Abstract

A family of triazine dendrimers, differing in their core flexibility, generation number, and surface functionality, was prepared and evaluated for its ability to accomplish RNAi. The dendriplexes were analyzed with respect to their physicochemical and biological properties, including condensation of siRNA, complex size, surface charge, cellular uptake and subcellular distribution, their potential for reporter gene knockdown in HeLa/Luc cells, and ultimately their stability, biodistribution, pharmacokinetics and intracellular uptake in mice after intravenous (iv.) administration. The structure of the backbone was found to significantly influence siRNA transfection efficiency, with rigid, second generation dendrimers displaying higher gene knockdown than the flexible analogues while maintaining less off-target effects than Lipofectamine. Additionally, among the rigid, second generation dendrimers, those with either arginine-like exteriors or peripheries containing hydrophobic functionalities mediated the most effective gene knockdown, thus showing that dendrimer surface groups also affect transfection efficiency. Moreover, these two most effective dendriplexes were stable in circulation upon intravenous administration and showed passive targeting to the lung. Both dendriplex formulations were taken up into the alveolar epithelium, making them promising candidates for RNAi in the lung. The ability to correlate the effects of triazine dendrimer core scaffolds, generation number, and surface functionality with siRNA transfection efficiency yields valuable information for further modifying this non-viral delivery system and stresses the importance of only loosely correlating effective gene delivery vectors with siRNA transfection agents.

Keywords: Triazine dendrimers, RNA interference, structure function relationship, physico-chemical characterization, in vivo, biodistribution, SPECT imaging, lung targeting

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) has shown promise in treating various genetic and acquired diseases such as cancer, HIV, and cardiovascular disease, and has been described in many reviews.1-6 However, delivering siRNA for gene silencing faces a variety of obstacles that may differ from those faced when delivering DNA. While both DNA and siRNA are double stranded nucleic acids, there are several fundamental structural differences between siRNA and DNA that impact the effectiveness of a carrier in promoting transfection. First, there is a clear difference in molecular topology between plasmid DNA and siRNA with respect to persistence length, which relates to the stiffness of the material. The length scale over which DNA behaves as a rigid rod is 50 nm,7 while the length for double stranded RNA is 70 nm,8 indicating that RNA is less flexible. In fact, it is not until RNA is approximately 260 bp in length before the chain becomes flexible.9 Consequently, 21-27 bp siRNA does not “compact” when complexed with a carrier as does plasmid DNA, and incomplete encapsulation or the formation of undesirably large complexes often results. Studies have shown that for siRNA-poly(ethylene imine) complexes, particle size directly correlates with transfection efficiency, and complexes > 150 nm in diameter show no gene knockdown in vitro.10 Due to the dissimilar flexibility and because the site of action for siRNA is the cytosol and not the nucleus, as in case of DNA,11 carriers that are shown to efficiently deliver plasmids are not necessarily optimal for siRNA transfection, and vice versa.12-14 Despite facing less cellular trafficking requirements, siRNA is more prone to hydrolysis when exposed to serum nucleases as compared to DNA. While modifications at the 2′-position on the sugar-phosphate backbone of siRNA can improve serum stability,15 complete encapsulation by a carrier agent still provides the best protection from degradation.

Various dendrimers have been investigated as carriers for siRNA transfection. While carbosilane dendrimers,16-18 PPI dendrimers,19 and dendritic PLL20 have all shown potential for delivery of siRNA, PAMAM dendrimers and their derivatives have been the most widely studied dendritic structures with respect to RNAi.21, 22 Recently, various groups have investigated the effect of PAMAM peripheral group manipulations on siRNA transfection efficiency, including Tat-conjugation of PAMAM G5 dendrimersto improve cellular uptake,23 acetylation of PAMAM dendrimers to reduce the number of primary amines thus improving biocompatibility and increasing intracellular release of siRNA,24 quaternization of the internal amines to increase cationic charge at physiological pH,25 and the formation of hydroxyl-terminated PAMAM G4 dendrimers with quaternized internal amines.26 In addition to peripheral group manipulations, the core and generation number of PAMAM dendrimers has been modified to affect siRNA transfection efficiency, as described by Peng, et al. for PAMAM dendrimers (G4-G7) with a triethanolamine core to increase flexibility.27 Based on the results obtained in the past by other groups using various peripherally- and core-modified PAMAM dendrimers, it is clear that both surface group and dendrimer scaffold manipulations significantly impact dendrimer-mediated siRNA transfection efficiency. For PAMAM dendrimers, it appears that incorporating neutral groups into the periphery can reduce cytotoxicity, although this may result in reduced cellular uptake of the dendrimer-siRNA complex as well. Alternatively, increasing flexibility and/or generation number appears to improve gene knockdown effects. In this study, we aim to determine if triazine dendrimers, which have been used successfully for DNA transfection,28, 29 are capable of efficiently delivering siRNA to its site of action. In our previous studies, it was shown that DNA transfection efficiency was affected moderately by the surface groups on the periphery of the dendrimers29 and drastically by the dendrimer core structure.28 In continuation we aim to elucidate structure-activity relationships regarding the impact of peripheral and core functionality of triazine dendrimers on complex formation with siRNA by assessment of in vitro and in vivo stability, cellular uptake and subcellular distribution, in vitro transfection efficiency, and in vivo biodistribution.

Experimental Section

Materials

Poly(ethylene imine) (Polymin™, 25 kDa) was a gift from BASF (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Lipofectamine™2000 (LF) was bought from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany), SuperFect™ (SF) from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany), generation 2 PAMAM (ethylenediamine core, amino surface), Beetle Luciferin, and heparin sodium salt from Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien GmbH (Seelze, Germany). 2′-O-Methylated 25/27mer DsiRNA targeting firefly luciferase (FLuc, sense: 5′-pGGUUCCUGGAACAAUUGCUUUUAdCdA, antisense: 3′-mGmAmCCmAAmGGmACmCUmUGmUUmAAmCGAAAAUGU), negative control sequence (NegCon, sense: 5′-pCGUUAAUCGCGUAUAAUACGCGUdAdT, antisense: 3′-mCmAmGCmAAmUUmAGmCGmCAmUAmUUmAUGCGCAUAp), AlexaFluor488-, TYE546- and 5′-sense strand C6-amine modified DsiRNA were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Leuven, Belgium). Balb/c mice were bought from Harlan Laboratories (Horst, The Netherlands). The chelator 2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-DTPA) was purchased from Macrocyclics (Dallas, TX, USA), SYBR® Gold from Invitrogen (Karlsruhe, Germany), and all chemicals used for synthesis were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Synthesis

The triazine dendrimers used in this study were synthesized following a divergent approach as previously described.28, 29 The final products and all intermediate structures were characterized by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry.

Dendriplex formation

Dendriplexes were formed by adding 25 μl of a calculated concentration of dendrimer to an equal volume of 2 μM siRNA followed by vigorous pipetting before letting the dendriplexes mature for 20 min. The final concentration of siRNA was 1 μM. Both siRNA and dendrimers were diluted with anisotonic solution of 5% glucose. The appropriate amount of dendrimer was calculated as previously described28 by considering the desired N/P ratio and the “protonable unit” of each dendrimer, which represents the mass of dendrimer per protonable nitrogen atom. Polyplexes with PEI 25 kDa and dendriplexes with generation 2 PAMAM were formed as described above, whereas dendriplexes with SF were prepared at a 2:1 ratio and lipoplexes with LF with 1 μl per 20 pmol, as recommended by the manufacturers.

SYBR Gold® Assay

The ability of various dendrimers to condense siRNA into small dendriplexes was studied as previously reported.30 Briefly, 1 μg of luciferase-targeting siRNA was complexed with dendrimers at different N/P ratios in opaque FluoroNunc™ 96 well plates (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Langenselbold, Germany) and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Into each well, 50 μl of a 1x SYBR® Gold solution was added and incubated for 10 minutes in the dark. Intercalation-caused fluorescence was quantified using a SAFIRE II fluorescence plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 495 nm excitation and 537 nm emission wavelengths. For comparison, siRNA was complexed with PEI 25 k and generation 2 PAMAM as well. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are given as mean relative fluorescence intensity values +/− the standard deviation (SD), where intercalation of free siRNA represents 100 % fluorescence and non-intercalating SYBR® Gold in buffer represents 0 % remaining fluorescence.

Heparin Competition Assay

The stability of the dendriplexes to competing polyanions, which are present under in vivo conditions, was studied with the model molecule heparin similar to what was previously reported.30 Briefly, dendriplexes were formed at N/P=5 and incubated with 50 μl of a 1x SYBR® Gold solution for 10 minutes in the dark before increasing amounts of heparin were added and incubated with the polyplexesfor another 20 minutes. Fluorescence was quantified as described above. In this assay, siRNA was also complexed with PEI 25k and generation 2 PAMAM for comparison. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are given as mean relative fluorescence intensity values +/− SD, where free siRNA represents 100 % fluorescence and SYBR® Gold in buffer represents 0 % fluorescence.

