1. Introduction

It is clear that there are reciprocal interactions between mammalian sleep and energy homeostasis. Sleep disruption results in increased demand for energy which in turn motivates subjects to consume more food in an to attempt to redress the imbalance [23,30]. This suggests that sleep disruption in rats will increase motivation to perform food rewarded tasks due to the additive effects of food restriction and sleep disruption on hunger. Thus, food rewarded tasks performed during or after sleep disruption may underestimate the effect of sleep disruption on performance (for example, in tests of attention sleep disruption would be predicted to impair performance, whereas increased hunger would be predicted to enhance motivation and performance). An alternative way to motivate rats to perform behavioral tasks is to use water restriction and water reward. Water is not a direct/central component of energy metabolism/homeostasis, and, as such, may not be affected by sleep disruption.

Although recent studies investigating the effect of sleep disruption on attention in rats have relied on thirst to motivate performance [3,4], little is known about the effect of sleep disruption on thirst and operant performance motivated by thirst. Experiment 1 systematically investigated the effect of both total sleep deprivation (SD) and experimental sleep fragmentation (SF) on thirst, and on motivation to perform an operant task for water reinforcement in 22 month old Fischer-Norway rats. The amount of water consumed by rats during a 15 min period of freely available water immediately after a 24h period of sleep disruption was measured, or, in a separate experimental phase, during the entire 24h sleep disruption period (SD or SF). Thereafter, the effect of 5 days of sleep disruption on motivation for water reward was assessed using the progressive ratio task (widely considered to be a straightforward index of motivation [10]).

Although much of our published work has used mature Fischer-Norway rats with both SD and SF [3,26,27], we and others also use young(er) Sprague-Dawley rats in similar studies. Hence, experiment 2 was designed to confirm that SD does not alter thirst or motivation for water reward in 6-month old Sprague-Dawley rats. Furthermore, a group of 22 month old Sprague-Dawley rats was included in the 24h SD phase of experiment 2 in order to allow a direct comparison with the age matched Fischer-Norway rats used in experiment 1. Additional measures such as daily food consumption and daily body weight were also added in experiment 2, in order to confirm previously published findings describing increased food consumption and decreased body weight with prolonged sleep disruption [14,23].

We hypothesized that, as water is not a central component of energy metabolism, sleep disruption would have no effect on water consumption or motivation for water reward. In contrast, consistent with the literature, we predicted an increase in food consumption and a decrease in body weight across the 5 days of SD in experiment 2. Such findings would indicate that although sleep disruption alters energy metabolism it does not alter thirst or motivation for water reward, suggesting that water restriction is well suited for experiments examining the effect of sleep disruption on reward motivated behavioral tests in rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Experiment 1 used 22 month old male Fischer-Norway rats (N=8; Charles River Breeding Laboratories) weighing between 400 – 450 grams at the start of the study. Experiment 2 used male Sprague-Dawley (Charles River Breeding Laboratories) rats that were 6 months (N=8), or 22 months (N=7) old, at the start of the study (2 different groups of rats weighing ~500g and ~700g respectively). All rats were housed under constant temperature (23±1°) and a 12:12 light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h) with food available ad libitum. All animals were treated in accordance with Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care’s policy on care and use of laboratory animals. All experiments conformed to U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Harvard University, and U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines on the ethical use of animals.

2.2. Water restriction procedure

In order to motivate the rats to perform the operant task for water reward they were water restricted for ~23 h prior to the daily operant testing sessions, during all experimental conditions. Rats earned up to 3 ml of water in each daily operant session (100µl/reward), and, afterwards, received 15 min of ad lib access to water to insure adequate daily hydration (20 to 30 min of ad lib water access was provided on days the rats were not tested). In experiment 1, rats were weighed weekly to ensure that their body weight did not drop below 90% of their baseline “free water” body weight. In experiment 2, rats were weighed daily for the same purpose, and to allow body weight to be used as a dependent measure. Rats on this water restriction procedure remained active and appear healthy and do not exhibit clinical signs of dehydration; for example all rats maintained or gained body weight when not experiencing prolonged sleep disruption (see [3, 4]).

