Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the influence of amplicons size and cell type on allele dropout and amplification failures in single-cell based molecular diagnosis.

Methods

730 single lymphocytes and amniotic cells were collected from known heterozygotes individuals to one of the common Ashkenazi Jewish mutations: 1278+TATC and IVS12+1G>C which cause Tay Sachs Disease, IVS20+6T and 854A>C which underlie Familial Dysautonomia and Canavan Disease. DNA was extracted and analyzed by our routine methods.

Results

Reduced rates of allele dropout and amplification failure were found when smaller amplification product were designed and in amniotic cultured cells compared to peripheral lymphocytes. Cultured lymphocytes, induced to divide, demonstrated significantly less allele dropout than non induced lymphocytes suggesting the role of division potential on amplification efficiency.

Conclusion

Single cell based diagnosis should be designed for each mutation. Minimal sized amplicons and cell having division potential should be preferred, as well as sensitive techniques to detect preferential amplification.

Keywords: Single cell, Allele drop-out, Preimplantation genetic diagnosis, PCR-failure

Introduction

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) can sometimes be used as an alternative to prenatal diagnosis options, amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling. This technique involves in-vitro fertilization (IVF), biopsy of a cell or two from the developing embryos and single-cell genetic diagnosis leading to transfer of unaffected embryo [1]. Single cells have been analyzed for a range of disorders by cytogenetic and molecular methods [2, 3]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based PGD has been successfully assessed for sex determination in cases of X-linked disorders, monogenic autosomal recessive and dominant disorders [4–6]. Different diagnostic strategies have been reported in recent years; single versus two blastomeres biopsy, polar body diagnosis, identification of specific mutations, linkage with polymorphic markers or a selection of combinations [7].

Single cell molecular analysis confronts major technical problems stemming from the minute initial amount of DNA and the many PCR cycles required for diagnosis. Amplification failure (AF), allele dropout (ADO) and unrelated DNA contamination are the most challenging [7]. AF was reported to occur in 5%–10% of single cells subjected to PCR, frequently due to technicalities such as nucleus disintegration, unsuccessful transfer to the PCR tube or failure of cell lysis [8, 9]. ADO which is the failure to amplify one of the two alleles is considered to strike randomly in a given locus and was reported to occur in 0%–40% of single cells based diagnoses [8–11]. ADO might potentially lead to the transfer of an affected embryo and consequently to misdiagnosis. Several hypotheses as to the origin of ADO and techniques to minimize it have been proposed [10–14].

The present study was designed to further evaluate factors which might have an impact on AF and ADO rates in PCR-based single cell diagnosis. Quantification of ADO and AF was carried out on 730 single lymphocytes and amniocytes isolated from carriers of four common mutations among the Jewish Ashkenazi population.

Materials and methods

Patients and cells Blood samples were obtained from individuals who participated in the population screening program for carriers’ detection. Molecular tests for: Tay Sachs, Canavan and Familial Dysautonomia were offered to Jews of Ashkenazi origin. Each patient who was diagnosed as a carrier was routinely reanalyzed in a second sample. Amniotic cultured cells (amniocytes) were obtained from the cytogenetic laboratory after the completion of the molecular diagnosis. All single cells were isolated from sample of Jewish Ashkenazi individuals who had been already diagnosed as heterozygotes to a mutation in the genes HEXA, IKBKAP or ASPA (detailed in Table 1). Each participant was consented to allow the use of his samples following the completion of all indicated clinical diagnostic tests. The study was approved by the institutional Internal Review Board.

Table 1.

Study protocols

| Protocol | Gene and mutation | Primer | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HEXA (Tay Sachs Disease) Mut: +1278 TATC | OF | CCA GGA ATC TCC TCA GCT TTG TGT |

| OR | AGC CTC CTT TGG TTA GCA AGG | ||

| IFc | GTG TGG CGA GAG GAT ATT CCA GT | ||

| IR | TTC AAA TGC CAG GGG TTC CAC TA | ||

| 2 | HEXA (Tay Sachs disease) Mut: IVS12+1G>C | OF | AGT TAC CCC ACC ATC ACC AGA CTG |

| OR + IR | TCC TGC TCT CAG GCC CAA CCC TC | ||

| IFd | AGC AGA AGG CTC TGG TGA TTG GT | ||

| 3a | HEXA (Tay Sachs disease) Mut: Compoundb | OF | CCA GGA ATC TCC TCA GCT TTG TGT |

