Abstract

Context

No randomized, controlled, prospective study has evaluated the effect of growth hormone (GH) on the rates of middle ear (ME) disease and hearing loss in girls with Turner syndrome (TS).

Design

A 2-year, prospective, randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter, clinical trial (‘Toddler Turner Study’; August 1999 to August 2003) was carried out.

Setting

The study was conducted at 11 US pediatric endocrine centers.

Subjects

Eighty-eight girls with TS, aged 9 months to 4 years, were enrolled.

Intervention

The interventions comprised recombinant GH (50 μg/kg/day, n = 45) or no treatment (n = 43) for 2 years.

Main Outcome Measures

The outcome measures included occurrence rates of ear-related problems, otitis media (OM) and associated antibiotic treatments, tympanometric assessment of ME function and hearing assessment by audiology.

Results

At baseline, 57% of the girls (mean age = 1.98 ± 1.00 years) had a history of recurrent OM, 33% had undergone tympanostomy tube (t-tube) insertion and 27% had abnormal hearing. There was no significant difference between the treatment groups for annual incidence of OM episodes (untreated control: 1.9 ± 1.4; GH-treated: 1.5 ± 1.6, p = 0.17). A quarter of the subjects underwent ear surgeries (mainly t-tube insertions) during the study. Recurrent or persistent abnormality of ME function on tympanometry was present in 28–45% of the girls without t-tubes at the 6 postbaseline visits. Hearing deficits were found in 19–32% of the girls at the annual postbaseline visits. Most of these were conductive deficits, however, 2 girls had findings consistent with sensorineural hearing loss, which was evident before 3 years of age.

Conclusions

Ear and hearing problems are common in infants and toddlers with TS and are not significantly influenced by GH treatment. Girls with TS need early, regular and thorough ME monitoring by their primary care provider and/or otolaryngologist, and at least annual hearing evaluations by a pediatric audiologist.

Key Words: Turner syndrome; Somatropin; Conductive hearing loss; Sensorineural hearing loss; Tympanostomy tube; Otitis media, child; Preschool

Introduction

Turner syndrome (TS), one of the most common human genetic disorders, occurs in approximately 1:2,000 live female births [1]. Affected phenotypic females have a range of problems caused by loss of all or part of the second sex chromosome, specifically, its distal short arm, including short stature, gonadal failure, hearing loss, cardiovascular abnormalities and nonverbal learning disabilities [2]. Of the many chronic health problems faced by individuals with TS, ear disease and hearing loss are among the most significant and troublesome [3,4]. Although a number of cross-sectional, mainly retrospective, studies have reported an increased prevalence of otitis media (OM) and hearing loss in school-aged girls and women with TS [[5,6,7,8,9], reviewed in [10]], no large-scale, prospective study has investigated the prevalence and natural history of ear disease and hearing loss in infants and toddlers. The paucity of data in very young girls is of particular concern given the susceptibility of children in this age group to middle ear (ME) disease and the importance of the preschool years for learning and language development [11].

Recombinant growth hormone (GH) is commonly used to treat short stature in children with TS [3] and a potential influence of GH treatment on ear disease was suggested by 2 GH trials in which OM and other ear disorders were reported as adverse events (AEs) with greater frequency for the GH-treated than non-GH-treated girls [12,13]. However, the significance of these findings was unclear, as neither study was designed to prospectively investigate the effect of GH treatment on ear disease, thus the data were gleaned from clinical trial AE reports, rendering them potentially subject to various reporting biases [14]. Given the limitations of these studies, further data are required to clarify the effect, if any, of GH treatment on ear disease in young girls with TS. We hypothesized that GH therapy would decrease, rather than increase, the prevalence of OM and conductive hearing impairment in girls with TS by improving the growth and development of the ME system. Therefore, the aims of this study were to prospectively evaluate the effects of 2 years of GH treatment on the rates of acute OM, abnormal ME function and hearing loss in a large cohort of infants and toddlers with TS.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This prospective, randomized, controlled, open-label study (Clinical Trial Registry number: NCT00406926), conducted between August 1999 and August 2003, was approved by the review boards of the 11 participating institutions in the USA, and performed in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The primary aim of the study, on which the sample size was calculated, was to determine whether early initiation of GH treatment in girls with TS aged 9 months to 4 years could prevent the growth failure that otherwise occurs [15]. As a prespecified secondary objective, this study sought to determine in a prospective fashion whether GH treatment would reduce the rates of ME disease and/or hearing loss in this population. However, it should be noted that the study was not formally powered to address these secondary objectives.

Subjects

Subjects were eligible to participate if they: were aged between 9 months and 4 years; had karyotype-proven TS; had written informed consent from their legal guardian(s) and were excluded if they had any Y chromosomal component in the karyotype and gonads in situ or were receiving any concurrent treatment that might influence growth [15].

Treatment Intervention

Using a phone-in, interactive voice response system, the subjects were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either a nontreatment control group or a GH treatment group. The GH group received daily subcutaneous injections of 50 μg/kg of recombinant human GH (somatropin, rDNA origin; Humatrope®, Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Ind., USA); the control group received no injections. A 10-year extension study of this cohort was initiated in 2005.