2.3. Sleep deprivation (SD), sleep fragmentation (SF) and the movement control (MC) procedures

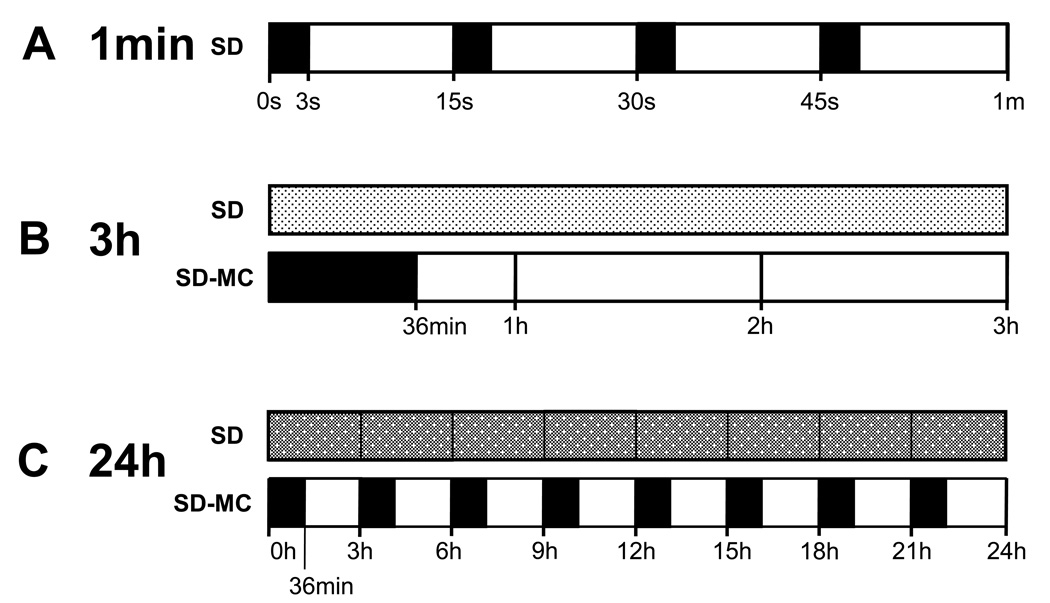

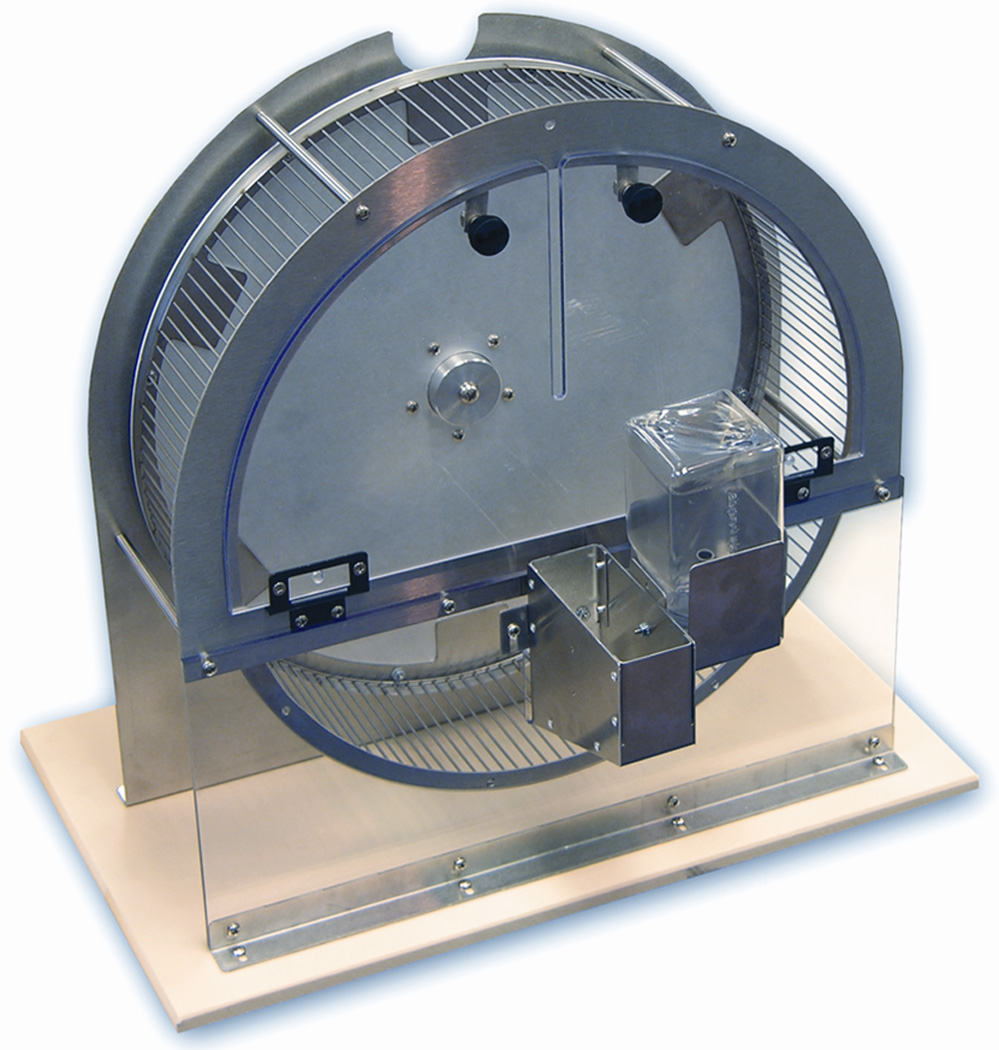

Rats remained singly housed throughout the SD and SF experiments, residing in custom modified activity wheels (Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN; Fig. 1).) that were controlled by Lafayette’s ‘Activity Wheel Monitor’ software. These motorized, stainless steel activity wheels have a 35.5 cm diameter, and internal wheel width of 10.9 cm. Rats were habituated to the activity wheel environment, including 1 h of activity wheel motion (5 min on: 5 min off) at 1100 h for 2 days before the experiments began. Twenty-four h of SD (1100 h - 1100 h) was produced by the rotational movement of the activity wheel, programmed on a schedule of 3 s on and 12 s off, at a speed of 3m/min (see Fig. 2). Actual measurements indicated that the duration of wheel movement ranged from 3 s to 5 s, and the wheel was motionless for 11–14 s. Similar parameters have been previously shown to produce greater than 91% wakefulness during a 24h period of SD [3,12,13,18,27]. Twenty-four h of SF (1100 h -1100 h) was produced by the rotational movement of the activity wheel with a program schedule of 4s on and 56s off, at a speed of 3m/min. To control for the non-specific effects of the activity wheel (e.g., cage movement/locomotor activity) wheel movement control conditions (MC) were used for both the SD (SD-MC; see Fig 2) and SF (SF-MC) conditions.

Fig. 1.

Photograph of an activity wheel. (Reproduced with permission of Lafayette Instrument Co.; Lafayette, IN).

Fig. 2.

Schematic of wheel movement during the sleep deprivation (SD) protocol shown in the following time scales: A: 1 min, B: 3h, and C: 24h of the SD and the SD movement control (SD-MC) protocols. Dark bars or shading indicate when the wheel is moving, and open bars when the wheel is stationary. The scale in B and C precludes a detailed representation of the frequency of the on/off periods in the SD bars (which remains 3 sec. on / 12 sec. off). The pattern of movement for the SD-MC protocol repeats every 3h. The SD-MC protocol is not shown for the 1 min duration because it would simply be a solid black bar. h = hour, min = minute, s = second.

