Abstract

Studies in monkeys have shown substantial neuronal reorganization and behavioral recovery during the months following a cervical dorsal root lesion (DRL; Darian-Smith [2004] J. Comp. Neurol. 470:134–150; Darian-Smith and Ciferri [2005] J. Comp. Neurol. 491:27–45, [2006] J. Comp. Neurol. 498:552–565). The goal of the present study was to identify ultrastructural synaptic changes post-DRL within the dorsal horn (DH). Two monkeys received a unilateral DRL, as described previously (Darian-Smith and Brown [2000] Nat. Neurosci. 3:476–481), which removed cutaneous and proprioceptive input from the thumb, index finger, and middle finger. Six weeks before terminating the experiment at 4 post-DRL months, hand representation was mapped electrophysiologically within the somatosensory cortex, and anterograde tracers were injected into reactivated cortex to label corticospinal terminals. Sections were collected through the spinal lesion zone. Corticospinal terminals and inhibitory profiles were visualized by using preembedding immunohistochemistry and postembedding γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) immunostaining, respectively. Synaptic elements were systematically counted through the superficial DH and included synaptic profiles with round vesicles (R), pleomorphic flattened vesicles (F; presumed inhibitory synapses), similar synapses immunolabeled for GABA (F-GABA), primary afferent synapses (C-type), synapses with dense-cored vesicles (D, mostly primary afferents), and presynaptic dendrites of interneurons (PSD). Synapse types were compared bilaterally via ANOVAs. As expected, we found a significant drop in C-type profiles on the lesioned side (~16% of contralateral), and R profiles did not differ bilaterally. More surprising was a significant increase in the number of F profiles (~170% of contralateral) and F-GABA profiles (~315% of contralateral) on the side of the lesion. Our results demonstrate a striking increase in the inhibitory circuitry within the deafferented DH.

INDEXING TERMS: ultrastructure, spinal cord injury, macaque, synaptic plasticity, dorsal horn

Peripheral and/or central injuries to the sensorimotor pathways are known to cause synaptic changes in central neuronal circuitry, including in the spinal cord, over the postinjury weeks and months. However, the details of these changes are complex and are poorly understood even in the most commonly used rodent models.

The primary afferent neuron can be damaged by various injuries, including those to peripheral nerves, and proximal to the dorsal root entry zone within the CNS. Damage at each level produces a very different environment within the spinal cord and a different prognosis for recovery and neuronal reorganization. Peripheral nerves retain the capacity for regeneration throughout life, so, when a nerve regrows, changes within the spinal circuitry may be transient. Central primary afferent injuries do not result in the regeneration of cut axons, but there is frequently sparing of input from the affected periphery via alternate or distributed parallel pathways (e.g., dorsal column, spinothalamic, spinocervical, propriospinal).

A dorsal rhizotomy, which we examined in this study, is also different. Transected axons that once projected into the spinal cord do not regrow into the dorsal horn, and functional recovery is possible only if there is some sparing of primary afferents within intact dorsal rootlets adjacent to the rhizotomy that continue to innervate the periphery (Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005). With even a small amount of sparing, reorganization can occur within the spinal cord and at higher levels of the neuraxis (Darian-Smith, 2007), and a significant recovery of function can result (Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005). During the initial weeks, severed primary afferent axons undergo Wallerian degeneration, and the resulting debris is largely removed by the end of the first month in the monkey (Ralston and Ralston, 1979b). Compared with a central spinal injury (Yang et al., 2006), gliosis and inflammation are minimal within the spinal dorsal horn (Vessal et al., 2007), and reorganization of the remaining circuitry can occur under more favorable circumstances.

Deafferentation at any level of the primary afferent will alter the normal balance of excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms within the dorsal horn, which are critical to the normal functioning of the spinal circuitry. However, the disruption will differ depending on the location of the injury. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the most ubiquitous of the inhibitory neurotransmitters in the superficial spinal cord, and rat studies have shown that GABA-immunoreactive (GABA-ir) neurons are evenly distributed in these laminae and make up ~33% of the overall neuron population (Todd and Sullivan, 1990; Castro-Lopez et al., 1993). The main actions of GABAergic neurons in the spinal cord are the presynaptic inhibition of primary afferent terminals and the postsynaptic inhibition of dorsal horn neurons (including interneurons, sensory projection neurons, and motor neurons in the ventral horn).

Studies that have examined GABAergic circuitry following peripheral injury typically report a reduction of inhibitory mechanisms (Castro-Lopes et al., 1993; Ibuki et al., 1997; Ralston et al., 1997; Eaton et al., 1998; Moore et al., 2002; Somers and Clemente, 2002). For example, Ibuki and colleagues (1997) observed a marked reduction of GABAergic profiles in the rat lumbar spinal dorsal horn in laminae I–III following a sciatic nerve ligation, and Ralston and colleagues (1997) reported reductions in the GABAergic circuitry of the superficial dorsal horn of the rat following chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve. In these studies, the decrease in GABAergic circuitry was thought to explain the development of mechanical allodynia observed in these animals. It was proposed that reduced GABA inhibition decreases the modulation of incoming noxious signals, which results in an abnormally intense activation of dorsal horn neurons and an altered perception of the stimulus.

Increased GABAergic circuitry during an early postlesion period has only been shown as a transient effect. Castro-Lopes et al. (1992, 1994), for example, observed an increase of GABAir cells in the rat superficial dorsal horn following induced inflammation of the hind foot, but this persisted for only the first 5 postinjury weeks (Castro-Lopes et al., 1992) before returning to normal levels.

Studies of lesions at higher levels of the afferent pathway also generally point to a reduction of GABAir synapses or neuronal populations. After a lesion of the dorsal column nuclei, Ralston and colleagues (Ralston and Ralston, 1994; H.J. Ralston et al., 1996) showed a transneuronal reduction of GABA-ir inhibitory synapses in the thalamic VPLc nucleus in the macaque monkey. Using light microscopy, Rausell and colleagues (1992) also observed a reduction of GABAergic neuronal populations within the macaque thalamus more than a decade following an extensive dorsal rhizotomy.

In the present study, synaptic alterations in the spinal dorsal horn following a partial deafferentation of the central somatosensory pathway were examined, using a well-defined and discrete cervical dorsal rhizotomy in the monkey, which has been shown to result in the loss of all detectable cutaneous and proprioceptive input to digits 1–3 (Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000). We have previously shown that such injuries produce an initially severe deficit in digit/hand function in monkeys and that, over the first weeks and months, digit function recovers remarkably (Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005). Functional recovery appears to be mediated, at least in part, by the postinjury sprouting of spared primary afferents into the dorsal horn within the “lesion zone” (that region of the cord largely deafferented by the lesion). These spared afferents still innervate the impaired digits but are too sparse and functionally ineffective to allow sensorimotor function immediately postlesion (Darian-Smith, 2004). Our goal in this investigation was to determine what changes occur in the neuronal circuitry of the superficial dorsal horn, following a dorsal rhizotomy. Such changes have not been examined previously in the primate at the ultrastructural level. The focus of our analysis was on synaptic profiles within the superficial laminae I–III of the dorsal horn, because these layers are known to receive the major mechanoreceptor and nociceptor inputs from the affected digits (for reviews see Willis and Coggeshall, 2004; Morris et al., 2004; Darian-Smith, 2007, 2008).

Our major finding was both expected and seemingly contradictory to earlier reports. Here, we observed a highly significant increase in the inhibitory circuitry within the spinal dorsal horn up to 23 weeks following a cervical dorsal rhizotomy in the monkey.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental sequence and animals used

Two male macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) were used in this study (M406, 3.1 kg; M506, 3.3 kg). Monkeys were colony bred and approximately 3 years of age. They were housed at the Stanford Animal Facility, in adapted four-unit cages per monkey (64 × 60 × 77 dwh per unit). All procedures were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and protocols were in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Each monkey underwent a laminectomy and a craniotomy. They first received a cervical dorsal rootlet lesion as described below and in earlier papers (Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2006). At either 12 weeks (M406) or 15 weeks (M506) following the lesion, they underwent a bilateral craniotomy over the primary somatosensory cortex. The region of digit representation was mapped electrophysiologically as described below and elsewhere (see Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000; Darian-Smith, 2004; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005, 2006), to identify the region of cortical reactivation. M406 survived for 4 more weeks and M506 for 8 more weeks before the experiments were terminated.

Behavioral testing

Both monkeys were tested behaviorally for their ability to perform a reach-grasp-retrieval task requiring cutaneous feedback. This form of assessment was described in detail in an earlier paper (Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2006). Because it was not possible to obtain data systematically from these monkeys, their behavior is not described in this paper, other than to say that both monkeys exhibited a typical deficit and recovery pattern of performance (see Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005). Both had a significant postlesion deficit in their ability to perform a precision grip task requiring cutaneous feedback from the pads of the affected digits for 5–6 weeks postlesion, but they then recovered to near-prelesion performance levels by 9 weeks postlesion. Their recovery of cutaneous sensibility was also demonstrated during electrophysiological mapping of their primary somatosensory cortex (see below). We did not observe postlesion hypersensitivity to cutaneous stimuli in these monkeys, which is consistent with earlier observations.