| OR | TCC TGC TCT CAG GCC CAA CCC TC | ||

| 4a | ASPA (Canavan Disease) Mut: 854A>C | OF + IFc | CTCTTGATGGGAAGACGATC |

| OR | TGAATAAGGCACAACCCTACTCTTA | ||

| IR | ACACCGTGTAAGATGTAAGC | ||

| 5a | IKBKAP (Familial Dysautonomia) Mut: IVS20+6T>C | OF | CTGATTTTAGAGAGTTGTGGTA |

| OR + IR | ATCTCCACTACAAAATACTGC | ||

| IFc | ATGCCAAGGGGAAACTTAGAAG |

aHeminested protocols; bCompound heterozygote for Tay Sachs disease: +1278 TATC and IVS12+1G>C. Inner PCR primers were identical to inner primers of protocol 1 and 2

OF outer forward primers, OR outer reverse primer, IF inner forward primer, IR inner reverse primer. When fluorescence PCR is used than: cTagged with FAM or dTagged with Cy5

Preparation of lymphocytes and amniocytes suspensions 0.5–1 ml of peripheral blood (in EDTA) was diluted in 5 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Gibco USA) and 3 ml of isoprep for human lymphocyte isolation (density of 1.077 ± 0.001 gr/ml , Robbins Scientific, USA) were gently added to the bottom of the tube. The tubes were centrifuged at 1,100 g for 10 min in room temperature [15] and the middle ring was collected, suspended in 4 ml of saline and centrifuged at 670 g for 10 min in room temperature. The final pellet was re-suspended in 11 ml saline. The above procedure is routinely used in the hematology laboratory and provides suspensions containing above 95% of mononuclear cells with a very high proportion of lymphocytes (no further cell type differentiation was made).Cells from non confluent cultures of amniocytes on their 1st–2nd passage were collected, centrifuged for 10 min at 670 g in room temperature and the pellets re-suspended in 11 ml of saline.

Isolation of single cells The final suspensions were thoroughly vortexed in order to break up cell aggregates and then kept intact in room temperature for 1 h. The cells descended and formed small sediments while the debris resided in the supernatant. The pellets were re-diluted in 11 ml of saline and one drop was placed in a Petri dish for aspiration by a capillary (0.16 mm, Drummond, Bioline, Israel) using a micromanipulator (TransferMan NK®, Eppendorf, Germany) and Zeiss microscope (Axiovert, Germany).Further dilutions were carried out if needed until single separated cells could be easily seen.

Induction of lymphocytes About 0.3 ml of whole heparinized blood were suspended in 5 ml of medium (kariotyping medium, Biological Industries, Israel). 0.1 ml of 2% phytohemaglutinin (Biological Industries, Israel) was added and the suspension was incubated for 72 h in 37°C. Single cell isolation was carried out as described above.

Cell lysis Each single cell was transferred into 0.2 ml sterile tube (DNAse/ RNAse free PCR tubes, ABgene, UK) containing 5 μl alkaline lysis buffer (200 mM KOH with 50 mM dithiothreitol, final concentrations) and kept frozen in −20°C until further use. The samples were heated for 15 min in 65°C just prior to DNA amplification followed by addition of 5 μl neutralizing buffer (1M Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 300 mM KCl) [16].

Primer design and nested PCR protocols All protocols and nested primer sets for the diagnosis of the five mutations are detailed in Table 1. The reaction mixtures were prepared in a specific “single-cell” dedicated room which is clean of PCR products and equipped with a Cleanspot (Coy Laboratory, USA), sterile disposables and reagents which were kept inside once brought in. Amplification was carried out by either Taq MBI Polymerase (Fermentas, Lithuania) (protocols 1, 3, 4, Table 1) or Taq gold (Applied Biosystems, UK) (protocols 2 and 5, Table 1) both at a final concentration of 0.03 u/μl. The outer PCR mixture consisted of 0.25 μM of each primer (Metabion, Germany), 0.2 mM dNTPs (Applied Biosystems, UK), 0.1 M Tris HCl pH = 8.3 (Fisher, USA), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Fisher, USA), 10% (w/v) gelatin (Sigma) and with distilled deionized water was added to a total volume of 50 or 100 μL (PCR grade Fisher, USA). The reaction with Taq gold was with distilled deionized water initialized with a hot start of 15 min in 95°C followed by 15 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 45 s, annealing at 50°C for 45 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min, and 20 additional cycles of annealing at 52°C, 54°C and 55°C (protocols 1+3, protocols 4 and 2 respectively) for 45 s, extension at 72°C for 1 min and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The reactions steps with Taq MBI enzyme were identical to the above except for an initial denaturation of 5 min. All second (inner) PCR rounds were carried out with 0.03 u/μl Taq—MBI, 2 mM of MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP mixture, 10 pmols of each inner primer, 2 μl of first PCR products and water to a final volume of 50 μl. Second PCR steps started with 5 min denaturation in 95°C followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, annealing temperature of 54–59°C for 45 s, 72°C for 1 min and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min.

