Abstract

Despite emerging evidence of the efficacy of psychotherapies for marijuana dependence, variability in outcome exists. This study examined the role of anxiety on treatment involvement and outcome. Four questions were examined: (1) is greater anxiety associated with greater impairment at baseline; (2) is baseline anxiety related to greater marijuana use and problems following treatment; (3) does adding cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to motivation enhancement therapy (MET) reduce anxiety relative to MET alone; (4) are reductions in anxiety associated with better outcomes. The sample was comprised of 450 marijuana dependent patients in the Marijuana Treatment Project. Marijuana use and anxiety were measured at pretreatment and 4- and 9-month follow-ups. At baseline, anxiety was linked to more marijuana-related problems. CBT was associated with less anxiety at follow-up compared to MET alone. Reductions in anxiety were related to less marijuana use. In fact, reduction in anxiety from baseline to 4-month follow-up was associated with less marijuana use at 9-months, but reduction in marijuana use did not predict subsequent anxiety. Data suggest anxiety is an important variable that deserves further attention in marijuana dependence treatment.

Keywords: Marijuana, Cannabis, Anxiety, Cognitive–Behavioral Treatment, Motivation Enhancement Therapy, Motivational Interviewing

1. Introduction

Marijuana remains the most commonly used illegal drug, but until recently, there were few data on the efficacy of treatment for marijuana dependence. Although a number of recent studies suggest behavioral therapies are efficacious in reducing the frequency of marijuana use and marijuana-related problems (Budney et al., 2000; Stephens et al., 2000; Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004; Budney et al., 2006; Carroll et al., 2006), there has been variability in outcome. Hence it is important to evaluate the role of co-occurring problems and symptoms on treatment involvement and outcome.

There is good reason to believe anxiety could impact marijuana treatment outcomes. Although the role of anxiety in marijuana treatment is largely unexplored, patients seeking treatment for marijuana problems report significantly elevated anxiety compared to non-patient samples (Copeland et al., 2001). High levels of anxiety among individuals with substance use is noteworthy because the co-occurrence of elevated anxiety and marijuana dependence may result in greater impairment than either condition independently (Buckner et al., 2008b). To illustrate, among patients seeking treatment for alcohol use disorders (AUD) in Project MATCH (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998), patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD) were more likely to have major depressive episodes, experience more severe alcohol dependence, and exhibit lower occupational status and less perceived peer social support than patients with AUD without SAD (Thevos et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 1999). Thus, individuals with higher levels of anxiety in marijuana treatment may similarly present with greater functional impairments which could have important implications for treatment.

Anxiety may also undermine treatment gains by serving to increase the risk of relapse. Among patients receiving treatment for marijuana dependence, history of anxiety disorder treatment is associated with reentry into marijuana treatment following marijuana treatment completion (Arendt et al., 2007). Marijuana users report using marijuana to cope with stress and anxiety (Ogborne et al., 2000; Hathaway, 2003) and relaxation or relief from tension is a commonly reported reason for and a commonly reported effect from marijuana use (Reilly et al., 1998; Copeland et al., 2001; Hathaway, 2003). In fact, marijuana users with elevated anxiety (e.g., social anxiety, anxiety sensitivity or fear of anxiety-related sensations) report using marijuana to cope with negative affect (Buckner et al., 2007; Zvolensky et al., 2009). Taken together, these data suggest that the elevated anxiety associated with withdrawal may increase risk of using marijuana to manage anxiety, thereby increasing relapse vulnerability.

To examine the role of anxiety in marijuana treatment, we used data from a large multisite randomized trial of treatments for marijuana treatment (Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004) in which 450 individuals were randomly assigned to one of three psychosocial treatment conditions: motivation enhancement therapy (MET) alone, combined cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and MET, and delayed treatment. The following research questions were addressed. First, how do marijuana users with elevated anxiety differ from those with less anxiety at the point of seeking treatment? Given data indicating that some anxiety states (e.g., social anxiety) tend to be associated with high rates of marijuana-related problems (but not greater frequency of marijuana use) (Buckner et al., 2007; Buckner and Schmidt, 2008, in press), we expected higher anxiety at baseline would be associated with higher levels of marijuana-related impairment but would be unrelated to marijuana use frequency. Second, how does elevated anxiety influence treatment engagement and outcome? We hypothesized that those with higher levels of baseline anxiety would have poorer marijuana use outcomes than those with less baseline anxiety.

Third, are different treatment approaches associated with greater reduction in anxiety? Although data suggest that interventions targeting motivation can be used with anxious patients to improve CBT adherence (Maltby and Tolin, 2005; Westra and Dozois, 2006; Buckner and Schmidt, 2009; Buckner, in press) and decrease substance use (Buckner et al., 2008a), these interventions in and of itself does not appear to reduce anxiety (Westra and Dozois, 2006). On the other hand, CBT for substance use disorders teaches skills to cope with withdrawal and manage negative affective states such as anxiety. As such, CBT for marijuana dependence was expected to reduce anxiety more so than MET alone.

Fourth, are reductions in anxiety during the course of treatment associated with better marijuana-related outcomes at follow-up? It was hypothesized that reductions in anxiety from baseline to 4-month follow-up would be related to better marijuana outcomes at 9-month follow-up. Finally, analyses were conducted for the entire sample and separately by sex given that sex differences in the relations between anxiety and marijuana use have been observed (Buckner et al., 2006a; Buckner et al., 2009).