Surgery and perfusion

Anesthesia was induced with ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg) prior to surgery and then maintained for the duration of the procedure with gaseous isoflurane (~1– 1.5%)/O2 and a standard open-circuit anesthetic machine. Atropine sulfate (i.m., 0.04 mg/kg) and cefazolin (i.v., 20 mg/kg) were given preoperatively.

Making the laminectomy and dorsal rootlet lesion

To map cutaneous receptive fields of axons in dorsal rootlets at 12 and 15 weeks following the DRL, the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord was exposed with a laminectomy, and the dura mater was resected to expose the dorsal rootlets (segments C5 through T1). A digital photograph was taken of the exposed segments, and each rootlet was identified on the photograph as recordings were made (see Fig. 1). Low-impedance tungsten microelectrodes (1–1.5 mΩ at 1 kHz) were lowered directly into each rootlet (diameter ~0.3 mm), and single and small multiunit extracellular recordings were obtained from axons at different depths and rostrocaudal locations. Ten or more cutaneous mechanoreceptive fields (RFs) were mapped within each rootlet, to create what we call a “microdermatome” map of the hand. A fine camel hair brush and Von Frey hairs were used to map cutaneous and proprioceptive RFs on the digits and hand. Cutaneous RFs were defined as those units responsive to calibrated Von Frey hair stimulation of <2.0 g (see Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000). After mapping RFs for the digits, the rootlets that showed responses to cutaneous stimulation of the index finger, thumb, and middle fingers were identified and cut at two locations (to leave an ~2–3-mm gap in each fascicle).

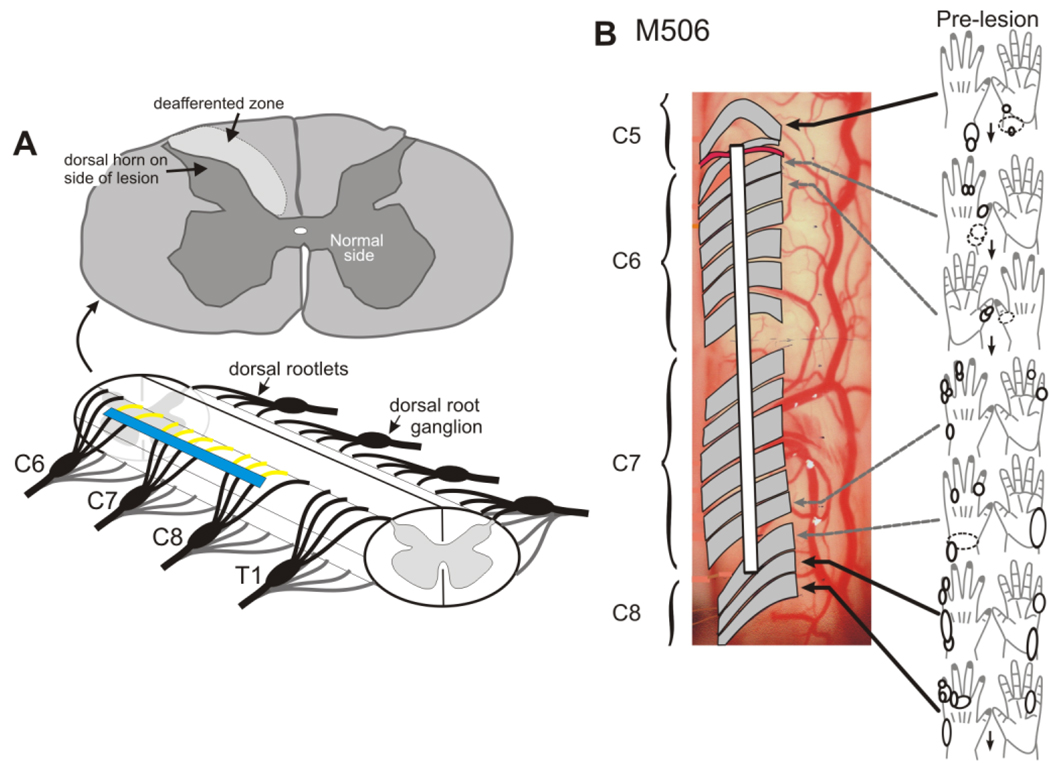

Figure 1.

Making a dorsal rootlet lesion. A shows a schematic of spinal cord segments C6–T1 and the approximate placement of a typical dorsal rootlet lesion (blue line). Rootlets within C5 through C8 may be involved in the lesion, depending on the individual monkey. The section above (C6) shows the region of deafferentation within the cuneate fasciculus and the location of BDA terminal labeling (arrow) within the dorsal horn (see Fig. 3A,B). B shows a partial “microdermatome” map for monkey M-506. Rootlets are shaded, as these are translucent in the photograph of the left cervical cord. Cutaneous and proprioceptive receptive fields are mapped onto cartoons of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hand, and the white line shows the extent of the lesion made in this monkey.

After we made the lesion, the incision was closed, and the fascia, muscle layers, and skin were carefully sutured in layers. An analgesic was administered postoperatively (butorphanol, 0.02 mg/kg), and the monkey returned to its cage for close postoperative observation. Both monkeys were up and alert within 1–2 hours of returning to their cage.

Recording in the somatosensory cortex

Recordings made in the somatosensory cortex were analyzed as described in earlier papers (Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000; Darian-Smith, 2004; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005, 2006). A craniotomy was used to expose the somatosensory cortex in the region of hand representation, and electrode (see above) penetrations were made along the rostral lip of the postcentral gyrus at the approximate border of areas 3b/1 (Fig. 2). Stimulus procedures equivalent to those used for dorsal rootlet recordings were also used for defining tactile RFs in area 3b/1.

Figure 2.

Maps of hand representation in cortical areas 3b/1 in the contralateral cortex in monkey M506, obtained by electrophysiological recordings, 15 weeks postlesion. Map shows the reemergence of detectable input from the digits initially experimentally deafferented following the cervical DRL. Inputs to the thumb (blue), index finger (red), and middle finger (green) were initially removed by the dorsal root lesion, and these regions would have been electrophysiologically inactive for approximately 3 months postoperatively. A similar map showing similar reactivation was obtained for M406 (for other examples see Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000; Darian-Smith, 2004; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005, 2006). Digit representations are coded in different colors, and the location of BDA injections, which were made into reactivated cortex to label corticospinal terminals, are shown by blue dots. Too few BDA-labeled synaptic terminals were identified ultrastructurally to analyze quantitatively. See Figure 3B and text.

Perfusion

At the termination of the experiment, monkeys were deeply anesthetized, given a lethal dose (i.v.) of sodium pentobarbital (0.44 ml/kg), and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, 1 liter, 20°C) followed by 2% paraformaldehyde, and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; 1 liter, 4°C). The brain and spinal cord were removed, postfixed in the same perfusate for 4–6 hours, and transferred to cold buffer overnight.

Light microscopy and BDA reaction

In monkey M506, the anterograde tracer biotin dextran amine (aqueous 10%; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was injected into the region of thumb index and middle finger representation in locations illustrated in Figure 2, and into similar regions on the contralateral side, using a constant-rate Hamilton syringe (20 µl) with attached micropipette. In an earlier experiment, not described in this paper, we injected BDA into a similar region on just one side and observed no terminal labeling within the ipsilateral dorsal horn. Ralston and Ralston (1985), using WGA-HRP, showed a small ipsilateral projection from the somatosensory cortex, but this appears to be tracer specific, and we have not observed this in animals used in other studies in which injections were made unilaterally (Darian-Smith, unpublished). It was therefore not considered an issue in the current study. Injections in M506 were all made using a micromanipulator and constant-rate Hamilton (1–20 µl) syringe. The syringe was back-filled, and a glass micropipette with 10–20 µm diameter tip was attached to its end and secured with 5-minute araldite. All injections (0.3 µl, 2 minutes) were made at an estimated depth of 800–1,000 µm.

To visualize the BDA, a series of sections (every 300 µm, 50 µm) was collected through the lesion zone and processed by a standard ABC technique (see Reiner et al., 2000), with diaminobenzidine (DAB)-glucose oxidase as the chromagen. The reaction product was stabilized for light microscopy by using DAB-nickel-ammonium sulfate.

Electron microscopy

Blocks of aldehyde-fixed spinal cord were cut on a vibratome at 50 µm in the transverse plane and collected through the spinal lesion zone, which included primarily segments C6 and C7 in both monkeys. The vibratome sections were placed in buffered 1% OsO4 for 2 hours, stained en bloc with uranyl acetate, dehydrated, and embedded in epon. Selected dorsal horn regions were trimmed from the embedded sections using adjacent Nissl-stained sections as a guide. The tract of Lissauer was always included in the sections to allow correct orientation. Selected regions of the dorsal horn were thin sectioned, mounted on grids, and stained with lead citrate.