In the SD movement control condition (SD-MC) the wheel revolved at 3m/min for 36 min in every 3h period. In the SF movement control (SF-MC) condition the wheel revolved at 3m/min for 12 min in every 3h period. This ensured that rats experienced the same amount of wheel movement in the SD, SF and corresponding MC conditions, but the MC conditions provided ample opportunity to enter and maintain deep sleep. There was also a fifth ‘baseline’ experimental condition in which the rats remained in the activity wheels without any wheel movement (activity wheel control: AWC). Twenty-four hours of experimental SD or SF sessions were always separated by at least 3 full days to allow the rats to recover. Rats performed the progressive ratio task at the usual time on non-experimental weekdays. To confirm that longer periods of SD or SF did not alter performance in the progressive ratio task, the breakpoint was also measured during 5 continuous days of SD, SF, or one of the MC conditions (using the activity wheel parameters described above for the 24h/day conditions).

2.3. Progressive ratio task

Rats were trained and then run daily at 1100 h on weekdays in the progressive ratio task. The progressive ratio task was initially developed as a measure of reinforcement strength [15, 16], but is now widely considered to be a straightforward index of motivation [10]. Progressive ratio behavior in rats has been extensively studied [34] and is sensitive to psychopharmacological manipulations [8,11, 33], body weight manipulations [9], and rat strain [10]. The progressive ratio task used herein was modeled on a published version in which the number of operant responses (‘nose pokes’ hereafter) were increased by 1 response to earn the next water reward [10,11]. Thus the first reward is earned after a single nose poke, whereas the 2nd reward requires 2 new nose pokes, the 3rd 3 new nose pokes, etc. The primary measure of performance in the task is the ‘breakpoint’, defined as the number of nose pokes made in order to receive the last reward (i.e., the point at which the rats stopped responding, which indicates they are no longer motivated to perform for the next reward). Progressive ratio sessions lasted 15 min, a duration which is sufficiently long enough for the rats to cease responding prior to the end of the session [10,11]. There was no upper limit set on the number of permissible responses or rewards.

The older rats in both experiments were well habituated to the testing procedures having previously experienced 24h SD and SF, at least 6 weeks prior to the start of progressive ratio training in unrelated experiments [3]. The younger Sprague-Dawley rats in experiment 2 were first habituated to the operant chambers over several days, before undergoing stimulus-response training and then specific progressive ratio task training. After habituation and initial training all rats performed baseline progressive ratio sessions until performance stabilized (< 10 sessions for all ages and strains).

2.4. Experiment 1: water consumption and motivation for water reward in 22 month old Fischer-Norway rats

In the first phase of the experiment the rats were restricted to 15 min of free water availability at the end of the 24h SD, SF, AWC, or MC periods and the amount of water consumed during this 15 min period was measured. In the second (separate) phase of the experiment rats were able to consume water throughout the 24h period of SD, SF, AWC, SD-MC, or SF-MC conditions. In both phases the amount of water consumed during the period of water availability was measured. Motivation for water reward was assessed by measuring breakpoint performance in the progressive ratio task during both the 24h exposure conditions, and also during 5 continuous days of the SD, SF, AWC, SD-MC, or SF-MC.

2.5. Experiment 2: water consumption, motivation for water reward, food consumption, and body weight in 6 month and 22 month old Sprague-Dawley rats

For both 6 and 22 month old Sprague-Dawley rats water consumption and motivation for water reward after 24h SD occurred in the same manner as in experiment 1, except there was no SF condition (and thus no SF-MC) in experiment 2. Only the 6-month old Sprague-Dawley rats were tested in the experiment using 5 days of continuous exposure to SD, AWC, or SD-MC conditions. Daily measures obtained during the 24h or the 5 day exposure to the SD, AWC or SD-MC conditions included the following: the amount of water consumed during each day during the 15 min period of free water availability, the progressive ratio breakpoints, the amount of food consumed during each 24h period, and body weight measured immediately after the period of 15 min of water availability.

2.6. Experimental design and data analysis

In both experiments 1 and 2 the exposure to the experimental conditions was initially randomized at the start of each experiment, and, thereafter, presented using a within subjects counterbalanced, crossover design. With this design the normative/baseline data are provided by the AWC control condition.

The 15min and 24h water consumption data were analyzed using one way ANOVAs. Post hoc comparisons were performed with dependent means t-tests. All measures during the 5 days of SD, SF, and control conditions were analyzed via 2-factor ANOVA (day and condition), with repeated measures on both factors (i.e., a totally within subject design was used). ANOVA post hoc analyses were performed by Tukey HSD tests for equal N. The 5 day water and food consumption data was transformed into the difference scores between days to produce 5 data points per rat (i.e. each data point was the difference between performance on a day, and performance from the immediately preceding day). Note that due to an inability to weigh the food immediately before the start of experiment 2, food weight data from the 24h-only condition were used for the day 1 data of the 5 day exposure condition (i.e., the day 1 food consumption data plotted in Fig. 6 are the same data that are plotted in Fig. 5; this combination of the food consumption data from the 24h exposure conditions with the 5 day exposure conditions is justified because these were the same rats, and their experience in the first 24h of exposure was identical in both the 24h and the 5 day phases of experiment 2). Although α was set at 5% all p values were adjusted via the modified (ranked) Bonferroni method to account for α level inflation.