Measures

Sociodemographic data were collected at baseline for a number of variables that could influence susceptibility to ear disease (table 1), including parental education level (a marker of socioeconomic status) [16], number of siblings in the home, average number of children in the child's daytime location, daytime environment (e.g. own home, other home setting, day care facility) and the presence of a smoker in the home [17]. After a detailed baseline evaluation, the subjects were followed at approximately 4-month intervals for 2 years.

Table 1.

Baseline historical, clinical and sociodemographic data

| Baseline characteristic | Nontreatment (n = 43) | GH treatment (n = 45) | All (n = 88) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Karyotype | |||

| 45,X | 29 (67) | 27 (60) | 56 (64) |

| 45,X/46,XX | 7 (16) | 7 (16) | 14 (16) |

| Other | 7 (16) | 11 (24) | 18 (20) |

| Medical history | |||

| Breast fed <3 months | 24 (56) | 25 (56) | 49 (56) |

| Craniofacial anomaly | 3 (7) | 9 (20) | 12 (14) |

| Recurrent ear infection | 24 (56) | 26 (58) | 50 (57) |

| Tympanostomy tubes | 13 (30) | 16 (36) | 29 (33) |

| Tonsillectomy | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Adenoidectomy | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Cholesteatoma | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Mastoiditis | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Exposure to ototoxic druga | 3/42 (7) | 4/43 (9) | 7/85 (8) |

| Clinical | |||

| Tympanostomy tube(s) present | 10/41 (24) | 12/44 (27) | 22/85 (26) |

| Abnormal ME function by tympanometry (1 or both ears)b | 17/28 (61) | 18/27 (67) | 35/55 (64) |

| Abnormal hearing on audiometry (1 or both ears) | 8/38 (21) | 13/41 (32) | 21/79 (27) |

| Chronological age, years | 1.97 ± 1.01 | 1.98 + 1.01 | 1.98 ± 1.00 |

| Height SDS | −1.76 ± 1.07 | −1.42 ± 1.00 | −1.59 ± 1.04 |

| Weight SDS | −1.77 ± 1.46 | −1.31 ± 1.18 | −1.54 ± 1.34 |

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Parental education at least high school | |||

| Mothers | 42 (98) | 44 (98) | 86 (98) |

| Fathers | 42 (98) | 44 (98) | 86 (98) |

| Both parents at home | 41 (95) | 39 (87) | 80 (91) |

| Siblings at home | |||

| 0 | 11 (26) | 13 (29) | 24 (27) |

| 1 | 19 (44) | 11 (24) | 30 (34) |

| 2 | 8 (19) | 15 (33) | 23 (26) |

| 3 | 4 (9) | 2 (4) | 6 (7) |

| ≥4 | 1 (2) | 4 (9) | 5 (6) |

| Subject's daytime location | |||

| Own home | 33 (77) | 36 (80) | 69 (78) |

| Other home | 6 (14) | 4 (9) | 10 (11) |

| Agency | 4 (9) | 5 (11) | 9 (10) |

| Children in daytime setting Subject only | 9 (21) | 17 (38) | 26 (30) |

| 2-3 | 23 (53) | 17 (38) | 40 (45) |

| 4-7 | 5 (12) | 4 (9) | 9 (10) |

| ≥8 | 6 (14) | 7 (16) | 13 (15) |

| Smoker in subject's home | |||

| No | 28 (65) | 37 (82) | 65 (74) |

| Yes | 15 (35) | 8 (18) | 23 (26) |

Values are numbers of cases with percentages (in parentheses) of the number of subjects in each group with available data, or means ± SD. There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups. SDS = Standard deviation score.

Data were missing for 3 subjects.

Numbers reflect only children without t-tubes, as t-tubes are intrinsically associated with altered tympanometry profiles.

The outcomes of primary interest for this analysis were the occurrence rates of OM, ME dysfunction (defined below) and hearing loss. To obtain detailed information on ear-related events between the 4-month study visits, the girls’ families were provided with diaries specifically designed for the collection of data regarding ear status. The parents were instructed to record all visits to health care providers for any ear-related concerns and all antibiotic prescriptions for new ear problems. Diary information was entered into the case report forms by the study coordinators at each visit. In addition, standard AE reports were collected and the families were specifically asked at each study visit whether the child had experienced any of the following ear, nose and throat (ENT)-related events since the previous visit: head trauma with loss of consciousness or skull fracture, tympanostomy tube (t-tube) insertion, other ear surgery (e.g. myringotomy, t-tube removal), cholesteatoma, mastoiditis, tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy or exposure to ototoxic medications (salicylates, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aminoglycosides, erythromycin, vancomycin, capreomycin, metronidazole, loop diuretics). The occurrence rate and duration of OM for each subject were determined by detailed evaluation of the subjects’ diary information and AE reports, which were reviewed by 1 of the authors (M.L.D.) to determine the events that represented OM (e.g. ‘middle ear infection’, ‘right otitis media’) versus other events (e.g. ‘left ear bleeding’, ‘ear pain’).

