Abstract

Admission to nursing home (NH) is considered a poor outcome for community-dwelling older adults. The objective of this study was to determine if depression increased risk of NH admission. Using the 2001–2003 National Hospital Discharge Survey datasets, the authors identified 28,172 community-dwelling older adults, 65 years and older, discharged alive with a primary discharge diagnosis of coronary artery disease. The objective of this study was to determine association between depression and subsequent nursing home admissions in these patients. Propensity scores for depression, calculated for each patient using multivariable logistic regression model, were used to match 686 depressed patients with 2,058 non-depressed patients who had similar propensity scores. Logistic regression analyses were used to determine the association between depression and NH admission. Patients had a mean (±SD) age of 77 (±8) years and 61% were women. Compared with 9% non-depressed patients, 13% of depressed patients were admitted to nursing homes (relative risk =1.42; 95% confidence interval =1.12–1.78). When adjusted for various demographic, clinical, and care-related covariates, the association became somewhat stronger (adjusted relative risk =1.55; 95% confidence interval =1.21–1.99). In ambulatory older adults hospitalized with CAD, a secondary diagnosis of depression was associated with a significant increased risk of NH admission.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is common, and the prevalence and incidence increase with age. Older adults suffer disproportionately from CAD, with over 80% CAD-related deaths occurring in patients 65 years and older.1 Depression is also common among older adults, and is associated with poor outcomes.2 Depression is particularly common among patients with CAD, and is associated with poor outcomes in these patients.3-9

Admission to a nursing home (NH) is often considered a poor outcome for community-dwelling older adults, which is associated with loss independent living, poor quality of care and poor prognosis.10, 11, 12 Hospitalization due to chronic disease or its acute exacerbation is also considered an adverse outcome, and is associated with increased risk of NH admission for community-dwelling older adults.13-15 However, it is unknown to what extent depression is associated with subsequent NH admission for ambulatory older adults hospitalized with CAD. The objective of the current study was to determine the effect of depression on NH admission in older adults hospitalized for CAD.

METHODS

Data Source

The National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) consists of a continuous sample of hospital discharge records abstracted annually from medical records of patients treated at nonfederal short-stay hospitals in all fifty states and the District of Columbia.16 The NHDS datasets are available to the public through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/hdasd/nhds.htm. Inclusion eligibility is restricted to hospitals having six or more beds and where the average length of stay for all patients is less than thirty days. The sample is updated periodically to reflect changes in eligibility. Medical diagnoses and surgical procedures contained in the NHDS are coded according to the International Classification of Disease, 9th revision, Clinical modification (ICD -9-CM) codes. The NHDS adopts a complex, stratified, multistage probability design to ensure a representative national sampling. Variables in the NHDS dataset include data on age, gender, race, marital status, primary discharge diagnosis and six secondary discharge diagnoses, hospital bed size, hospital geographic location, hospital ownership, type of hospital admission, primary and secondary source of payment, discharge month and length of stay.17