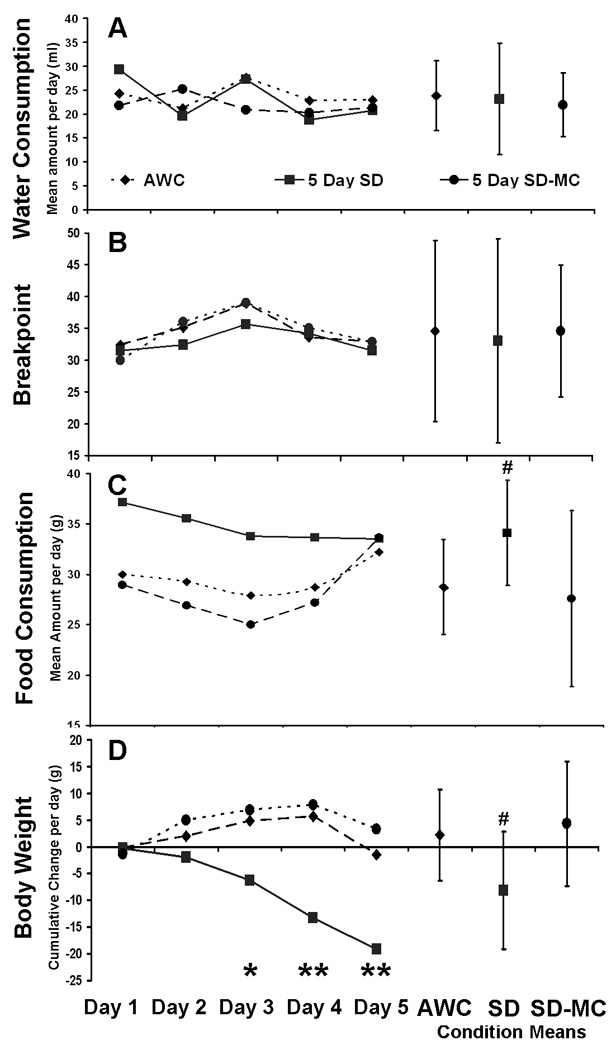

Fig. 6.

The daily (left side) and 5 day mean (right side) effect of 5 days of SD or the control conditions (SD-MC and AWC) on water consumption, progressive ratio performance, food consumption, and body weight, in 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats. Five days of SD produced no change in water consumption (A) and motivation for water reward (B), but did increase food consumption as early as day 1 (C) and decreased body weight (D). The day 1 food consumption data are the same as those plotted in Fig. 5 (see text for details). The left side of each panel shows the data for each of the 5 continuous days of SD and control conditions. The right side of each panel shows the means collapsed across days for each corresponding measure. * = a significant difference at p<0.05 between the SD and SD-MC conditions for a change in body weight on that day, and ** = a significant difference at p<0.001 between the SD condition and the control conditions for a change in body weight for those days. # = a significant difference at p<0.05 between the mean of the SD condition and both control conditions for both food consumption and body weight. Errors bars are ± 1 standard deviation. N=8.

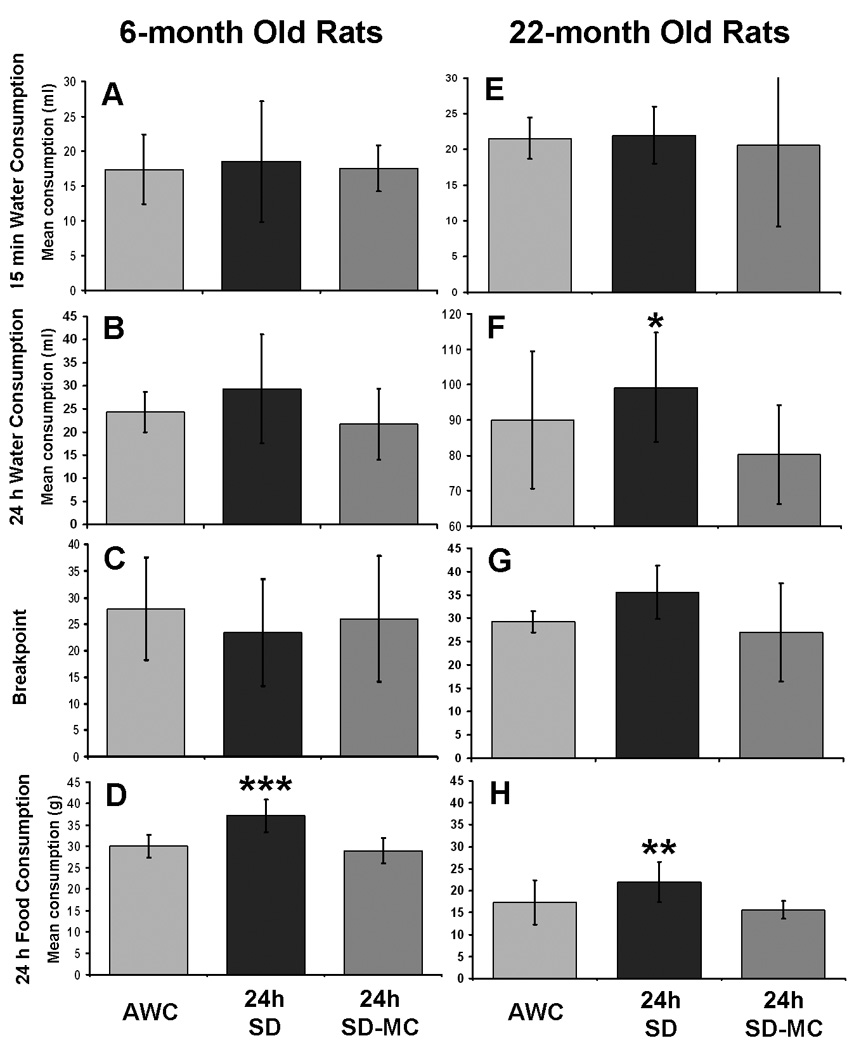

Fig. 5.

The effect of 24h SD on 6 month (N=8), and 22 month (N=7), old Sprague-Dawley rats in experiment 2. A & E: 24h of SD did not alter water consumption during a 15 min period of water availability immediately following 24h exposure to SD in either age group. B & F: 24h of SD does not alter water consumption throughout the 24h period of exposure to SD in the 6 month old rats, but increases water consumption in the 22 month old rats relative to the movement control condition (SD-MC). C & G: 24h of SD does not alter motivation for water reward in either age group, as indicated by comparisons of the progressive ratio task breakpoint data of the SD condition with the control conditions. D & H: total 24h food consumption increased during exposure to 24h SD in both age groups relative to both control conditions. * = a significant difference at p<0.05 between SD and the (SD-MC) condition. ** = a significant difference at p<0.01 between SD and both control conditions. *** = a significant difference at p<0.001 between SD and both control conditions. Errors bars are ± 1 standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1 Experiment 1: water consumption and motivation in 22 month old Fischer-Norway rats