Ear examinations using a pneumatic otoscope (model 20200 3.5V, Welch Allyn Inc., Skaneateles Falls, N.Y., USA) were performed at each visit for the presence or absence of acute OM, tympanic membrane perforation(s) and t-tube(s). Because we were interested in abnormalities of ME function as well as effusion, assessment at each visit by tympanometry (GSI 38 Auto-Tymp, Grason-Stadler Inc., Milford, N.H., USA) included 2 acoustic immittance measures known to be highly sensitive to abnormalities of ME function – peak compensated acoustic admittance and tympanometric width [18]. Acoustic admittance magnitude was measured in acoustic millimhos over an ear canal pressure range of +200 to −400 daPa. Tympanometry results were considered abnormal, representing ME dysfunction, under the following conditions: for children ≤1 year of age: static admittance <0.2 mmho and/or tympanometric width >235 daPa; for children >1 year old: static admittance <0.3 mmho and/or tympanometric width >200 daPa [19,20,21,22]. The t-tubes were considered patent when a flat tympanogram was accompanied by an equivalent volume >1.0 ml [23]. An individual child was designated as having abnormal ME function if tympanometric analysis was abnormal for 1 or both ears.

In addition to the 4-monthly assessments for ME disease, hearing was evaluated annually by an audiologist in an acoustically controlled test room using calibrated equipment. A member of the research team (J.R.) provided detailed age-specific audiology protocols and consulted with the audiologists as needed. In general, girls <2.5 years old were assessed using visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) in sound field, which tests binaural hearing sensitivity but cannot differentiate one ear from the other. The test stimuli comprised warbled pure tones (500, 1,000, 2,000 and 4,000 Hz) delivered by loudspeaker. Because responses to this testing reflect hearing in the better ear, hearing was assumed to be abnormal in both ears if the mean hearing thresholds across the test frequencies were >25 dB hearing level (HL). Older girls (≥2.5 years) were assessed using conditioned play audiometry (CPA), which was used to test each ear independently via earphones and included a broader range of air-conducted pure-tone stimuli (250, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 4,000 and 8,000 Hz); hearing was considered abnormal in an ear if the mean hearing thresholds obtained across the test frequencies were >20 dB HL. An individual child was designated as having abnormal hearing sensitivity if her hearing was abnormal on either VRA (ear undetermined) or for one or both ears on CPA. Because of the longitudinal nature of the study and the increasing age and developmental level of the girls over its 2-year duration, data from VRA and CPA were combined for analysis.

Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) was assayed by Esoterix Endocrinology (Calabasas Hills, Calif., USA) on blood samples obtained at baseline, as well as 4, 12 and 24 months [15].

Statistical Methods

The occurrences of OM based on diary information and AE reports were summarized for number and duration of OM events per subject, per year. To determine age-related patterns of OM, the frequency and duration of these events were analyzed for the following age groups: <2, 2 to <3, 3 to <4, 4 to <5 and ≥5 years, using means weighted by the amount of time spent by each subject within the age interval.

ME function (tympanometry) was summarized for percent of subjects at each visit (and across all postbaseline visits) with normal results, findings consistent with t-tube(s), abnormal findings or missing data. The results of annual hearing tests were summarized for percent of subjects with abnormal hearing (see ‘Measures’), with or without associated ME dysfunction, at baseline, and 12 and 24 months.

Associations were evaluated between sociodemographic characteristics, IGF-I standard deviation score (SDS) and history of recurrent OM, number of on-study days of OM, abnormal ME function and hearing loss at baseline and endpoint using Pearson correlations. Between-group comparisons for continuous variables (e.g. age, IGF-I SDS) were made using an independent-group t test or analysis of variance with baseline age group (<2.5 or ≥2.5 years) and treatment group as explanatory variables. Unless stated otherwise, continuous data are reported as means ± 1 standard deviation (SD). Between-group comparisons for categorical variables were made with Fisher exact tests. All tests were 2-sided and conducted at the 0.05 level of significance. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software system (version 8.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Of the 88 girls with karyotype-proven TS randomized in the study, 87 (control: n = 42; GH: n = 45) had postbaseline data available and 78 completed the 2-year study. The primary efficacy and safety data have been reported [15].

Baseline Data

At study entry (mean age = 1.98 ± 1.00 years), 50/88 (57%) of the girls already had a history of recurrent OM, 29/88 (33%) had undergone t-tube insertion and 22/85 (26%) had t-tube(s) visible by otoscopy (table 1). Given the known detrimental effect of cigarette smoke on ME function, it was notable that 23/88 girls (26%) had a smoker in the home. By tympanometric evaluation (categorized as: normal, functional t-tube, abnormal or unsuccessful), 19/87 girls (22%) were normal, 19/87 girls (22%) had abnormal ME function characteristic of functional t-tubes, 35/87 (40%) had other abnormal ME findings and 14/87 girls (16%) had unsuccessful tests. Furthermore, hearing was abnormal for 21/79 (27%) of the girls. Not surprisingly, there were significant positive baseline associations between the presence of t-tube(s) and a history of recurrent OM (p = 0.0001) and between the presence of t-tube(s) and ME dysfunction (p = 0.04). Interestingly, subjects with a baseline history of recurrent OM had a significantly lower mean IGF-I SDS than those without such history (−0.59 ± 0.90, 95% CI = −0.86 to −0.32 versus 0.05 ± 0.76, 95% CI = −0.22 to 0.32, p = 0.0015). However, this finding was not associated with any significant difference in prestudy growth, as baseline weight SDS, length SDS and BMI were similar for girls with or without a history of recurrent OM (without OM history: length SDS = −1.6 ± 1.1, weight SDS = −1.9 ± 1.3, BMI = 16.23 ± 1.22; with OM history: length SDS = −1.6 ± 1.0, weight SDS = −1.3 ± 1.3, BMI = 16.46 ± 1.41). There was no association between any of the ear disease measures and karyotype or other baseline characteristics.

