Abstract

This study examined the relationship between Cherokee self-reliance and related values expressed through word-use in stories of stress written by Cherokee adolescents. The overall aim of this pilot study was to test the feasibility of using cultural appropriate measurements for a larger intervention study of substance abuse prevention in Cherokee adolescents. A sample of 50 Cherokee adolescent senior high school students completed the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire and wrote their story of stress. The Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) program, a word-based computerized text analysis software, was used to report the percentage of words used in the selected word categories in relation to all the words used by a participant. Word-use from the stories of stress were found to correlate with Cherokee self-reliance.

Keywords: Cherokee Self-Reliance, Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, Culture, Stress

Introduction

The stress created by poverty, social disenfranchisement, and social change is part of everyday life for many Native American youth. Compared with other ethnic groups, few Native American adolescents graduate from high school, fewer still will complete college, and nearly twice as many will live in poverty (Spicer, 2001). The health status of Native American adolescents is below that of the general adolescent population with striking differences in areas such as depression, suicide, anxiety, substance abuse, general health status, and leaving school before completion (Clarke, 2002). The death rate for Native American adolescents is twice that of adolescents of other racial or ethnic backgrounds and for Native American adolescent males, the rate is nearly three times higher (Garrett & Carroll, 2000). Furthermore, most of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality for Native American adults can be traced to the health compromising behaviors of adolescence

Socio-economically disadvantaged, 31.6% of Native Americans live below the poverty line, compared with 13.1% for all races in the United States (Commission on Civil Rights, 2004). Cherokees, compared to non-Native Americans living in Oklahoma, report significant lower income levels which has been determined to contribute to significant higher disease rates such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and substance abuse (Campbell, 2005). Native American adolescents are exposed to a variety of continuous stressors such as poverty and family disruption. Many of these youth will also experience stress specifically associated with being a member of an ethnic minority group in the United States, such as racism, discrimination, transgenerational trauma, and post-colonial oppression (Duran & Duran, 1995; Gonzales & Kim, 1997; Walters & Simoni, 2002; Braveheart, 2003).

Stress and coping processes have been reported to play an important role in the physical and mental health outcomes of Native Americans (Walters & Simoni, 2002). Native American youth have significantly greater emotional distress than their white peers, and much of their distress is related to social and cultural factors (Bergstrom, Miller, & Peacock, 2003). Social change has been widespread in Native American populations as well, challenging the traditional way of life, values, and relational systems. The Native American family is changing rapidly as family members must now work and go to school outside of the home and community. This threatens the traditional closeness of the family. In earlier years, families worked closely together to survive in hostile environments (Frank, Moore, & Ames; 2000). Many Cherokee elders and leaders report that the interdependence, Cherokee self-reliance, of the family, clan, and the tribe of earlier years has eroded (Lowe, 2002). Cherokee adolescents have reported high levels of stress which served as a contributing factor to substance abuse (Lowe, 2006).

Many intervention models that utilize coping strategies for stress fail to consider how socio-economic and cultural factors can impact Native Americans ability to cope with stress. More research is needed to understand how stress and coping occurs across social and cultural groups. In particular, there is a lack of literature focusing on how Native American youth cope with stress.

Cherokee Self-Reliance

Self-reliance is a concept within the Cherokee holistic worldview where all things are believed to come together to form a whole (Mankiller, 1991). Leaders of the Cherokee Nation have noted self-reliance to be the mainstay and way of life that influences health and helps to keep balance among the Cherokee (Stuart, 1993). The goal of self-reliance is included in the 1976 mission statement of the Cherokee Nation constitution (Resolution No. 28-85, 1976).

Knowledge of the historical background and distinct culture of Native Americans have been noted as important factors if one wishes to increase understanding of Native Americans today (Mankiller, 1991). Historically, the Cherokee inhabited the southeast region of the United States that now includes the states of Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama (Mooney, 1982). The way of life and roles of the Cherokee changed dramatically as a result of the dispossession of land and culture through government treaties and force of arms. The forced removal known as the Trail of Tears, and the establishment of the Indian Boarding Schools were among the events that undermined the self-reliance of the Cherokee. For example, traditional dress and speaking the tribal language was prohibited in an attempt to strip the Cherokee of her/his identity. As a result, the physical, emotional, psychosocial, economic, and spiritual well-being of the Cherokee continues to bear witness to dispossession today.