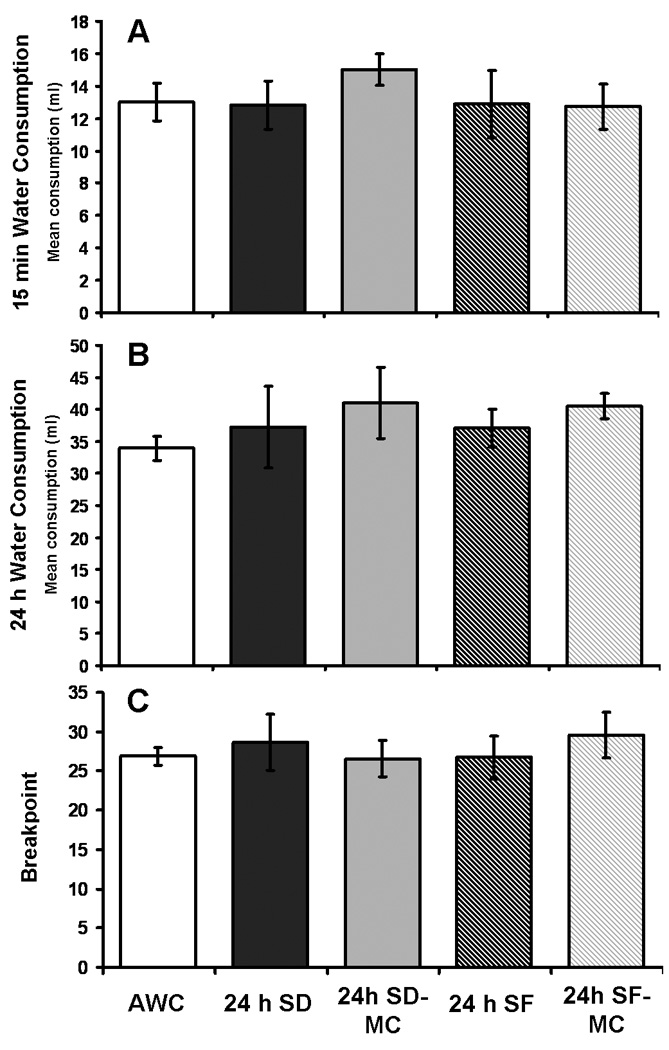

Compared to control conditions, 24h of SD or SF had no effect on the amount of water consumed by water restricted 22 month old Fischer-Norway rats during a 15 min period of ad lib access to water that immediately followed the 24h of experimental exposure (see Fig. 3A), or on the amount of water consumed throughout the 24h period of experimental exposure (i.e., with water freely available during the entire 24h; all p’s>0.6, see Fig. 3B). Using weekly measures, the body weights of the Fischer-Norway rats did not change significantly during the course of the experiments.

Fig. 3.

Water consumption and progressive ratio task performance in 22 month old Fischer-Norway rats was not altered by any of the experimental conditions (SD, SF, AWC, SD-MC, or SF-MC) in experiment 1. A: water consumption during a 15 min period of water availability immediately following 24h exposure to SD, SF, or the control conditions. B: water consumption throughout the 24h period of exposure to SD, SF, or the control conditions. C: progressive ratio task performance (mean breakpoint) immediately after exposure to 24h SD, SF, or the control conditions. A breakpoint of 25 to 30 indicates that the rats stopped responding after drinking 2.5 to 3.0 ml of water. Errors bars in all figures are ± 1 standard deviation. N=8.

3.2. Experiment 1: motivation for water reward in 22 month old Fischer-Norway rats

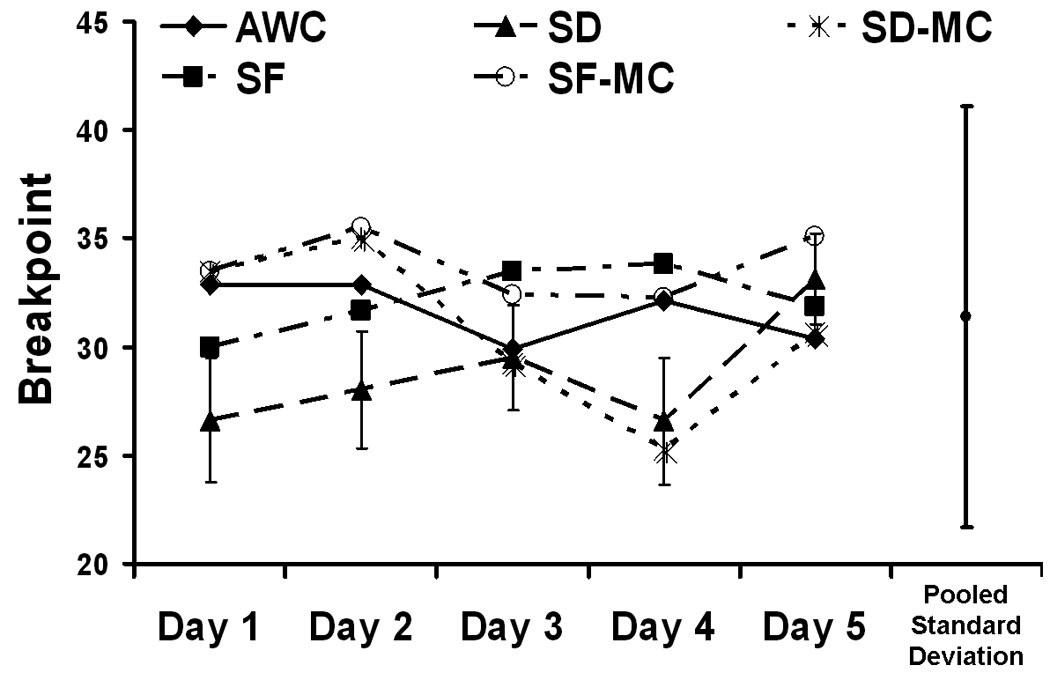

As shown in Fig. 3C, progressive ratio task performance was not affected by 24h of SD, SF, AWC, or either of the MC conditions. Similarly, Fig. 4 shows that there was no effect of 5 days of SD, SF, AWC, or either MC condition on progressive ratio performance (p>0.8), nor was there any effect across time (p>0.2). The interaction effect approached significance (p=0.071). Post hoc analysis revealed that this was primarily due to the (non-significant) drop in performance in the SD and SD-MC conditions on day four relative to the SF condition, a drop that was well within the pooled standard deviation (see Fig. 4). Furthermore, post hoc one way ANOVAs’ for each condition in isolation analyzing performance across the 5 days revealed no significant effect (all p’s>0.2) for any condition.