On-Study (Postbaseline) Data

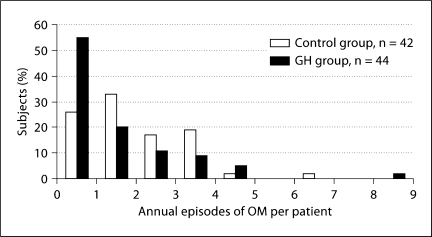

Otitis Media. Most girls (87%) had at least 1 episode of OM during the 2-year study period. The average annual number of OM events per subject was: control: 1.9 ± 1.4; GH: 1.5 ± 1.6 (p = 0.17; table 2). Whereas 55% of the GH-treated girls had ≤1 episode of OM per year, this was true for only 26% of the girls in the control group (fig. 1). The episodes of OM tended to be quite lengthy (average days: control: 15.8 ± 16.7; GH: 18.2 ± 24.9, p = 0.34). The average number of days per year with OM was similar for the control and GH groups (31.8 ± 30.0 vs. 25.7 ± 31.7; p = 0.36). Based on data from subject diaries, antibiotics for new ear-related problems were prescribed approximately once every 4 months in both groups.

Table 2.

Annual number and duration of OM events by age group

| Nontreatment (n = 42)∗ | GH treatment (n = 45) | |

|---|---|---|

| Episodes per year by age group | ||

| <2 years | 2.8 (1.6) | 2.2 (1.4) |

| 2 to <3 years | 2.0 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.7) |

| 3 to <4 years | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.3) |

| 4 to <5 years | 1.4 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.0) |

| ≥5 years | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.3 (2.2) |

| Average for all agesa | 1.9 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.6) |

| Days per year by age group | ||

| <2 years | 50.9 (43.2) | 31.1 (24.0) |

| 2 to <3 years | 26.6 (25.3) | 28.5 (47.1) |

| 3 to <4 years | 25.7 (36.4) | 21.3 (26.8) |

| 4 to <5 years | 21.7 (39.9) | 13.1 (17.5) |

| ≥5 years | 8.8 (9.3) | 25.7 (29.4) |

| Average for all agesb | 31.8 (30.0) | 25.7 (31.7) |

Data are provided as means (SD).

One subject who had no post-baseline data was excluded.

p = 0.17

p = 0.36: between-group difference.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of annual number of episodes of OM per subject. The distribution is shifted to the left somewhat (fewer episodes) for the GH group compared with the control group (p = 0.08).

When evaluated by age group (<2, 2 to <3, 3 to <4, 4 to <5 and ≥5 years) the average annual number of OM events and cumulative days of OM showed declining trends, as would be expected with increasing age (table 2). However, the number of days with OM was highly variable, ranging from 0 to 146 days per subject per year; there were no significant between-group differences for age-related rates or durations of OM.

Ear-Related AEs. As expected in a TS cohort, ear-related events were common. More than a third of the subjects (32/87; 17 control, 15 GH) underwent ≥1 ear surgeries (mainly t-tube insertions with occasional t-tube removals and stand-alone myringotomies) during the study. In addition, 16/87 girls (18%) (control: 7; GH: 9) underwent tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. There were few case reports for any of the other prespecified events and no significant between-group differences on a by-visit or cumulative basis.

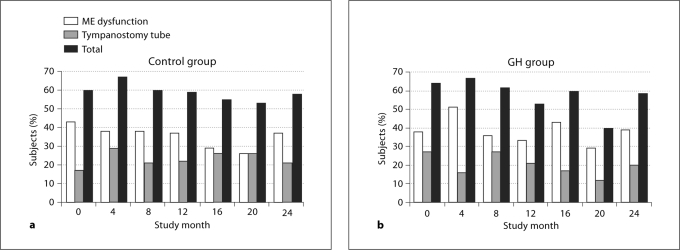

ME Function (Tympanometry). ME dysfunction was common in this young cohort, being present in 28–45% of the subjects overall at the 6 post-baseline visits (control: 34 ± 5%; GH: 39 ± 8%, NS). Whereas t-tube(s) were observed by otoscopy in 32–44% of the subjects at the 6 postbaseline visits, only 19–24% had tympanometric profiles consistent with functional t-tubes, suggesting that many of the t-tubes had become occluded. The frequency of ME dysfunction was not influenced by GH treatment, as there was no significant difference between the treatment groups at any postbaseline visit (fig. 2). Tympanometry was unsuccessful about a quarter of the time (29 ± 7% of the control girls and 24 ± 7% of the GH-treated girls across the 6 postbaseline visits) because of the age and cooperation levels of the subjects. Therefore, the percentages of subjects whose findings were consistent with t-tubes or ME dysfunction are likely underestimates.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of subjects in the control (a) and GH (b) group at each visit who had evidence of ME dysfunction by tympanometry (1 or both ears); t-tube(s) in 1 or both ears and total percentage of subjects with abnormal tympanometry. There were no significant between-group differences at any study visit for rates of abnormal tympanometry or presence of tympanostomy tubes.

