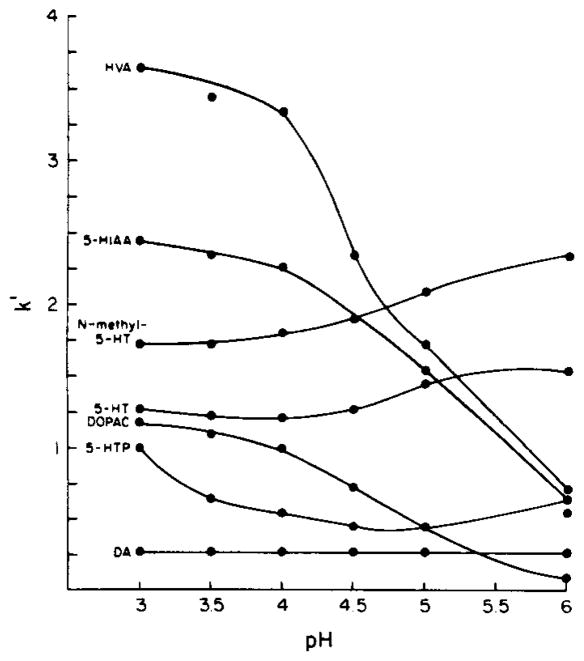

The observed influence of mobile phase pH on the relative retention of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT and 5-HIAA is in good agreement with predictions based on the degree of ionization at a given pH (Fig. 3). As the mobile phase pH increases relative to the pKa values of DOPAC, HVA and 5-HIAA, they are deprotonated to a greater extent, resulting in a decrease in their capacity factors (Fig. 3). Conversely, the calculated capacity factors for the amines (dopamine, 5-HT and N-methyl-5-HT) are relatively unaffected by the pH range (3—6) examined in the present study since their pKa values exceed the highest mobile phase pH tested. The capacity factors for the amino acid 5-HTP exhibit a concave downward relationship with increasing mobile phase pH. This is probably due to initial deprotonation of the carboxyl group to form the more polar zwitterion followed by deprotonation of the amino group to yield the amino carboxylate anion.

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH of the mobile phase on the retention of DA, 5-HTP, DOPAC, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT, 5-HIAA and HVA. Mobile phase: citrate—Na2HPO4, 0.75 mM heptanesulfonate, 14% methanol. Orthophosphoric acid (85%) or 1 N sodium hydroxide were used to titrate the mobile phase to the desired pH. See legend to Fig. 1 for derivation of k′.

Internal standardization

The use of internal standards in quantitative analytical procedures is generally considered to be superior to direct calibration. The addition of N-methyl-5-HT to standards and tissue samples effectively controlled for variable volumes injected and within-run variations in column or detector electrode performance. The ratio of the detector response to varied amounts (0.1—50 ng) of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT and 5-HIAA relative to a constant amount of N-methyl-5-HT (10 ng) was a linear function of concentration. Correlation coefficients for each compound were generally greater than 0.99. 5-Hydroxy-2-indolecarboxylic acid (Aldrich) elutes after HVA and can be used in place of, or in addition to, N-methyl-5-HT as an internal standard. Although this compound simplifies establishing optimal mobile phase parameters for a given column, it increases the total chromatography time, thereby decreasing sample throughput.

Tissue protein precipitation

The relative effectiveness of the mobile phase in precipitating proteins from tissue homogenates was also determined. The whole brain from a rat was minced and duplicate groups of 10, 50 or 100 mg samples were collected. One group was homogenized in 400 μl of the mobile phase and the other homogenized in 400 μl of 0.1 M perchloric acid. Following centrifugation and removal of the supernatants, the protein content of the pellet was determined (Table I). It is apparent from these data that the mobile phase is at least as effective as 0.1 M perchloric acid in precipitating tissue protein.

TABLE I.

PROTEIN CONTENT (mg) OF BRAIN MINCES HOMOGENIZED IN MOBILE PHASE* OR 0.1 M PERCHLORIC ACID

| Approximate tissue weight (mg) | Solvent |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mobile phase | 0.1 M perchloric acid | |

| 10 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 1.05 ± 0.15 |

| 50 | 5.4± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| 100 | 11.5 ±0.6 | 9.8 ± 0.4 |

See text for mobile phase composition.

Values represent mean ± S.E.M. for 3 separate determinations.