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Data for the present study were from the Marijuana Treatment Project, a large multisite randomized trial of treatments for marijuana treatment (Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004). As described in more detail elsewhere (Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004), participants were recruited between May 1997 and August 1998 through local media, public service announcements, and flyers targeting adults interested in receiving free individual outpatient treatment to help them quit heavy marijuana use. The study was conducted at the University of Connecticut Department of Psychiatry, Farmington, Connecticut (n = 155); The Village South, Miami, Florida (n = 149); and Evergreen Treatment Services, Seattle, Washington (n = 146). A total of 1,211 interested callers were screened by telephone during the 16-month recruitment period. Participants were eligible if, at time of screening, they were 18 years of age or older, had a DSM-IV diagnosis of current marijuana dependence, and used marijuana on at least 40 of the past 90 days. Three collaborating sites collectively recruited 450 eligible participants (308 men, 142 women).

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: MET alone, combined CBT-MET, and delayed treatment. Randomization was conducted via an urn randomization (probabilistic balancing) computer program (Stout et al., 1994), which was used to maximize the probability that the treatment groups were comparable with regard to characteristics likely to affect treatment outcomes (i.e., occupational status, race, gender, age, education and marijuana problem severity). The groups did not differ on demographic variables or on severity of marijuana problems (see Stephens et al., 2002, for more detailed information regarding study randomization).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Substance use problems

All participants completed a baseline assessment session with trained research staff. During this session, participants signed an informed consent form and completed a series of structured interviews and self-report questionnaires. Diagnoses of alcohol and illicit substance use disorders1were obtained using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 1994). The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan et al., 1992) is a structured interview used to measure the severity of medical, employment, legal, alcohol and drug, and psychiatric problems. The Marijuana Problem Scale (MPS) (Stephens et al., 2000) is a self-report measure of 19 recent (previous 90 days) problems associated with marijuana use. At baseline, MPS scores ranged from 1 to 19 (M = 9.59, SD = 3.56).

2.2.2 Substance use

The timeline follow-back (TLFB) (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) interview was used to create variables of number of marijuana joints smoked per day, percentage of days substances were used (marijuana, alcohol, and other drugs), and number of weeks of marijuana abstinence. Past 90 day use was assessed at each assessment point. Both urine specimen results and collateral informant interview data indicated that participants did not appear to underreport their marijuana use. At baseline, past 90 day use ranged from 27–90 (M=79.50, SD=14.59) days of marijuana use.

2.2.3 Anxiety and depression

Anxiety was assessed via the state portion of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1983). The state portion has evidenced adequate internal consistency and sensitivity to change in adult samples (Barnes et al., 2002; van Minnen and Foa, 2006; Comer et al., 2008). At baseline, scores ranged from 20 to 75 (M = 39.63, SD = 11.82). Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1961), a self-report measure of depressive symptoms. At baseline, scores ranged from 0 to 37 (M = 11.42, SD = 7.57).

2.3 Treatment interventions

MET and CBT-MET interventions were similar to those used in previous studies (Stephens et al., 1994; Budney et al., 2000; Stephens et al., 2000). Both treatments promoted abstinence from marijuana as the treatment goal but were not dogmatic in this regard. Therapists encouraged participants with moderate use goals to see the advantages of initiating a period of complete abstinence before attempting controlled use, but continued to support attempts to reduce marijuana consumption if complete abstinence was rejected. The same therapists conducted both treatments at each site. Therapists received on-going supervision and were trained to follow detailed therapy manuals. Independent evaluators reviewed sample treatment sessions and determined that study therapists adhered closely to the treatment manuals.

2.3.1 MET alone

The MET condition was comprised of two 1-hour sessions scheduled 1 week and 5 weeks after randomization. MET is designed to resolve ambivalence and elicit motivation to change (Miller et al., 1992; Miller and Rollnick, 2002). The MET condition treatment sessions were separated by 1 month to allow participants time to make changes that could be discussed with the therapist at the second meeting. During the first session, the therapist reviewed and discussed a personal feedback report (PFR) to explore ambivalence and encourage discussion of strategies for change. The PFR included summaries of the client's recent marijuana use, problems, concerns, attitudes favoring and opposing change in marijuana use, and ratings of self-confidence about change. At the second session, efforts to reduce marijuana use were reviewed and adjustments in strategy were made as necessary. MET was used to address ambivalence as needed. Participants had the option of involving a significant other (e.g., spouse, partner, friend) during the second session.

2.3.2 CBT-MET

The CBT-MET condition consisted of nine sessions delivered over a 12-week period. This treatment included MET, case management, and CBT-based skill-building (Steinberg et al., 2002). The first eight sessions were scheduled weekly and began 1 week after baseline. Similar to the MET alone condition, the first two sessions were used to review the PRF and bolster motivation to change marijuana use. Two sessions of case management typically followed the MET sessions. During the case management sessions, the therapist and patient worked to problem-solve potential obstacles to marijuana abstinence as identified from baseline measures (e.g., ASI subscales).

The CBT component explored potential triggers or high-risk situations for marijuana use and helped patients develop coping skills to avoid marijuana use in those situations. The protocol included five core and five elective CBT modules adapted from prior treatment protocols for marijuana (Stephens et al., 2000) and other drugs (Kadden et al., 1992). The core sessions were (a) Understanding Marijuana Use Patterns, (b) Coping with Cravings and Urges to Use, (c) Managing Thoughts about Re-Starting Marijuana Use, (d) Problem Solving, and (e) Marijuana Refusal Skills. Five elective modules covered the following areas: Planning for Emergencies/Coping with a Lapse, Seemingly Irrelevant Decisions, Managing Negative Moods and Depression, Assertiveness, and Anger Management. Although the remaining five sessions were designated primarily for CBT, therapists were given latitude in deciding along with the client whether to cover all CBT modules, modify the order in which they were covered, and/or substitute certain electives for core modules. The ninth session was scheduled during Week 12 (4 weeks after the eighth session) to provide participants the opportunity to review change strategies with their therapists after a period without weekly contact. Participants had the option of involving a significant other in up to two sessions.