Hearing. The proportion of subjects with abnormal hearing was high throughout the study and did not differ significantly between the groups (table 3). As expected in this young population, the hearing deficit appeared to be conductive in nature, as suggested by the coexistence of ME dysfunction with hearing loss in most affected girls (table 3). Although the prevalence of hearing loss increased somewhat from baseline to endpoint in the controls (15 → 21%) and decreased moderately in the GH-treated subjects (35 → 17%), the between-group differences were not significant (table 3).

Table 3.

Hearing and ME function at baseline and at the final study visit

| Baseline visit |

Final visit |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nontreatment (n = 34) | GH treatment (n = 37) | All subjects (n = 71) | Nontreatment (n = 28) | GH treatment (n = 30) | |

| Normal hearing | 29 (85) | 24 (65) | 53 (75) | 22 (79) | 25 (83) |

| With normal ME function | 12 (35) | 6 (16) | 18 (24) | 8 (29) | 8 (27) |

| With patent t-tubesa | 7 (21) | 6 (16) | 13 (18) | 6 (21)b | 4 (13)b |

| With abnormal tympanometryc | 10 (29) | 12 (32) | 22 (31) | 8 (29) | 13 (43) |

| Bilateral hearing lossd | 5 (15) | 13 (35) | 18 (25) | 6 (21) | 5 (17) |

| With normal ME function | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| With patent t-tubesa | 0 (0) | 4 (ll)b | 4 (6)b | 2 (7) | 2 (7) |

| With abnormal tympanometryc | 5 (15) | 7 (19) | 12 (23) | 4 (21) | 2 (13) |

Figures are numbers of cases with percentages (in parentheses) of subjects with results available in each group. Subjects were included in this analysis only if they had both tympanometry and audiometry results available at the same visit. There was no significant difference between treatment groups for the prevalence of hearing deficit at any study visit.

t-tubes were considered patent when a flat tympanogram was accompanied by an equivalent volume >1.0 ml in a subject with t-tube visible on otoscopy

One subject in each group also had a tympanic membrane perforation on otoscopy.

Tympanometry was considered abnormal for subjects <1 year of age if static admittance was <0.2 mmho and/or tympanometric width >235 daPa. For subjects ≥1 year of age, ME function was considered abnormal if static admittance was <0.3 mmho and/or tympanometric width >200 daPa.

Hearing was considered abnormal if the mean hearing levels were >25 dB HL by VRA or >20 dB HL by CPA. Results are provided for bilateral hearing loss because assessment by VRA performed in sound field reflects the sensitivity of the better ear and this will not detect unilateral hearing loss. In addition to the numbers for bilateral hearing loss shown in the table, unilateral hearing loss (determined by CPA) was present for 2 girls at baseline and 7 girls at the last available assessment.

Findings consistent with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL; abnormal hearing in the presence of normal ME function) were present in 2 subjects at baseline. SNHL was subsequently confirmed for 1 participant, whose hearing loss was apparent by 16 months of age. One additional GH-treated subject had audiometry consistent with SNHL at the final study visit at 33 months of age (table 3).

Associations between Ear Disease and Historical, Sociodemographic and Examination Findings. Associations between medical history, sociodemographic variables and examination findings, and the presence or absence of ear disease, were examined by treatment group at the 2-year study endpoint. Although there was a baseline association between history of recurrent OM and IGF-I SDS (described above), there was no correlation between on-study days of OM and endpoint IGF-I SDS. No variables were significantly associated with ME dysfunction by tympanometry. However, abnormal hearing at the endpoint visit in the control group was significantly related to the child's daytime care setting being outside the home (p = 0.0032) and to the presence of >3 additional children in the day care environment (p = 0.0038). These associations were not significant for the GH-treated group.

Discussion

Although many studies have reported data on otologic abnormalities in patients with TS [5,6,7,8,9,10,13,24], none has evaluated ear disease in a large cohort of very young GH-treated vs. untreated girls in a prospective, longitudinal fashion. Thus, the age at onset of ear and hearing problems in TS, and their natural history, have been largely unknown. The study reported here has addressed some of these gaps, demonstrating that significant ME dysfunction, as evidenced by tympanometric abnormalities, was common in these preschool children. Furthermore, by the average age of 2 years (at study entry) approximately 60% of the girls with TS had a history of recurrent OM, compared with the prevalence of 10–20% in infants and preschool children without TS [17,19]. During the 2-year study, the participants had OM for a cumulative period of about 1 full month per year. The associated morbidity was significant, as episodes were often accompanied by pain, perforation, drainage and/or bleeding; doctor visits were frequent and ≥1 antibiotics were usually prescribed for each recorded episode. As recurrent OM predisposes to chronic OM with effusion, it represents a precursor of ME dysfunction and conductive hearing loss (CHL) [5,9,10]. Indeed, consistent with the high rates of OM, t-tube insertion and ME dysfunction were common in our cohort. Furthermore, as a consequence of ME dysfunction, CHL secondary to OM was also frequent, being present in 20–30% of these <6-year-old girls at each of the annual timepoints. One potential limitation of our study was that for logistic reasons, ENT examinations were not performed by otolaryngologists but by the pediatric endocrinologists who participated as principal investigators at the 11 study sites. While we recognize that optimal care for girls with TS should include regular careful assessment by otolaryngologists, we nevertheless believe our results to be reliable, based on the breadth of measures used to assess ME function and hearing in our study.