EM immunocytochemistry

Postembedding immunocytochemistry was used to characterize GABA-immunoreactive (-ir) axon terminals and the dendrites of GABAergic interneurons (Ralston and Ralston, 1994; H.J. Ralston et al., 1996). Thin sections on grids were exposed to a primary affinity-isolated GABA antibody (Sigma), diluted 1:2,000, plus Triton-PBS, overnight. The anti-GABA antibody was developed in rabbit using GABA-BSA as the immunogen. The rabbit anti-GABA antibody showed positive binding with GABA in a dot blot assay and negative binding with BSA. Sections were rinsed in Triton-PBS and then exposed to a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 10-nm colloidal gold particles.

Methods of tissue sampling for electron microscopy (EM), and statistical analyses

Examination of thin sections (initially at ×5,000–10,000) was carried out by an observer who was blind to the particular experiment. Synaptic profiles were identified (see description of profile types below) and counted along 12 tracks (4 µm wide, with 10 µm between tracks parallel to the dorsal surface of the cord), across the superficial layers of the dorsal horn (medial-lateral). This superficial to deep sampling was used to identify any laminar specificity. Sections were sampled from cervical segments C5, C6, and C7 (depending on the monkey) within the lesion zone (the region deafferented by the lesion), and comparisons were made between equivalently located sections from the lesioned and nonlesioned sides. Synaptic profile numbers for each track were normalized with respect to the area of tissue examined, because this area differed per track, and were expressed per 100 µm2 of tissue (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Profile Counts Within the Spinal Dorsal Horn

| Animal & Cervical Segment |

Total profiles counted (number of profiles/100 µm2 for all tracks in each section) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side of Lesion |

Normal Side |

|||||||||

| Area µm2 |

R | F | F/GABAir | C | Area µm2 |

R | F | F/GABAir | C | |

| M406 | ||||||||||

| C5* | – | – | – | – | – | 23640 | 196 (0.83) | 155 (0.66) | 152 (0.64) | 102 (0.43) |

| C6 | 6350 | 89 = (1.4/100 µm2) | 102 (1.6) | 133 (2.1) | 12 (0.19) | 5950 | 76 (1.28) | 39 (0.66) | 48 (0.8) | 27 (0.46) |

| C6 | 11675 | 121 (1.04) | 130 (1.12) | 177 (1.52) | 4 (0.03) | 9615 | 76 (0.79) | 81 (0.84) | 43 (0.45) | 53 (0.55) |

| C7 | 8645 | 92 (1.06) | 117 (1.3) | 94 (1.09) | 4 (0.05) | 12295 | 149 (1.21) | 164 (1.33) | 58 (0.47) | 73 (0.6) |

| M506 | ||||||||||

| C5 | 9060 | 120 (1.3) | 132 (1.46) | 241 (2.67) | 11 (0.12) | 18960 | 162 (0.85) | 114 (0.60) | 66 (0.35) | 72 (0.38) |

| C6 | 8972 | 96 (1.1) | 154 (1.71) | 142 (1.6) | 5 (0.06) | 9655 | 82 (0.8) | 46 (0.48) | 43 (0.44) | 64 (0.66) |

| C7 | 9320 | 104 (1.1) | 99 (1.1) | 93 (1.0) | 5 (0.05) | 7660 | 95 (1.24) | 81 (1.05) | 41 (0.53) | 31 (0.40) |

Profile counts summed for 12 tracks within the dorsal horn in each of the sections sampled.

Profile counts are expressed per 100 µm2, and are given in parentheses (count/µm2). For example, for the first entry for M406, C6, profile R, 89/6350 = 1.4/100 µm2

This section from rostral C5 (at the border of C4) in monkey M406, was used as an example of unaffected ’normal’ tissue from outside the lesion zone.

The lesion zone in this monkey did not extend into C5 on the side of the lesion, so this section was more than a segment distant to the lesion zone.

In comparing the ipsilateral with the contralateral dorsal horn, the assumption was made that the contralateral side was, for the purposes of the analysis, “normal.” In the macaque monkey, in contrast to the rat (Chung et al., 1989), primary afferent input to the dorsal horn is strictly unilateral, so the DRL in our monkeys did not directly remove input from the contralateral sample region. It therefore seemed reasonable to use these sections as controls. However, indirect effects to the contralateral dorsal horn circuitry cannot be ruled out. To test our assumption, data were also obtained from a section (in M406) on the side contralateral to the lesion, more than a segment rostral (>4 mm) to the lesion zone in this animal. The data obtained from this section (see Tables 1 and 2 and Results) were compared (by ANOVA) with the other sections on the contralateral side, in the same monkey, M406, and in M506. No significant differences were observed between this section and the other contralateral sections in either monkey, which suggests that the contralateral superficial dorsal horn was not significantly different from normal, at least with respect to the characteristics examined.

TABLE 2.

Univariate Analysis of Variance for Different Profile Types: F and P Values

| R | F | F/GABAir | C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion vs. contralateral side | F = 4.09 | F = 38.89 | F = 135.03 | F = 276.79 |

| (combined data from M406 and M506) | P = 0.045 (<0.01) | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 |

| M406 vs. M506 (lesion vs. contralateral side) | F = 0.506 | F = 0.92 | F = 0.110 | F = 1.102 |

| P = 0.478 (<0.01) | 2 P = 0.339 (<0.01) | P = 0.741 (<0.01) | P = 0.296 (<0.01) | |

| M406, true control vs. lesion side | F = 8.798 | F = 245.75 | F = 701.24 | F = 1,027 |

| (M406 and M506) | P = 0.004 (>0.01)2 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 |

| M406, true control vs. lesion side (M406 only) | F = 4.846 | F = 19.510 | F = 43.268 | F = 232.349 |

| P = 0.031 (<0.01) | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | P = 0.000 (>0.01) 1 | |

| M406, true control vs. pseudo-control | F = 0.145 | F = 0.031 | F = 0.012 | F = 0.900 |

| sections (M406 only) | P = 0.705 (<0.01) | P = 0.861 (<0.01) | P = 0.915 (<0.01) | P = 0.346 (<0.01) |

P < 0.01.

The M406 control section R profile type was significantly different from R-type profiles on the lesion side. However, this was due to interanimal differences, insofar as the same control data compared with lesion data from the same animal (M406) does not show a significant difference in R profiles. See next row.

“True” control = a section in M406 on the side contralateral to the lesion that was more than one segment and > 4mmrostral to the lesion zone. “Pseudo-”control sections refer to the dorsal horn sections contralateral to the lesion side that paired dorsal horn sections on the side of the lesion inside the lesion zone.

In total, 4,666 profiles were counted (M506, 2,277; M406, 2,389). Univariate ANOVAs were used to compare profile counts between the two sides of the cord, between segments, and between animals. Paired-sample (two-tailed) t-tests were also used to compare track numbers (to examine laminar specificity), in which track 1 (located most superficially) on the lesion side was paired with track 1 on the contralateral side, track 2 with track 2, and so forth for each of the 12 tracks though the superficial dorsal horn. To correct for possible bias associated with tissue shrinkage on the side of the lesion, counts of each synaptic element (i.e., R, F, F-GABA, C; see below) were also represented as a proportion of the total profile count for each track summed across each pair of sections. Mean proportions (n = 3 section pairs per animal) of each profile type (see below) were plotted for each of the 12 tracks (see Fig. 7).