Chromatographic interference

The utility of any analytical method is limited by the extent to which endogenous or exogenous substances interfere with the separation and detection of the compounds of interest. In this assay, interference will occur only when such substances coelute with one or more of the compounds of interest and are significantly oxidized at the detector electrode potential used. A series of catechol and indole derivatives were examined to determine if either or both of these criteria were applicable. Epinephrine (EPI), norepinephrine (NE) and DOPA had significant electrochemical activity within the range of detector potentials examined (0.55—0.75 V). However, these polar compounds elute in the solvent front and thus would not interfere. Conversely, tyramine and tryptophan coelute with 5-HTP and N-methyl-5-HT, respectively, but produce little or no detector response at detector potentials less than 0.9 V (tryptophan) or 0.8 V (tyramine). The 3-O-methylated metabolites of NE and EPI, normetanephrine and metanephrine, respectively, eluted immediately prior to and following dopamine and were electrochemically inactive at detector potentials less than 0.6 V. The deaminated metabolites of NE, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxymandelic acid (VMA) and 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG), elute in the solvent front and prior to 5-HTP, respectively. The 3-O-methylated metabolite of dopamine, 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT), eluted between and was incompletely resolved from DOPAC and 5-HT. In agreement with Shoup and Kissinger [43] no detector response was obtained for 3-MT at detector potentials less than 0.6 V.

Of these potentially interfering compounds, only 3-MT is a particular source of concern when assaying dopaminergic systems. Although it interfered slightly with the quantification of DOPAC and 5-HT, the 3-MT content of the rat brain is relatively small, and does not compromise the overall accuracy of the assay. Moreover, interference attributed to 3-MT may be eliminated by sacrificing the rats by head focused microwave irradiation, or by decreasing the detector electrode potential to 0.6 V. Either course effectively eliminates this problem, although the latter method results in a concomitant decrease in the electrochemical activity of HVA.

Sensitivity and within-run reproducibility

Detection limits (in terms of compound injected from an aqueous solution) ranged from 20—60 pg for dopamine, DOPAC, 5-HTP, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT and 5-HIAA and 50—150 pg for HVA, depending on column condition. The within-run precision of the assay was determined by processing and assaying ten 50-μl aliquots of a sample obtained by homogenizing a single rat striatum in 500μl of mobile phase containing 250 ng of N-methyl-5-HT. The estimated coefficients of variation ranged from 6.3% (5-HIAA) to 3.1% (dopamine).

Effects of volume of sample injected

It is generally accepted that as the volume injected into the HPLC system increases, peak broadening may occur, resulting in a deterioration of the separation of adjacent chromatographic peaks. This assumption has limited the number of liquid—liquid or liquid—solid sample purification techniques which can be used in conjunction with HPLC, as their use compromises the overall sensitivity by generating dilute solutions from which a finite volume can be injected. The effect of injection volume on peak symmetry and resolution was examined by injecting solutions containing 50 ng of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT, N-methyl-5-HT and 5-HIAA in varying volumes (20—200 μl). The peak to peak resolution (Rs) was calculated according to Brown and Krstulovic [44]:

where V and W are the retention volume and base peak width, respectively, for compounds 1 and 2. No significant differences in the resolution of adjacent peaks (Rs ≥ 1.35 in all cases) were noted with increasing injection volume.

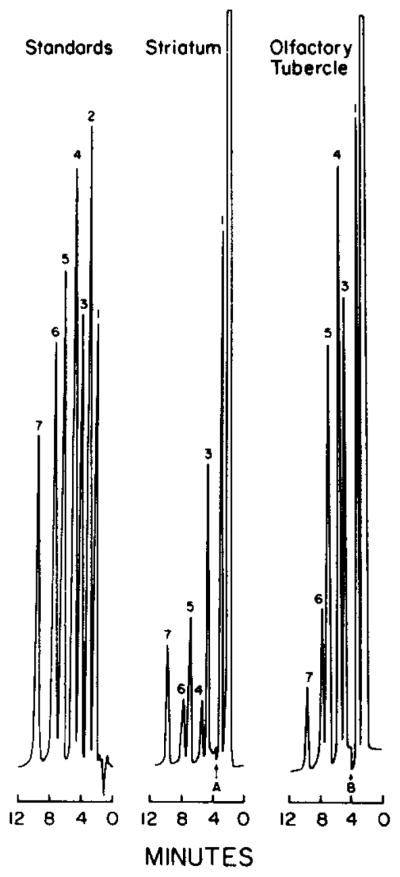

Quantitative determinations

The present method permits the simultaneous determinatin of dopamine, 5-HT, their deaminated metabolites, as well as 5-HTP (the immediate precursor of 5-HT), from samples of small brain regions. Representative chromatograms of standards and of samples of rat striatum or olfactory tubercle are shown in Fig. 4. The effects of pargyline and RO 4-4602 on the concentrations of these compounds in the striatum, olfactory tubercle and nucleus accumbens were determined to demonstrate the utility of the present method (Table II). The tissue concentrations of dopamine, 5-HT and DOPAC are in agreement with those previously reported [45—47]. The inhibition of monoamine oxidase activity by pargyline increased the concentrations of dopamine and 5-HT, and decreased the concentrations of DOPAC, HVA and 5-HIAA, in all brain regions examined. The inhibition of aromatic amino acid decarboxylase activity by RO 4-4602 increased the 5-HTP concentrations in all three brain regions to detectable concentrations. The concentrations of dopamine and 5-HT in the striatum and olfactory tubercle, but not the nucleus accumbens, were significantly decreased following RO 4-4602 treatment.