Fig. 4.

Progressive ratio task performance was not altered by 5 days of SD, SF, or the control conditions in the Fischer-Norway rats of experiment 1, indicating that sleep disruption does not alter motivation for water reward. Errors bars are ± 1 standard deviation. N=8.

3.3. Experiment 2: the effect of 24 h of SD on water consumption, motivation for water reward, food consumption, and body weight in 6 month and 22 month old Sprague-Dawley rats

Twenty-four h of SD had no effect on the amount of water consumed by 6 month or 22 month old water restricted Sprague-Dawley rats during a 15 min period of access to water that immediately followed the end of the 24h SD period (without water available), when compared to the two control conditions (AWC and SD-MC; p’s > 0.85, See Fig. 5A and 5E respectively). In separate sessions, 24h of SD had no effect on the amount of water consumed throughout the 24h SD period when compared to the control conditions in 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats (p>0.88, see Fig. 5B). However, the same analysis in 22 month old rats revealed a significant main effect of condition (F(1,10)=6.3, p<0.025, see Fig. 5F). Post hoc analysis of this result revealed a significant difference between the SD and SD-MC conditions for the 22 month old rats (p<0.025; i.e., rats in the SD condition drank more), but no difference between the AWC and SD conditions (p>0.9). Breakpoints in the progressive ratio task were not different between any of the conditions after 24h of SD, AWC, or SD-MC in the 6 month age group of rats (p > 0.73, see Fig. 5C), but approached significance in the 22 month old rats (p=0.067, see Fig. 5G). The increase in food consumption over 24h was significant in both the 6 month and 22 month old Sprague-Dawley rats (6 month; F(1,14)=16.8, p<0.001), 22 month; (F(1,10)=5.8, p<0.025), see Fig. 5D and 5H respectively). Post hoc analysis revealed a significant difference between the SD condition and both control conditions for both age groups (SD × SD-MC; 6 month p<0.001, 22 month p<0.001, and SD × AWC; 6 month p<0.01, 22 month p<0.01; i.e., all rats in the SD condition ate significantly more than both control conditions). Body weights did not change in either the 6 month or 22 month old rats across the 24h (all p’s >0.36), data not shown.

3.4. Experiment 2: the effect of 5 days of SD on water consumption, motivation for water reward, food consumption, and body weight in 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats

Five days of continuous SD had no effect on water consumption compared to either control condition in the 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats (p>0.3, see Fig. 6A), nor was there a simple main effect of day (p>0.3). While the interaction effect approached significance (p=0.08), this analysis wasn’t central to the hypotheses being tested, and thus wasn’t examined further.

There was also no significant effect of the 5 days of experimental exposure on breakpoint in the progressive ratio task for the six month old Sprague-Dawley rats. (p>0.8; Fig. 6B), nor was there an interaction effect (p>0.9). However, the main effect of days was significant for the breakpoint analysis (p(5,56)=3.81, p<0.025). To explore this finding the data were collapsed across all experimental conditions and a post hoc analysis revealed that progressive ratio performance improved slightly on day three when compared to days 1 and 5 (p’s<0.05). Again this analysis wasn’t central to the hypotheses, and, hence, was not examined further.

As predicted, the food consumption of 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats experiencing 5 days of continuous SD increased compared to control conditions. This difference appeared as early as the first day of SD (based on data from the 24h exposure conditions as described above), and the rats in the SD condition maintained this high level of food consumption throughout the entire 5 day period of SD (see Fig. 6C). In contrast, rats in control conditions consumed normal amounts of food until day 5, at which point their consumptions rose to levels equal to that when exposed to continuous SD. The reason for the increase in food consumption by the two control groups on the last day of the 5 day experiment is not known. Analysis of these results reveal a significant main effect of experimental condition (F(2,42)= 8.7, p<0.01), but no effect of days, and no interaction effect (both p’s >0.15). When food consumption was collapsed across the 5 days there was a clear and significant difference between experimental conditions (see the right side of Fig. 6C which illustrates the 5 day mean quantity of food consumed, ± std deviation; F(2,21)=5.09, p<0.025). Post hoc analysis revealed that rats ate significantly more food during the SD condition than in either of the control conditions (SD × AWC; t(7)=2.74, p<0.025, and SD × SD-MC; t(7)=3.7, p<0.01).

Although the body weights of the 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats were very similar at the start of experimental phase, rats that experienced 5 days of continuous SD lost significant amounts of body weight on days 3, 4, and 5 (see Fig. 6D), unlike rats in the control conditions who typically gained small amounts of weight across the 5 days. Analysis revealed a simple main effect of experimental condition (F(2,56)=4.58, p<0.05). Similarly both the main effect of day, and the interaction effect, were significant (day F(4,56)=9.1, p<0.001, interaction F(8,56)=4.7, p<0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that day three of the SD condition differed significantly from the SD-MC condition of the same day, and that days 4 and 5 in the SD condition differed significantly from days 4 and 5 of both the AWC and SD-MC conditions (all p’s >0.05, see left side of Fig. 6D). Six month old Sprague-Dawley rats in the SD condition lost an average of 8.2g/day across the 5 days of SD, while rats in the AWC and SD-MC conditions gained 2.2 and 4.3g across the same period, respectively. These differences were significant and are illustrated on the right side of Fig. 6D (24h SD × AWC t(7)=2.98, p<0.025, 24h SD × 24h SD-MC t(7)=2.79, p<0.025). Note that at the end of the 5 day SD period (i.e., on day 5) rats had, on average, lost a total of 20g. However, this is only a loss of 3.6% of pre-experimental body weight on average, and was quickly recovered when the SD protocol was stopped.

