Abstract

The anaphase promoting complex (APC) or cyclosome is a multi-subunit E3 ubiquitin ligase. Cdc20 [fizzy (fzy), or p55CDC] and Cdh1 [Hct1, srw1, or fizzy-related 1 (fzr1)] encode two adaptor proteins that bring substrates to APC. Both APC-Cdc20 and APC-Cdh1 are implicated in the control of mitosis through mediating ubiquitination of mitotic regulators such as cyclin B1 and securin. However, the importance of the function of Cdh1 in vivo and whether its function is redundant with that of Cdc20 are unclear. We report here the analysis of mice lacking Cdh1. We show that Cdh1 is essential for placenta development and its deficiency causes early lethality. Cdh1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts entered replicative senescence prematurely due to stabilization of Ets2 and subsequent activation of p16Ink4a expression. These results uncovered an unexpected role of APC in maintaining replicative life span of murine embryonic fibroblasts. Further, Cdh1 heterozygous mice display defects in late-phase long-term potentiation (L-LTP) in the hippocampus and are deficient in contextual fear conditioning, suggesting a role of Cdh1 in learning and memory.

We previously showed that Cdc20 is essential for mitosis and its absence is not compensated by Cdh1 1. To determine if Cdh1 is required for mitosis and to delineate the in vivo function of Cdh1, we derived mice from a gene-trap mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell clone (RRJ067) isolated by BayGenomics 2. The gene-trap construct, containing splicing acceptor and β-geo, was inserted in intron 5 of Cdh1 (Fig. S1a). The insertion should fuse the N-terminal 128 amino acid residues with β-geo, generating a dysfunctional allele of Cdh1. We named this allele as Cdh1gt (gt denotes gene-trap). It was successfully transmitted through germline (Fig. S1b). Western blot analysis of E9.5 whole embryo lysates demonstrated the absence of Cdh1 protein in Cdh1gt-gt embryos and an approximately 50% reduction in heterozygous embryos (Fig. S1c). Taking advantage of the gene-trap, we analyzed the expression of Cdh1 through a colorimetric assay for LacZ. As shown in Fig. S1d, Cdh1 is widely expressed through out the whole embryo.

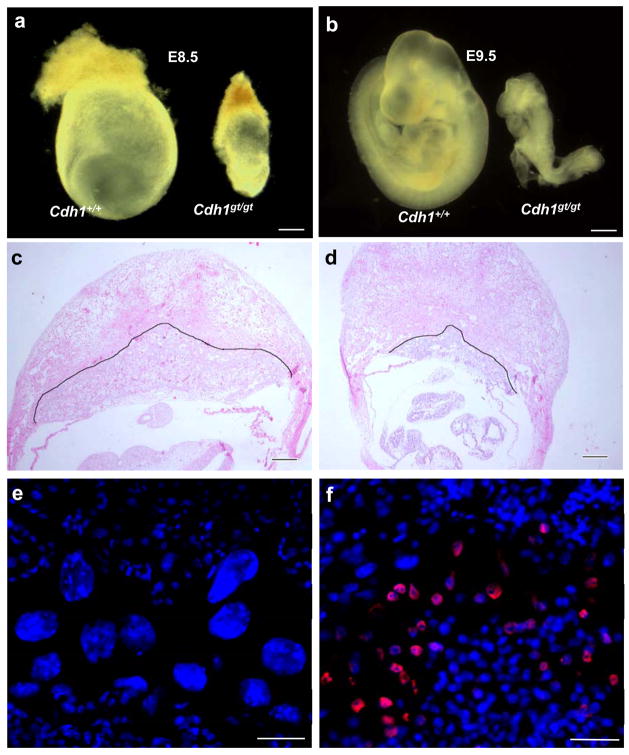

To determine whether Cdh1 is required for development, we intercrossed the heterozygous mice. Repeated breeding failed to produce animals that were Cdh1gt/gt, indicating that the homozygous mice either died in utero or died shortly after birth. Analysis of embryos at different stages of development indicated that the homozygous mutants died around E9.5 (Fig. 1 a and b). At E9.5, the mutant embryos were much smaller than controls and were delayed in development about a day (Fig. 1b). No live Cdh1-deficient embryos were recovered beyond E9.5. These results indicate that Cdh1 deficiency causes early embryonic lethality.

Figure 1.