The increased prevalences of OM and hearing loss in TS appear to result from growth abnormalities of the ME system [25], which includes the eustachian tube and its surrounding structures – the nose, nasopharynx and palate at its proximal end, and the ME and mastoid cells at its distal end. In the typical infant and young child the eustachian tube is shorter overall, has a relatively shorter and narrower osseous portion, less tubal mass and stiffness than in adulthood and lies at a 10-degree angle relative to the horizontal plane. Vertical development of the skull increases the angle of the skull base, allowing the eustachian tube to reach its mature angle of approximately 45° in mid-childhood [26]. It has been hypothesized that the short, flattened cranial base with small poorly pneumatized mastoids in TS results in a relatively shorter, more horizontal eustachian tube, permitting nasopharyngeal reflux and interfering with ME drainage [17,27]. These growth disturbances in TS may result from reduced expression of the X(Y)-chromosomal short-stature homeobox-containing (SHOX) gene [28]. Lacking all or part of the short arm of the second sex chromosome, individuals with TS are haploinsufficient for SHOX. SHOX is highly expressed during normal embryogenesis in the first and second pharyngeal arches [29] (the precursors to the maxilla and mandible, the ossicles and muscles of the ME and the tensor veli palatini, a key muscle in eustachian tube dilation [30]). Abnormalities of these structures (e.g. palatal dysfunction) as well as lymphatic hypoplasia also might contribute to the increased rates of OM in TS.

In addition to high rates of CHL, a high prevalence of SNHL has been reported in older girls and women with TS [7,8,10,24,31,32]. The prevalence of SNHL increases with age; almost 50% of the patients in a Canadian study had evidence of SNHL by 21 years of age [33]and >1 in 4 women with TS require hearing aids [32]. The finding in the present study of probable early-onset SNHL in 2 girls <3 years of age indicates that SNHL may begin very early in some patients, confirming a previous case report of SNHL in a 4-year-old girl [34]. While it has been proposed that the propensity for SNHL in TS may be a consequence of abnormal cochlear development as a result of prolonged cell cycle time associated with chromosomal aneuploidy [27], a study of fetal cochlear development revealed no consistent abnormalities in fetuses with TS up to 23 weeks’ gestation [35]. The combination of the high rates of CHL resulting from ME disease in childhood and progressive SNHL that may begin early in life places patients with TS at high risk for significant hearing deficits throughout life.

As well as carefully assessing the ear and hearing status of a very young group of children with TS, this study sought to evaluate the effect, if any, of 2 years of GH treatment, initiated between 9 months and 4 years of age, on ear disease. This was an important aim because although GH treatment for the short stature associated with TS has been approved in the USA for >13 years, information regarding the effects of GH on ear disease in TS is limited. Two previous randomized studies in school-aged girls had reported higher rates of OM and related ear problems for GH-treated subjects than for control subjects [12,13]. In contrast, we hypothesized that GH therapy would decrease the propensity for ear disease by stimulating growth and development of the cranial base and ME system. Consistent with this hypothesis, a study of 2- to 8-year-old children born small for gestational age found a significant age-dependent effect of GH on growth of the posterior cranial base [36].

Although the present 2-year study did not demonstrate a beneficial effect of GH on ear disease in infants and toddlers with TS, there was no evidence of a detrimental effect. The rates of acute OM, ME dysfunction, hearing loss and other ear-related problems in GH-treated girls in this study were generally similar to, or somewhat lower than, those in non-GH-treated girls. Despite the trend toward lower frequency of ear problems in the GH-treated group, the study was not powered specifically to address the between-group differences in ear disease and may have been underpowered to detect a beneficial GH effect. The findings in the present investigation contrast with those of the earlier studies in school-aged girls [12,13] in which ear problems were more common in GH-treated than untreated girls. These differences are likely due primarily to the detailed prospective data collection employed in the present study versus standard AE reporting in the earlier research. The variation in age of the populations studied may also play a role, given the higher baseline prevalence of ear disease in younger girls. Furthermore, our findings are supported by data from a randomized, controlled GH trial in patients with SHOX deficiency in which the rates of ear disease were similar in the control and GH-treated groups [37].

Our data have clinical implications for the management of young girls with TS. For otherwise healthy children, a history of OM and transient CHL does not appear to adversely affect development; however, these findings cannot be generalized to children at increased risk for developmental delays [38,39]. Considering the higher prevalence of nonverbal learning disabilities in girls with TS and their greater reliance on verbal learning and speech [40], every effort must be made to eliminate or reduce avoidable risk factors for hearing loss such as OM, exposures to cigarette smoke, ototoxic agents or potentially damaging noise levels [11]. Given the need for careful monitoring of hearing and ME function, and the limitations of screening tests for the detection of mild, early-onset cochlear dysfunction [34], all girls with TS should be evaluated for ear disease by their primary care provider and a pediatric audiologist on at least an annual basis, beginning as soon as possible after diagnosis of TS.