2.3.3 Delayed treatment

Participants in the delayed treatment condition (DTC) waited 4 months and then completed a second assessment. The DTC group also was assessed briefly by phone at 4 and 12 weeks post-randomization to check for possible clinical deterioration during the waiting period. No participants were referred to treatment or withdrew from the trial because of clinical deterioration. At the completion of the 4-month waiting period, DTC participants were allowed to initiate either of the two treatment protocols.

2.4 Follow-up procedures

Participants in both of the active treatment conditions were assessed 4 and 9 months after the start of treatment using relevant baseline assessment instruments. The DTC assessment was conducted at 4 months post-randomization. DTC participants were not assessed after the 4-month follow-up. Research assistants were not blinded to the participants’ experimental condition. The TLFB, ASI, and SCID (Cannabis Use Disorders section) were repeated at the 4- and 9-month in-person follow-ups, as were questionnaires assessing marijuana-related problems and anxiety. Participants were paid $50 for each of the 4- and 9-month follow-ups.

Retention rates at 4-month and 9-month follow-up assessments were 88.4% and 87.1% respectively. Specifically, at 4-months, retention rates were 92.6%, 87.7%, and 85.3% for the DTC, MET alone, and CBT-MET groups respectively. At 9-months, retention rates were 86.3% and 87.8% for the MET alone and CBT-MET groups respectively. Attrition did not differ as a function of condition and study completers did not differ from those who dropped out on gender, age, education, marijuana use, or dependence severity (Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004).

2.5 Data analysis

To examine whether level of self-reported anxiety resulted in greater marijuana-related impairment at pre-treatment, bivariate correlations were conducted. Bonferroni corrections were applied to control for Type I error (p < 0.05/18 or 0.003). To examine relations between pretreatment anxiety and post-treatment marijuana problems, hierarchical linear models were conducted on patients in the active treatment conditions to test the incremental predictive ability of pre-treatment anxiety on treatment outcome measures after controlling for site and treatment condition.

Repeated measures hierarchical linear model (HLM) analyses were performed to determine which treatment resulted in greatest reductions in anxiety. In the first model, treatment condition and site were between-participants factors, and the baseline and 4-month follow-up assessment points formed a within-participants factor, time. The covariate of depression was included as a random factor.2 Initial outcomes at the 4-month follow-up were evaluated with 3 (treatment) × 3 (site) × 2 (time) HLM analyses because the DTC condition was only available at 4-months. Significant interactions were followed by planned contrasts comparing means of the treatment conditions while controlling for the baseline value of the dependent variable. In the second model, change over time and maintenance of treatment gains for the two active treatments were evaluated across the baseline, 4-month follow-up, and 9-month follow-up assessments with 2 (treatment) × 3 (site) × 3 (time) HLM analyses. An intent-to-treat strategy was utilized such that all randomized participants were included in the appropriate analyses.

To assess whether change in anxiety during treatment was associated with marijuana outcomes, partial correlations were conducted to examine the relations between follow-up anxiety and marijuana variables after controlling for baseline levels of anxiety, depression,2 and each marijuana variable. Bonferroni corrections were applied to control for Type I error (p < 0.05/24 or 0.002).

3. Results

3.1 Relations between pre-treatment anxiety and baseline functioning

At baseline, anxiety between men (M = 39.05, SD = 11.52) and women (M = 40.91, SD = 12.43) did not significantly differ (r = 0.07, p = 0.13). Using the Bonferroni corrected p value (0.003), there was a trend for anxiety to be negatively correlated with years of education completed (r = −0.14, p = 0.004). Table 1 details the correlations between anxiety and psychiatric variables. Anxiety was positively significantly correlated with impairment in several areas: number of DSM-IV marijuana abuse and dependence symptoms, MPS, ASI-medical, ASI-drug, ASI-psychiatric, and depression. There was a trend (0.003< p < 0.05) for anxiety to also be related to: number of marijuana joints smoked per day (p = 0.018), % days used other drugs (p = 0.005), and ASI-employment (p = 0.013). Anxiety was unrelated to % days used marijuana, % days used alcohol, ASI-alcohol and ASI-legal scores.

Table 1.

Means, frequencies, and correlations between anxiety and psychiatric variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anxiety | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Depression | 0.66*** | ||||||||||||||

| 3. # marijuana abuse items1 | 0.17*** | 0.19*** | |||||||||||||

| 4. # marijuana dependence items1 | 0.16*** | 0.27*** | 0.33*** | ||||||||||||

| 5. Marijuana problems | 0.39*** | 0.44*** | 0.39*** | 0.47*** | |||||||||||

| 6. % days used marijuana | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.04 | ||||||||||

| 7. % days used alcohol1 | −0.05 | −0.11* | −0.01 | −0.10* | −0.12* | −0.01 | |||||||||

| 8. % days used other drugs1 | 0.13** | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.02 | ||||||||

| 9. # of joints /day1 | 0.11* | 0.23*** | 0.20*** | 0.30*** | 0.21*** | 0.21*** | −0.15*** | −0.02 | |||||||

| 10. ASI-medical | 0.20*** | 0.26*** | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.15*** | −0.05 | −0.12* | −0.01 | 0.18*** | ||||||