Absence of Cdh1 causes early lethality in mice. a and b. Retarded development of Cdh1gt/gt embryos at E8.5 and E9.5 c and d. H&E stained sections of wildtype (c) and mutant (d) E9.5 whole deciduas. The black outline delineates the boundary between deciduous and placental tissues. e and f. Immunostaining of cyclin B1 on wildtype (e) and mutant (f) E9.5 placentas. Scale bars in a and b, 40 μm; in c and d, 20 μm; in e and f, 10 μm.

A common cause of death of early embryos is the dysfunction of the placenta. Therefore, we examined the Cdh1 mutant placenta. At E9.5, the wildtype placenta is well developed (Fig. 1c), whereas the mutant is much smaller and thinner (Fig. 1d). Strikingly, the mutant placenta lacks giant cells (Fig. 1 e and f). Placental giant cells are produced via endoreplication in which cells go through DNA synthesis without mitotic divisions. To make a cell endoduplicate, an inhibition of Cdk1 (hence mitosis) is necessary and sufficient, which could be achieved artificially via blockade of Cdk1 3 or constitutive activation of APC (anaphase promoting complex)-Cdh1 4. It is plausible that endoreplicaiton in giant cells depends on APC-Cdh1 to keep cyclin B1 at low levels. Thus, in the absence of Cdh1, cyclin B1 would accumulate and prevent endoreplication, leading to a failure in the formation of giant cells. To determine if that is the case, we analyzed the expression of cyclin B1 in placenta. As shown in Fig. 1 e and f, cyclin B1 was readily detectable in mutant placenta in an area between maternal and fetal tissues where giant cells should reside. In contrast, no cyclin B1 could be detected in wildtype control. These results indicate that Cdh1 plays an essential role in the endoreplication of placental giant cells. This role is conserved through evolution as Drosophila Fzr1 is also required for the process 5. The lack of giant cells and placental defects are likely the cause of the early lethality of Cdh1 deficient embryos. It is unclear at present whether the placental defects are secondary to the lack of giant cells or Cdh1 is intrinsically required for the development of all the other layers of the placenta. In support of the latter, Cdh1 is highly expressed in whole placenta (Fig. S1e).

The fact that Cdh1-deficient embryos can survive up to 9.5 days indicates that Cdh1 is not essential for cell viability. To examine the function of Cdh1 in cell cycle control, especially in mitosis, we derived mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from E9.5 embryos. The MEFs could be propagated in culture, indicating that Cdh1 is not absolutely required for cell division. We analyzed the distribution of mitotic phases in asynchronously growing MEFs. As shown in Fig. S2a, there were no differences in the proportion of prometaphase, metaphase, and anaphase cells between wildtype and Cdh1gt/gt MEFs. However, we saw a small but significant increase in the proportion of telophase cells in the mutant MEFs. Further, we found that Cdh1gt/gt MEFs contained more than 12% of binucleated cells (vs. less than 2% in wildtype MEFs) (Fig. S2b and c), indicating failure of cytokinesis at certain frequencies when Cdh1 is absent. Taken together, these data indicate that although Cdh1 is not absolutely required for mitosis, its absence does cause some difficulties in completing cell division, causing genome instability manifested as binucleation.

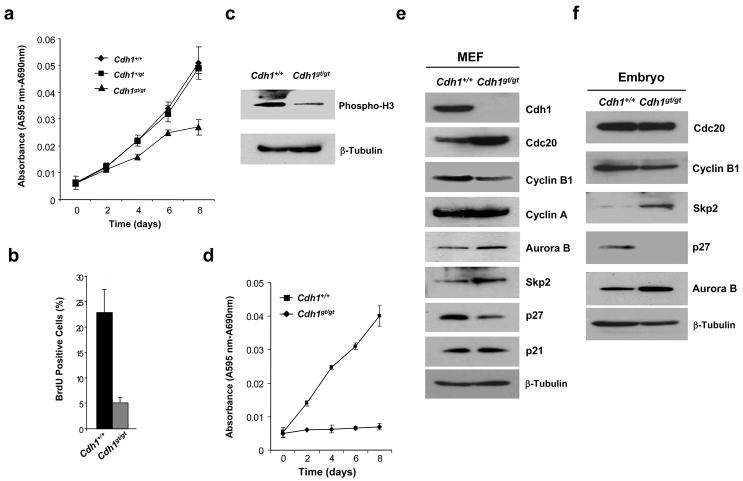

Cdh1gt/gt MEFs grew noticeably slower than the wildtype or heterozygous MEFs soon after isolation (Fig. 2a). BrdU incorporation assay demonstrated a much reduced fraction of mutant MEFs undergoing active DNA synthesis (Fig. 2b). Consequently, we found that the levels of phospho-H3, an indicator of mitotic cells, were much lower in Cdh1gt/gt than in the wildtype MEFs (Fig. 2c). By passage 6, Cdh1gt/gt cells essentially stopped growing, whereas the control was still dividing robustly (Fig. 2d). These data demonstrate that Cdh1 plays an essential role in maintaining the replicative lifespan of MEFs.