Mutations detection

heterozygote diagnosis was achieved by either heteroduplex formation in 3% agarose gel [17] or by fragment analysis using 3100 Avant, ABI Genetic Analyzer (Perkin Elmer, UK).The primer used for the fragment analysis was tagged with FAM fluorescent dyes (Metabion, Germany).

the mutation IVS12+1G-C generates a novel recognition site to DdeI which could be identified by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis [18] or by electrophoresis on automatic laser fluorescent express system (ALF, Pharmacia, Sweden ) using Cy5 label primers (Pharmacia, Sweden).

mutation detection according to protocols 1 and 2.

the mutations 854A-C and IVS20+6T induce new restriction sites for the enzymes; EagI and HinpI respectively [19, 20]. The mutations identification following the restriction analysis was carried out by electrophoresis on agarose gel 3% and the ABI Genetic Analyzer. All restriction assays were performed according to the manufacturer instructions with the buffers supplied.

In each experiment, blanks (no DNA samples) were analyzed to confirm that no contamination by external DNA occurred. A known positive control of a heterozygote was also used in each run and in some cases a sample of a homozygote was added to confirm the complete enzymatic digest and correct electrophoresis conditions. Occasionally, in cases of suspected ADO the restriction analysis was repeated (enzyme was added again to the reaction tube) to ensure the ADO result and complete enzymatic digest, Fig. 1. In order to differentiate between quantitative and qualitative failures, the inner PCR was repeated with one or two additional concentrations of the outer PCR products in all cases of AF or ADO.

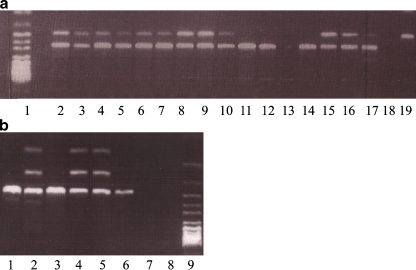

Fig. 1.

Diagnosis by PCR and restriction digest in single cells. a. Detection of the mutation IVS20+6T→C in the IKBCAP gene. Lane 1—DNA ladder, 50–100 bp. Lanes 2–9—Single culture cells of heterozygote embryos. Lane 10—A single lymphocyte of a heterozygote individual. Lane 11—A single lymphocyte of a heterozygote individual that presents ADO of the mutant allele. Lane 12—A single lymphocyte of a non carrier. Lane 13—A single lymphocyte showing PCR failure. Lane 14—Normal control DNA, 1 ng/μl. Lanes 15—Control of heterozygote DNA, 1 ng/μl. Lanes 16–17—Controls of heterozygote DNA, 100 pg/μl. Lane 18—Blank sample (no DNA). Lane 19—Control of mutant homozygote DNA 1 ng/μl. b. Detection of the mutation 854A→C in the ASPA gene. Lane 1—Control of normal DNA 100 pg/μl. Lane 2—Control of Heterozygote DNA 100 pg/μl. Lane 3—A single amniotic cell, homozygote norml. Lanes 4–5—Single amniotic cells of heterozygote embryos. Lane 6—A single lymphocyte of a heterozygote individual showing ADO of the Mutant. Lane 7—Blank sample (no DNA). Lane 9—DNA ladder, 50–100 bp

Statistical analysis Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test were used for statistical analysis of categorical data as appropriate. Statistical significant difference was accepted for p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Four hundreds ninety two single lymphocytes and fibroblasts of heterozygous individuals to one of the two mutations in the HEXA gene were analyzed according to protocols 1, 2 or 3. There was a clear trend of increasing AF and ADO rates in the protocols which result in larger outer PCR fragments (Table 2). PCR failure rate was significantly different between protocols 1 and 2 (p = 0.02) while ADO rate was higher in the protocol which resulted in larger amplicon even though the trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.07). Protocols 2 and 3 differed significantly in both parameters (p = 0.0015 and p = 0.0012 for amplification failure and ADO rates respectively). Protocols 1 and 3 differed significantly in ADO ( p = 0.02) but not in PCR failure rate.