Dynamic Light Scattering and Zeta Potential Analysis

Dendriplexes of various triazine dendrimers and siRNA were characterized concerning their hydrodynamic diameters and zeta potentials. PAMAM generation 2 and PEI 25k were used to form control dendriplexes and polyplexes, respectively. For dynamic light scattering, dendriplexes and PEI polyplexes were formed in 5 % glucose at N/P ratio 5 with 50 pmol siRNA in a final volume of 50 μl and measured in a disposable low volume UVette (Eppendorf, Wesseling-Berzdorf, Germany) using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern, Herrenberg, Germany) equipped with a 4 mW He–Ne laser at a wavelength of 633 nm at 25 °C. Position and attenuator were optimized by the device. Zeta potentials were determined with the same device by laser Doppler anemometry (LDA) after diluting the samples with 750 μl 5 % glucose to a final volume of 800 μl and transferring the suspensions into a green zeta cuvette (Malvern, Herrenberg, Germany).. Scattered light was detected at a 173° backward scattering angle. Data were analyzed using a High Resolution Multimodal algorithm. Measurements were conducted in triplicate. Results are given as mean values +/− SD.

Cell Culture

HeLa cells that stably express luciferase (HeLa/Luc) were obtained by transfection of a linearized plasmid (pTRE2hygLuc, Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) and selection of single clones under pressure of 100μg/ml hygromycin B (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) as previously reported.31 HeLa/Luc cells were maintained at 100μg/ml hygromycin B in DMEM high glucose (PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany), supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Cytogen, Sinn, Germany),in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2 at 37°C.

Transfection efficiency

In a cell culture model using HeLa/Luc cells, which stably express the luciferase gene, the siRNA transfection efficiency of the different dendrimers was screened. Cells were seeded at a density of 15,000 cells per well on 48-well-plates in the absence of hygromycin B 24 hours prior to transfection. The cells were treated with dendriplexes of 50 pmol siRNA (siFLuc) or non-specific control (siNegCon) and the dendrimers at N/P 5 in a total volume of 500 μl. As positive controls, siRNA was complexed with the commercially available transfection reagents Lipofectamine™2000 and SuperFect™. The medium was changed 4 hours post transfection, and cells were incubated for another 44 hours. Following incubation, the cells were washed with PBS buffer, lysed with CCLR (Promega) and assayed for luciferase expression with a 10 mM luciferin solution on a BMG luminometer plate reader. Transfections were performed in replicates of four, and the results are given as mean values +/− SD.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

Uptake and subcellular distribution of dendriplexes was investigated by plating HeLa/Luc cells at a density of 15,000 cells per chamber on 16-chamber slides. The cells were transfected 24 hours later with dendriplexes prepared using various triazine dendrimers at N/P ratio 5 and 20 pmol TYE-546-labeled siRNA per chamber in a total volume of 200 μl. As positive controls, the commercially available transfection reagents Lipofectamine™2000 and SuperFect™ were used. Cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 before they were washed and fixed on the slides with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) before the samples were embedded with FluorSave (Calbiochem, Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany). A Zeiss Axiovert 100 M microscope coupled to a Zeiss LSM 510 scanning device (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for confocal microscopy. DAPI-stained chromosomal DNA was excited with an enterprise laser with an excitation wavelength of 364 nm, TYE-546-labeled siRNA with a helium-neon laser with an excitation wavelength of 543 nm. Fluorescence emission of DAPI was detected in channel 1 with a 385 nm long pass filter and emission of TYE-546 in channel 2 with a 560 nm long pass filter. DAPI- and TYE-546- fluorescence and overlay of transmission light was recorded.

Flow Cytometry

The intracellular uptake of dendriplexes was quantified by flow cytometry. HeLa/Luc cells were seeded in 48 well plates at a density of 30,000 cells per well and transfected 24 hours later with dendriplexes consisting of 50 pmol Alexa488-labeled siRNA at N/P 5. Cells were incubated with the dendriplexes for 4 h at 37 °C before they were washed with PBS. For comparison, siRNA was complexed with the commercially available transfection reagents Lipofectamine™2000 and SuperFect™ and with PEI25k. Surface-bound fluorescence was quenched by incubating the cells for 5 min with 0.4% trypan blue32 before the cells were trypsinized and fixed with a 1:1 mixture of FACSFlow (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Fixed cells were measured using a FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with excitation at 488 nm and the emission filter set to a 530/30 bandpass. Cells were gated to evaluate 10,000 viable cells in each experiment, and results of the geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are given as the mean value of 3 independent measurements. Data acquisition and analysis was performed using FACSDiva™ software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Radiolabeling and Purification

To investigate both the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of vector and payload, and to determine if dendriplexes are stable in vivo after i.v. injection, we radiolabeled the dendrimers and siRNA and administered dendriplexes formed with either radiolabeled siRNA or radiolabeled dendrimer. siRNA was labeled and purified as previously described.31, 33 Briefly, amine-modified siRNA was mixed with p-Bn-SCN-DTPA at pH 8.5 and reacted for 45 min before it was precipitated in absolute ethanol overnight. Dendrimers were labeled similarly to polymers31 by adjusting a dendrimer solution of 10 mg/ml with 0.2 M NaHCO3 to pH 8.5 and adding p-Bn-SCN-DTPA. The amount of p-Bn-SCN-DTPA was calculated to equal 10% of the amines present in the dendrimer to maintain sufficient amounts of primary amines in the dendrimer for complexation of siRNA. Unreacted DTPA was removed after 45 minutes of incubation by ultrafiltration using Microsep™ 1k Centrifugal Devices (Pall Life Sciences, Dreieich, Germany). DTPA-coupled dendrimers and siRNA, respectively, were then incubated for 30 min with 111InCl3 (Covidien Deutschland GmbH, Neustadt a.d. Donau, Germany) in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.4 for radiolabeling and purified from free 111InCl3 by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on PD-10 Sephadex G25 (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany) and additional RNeasy spin column purification in case of siRNA, as described earlier.30, 31, 33

In vivo Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution

All animal experiments were carried out according to the German law of protection of animal life and were approved by an external review committee for laboratory animal care. Four to six week old BALB/c mice were anesthetized with xylazine and ketamine and injected with dendriplexes containing 35 μg of siRNA and the corresponding amount of dendrimer at N/P 6. In two control groups, mice were injected with PEI25k/siRNA polyplexes which were prepared and labeled as previously described.31 Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution were determined as previously reported.31 Briefly, blood samples were withdrawn retro-orbitally and pharmacokinetic profiles were calculated using Kinetica 5.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific/ Cypress Software Inc., Langley, WA, USA). Three-dimensional SPECT and planar gamma camera images were recorded 2 h after injection using a Siemens e.cam gamma camera (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a custom built multiplexing multipinhole collimator. Kinetics of biodistribution were followed by planar perfusion live imaging as previously reported.33 In the first phase of the perfusion study, one picture was taken every second for 400 seconds. In the second phase, 14 minutes long, one picture was taken every minute. Planar static and dynamic images were analyzed for radioactivity in regions of interest (ROIs) and SPECT images were reconstructed using Syngo software (Syngo, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). After 2 h, animals were sacrificed and the biodistribution in dissected organs was measured using a Gamma Counter Packard 5005 (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT).

Cellular Tissue Distribution of in vivo Transfected Cells

For microscopic evaluation of the tissue distribution of the administered siRNA, mice were injected with dendriplexes of 35 μg TYE-546-labeled siRNA and the corresponding amount of dendrimer for N/P 6. Animals were sacrificed 2 and 24 h after injection, respectively, and the major organs were dissected and stored in 4% paraformaldehyde in the dark, before they were embedded in paraffin. The deparaffinized slices (3 μm) were counterstained with 1 μg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) solution in PBS for 30 minutes under light exclusion, and embedded with FluorSave (Calbiochem, Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany) to protect the fluorophores. DAPI- and TYE-546- fluorescence and overlay of transmission light of the tissue sections was recorded with the confocal microscope as described above.

Statistics

All analytical assays were conducted in replicates of three or four, as indicated, and all in vivo experiments included 5 animals per group. Results are given as mean values +/− standard deviation (SD). Two way ANOVA and statistical evaluations were performed using Graph Pad Prism 4.03 (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, USA). The AUC was calculated using Kinetica 5.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific/ Cypress Software Inc., Langley, WA, USA).