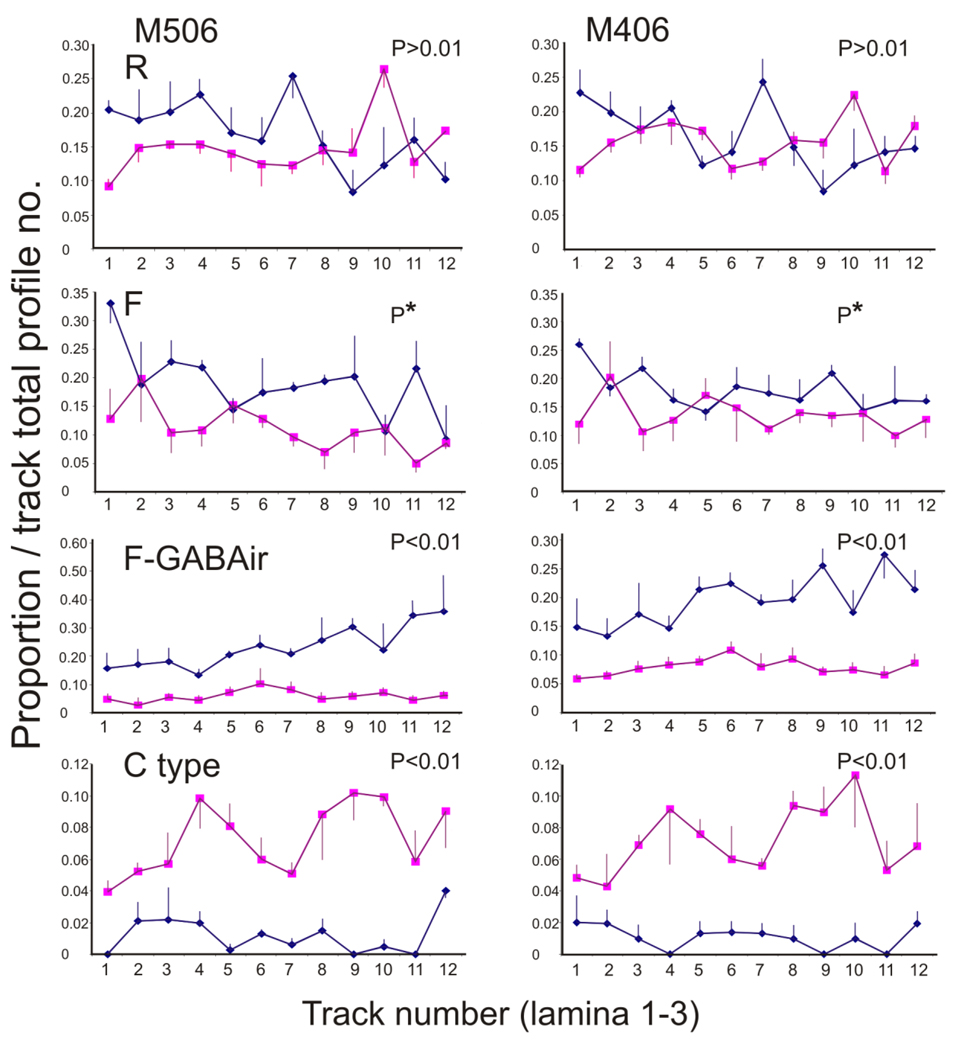

Figure 7.

Profiles showing the proportion of synaptic elements/total profiles in each track (1–12) through the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn in the two monkeys used in the current study. Proportions shown are mean values for all sections through segments C5–C7 in M506 and C6–C7 in M406. Data from the side of the lesion (lozenges) are directly compared with data from the nonlesioned side (squares), and paired-sample t-tests were used to determine the statistical differences in elemental profile proportions on the two sides of the cord. P values and distribution profiles are given for data sets and indicate a similar profile distribution pattern across the two monkeys. P*: Although F profile proportions were significantly greater on the side of the lesion overall, this was not consistently the case for all section pairs. Only two of three section pairs in M506 and one of three section pairs in M406 showed significantly more F profiles on the side of the lesion. These data indicate that primary afferent terminals decrease dramatically, whereas inhibitory (particularly GABAergic) profiles increase significantly on the side of the lesion during the early months following a cervical dorsal root lesion. See text for additional details of synaptic changes.

Several synaptic profile types were identified within each tissue section as described below and in previous studies (Ralston and Ralston, 1979a, 1985; for detailed descriptions of profile types see H.J. Ralston et al., 1996), and each was quantified (see Table 1). The character of postsynaptic densities along with the morphology of presynaptic vesicles was used to identify synaptic contacts. These observations were used to categorize the synaptic profile type. Each profile was counted rather than the number of synaptic contacts made by the profile.

To determine whether any of the differences in inhibitory synaptic populations (F types; see below) that we observed were due to actual changes in the numbers of F profiles, and not merely to changes in the size of the profiles, we estimated their numerical density by using the size-frequency method (DeFelipe et al., 1999). The analysis was carried out by examining all F profiles making axodendritic contacts that were observed in a total of 40 nonoverlapping electron micrographs from the lesion and the normal dorsal horn of C-6 of monkey M406. The micrographs sampled superficial (within 100 µm of the dorsal column white matter), intermediate (500–1000 µm deep), and deep (about 1,500 µm below the white matter) regions of the dorsal horn. The images were from negatives photographed at ×10,000 and printed to yield a final magnification of ×25,000. The area in which the counts were made was recorded, and the length of the postsynaptic membrane densities measured at the site of synaptic apposition between F profiles and dendritic structures (see Fig. 5A3 for a typical postsynaptic density used for these measurements). The numbers of F profiles per unit volume were then estimated using the formula Nv = NA/d, in which NA is the number of F profiles (those that were GABA-ir and those that were not) per unit area (100 µm2) and d is the average length of the synaptic densities (in micrometers). The results from the deafferented and nondeafferented sides were compared.

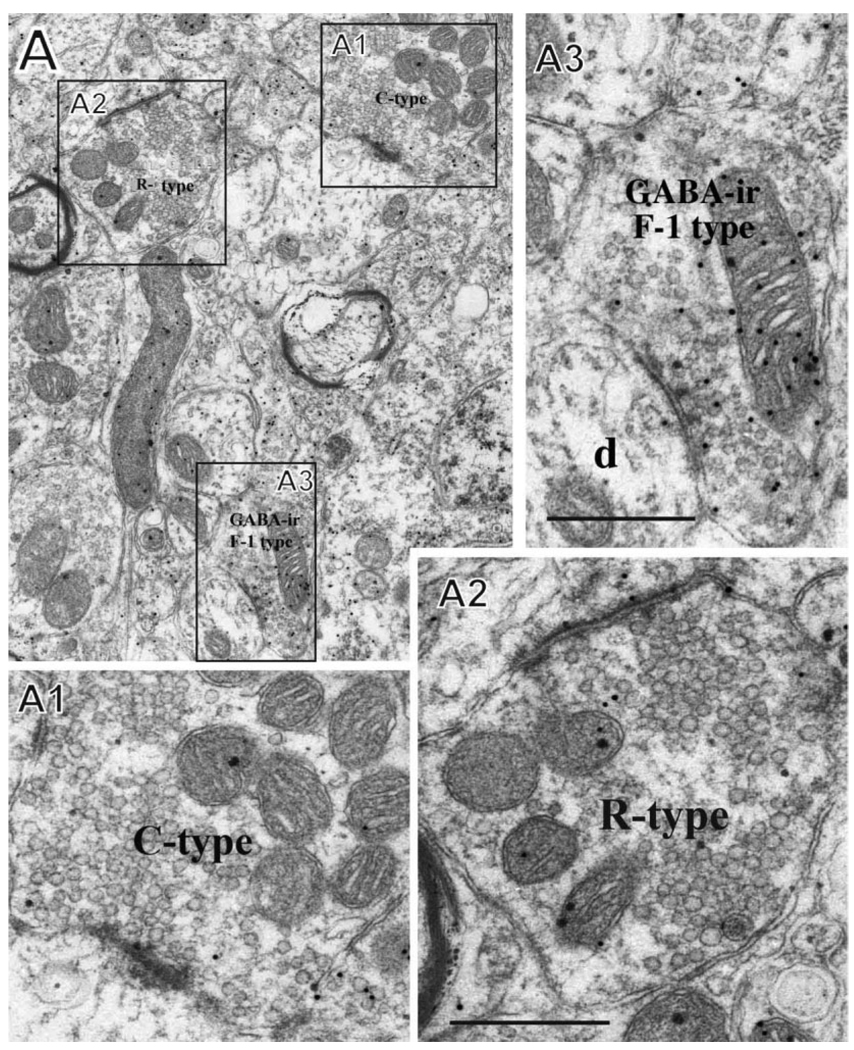

Figure 5.

A: Examples of C-type, F-1-type, and R-type profiles. A1 shows a C-type primary afferent terminal synapsing with a dendrite (an axodendritic profile). A2 shows an R-type terminal with a large synaptic profile and uniform round vesicles typical of an excitatory neuron, and A3 shows a presumed axon (F-1) terminal with pleiomorphic vesicles that is GABA-ir (labeled with immunogold). The F-1 profile contacts a dendritic spine (d). The section is from lamina II in the normal dorsal horn (C-6) in monkey M406. Scale bars = 0.5 µm.

Profile types

R types are synaptic profiles with round vesicles. These are presumed to be excitatory and probably originate from sources other than dorsal root afferents, because their numbers do not change significantly following dorsal rhizotomy. R-type profiles are distinguishable from C-type profiles (below) by having a single, large synaptic contact rather than contacting multiple postsynaptic structures (e.g., compare Figs. 4A1,A2 and 5A1,A2).