4. Discussion

Neither water consumption nor motivation for water reward was altered by exposure to total sleep deprivation (SD) or sleep fragmentation (SF) in rats. The amount of water consumed under both free water (24h consumption) and water restricted (using a 15 min water consumption test) conditions did not change as a function of exposure to SD or SF. Similarly, performance in the progressive ratio task, which provides a direct measure of motivation for a water reward, was not affected by up to 5 days of SD or SF. These findings were consistent across two rat strains (Fischer-Norway and Sprague-Dawley) and two age ranges (6 month and 22 month old Sprague Dawley rats). In contrast, body weights dropped steadily during the 5 days of SD (e.g., on average by ~4g/day for the 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats), and food consumption increased during the first day of SD, and remained elevated throughout the 5 days of continuous SD (e.g., average daily food consumption increased by 27% for the 6 month old Sprague-Dawley rats compared to control conditions). The combined results indicate that it is unlikely that alterations in motivation underlie any effects of sleep disruption on performance measures previously described in water rewarded rats [3,4].

The results reported herein are consistent with an earlier finding in humans that reported no increase in subjective or objective ratings of thirst in subjects that had just experienced either 1 night of REM, or 1 night of NREM sleep deprivation [24]. The only record of the effect of sleep disruption on water consumption in rats that we are aware of is reported in Rechstaffen et al. [31] who found that rats chronically sleep deprived for up to 33 days drank significantly less during sleep disruption when compared to their baseline water consumption. However, this result is confounded by the fact that a similar decrease in water consumption was evident in control rats, suggesting that methodological procedures may have been the cause of the decreased water consumption, rather than being caused by the sleep disruption itself [31] although the literature on the effect of sleep disruption on thirst and water motivation is admittedly sparse.

In contrast to the limited research investigating the interaction between sleep loss and thirst, a number of human and animal studies have studied the interaction between sleep loss and hunger, and there is converging evidence that the hyperphagia commonly produced by sleep disruption is due to the increase in energy metabolism produced by sleep disruption. In a study comparing 10h and 4h of time-in-bed, Knutson et al. [20] note that human levels of leptin fell and levels of ghrelin rose (hormonal changes that are associated with an increase in subjective hunger) in the sleep restriction group when compared to the well rested control group. The authors suggest that “sleep loss may alter the ability of leptin and ghrelin to accurately signal caloric need” (by incorrectly producing an internal perception of insufficient energy availability). This is both plausible and consistent with the available evidence. Similarly Penev [30] suggests that subjects eat more during sleep disruption due to a perceived increase in energy needs, whereas, in reality, energy needs do not change that much, and may even decrease. Thus, Penev states that “sleep deprived humans may defend their energy homeostasis more vigorously” than is actually required. In summary, recent work suggests that sleep disruption can lead to changes in diet and energy metabolism that may contribute to an increased appetite, risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome and diabetes (for review see, [17,19,28,29,35]. There is also wide agreement in the literature that sleep deprived rats’ increase their intake of food while nonetheless losing weight [6, 20,21,22,31,32] and this pattern of results was also found in experiment 2 of the current study. Despite this consensus, several recent studies using either REM sleep deprivation, or total sleep deprivation, in rats find less pronounced increases in food consumption and decreases in body weight, particularly during the first 5 days of sleep disruption [14,23,25].

We have previously shown that rats rewarded with water performing a sustained attention task suffer a clear impairment in their performance after either sleep deprivation [3], or immediately after local microdialysis administration of 300µM adenosine directly into the basal forebrain [4]. This later finding is consistent with the literature indicating that adenosine is an inhibitory neuromodulator and putative sleep factor that inhibits wakefulness promoting neurons of the basal forebrain and thereby leading to a decrease in cortical arousal and a subsequent increase in drowsiness/sleep (for review see [2,36]). In our published studies that described impairments of attention in response to manipulations hypothesized to increase sleepiness we reported that the number of overall responses (a crude measure of motivation) did not change as a result of 24h sleep deprivation [3] or adenosine manipulation [4]. The present findings indicate that the changes in attention we observed were very unlikely to have been influenced by sleep disruption induced changes in motivation for water reward. Therefore, we can be confident that the behavioral deficits reported in our earlier papers are not confounded by sleep disruption influencing the motivation for water reward. In contrast, studies using food restriction and food reward to motivate rodents in behavioral tasks need to consider that the interaction between hunger and sleep disruption is likely to increase motivation to perform food rewarded behavioral tasks (for example see, [1,5,14,26]). Fortunately, an increase in food motivation is generally predicted to improve behavioral performance in food reward motivated tasks, whereas sleep disruption is typically predicted to do the opposite on the same tasks (i.e., impair performance), thus mitigating concern about potential confounds in published studies that have combined sleep disruption with food motivated behavioral tests in rodents.