Results and Discussion

Nomenclature of the synthesized dendrimers

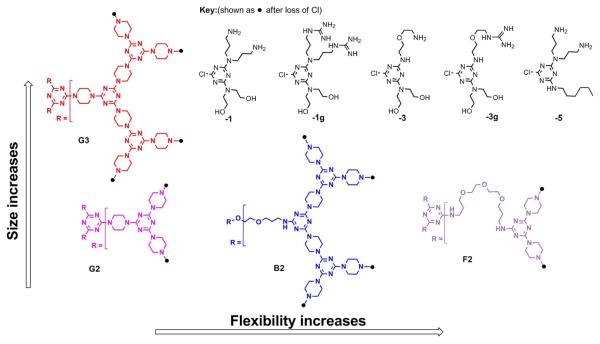

The target dendrimers described in this manuscript are designated to reflect common and disparate features with respect to both the core structure and surface group functionalities. The cores differ in flexibility, increasing from G (rigid) to B (bowtie) to F (flexible) structures. In addition, the rigid cores include both second (prefix 2) and third (prefix 3) generations. The peripheral groups include triazines with varying numbers of hydroxyl groups and amines (suffixes 1 and 3), hydroxyl groups and guanidinylated amines (suffix 1g), and short alkyl chains and amines (suffix 5). The nomenclature has been adopted to reflect the degree of flexibility, the generation number, and the peripheral groups in that order and is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of triazine dendrimer cores and peripheral groups. The cores are labeled based on their degree of flexibility (rigid = G, bow-tie = B, and flexible = F) and generation number (2 or 3). The monochlorotriazines from which the peripheral groups were obtained are labeled based on the substitutions (hydroxyl groups and amines = 1 or 3, hydroxyl groups and guanidinylated amines = 1g or 3g, and alkyl chain and amines = 5).

Synthesis and design criteria

Multistep organic synthesis enables the formation of triazine dendrimers with well-defined structures with specific diamine groups linking the triazine subunits of each generation. The ability to easily manipulate both the core and the periphery of the dendrimers enables the investigation of specific structure-activity relationships, including the influence of size, backbone structure, and surface functionality on both gene knockdown potential and cytotoxicity. For this investigation, a panel of triazine dendrimers was synthesized as previously described to include rigid core structures at different generations (G2 and G3) to probe the effect of increasing amine number on siRNA transfection efficiency. In addition, the second generation rigid structures were synthesized to include an assortment of peripheral groups to investigate the effects of the amount of amines present in the periphery and the effects of incorporating either arginine-like functionality or more hydrophobic functional groups on biophysicochemical properties of complexes with siRNA. While the role of vector flexibility in siRNA transfection is limited to only a few investigations, enhanced pDNA transfection efficiency by less dense, activated PAMAM (i.e. Superfect and Polyfect)was demonstrated experimentally.34 In addition, previous investigations of gene transfer using triazine dendrimers has shown that flexibility is a key factor for promoting pDNA transfection.28 In this study, the effect of the triazine dendrimer flexibility on RNAi is investigated using different core structures (G2, F2, B2). The syntheses of most of these structures have been previously reported.28, 29 The synthetic yields and NMR spectroscopic data for previously unreported structures are provided in the Supporting Information. The composition of the panel is summarized in Figure 1. For the physicochemical and biological assays, branched poly(ethylene imine) of 25 kDa (PEI 25kDa) and/or LF, generation 2 PAMAM (ethylenediamine core, amino surface) or SF (generation 4 activatedPAMAM) were used as controls.

Condensation efficiency

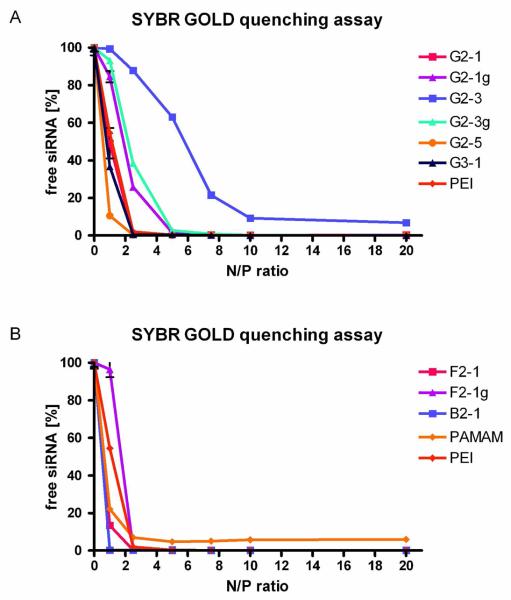

The condensation of siRNA by various dendrimers was investigated by SYBR Gold assays,30 which give an idea of how much siRNA is still present as free or accessible siRNA that is able to interact with SYBR Gold. The amount of siRNA that is protected from intercalation with SYBR Gold is most probably also protected from nucleases. Since most of the dendrimers in this study were generation 2 dendrimers, as control reagents, PEI 25k and generation 2 PAMAM were used. As shown in Figure 2, condensation properties of the dendrimers were most importantly controlled by the end group modification rather than by core flexibility (compare Figure 2). While dendrimer G2-1 showed siRNA condensation comparable to condensation by PEI 25k, dendrimer G2-3, on the other hand, condensed siRNA to a much lower extent, due to the lower number of primary amines in its periphery and resulting lower charge density. 28 G2-5, the alkylated dendrimer, condensed siRNA to 80 % at N/P 1 and showed the best condensation properties among the G2 dendrimers. This trend is in line with our observations of DNA condensation.29 Guanidinylation of dendrimers leads to very similar condensation profiles, independent of the number of guanidinium end groups and core flexibility (compare Figure 2B: F2-1g), and slightly lower condensation as compared to PEI 25k at N/P ratios below 5. The increase of primary amines in the periphery, accomplished in dendrimer G3-1, only slightly improved condensation of siRNA. This contrasts with previous results in which DNA condensation was significantly improved by increasing the generation.28 DNA seems to form a wider range of three-dimensional structures and can therefore interact better with all amines present, whereas the rigidity of siRNA8 prevents better interaction with G3-1. The condensation properties of the more flexible dendrimers B2-1 and F2-1 were similar to each other, while B2-1 already achieved complete condensation at N/P 1. As reported for DNA condensation, the influence of the core structure on condensation properties is rather low.28

Figure 2.

Complexation behavior of dendrimers as measured by SYBR Gold intercalation of residual free siRNA at increasing N/P ratios.

Accordingly, F2-1g exhibited a condensation profile comparable to G2-1g and G2-3g. We therefore assume that guanidinium end groups influence the condensation of siRNA irrespective of other structural properties, such as core flexibility. The PAMAM dendrimer, however, was the only reagent where a plateau of 5% free siRNA remained even at N/P 20, which indicates that triazine dendrimers can more efficiently condense and protect siRNA than PAMAM dendrimers of the same generation. The same inability to completely condense DNA had been observed for PAMAM dendrimers of second and third generation.28

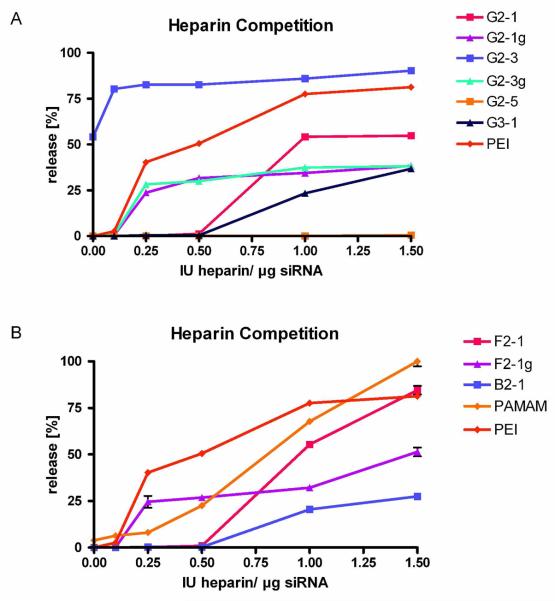

Stability against competing polyanions

The stability of electrostatically formed complexes is subject to the presence of competing ions.35 Due to the release of counter-ions upon complex formation, the process of polycation-nucleic acid interaction is entropy driven36 and can be significantly influenced by the presence of other polyions. Moreover, the stability of these complexes is often strongly impaired by the presence of serum,31 and the uptake of intact complexes into cells can additionally be impeded by interaction of the polycation with negatively charged proteoglycans on the cell surface.37 Heparin therefore acts as a model polyanion competing with nucleic acids for electrostatic interaction with polycations. The stability of the complexes to heparin was measured by quantification of siRNA released from the complexes after intercalation with SYBR Gold. Strong differences in the stability profiles of the various dendriplexes were again observed to be related to end group modification (Figure 3A). Dendriplexes of G2-1 did not release siRNA up to 0.5 IU heparin per μg siRNA and were thus more stable than PEI complexes. Dendrimer G2-3 formed unstable complexes with more than 50% free siRNA before addition of heparin as described above. The complexed portion of the siRNA was easily released from the loose complexes upon treatment with concentrations of heparin as low as 0.1 IU per μg siRNA. Dendriplexes made with G2-5 were completely stable over the whole concentration range of heparin investigated (0.1-1.5 IU heparin per μg RNA), which can be explained by rather hydrophobic interactions of the alkylated dendrimer with the amphiphilic 2′-O-methylated siRNA, which, of course, are untainted withcompeting polyanions. The higher stability of all dendriplexes (except for G2-3) compared to PEI polyplexes can be explained by additional van der Waals forces between the triazines/piperazines and the amphiphilic siRNA. These interactions, however, are not strong enough to replace electrostatic interactions between phosphates and protonated primary amines, as shown by the lack of stability of G2-3 dendriplexes.