Table 2.

AF and ADO rates in the different protocols of HEXA gene mutation analysis

| Protocol # | Amplicon size of outer PCR (bp) | Total # of cells | AF rate (%) | ADO rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 235 | 140 | 4/136 (2.9%) | 7/136 (5.2%) |

| 1 | 276 | 200 | 20/200 (10.0%) | 18/180 (10.0%) |

| 3 | 500 | 152 | 22/152 (14.5%) | 25/130 (19.2%) |

Similar comparisons of AF and ADO rates were carried out between two cell types, peripheral lymphocytes and amniotic fibroblasts, by the analysis of three mutations (protocols 1,4 and 5). AF and ADO rates were significantly elevated in the lymphocytes as compared to fibroblasts for all three protocols (Table 3). ADO rate was significantly higher in lymphocytes than in culture fibroblasts (p = 0.0007), while similar results have been obtained for AF though the difference was only of borderline significance (p = 0.057).

Table 3.

AF and ADO rates of the different mutations in the two single cell types

| Cell type | Total # of cells | AF rate (%) | ADO rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphocytes | 178 | 22/178 (12.4%) | 29/156 (18.6%) |

| Amniocytes | 147 | 9/147 (6.2%)a | 6/138 (4.4%)b |

ap = 0.05 bp < 0.001

Fibroblasts are dividing cells of embryonic origin while lymphocytes are differentiated non dividing cells with a compact nucleus. We tested the hypothesis that DNA from dividing cells have better amplification qualities by analyzing peripheral lymphocytes without or following mitosis induction. Suspensions of lymphocytes were treated with phytohemaglutinin (PHA) to induce cell division and single cells were isolated from induced and non-induced cultures. Mitosis rate was about 14% in the induced cultures and 0% in the non-induced control. Amplification protocol 1 (Table 1) was employed on 61 induced single cells and 52 controls, ADO rate was significantly reduced in dividing lymphocytes as compared to non induced cells kept in the same culture conditions (22/61,36% and 36/52, 69% in induced and non-induced lymphocytes respectively, p = 0.0008). The viability of all cultures was tested by trypan blue which is known to be excluded by viable cells. We found no significant difference between the induced and non-induced cells.

The inner amplification products of protocol 1 are 159 bp long wild type and 163 bp mutated alleles. Protocols 4 and 5 are aimed at detection of point mutations and therefore the wild type and mutated alleles produced by each protocol do not differ in size. Eighteen PCR products of protocol 1 and 16 PCR products of protocols 4 and 5 have demonstrated ADO. Fluorescence fragment analysis of 18 PCR products of protocol 1 demonstrated non-random segregation of alleles which were dropped, as compared to the dropped, point mutated alleles of protocols 4 and 5 (Table 4). These observations suggest the influence of even a small difference in fragments size on the ADO phenomenon. In 22.4% of the cases showing ADO when analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, the under-amplified allele was detected by the fluorescence fragment analysis. ADO in these cases is better described as preferential amplification.

Table 4.

Segregation of alleles dropped out, according to mutation types

| Alleles dropped | aInsertion mutation | bPoint mutations |

|---|---|---|

| Mutated alleles | c16 | 7 |

| Wild type alleles | c2 | 9 |

a+1278 TATC in HEXA gene

b854A>C in ASPA gene and IVS20+6 T>C in IKBKAP gene

cp = 0.007 by Fisher’s exact test

Discussion

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis, based on single embryonic cell testing, has already been applied in a wide range of genetic diseases and chromosomal aberrations. Reports also exist in relation to the credibility and precision of these diagnostic methods [2, 9–14, 21–23]. We further evaluated the AF and ADO rates in a large population of single cells obtained from individuals heterozygous for a mutation in one of the three genes, HEXA, IKBKAP and ASPA. Each of these mutations underlies a relatively common disease among the Ashkenazi Jewish population; Tay Sachs, familial dysautonomia and Canavan disease with carrier frequencies of 1:29–1:55. The participants of the study were healthy Ashkenazi Jews who were diagnosed as mutation carriers prior to single cell collection. The mutation detection techniques used for single cells analysis were identical to those used in the routine screening tests. The genes analyzed are well characterized and there are no documentations regarding special secondary structures or imprinting in those loci. In the case of prenatal diagnosis, molecular tests were carried out routinely together with the parents’ DNA to identify possible polymorphisms in the family.