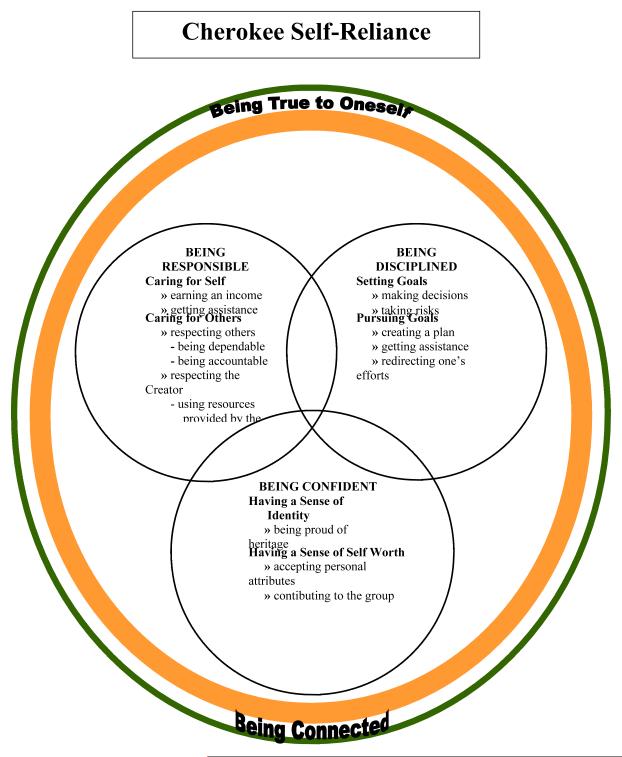

The Cherokee Self-Reliance Model was developed from findings of studies that explored the meaning of how self-reliance is conceptualized by the Cherokee (Lowe, 2002, 2003, 2005). The perspective of self-reliance endorsed by the Cherokee is a composite of three categories that include: (a) being responsible, (b) being disciplined, and (c) being confident. Being responsible refers to being responsible to care for oneself and to care for others by getting assistance, respecting self, respecting others and respecting the Creator. Respecting others occurs by being dependable and being accountable. Honoring Cherokee traditions, values, and language is away to respect the Creator. Being disciplined refers to setting goals and pursing goals by taking the initiative to make decisions and taking risks. After decisions are made and goals are set, the pursuit of goals occurs by creating a plan, getting assistance, and redirecting one’s effort. Being confident refers to having a sense of identity and self-worth. Knowing who one is as a Cherokee relates to being proud of one’s heritage with strong values and beliefs that are consistent with Cherokee values and beliefs. There are two cultural themes that cut across all three categories which include: (a) being true to oneself, and (b) being connected. For the Cherokee, self-reliance is developed by: (a) being supported, (b) being instructed, and (c) being sponsored. Figure 1 presents the Cherokee Self-Reliance Model, which portrays the interrelatedness of the three categories.

Figure 1. Cherokee Self-Reliance Model.

The model of Cherokee Self-Reliance is formed in a circle indicating the circular holistic world view of Cherokee culture. The outside circle is green which symbolizes an oak wreath. The orange inner circle symbolizes the sacred eternal fire. The live oak, the traditional principal hardwood timber of Cherokee people, was used to kindle the sacred fire. In connection with this fire, the oak was a symbol of strength and everlasting life. These colors are used in the seal of the Cherokee Nation. The three interlocking circles in the center of the model depicts the interrelatedness, intertwining, and interlacing of all of the categories and subcategories of the cultural domain of Cherokee Self-Reliance.

Method

A descriptive correlation design was used to examine the relationship between Cherokee self-reliance and word-use in stories of stress. The overall aim of this pilot study was to test the feasibility of using cultural appropriate measurements for a larger intervention study of substance abuse prevention in Cherokee adolescents. The specific research question for this analysis was: What is the relationship between Cherokee self-reliance and self-other, cognitive process, achievement, and positive/negative word-use in stories of stress shared by Cherokee adolescents?

Instrumentation

Cherokee self-reliance was measured using the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire (Lowe, 2003). The Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire includes 24-items that are rated using a Likert scale and has been utilized in previous research (Lowe, 2006, 2008). This instrument has a Cronbach alpha coefficient of .84. Consistent with the Cherokee self-reliance concept, the instrument reveals three factors: being responsible, being disciplined, and being confident.

Stress was measured using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), a narrative analysis software. Written stories of stress were gathered in a 15-minute period using standardized guidance. Cherokee adolescents were given directions to write about: what they think about stress; how they feel about it, and how they managed their stress. They were also told that the most important thing to share was how things were going for them in relation to the stress in their life. They were instructed not worry about grammar, spelling or sentence structure. Once they began to write, students continued to do so for 15 minutes. If the participating students ran out of things to write, they were asked to repeat what they have already written. The written stories were transcribed and prepared for analysis with LIWC software (Pennebaker, Francis & Booth, 2001).