Figure 2.

Analyses of Cdh1gt/gt MEFs. a. Growth curve analysis of MEFs at passage 3 (MTT assay). b. BrdU incorporation assays of passage 3 MEFs. c. Immunoblotting of phospho-histone H3 in passage 3 MEFs. d. Growth curve analysis of MEFs at passage 6. e and f. Immunoblotting analysis of various cell cycle regulators in MEFs (e) and E9.0 embryos (f). Results in a, b, and d were from three independent experiments. Error bars are standard deviations.

A number of proteins have been shown to be the substrates of APC-Cdh1, including cyclin B1, Aurora B 6, 7, Plk1 8, Cdc20 9–11, Skp2 9–11, etc. The availability of Cdh1 null cells made it possible to test which of these substrates are only susceptible to APC-Cdh1 mediated ubiquitination, not to that of APC-Cdc20. We performed Western blot analyses of these proteins to determine their levels in asynchronously growing MEFs. As shown in Fig. 2e, Cdc20, Aurora B, and Skp2 were stabilized as expected. Because the increase in Skp2 levels, the level of p27, a substrate of SCFSkp212, 13, decreased. However, another Cdk inhibitor p21Cip1, believed to be Skp2’s substrate as well 14, was maintained at the same level in Cdh1-deficient MEFs as in wildtype cells, suggesting that the increase of p21 levels in the absence of Skp2 might be for other reasons 14. Alternatively, Cdh1 could have a negative, Skp2-unrelated role in maintaining p21 levels so that the net effect is no change. Unexpectedly, the levels of cyclin B1 went down in the absence of Cdh1, whereas there was little change in cyclin A levels. The stabilization of Cdc20 probably fulfilled the mitotic role of Cdh1. However, Cdh1 could not compensate for the absence of Cdc20 1. Similar changes were found in Cdh1 mutant embryos, except that Cdc20 was not significantly increased in the mutant (Fig. 2f). The reason for this is not clear and awaits further investigation.

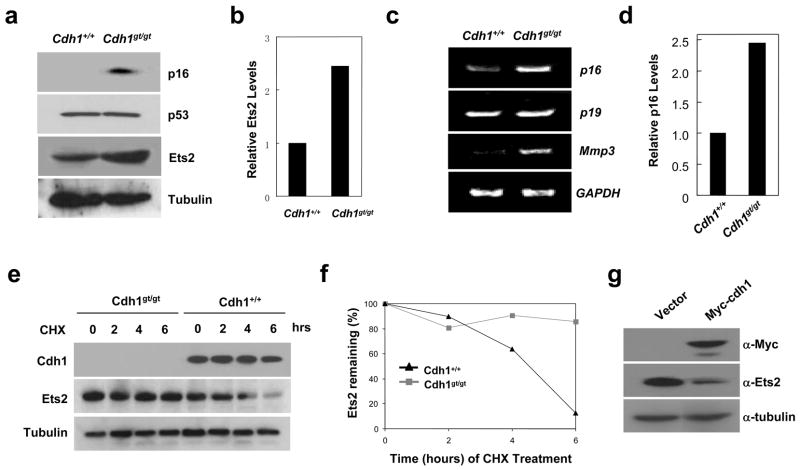

Given the decreased levels of p27 and no change in p21 levels, it was puzzling that Cdh1-deficient MEFs grew slower than control and entered senescence prematurely. We reasoned that the Ink4a family inhibitor p16 might be the culprit since it is associated with senescence. Indeed, we found p16 protein levels were dramatically increased in Cdh1gt/gt MEFs, whereas the other senescence regulator p53 was not (Fig. 3a). The increase in p16 mighty be caused by protein stabilization or enhanced transcription. We analyzed p16 messenger RNA level by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 3c and d, p16 mRNA level was increased in the mutant MEFs. p19Arf, encoded by the same locus, however, was not increased. These results indicate that the absence of Cdh1 activates p16 transcription, leading to the slow growth and senescence.

Figure 3.