The amplification efficiency in this study was found to be compatible with other reports examining different loci in the genome [9, 23, 24]. Our improved technique of individual cell isolation ensured the collection of individual cells, thus overcoming some of the technical obstacles stemming from aggregates of cells which might cause inefficient cell lysis and amplification failure. Full or partial degradation of the cell’s DNA was also reported to affect amplification quality [9, 10, 25].

The effect of the outer PCR product size was evaluated with the two mutations in the HEXA gene (protocols 1–3, Table 1). The rate of PCR failure was significantly dependent on the size of the amplified fragment even with the small difference of 4 nucleotides. The cause might not be the size difference only, but rather a structural twist or bend of the mutated fragments in the reaction mixture.

Dependency on PCR product size was already documented elsewhere [9, 26]. Since all cells were isolated and processed by the same technician, we believe that the differences were not the mere result of human imprecision. Most of the blood cells were lymphocytes, however, other mononuclear cell types probably remained in the suspensions from which the single cells were isolated. Single cells were isolated from the cultures that have been previously used for the molecular diagnosis. No synchronizing treatment has been applied, thus, different cell-cycle stages exist in the suspension. Previously published reports confront similar experimental conditions [9–11, 27]. All the above mentioned factors could potentially have some effect on the reaction efficiency (changes in nuclear membranes, intracellular interactions with the DNA etc.). We think that the large size of the examined cell population (above 700 cells) and the fact that the cells were collected randomly ensure the results reliability.

Complete PCR failure occurs most likely early during the first PCR rounds and therefore no products are available for further amplification or analysis. On the other hand, ADO may represent marked preferential amplification of one of the two alleles in a heterozygous cell and is a pure result of PCR reaction kinetics. In such cases, the supposed “unseen” allele may be detected by more sensitive methods. In the present study we also documented an association between cell type and amplification quality. ADO and AF were significantly elevated in peripheral lymphocytes as compared to amniotic cultured cells. The association was observed in the diagnosis of three mutations in the three genes analyzed (protocols 1,3,5) and the combined data show a significant difference between the examined cell types especially in ADO rate (Table 3). In another report where buccal cells were compared to blastomeres, no significant differences in amplification efficiency and ADO were found [9]. 7–15% of blastomeres are predicted to be haploid [27]. This is not the case with amniotic cells (fibroblasts), in particular since chromosomal analysis is carried out in all samples and a normal karyotype was established in all of them. Many factors discriminate between cell types, one basic difference in our system was that lymphocytes have no division potential. The nucleus of differentiated non dividing lymphocytes in very compact and the DNA might be less accessible to external reagents, under our lysis conditions. To investigate the possibility that the ability to divide have an impact of PCR quality, lymphocytes were induced to divide in cultures. The ADO rate in the induced suspension (which possess 14% mitosis rate) was about twice smaller than in non-induced single lymphocytes. The nucleus of the differentiated lymphocytes is very compact and its DNA might be much less available to the external amplification reagents than in the case of the dividing cells. An additional issue to consider is the fact that part of the cells in a dividing population contained more than one genome set (those between S phase and the last stages of mitosis). However we do not think that the extra amount of cellular DNA was sufficient to account for the difference in the ADO rate. The overall high ADO rates in both populations were most likely caused by the unfavorable conditions of being in culture. Consequently, single lymphocytes might not be the ideal model for designing and tuning a PGD system. Cells obtained from a dividing population provide a better model, as they are more similar to the clinical set-up of single blastomeres.

The present study quantified some aspects of AF and ADO, the major obstacles in PCR based single cell diagnosis. The size of the outer PCR fragment has a concrete effect as the reaction tends to be less efficient in larger fragments. Division potential has also an effect on ADO rate. Our observations further support the very much accepted conclusion that each single cell based diagnosis system should be specifically and very carefully tested and tuned before applying to clinical PGD. It is also very important to use highly sensitive detection methods.

Footnotes

Capsule

Allele dropout rate in single cell based diagnosis requires careful adjustment concerning cell type, division potential and PCR fragment size that significantly affect the system.