Patients

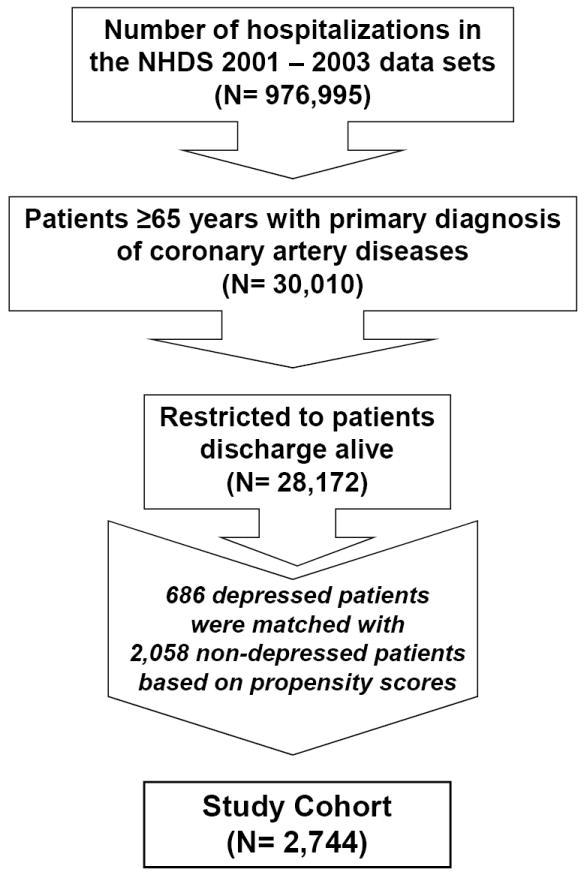

For the purpose of this analysis, we merged the 2001, 2002 and 2003 NHDS datasets, and restricted our analysis to patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of CAD. The 2001 – 2003 NHDS datasets included 976,995 sampled hospital discharges. Patients younger than 65 years, those with pre-admission residence in NH, and those who died during their hospital stay were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of the study cohort

Primary Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease

Patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of CAD were identified by the ICD-9-CM codes 410, 411, 412, 413 and 414. Of the 976,995 patients in the 2001 -2003 NHDS datasets, 30,010 were aged ≥65 years and discharged with a primary discharge diagnosis of CAD (Figure 1). Of these, 28,172 were discharged alive from the hospital. It is important to note that the NHDS is based on coded hospital discharge records and collected information does not allow identification of individual patients. There is a possibility that patients with multiple hospitalizations were captured more than once but these duplications are likely to be random. As such, we treated each discharge as representing a unique patient in our analyses.

Secondary Diagnosis of Depression

Out of the 28,172 individuals with CAD, a total of 686 patients were identified as having a secondary diagnosis of depression at time of discharge. These individuals were identified using ICD-9-CM codes 296 (affective psychoses, includes 296.0 – 296.9), 311 (depressive disorder, not elsewhere classified), and 300.4 (neurotic depression).

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of interest was NH admission as ascertained at the time of hospital discharge, and identified from the “discharge status” variable in the datasets.

Other Secondary Diagnoses

The NHDS collected data on up to six secondary discharge diagnoses for each patient. Using this record, a list of co-morbid conditions based on ICD-9 codes was assembled. The list included heart failure (428), dysrhythmias (427), hypertension (401-405), diabetes mellitus (250), hypothyroidism (244), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (491-492, 496), pneumonia (480-487), syncope (780.2), acute renal failure (584), iron deficiency anemia (280), urinary incontinence (788), urinary tract infection (599), and dementia (094, 290, 291, 292, 294 and 331). These other secondary diagnoses were chosen due to their known associations with either the predictor variable, a secondary diagnosis of depression, or the outcome variable, admission to a NH.

Statistical Analysis

After descriptive analysis of the baseline characteristics for the pre-match cohort of patients with and without depression (Table 1, left hand panel), propensity scores were calculated to control for the imbalance in baseline covariates between patients. Matching by propensity score often balances all measured covariates and is superior to matching by individual covariates such as age, sex, race, etc. The propensity score is the conditional probability of receiving a particular exposure or treatment given a vector of covariates,18-20 and has been used in the literature to control for selection bias between two treatment groups.21-23 More recently, the technique has been used to control for the imbalance in baseline covariates between two groups of patients with and without a certain co-morbid condition.24 One of the key limitations of propensity score technique is, however, that unlike randomization, it cannot balance unmeasured covariates. However, as patients cannot be randomized to develop depression, that is less of a concern for the current analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline patients characteristics by the depression pre and post-matched with propensity scores

| Pre-Match | Post-Match | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression | Depression | P value | No Depression | Depression | P value | |

| N = 27,486 | N = 686 | N = 2058 | N = 686 | |||

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 76 (± 7) | 77 (±8) | 0.001 | 77 (±8) | 77 (±8) | |

| Female | 13024 (47%) | 420 (61%) | <0.0001 | 1248 (61%) | 420 (61%) | 0.786 |

| African American | 1967 (7%) | 31 (5%) | 0.008 | 88 (4%) | 31 (4.5%) | 0.787 |

| Married | 4992 (18%) | 118 (17%) | 0.519 | 350 (17%) | 118 (17%) | 0.907 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 7095 (26%) | 164 (24%) | 0.259 | 497 (24%) | 164 (24%) | 0.897 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmia | 6686 (24%) | 102 (15%) | <0.0001 | 307 (15%) | 102 (15%) | 0.975 |

| Heart failure | 6516 (24%) | 147 (21%) | 0.165 | 476 (23%) | 147 (21%) | 0.357 |