| 11. ASI-employment | 0.12* | 0.19*** | −0.11* | 0.10* | 0.12* | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.20*** | 0.15*** | |||||

| 12. ASI-alcohol | −0.06 | −0.10* | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.81*** | 0.03 | −0.18*** | −0.10* | −0.03 | ||||

| 13. ASI-drug | 0.24*** | 0.25*** | 0.18*** | 0.28*** | 0.27*** | 0.29*** | 0.22*** | 0.11* | 0.16*** | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.22*** | |||

| 14. ASI-legal | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.10* | 0.10* | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.28*** | 0.06 | 0.18*** | −0.07 | 0.03 | ||

| 15. ASI-psychiatric | 0.53*** | 0.57*** | 0.12** | 0.15*** | 0.30*** | 0.06 | −0.13** | 0.11* | 0.25*** | 0.26*** | 0.16*** | −0.11* | 0.20*** | 0.10* | |

| Mean (SD) | |||||||||||||||

| 39.63 | 11.42 | 2.08 | 5.61 | 9.59 | 0.88 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 2.89 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.15 | |

| (11.8) | (7.6) | (0.8) | (1.3) | (3.6) | (0.2) | (0.3) | (0.03) | (2.4) | (0.3) | (0.2) | (0.1) | (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.9) | |

Note. Depression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961), anxiety with the state portion of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1983), and marijuana problems with the Marijuana Problem Scale (Stephens et al., 2000). ASI = Anxiety Severity Index (McLellan et al0., 1992).

Past 90 days.

p < 0.003,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

Given the strong correlation between anxiety and depression, partial correlations were conducted to examine whether anxiety remained associated with measures of impairment after controlling for the variance attributable to BDI scores. Bonferroni corrections were applied (p < 0.05/14 or 0.004). Anxiety remained significantly associated with MPS (pr = 0.14, p = 0.003) and ASI-psychiatric (pr = 0.25, p < 0.001). There was a trend (.004< p < .05) for anxiety to be related to number of days used other drugs (pr = 0.11, p = 0.027) and ASI-drug (pr = 0.11, p = 0.026).

Next we examined these relations separately by sex, controlling for BDI. Among women, there was a trend (.004< p < .05) for anxiety to be related to MPS (pr = 0.19, p = 0.035) and ASI-psychiatric scores (pr = 0.21, p = 0.019). Among men, anxiety remained significantly correlated with ASI-psychiatric scores (pr = 0.27, p < 0.001), with a trending relation (.004< p < .05) to MPS (pr = 0.13, p = 0.034), ASI-drug (pr = 0.15, p = 0.010), and ASI-legal (pr = 0.13, p = 0.029).

3.2 Relations between pre-treatment anxiety and post-treatment marijuana problems

Among patients in the active treatment conditions, baseline anxiety was unrelated to number of sessions attended (β= −0.01, p = 0.82) and MPS at 4-month (β = 0.06, p = 0.32) and 9-month follow-up (β = 0.07, p = 0.28). Among women, there was a significant effect of anxiety on post-treatment marijuana problems such that after controlling for baseline MPS, treatment site, and treatment condition, baseline anxiety was associated with MPS scores at 4-month (β = 0.21, p = 0.055) and 9-month follow-up (β = 0.23, p = 0.040). Anxiety was not, however, related to number of sessions attended (β = −0.03, p = 0.68). Among men, baseline anxiety did not appear to have impacted post-treatment MPS at either follow-up assessment (β = −0.03, p = 0.68; β = −0.48, p = 0.63) or number of sessions attended (β = −0.10, p = 0.14).

3.3 Relations between treatment condition and post-treatment anxiety

Table 2 presents the baseline, 4-, and 9-month follow-up mean anxiety scores for each treatment condition as well as Treatment × Time interactions. The active treatment conditions differed as predicted at both 4- and 9-month follow-ups. The Treatment × Site × Time interaction was non-significant, F(4, 466.83) = 1.42, p = 0.23. Significant main effects of time (F(1, 467.94) = 57.37, p < 0.001) and treatment condition (F(2, 790.05) = 3.46, p = 0.03) were qualified by a significant Treatment × Time interaction. As evidenced on Table 2, at 4-months, individuals in the CBT-MET condition reported significantly less anxiety than the MET condition. Although the DTC reported less anxiety at baseline, this group did not significantly differ from either active treatment condition at 4-months. At 9-months, the Treatment × Site × Time interaction was non-significant, F(2, 549.78) = 1.35, p = 0.26. A significant main effect of time (F(1, 550.19) = 32.58, p < 0.001) was qualified by a significant Treatment × Time interaction. Specifically, the CBT-MET condition exhibited significantly less anxiety at 9-months compared to the MET condition.

Table 2.

Anxiety at Baseline, 4-Month and 9-Month Follow-Up by Treatment Condition for Entire Sample and Separately by Sex

| Delayed treatment | MET alone | CBT-MET | Treatment × Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | F | P | |

| Entire Sample | ||||||||

| Baseline | 34.93 | 0.83 | 37.88a | 0.87 | 37.28a | 0.83 | ||

| 4 months | 32.08 | 0.85 | 33.59 | 0.96 | 30.80b | 0.90 | 3.16 | 0.04 |

| 9 months | 34.36 | 0.92 | 30.64b | 0.86 | 3.82 | 0.05 | ||

Note. The delayed treatment condition was not assessed at the 9-month follow-up. MET = motivation enhancement therapy; CBT-MET = cognitive behavioral therapy plus motivation enhancement therapy. Depression included in each model as a random effects covariate. Means are estimated marginal means.

