Abstract

Polymeric micelles are used as pharmaceutical carriers to increase solubility and bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. Different ligands are used to prepare targeted polymeric micelles. Earlier, we developed the method for use of specific landscape phage fusion coat proteins as targeted delivery ligands and demonstrated the efficiency of this approach with doxorubicin-loaded PEGylated liposomes. Here, we describe a MCF-7 cell-specific micellar formulation self-assembled from the mixture of the micelle-forming amphiphilic polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE) conjugate, MCF-7-specific landscape phage fusion coat protein, and the hydrophobic drug paclitaxel. These micelles demonstrated a very low CMC value and specific binding to target cells. Using an in vitro co-culture model, FACS analysis, and fluorescence microscopy we showed that MCF-7 targeted phage micelles preferential bound to target cells compared to non-target cells. As a result, targeted paclitaxel-loaded phage micelles demonstrated a significantly higher cytotoxicity towards target MCF-7 cells than free drug or non-targeted micelle formulations, but failed to show such a differential toxicity towards non-target C166 cells. Overall, cancer cell-specific phage proteins identified from phage display peptide libraries can serve as targeting ligands (“substitute antibody”) for polymeric micelle-based pharmaceutical preparations.

Keywords: Drug delivery, Polymeric micelles, PEG-PE, Phage display, Landscape phage, Paclitaxel, Tumor targeting, Breast cancer

Introduction

One of strategies used to improve the toxicity profile of cancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy, i.e. to enhance its activity against cancer cells and decrease undesirable side-effects onto normal cells, is to specifically target cytotoxic drugs to tumor tissues and limit their access to normal tissues1. This have been achieved, for example, by coupling monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or their fragments (Fab’, scFv) with radionuclides, toxins, or drug-loaded pharmaceutical nanocarriers, such as liposomes or polymeric micelles2-5. Indeed, antibody-targeted therapeutics including the anti-CD20 yittrium 90 conjugate Ibritumomab® (IDEC Pharmaceuticals) and the anti-CD33 calicheamicin conjugate Mylotarg® (Wyeth/AHA) have clearly demonstrated significantly enhanced antitumor activity due to the ability of the antibody to specifically direct antitumor agents to target tumor cells1, 6, 7. While the improved pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of antibody-directed anticancer preparations justify the use of antibody-based approaches, still the high cost of monoclonal antibodies and their relatively low stability in biological media represent important issues. This promotes an ongoing search for alternative targeting ligands with small size, low cost, and good in vivo stability.

Development of phage display technology has facilitated the discovery of bioactive peptides, which interact specifically with molecular targets over-expressed on the surface of tumor cells8-10. Numerous tumor- and/or tumor vasculature-homing peptides have been successfully identified from phage-displayed peptide libraries11-13. Recently, we have screened a landscape phage protein bearing a MCF-7-specific peptide from an 8-mer landscape library (f8/8) via a biopanning protocol against MCF-7 cells14. We have also reported a novel and straightforward method for making tumor-targeted nanomedicines by anchoring the whole specific phage coat protein (simple-to-prepare, cheap and stable “substitute antibody”) into the liposomal bilayer of doxorubicin-loaded PEGylated liposomes (Doxil®) without additional conjugation with lipophilic moieties. The improved Doxil targeting with the cancer cell-specific phage protein resulted in a much better uptake of doxorubicin into target cells and more effective cell killing14, 15.

However, it is difficult to extend the advantages of phage-liposomes to targeted delivery of water-insoluble drugs. It was shown that hydrophobic drugs, such as paclitaxel, are difficult to package stably within the liposomal lipid bilayer because of their bulky structure16, 17. Additionally, it was reported that the liposomal paclitaxel rapidly partitions out of liposomes upon in vivo administration, which makes it difficult to deliver paclitaxel to target cells by means of ligand-targeting liposomes 17. On the other hand, water-insoluble drugs represent an important category of anticancer therapeutics. Increased hydrophobicity of drugs promotes their passage across the cell membrane structure, whereas the low water-solubility of these drugs results in poor bioavailability - a serious challenge to parenteral drug delivery16.

Polymeric micelles represent an efficient system for the delivery of a broad variety of hydrophobic drugs16.18. Loading such drugs into the hydrophobic micelle core dramatically increases drug solubility and bioavailability. Due to their nanoscale size, polymeric micelles penetrate readily the tumor vasculature and accumulate passively on tumor sites via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect19.

The amphiphilic nature of phage fusion coat protein, which allowed its anchoring into the liposomal membrane, should also allow its stable incorporation into polymeric micelles. In this study we have attempted to build mixed micelles made of polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE) conjugate and tumor-specific phage protein, load such mixed micelles with a water-insoluble anti-cancer drug and target them to cancer cells. Unlike the traditional protocols for preparing targeting micelles, such as immunomicelles, which often require specific chemistry efforts to conjugate mAbs to the corona of the polymeric micelle2, 16, 18, our approach is based completely on a self-assembly process and does not require any chemical modification. A phage protein with high affinity and selectivity towards MCF-7 cells and paclitaxel (PCT) were used in this study. Uptake and cytotoxicity experiments with MCF-7 cells in vitro demonstrated that the targeted phage-micelles bind better with target cells and demonstrate a significantly enhanced cytotoxicity compared to free drug and non-targeted micelles.