| Hypertension | 15472 (56 %) | 393 (57%) | 0.603 | 1234 (60%) | 393 (57%) | 0.217 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1684 (6%) | 89 (13%) | <0.0001 | 262 (13%) | 89 (13%) | 0.869 |

| Incontinence | 261 (1%) | 14 (2%) | 0.004 | 46 (2%) | 14 (2%) | 0.763 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1511 (6%) | 25 (4%) | 0.035 | 77 (4%) | 25 (4%) | 0.907 |

| Acute renal failure | 913 (3.3%) | 3 (0.4%) | <0.0001 | 3 (.1%) | 3 (.4%) | 0.157 |

| Syncope | 432 (2%) | 12 (2%) | 0.712 | 31 (2%) | 12 (2%) | 0.657 |

| Dementia | 846 (3%) | 60 (9%) | <0.0001 | 169 (8 %) | 60 (97%) | 0.661 |

| Pneumonia | 975 (4%) | 11 (2%) | 0.006 | 29 (1%) | 11 (2%) | 0.713 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4476 (16%) | 111 (16%) | 0.942 | 354 (17%) | 111 (16%) | 0.537 |

| Iron deficient anemia | 443 (2%) | 6 (1%) | 0.128 | 13 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 0.506 |

| Hospitals (beds) | ||||||

| Small (6-199) | 8197 (30%) | 294 (43%) | <0.0001 | 873 (42%) | 294 (43%) | 0.960 |

| Medium (200-499) | 15213 (55%) | 303 (44%) | 910 (44%) | 303 (44%) | ||

| Large (≥500) | 4076 (15%) | 89 (130%) | 275 (13%) | 89 (13%) | ||

| Hospitals by geographic region | ||||||

| Northeast | 6458 (24%) | 180 (26%) | 0.030 | 519 (25%) | 180 (26%) | 0.798 |

| Midwest | 9889 (36%) | 242 (35%) | 750 (36%) | 242 (35%) | ||

| South | 7857 (29%) | 205 (30%) | 594 (29%) | 205 (30%) | ||

| West | 3282 (12%) | 59 (9%) | 195 (10%) | 59 (9%) | ||

| Hospitals by ownership | ||||||

| For profit | 3248 (12%) | 74 (11%) | 0.409 | 228 (11%) | 74 (11%) | 0.833 |

| Non-profit | 24238 (88%) | 612 (89%) | 1830 (89%) | 612 (89%) | ||

| Type of admission | ||||||

| Emergency | 11448 (42%) | 328 (48%) | 0.001 | 1017 (49%) | 328 (48%) | 0.467 |

| Non-emergency | 16038 (58%) | 358 (52%) | 1041 (51%) | 358 (52%) | ||

| Source of payment | ||||||

| Medicare | 23968 (87%) | 624 (91%) | 0.003 | 1876 (91%) | 624 (91%) | 0.877 |

| Medicaid | 1874 (7%) | 56 (8%) | 0.168 | 208 (10%) | 56 (8%) | 0.135 |

| Private | 12077 (44%) | 313 (46%) | 0.379 | 946 (46%) | 313 (46%) | 0.877 |

| Length of stay | ||||||

| ≤ 4 days | 17520 (64%) | 456 (67%) | 0.142 | 1435 (70%) | 456 (67%) | 0.111 |

| > 4 days | 9966 (36%) | 230 (34%) | 623 (30%) | 230 (34%) | ||

| Discharge in July or August | 4595 (17%) | 128 (19%) | 0.179 | 386 (19%) | 128 (19%) | 0.955 |

We calculated propensity scores for depression, using a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model, with depression as the dependent variable, and all measured baseline characteristics as covariates. The covariates used in the model are presented in Table 1. The resulting propensity score for depression was used to match patients who had a secondary diagnosis of depression with up to three patients without the secondary diagnosis who had similar propensity scores. An SPSS macro was used to randomly match patients.25 Overall, 686 patients with depression were matched with 2058 patients without depression.