Cdh1 regulates the expression of p16 through modulating the stability of Ets2. a. Western blot analysis of p16, p53 and Ets2 in MEFs. b. Quantitation of Ets2 levels in a. c. RT-PCR analysis of gene expression in MEFs. d. Quantitation of p16 levels in c. e. Analysis of Ets2 stability in wildtype and Cdh1 mutant MEFs treated with cyclohexamide (CHX). f. Quantitation of Ets2 levels in e. g. The effect of Cdh1 overexpression on the stability of Ets2 in wildtype MEFs. Full scans of the gels in a, e, and g are presented in supplemental figure 5.

We hypothesized that the increased p16 expression in Cdh1gt/gt MEFs was caused by stabilization of a p16 transcriptional activator. Ets2 is known to activate p16 expression 15. We therefore analyzed its levels in Cdh1gt/gt MEFs to determine if there was an increase to account for the enhanced expression of p16. Indeed, Ets2 was upregulated more than two-fold by Cdh1 deficiency (Fig. 3 a and b). We then measured the halflife of Ets2 in wildtype and Cdh1gt/gt MEFs to determine if the upregulation of this transcription factor is a result of protein stabilization. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3 e and f, Ets2 became stabilized in Cdh1-deficient MEFs. Further, we overexpressed Cdh1 in wildtype MEFs, and found the overexpression could suppress the levels of Ets2 (Fig. 3g).

To demonstrate that Ets2 is indeed responsible for the upregulation of p16 and senescence, we reduced its expression in Cdh1gt/gt MEFs with RNA interference delivered by a retroviral shRNA vector. Ets2 shRNA expression suppressed Ets2 levels about 75% comparing to the control shRNA (Fig. S3 a and b). More importantly, at the same time the expression of p16 also decreased (Fig. S3 a and b) and the cells were able to proliferate again (Fig. S3c). These results indicate that Ets2-mediated transcriptional upregulation of p16 causes the senescence phenotype displayed by Cdh1gt/gt MEFs. In addition, the stabilized Ets2 not only induced more p16 expression but also other Ets2 target genes, for example, Mmp3 (matrix metalloproteases 3) (Fig. 3c).