The LIWC program is a word-based computerized text analysis software, which discerns 72 linguistic categories, including the ones pertinent to this analysis (self/other, achievement, cognitive process, positive/negative emotion). The reliability and validity of word categories has been extensively tested using panels of judges, factor analysis methods and criterion related validity procedures (Pennebaker & King, 1999). LIWC reports the percentage of words-used in the selected word categories in relation to all the words used by a participant

Sample and Procedure

A sample of 50 Cherokee students participated in this study. They were recruited from Cherokee adolescent senior high school students attending two public high schools within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. Inclusion criteria included: Cherokee heritage/tribal affiliation, senior student status, willingness to participate, and active parental and student consent. Approval to conduct the study was received from the Institutional Review Board of the affiliating university and the High School administration.

The Cherokee adolescent high school students participating in the study from both schools were asked to complete the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire and write their story of stress in a private room with a research assistant who guided them when they had questions about completing the instruments. The student participants were first given 30 minutes to complete the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire and then 15 minutes to complete the written stories of stress.

Results

The purpose of this study was to consider the relationship between Cherokee self-reliance and related values expressed through word-use in stories of stress written by Cherokee adolescents. In particular, the use of: (a) self/other words (being responsible); (b) cognitive process and achievement words (being disciplined); and (c) positive/negative emotion words (being confident) were considered. Table 1 displays the Cherokee self-reliance concepts that are associated with word categories, example of words, and descriptive data.

Table 1.

Self-reliance concepts with associated word categories, example words and descriptive data

| Self- reliance concepts | Associated word categories and example words |

Cherokee adolescent word category descriptive data |

|---|---|---|

|

Being responsible refers to caring for oneself and others; assumes valuing for interdependence emerging from “being connected.” |

|

|

|

Being disciplined refers to setting and pursuing goals; assumes thoughtful decision-making to create a personally- relevant plan. |

|

|

|

Being confident refers to having a sense of identity and self-worth; assumes a feeling of being proud and strong. |

|

|

Each story of stress was prepared for analysis, using standardized guidelines, including spell check and assurance of at least 40 words for each writing (Pennebaker, Francis & Booth, 2001). When a written word could not be discerned, it was represented with “xxx” according to guidelines so that it would be counted as a word but not placed into a meaningful category. Overall, 82% of the written words of Cherokee adolescents were captured for this analysis. Only word-use categories with values of 1% or higher were used in the analysis. Data were analyzed using two-tailed Pearson correlations.

Word-use associated with the Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire category of “being responsible” was most often significantly (p < .05) related to self-reliance; “I” and “self” word-use was negatively correlated, r = −.31 and r = −.29, respectively while “other reference” word-use was positively (r = .30) correlated. The category of “being disciplined” word-use was not significantly associated with self-reliance in this sample. However, the use of “family” words was negatively related (p < .05) with “affect” (r = −.32), “negative emotion” (r = −.33) and “anxiety” (r = −.36) word-use. For word-use associated with the category of “being confident,” there was a significant positive relationship (r = .32, p < .05) between “affect” word-use and self-reliance.

Discussion

The Cherokee Self-Reliance Model’s three major categories help to explain the findings in the study. The first category of being responsible refers to how Cherokees care for self and others and assumes the value for interdependence that emerges from being connected. Consistent with this concept, the higher the level of Cherokee self-reliance demonstrated by the Cherokee adolescent participants, the lower the use of “I” and “self” words and the higher use of other-reference words. Self-reliance for the Cherokee is a holistic concept where the Cherokee views themselves as part of all of the creation. This involves being a part of a family, community and tribe. The Cherokee person is much greater than just their individual selves. In fact, Cherokee adolescents who used a higher percentage of “family” words in their stories of stress used fewer “affect”, “negative emotion” and “anxiety” words. Pennebaker and Stone (2003) propose word-use as a window into an individual’s personality. With this in mind, the family-affect relationship finding suggests that mention of family in the language of Cherokee adolescents is associated with a calming and positive spirit.

The second category of being disciplined refers to how the Cherokee sets and pursues goals. According to the Cherokee worldview, life is considered to be a process of being and becoming. Setting and pursuing goals is an important aspect of the lifelong process of being and becoming. This long process may not be easily captured or reflected in a few written words. This may explain why the word-use in this sample was not significantly associated with this category. It is also possible that the cognitive process words selected to address being disciplined were not a good match for the concept. It would be worthwhile to explore the match in a larger study particularly after adolescents had been supported to live Cherokee self-reliance.