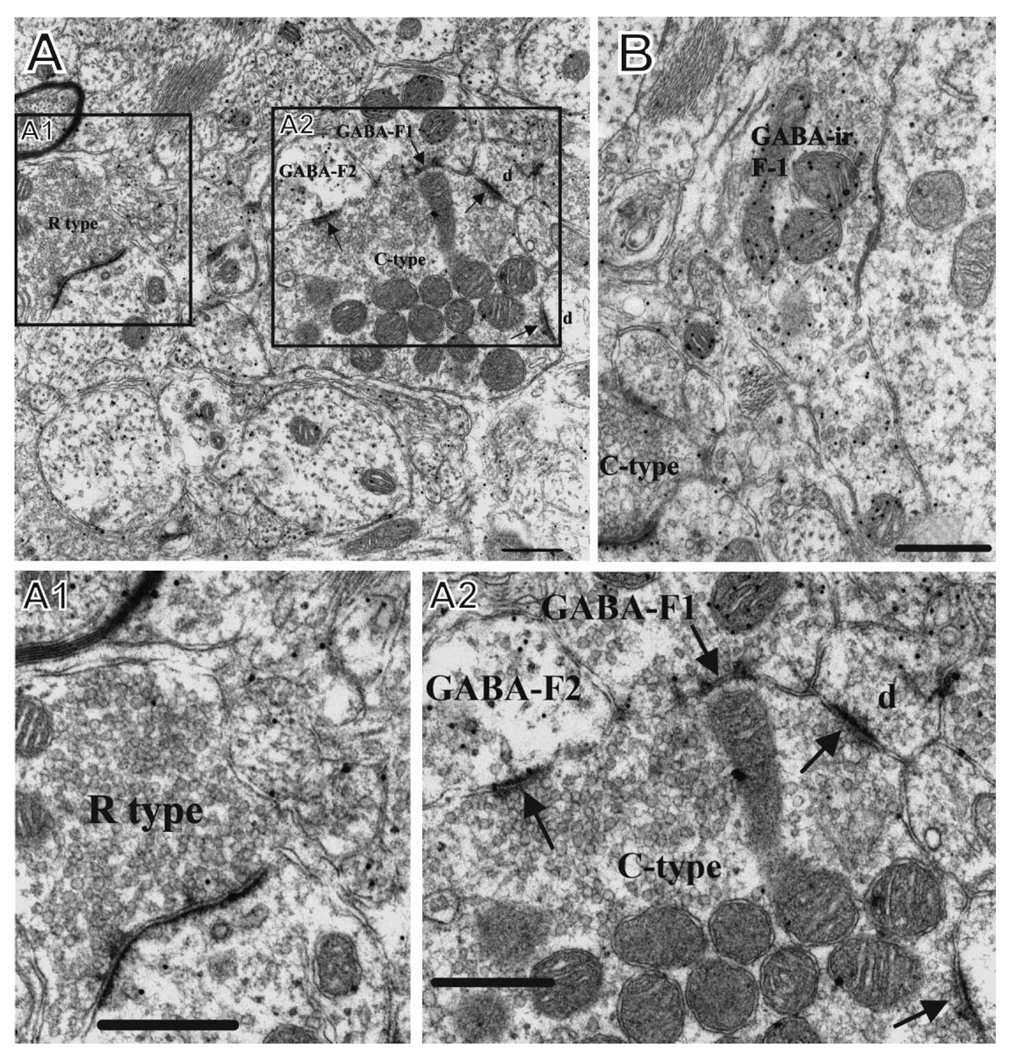

Figure 4.

A,B: Ultramicrographs in normal superficial dorsal horn illustrating examples of the different synaptic elements quantified in the current study. A1 shows a presumed excitatory R-type profile (with round synaptic vesicles) in lamina 1 in the normal dorsal horn (C-6) in M406. A2 shows a C-type axon terminal, characteristic of primary afferent fibers, that is engaged in multiple synaptic contacts. It is postsynaptic to a GABA-ir profile (GABA-F1) that is a presumed axon terminal and is presynaptic to GABA-F2, a presumed presynaptic dendrite of a GABAergic interneuron. It also contacts dendritic spines (d). B shows a GABA-ir profile (GABA-ir-F1) that synapses upon a neuronal cell body. A portion of a presumed primary afferent axon (C-type) contacts a GABAergic dendrite of an interneuron. The section is from lamina II in the normal dorsal horn (C-6) in M406. Scale bars = 0.5 µm.

F types are synaptic profiles with pleomorphic-flattened vesicles. These are presumed to be inhibitory and may be glycinergic or GABAergic. F-GABA type are profiles with pleomorphic-flattened vesicles that are immunoreactive for GABA.

C type are the terminals of primary afferent axons, which are large profiles (>1 µm diameter), contain round vesicles, and often form multiple synaptic contacts with dendritic shafts and spines of dorsal horn neurons. Dense-cored vesicles (DCV) are mostly primary afferents and have been shown in other studies to contain various peptide neurotransmitters. PSD are presynaptic dendrites of interneurons and are thought to be inhibitory.

Photomicrograph production

Photomicographs presented in the figures were originally scanned from 4-in.×5-in. negatives and downloaded as high-resolution TIF images to CorelDraw X3, in which they were cropped, arranged, and labeled.

RESULTS

Both monkeys received a dorsal rootlet lesion as described above. Figure 1 illustrates a part of the microdermatome map made in M506 in order to make the lesion. As illustrated for M506, rootlets spanning ~2.5 spinal segments were cut in each monkey to remove electrophysiologically detectable cutaneous and proprioceptive input from the thumb, index finger, and middle finger. This involved a total of 14 rootlets spanning C5–C8 in both monkeys (see other examples in earlier papers: Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000; Darian-Smith, 2004; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005, 2006).

Each monkey underwent a bilateral craniotomy at either 12 weeks (M406) or 15 weeks (M506) following the DRL to document the extent of reorganization in the primary somatosensory cortex. In the case of M506, injections of BDA were also made at this time into the region of reorganization, or the equivalent on the side ipsilateral to the lesion, to label corticospinal terminals within the spinal dorsal horn that originated from this cortical region. Figure 2 shows the resulting receptive field (RF) map of hand representation in the contralateral somatosensory cortex (areas 3b/1). As has been shown in previous studies (Darian-Smith and Brown, 2000; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2005, 2006), RFs were mapped on the initially deafferented digits (D1–3) at 3 and 4.5 months postlesion, indicating that the mechanisms mediating “cortical reactivation” had occurred within the spinal dorsal horn and at higher levels by this time (Darian-Smith, 2004; Darian-Smith and Ciferri, 2006).

Light microscopy

BDA terminal labeling was present at the light microscopic level within the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn on both sides of the cervical cord. Figure 3A shows an example of this in a semithin section from the lesioned side of C-7. The distribution of labeled terminals was mapped on the two sides throughout the lesion zone for a separate study and the distribution pattern found to be typical for injections made into the somatosensory cortex. Less labeling (~10–15% by distribution volume) was observed on the side of the lesion (Darian-Smith, unpublished).

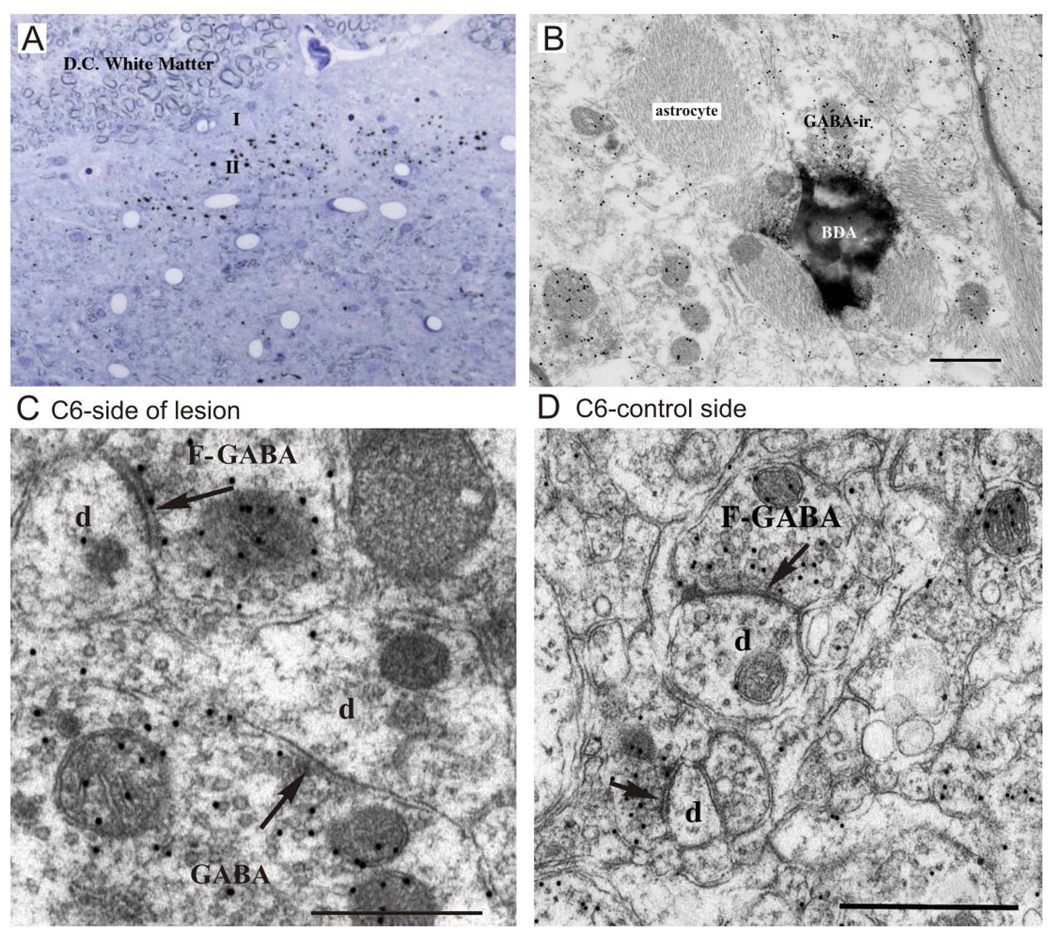

Figure 3.