Baseline characteristics between the patients with and without depression in post-match cohort were compared, and absolute standardized differences on key covariates were estimated.26, 27 Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess NH admission for depressed patients compared with those not depressed. Covariates in the multivariable model were the same as those used in the model for propensity score. The effect of other covariates on NH admission was also examined using the same model, with age and length of stay as categorical variables. Odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were then converted into relative risks.28 The effects of depression on subgroups of patients based on age, sex, race, marital status, heart failure, diabetes, dementia, and hypothyroidism were examined. All tests were based on a 2-sided p value and p values of <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were done using SPSS 13.2 for Windows.29

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

After propensity score matching, the final cohort (N=2,744) had a mean (±SD) age of 77 (±8) years, 1,668 (61%) were female, and 119 (4%) were reported as African Americans. Table 1 compares the baseline characteristics between patients with and without a secondary diagnosis of depression, before and after propensity score matching. Before matching, depressed patients were more likely to be female and have hypothyroidism, dementia and incontinence. Depressed patients were also less likely to be African Americans and have UTI, cardiac dysrhythmias, pneumonia, and acute renal failure. After matching, there was no significant difference in terms of any baseline covariates between the two groups (Table 1).

Depression and Nursing Home Admission

Compared with 9% of ambulatory older adults hospitalized with CAD who also had no secondary diagnosis of depression, 13% of those with a secondary diagnosis of depression were admitted to NH (relative risk = 1.42; 95% confidence interval = 1.12 – 1.78) (Table 2). When adjusted for various demographic, clinical, and care-related covariates, the association became stronger (adjusted relative risk = 1.55; 95% confidence interval = 1.21 – 1.99). Additional adjustment for propensity score did not alter this association (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR), relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for admission into nursing home among propensity score matched older adults discharged with a primary discharge diagnosis of coronary artery disease by depression

| No Depression | Depression | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 2058 | 686 |

| Admitted to nursing home | 191 | 90 |

| Absolute risk | 9% | 13% |

| Absolute risk difference | Reference | 4% |

| (Pearson Chi-square p 0.004) | ||

| OR, unadjusted (95% CI); p value | 1 | 1.48 (1.13 – 1.93); 0.004 |

| RR*, unadjusted (95% CI) | 1 | 1.42 (1.12 – 1.78) |

| OR, adjusted for covariates** (95% CI); p value | 1 | 1.64 (1.23 – 2.20); 0.001 |

| RR*, adjusted for covariates** (95% CI) | 1 | 1.55 (1.21 – 1.99) |

| OR, adjusted for covariates** and propensity scores (95% CI); p value | 1 | 1.64 (1.23 – 2.20); 0.001 |

| RR*, adjusted for covariates** and propensity scores (95% CI) | 1 | 1.55 (1.21 – 1.99) |

Converted from corresponding OR (Ref = 28)

Covariates used are the same used in the propensity score model

Other Predictors of Nursing Home Admission

Nursing home admission was greater among individuals aged 80 and older, while less likely among married individuals (Table 3). A secondary diagnosis of heart failure, urinary tract infection, urinary incontinence, and dementia as well as a length of hospital stay 4 or more days were associated with higher odds of NH admission. Patients who were hospitalized in the South and admitted to hospitals with bed size 500 or more had lower odds of being discharged to a NH.

Table 3.

Association between the covariates with admission into long-term care facilities

| Unadjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥80 years | 3.29 (2.55 – 4.24) | <0.001 | 2.42 (1.83 – 3.21) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1.29 (0.99 – 1.68) | 0.05 | 1.02 (0.76 – 1.36) | 0.91 |

| African American | 0.98 (0.53 – 1.81) | 0.95 | 1.13 (0.59 – 2.18) | 0.71 |

| Married | 0.44 (0.29 – 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.38 – 0.96) | 0.03 |

| Heart failure | 2.71 (2.09 – 3.51) | <0.001 | 1.81 (1.37 – 2.41) | <0.001 |

| Urinary incontinence | 3.03 (1.66 – 5.51) | <0.001 | 2.25 (1.16 – 4.36) | 0.02 |

| Urinary tract infection | 3.20 (2.01 – 5.09) | <0.001 | 1.85 (1.11 – 3.07) | 0.02 |

| Dementia | 4.21 (3.06 – 5.81) | <0.001 | 3.06 (2.15– 4.36) | <0.001 |

| Hospitals in the South | 0.66 (0.49 – 0.89) | 0.006 | 0.71 (0.51 – 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Hospital bed >500 | 0.47 (0.29 – 0.75) | 0.002 | 0.45 (0.28 – 0.74) | 0.002 |

| Admission from emergency room | 0.97 (0.76 – 1.24) | 0.83 | 0.73 (0.56 – 0.96) | 0.03 |

| Medicare insurance | 1.39 (0.95 - 2.02) | 0.09 | 1.91 (1.02– 3.58) | 0.04 |

| Length of stay =>4 days | 4.06 (3.14 – 5.24) | <0.001 | 3.43 (2.61 – 4.52 | <0.001 |