Means significantly different from delayed treatment condition (p<0.05).

Mean significantly different from MET alone condition (p<0.05).

3.4 Relationships between change in anxiety on post-treatment marijuana outcomes

Reductions in anxiety during the course of the study were associated with reductions in marijuana use and MPS at both 4- and 9-months (Table 3). This effect appears stronger for male than female patients. We also examined whether change in anxiety was associated with marijuana outcomes separately by treatment condition (Table 4). In the DTC, change in anxiety was not related to any marijuana outcome. In the MET condition, reductions in anxiety between baseline and 4-months were correlated with fewer marijuana problems Reductions in anxiety between baseline and 4-months were weakly correlated with fewer percentage of days smoked marijuana (p=0.002) and number of weeks of marijuana abstinence (p=0.005) at 4-months. Reductions in anxiety from baseline to 9-months were weakly correlated with fewer marijuana problems (p=0.005) and number of weeks of abstinence (p=0.005) at 9-months. In the CBT-MET condition, reductions in anxiety between baseline and 4-months were significantly correlated with number of times smoked per day at 4-month follow-up and weakly correlated with percentage of days smoked (p=0.004) and number of weeks abstinent (p=0.003) at 4-months. Further, reductions in anxiety between baseline and 9-months were weakly correlated with fewer marijuana problems (p=0.003), percent of days smoked (p=0.002), and number of weeks abstinent (p=0.003) at 9-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Partial Correlations of Anxiety with Marijuana-Related Outcome Measures Among Patients In Active Treatment Conditions

| Total N = 302 |

Women n = 99 |

Men n = 203 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Time | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety |

| Period | (4 months) | (9 months) | (4 months) | (9 months) | (4 months) | (9 months) | |

| Marijuana problems | 4 months | 0.27** | 0.21* | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.25* | 0.23* |

| 9 months | 0.27** | 0.29** | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.27* | 0.33** | |

| Times smoked per day | 4 months | 0.27** | 0.25** | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.26* | 0.29** |

| 9 months | 0.25** | 0.19* | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.33** | 0.21* | |

| % days smoked | 4 months | 0.30** | 0.26** | 0.31* | 0.14 | 0.29** | 0.32** |

| 9 months | 0.25** | 0.28** | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.22* | 0.29** | |

| # weeks abstinent | 4 months | −0.30** | −0.30** | −0.32* | −0.20 | −0.28** | −0.37** |

| 9 months | −0.27** | −0.30** | −0.29 | −0.33* | −0.28** | −0.29** | |

Note. Participants in the delayed treatment condition were excluded from the analyses. Correlations were calculated with the baseline values of each independent variable and anxiety and depression partialed out. Separate correlations were conducted for each dependent variable

p < 0.01,

p < 0.002 .

Table 4.

Partial correlations of anxiety with marijuana-related outcome measures

| Total N = 450 |

Delayed Treatment n = 148 |

MET alone n = 146 |

CBT-MET n = 156 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Time Period | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety | Anxiety |

| (4 months) | (9 months) | (4 months) | (9 months) | (4 months) | (9 months) | (4 months) | (9 months) | ||

| Marijuana problems | 4 months | 0.27** | 0.21* | 0.09 | N/A | 0.33** | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| 9 months | 0.27** | 0.29** | N/A | N/A | 0.17 | 0.29* | 0.35** | 0.28* | |

| per Times smoked day | 4 months | 0.27** | 0.25** | 0.09 | N/A | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.35** | 0.24 |

| 9 months | 0.26** | 0.19* | N/A | N/A | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.18 | |

| % days smoked | 4 months | 0.30** | 0.26** | 0.04 | N/A | 0.29* | 0.20 | 0.27* | 0.24 |

| 9 months | 0.25** | 0.28** | N/A | N/A | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.29* | |

| # weeks abstinent | 4 months | −0.30** | −0.30** | 0.10 | N/A | −0.27* | −0.25* | −0.28* | −0.28* |

| 9 months | −0.27** | 0.30** | N/A | N/A | −0.23 | −0.27* | −0.28* | −0.28* | |

Note. The delayed treatment condition was not assessed at the 9-month follow-up0. N/A=not assessed; MET = motivation enhancement therapy; CBT-MET = cognitive behavioral therapy plus motivation enhancement therapy. Correlations were calculated with the baseline values of each independent variable and anxiety and depression partialed out. Separate correlations were conducted for each dependent variable