Figure 3.

In vitro stability of dendriplexes as measured by SYBR Gold intercalation of displaced siRNA at increasing concentrations of heparin.

Similar to the previously discussed condensation efficiency with siRNA, guanidinium-modified dendrimers all showed comparable stability profiles, independent of the amount of guanidinium groups or core flexibility (compare Figure 3B: F2-1g). Guanidinylation has previously been reported to show increased interaction with DNA as compared to amine structures.38 Higher stability of G2-1g, G2-3g, and F2-1g dendriplexes compared to G2-1, G2-3, and F2-1 was observed in our study especially at heparin concentrations of 1 IU heparin per μg siRNA and above. While PEI complexes released 81% of their siRNA load at 1.5 1 IU heparin per μg RNA, G2-1 dendriplexes released only 55%, while the guanidinylated counterpart G2-1g performed even better with only 38% released siRNA. As shown in Figure 3B and discussed above with respect to complexation behavior, the increase of generation did not yield a higher stability of G3-1 dendriplexes. The stability profile of G3-1 is comparable to that of G2-1 at low heparin concentrations. Release of siRNA starts at heparin 0.5 IU heparin per μg RNA, while G2-1 releases 55% and G3-1 only 37% of the siRNA at. B2-1 dendriplexes featured a similar profile, but show slightly higher stability with a maximum of 27 % of released siRNA at 1.5 1 IU heparin per μg RNA. Although F2-1 more efficiently condensed siRNA than G3-1 and PEI, the stability of its dendriplexes was lower compared to G3-1 at heparin concentrations of 0.5 IU per μg siRNA and above. As described above, the stability of guanidinylated dendriplexes was determined by their end group modification. While the release profiles of G2-1g and G2-3g had already reached a plateau of 30% released payload at 0.25 IU heparin per well and 38% released siRNA at 1.5 IU heparin, F2-1g complexes were more stable at 0.25 IU heparin (24% released siRNA), but released up to 51% of their payload at the highest heparin concentration of 1.5 IU per well.

PAMAM dendriplexes, on the other hand, were the only complexes that released 100% of their payload at 1.5 IU heparin. The stability of these complexes showed a nearly sigmoidal course with comparably good stability at low heparin concentrations and low stability above 0.5 IU heparin per μg siRNA.

Since the stability profiles of all triazine dendriplexes (except for G2-3) were better compared to PEI and PAMAM, we hypothesize that hydrophobic elements in the dendrimers, including the triazine and piperazine units, are favorable, given that the electrostatic interactions between nucleic acids and polycations are strong enough for efficient condensation at the low generation number.

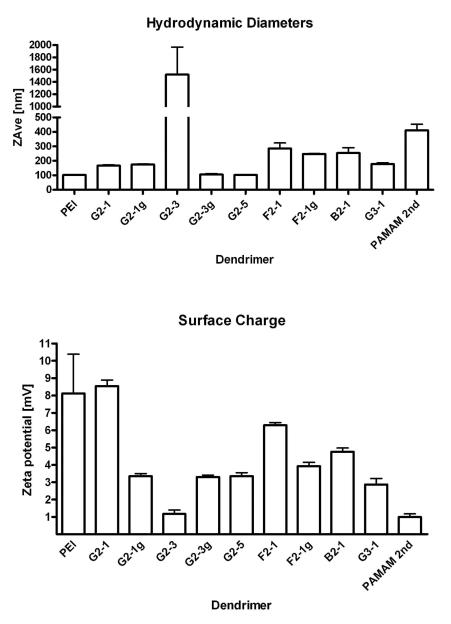

Size and zeta potential

Hydrodynamic diameters and zeta potentials were measured to better characterize the dendriplexes. Except for G2-3, all dendrimers formed complexes in the nanometer scale. The smallest complexes of 105 and 103 nm, respectively, were formed with G2-3g and G2-5, and are comparable in size to PEI complexes of 103 nm, as shown in Figure 4 A. G2-1 has twice the amount of primary amines in its periphery (protonable unit: 245 g/ mol N) as compared to G2-3 (protonable unit: 507 g/ mol N) and formed complexes of 167 nm with an essentially lower amount of dendrimer mass. Guanidinylation did not essentially change the sizes of dendriplexes in the case of G2-1g and F2-1g, in contrast to G2-3g, which formed especially small complexes of 103 nm. As seen in the condensation profiles, guanidinylation had notable effect only if a low number of primary amines was present in the periphery of the dendrimer. The flexible dendrimer F2-1 formed complexes of 286 nm, which were larger than the complexes made using the rigid dendrimers. These observations are in line with our previously reported simulations of interaction of rigid and flexible triazine dendrimers with nucleic acids. Since the flexible structures collapse in solution, there are only a few contacts possible between the peripheral amines and the siRNA.39 The interaction of peripheral amines of the rigid dendrimers with phosphates of siRNA, on the other hand, has been calculated to be more pronounced and more numerous due to the reorganization that the rigid dendrimers undergo upon binding.39 B2-1, the dendrimer that was designed to represent intermediate flexibility, formed complexes of 255 nm in size although the condensation efficiency of this dendrimer was especially high. Since the delineation of the condensation characteristics of a dendrimer, however, is not capable of predicting the molecular or stoichiometric composition of the dendriplexes, the measurement of hydrodynamic diameters is especially important in characterizing the complexes. In the case of B2-1, whose complexation with nucleic acids has not yet been simulated, it can be hypothesized that a collapsed structure is present, which results in less interaction sites available for nucleic acid binding as was observed for the flexible dendrimers F2-1 and F2-1g. Another explanation might be formation of inter-dendriplex aggregates, which have been observed in AFM micrographs of DNA complexes with B2-1.28 Dendriplexes of G3-1 exhibited larger complex sizes compared to generation 2 dendriplexes. Since it was shown that the piperazine linker in the rigid dendrimers positions the peripheral groups at a significant distance from each other and the core,39 it must be noted that this distance is increased for generation 3. For interaction with siRNA, this increase in distance between the charged groups seems to be less favorable, resulting in larger complexes, where possibly a larger number of molecules is involved.

Figure 4.

Hydrodynamic diameters of dendrimer/siRNA complexes as determined by dynamic light scattering. The dendriplexes were formed at N/P ratio 5 at a concentration of 50 pmol siRNA in 50 μl of 5 % glucose.

The zeta potentials of the various complexes, shown in Figure 4B, provide another indication that supports this hypothesis. G2-1 dendriplexes exhibited a zeta potential of 8.5 mV, which is comparable to PEI complexes of 8.1 mV, signaling the presence of protonated amines on the surface of these complexes. Due to their low number of primary amines, G2-3 dendriplexes exhibited an almost neutral zeta potential of only 1.2 mV. In previous studies, this dendrimer exhibited a negative zeta potential upon DNA complexation,.29 which suggested this complex to be an unsuitable carrier. In the case of G2-5, the amount of measurable positive charges on the surface of the dendriplexes is decreased compared to G2-1, which has the same amount of primary amines in the periphery. We therefore hypothesize that, due to the alkyl chains in the dendrimer, the dendriplex conformation may be different from G2-1. As shown in the heparin displacement assay, there seem to be additional van der Waals interactions between G2-5 and 2′-O-Me siRNA. These interactions may lead to a higher number of contacts between the amines of the dendrimer and phosphates in the siRNA, causing stronger neutralization of the positive charges. F2-1, on the other hand, which has been shown to interact less with siRNA than G2-5,39 did exhibit a higher zeta potential than G2-5.

This can be understood as a function of protonated amines which are not neutralized by interaction with siRNA. In comparison to G2-1, however, the zeta potential of F2-1 is decreased as a result of its collapsed structure39 or the fact that a larger number of siRNA molecules interact with the dendrimer, leading to stronger charge neutralization. This had already been assumed for F2-1, B2-1 and G3-1 regarding their hydrodynamic diameters and may be admissible as indicated by the further decreased zeta potentials of 4.8 and 3.9 mV for B2-1 and G3-1, respectively. PAMAM formed the largest dendriplex, excluding G2-3, with a hydrodynamic diameter of 411 nm and a zeta potential of 1.0 mV. According to the condensation data, these dendriplexes are probably diffuse and less compact than the triazine dendriplexes and are therefore not suitable for systemic application.