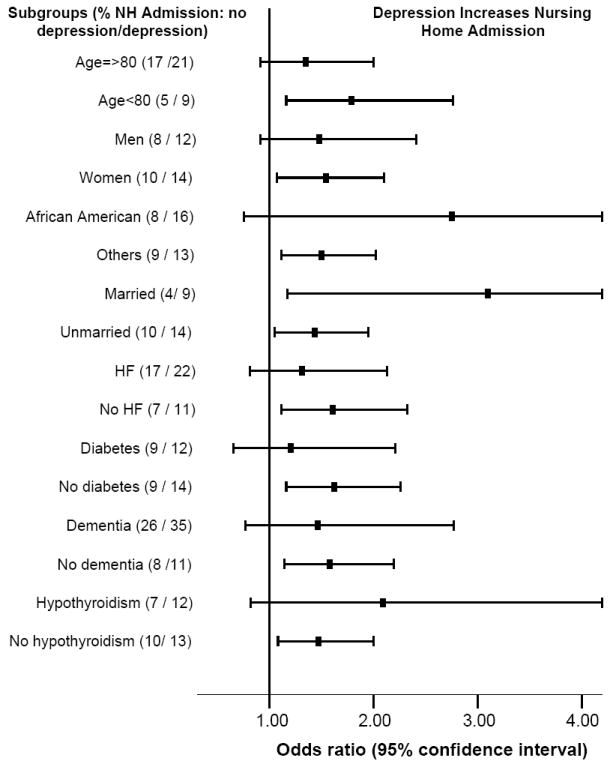

Results of the Subgroup Analysis

The association between depression and NH admission was observed in almost all subgroups of patients (Figure 3). Patients with a secondary diagnosis of dementia had the highest rate of admission to NH after hospital discharge: 35% and 26% respectively for patients with and without a secondary diagnosis of depression. There was no significant interaction observed between NH admission and included covariates.

DISCUSSION

Our study found that in a wide spectrum of ambulatory older adults hospitalized with CAD, the presence of a secondary diagnosis of depression or heart failure was significantly associated with NH admission. We also noted that traditional risk factors such as older age, unmarried marital status, presence of a secondary diagnosis of dementia, or urinary incontinence, were also associated with NH admission in these patients. These findings are important as NH admission is a marker of loss of independent community living and poor prognosis, and depression is common, and an identifiable and treatable condition.

Possible mechanistic explanations

Little is known about the specific physiologic mechanisms through which depression adversely affects hospital discharge disposition for these individuals. Increased depression-associated mortality in patients with CAD has been linked to increased platelet aggregation, greater autonomic dysfunction, immunological and hematological abnormalities, and behavioral and life style factors such as poor self-care and non-compliance.30-34 It is possible that CAD patients who are also depressed were sicker and had more severe CAD and thus poor outcomes such as NH admission. This is supported by our observation that CAD patients who also had a secondary diagnosis of heart failure were at increased risk of NH admission. However, as can be seen from Table 1, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with or without depression who also had heart failure as a secondary diagnosis. Therefore, it is unlikely that the effect of depression on NH admission observed in our study was mediated by heart failure. It is also possible that depressed CAD patients were more functionally impaired than those without depression. However, we had data on major disease conditions that are markers for functional impairment in old age, such as dementia and heart failure, and there were no baseline imbalance in those between groups. It is also possible that depressed patients lost physical function at a faster rate, or were unable to recover from the functional loss in due course, and thus were more likely to be admitted to NH.