A,B: Examples of BDA corticospinal labeling (black dots) in a semithin and ultrathin section within the deafferented superficial dorsal horn (C-7). A contains numerous BDA-labeled axons and terminals following injection of the tracer into the contralateral somatosensory cortex. B shows an example of a BDA-labeled axon terminal (in lamina II) from the same tissue. The labeled terminal is postsynaptic to a GABA-ir terminal (GABA-F2) that is presumed to be a presynaptic dendrite of a GABAergic interneuron. A GABA-ir F-1 profile is also shown (lower left). The abundant reactive astroglial filamentous processes are evident. C,D: Electron micrographs of GABAergic terminals (colloidal gold immunolabeling) within the deprived (C) and “normal” (D) dorsal horn in monkey M406 that had received a DRL 4 months earlier. In C, GABA-ir terminals make synaptic contact (arrows) with large and small dendritic profiles (d); in D, two GABA-ir F presynaptic profiles contact small dendritic structures (d). The difference between the number of immunogold particles overlying the immunoreactive and the nonimmunoreactive profiles is evident. Images like these were used to obtain counts of synaptic profiles in this study. Scale bars = 0.5 µm.

Electron microscopy

Thin sections from each of 12 vibratome sections were used to examine synaptic changes (seven sections from M406, including a “control” section outside the lesion zone, and six from M506). Sections on the side of the lesion were matched with tissue sections at an equivalent rostrocaudal level on the contralateral side. Profiles were identified and counted along 12 tracks (4-µm wide, spaced at 10-µm intervals and running parallel to the white matter) and recorded on a spreadsheet. In total 4,666 profiles (not including PSD and DCV profiles, which totaled only 122 for both animals) were counted in the two monkeys (M506 2,277; M406, 2,389).

Table 1 shows total area of tissue summed across all tracks, and total numbers of elemental profiles counted and summed across tracks per section. The number of profiles calculated per 100 µm2 is given in parentheses for each section. Data are shown only for the more commonly observed profile types (R, F, F/GABAir, and C). PSDs and DCV profiles were typically fewer, and, because numbers were negligible in M406, they were counted only in M506.

Corticospinal terminals

Figure 3A,B shows BDA-labeled corticospinal terminals from M506 at LM and EM levels. Corticospinal terminal distributions originating from the reorganized and normal S1 cortex (D1–D3 region) were observed within the superficial dorsal horn through the lesion zone. A series of sections was mapped through the lesion zone as part of a separate study. Distributions on the “normal” side were similar to those reported in previous studies (Ralston and Ralston, 1979a), and on the side of the lesion they were more sparsely distributed in the superficial laminae and medial deeper laminae. Despite the presence of reaction product in many sections at the light level (see Fig. 3A), identifying synaptic profiles in ultrathin sections at higher magnifications proved to be difficult. Even so, several interesting observations were made in sections on the side of the lesion.

Figure 3B shows one of several examples of a BDA-labeled axon terminal in lamina II. This terminal is postsynaptic to a GABA-ir terminal, which is presumed to be a presynaptic dendrite of a GABAergic interneuron. This makes the corticospinal synaptic profile dendroaxonal, whereby the corticospinal terminal receives direct interneuronal inhibition. This is a new finding, insofar as this was not described in an earlier study of corticospinal connections in the macaque monkey (Ralston and Ralston, 1985).

Synaptic profiles

Figures 3–6 illustrate typical examples of each of the major profile types quantified. Round, presumed excitatory profiles (Figs. 4A1, 5A2, 6) were relatively abundant throughout tissue sections and were not statistically different on the two sides following the lesion (see Table 1 for total number counts, Table 2 for univariate ANOVA, where P > 0.01; Fig. 7). These profiles may belong to any of the excitatory neuronal populations providing input to this area other than primary afferents (e.g., corticospinal, propriospinal, reticulospinal, rubrospinal). In contrast, primary afferent C terminals (Figs. 4A2, 5A1), identified as having large, round, clear vesicles and smaller but more numerous synaptic profiles (compared with R profiles), were significantly reduced on the side of the lesion (by a factor of 6, to ~16%) compared with the contralateral side, as was expected with the deafferentation produced by the dorsal rhizotomy (see Table 2 for ANOVA, P < 0.01).

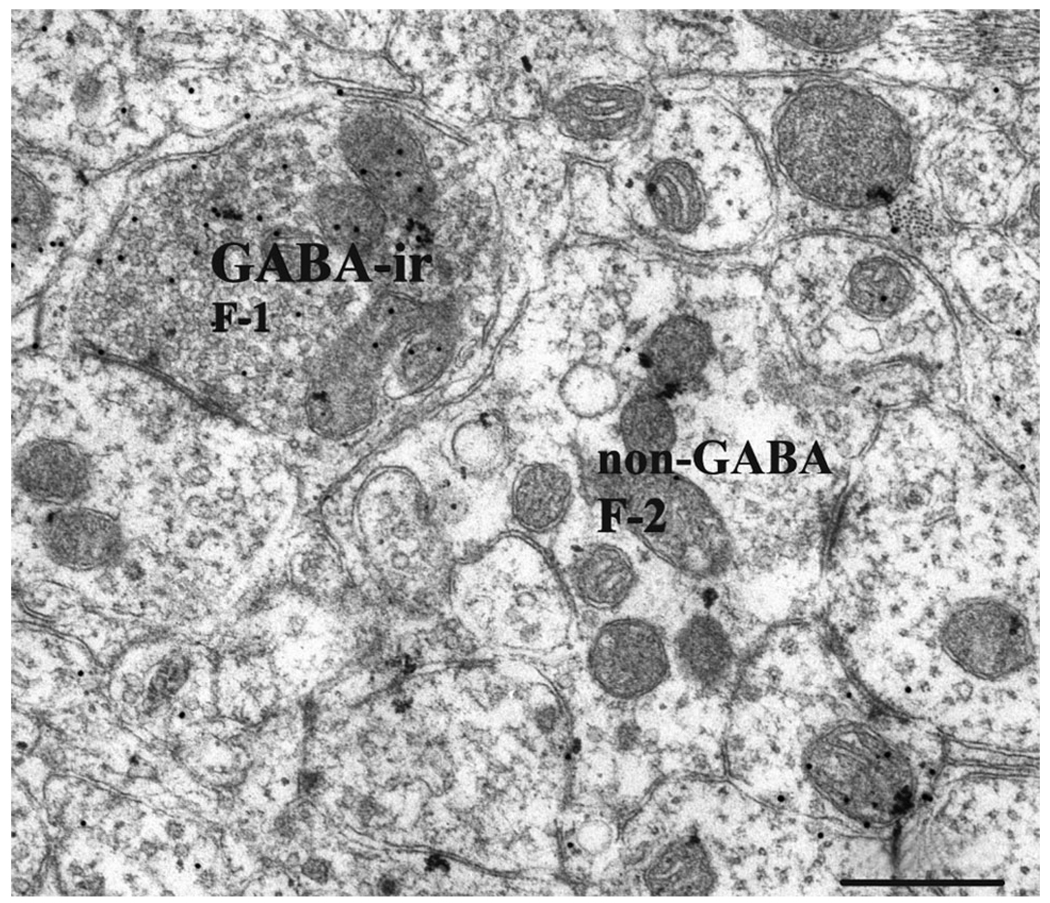

Figure 6.

Examples of F-1, F-2, and R profiles in lamina II in the normal dorsal horn in monkey M406 (C6). A GABA-ir F-1 profile (presumed axon terminal) synapses with a dendrite (upper left). The non-GABA-ir F-2 profile shown may be a presynaptic dendrite of a glycinergic interneuron. Scale bar = 0.5 µm.

Quantification of the F profiles (some being GABAir, others not), which are presumed inhibitory based on previous studies (Ralston et al., 1997), revealed more surprising results. F-1 (presumed axon terminal; Figs. 3C,D, 4B, 5A3, 6) and F-2 (presumed presynaptic dendritic; Fig. 4A2) profiles were counted separately in four sections (in M506, two on the lesion and two on the normal side) and occurred at an equal ratio (1:1) in all sections. For this reason, all F-1 and F-2 profiles were combined as one F category in these and the remaining sections, with the assumption that counts were approximately half axonal and half dendritic. When non-GABA-ir F profiles were compared between the lesioned and nonlesioned sides of the cord, these profiles were found to be more than 1.7 times more prevalent on the side of the lesion compared with the nonlesioned side (see Table 1, Fig. 7). The ANOVA reflected this (P < 0.01; Table 2). Even more striking were the F/GABAir profiles, which were proportionately 3.2 times more common on the side of the lesion than on the nonlesioned side. Again, the ANOVA reflected this (where P < 0.01; Table 2).