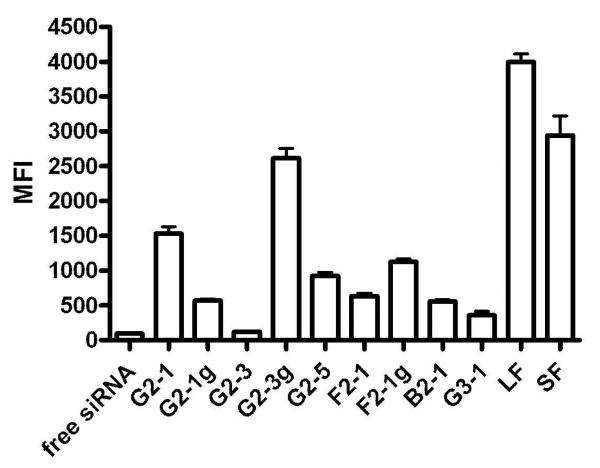

Uptake Efficiency

Based on the results from flow cytometry, the uptake study clearly revealed strong differences in the amount of siRNA being taken up into the cell as a result of the different carrier, as can be seen in Figure 5. Since trypan blue was used to quench all fluorescence on the cell surface, only fluorescent signals inside the cells were measured. As controls, the commercially available transfection reagents Lipofectamine™2000 (LF) and SuperFect™ (SF) were used, where LF is a cationic lipid-based reagent and SF is a generation 4 “fractured” PAMAM.40 Both commercially available reagents lead to strong uptake of fluorescently labeled siRNA into the cells. G2-1 only delivered 38 % of the amount of siRNA into the cells as compared to LF, which performed best among the reagents tested. G2-1g showed reduced uptake as compared to G2-1, which may be explained by the lower zeta potential. G2-3 did not efficiently deliver siRNA since the fluorescence measured was comparable to cells which had been treated with free siRNA only. This result was not surprising, considering the poor complexation and rapid release of siRNA in the presence of very low concentrations of competing anions. Cells transfected with G2-3g dendriplexes exhibited the highest fluorescence among the triazine dendriplex-treated cells. The amount of siRNA inside the cells was 65% of the amount delivered by LF. This very effective delivery can certainly be attributed to the very small size of G2-3g dendriplexes. It has to be kept in mind, however, that the sizes measured in 5 % glucose solution are expected to be larger in cell culture medium or in vivo. G2-5 dendriplexes, however, did not perform as well despite their similar size. A possible explanation for this rather surprising behavior is that the fluorescence inside the G2-5 dendriplexes is strongly quenched, as observed in the heparin displacement assay. It is possible that four hours after transfection, siRNA was not yet released from the dendriplexes. Another reason for the low fluorescence measured might be that the amphiphilic dendrimer has changed the membrane properties of the transfected cells and therefore enabled trypan blue to reach the cytosol, quenching the fluorescent siRNA. F2-1 and F2-1g dendriplexes showed comparably low uptake efficiency which may be caused by their larger size or in the case of F2-1 due to its rather low stability as shown in the heparin displacement assay. Cells transfected with B2-1 and G3-1 dendriplexes exhibited the lowest uptake despite good and comparable stability of the complexes. Their failure to efficiently deliver siRNA into the cells may therefore be attributed to their sizes. As previously reported, a size of around 150 nm seems to be the limit for successful cellular uptake of siRNA complexes.10

Figure 5.

Cellular uptake of dendriplexes made of Alexa488-labeled siRNA into HeLa/Luc cells after four hours of incubation as measured by flow cytometry.

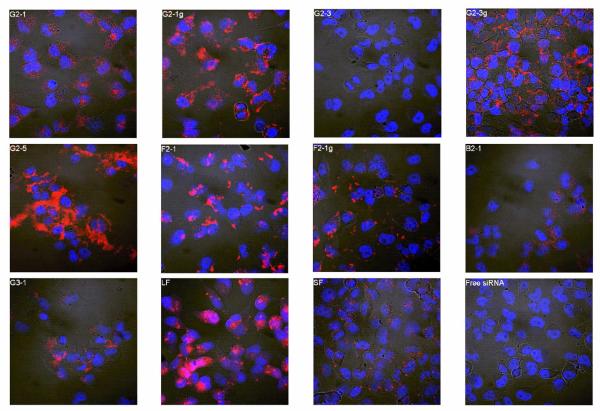

Subcellular Distribution

Since both the amount of siRNA taken up as well as their subcellular distribution play a critical role in the transfection efficacy of dendriplexes, confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed to detect differences in subcellular distribution resulting from the structure of the triazine dendrimers used as the carrier. Representative images of each treatment group are given in Figure 6. Dendriplexes formed with G2-1 seemed to be taken up only to a low extent, which corroborates well with the flow cytometry data. Although the latter study had revealed only very little uptake of G2-1g dendriplexes, nonetheless, evenly distributed fluorescence was observed in the cytoplasm by confocal microscopy. siRNA complexed with G2-3 was not taken up, as already shown by flow cytometry, whereas G2-3g dendriplexes, which revealed the most promising results in the uptake study, were retrieved to a large extent in the cytosol of the transfected cells. G2-3 had been one of the least toxic dendrimers in our earlier study, due to the low density of primary amines.29 Reduction in cytotoxicity, however, is often linked to reduced uptake, as shown with acetylated PAMAM derivatives. These dendrimers lost the ability to reduce GFP expression when complexed with the appropriate siRNA, due to reduced cellular uptake.24 While this problem of reduced cellular uptake could be improved by quaternization of the internal amines to increase cationic charge at physiological pH25, we show the same improvement upon guanidinylation, which also leads to stronger protonation of the dendrimer due to the higher pKa of guanidium groups (pKa around 13) compared to primary amines (pKa around 10). Alternatively, Minko, et al. synthesized internally cationic and hydroxyl-terminated PAMAM G4 dendrimers,26 which we have mimicked by introducing both hydroxyl groups and protonable groups in the periphery of our triazine dendrimers. When transfected with the alkylated dendrimer G2-5, fluorescently labeled siRNA was spread throughout the cells. This suggests that even four hours after treatment, the complexes are readily released from the endosomal environment, and fluorescent siRNA is released. It is possible that the uptake mechanism for alkylated dendriplexes are different from the uptake mechanisms by which less amphiphilic dendriplexes are taken up. In an earlier study, Kono et al. attributed the high transfection efficiency of phenylalanine-modified PAMAM to the ability of the hydrophobic amino acid to interact with the hydrophobic portions of the cell membrane and cause its destabilization, thus increasing the translocation of the complex.41 This same interaction may result in the high intracellular distribution of the alkylated triazine dendrimer G2-5, but may also disrupt or disturb the cell membranes, leading to diffusion of trypan blue into the cytosol in the uptake study. In this case, it would have to be investigated, if the cell membrane disturbance is only transient or rather severe, leading to necrosis of the cells. Dendriplexes made of F2-1 were found to be bound to the outer cell membrane, and F2-1g dendriplexes appeared to be trapped in the endo-lysosomal compartment, suggesting that these complexes may not result in high levels of gene knockdown as their load may not be readily incorporated into the RISC in the cytosol for biological activity. Incomplete release of the siRNA inside the cells is a well known hurdle in efficient siRNA delivery and has been reported to limit the biological activity of both PAMAM and Tat-conjugated PAMAM.23 B2-1 and G3-1 delivered very little siRNA into the cells, as already observed by flow cytometry. Interestingly, siRNA formulated with LF was retrieved both widely distributed and in vesicles. It is therefore possible that at four hours after transfection not all the lipoplexes have released their load. Cells transfected with SF dendriplexes exhibited a very interesting subcellular distribution pattern. Tiny fluorescent dots were found inside the cells and membrane-bound. Since the uptake study revealed high intracellular fluorescence (74% of LF), a considerable amount of siRNA must however be delivered into the cells after four hours.

Figure 6.

Confocal images showing the subcellular distribution of dendriplexes made of Tye543-labeled siRNA (red) following cellular uptake in HeLa/Luc cells 4 hours after transfection. DAPI-stained nuclei are shown in blue.