In conclusion, the rats exposed to total sleep deprivation or sleep fragmentation for up to 5 days showed no change in the consumption of water or in their motivation for water reward, but they did increase food consumption and lost body weight. The fact that sleep disruption does not alter water consumption or motivation, but does alter food consumption and subjective hunger, argues strongly for the use of water rewarded tasks in experiments examining the effect of sleep disruption on behavioral tests such as operant tests of attention, learning, or memory.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lauren Kane, Kathryn Dugger, Sabrina Taylor, Jessin Varghese, Melissa Chace, Elizabeth Davis, Courtney Earle, Brittany Roy, Timothy Connors, Molly Little, and Nina Connolly for technical assistance, and John Franco for care of the animals. We thank Lauren Shifflett and James McKenna for careful proofreading of the manuscript. This research was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service Award to RES, P50 HL060292 (RES & RWM), R01 MH039683 (RWM), T32 HL07901 (MAC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT: This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: MAC designed the research, conducted the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the paper, RES and RWM designed research, evaluated data, and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarenga TA, Andersen ML, Velázquez-Moctezuma J, Tufik S. Food restriction or sleep deprivation: which exerts a greater influence on the sexual behaviour of male rats? Beav Brain Res. 2009 Sep 14;202(2):266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basheer R, Strecker RE, Thakkar MM, McCarley RW. Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2004 Aug;73(6):379–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christie MA, McKenna JT, Connolly NP, McCarley RW, Strecker RE. 24 hours of sleep deprivation in the rat increases sleepiness and decreases vigilance: introduction of the rat-psychomotor vigilance task. J Sleep Res. 2008a;17(4):376–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christie MA, Bolortuya Y, Chen LC, McKenna JT, McCarley RW, Strecker RE. Microdialysis elevation of adenosine in the basal forebrain produces vigilance impairments in the rat psychomotor vigilance task. Sleep. 2008b;31(10):1393–1398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Córdova CA, Said BO, McCarley RW, Baxter MG, Chiba AA, Strecker RE. Sleep deprivation in rats produces attentional impairments on a 5-choice serial reaction time task. Sleep. 2006 Jan 1;29(1):69–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everson CA, Bergmann BM, Rechtschaffen A. Sleep deprivation in the rat: III. Total sleep deprivation. Sleep. 1989;12(1):13–21. doi: 10.1093/sleep/12.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everson CA, Crowley WR. Reductions in circulating anabolic hormones induced by sustained sleep deprivation in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286(6):E1060–E1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00553.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson SA, Paule MG. Acute effects of pentobarbital in a monkey operant behavioral test battery. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;45(1):107–116. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson SA, Paule MG. Progressive ratio performance varies with body weight in rats. Behavioural Processes. 1997;40:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(97)00786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson SA, Paule MG, Cada A, Fogle CM, Gray EP, Berry KJ. Baseline behavior, but not sensitivity to stimulant drugs, differs among Spontaneously Hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto, and Sprague-Dawley rat starins. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2007;29:547–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson SA, Holson RR, Paule MG. Effects of methylazoxymethanol-induced micrencephaly on temporal response differentiation and progressive ratio responding in rats. Behavioral and Neural Biology. 1994;62(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong H, McGinty D, Guzman-Marin R, Chew KT, Stewart D, Szymusiak R. Activation of c-fos in GABAergic neurons in the preoptic area during sleep and in response to sleep deprivation. J Physiol. 2004;556:935–946. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.056622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzmán-Marín R, Suntsova N, Stewart DR, Gong H, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Sleep deprivation reduces proliferation of cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in rats. J Physiol. 2003;549:563–571. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanlon EC, Andrzejewski ME, Harder BK, Kelley AE, Benca RM. The effect of REM sleep deprivation on motivation for food reward. Beh Brain Res. 2005;163:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134:943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodos W, Kalman G. Effects of increment size and reinforcer volume on progressive ratio performance. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 1963;6:387–392. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horne J. Short sleep is a questionable risk factor for obesity and related disorders: statistical versus clinical significance. Biol Psychol. 2008 Mar;77(3):266–276. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y, Mckenna JT, Bolotuya Y, McCarley RW, Strecker RE. Assessment of behavioral sleepiness during chronic sleep restriction in rats. Society for Neuroscience. 2007;632.5 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knutson KL, Van Cauter E. Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:287–304. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.033. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E. The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep Med Rev. 2007 Jun;11(3):163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koban M, Swinson KL. Chronic REM-sleep deprivation of rats elevates metabolic rate and increases UCP1 gene expression in brown adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Jul;289(1):E68–E74. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00543.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koban M, Stewart CV. Effects of age on recovery of body weight following REM sleep deprivation of rats. Physiol Behav. 2006 Jan 30;87(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koban M, Sita LV, Le WW, Hoffman GE. Sleep deprivation of rats: the hyperphagic response is real. Sleep. 2008 Jul 1;31(7):927–933. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koulack D, De Koninck J, Oczkowski G. Percept Mot Skills. Field dependence and the effect of REM deprivation on thirst. 1978 Apr;46(2):559–562. doi: 10.2466/pms.1978.46.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins PJ, D'Almeida V, Nobrega JN, Tufik S. A reassessment of the hyperphagia/weight-loss paradox during sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2006 Sep 1;29(9):1233–1238. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCoy JG, Tartar JL, Bebis AC, Ward CP, McKenna JT, Baxter MG, McGaughy J, McCarley RW, Strecker RE. Experimental sleep fragmentation impairs attentional set-shifting in rats. Sleep. 2007 Jan;30(1):52–60. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKenna JT, Cordeira JW, Christie MA, Tartar JL, McCoy JG, Lee E, McCarley RW, Strecker RE. Assessing sleepiness in the rat: a multiple sleep latencies test compared to polysomnographic measures of sleepiness. J Sleep Res. 2008 Dec;17(4):365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nedeltcheva AV, Kilkus JM, Imperial J, Kasza K, Schoeller DA, Penev PD. Sleep curtailment is accompanied by increased intake of calories from snacks. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;89(1):126–133. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26574. Epub 2008 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nisoli E, Carruba MO. Emerging aspects of pharmacotherapy for obesity and metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Res. 2004 Nov;50(5):453–469. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penev PD. Sleep deprivation and energy metabolism: to sleep, perchance to eat? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2007 Oct;14(5):374–381. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282be9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rechtschaffen A, Gilliland MA, Bergmann BM, Winter JB. Physiological correlates of prolonged sleep deprivation in rats. Science. 1983 Jul 8;221(4606):182–184. doi: 10.1126/science.6857280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rechtschaffen A, Bergmann BM. Sleep deprivation in the rat: an update of the 1989 paper. Sleep. 2002 Feb 1;25(1):18–24. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts DC, Bennett SA, Vickers GJ. The estrous cycle affects cocaine self-administration on a progressive ratio schedule in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;98(3):408–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00451696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skjoldager P, Winger G, Woods JH. Effects of GBR 12909 and cocaine on cocaine-maintained behavior in rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1993 Jun;33(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(93)90031-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Effects of poor and short sleep on glucose metabolism and obesity risk. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009 May;5(5):253–261. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strecker RE, Morairty S, Thakkar MM, et al. Adenosinergic modulation of basal forebrain and preoptic/anterior hypothalamic neuronal activity in the control of behavioral state. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115:183–204. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00258-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]