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

3.5 Temporal associations between anxiety and marijuana outcomes

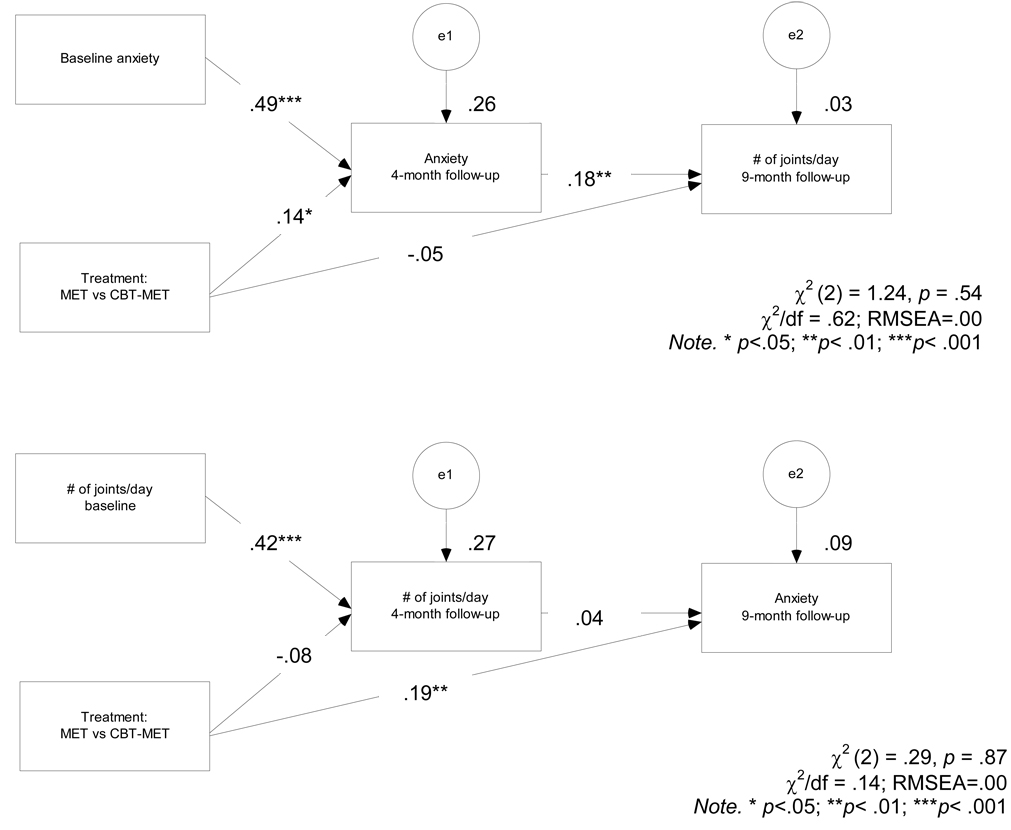

Path models were used to evaluate the temporal relations between anxiety and marijuana outcomes in the active treatments. Coefficients shown in Figure 1 are standardized. The first model tested the hypothesis that reduction in anxiety from pre-treatment to 4-months would be associated with fewer marijuana joints smoked per day at 9-months. This model fit to the data very well, χ2(2) = 1.24, p = 0.54, χ2/df = 0.62, RMSEA = 0.00. As expected, reductions in anxiety during treatment were significantly associated with fewer joints smoked per day at 9-months. Interestingly, this model suggests that treatment condition did not result in direct effect on joints per day at 9-month follow-up but rather the relation between treatment and 9-month smoking rate occurred indirectly through 4-month anxiety.

Figure 1.

Structural equation models showing (1) relationship between change in anxiety from baseline to 4-month follow-up and marijuana use outcome and (2) relationship between change in marijuana use from baseline to 4-month follow-up and anxiety outcome. MET=motivation enhancement therapy. CBT=cognitive-behavior therapy.

The second model tested the competing hypothesis that reductions in number of joints smoked per day from pre-treatment to 4-months would be associated with decreased anxiety at 9-months. This model also provided an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (2) = 0.29, p = 0.87, χ2/df = 0.14, RMSEA=0.00. However, the relation between joints per day at 4-months and 9-month anxiety was non-significant.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the impact of anxiety on the treatment of marijuana dependence. Using data from a large multisite trial of the efficacy of two psychosocial treatments for marijuana dependence (Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004), we found the following: First, higher pre-treatment anxiety was related to greater marijuana-related impairment (although not greater marijuana use frequency) and depression. Second, although pre-treatment anxiety was unrelated to treatment retention, higher levels of pre-treatment anxiety were related to more marijuana problems at both follow-up points (even after controlling for pre-treatment marijuana problems). This effect was evident for female but not male patients. Third, at both follow-ups, patients in the CBT-MET condition reported less anxiety than the MET condition. Fourth, change in anxiety was associated with marijuana outcomes such that reductions in anxiety during the course of the study were correlated with marijuana problems and less marijuana use at follow-up, particularly in the CBT-MET condition. Examination of the directionality of this relation suggested specificity such that reduction in anxiety from baseline to follow-up was associated with less marijuana use, but reduction in marijuana use did not predict subsequent anxiety.

4.1 Relations between baseline anxiety and pre-treatment functioning

Pre-treatment anxiety was positively related to greater marijuana-related impairment and depression. This finding is consistent with the notion that the combination of anxiety and marijuana dependence is particularly pernicious (Buckner et al., 2008b). Importantly, anxiety was associated with greater marijuana problems and days used other drugs even after controlling for depression, suggesting the relation between anxiety and marijuana-related problems is not better accounted for by this relevant negative affective state. This finding supports prior work indicating that anxiety appears related to marijuana use problems and disorders even after controlling for other types of negative affect (Buckner et al., 2006a; Buckner et al., 2006b; Zvolensky et al., 2006; Buckner et al., 2007; Buckner and Schmidt, 2008; Buckner et al., 2008b; Buckner et al., 2009; Buckner and Schmidt, in press).

4.2 Relations between treatment condition and post-treatment anxiety

As predicted, CBT-MET was associated with significantly less anxiety than MET alone by 9-months for the entire sample as well as for both men and women when analyses were conducted separately by sex. Although this finding differs from the prior report (Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group, 2004), the differential findings may be due to the utilization of an intent-to-treat sample in the present study (versus evaluation of the completer sample in the main report). Importantly, this finding was also obtained even after controlling for depression. Given that anxiety disorder treatment history is associated with reentry into marijuana treatment (Arendt et al., 2007), the finding that CBT-MET is associated with less anxiety at follow-up is noteworthy as patients with higher anxiety who receive CBT-MET may be less vulnerable to future relapse. Yet it is also of note that CBT-MET only resulted in an 18% reduction in anxiety. Future work in this area may benefit from exploration of treatments that integrate CBT techniques found efficacious for reducing anxiety with those aimed at managing marijuana use (see Stewart and Conrod, 2008).