In summary, the data reported here highlight the very early onset of significant ear disease, including hearing loss, in infants and toddlers with TS. Furthermore, this study provides the first prospectively collected evidence that GH treatment does not increase the occurrence of ear problems in young girls with TS. Because ear disease has a profound impact on the quality of life in this population, proactive surveillance and aggressive treatment, irrespective of whether or not the child is receiving GH, is essential.

Sources of Support

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Portions of this work were conducted through and supported by the NIH-funded General Clinical Research Center facilities at the University of Washington and Children's Hospital and Regional Medical Center (RR00037), and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, N.C. (RR00046). The authors acknowledge medical writing assistance provided by Proscribe Medical Communications (www.proscribe.com.au), funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague Daniel F. Gunther, M.D. We thank Xingtao Wei for help with statistical analyses and are grateful to the other members of the Toddler Turner Study Group for their dedicated conduct of this study. The members (excluding those mentioned as authors) are listed below alphabetically by the state in which the study site is located: (1) Arkansas Children's Hospital, Ark.: Kathryn M. Thrailkill, MD (previously at University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky.); Sarah Webb, RN (Children's Hospital, Lexington, Ky.); (2) Los Angeles Children's Hospital and University of California, Los Angeles, Calif.: Linda Burkett, RN, Mindy Cahan, RN, Mitchell E. Geffner, MD; (3) Stanford University Medical Center, Stanford, Calif.: Bonnie Baker, LSC; (4) Children's Hospital, Denver, Colo.: Gail Neuenkirchen, RN; (5) Connecticut Children's Medical Center, Hartford, Conn.: Paula Gendreau, RN, Karen Rubin, MD; (6) Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Ill.: Wendy Brickman, MD, Reema L. Habiby, MD, Denise McDaniel, RN; (7) Indiana University/Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis, Ind.: Debbie LeMay, RN; (8) Children's Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, Mo.: Sandy Berg, RN, Carol Huseman, MD; (9) University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C.: Vinnie Duncan; (10) Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pa.: Karen Kowal, RN; Judith Ross, MD; (11) Children's Hospital Medical Center, Seattle, Wash.: Daniel F. Gunther, MD (deceased); Susan Kearns, RN.

Finally, we sincerely thank the girls and their families for their enthusiastic participation in this study.

Footnotes

C.A.Q. and A.J.Z. are employees of Eli Lilly and Company, the sponsor of the Toddler Turner Study. C.L. is a former employee of Eli Lilly & Co.