To determine whether the changes in F populations that we observed might have been due to changes in the size of the F profiles, we used the size-frequency method (DeFelipe et al., 1999) to estimate the numbers of F profiles per unit volume on the experimental and control sides of the dorsal horn (in total 133 F profiles were counted). The results were as follows: Normal: non-GABAir profiles were estimated at 2.21 profiles per 1,000 µm3 and GABA-ir profiles were estimated at 1.17 profiles/1,000 µm3; lesion: non-GABA-ir profiles were 3.40 profiles/1,000 µm3 and GABAir profiles were estimated at 4.79 profiles per 1,000 µm3. The results confirm the counts made per unit area: there was a significant increase in the numbers of F profiles (both GABA-ir and non-GABA staining) in the deafferented compared with the normal dorsal horn.

Figure 7 also clearly illustrates these differences. Profiles are expressed in terms of the proportion of each profile type/total profiles summed on the two sides of the cord (per track). Expressing profiles as a proportion of the total profile number, rather than as a number per 100 µm2 (calculated independently on the two sides), reduced potential bias on the side of the lesion resulting from tissue shrinkage. However, it should be noted that, when the area and volume of the dorsal horn were calculated from 14 sequential sections (spanning 9.92 mm, section thickness = 40 µm) taken through the lesion zone in M506, no statistical difference was found between the two sides. The volume of the dorsal horn was 6.78 ± 0.15mm3 on the side of the lesion and 6.81 ± 0.16 mm3 on the contralateral side. The dorsal horn was distorted in shape on the side of the lesion, but this did not translate to measurable atrophy (at this postoperative period) on the side of the lesion. This suggests that overall tissue shrinkage did not play a significant role in the differences observed. In addition, and importantly, there was no significant difference in R profiles in any of the section pairs (Tables 1, 2). This also indicates that the increase in inhibitory profiles could not be primarily attributed to shrinkage. Despite these reassurances, our data did not take into account the possibility of shrinkage of specific types of synapse or profile, which could affect the frequency with which they could be sampled. However, a 3.2-fold increase of GABAir profiles on the side of the lesion would be difficult to explain in terms of an enlargement of this specific profile type, and an unusual morphology was not observed on the side of the lesion, for any of the profile types.

The data sets illustrated in Figure 7 (dorsal to ventral track numbers) were surprisingly similar across the two animals, and, although the sample size is too small to be conclusive, these similarities also suggest that there may be laminar differences in the synaptic distributions. This would not be surprising, considering the different cellular populations within laminae I–III (Willis and Coggeshall, 2004). Signs of Wallerian degeneration were typically not observed within the dorsal horn but were present in the dorsal column white matter.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that, at 4–6 months following a restricted DRL in the macaque monkey, there was a major change to the synaptic circuitry in the superficial dorsal horn. As anticipated, there was a significant drop in the numbers of C-type profiles (primary afferents) on the side of the lesion (P < 0.005), which is directly associated with the deafferentation. What was surprising, however, was the substantial increase in the number of GABAergic profiles observed in the dorsal horn on the side of the lesion (P < 0.005).

A potential confounding factor was the possibility that there was an increase in the size of the F inhibitory profiles, which would increase the likelihood of detecting that profile type in individual micrographs. Accordingly, we estimated the number of F profiles per unit volume by using the size-frequency method. This technique has been shown to be more efficient and easier to apply than the dissector method (DeFelipe et al., 1999) and to be of comparable accuracy when used for a study such as the present one, in which synaptic populations are being compared (in normal and deafferented dorsal horn) rather than the absolute number of a given type of profile in a particular specimen being the goal (Guillery and Herrup, 1997). The results of the size-frequency analysis were in keeping with the counts based on numbers of F profiles per unit area. Both methods demonstrated that there is a significant increase in the numbers of inhibitory synapses (F profiles) in deafferented dorsal horn compared with the nondeafferented side.

A significant increase in the numbers of non-GABAergic presumed inhibitory F profiles was also observed on the side of the lesion in 50% of the section pairs, which suggests a general increase of the inhibitory circuitry, regardless of the neurotransmitter (e.g., GABA or glycine). In contrast to the rodent, the primate is not known to have colocalization of GABA and glycine in inhibitory boutons in the dorsal horn (Todd, 1996; Watson et al., 2002). No changes were observed in the numbers of other presumed excitatory synapses, although these data tell us nothing about changes to the weightings of these profiles or inputs from individual excitatory neuronal sources.

In the present study, dorsal rhizotomy of the monkey cervical spinal cord results in a significant increase of the GABAergic circuitry of the dorsal horn, in contrast to the effects of peripheral nerve and central lesions, which have been found to reduce the numbers of GABAergic elements (Ralston et al., 1997). Most studies of peripheral or central deafferentation have shown a decreased inhibition in the dorsal horn, and this typically correlates with a hypersensitivity to painful noxious or nonnoxious stimuli (D. Ralston et al., 1996; Moore et al., 2002; for review see Zeilhofer and Zeilhofer, 2008). In the present study, monkeys did not exhibit allodynia-like hypersensitivity to touch or pinprick in the partially deafferented digits at any time point following the lesion until the end of the study at 16 and 23 weeks. An absence of allodynia or pain-related symptoms and an elevated GABAergic neuronal population within the superficial dorsal horn is consistent with the view that reduced inhibition in the dorsal horn plays a role in neuropathic pain, by allowing the recruitment of surrounding neurons and the amplification and spread of abnormal neuronal activity and sensation as pain (Ralston et al., 1997; Yezierski, 2005).

An increased inhibition has not been demonstrated previously following a dorsal root or peripheral injury, although several studies of complete spinal transection in the rat have reported a transient up-regulation of the GABAergic inhibitory system (Tillakaratne et al., 2002). Tillakaratne and colleagues proposed that a transient increase in inhibition may serve a general role in preventing premature motoneuron activation following injury. Although not an equivalent injury to the DRL used in the present study, this does demonstrate a dynamic modulation of the inhibitory circuitry within the dorsal horn following different injuries.

What might account for this increase in GABAergic neurons following a dorsal rhizotomy is unclear. Nothing is known about the balance of excitation/inhibition within the spinal cord following a cervical dorsal rhizotomy or the functional role of an increased inhibition within the dorsal horn.

In addition to the loss of input following a deafferentation injury (be it a dorsal rhizotomy or a peripheral or central lesion), there are other postinjury parameters to consider that likely effect the projected outcome. Direct injury to the cord (e.g., following a dorsal column lesion) produces inflammatory responses and gliosis that can have a profound affect on the plasticity of the remaining intact neuronal populations within the spinal gray matter. Various factors (e.g., CSPGs, ephrins) are produced by activated astrocytes during the inflammatory process, and many of these are known to inhibit axonal growth, dendritic sprouting, and synaptogenesis (for reviews see Fawcett and Asher, 1999; Fouad and Tse, 2008). In contrast, permanent peripheral nerve injuries (e.g., as a result of amputation or nerve ligation) and dorsal root transections will not produce the same extensive inflammatory responses that are associated with central injuries. This means that the central cellular environment differs dramatically depending on the injury type, and such factors are likely to alter inhibitory and excitatory interactions in the dorsal horn during the postinjury weeks and months. Differing results in the literature may, at least in part, be explained by differences in the local spinal environment available postinjury, although this would not explain a decreased inhibition within the dorsal horn following a peripheral nerve injury.

Another factor that might help to explain discrepancies between our findings and those of others is the time course over which changes occur. Astrocytes and microglia, for example, change in their numbers and role during the postinjury period (Colburn et al., 1999). The GABAergic profiles may be similarly altered during reorganization of the circuitry postinjury until stability is achieved. Further work is needed to determine precise changes over time.

In our animals, the cervical dorsal rhizotomy permanently removed almost all sensory input from digits 1–3 to the dorsal horn. This removed the major excitatory input to the region (including Aδ, C, and Aβ inputs). Although most input is removed, we have previously shown that small numbers of spared primary afferents (which are initially functionally silent) sprout within the dorsal horn to establish new connections with postsynaptic target neurons within the dorsal horn (laminae I–V) that have lost their normal input. These additional connections are thought to amplify the transmission of salient input from the affected digits over 2–3 months to mediate the functional recovery observed in these animals. If there is a concomitant increase in the inhibitory circuitry in the dorsal horn, what populations are being inhibited? Does the loss of peripheral input lead to an abnormal amplification of excitatory input from elsewhere that has to be inhibited so that the small amount of spared peripheral input to the area can be amplified above threshold? One way to test this hypothesis would be to look at changes to the inhibitory circuitry in an animal with a more extensive dorsal rhizotomy, in which there is no sparing of input or recovery of function. One study that looked at the effects of an extensive dorsal rhizotomy more than a decade following the lesion indicated a reduction of GABAergic neuronal populations within the monkey thalamus, but the spinal circuitry was not examined (Rausell et al., 1992).