Moreover, reduction in anxiety from baseline to both follow-up points was associated with less marijuana consumption at both follow-up points. On the other hand, increases in anxiety from baseline were associated with increases in marijuana use and marijuana-related problems at both 4- and 9-month follow-up. Given that the cessation of marijuana can increase anxiety (Wiesbeck et al., 1996), it follows that anxiety may naturally increase during the course of treatment. Although additional work is necessary to delineate the temporal relations between changes in anxiety and marijuana use during the course of treatment, the present data suggest that it may be important to address anxiety during marijuana treatment and that the neglect of anxiety may result in worse marijuana-related outcomes at follow-up.

4.3 Relations between change in anxiety on post-treatment marijuana outcomes

The question arises as to what may account for our finding that reductions in anxiety during the study were associated with better marijuana outcomes, particularly among patients in the CBT-MET condition. Consistent with tension-reduction and self-medication theories (e.g., Conger, 1956; Carrigan and Randall, 2003), one possible explanation is that CBT-MET taught patients skills to manage their anxiety, leading to decreased use of marijuana to manage anxiety. Conversely, it may be that CBT-MET led to less marijuana use which in turn resulted in less marijuana-induced anxiety. The present study tested these competing hypotheses and path analyses suggested that reduction in anxiety from baseline to 4-month follow-up was significantly associated with decreased marijuana use at 9-months, but that reductions in marijuana use from baseline to 4-months was not significantly related to 9-month anxiety. Taken together, these data are in line with tension-reduction theory and suggest that patients in marijuana treatment may benefit from the acquisition of skills to manage anxiety states. Future work is necessary to examine whether skill acquisition attributed to observed treatment gains.

4.4 Sex differences

Examination of the relations between anxiety, marijuana-related impairment, and treatment separately by sex suggest that, for the most part, the treatment of both men and women was impacted by anxiety. However, some noteworthy sex differences did emerge. Although anxiety was related to greater marijuana problems and psychiatric problems among both men and women, anxiety in men was linked to a wider variety of problems, including more legal and other drug problems. Given initial data indicating that the relation between marijuana and anxiety appears stronger for women compared to men (Buckner et al., 2006a; Buckner et al., 2009), it may be that marijuana dependent men with anxiety represent a specifically severe group of patients. However, among women (but not men), baseline anxiety was associated with greater number of post-treatment marijuana problems at both follow-ups. Interestingly, change in anxiety was more strongly related to marijuana outcomes among male patients, suggesting that anxious male patients may particularly benefit from treatments aimed at teaching patients skills to manage anxious responding. Clearly additional work is necessary to delineate the impact of anxiety on marijuana treatment for both male and female patients.

4.5 Limitations and future directions

The present study should be considered in light of limitations that suggest the need for additional work in this area. First, CBT-MET consisted of more sessions than MET alone. Although there is evidence that comparisons of brief MET to longer CBT have demonstrated comparable outcomes among substance abuse patients (e.g., Project MATCH Research Group, 1997), future work is necessary to delineate whether observed differences in anxiety during the course of treatment were due to skill acquisition by patients in the CBT-MET condition or whether the larger dose of treatment was responsible for observed differences. Second, the sample was comprised of treatment-seeking individuals. Thus the functional impairment experienced by individuals with levels of anxiety that impair their ability to seek treatment (e.g., individuals with high levels of social anxiety and/or agoraphobic avoidance) remains unknown. Third, there were few women in the sample and replication with larger samples of women is necessary. Fourth, exclusionary criteria included the presence of other substance use disorders. Given the high rates of alcohol dependence and other substance use disorders among anxious individuals (e.g., Kessler et al., 2005; Buckner et al., 2008b; Buckner et al., 2008c), this sample may not be representative of anxious individuals who use a variety of substances as a means to manage anxiety. Fifth, anxiety was measured using the state portion of the STAI which has been found to correlate highly with the BDI (Tanaka-Matsumi and Kameoka, 1986), raising questions as to whether this measure taps anxiety specifically or negative affect generally. Although we controlled for depression in analyses, future work using multiple measures of anxiety is warranted. Finally, the present study did not assess anxiety disorder diagnosis and future work is necessary to determine the impact of the co-occurrence of anxiety disorders on marijuana treatment.

4.6 Conclusions

The present study underscores the importance of the assessment and treatment of anxiety during treatment of marijuana dependence. Anxiety appears to be linked to greater marijuana-related impairment at treatment presentation and increases in anxiety during treatment appear associated with poorer marijuana-related outcomes. Given that CBT-MET resulted in significantly less anxiety than MET alone, CBT-MET may be the treatment of choice for marijuana dependence, particularly among patients who exhibit high levels of anxiety. Future work elucidating the mechanisms underlying the relations between anxiety and marijuana use in treatment could be utilized to further improve treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in partly by grants from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (UR4 TI11273, UR4 TI11310, UR4 TI11274, and UR4 TI11270). This research was also supported in part by National Institute on Drug Abuse (R37 DA 015969, K05 DA00457, P50 DA09241, R25 DA020515, and F31 DA021457).

We thank the other members of the Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group for their support of this project as well as Janice Vendetti and Charla Nich for their assistance with data management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Anxiety and other Axis I disorders were not assessed during the clinical interview.