Comparison with relevant findings from the literature

Most studies involving depression and CAD involve relatively younger adults.3, 5, 7 and none of these studies examined the effect of depression on NH admission. Our study is the first to demonstrate that the adverse effects of depression in patients with CAD also include loss of independent living in the community via admission to a NH. We noted that in addition to traditional predictors of NH admission, a secondary diagnosis of heart failure was also associated with a higher risk. This is an interesting observation and requires further study of the possible link between heart failure, CAD, and NH admission. It is not clear as to why patients hospitalized in the South and in large hospitals were less likely to be admitted to NH.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. It is based on a nationally representative sample of older adults hospitalized with CAD. Our use of propensity score matching allowed us to achieve a reasonable balance in baseline covariates between patients with and without depression. Exclusion of patients with NH residency prior to hospitalization allowed us to examine the effect of depression on NH admission among patients who were community-dwelling prior to hospital admission. Current NH residency is a strong predictor of NH re-admission after hospital discharge.15, 35, 36 Finally, we expressed our results in risk ratio, as opposed to odds ratio, thereby avoiding possible inflation of the association and making it easier to interpret.28, 37

Limitations of our study include use of secondary diagnosis of depression which is often coded for billing purposes. Depression in older adults is often atypical, presenting with somatic symptoms, and difficult to diagnose.38 It is possible that assessment of depression was not a priority in an acute care setting, which in part explains the lower prevalence of depression (Table 1) observed in our study compared to other studies.39 It is possible that those listed as having a secondary diagnosis of depression were individuals with severe depression, or those with anti-depressant medication listed as a discharge medication. It is also reasonably possible that many depressed patients were classified as not having a secondary diagnosis of depression, and some non-depressed patients were classified as having depression. This misclassification was most likely independent of the occurrence of the outcome (NH admission) and therefore random. Random misclassification increases the similarity between the two groups, thus resulting in dilution or underestimation of the true relative risk or odds ratio.40 Finally, limited ability to adjust for comorbid conditions and their severity in administrative datasets and the inability of propensity scores technique to adjust for unmeasured covariates must be acknowledged.

Conclusions

A secondary diagnosis of depression was associated with increased risk of admission to NH among ambulatory older adults hospitalized with CAD. Future prospective cohort studies should be conducted to examine the effect of depression on NH admission and other outcomes important to older adults such as physical function and quality of life, and if therapy with anti-depressants would reduce these adverse effects.

Figure 2.

Effect of depression on nursing home admission among community dwelling older adults hospitalized with coronary artery diseases (CAD)

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ahmed is supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants from the National Institute on Aging (1-K23-AG19211-04) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1-R01-HL085561-01 and P50-HL077100).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

AA conceived the study hypothesis and design, and wrote the paper in collaboration with CML and NA. CML and NA performed the statistical analysis under supervision of AA. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data, participated in critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the article. All had full access to the data.

Location of work: University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA

References

- 1.American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2005 update. Dallas, Texas: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The National Institute of Mental Health. Older Adults: Depression and Suicide Facts. A brief overview of the statistics on depression and suicide in older adults, with information on depression treatments and suicide prevention. [May 4, 2004]; http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/elderlydepsuicide.cfm#4.

- 3.Barefoot JC, Helms MJ, Mark DB, et al. Depression and long-term mortality risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Sep 15;78(6):613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford DE, Mead LA, Chang PP, Cooper-Patrick L, Wang NY, Klag MJ. Depression is a risk factor for coronary artery disease in men: the precursors study. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Jul 13;158(13):1422–1426. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.13.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng D, Macera CA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Davis D, Scott WK. Major depression and all-cause mortality among white adults in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 1997 Apr;7(3):213–218. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zellweger MJ, Osterwalder RH, Langewitz W, Pfisterer ME. Coronary artery disease and depression. Eur Heart J. 2004 Jan;25(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wassertheil-Smoller S, Shumaker S, Ockene J, et al. Depression and cardiovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Arch Intern Med. 2004 Feb 9;164(3):289–298. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan MD, Newton K, Hecht J, Russo JE, Spertus JA. Depression and health status in elderly patients with heart failure: a 6-month prospective study in primary care. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2004 Sep-Oct;13(5):252–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1076-7460.2004.03072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauerbach JA, Bush DE, Thombs BD, McCann UD, Fogel J, Ziegelstein RC. Depression following acute myocardial infarction: a prospective relationship with ongoing health and function. Psychosomatics. 2005 Jul-Aug;46(4):355–361. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couture M, Lariviere N, Lefrancois R. Psychological distress in older adults with low functional independence: a multidimensional perspective. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005 Jul-Aug;41(1):101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gambassi G, Lapane KL, Sgadari A, et al. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and digoxin on health outcomes of very old patients with heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000 Jan 10;160(1):53–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed A, Weaver M, Allman RM, DeLong JF, Aronow WS. The quality of care of nursing home residents hospitalized with heart failure. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002 doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50512.x. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glazebrook K, Rockwood K. A case control study of the risk for institutionalization of elderly people in Nova Scotia. Canadian Journal of Aging. 1994;13(1):104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudberg MA, Sager MA, Zhang J. Risk factors for nursing home use after hospitalization for medical illness. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(5):M189–194. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.5.m189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed A, Allman RM, DeLong JF. Predictors of nursing home admission for older adults hospitalized with heart failure. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003 Mar-Apr;36(2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(02)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dennison C, Pokras R. Design and operation of the National Hospital Discharge Survey: 1988 redesign. [July 7, 2004];Vital Health Stat. 2000 1(39) Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_039.pdf. [PubMed]