Recent studies in the monkey and rat in our laboratory provide evidence that adult neurogenesis occurs reactively within the dorsal horn following a cervical dorsal rhizotomy (Vessal et al., 2007). The newly formed neurons were observed primarily within the superficial laminae and were consistently immunopositive for GABAergic antibodies such as GABAA, GAD67, and the calcium-binding protein calbindin. These data suggest a potential increase in the numbers of inhibitory interneurons within the dorsal horn following a cervical dorsal rhizotomy. Although we are some way from linking these findings and the findings of the present study, neurogenesis of inhibitory interneurons does at least suggest one mechanism by which increased numbers of GABA-ir synaptic profiles might be observed within the lesion zone several months following the lesion.

Another possibility is that the increase in inhibitory profiles reflects local sprouting of preexisting inhibitory terminals, just as spared primary afferent terminals have been shown to sprout following a dorsal root lesion (Darian-Smith, 2004). However, although projection neuron populations have been shown to sprout following spinal injury in the primate, similar growth has not been demonstrated in local circuit inhibitory neurons of the dorsal horn.

How the findings of this study relate to functional outcome in the monkey is not clear, but an increase in inhibitory circuitry may help to structure and regulate newly formed connections during the postlesion period, as part of a long-term stabilization process. Studies that look at similar changes at 1 year following the initial lesion would help us to understand this. Future studies will be necessary to determine the role of an increased inhibition within the spinal dorsal horn following a cervical dorsal rhizotomy in the adult monkey.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Larry Ackerman for his technical help.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; Grant number: RO1NS048425 (to C.D.-S.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Castro-Lopes JM, Tavares I, Tolle TR, Coito A, Coimbra A. Increase in GABAergic cells and GABA levels in the spinal cord in unilateral inflammation of the hindlimb in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:296–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Lopes JM, Tavares I, Coimbra A. GABA decreases in the spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral neurectomy. Brain Res. 1993;620:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90167-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Lopes JM, Tolle TR, Pan B, Zieglgansberger W. Expression of GAD mRNA in spinal cord neurons of normal and monoarthritic rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;26:169–176. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K, McNeill DL, Hulsebosch CE, Coggeshall RE. Changes in dorsal horn synaptic disc numbers following unilateral dorsal rhizotomy. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:568–577. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colburn RW, Rickman AJ, DeLeo JA. The effect of site and type of nerve injury on spinal glial activation and neuropathic pain behavior. Exp Neurol. 1999;157:289–304. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C. Primary afferent terminal sprouting after a cervical dorsal rootlet section in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2004;470:134–150. doi: 10.1002/cne.11030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C. Monkey models of recovery of voluntary hand movement after spinal cord and dorsal root injury. ILAR. 2007;48:396–410. doi: 10.1093/ilar.48.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C. Plasticity of somatosensory function during learning, disease, and injury. San Diego: Elsevier, Academic Press; 2008. pp. 259–298. [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Brown S. Functional changes at periphery and cortex following dorsal root lesions in adult monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:476–481. doi: 10.1038/74852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Ciferri M. Loss and recovery of voluntary hand movements in the macaque following a cervical dorsal rhizotomy. J Comp Neurol. 2005;491:27–45. doi: 10.1002/cne.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darian-Smith C, Ciferri M. Cuneate nucleus reorganization following cervical dorsal rhizotomy in the macaque monkey: its role in the recovery of manual dexterity. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:552–565. doi: 10.1002/cne.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Marco P, Busturia I, Merchán-Pérez A. Estimation of the number of synapses in the cerebral cortex: methodological considerations. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:722–732. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.7.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton MJ, Plunkett JA, Karmally S, Martinez MA, Montanez K. Changes in GAD- and GABA-immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury and promotion of recovery by lumbar transplant of immortalized serotonergic precursors. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;16:57–72. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JW, Asher RA. The glial scar and central nervous system repair. Brain Res Bull. 1999;49:377–391. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouad K, Tse A. Adaptive changes in the injured spinal cord and their role in promoting functional recovery. Neurol Res. 2008;30:17–27. doi: 10.1179/016164107X251781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW, Herrup K. Quantification without pontification: choosing a method for counting objects in sectioned tissues. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:2–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970915)386:1<2::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibuki T, Hama AT, Wang XT, Pappas GD, Sagen J. Loss of GABA-immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn of rats with peripheral nerve injury and promotion of recovery by adrenal medullary grafts. Neuroscience. 1997;76:845–858. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, Kohno T, Karchewski LA, Scholz J, Baba H, Woolf CJ. Partial peripheral nerve injury promotes a selective loss of GABAergic inhibition in the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6724–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06724.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R, Cheunsuang O, Stewart A, Maxwell D. Spinal dorsal horn neurone targets for nociceptive primary afferents: do single neurone morphological characteristics suggest how nociceptive information is processed at the spinal level. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2004;46:173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston DD, Ralston HJ. The terminations of corticospinal tract axons in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1985;242:325–337. doi: 10.1002/cne.902420303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston D, Canchola S, Meng X-W, Ralston H. Changes in spinal cord inhibitory circuitry in an animal model of neuropathic pain; Proceedings of the free papers of the 7th International Symposium of The Pain Clinic; Istanbul, Turkey: Monduzzi Editori, Bologna, Italy; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston D, Behbehani S, Sehlhorst S, Meng X-W, Ralston H. Immunoreactivity in the dorsal horn of the rat following partial constriction of the sciatic nerve correlates with the behavioral manifestation of pain: a light and electron microscopic study. Progress in pain research and management. Seattle: I.A.S.P. Press; 1997. pp. 547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Ralston HJ, III, Ralston DD. The distribution of dorsal root axons in laminae I, II and III of the macaque spinal cord: a quantitative electron microscope study. J Comp Neurol. 1979a;184:643–684. doi: 10.1002/cne.901840404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston HJ, III, Ralston DD. Identification of dorsal root synaptic terminals on monkey ventral horn cells by electron microscopic autoradiography. J Neurocytol. 1979b;8:151–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01175558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston HJ, III, Ralston DD. Medial lemniscal and spinal projections to the macaque thalamus: an electon microscopic study of differing GABAergic circuitry serving thalamic somatosensory mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2485–2502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02485.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston HJ, III, Ohara PT, Meng XW, Wells J, Ralston DD. Transneuronal changes of the inhibitory circuitry in the macaque somatosensory thalamus following lesions of the dorsal column nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 1996;371:325–335. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960722)371:2<325::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausell E, Cusick CG, Taub E, Jones EG. Chronic deafferentation in monkeys differentially affect nocioceptive and nonnociceptive pathways distinguished by specific calciumbinding proteins and down-regulates g-aminobutyric acid type A receptors at thalamic levels. 1992;89:2571–2575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner A, Veenman CL, Medina L, Jiao Y, Del Mar N, Honig MG. Pathway tracing using biotinylated dextran amines. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers DL, Clemente FR. Dorsal horn synaptosomal content of aspartate, glutamate, glycine and GABA are differentially altered following chronic constriction injury to the rat sciatic nerve. Neurosci Lett. 2002;323:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillakaratne NJ, de Leon RD, Hoang TX, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, Tobin AJ. Use-dependent modulation of inhibitory capacity in the feline lumbar spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3130–3143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ. GABA and glycine in synaptic glomeruli of the rat spinal horn. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:2492–2408. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ, Sullivan AC. Light microscope study of the coexistence of GABA-like and glycine-like immunoreactivities in the spinal cord of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:496–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessal M, Aycock A, Garton MT, Ciferri M, Darian-Smith C. Adult neurogenesis in primate and rodent spinal cord: comparing a cervical dorsal rhizotomy with a dorsal column transection. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2777–2794. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AHD, Hughes DI, Bazzaz AA. Synaptic relationships between hair follicle afferents and neurons expressing GABA and glycine-like immunoreactivity in the spinal cord of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2002;452:367–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.10410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WD, Coggeshall RE. Sensory mechanisms of the spinal cord. Primary afferent neurons and the spinal dorsal horn. vol 1. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Lu P, McKay H, Bernot T, Keirstead H, Steward O, Gage F, Edgerton V, Tuszynski M. Endogenous neurogenesis replaces oligodendrocytes and astrocytes after primate spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2157–2166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4070-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yezierski RP. Spinal cord injury: a model of central neuropathy. Neurosignals. 2005;14:182–193. doi: 10.1159/000087657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilhofer HU, Zeilhofer UB. Spinal dis-inhibition in inflammatory pain. Neurosci Lett. 2008;437:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]