Fig. 4.

Chromatograms of 50 μl of a mixture containing 1 ng/μl of the reference and internal standards and of supernatants from rat striatum or olfactory tubercles. Peaks: 1 = DA; 2 = 5-HTP; 3 = DOPAC; 4 = 5-HT; 5 = N-methyl-5-HT; 6 = 5-HIAA; 7 = HVA. Detector sensitivities (using a 1-V recorder) were: 50 nA/V for standards; A = change of sensitivity from 200 to 50 nA/V; B = change of sensitivity from 50 to 20 nA/V. See text for chromatography conditions.

TABLE II.

EFFECTS OF PARGYLINE OR RO 4-4602 ON THE CONCENTRATIONS OF DA, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT AND 5-HIAA IN THE STRIATUM, OLFACTORY TUBERCLE AND NUCLEUS ACCUMBENS

| Treatment | Protein (ng/mg) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA | DOPAC | HVA | 5-HTP | 5-HT | 5-HIAA | |

| Striatum | ||||||

| Saline | 90.3 ± 6.7 | 17.2 ±1.2 | 9.3 ±0.9 | – | 4.6 ±0.5 | 6.4 ± 0.6 |

| Pargyline | 112.0 ±6.5* | 0.58 ±0.12* | 1.4 ± 0.08* | – | 8.3 ± 0.8* | 4.1 ± 0.4* |

| RO 4-4602 | 57.4 ± 5.3* | 16.1 ± 4.9 | 8.2 ±0.4 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.4* | 6.3 ± 0.7 |

| Olfactory tubercle | ||||||

| Saline | 41.3 ±4.0 | 7.8 ±1.0 | 3.1 ±0.8 | – | 10.1 ± 1.1 | 5.3 ± 0.8 |

| Pargyline | 55.9 ± 6.8* | 0.39 ±0.01* | 0.26 ± 0.04* | – | 15.7 ± 0.5* | 1.4 ± 0.2* |

| RO 4-4602 | 29.5 ± 3.9* | 5.8 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ±0.1 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | 6.3 ± 0.9* | 4.2 ± 0.3 |

| Nucleus accumbens | ||||||

| Saline | 59.3 ± 5.0 | 15.4 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ±0.6 | – | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 0.6 |

| Pargyline | 96.4 ± 2.5* | 1.1 ± 0.2* | 1.5 ± 0.09* | – | 9.0 ± 0.9* | 2.4 ± 0.2* |

| RO 4-4602 | 64.6 ± 7.2 | 13.8 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ±0.8 | 10.0 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 1.2 |

Animals were sacrificed 45 min after saline (1 ml/kg), pargyline (75 mg/kg) or RO 4-4602 (750 mg/kg). Brain regions were dissected and the samples assayed as described in Methods. Values represent means ± S.E.M. for 3 or 4 determinations.

Indicates values different from saline-injected controls at p < 0.05.

Considerations during daily use

It should be noted that differences in the chromatographic performance of commercially available C18 reversed-phase columns supplied by different manufacturers, or changes in performance that occur with continuous use of a given column, necessitate the periodic reoptimization of mobile phase parameters (heptanesulfonate and methanol concentrations, and pH). However, due to the weak surface energies of the bonded hydrocarbonaceous phase, a rapid re-equilibration with the column packing is possible when altering mobile phases [48]. Therefore, optimization of column performance, using the data in Figs. 1—3, can generally be accomplished in a few hours. In our experience, for columns supplied by different manufacturers, the necessary mobile phase alterations usually represent a change of less than 10% in any given parameter compared to values established with prior columns.

In summary, there are several salient features of the present method. The absolute and relative recovery of the compounds of interest was essentially complete. Furthermore, the ease of sample preparation permits the assay of 35—40 tissue samples plus a standard curve in one working day. The versatility of this method is demonstrated by the simultaneous determination of dopamine, DOPAC, HVA, 5-HTP, 5-HT, 5-HIAA and N-methyl-5-HT in a single sample. Obviously, use of the assay in whole or part can be tailored to the analytical demands of a particular experimental design.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by PHS grants Nos. ES-01104, HD-10570, AA-02334 and center grants HD-03110 and MH-33127. C.D.K. holds a postdoctoral National Research Service award (MH-07926), and R.B.M. is an NIEHS Young Investigator Awardee (ES-02087). The authors thank Ken Ellington for valuable assistance with the chromatography and Faygele ben Miriam for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

All references indicate the measured pH (“apparent pH”) of the aqueous methanol mixture referred to an aqueous standard buffer solution.