- 17.Statistics NCfH. [12/16/2005, 2005];National Hospital Discharge Survey Description. 2005 February 2; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/hdasd/nhdsdes.htm.

- 18.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Asso. 1984;79:516–524. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Oct 15;127(8 Pt 2):757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB. Using propensity score to help design observational studies: Application to the tobacco litigation. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2001;2:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronow HD, Topol EJ, Roe MT, et al. Effect of lipid-lowering therapy on early mortality after acute coronary syndromes: an observational study. Lancet. 2001 Apr 7;357(9262):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newby LK, Kristinsson A, Bhapkar MV, et al. Early statin initiation and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002 Jun 19;287(23):3087–3095. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brener SJ, Lytle BW, Casserly IP, Schneider JP, Topol EJ, Lauer MS. Propensity analysis of long-term survival after surgical or percutaneous revascularization in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease and high-risk features. Circulation. 2004 May 18;109(19):2290–2295. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126826.58526.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubal C, Srinivasan AK, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Chalmers JA. Effect of risk-adjusted diabetes on mortality and morbidity after coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005 May;79(5):1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levesque R. Macro. In: Levesque R, editor. SPSS® Programming and Data Management, 2nd Edition. A Guide for SPSS® and SAS® Users. 2. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; [June 4, 2005]. 2005. Available online at: http://www.spss.com/spss/data_management_book.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998 Oct 15;17(19):2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, et al. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Apr;54(4):387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998 Nov 18;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SPSS 13.2 for Windows [computer program]. Version 12.02. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musselman DL, Tomer A, Manatunga AK, et al. Exaggerated platelet reactivity in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996 Oct;153(10):1313–1317. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Eisen SA, Rich MW, Jaffe AS. Major depression and medication adherence in elderly patients with coronary artery disease. Health Psychol. 1995 Jan;14(1):88–90. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strike PC, Steptoe A. Depression, stress, and the heart. Heart. 2002 Nov;88(5):441–443. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.5.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruo B, Rumsfeld JS, Hlatky MA, Liu H, Browner WS, Whooley MA. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life: the Heart and Soul Study. JAMA. 2003 Jul 9;290(2):215–221. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joynt KE, Whellan DJ, O’Connor CM. Why is depression bad for the failing heart? A review of the mechanistic relationship between depression and heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004 Jun;10(3):258–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachtel TJ, Fulton JP, Goldfarg J. Early prediction of discharge disposition after hospitalization. Gerontologist. 1987 Feb;27(1):98–103. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narain P, Rubenstein LZ, Wieland GD, et al. Predictors of immediate and 6-month outcomes in hospitalized elderly patients. The importance of functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(9):775–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 May 15;157(10):940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freedland KE, Lustman PJ, Carney RM, Hong BA. Underdiagnosis of depression in patients with coronary artery disease: the role of nonspecific symptoms. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22(3):221–229. doi: 10.2190/YF10-H39R-NY6M-MT1G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang W, Glassman A, Krishnan R, O’Connor CM, Califf RM. Depression and ischemic heart disease: what have we learned so far and what must we do in the future? Am Heart J. 2005 Jul;150(1):54–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Cohort Studies. In: Mayrent SL, editor. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston/Toronto: Little, Brown, and Company; 1987. pp. 168–170. [Google Scholar]