References

- 1.Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Aarhus, Denmark. Hum Genet. 1991;87:81–83. doi: 10.1007/BF01213097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davenport ML, Calikoglu AS. Turner Syndrome. In: Pescovitz OH, Eugster EA, editors. Pediatric Endocrinology. Mechanisms, Manifestations, and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bondy CA. Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: a guideline of the Turner syndrome study group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:10–25. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carel JC, Ecosse E, Bastie-Sigeac I, Cabrol S, Tauber M, Léger J, Nicolino M, Brauner R, Chaussain JL, Coste J. Quality of life determinants in young women with Turner's syndrome after growth hormone treatment: results of the StaTur population-based cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1992–1997. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Güngör N, Böke B, Belgin E, Tunçbilek E. High frequency hearing loss in Ullrich-Turner syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:740–744. doi: 10.1007/pl00008338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hultcrantz M. Ear and hearing problems in Turner's syndrome. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:253–257. doi: 10.1080/00016480310001097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhooge IJ, De Vel E, Verhoye C, Lemmerling M, Vinck B. Otologic disease in Turner syndrome. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:145–150. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King KA, Makishima T, Zalewski CK, Bakalov VK, Griffith AJ, Bondy CA, Brewer CC. Analysis of auditory phenotype and karyotype in 200 females with Turner syndrome. Ear Hear. 2007;28:831–841. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e318157677f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkin M, Walker P. Hearing loss in Turner syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckman A, Conway GS, Cadge B. Audiological features of Turner's syndrome in adults. Int J Audiol. 2004;43:533–544. doi: 10.1080/14992020400050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeld RM, Culpepper L, Doyle KJ, Grundfast KM, Hoberman A, Kenna MA, Lieberthal AS, Mahoney M, Wahl RA, Woods CR, Jr, Yawn B, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media with Effusion, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Clinical practice guideline: otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:S95–S118. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quigley CA, Crowe BJ, Anglin DG, Chipman JJ, US Turner Syndrome Study Group Growth hormone and low-dose estrogen in Turner syndrome: results of a United States multi-center trial to near-final height. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2033–2041. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephure DK, Canadian Growth Hormone Advisory Committee Impact of growth hormone supplementation on adult height in Turner syndrome: results of the Canadian randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3360–3366. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wernicke JF, Faries D, Milton D, Weyrauch K. Detecting treatment-emergent adverse events in clinical trials: a comparison of spontaneously reported and solicited collection methods. Drug Saf. 2005;28:1057–1063. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528110-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davenport ML, Crowe BJ, Travers SH, Rubin K, Ross JL, Fechner PY, Gunther DF, Liu C, Geffner ME, Thrailkill K, Huseman C, Zagar A, Quigley CA. Growth hormone treatment of early growth failure in toddlers with Turner syndrome: a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3406–3416. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zill N. Parental schooling and children's health. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:34–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Zielhuis GA, Rosenfeld RM. Otitis media. Lancet. 2004;363:465–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Margolis RH, Hunter LL. Acoustic immittance measurements. In: Roeser RJ, Valente M, Hosford-Dunn H, editors. Audiology. Diagnosis. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2000. pp. 381–425. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozza RJ, Bluestone CD, Kardatzke D, Bachman R. Towards the validation of aural acoustic immittance measures for diagnosis of middle ear effusion in children. Ear Hear. 1992;13:442–453. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nozza RJ, Bluestone CD, Kardatzke D, Bachman R. Identification of middle ear effusion by aural acoustic admittance and otoscopy. Ear Hear. 1994;15:310–323. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roush J, Bryant K, Mundy M, Zeisel S, Roberts J. Developmental changes in static admittance and tympanometric width in infants and toddlers. J Am Acad Audiol. 1995;6:334–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Chicchis AR, Todd NW, Nozza RJ. Developmental changes in aural acoustic admittance measurements. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanks JE, Stelmachowicz PG, Beauchaine KL, Schulte L. Equivalent ear canal volumes in pre- and post-tympanostomy tube insertion. J Speech Hear Res. 1992;35:936–941. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3504.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morimoto N, Tanaka T, Taiji H, Horikawa R, Naiki Y, Morimoto Y, Kawashiro N. Hearing loss in Turner syndrome. J Pediatr. 2006;149:697–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkiömäki MR, Kyrkanides S, Niinimaa A, Alvesalo L. The relationship of distinct craniofacial features between Turner syndrome females and their parents. Eur J Orthod. 2005;27:48–52. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjh086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bluestone CD, Klein JO. Otitis media, telectasis, and eustachian tube dysfunction. In: Bluestone CD, Stool SE, editors. Pediatric Otolaryngology. ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990. pp. 332–334. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrenäs M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Hanson C. Ear and hearing in relation to genotype and growth in Turner syndrome. Hear Res. 2000;144:21–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao E, Weiss B, Fukami M, Rump A, Niesler B, Mertz A, Muroya K, Binder G, Kirsch S, Winkelmann M, Nordsiek G, Heinrich U, Breuning MH, Ranke MB, Rosenthal A, Ogata T, Rappold GA. Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:54–63. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clement-Jones M, Schiller S, Rao E, Blaschke RJ, Zuniga A, Zeller R, Robson SC, Binder G, Glass I, Strachan T, Lindsay S, Rappold GA. The short stature homeobox gene SHOX is involved in skeletal abnormalities in Turner syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:695–702. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsen WJ. Development of the head and neck; in Human Embryology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. pp. 311–374. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostberg JE, Beckman A, Cadge B, Conway GS. Oestrogen deficiency and growth hormone treatment in childhood are not associated with hearing in adults with Turner syndrome. Horm Res. 2004;62:182–186. doi: 10.1159/000080888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hultcrantz M, Sylvén L, Borg E. Ear and hearing problems in 44 middle-aged women with Turner's syndrome. Hear Res. 1994;76:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamelin CE, Anglin G, Quigley CA, Deal CL. Genomic imprinting in Turner syndrome: effects on response to growth hormone treatment and on risk of sensorineural hearing loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3002–3010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roush J, Davenport ML, Carlson-Smith C. Early-onset sensorineural hearing loss in a child with Turner syndrome. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000;11:446–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fish JH, 3rd, Schwentner I, Schmutzhard J, Abraham I, Ciorba A, Martini A, Sergi C, Schrott-Fischer A, Glueckert R. Morphology studies of the human fetal cochlea in Turner syndrome. Ear Hear. 2009;30:143–146. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181906c30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Erum R, Mulier M, Carels C, Verbeke G, de Zegher F. Craniofacial growth in short children born small for gestational age: effect of growth hormone treatment. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1579–1586. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760091001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blum WF, Crowe BJ, Quigley CA, Jung H, Cao D, Ross JL, Braun L, Rappold G, SHOX Study Group Growth hormone is effective in treatment of short stature associated with short stature homeobox-containing gene deficiency: two-year results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:219–228. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paradise JL, Dollaghan CA, Campbell TF, Feldman HM, Bernard BS, Colborn DK, Rockette HE, Janosky JE, Pitcaim DL, Kurs-Lasky M, Sabo L, Smith CG. Otitis media and tympanostomy tube insertion during the first three years of life: developmental outcomes at the age of four years. Pediatrics. 2003;112:265–277. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts JE, Rosenfeld RM, Zeisel SA. Otitis media and speech and language: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e238–e248. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rovet J. Turner syndrome: a review of genetic and hormonal influences on neuropsychological functioning. Child Neuropsychol. 2004;10:262–279. doi: 10.1080/09297040490909297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]