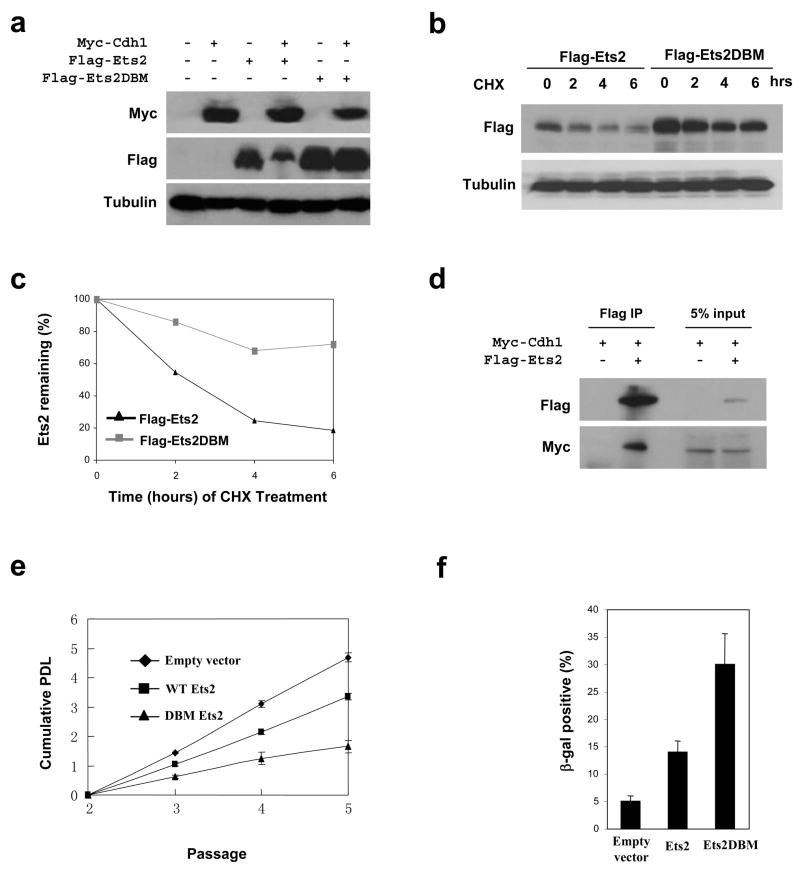

The stabilization of Ets2 in the absence of Cdh1 suggests that it might be a direct substrate of APC-Cdh1. Examination of Ets2 sequence indicated the presence of a putative destruction box at the N-terminus that is conserved between mouse and human (RGTL, residues 20–23 in both human and mouse) but is not present in Ets2’s close homologue Ets1. To determine if this putative D-box mediates Ets2’s destruction, we mutated it to GGTV (Ets2DBM) as has been done on Id2 16, established transient expression of Flag-tagged Ets2 and Ets2DBM in 293T cells which were further transfected with myc-tagged Cdh1 or empty vector, and analyzed the levels of the exogenous Ets2. As shown in Fig. 4a, the expression of myc-Cdh1 greatly inhibited the accumulation of wildtype Ets2 but not that of Ets2DBM. When expressed in HeLa cells, Ets2 and Ets2DBM displayed very different stabilities (Fig. 4 b and c). Moreover, we could detect an interaction between Cdh1 and Ets2 (Fig. 4d). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that Ets2 is a substrate of APC-Cdh1. We also performed in vitro Ets2 ubiquitination assay by APC-Cdh1, but failed to detect ubiquitination on Ets2 (data not shown). It is likely that the in vitro translated Ets2 lacked proper modification (for instance phosphorylation) to be recognized by Cdh1. Alternatively, ubiquitination of Ets2 requires additional factors missing in the in vitro assay system.

Figure 4.

Ets2 is potential substrate of APC-Cdh1. a. Immunoblotting analysis of ETS2 (wildtype and destruction box mutated) in 293T cells transfected with control or Cdh1-expressiong plasmids. b. Analysis of wildtype and destruction box-mutated Ets2 expressed in HeLa cells treated with cyclohexamide (CHX). c. Quantitation of the results in b. c. Ets2 interacts with Cdh1. Myc-Cdh1 and Flag-Ets2 were transiently expressed in 293T cells. Flag-Ets2 was immunoprecipitated and blotted for the presence of Myc-Cdh1. e. Analysis of the effect of Est2 expression on the proliferative potential of wildtype MEFs. f. Quantitation of cells positive for senescence-associated β-galactosidase. Results in e and f were from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Full scans of the gels in a, b, and d are presented in supplemental figure 5.

Cdh1-deficient MEFs have limited ability to proliferate due to the increased levels of Ets2. By overexpressing Ets2 in wildtype MEFs, one would expect to see a reduction in the proliferation potential of these cells and an increase in the number of senescent cells. More importantly, Ets2DBM should be more potent than the wildtype protein in reducing the proliferation and inducing senescence. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 4e, both Ets2 and Ets2DBM suppressed the growth of wildtype MEFs, but with much more suppression rendered by Ets2DBM. We further determined the fraction of senescent cells by assaying senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity in empty vector, Ets2, and Ets2DBM transduced MEFs. It is clear that Est2DBM was much more efficient than Ets2 in inducing senescence (Fig. 4f).

Post-mitotic neurons are one of the major cell types that express Cdh1 17, suggesting that APC-Cdh1 may have functions in the nervous system. We determined the expression pattern of Cdh1 in the adult Cdh1+/gt mouse brain and found that Cdh1 is expressed in almost all neurons (Fig. S4a). No gross morphological changes in the hippocampus or other regions of the brain of Cdh1+/gt mice were apparent, and Western blot analysis demonstrated a reduction in the expression of Cdh1 about 50% in Cdh1+/gt brain when compared to wildtype mice (Fig. S4b). To begin to determine whether the reduction in Cdh1 expression had an impact on neuronal function, we examined synaptic function and plasticity at the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses in hippocampal slices from Cdh1 heterozygous knockout mice and their wildtype littermates.