References

- 1.Fibiger HC, Miller JJ. Neuroscience. 1977;2:975. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuczenski R. Brain Res. 1979;164:217. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breese GR, Cooper BR, Mueller RA. Brit J Pharmacol. 1974;52:307. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1974.tb09714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlsson A, Davis JN, Kehr W, Kindqvist M, Atack CV. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmakol Exp Pathol. 1972;275:153. doi: 10.1007/BF00508904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brodie BB, Costa E, Blabac A, Neff NH, Smookler HH. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966;154:493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth RH, Murrin LC, Walter JR. Eur J Pharmacol. 1976;36:163. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(76)90268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karoum F, Neff NH, Wyatt RJ. Eur J Pharmacol. 1977;44:311. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(77)90304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiesel FA, Fri CG, Sedvall G. Eur J Pharmacol. 1973;23:104. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(73)90250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilk S, Watson E, Travis B. Eur J Pharmacol. 1975;30:238. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(75)90105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meek JL, Lofstrandh S. Eur J Pharmacol. 1976;37:377. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(76)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tozer TN, Neff NH, Brodie BB. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1966;153:177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neckers LM, Meek JL. Life Sci. 1976;19:1579. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhard JF, Jr, Wurtman R. Life Sci. 1977;21:1741. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neff NH, Tozer TN, Brodie BB. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1967;158:214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiesel FA, Fri CG, Sedvall G. J Neural Transm. 1974;35:319. doi: 10.1007/BF02205228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson E, Travis B, Wilk S. Life Sci. 1974;15:2167. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(74)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelpi E, Peralta E, Segura J. J Chromatogr Sci. 1974;12:701. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/12.11.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cattabeni F, Koslow SH, Costa E. Science. 1972;178:166. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4057.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swahn CG, Sandgarde B, Wiesel FA, Sedvall G. Psychopharmacology. 1976;48:147. doi: 10.1007/BF00423253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck O, Wiesel FA, Sedvall G. J Chromatogr. 1977;134:407. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)88539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Artigas F, Gelpi E. Anal Biochem. 1979;92:233. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90651-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meek JL, Neckers LM. Brain Res. 1975;91:336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meek JL. Anal Chem. 1976;48:375. doi: 10.1021/ac60366a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck O, Palmskog G, Hultman E. Clin Chim Acta. 1977;79:149. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(77)90472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis TP, Gehrke CW, Gehrke CW, Jr, Cunningham TD, Kuo KC, Gerhardt KO, Johnson HD, Williams CH. Clin Chem. 1978;24:1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller R, Oke A, Mefford I, Adams RN. Life Sci. 1976;19:995. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scratchley GA, Masoud AN, Stohs SJ, Wingard DW. J Chromatogr. 1979;169:313. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(75)85055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hefti F. Life Sci. 1979;25:775. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90522-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wightman RM, Plotsky PM, Strope E, Delcore R, Jr, Adams RN. Brain Res. 1977;131:345. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felice LJ, Kissinger PT. Anal Chem. 1976;48:794. doi: 10.1021/ac60370a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felice LJ, Bruntlett CS, Kissinger PT. J Chromatogr. 1977;143:407. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)80987-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasa S, Blank CL. Anal Chem. 1977;49:354. doi: 10.1021/ac50011a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponzio F, Jonsson G. J Neurochem. 1979;32:129. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb04519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warsh JJ, Chiu A, Godse DD, Coscina DV. Brain Res Bull. 1979;4:567. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(79)90043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gamier JP, Bousquet B, Dreux C. J Liquid Chromatogr. 1979;2:539. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koch DD, Kissinger PT. J Chromatogr. 1979;164:441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mefford IN, Barchas JD. J Chromatogr. 1980;181:187. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowry DH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittmer DP, Nuessle NO, Haney WG. Anal Chem. 1975;47:1422. doi: 10.1021/ac60358a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knox JH, Jurand J. J Chromatogr. 1976;125:89. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)93813-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraak JC, Jonker KM, Huber JFK. J Chromatogr. 1977;142:671. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)92076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Venne JLM, Hendrikx JLHM, Deelder RS. J Chromatogr. 1978;167:1. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shoup RE, Kissinger PT. Clin Chem. 1977;23:1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown PR, Krstulovic AM. Anal Biochem. 1979;99:1. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brownstein M, Saavedra JM, Palkovits M. Brain Res. 1974;79:431. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saavedra JM. Fed Proc, Fed Amer Soc Exp Biol. 1977;36:2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fekete MIK, Herman JP, Kanyicska B, Palkovits M. J Neural Transm. 1979;45:207. doi: 10.1007/BF01244409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karger BL, Giese RW. Anal Chem. 1978;50:1048A. [Google Scholar]