A similar pattern emerged when depression not included as covariate

References

- Arendt M, Rosenberg R, Foldager L, Perto G, Munk-Jorgensen P. Psychopathology among cannabis-dependent treatment seekers and association with later substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LLB, Harp D, Jung WS. Reliability generalization of scores on the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2002;62:603–618. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:461–471. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD. Motivation enhancement therapy can increase utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy: The case of social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20641. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Marijuana use motives and social anxiety among marijuana using young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2238–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Ledley DR, Heimberg RG, Schmidt NB. Treating comorbid social anxiety and alcohol use disorders: Combining motivation enhancement therapy with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical Case Studies. 2008a;7:208–223. doi: 10.1177/1534650107306877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Leen-Feldner EW, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. The interactive effect of anxiety sensitivity and frequency of marijuana use in terms of anxious responding to bodily sensations among youth. Psychiatry Research. 2009;166:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Mallott MA, Schmidt NB, Taylor J. Peer influence and gender differences in problematic cannabis use among individuals with social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006a;20:1087–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. Marijuana effect expectancies: Relations to social anxiety and marijuana use problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1477–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. A randomized pilot study of motivation enhancement therapy to increase utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety disorder and marijuana use problems: The mediating role of marijuana effect expectancies. Depression and Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.20567. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Bobadilla L, Taylor J. Social anxiety and problematic cannabis use: Evaluating the moderating role of stress reactivity and perceived coping. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006b;44:1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small J, Schlauch RC, Lewinsohn PM. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008b;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Timpano KR, Zvolensky MJ, Sachs-Ericsson N, Schmidt NB. Implications of comorbid alcohol dependence among individuals with social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2008c;25:1028–1037. doi: 10.1002/da.20442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Radonovich KJ, Novy PL. Adding voucher-based incentives to coping skills and motivational enhancement improves outcomes during treatment for marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1051–1061. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Moore BA, Rocha HL, Higgins ST. Clinical trial of abstinence-based vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:307–316. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.4.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan MH, Randall CL. Self-medication in social phobia: A review of the alcohol literature. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:269–284. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Easton CJ, Nich C, Hunkele KA, Neavins TM, Sinha R, Ford HL, Vitolo SA, Doebrick CA, Rounsaville BJ. The use of contingency management and motivational/skills-building therapy to treat young adults with marijuana dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:955–966. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JS, Furr JM, Beidas RS, Weiner CL, Kendall PC. Children and terrorism-related news: Training parents in coping and media literacy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:568–578. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger JJ. Alcoholism: Theory, problem and challenge. II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1956;17:296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Swift W, Rees V. Clinical profile of participants in a brief intervention program for cannabis use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;20:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Biometrics Research Department. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway AD. Cannabis effects and dependency concerns in long-term frequent users: A missing piece of the public health puzzle. Addiction Research and Theory. 2003;11:441–458. [Google Scholar]

- Kadden RM, Carroll KM, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P, Abrams D, Litt MD, Hester R. Washington, DC: U. S. Government Printing Office; 1992. Cognitive–behavioral coping skills therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. (DHHS Publication No. ADM 92-1895) [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltby N, Tolin DF. A brief motivational intervention for treatment-refusing OCD patients. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2005;34:176–184. doi: 10.1080/16506070510043741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: Findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:455–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, H P, M A. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational Enhancement Therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ogborne AC, Smart RG, Weber T, Birchmore-Timney C. Who is using cannabis as a medicine and why: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:435–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH Posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly D, Didcott P, Swift W, Hall W. Long-term cannabis use: Characteristics of users in an Australian rural area. Addiction. 1998;93:837–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9368375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Time line follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorusch RL, Lushene RE, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg KL, Roffman RA, Carroll KM, Kabela E, Kadden R, Miller M, Duresky D. Tailoring cannabis dependence treatment for a diverse population. Addiction. 2002;97:135–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Babor TF, Kadden R, Miller M. The Marijuana Treatment Project: Rationale, design and participant characteristics. Addiction. 2002;97:109–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Simpson EE. Treating adult marijuana dependence: A test of the relapse prevention model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:92–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Conrod PJ. Anxiety disorder and substance use disorder co-morbidity: Common themes and future directions. In: Stewart SH, Conrod PJ, editors. Anxiety and substance use disorders: The vicious cycle of comorbidity. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. In: Mattson ME, Donovan DM, editors. Alcoholism Treatment Matching Research: Methodological and Clinical Approaches. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka-Matsumi J, Kameoka VA. Reliabilities and concurrent validities of popular self-report measures of depression, anxiety, and social desirability. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:328–333. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevos AK, Thomas SE, Randall CL. Baseline differences in social support among treatment-seeking alcoholics with and without social phobia. Substance Abuse. 1999;20:107–121. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SE, Thevos AK, Randall CL. Alcoholics with and without social phobia: A comparison of substance use and psychiatric variables. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:472–479. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen A, Foa EB. The effect of imaginal exposure length on outcome of treatment for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:427–438. doi: 10.1002/jts.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Dozois DJA. Preparing clients for cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing for anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesbeck GA, Schuckit MA, Kalmijn JA, Tipp JE, Bucholz KK, Smith TL. An evaluation of the history of a marijuana withdrawal syndrome in a large population. Addiction. 1996;91:1469–1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Sachs-Ericsson N, Schmidt NB, Buckner JD, Bonn-Miller MO. Lifetime associations between cannabis, use, abuse, and dependence and panic attacks in a representative sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:477–786. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Johnson K, Hogan J, Bernstein A, Bonn-Miller MO. Relations between anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and fear reactivity to bodily sensations to coping and conformity marijuana use motives among young adult marijuana users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:31–42. doi: 10.1037/a0014961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]