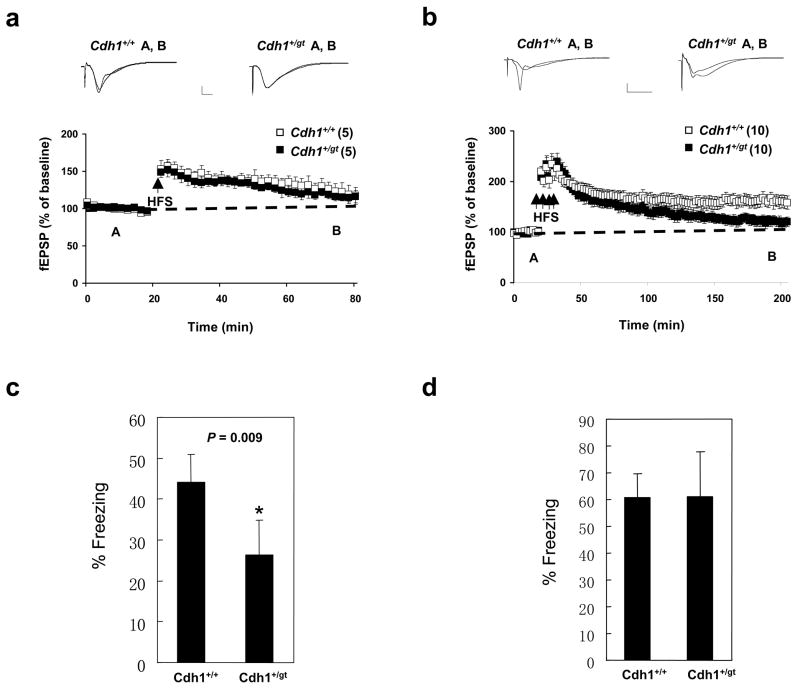

Basal synaptic transmission in area CA1 of hippocampal slices from the Cdh1+/gt mice was unaltered as indicated by similar synaptic input-output relationships between wildtype and Cdh1+/gt mice (Fig. S4c). Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF), a presynaptic form of short-term synaptic plasticity, was also comparable at multiple interpulse intervals between Cdh1 heterozygous knockout and wildtype mice (Fig. S4d). In hippocampal slices from Cdh1 heterozygous knockout mice, early-phase long-term potentiation (E-LTP) evoked by a single train of high-frequency stimulation (HFS, one 1-sec train at 100 Hz) resulted in potentiation of synaptic responses (116 ± 8% of baseline at 60 min after HFS) that was not significantly different from that in slices from wild-type littermates (117 ± 11% of baseline 60 min after HFS) (Fig. 5a). However, the late-phase LTP (L-LTP) evoked by multiple spaced trains of HFS (four 1-sec trains of HFS at 100 Hz with an intertrain interval of 5 min) was impaired in Cdh1 heterozygous knockout mice (Fig. 5b). In hippocampal slices from wild-type mice, robust L-LTP was induced that persisted for at least 3 hours (Fig. 5b). In contrast, L-LTP in slices from Cdh1 heterozygous knockout mice decayed back to baseline levels within 3 hours after the final train of HFS (p<0.001) (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that APC-Cdh1 may mediate the ubiquitination and degradation of proteins that have a negative effect on L-LTP, supporting the notion that both protein synthesis and degradation are required for the expression and maintenance of this long-lasting form of synaptic plasticity 18.

Figure 5.

Learning and memory defects in Cdh1 heterozygous mice. a. Early-phase LTP induced by a single 100 Hz stimulus (1s). 5 slices per mouse from a total of 5 mice of each genotype were used. Representative fEPSP recordings from time points A and B are shown for each condition. Calibration: 1 mV, 5 ms. b. Late-phase LTP elicited by four 100 Hz trains (1s) with 5 min intertrain interval. 10 slices per mouse from a total of 8 mice of each genotype were used. Representative fEPSP recordings from time points A and B are shown for each condition. Calibration: 1 mV, 5 ms. c. Analysis of contextual fear conditioning. d. Analysis of cued fear conditioning. 10 measurements were made in c and d and error bars indicate standard deviation.

Given the connection between synaptic plasticity and learning and memory, we wondered if Cdh1+/gt mice would display deficiencies in learning and memory. We therefore subjected Cdh1+/+ and Cdh1+/gt mice to behavior tests. We found that Cdh1+/gt mice performed poorly in contextual fear conditioning (Fig. 5c), a hippocampus-dependent process 19, 20. However, no difference was observed in cued (auditory) fear condition (Fig. 5d), which is less dependent on hippocampus 19, 20. These results indicate that Cdh1 haploinsufficiency results in hippocampus-dependent memory impairments and APC-Cdh1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of protein substrates plays an important role in learning and memory.

Herein, we have demonstrated that Cdh1 is required for the generation of placental giant cells. We identified Ets2 as a new substrate of APC-Cdh1. Ets2 is a proto-oncogene activated by Ras signaling 21, 22 and is believed to mediate Ras hyperactivation-induced senescence 15, 23. Thus, it is conceivable that APC-Cdh1 functions to limit Ets2’s oncogenic potential by constraining its levels. Finally, our electrophysiological and behavior results implicate APC-Cdh1 in hippocampus-dependent learning and memory.