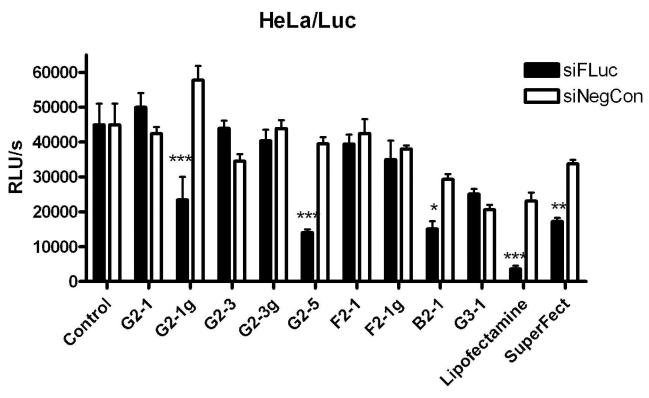

Transfection Efficiency

After clarification of the relationships between the physicochemical properties of triazine dendriplexes and their uptake behavior, their biological activity was measured in vitro. Both commercially available transfection reagents (LF and SF) mediated specific and significant (***p< 0.001 and **p< 0.01) luciferase knock down, but also showed measureable off-target effects in cells treated with lipo-/dendriplexes with the negative control sequence, as shown in Figure 7. These off-target effects have been shown to be problematic for other dendrimer systems, including PAMAM42 and PPI43 and are most commonly caused by toxicity of the transfection reagent. SuperFect™ was originally designed as a DNA transfectant, however Superfect/siRNA dendriplexes have previously been described to successfully knock down the expression of Erbin in rat cheochromocytoma cells (PC12), resulting in a 52% enhancement of NGF-mediated differentiation.22 Other modifications of PAMAM such as Tatconjugation of PAMAM G5 dendrimers only lead to modest gene knockdown at higher dendrimer concentrations.23 In our study, the most potent triazine dendrimer formulations for specific and significant (***p< 0.001) RNAi were the rigid, guanidinylated dendriplexes G2-1g and the alkylated dendriplexes G2-5. In the case of G2-5, the high knockdown efficiency most likely results from favorable intracellular distribution as well as the small complex size. G2-1g complexes were more effective than G2-3g dendriplexes concerning in vitro RNAi although G2-3g had shown the highest uptake efficiency due to its small size. Since G2-1g, however, had revealed a more uniform intracellular siRNA distribution, it is possible that siRNA complexed with G2-3g was less available for incorporation into the RISC than siRNA delivered by G2-1g. The amine analogue of this dendrimer, G2-1, did not exhibit gene knockdown capacity, which is in line with the poor and diffuse subcellular presence of siRNA. It should be mentioned that all triazine dendrimers, except for B2-1 and G3-1 exhibited less off-target effects than the commercially available transfection reagents. The flexible dendrimers F2-1 and F2-1g, and the higher generation dendrimer G3-1 all showed markedly reduced siRNA transfection efficiency as compared to the previously mentioned rigid analogues. This may result from a variety of factors. The flexible dendrimers F2-1 and F2-1g both formed relatively large complexes compared to the most successful dendriplexes G2-1g and G2-5. Based on the CLSM images, these dendriplexes were not readily translocated into the cytosol, probably due to entrapment in endosomes or insufficient uptake of the large complexes that made them unsuitable for RNAi within the cytoplasm. In a study by Peng, et al., knockdown of the Hsp27 gene in human prostate cancer cells (PC-3) was successfully achieved upon transfection with PAMAM dendrimers (G4-G7) in which a triethanolamine core was introduced to increase flexibility.27 In their study, the toxicity of the higher generation PAMAM structures was reduced by the flexible core. However, our “flexible” F2-1 dendrimer showed higher toxicity than the “rigid” G2-1 analogue28 and less interaction with siRNA than the “rigid” alkylated structure G2-539, indicating that F2 dendrimers, which are more successful than PEI 25k in DNA delivery,28 are not suitable for siRNA transfections. G3-1 dendriplexes were the least effective in uptake, as clearly shown by the flow cytometry results. In addition, despite the low cellular uptake, these dendriplexes showed strong off-target effects, as observed with LF. The lack of knockdown efficiency may be due, in part, to higher cytotoxicity28 as well as poor intracellular distribution. As a result these three structures were not suitable candidates for siRNA delivery. The bow-tie dendrimer B2-1 interestingly did display low but significant (*p< 0.05) and specific luciferase knockdown efficiency despite low uptake efficiency and large complex sizes. This low knockdown efficiency most likely results from a very small number of dendriplexes which successfully reached the cytoplasm.

Figure 7.

Knockdown of luciferase expression by dendrimer-siRNA complexes in HeLa/Luc cells. Specificity of knockdown is maintained by comparison to effects of dendriplexes with the negative control sequence siNegCon. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

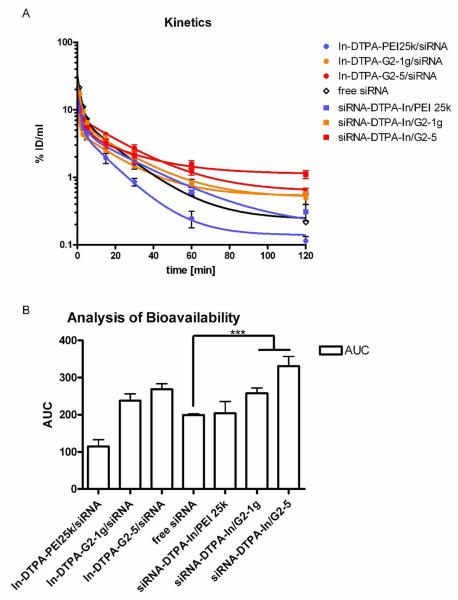

Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution

The two dendrimer formulations G2-1g and G2-5 which were the most successful concerning in vitro knockdown efficiency were subsequently tested in vivo to evaluate their circulation times and deposition behavior as compared to polyplexes of PEI 25k. Thus, both vector and payload were radiolabeled, and dendriplexes were formed with either radiolabeled siRNA or radiolabeled dendrimer to distinguish between the behavior of vector and payload and to test for their in vivo stability. The DTPA coupling degree of siRNA was 74 % of the antisense strands, while the coupling degree of the dendrimers was 0.2 % of the peripheral amines. Expressed in DTPA, 1.85 nmol DTPA was attached to 2.5 nmol siRNA, and 1.5 nmol DTPA was coupled to 780 amines present in the dendriplex. As measured by gamma scintillation counting of blood samples (Figure 8A), dendriplexes made of both the guanidinylated dendrimer G2-1g (orange lines) and the alkylated dendrimer G2-5 (red lines) were stable in vivo for at least 60 minutes. Although G2-5 dendriplexes were most stable in the heparin displacement assay, G2-1g dendriplexes showed longer lasting stability in vivo, reflected in the comparable pharmacokinetic profiles of vector and payload over the complete study of 120 minutes. G2-5 dendriplexes, however, showed slight dissociation after 60 minutes. Both dendriplexes performed much better than polyplexes made of PEI. As previously described, these polyplexes dissociate upon liver passage with the polymer being deposited in the liver and the siRNA being excreted.31 Free 2′-O-Me-siRNA showed rapid clearance from the blood pool, as previously reported for native siRNA.44 While PEI 25k (Figure 8A, blue line, circles) was cleared more readily, which can be explained by its strong first-pass effect in the liver,31, 45 2′-O-Me siRNA complexed with PEI 25k (Figure 8A, blue line, squares) showed the same pharmacokinetic profile as free siRNA, indicating that it was displaced from the complexes. This observation is in line with the low stability of PEI polyplexes described in the heparin displacement assay and in our previous results.31 On the other hand, siRNA that was complexed with dendrimers exhibited longer circulation times than free and PEI-complexed siRNA, emphasizing the in vivo stability of the dendriplexes. To quantify the differences in the circulation times and bioavailability of each vector and load, the areas under the curves (AUCs) were calculated as shown in Figure 8B. Statistical analysis of the values revealed that siRNA complexed with both dendrimers has significantly (***p<0.001) elevated circulation times and bioavailability compared to free or PEI-complexed siRNA.

Figure 8A.

Pharmacokinetics of vector and payload of siRNA-dendriplexes and polyplexes as measured by gamma scintillation counting of blood samples. 8B. Statistical analysis of the bioavailability of vector and load as measured by the area under the curve (AUC). ***p< 0.001

Additionally, the deposition of dendriplexes in comparison to free siRNA and PEI polyplexes was investigated two hours after injection as shown in Figure 9. Interestingly, dendriplexes accumulated to a much lesser extent in the liver as compared to PEI polyplexes. Both dendriplexes showed passive lung targeting, with 47% of the injected dose of dendrimer G2-5 and 32% of the injected dose of G2-1g retrieved by the lung. The G2-5 dendriplexes seemed to dissociate especially in the lung since only 13% of the payload (compared to 47 % of the vehicle) was found in the lung. G2-1g exhibited similar instability with 20% of the complexed siRNA being delivered to the lung in comparison to 32% of the dendrimer. This behavior explains the differences of the pharmacokinetic profiles of G2-5 dendriplexes and is similar to the dissociation of PEI complexes in the liver.31 Passive lung targeting has been described for cationic lipid/DNA complexes many years ago and has been attributed to result from interactions between cationic complexes and anionic serum proteins.

Figure 9.

Biodistribution of vector and payload of siRNA-dendriplexes and polyplexes 2 hours after i.v. administration as measured by gamma scintillation counting of dissected organs.