The third category of being confident relates to the Cherokee having a sense of identity and self-worth. This is reflected in having a sense of knowing who one is as a Cherokee which is related to being proud of one’s heritage with strong values and beliefs. The findings of other studies reveal that the more Native Americans are aware of their heritage and culture, the more the tendency to strongly possess and express both positive and negative emotions. This can be related to the awareness and reality of the stress as a result of the dispossession that occurred and the subsequent consequences, such as diseases, poverty and other socioeconomic disadvantages Additionally, strong tribal, community and family relationships continue to be a part of Native Americans lived experienced today (Lowe, 2006, 2008; Bertolli et al., 2004). The adolescents in this sample showed a significant positive correlation between affect word-use and Cherokee self-reliance. The affect word-use category includes both positive and negative feelings, and may best be described as an indicator of feeling expression. So, adolescents who had a strong sense of Cherokee self-reliance were most likely to express their feelings, a finding that is consistent with expectations related to being confident.

Conclusion

The Cherokee Self-Reliance Questionnaire and LIWC show promise for continuing use in longitudinal and/or experimental research. Guided by the Cherokee Self-Reliance Model, this research indicates that LIWC word categories are most sensitive to the “being responsible” concept and least sensitive to the “ being disciplined” category. Additional research can help researchers to further evaluate the use of LIWC to capture the essence of Native American stories for analysis in relation to meaningful health indicators. Data derived from the use and testing of both of these measurement approaches (Cherokee self-reliance; LIWC) has the potential to yield more culturally relevant and valid information, establishing a base for intervention evaluation that reflects unique qualities of the Native American cultural group.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (No. 1R01DA021714-01A2)

Contributor Information

John Lowe, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing Florida Atlantic University.

Cheryl Riggs, Central Public Schools.

Jim Henson, Interventionist and Community Liaison.

Patricia Liehr, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing Florida Atlantic University.

References

- Bergstrom A, Cleary L, Peacock T. The seventh generation: Native students speak about finding the good path. ERIC/CRESS; Charleston, WV: 2003. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED472385) [Google Scholar]

- Bertolli J, McNaghten A, Campsmith M, Lee L, Leman R, Bryan R, et al. Surveillance systems monitoring HIV/AIDS and HIV risk behaviors among American Indians and Alaska Natives. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(3):218–237. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.218.35442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveheart MYH. The historical trauma response among Natives and its relationships with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. Assessing health disparities: The Oklahoma Minority Health survey. 2005. (Available from the Oklahoma State Department of Health. 1000 NE 10th Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73117)

- Clarke A. Social and emotional distress among American Indian and Alaska Native students: Research findings. ERIC Digest. ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools; Charleston, WV: 2002. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED459988) [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Duran B. Native American postcolonial psychology. State University of New York Press; NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Moore R, Ames G. Historical and cultural roots of drinking problems among American Indians. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(3):344–351. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett M. Walking on the wind: Cherokee teachings for harmony and balance. Bear and Co.; Rochester, VT: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Kim LS. Stress and coping in an ethnic minority context. In: Wolchik SA, Standler IN, editors. Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention. Plenum Press; NY: 1997. pp. 481–511. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. Cherokee self-reliance. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13(4):287–295. doi: 10.1177/104365902236703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. The self-reliance of the Cherokee adolescent male. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2003;14:209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. Being influenced: A Cherokee way of mentoring. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2005;12(2):37–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. Teen Intervention Project – Cherokee (TIP-C) Pediatric Nursing. 2006;32(5):495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J. A cultural approach to conducting HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C virus education among Native American adolescents. Journal of School Nursing. 2008;24(4):229–238. doi: 10.1177/1059840508319866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankiller W. Education and Native Americans: Entering the twenty-first century on our own terms. National Forum:Phi Kappa Phi Journal. 1991;71(2):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney J. Myths of the Cherokee and sacred formulas of the Cherokees. Charles Elder Book Seller; Nashville, TN: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Booth RJ, Francis ME. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, King LA. Linguistic styles: Language use as an individual difference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(6):1296–1312. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Stone LD. Words of Wisdom: Language use over the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:291–301. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mission statement: Constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Cherokee Nation; Tahlequah, OK: 1976. Resolution No. 28-85. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer P. Culture and the restoration of self among former American Indian drinkers. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;53(2):227–240. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Commission on Civil Rights [Retrieved January 10, 2009];Broken Promises: Evaluating the Native American health care system. 2004 from http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/nahealth/nabroken.pdf.

- Walters K, Simoni J. Reconceptualizing native women’s health: An indigenist stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):520–524. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]