References

- 1.Handyside AH, Pattinson JK, Penketh RJ, Delhanty JD, Winston RM, Tuddenham EG. Biopsy of human preimplantation embryos and sexing by DNA amplification. Lancet. 1989;1:347–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)91723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells D, Sherlock JK. Strategies for preimplantation genetic diagnosis of single gene disorders by DNA amplification. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:1389–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199812)18:13<1389::AID-PD498>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braude P, Pickering S, Flinter F, Ogilvie CM. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:941–53. doi: 10.1038/nrg953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bick DP, Lau EC. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:559–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goossens V, Harton G, Moutou C, Scriven PN, Traeger-Synodinos J, Sermon K, et al. ESHRE PGD Consortium data collection VIII: cycles from January to December 2005 with pregnancy follow-up to October 2006. Hum Reprod. 2008;1-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Harper JC, Die-Smulders C, Goossens V, Harton G, Moutou C, Repping S, et al. ESHRE PGD consortium data collection VII: cycles from January to December 2004 with pregnancy follow-up to October 2005. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:741–55. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sermon K, Rycke M. Single cell polymerase chain reaction for preimplantation genetic diagnosis: methods, strategies, and limitations. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;132:31–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-298-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray PF, Ao A, Taylor DM, Winston RM, Handyside AH. Assessment of the reliability of single blastomere analysis for preimplantation diagnosis of the delta F508 deletion causing cystic fibrosis in clinical practice. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:1402–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199812)18:13<1402::AID-PD500>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piyamongkol W, Bermudez MG, Harper JC, Wells D. Detailed investigation of factors influencing amplification efficiency and allele drop-out in single cell PCR: implications for preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2003;9:411–20. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gag051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Findlay I, Ray P, Quirke P, Rutherford A, Lilford R. Allelic drop-out and preferential amplification in single cells and human blastomeres: implications for preimplantation diagnosis of sex and cystic fibrosis. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1609–18. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.6.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rechitsky S, Strom C, Verlinsky O, Amet T, Ivakhnenko V, Kukharenko V, et al. Allele dropout in polar bodies and blastomeres. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15:253–7. doi: 10.1023/A:1022532108472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dreesen JC, Bras M, Coonen E, Dumoulin JC, Evers JL, Geraedts JP. Allelic dropout caused by allele-specific amplification failure in single-cell PCR of the cystic fibrosis delta F508 deletion. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;13:112–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02072531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gitlin SA, Lanzendorf SE, Gibbons WE. Polymerase chain reaction amplification specificity: incidence of allele dropout using different DNA preparation methods for heterozygous single cells. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;13:107–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SA, Yoon JA, Kang MJ, Choi YM, Chae SJ, Moon SY. An efficient and reliable DNA extraction method for preimplantation genetic diagnosis: a comparison of allele drop out and amplification rates using different single cell lysis methods. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:814–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamvik JO. Separation of lymphocytes from human blood. Acta Haematol. 1996;35:294–303. doi: 10.1159/000209135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sermon K, Lissen W, Nagy ZP, Steirteghem, Liebaers I. Simultaneous amplification of the two most frequent mutations of infantile Tay-Sachs disease in single blastomers. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2214–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruano G, Kidd KK. Modeling of heteroduplex formation during PCR from mixture of DNA templates. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:112–6. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myerwitz R. Splice junction mutation in some Ashkenazi Jews with Tay-Sachs disease: evidence against a single defect within the ethnic group. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3955–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matalon R, Michals K, Gashkoff P, Kaul R. Prenatal diagnosis of Canavan disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15:392–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02435985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong J, Edelmann L, Bajwa AM, Kornreich R, Desnick RJ. Familial dysautonomia: detection of the IKBKAP IVS20+6T>C and R696P mutations and frequencing among Ashkenazi Jews. Am J Med Genet. 2002;110:253–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray PF, Handyside AH. Increasing the denaturation temperature during the first cycles of amplification reduces allele dropout from single cells for preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:213–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Hashemite N, Delhanty JD. A technique for eliminating allele specific amplification failure during DNA amplification of heterozygous cells for preimplantation diagnosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 1997;3:975–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/3.11.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handyside AH. Clinical evaluation of preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:1345–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199812)18:13<1345::AID-PD505>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornhill AR, Snow K. Molecular diagnostics in preimplantation genetic diagnosis. J Mol Diagnostics. 2002;4:11–29. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verlinsky Y, Kuliev A. Preimplantation polar body diagnosis. Biochem Mol Med. 1996;58:13–7. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Findlay I, Matthews P, Quirke P. Multiple genetic diagnoses from single cells using multiplex PCR: reliability and allele dropout. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:1413–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199812)18:13<1413::AID-PD496>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo HC, Ogilvie CM, Handyside AH. Chromosomal mosaicism in cleavage-stage human embryos and accuracy of single-cell genetic analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15:276–80. doi: 10.1023/A:1022588326219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]