The nano-sized complexes subsequently form aggregates, leading to temporary deposition in the capillary beds of the lung and possibly transient emboli in the lung microvasulature.46 Lung deposition and efficient transfection of alveolar cells, including pneumocytes, upon systemic administration of polyplexes has been reported for linear PEI47 while branched PEI is not capable of providing highly efficient gene delivery to lungs upon systemic administration.48 In this context, no correlation between complement activation and the determination of the deposition pattern of DNA complexes could be demonstrated.46 Since erythrocyte aggregation was shown to be lower for all triazine dendrimers than for PEI,28 this property cannot serve as an explanation for the extensive lung targeting of the dendriplexes. Concerning branched PEI, we could not observe beneficial properties of polyplexes made of 2′-O-Me siRNA compared to complexes made of native siRNA31 since 36% of the polymer accumulated in the liver compared to only 12% of the PEI-complexed siRNA. Dendriplexes, which were only captured at 15 % in the liver, seemed to be deposited as intact complex with comparable amounts of payload and vector. Free 2′-O-Me siRNA was mostly cleared by the kidneys and considerable amounts were found in the urine (data not shown), but interestingly 19% of the administered dose was excreted hepatobiliarily and was found in the bowel. This is possibly a result of interaction of the amphiphilic siRNA with bile salts or lipoproteins in the blood as reported earlier.49 The renal clearance varied strongly due to differences in the filling level of the bladder 2 hours after injection.

The biodistribution was additionally detected non-invasively by SPECT imaging where strong accumulation in the lung and articulate signals in the liver were detected in all animals treated with dendriplexes (Supporting Information S1 and S2). The SPECT image of a mouse injected with G2-1g dendriplexes (Supporting Information S1) also showed clearance via bowel and bladder, whereas G2-5 dendriplexes seemed to be cleared mainly via the bowel. All SPECT images corroborated well with the results from the dissected organs.

To investigate at which time point the dendriplex accumulations occurred and if a secondary redistribution of dendriplexes follows a primary deposition in the lungs, as assumed for PEI/pDNA complexes,45, 50 perfusion life imaging of mice injected underneath the camera was performed. The time course of biodistribution was analyzed on the basis of regions of interest (ROIs) placed in the lung, the bladder and the mediastinal region, which served for quantification of activity in the blood pool. The analysis of the real-time imaging shows almost no changes in activity in the blood pool since the amount of radioactivity is low compared to the counts measured in the lung. Only a very slight decrease of activity in the lung and a slight increase in the bladder could be observed. The increase of activity in the bladder was stronger in mice treated with G2-1g dendriplexes, which can be explained by the better water solubility of this dendrimer, also shown in the SPECT image (Supporting Information S1). The activity in the blood pool drops to 14% in mice treated with G2-1g dendriplexes and to 36% in mice treated with G2-5 during the first 6 minutes compared to the first signal measured (Supporting Information S3-S5). These findings corroborate the pharmacokinetics study, whereas in the latter one no values are available for t=0. With this perfusion study, we were able to show rapid lung targeting and to rule out secondary redistribution during the first 20 minutes after injection.

Cellular Tissue Distribution of in vivo Transfected Cells

Since in vivo instability and premature unpackaging of electrostatically formed complexes is a major hurdle for efficient in vivo intracellular delivery,51 cellular distribution of siRNA after intravenous administration of dendriplexes was investigated in organ slices of the main target organs exposed by the biodistribution study, namely the lung and the liver. Since temporary deposition of lipoplexes in the capillary beds of the lung has been reported to cause transient emboli in the lung microvasulature,46 lung (and liver) deposition was investigated 2 and 24 hours after injection. Interestingly, fluorescent siRNA was mostly found in the alveolar tissue and alveolar macrophages, rather than in bronchiolar tissue, as shown in Figure 10. We therefore hypothesize that the dendriplexes crossed the alveolar-capillary barrier. siRNA complexed with G2-5 was taken up into the cells to a greater extent than siRNA in G2-1g dendriplexes, although the total amount of siRNA targeted to the lung was greater for G2-1g than for G2-5. This on the one hand illustrates the importance of distribution at the cellular level and on the other hand indicates that the amphiphilic modification of dendrimer G2-5 was favorable for intracellular uptake. The amount of siRNA present in the lung tissue still seemed to be higher in animals treated with G2-5 dendriplexes 24 hours after administration, whereas in both groups of animals the size of the fluorescent dots decreased, suggesting that the siRNA has been partially eliminated and possibly degraded. The amount of fluorescent siRNA retrieved in the liver sections was also greater in animals treated with G2-5 dendriplexes compared to the G2-1g treatment group. However, neither the amount nor the morphology of the fluorescent dots in the liver seemed to be influenced by the time point. Interestingly, some of the siRNA found in the liver was not internalized into liver cells but was present in the bile ducts. This is perfectly in agreement with our assumption of hepatobiliary clearance of part of the siRNA.

Figure 10.

Subcellular distribution of dendriplexes made of Tye543-labeled siRNA (red) in the lung and liver following i.v. administration. DAPI-stained nuclei are shown in blue.