METHODS

Methods

Generation and analysis of Cdh1 Knockout Mice

We obtained a Cdh1 gene-trap ES cell line (RRJ067) from BayGenomics. The cells were injected into blastocysts derived from C57BL/6 mice to produce chimeras. Subsequent breeding of the chimeras resulted in germline transmission of the trapped allele. Genotyping of the mice were done with a PCR-based protocol using the following primer pairs: for wildtype, 5′ actccgcactgctgaagaat 3′/5′ ccagtccaccaagttgaggt 3′ and for the mutant, 5′ cacaaggggctctttacg 3′/5′ ttggttttcgggacctgggac 3′.

Timed matings were used to obtain embryos at different developmental stages. The harvested embryos or placenta were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS and embedded in paraffin. 4μm thick sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Feulgen stain for visualizing DNA. The trapped LacZ activity was analyzed in E10.5 embryos with the method described previously 1, 24.

Cell Culture

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were isolated from E9.0–E9.5 embryos and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 2mM glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were first plated on 96-well plate and were designated as passage 0 (P0). They were transferred to 24-well plates (P1) and 6-well plates (P2). Experiments were performed with cells at P2 or higher. Proliferation of the MEFs was assessed with a cell proliferation kit (MTT) (Roche, IN) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

HeLa and 293T cells were culture in DMED supplemented with 10% FBS. To express Ets2 and Cdh1 transiently, the cells were transfected with the Ets2-expressing vector first. 24 hr later, the cells were split, replated, and transfected with the Cdh1-expressing vector or an empty vector.

To knockdown Ets2 expression, a retroviral Ets2 shRNA vector (V2MM_39638) was purchased from Open Biosystems and packaged into virions in 293T cells to transduce the shRNA into MEFs. The shRNA sequence is GGGATTTATGTAGCAGCTATT, targeting the 3′ UTR of mouse Ets2.

Western blot analysis and antibodies

E9.5 embryos or cultured cells were lysed in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4/1% NP-40/0.25% sodium deoxycholate/150 mM NaCl/l mM EDTA plus protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, IN)]. 50 μg total protein were separated in SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Cdh1 (clone DH01, Abcam); p27 (catalog # 2552, Cell Signaling Technology); Cdc20 (sc-8358, Santa Cruz Biotech.), cyclin B1 (sc-752, Santa Cruz Biotech.), Aurora B (catalog # 611083, BD Biosciences), Skp2 (sc-764, Santa Cruz Biotech.), p21(sc-397-G, Santa Cruz Biotech.), Plk1 (sc-17783, Santa Cruz Biotech.), and phospho H3 (catalog # 06-570, Millipore Corporation). Other antibodies used were anti-Flag (A8592, Sigma) and anti-myc (M5546, Sigma).

Electrophysiology

Transverse hippocampal slices (400 lm) were prepared from wildtype and Cdh1 heterozygous littermates (10–16 weeks of age). Slices were maintained at 30°C in an interface chamber perfused (1.5 ml/min) with oxygenated artificial CSF containing 125 mM NaCl/2.5 mM KCl/1.25 mM NaH2PO4/25 mM NaHCO3/25 mM D-glucose/2mM CaCl2/1 mM MgCl2. Extracellular field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were evoked by stimulation of the Schaeffer collateral pathway afferents and recorded in the CA1 stratum radiatum. Stable baseline synaptic transmission was established for 20 min with a stimulus intensity of 35–50% of the maximum fEPSP before LTP-inducing, high-frequency stimulation (HFS). Stimulus intensity of the HFS was matched to the intensity used in the baseline recordings. LTP was induced by either one train or four trains (5 min intertrain interval) of 100 Hz HFS for 1 s and measurements were shown as the average slope of the fEPSP from six individual traces collected over 2 min and standardized to baseline recordings. Cdh1 heterozygous and wildtype hippocampal slices were prepared simultaneously and placed in a chamber outfitted with dual-recording equipment, thereby minimizing day-to-day variations in slice preparation and recording. Two-way ANOVA and post-tests were used for electrophysiological data analysis with p < 0.05 as significance criteria.