Conclusions

It is well understood that the differences in the molecular topology and location for mechanism of action for DNA and siRNA transfection differ, and as a result, carrier vectors that excel in pDNA transfection may result in poor RNAi. Based on the results from this study it has become clear that triazine dendrimers follow this trend. In previous studies it was shown that surface group manipulations have a moderate effect on pDNA transfection efficiency,29 while increasing the flexibility of the core substantially improves gene transfer.28 However, these same trends are nearly the opposite for siRNA transfection. While F2-1, the most effective DNA delivery vector of the triazine dendrimers investigated28, 29 was not able to mediate RNAi, the rigid triazine dendrimers G2-1g and G2-5 which were only moderately effective gene delivery vectors29 were the most promising for in vitro siRNA delivery. In this study, the interplay of a number of characteristics such as stability, size, surface charge and uptake efficiency was shown. It must be noted that the triazine dendriplexes that were the most effective at gene knockdown showed favorable intracellular distribution, suggesting that this factor may be the most accurate predictor in determining the effectiveness of triazine-based dendriplexes in RNAi. Previous studies have proven an inverse correlation between complex size and level of gene knockdown. However, this trend did not appear to be the most influential parameter in our study. With respect to in vivo siRNA applications, both dendriplexes tested in our study efficiently mediated intracellular siRNA delivery in the lung, indicating that these formulations may be promising nanomedicines for post-transcriptional gene regulation in lung diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Thomas Behr (Nuclear Medicine Department, University Hospital Marburg) for the generous use of equipment and facilities, to Eva Mohr, Klaus Keim (Dept. of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmacy), Viktoria Morokina (Institute of Pathology), and Ulla Cramer (Dept. of Nuclear Medicine) for excellent technical support. MEDITRANS, an Integrated Project funded by the European Commission under the Sixth Framework (NMP4-CT-2006-026668), is gratefully acknowledged. EES and MAM thank the N.I.H. (R01 GM 65460).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Two animated gif files of SPECT images, two planar gamma camera images of the perfusion studies and their analysis, the description of the synthetic procedure that yielded dendrimer F2-1g and the analytic data can be downloaded online. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Milhavet O, Gary DS, Mattson MP. Pharma. Rev. 2003;55:629–648. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilmore IR, Fox SP, Hollins AJ, Sohail M, Akhtar S. J. Drug Target. 2004;12:315–340. doi: 10.1080/10611860400006257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bumcrot D, Manoharan M, Koteliansky V, Sah DWY. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:711–719. doi: 10.1038/nchembio839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li CX, Parker A, Menocal E, Xiang S, Borodyansky L, Fruehauf JH. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2103–2109. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue A, Sawata SY, Taira K. J. Drug Target. 2006;14:448–455. doi: 10.1080/10611860600845397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akhtar S, Benter I. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007;59:164–182. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagerman PJ. Flexibility of DNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1988;17:265–268. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kebbekus P, Draper DE, Hagerman P. Persistence length of RNA. Biochemistry. 1995;34(13):4354–4357. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mok H, Lee SH, Park JW, Park TG. Multimeric small interfering ribonucleic acid for highly efficient sequence-specific gene silencing. Nat Mater. 9(3):272–278. doi: 10.1038/nmat2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grayson ACR, Doody AM, Putnam D. Biophysical and structural characterization of polyethylenimine-mediated siRNA delivery in vitro. Pharmaceutical Research. 2006;23(8):1868–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamore PD, Haley B. Ribo-gnome: the big world of small RNAs. Science. 2005;309(5740):1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gary DJ, Puri N, Won YY. Polymer-based siRNA delivery: perspectives on the fundamental and phenomenological distinctions from polymer-based DNA delivery. J Control Release. 2007;121(1-2):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grayson AC, Ma J, Putnam D. Kinetic and efficacy analysis of RNA interference in stably and transiently expressing cell lines. Mol Pharm. 2006;3(5):601–13. doi: 10.1021/mp060026i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseng S.-j., Tang S-C. Development of Poly(amino ester glycol urethane)/siRNA Polyplexes for Gene Silencing. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18(5):1383–1390. doi: 10.1021/bc060382j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manoharan M. RNA interference and chemically modified small interfering RNAs. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2004;8(6):570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber N, Ortega P, Clemente MI, Shcharbin D, Bryszewska M, Mata F. J. d. l., Gomez R, Munoz-Fernandez MA. Characterization of carbosilane dendrimers as effective carriers of siRNA to HIV-infected lymphocytes. Journal of Controlled Release. 2008;132:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gras R, Almonacid L, Ortega P, Serramia MJ, Gomez R, Mata F. J. d. l., Lopez-Fernandez LA, Munoz-Fernandez MA. Changes in gene expression pattern of human primary macrophages induced by carbosilane dendrimer 2G-NN16. Pharmaceutical Research. 2009;26(3):577–586. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9776-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posadas I, Lopez-Hernandez B, Clemente MI, Jimenez JL, Ortega P, Mata J. d. l., Gomez R, Munoz-Fernandez MA, Cena V. Highly efficient transfection of rat cortical neurons using carbosilane dendrimers unveils a neuroprotective role for HIF-1alpha in early chemical hypoxia-mediated neurotoxicity. Pharmaceutical Research. 2009;26(5):1181–1191. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9839-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omidi Y, Hollins AJ, Drayton RM, Akhtar S. Polypropylenimine dendrimer-induced gene expression changes: the effect of complexation with DNA, dendrimer generation and cell type. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2005;13(7):431–443. doi: 10.1080/10611860500418881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue Y, Kurihara R, Tsuchida A, Hasegawa M, Nagashima T, Mori T, Niidome T, Katayama Y, Okitsu O. Efficient delivery of siRNA using dendritic poly(L-lysine) for loss-of-function analysis. Journal of Controlled Release. 2008;126:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsubouchi A, Sakakura J, Yagi R, Mazaki Y, Schaefer E, Yano H, Sabe H. Localized suppression of RhoA activity by Tyr31/118-phosphorylated paxillin in cell adhesion and migration. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159(4):673–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang YZ, Zang M, Xiong WC, Luo Z, Mei L. Erbin suppresses the MAP kinase pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(2):1108–1114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang H, DeLong R, Fisher MH, Juliano RL. Tat-conjugated PAMAM dendrimers as delivery agents for antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. Pharmaceutical Research. 2005;22(12):2099–2106. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-8330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waite CL, Sparks SM, Uhrich KE, Roth CM. Acetylation of PAMAM dendrimers for cellular delivery of siRNA. BMC Biotechnology. 2009;9(38) doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patil ML, Zhang M, Betigeri S, Taratula O, He H, Minko T. Surface-modified and internally cationic polyamidoamine dendrimer for efficient siRNA delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19(7):1396–1403. doi: 10.1021/bc8000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil ML, Zhang M, Taratula O, Garbuzenko OB, He H, Minko T. Internally cationic polyamidoamine PAMAM-OH dendrimers for siRNA delivery: effect of the degree of quaternization and cancer targeting. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10(2):258–266. doi: 10.1021/bm8009973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X.-x., Rocchi P, Qu F.-q., Zheng S.-q., Liang Z.-c., Gleave M, Iovanna J, Peng L. PAMAM dendrimers mediate siRNA delivery to target Hsp27 and produce potent antiproliferative effects on prostate cancer cells. ChemMedChem. 2009 doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merkel OM, Mintzer MA, Sitterberg J, Bakowsky U, Simanek EE, Kissel T. Triazine dendrimers as nonviral gene delivery systems: effects of molecular structure on biological activity. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20(9):1799–806. doi: 10.1021/bc900243r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mintzer MA, Merkel OM, Kissel T, Simanek EE. Polycationic triazine-based dendrimers: effect of peripheral groups on transfection efficiency. New J Chem. 2009;33:1918–1925. doi: 10.1039/b908735d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merkel OM, Beyerle A, Librizzi D, Pfestroff A, Behr TM, Sproat B, Barth PJ, Kissel T. Nonviral siRNA delivery to the lung: investigation of PEG-PEI polyplexes and their in vivo performance. Mol Pharm. 2009;6(4):1246–60. doi: 10.1021/mp900107v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merkel OM, Librizzi D, Pfestroff A, Schurrat T, Buyens K, Sanders NN, De Smedt SC, Behe M, Kissel T. Stability of siRNA polyplexes from poly(ethylenimine) and poly(ethylenimine)-g-poly(ethylene glycol) under in vivo conditions: effects on pharmacokinetics and biodistribution measured by Fluorescence Fluctuation Spectroscopy and Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) imaging. J Control Release. 2009;138(2):148–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Germershaus O, Mao S, Sitterberg J, Bakowsky U, Kissel T. Gene delivery using chitosan, trimethyl chitosan or polyethylenglycol-graft-trimethyl chitosan block copolymers: establishment of structure-activity relationships in vitro. J Control Release. 2008;125(2):145–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merkel OM, Librizzi D, Pfestroff A, Schurrat T, Behe M, Kissel T. In vivo SPECT and real-time gamma camera imaging of biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of siRNA delivery using an optimized radiolabeling and purification procedure. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20(1):174–82. doi: 10.1021/bc800408g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang M, Redemann CT, S. FC., Jr. In vitro gene delivery by degraded polyamidoamine dendrimers. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 1996;7(6):703–714. doi: 10.1021/bc9600630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izumrudov VA, Bronich TK, Novikova MB, Zezin AB, Kabanov VA. Substitution reactions in ternary systems of macromolecules. Polymer Science U.S.S.R. 1982;24(2):367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bronich T, Kabanov AV, Marky LA. A Thermodynamic Characterization of the Interaction of a Cationic Copolymer with DNA. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2001;105(25):6042–6050. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolcato-Bellemin AL, Bonnet ME, Creusat G, Erbacher P, Behr JP. Sticky overhangs enhance siRNA-mediated gene silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(41):16050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707831104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aissaoui A, Oudrhiri N, Petit L, Hauchecorne M, Kan E, Sainlos M, Julia S, Navarro J, Vigneron JP, Lehn JM, Lehn P. Progress in gene delivery by cationic lipids: guanidinium-cholesterol-based systems as an example. Curr Drug Targets. 2002;3(1):1–16. doi: 10.2174/1389450023348082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pavan G, Mintzer MA, Simanek EE, Merkel OM, Kissel T, Danani A. Computational Insights into the Interactions between DNA and siRNA with “Rigid” and “Flexible” Triazine Dendrimers. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11(3):721–30. doi: 10.1021/bm901298t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang MX, Redemann CT, Szoka FC., Jr. In vitro gene delivery by degraded polyamidoamine dendrimers. Bioconjug Chem. 1996;7(6):703–14. doi: 10.1021/bc9600630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kono K, Akiyama H, Takahashi T, Takagishi T, Harada A. Transfection activity of polyamidoamine dendrimers having hydrophobic amino acid residues in the periphery. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(1):208–14. doi: 10.1021/bc049785e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hollins AJ, Omidi Y, Benter IF, Akhtar S. Toxicogenomics of drug delivery systems: exploiting delivery system-induced changed in target gene expression to enhance siRNA activity. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2007;15(1):83–88. doi: 10.1080/10611860601151860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Omidi Y, Hollins AJ, Drayton RM, Akhtar S. Polypropylenimine dendrimer-induced gene expression changes: the effect of complexation with DNA, dendrimer generation, and cell type. Journal of Drug Targeting. 2005;13(7):431–443. doi: 10.1080/10611860500418881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dykxhoorn DM, Palliser D, Lieberman J. The silent treatment: siRNAs as small molecule drugs. Gene Ther. 2006;13(6):541–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merdan T, Kunath K, Petersen H, Bakowsky U, Voigt KH, Kopecek J, Kissel T. PEGylation of poly(ethylene imine) affects stability of complexes with plasmid DNA under in vivo conditions in a dose-dependent manner after intravenous injection into mice. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16(4):785–92. doi: 10.1021/bc049743q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barron LG, Meyer KB, Szoka FC., Jr. Effects of complement depletion on the pharmacokinetics and gene delivery mediated by cationic lipid-DNA complexes. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9(3):315–23. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.3-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou S-M, Erbacher P, Remy J-S, Behr J-P. Systemic linear polyethylenimine (L-PEI)-mediated gene delivery in the mouse. The Journal of Gene Medicine. 2000;2(2):128–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(200003/04)2:2<128::AID-JGM95>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goula D, Benoist C, Mantero S, Merlo G, Levi G, Demeneix BA. Polyethylenimine-based intravenous delivery of transgenes to mouse lung. Gene Ther. 1998;5(9):1291–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeong JH, Mok H, Oh Y-K, Park TG. siRNA Conjugate Delivery Systems. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2008;20(1):5–14. doi: 10.1021/bc800278e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishiwata H, Suzuki N, Ando S, Kikuchi H, Kitagawa T. Characteristics and biodistribution of cationic liposomes and their DNA complexes. J Control Release. 2000;69(1):139–48. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burke RS, Pun SH. Extracellular barriers to in Vivo PEI and PEGylated PEI polyplex-mediated gene delivery to the liver. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19(3):693–704. doi: 10.1021/bc700388u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.