Behavior testing

Fear conditioning was performed on 12 wild type and Cdh1 heterozygous mice according to the 2-day procedure developed by the Baylor Mouse Neurobehavior Core 25. Briefly, the mice were trained in the conditioning chamber. A sound, severed as the conditioning stimulus (CS), was given for 30 sec immediately following foot shock (0.7 mA, 2 sec). This pattern was repeated once after 2 min. 24 hours later, the mice were placed in the same environment and observed for 5 min without the sound stimulus, and their behavior was recorded (context test). The same batch of mice was tested 2 hrs later for freezing behavior in response to auditory CS in a completely different environment. Digital video recordings was analyzed with FreezeFrame software (Actmetrics, Evanstan, IL). Freezing was defined as the absence of visible movement, except for respiration. Data were analyzed with ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. H. Yu of UT Southwestern Medical Center for technical help and the transgenic core of BCM for microinjections. We thank E. Shin for excellent technical support. This work was supported in part by a NIH grant CA116097 to PZ and NIH grants NS034007 and NS047384 to EK.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L., E.R., and P.Z. planned the experiments. P.Z. conducted the scientific writing. M.L., Y.-H. S., and L.H. performed the experimental work and data analyses. X.H. and Z.W. provided technical help.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Li M, York JP, Zhang P. Loss of Cdc20 causes a securin-dependent metaphase arrest in two-cell mouse embryos. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:3481–3488. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02088-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stryke D, et al. BayGenomics: a resource of insertional mutations in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:278–281. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laronne A, et al. Synchronization of interphase events depends neither on mitosis nor on cdk1. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3730–3740. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorensen CS, et al. Nonperiodic activity of the human anaphase-promoting complex-Cdh1 ubiquitin ligase results in continuous DNA synthesis uncoupled from mitosis. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:7613–7623. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7613-7623.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edgar BA, Orr-Weaver TL. Endoreplication cell cycles: more for less. Cell. 2001;105:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart S, Fang G. Destruction box-dependent degradation of aurora B is mediated by the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome and Cdh1. Cancer research. 2005;65:8730–8735. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen HG, Chinnappan D, Urano T, Ravid K. Mechanism of Aurora-B degradation and its dependency on intact KEN and A-boxes: identification of an aneuploidy-promoting property. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:4977–4992. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4977-4992.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindon C, Pines J. Ordered proteolysis in anaphase inactivates Plk1 to contribute to proper mitotic exit in human cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2004;164:233–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang JN, Park I, Ellingson E, Littlepage LE, Pellman D. Activity of the APC(Cdh1) form of the anaphase-promoting complex persists until S phase and prevents the premature expression of Cdc20p. The Journal of cell biology. 2001;154:85–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei W, et al. Degradation of the SCF component Skp2 in cell-cycle phase G1 by the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature. 2004;428:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bashir T, Dorrello NV, Amador V, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. Control of the SCF(Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase by the APC/C(Cdh1) ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 2004;428:190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature02330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nature cell biology. 1999;1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsvetkov LM, Yeh KH, Lee SJ, Sun H, Zhang H. p27(Kip1) ubiquitination and degradation is regulated by the SCF(Skp2) complex through phosphorylated Thr187 in p27. Curr Biol. 1999;9:661–664. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bornstein G, et al. Role of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase in the degradation of p21Cip1 in S phase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:25752–25757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301774200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohtani N, et al. Opposing effects of Ets and Id proteins on p16INK4a expression during cellular senescence. Nature. 2001;409:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/35059131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lasorella A, et al. Degradation of Id2 by the anaphase-promoting complex couples cell cycle exit and axonal growth. Nature. 2006;442:471–474. doi: 10.1038/nature04895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gieffers C, Peters BH, Kramer ER, Dotti CG, Peters JM. Expression of the CDH1-associated form of the anaphase-promoting complex in postmitotic neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:11317–11322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fonseca R, Vabulas RM, Hartl FU, Bonhoeffer T, Nagerl UV. A balance of protein synthesis and proteasome-dependent degradation determines the maintenance of LTP. Neuron. 2006;52:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Modality-specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science (New York, NY) 1992;256:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behavioral neuroscience. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang BS, et al. Ras-mediated phosphorylation of a conserved threonine residue enhances the transactivation activities of c-Ets1 and c-Ets2. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:538–547. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy SA, et al. Rapid phosphorylation of Ets-2 accompanies mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and the induction of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor gene expression by oncogenic Raf-1. Molecular and cellular biology. 1997;17:2401–2412. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huot TJ, et al. Biallelic mutations in p16(INK4a) confer resistance to Ras- and Ets-induced senescence in human diploid fibroblasts. Molecular and cellular biology. 2002;22:8135–8143. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8135-8143.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia J, Lin M, Zhang L, York JP, Zhang P. The Notch Signaling Pathway Controls the Size of the Ocular Lens by Directly Suppressing p57Kip2 Expression. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:7236–7247. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00780-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paylor R, Tracy R, Wehner J, Rudy JW. DBA/2 and C57BL/6 mice differ in contextual fear but not auditory fear conditioning. Behavioral neuroscience. 1994;108:810–817. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.