Experimental Section

Materials and Reagents

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)2000] (ammonium salt; PEG2000-PE ) and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (ammonium salt, Rho-PE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Paclitaxel (PCT) was from Cedarburg Pharmaceuticals (Beverly, MA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), acetonitrile (HPLC grade), and methanol (HPLC grade) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Sodium cholate was from Sigma (St.Louis, MO). Pyrene was purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc. (Milwaukee, WI). CellTiter-Blue® assay kit was from Promega (Madison, WI). Fluor Mounting Medium was from Trevigen Inc (Gaithersburg, MD). MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma (HTB 22 ™) cells, C166-GFP (CRL-2583 ™) and C166 (CRL-2581 ™) mouse yolk sac endothelial cells, as well as NIH3T3 (CRL-1658 ™) mouse fibroblasts were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). All cells were grown as recommended by the ATCC at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Phage Protein

Phage selection and phage protein purification have been performed as described by us earlier14.

Preparation of Phage-PEG-PE Micelles

For FACS and fluorescence microscopy study, 5 mM of PEG2000-PE was mixed with traces of rhodamine-PE in chloroform. For Transmission electron microscopy and cytotoxicity studies, 5 mM of PEG2000-PE in chloroform was mixed with PCT in methanol at 1.5:100 drug-to-lipid weight ratios. After the evaporation, the lipid film formed was hydrated with MCF-7 specific phage protein in 10 mM of sodium cholate at protein to polymer ratio 1: 200 by weight, followed by vortexing and overnight dialysis against PBS, pH 7.4 to remove sodium cholate. Non-incorporated PCT was excluded by filtration of the micellar suspension through a 0.2 μM polycarbonate membrane. As controls, drug-free plain PEG-PE micelles, drug-free phage-PEG-PE micelles, PCT-loading plain PEG-PE micelles and unrelated streptavidin-targeted-phage-PEG-PE micelles were prepared using the similar procedure. To evaluate effect of phage protein density on targeted cellular uptake, protein to polymer ratios 1:400, 1:100 by weight were also used.

Size and Size Distribution of Phage-PEG-PE Micelles

Micellar size was measured by the dynamic light scattering. Briefly, Samples were diluted in PBS, pH7.4 and measured using a Beckman Coulter N4 Plus Particle analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) with a scattering angle of 90° and particle size range measurements of 1-1000nm. The measurements were run three times.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

The morphology of micelles was detected using a JEOL JEM-1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA). Micelle samples 10 μl were dropped on a grid coated with Formvar and carbon film and were negative stained using 1.5-2% phosphotungstic acid. After air-dried at room temperature. TEM image is obtained on the transmission electron microscopy operating at an accelerating voltage of 65 kV.

Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) Determination

The pyrene method was used to determine CMC of plain micelles and phage-micelles. Briefly, 1 ml of pyrene stock solution in chloroform with a pyrene concentration of 1mg/ml was added to each test tube, and the chloroform was evaporated under vacuum. Subsequently, the crystalline pyrene was incubated with varying concentrations (ranging from 1×10−4 M to 5 ×10−7 M) of plain micelles or phage-micelles overnight on a Lab Line Environ shaker (Lab Recyclers Inc, USA) at room temperature. The insoluble pyrene was removed by filtration through the 0.2 μM polycarbonate membrane, followed by the determination of the pyrene amount solubilized in the micelles using an F-2000 fluorescence spectroscopy (Hitachi, Japan) with the excitation wavelength of 339 nm and emission wavelength of 390 nm. The CMC value corresponds to the concentration of micelles at which there is a sharp increase in the fluorescence of the solution due to the formation of micelles and partial pyrene solubilization.

Drug Loading

The amount of PCT in the micelle formulation was detected using a reversed phase D-7000 HPLC system equipped with a diode array and fluorescence detector and Spherisorb ODS2 column (Hitachi, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of water and acetonitrile with volume ratio 60:40. The elution was performed at a rate of 1.0 ml/min. PCT was detected from injected sample (50μL) at 227nm.

Uptake of Phage-Micelles by MCF-7 Cells

MCF-7 cells were grown in 12.5 cm2 flasks in MEM with 10% serum until 70-80% confluence. Cells were incubated with 75 μM of rhodamine-labeled plain- or phage- micelles for 1 h. After washed 3 times with PBS, pH 7.4, cells were detached and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by flow cytometry analysis. A right shift on the x axis of the histogram plot indicated the binding of the rhodamine-labeled micelles.

FACS Analysis of Selective Binding of Phage-Micelles with Target MCF-7 Cells

Target MCF-7 cells or non-target NIH3T3 cells were co-cultured with non-target C166 endothelial cells expressing GFP at 1:1 ratio and seeded in 12.5cm2 flasks in MEM with 10% serum. After co-culture until 70-80% confluence, cells were incubated with 75 μM of rhodamine-labeled plain- or phage-micelles for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed 3 times with PBS (pH 7.4), detached and collected by centrifugation. The cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by flow cytometry analysis. Binding of the rhodamine-labeled micelles was detected as a right shift of the population on the x axis (FL-2H, Red). The percent of micelle-associated cells was calculated as follows:

- For MCF-7 cells or NIH3T3 cells,

- The percent of micelle-associated cells = R3 / (R1+R3) × 100%.

- For C166-GFP cells,

- The percent of micelle-associated cells = R4 / (R2+R4) × 100%.

The binding selectivity ratio was defined as the percent of micelle-associated MCF-7 cells or the percent of micelle-associated NIH3T3 cells divided by the percent of micelle-associated C166-GFP cells as follows:

The binding selectivity ratio = [R3 / (R1+R3)] / [R4 / (R2+R4)].

Selective Binding of Phage-Micelles with Target Cells Revealed by Fluorescence Microscopy

MCF-7 cells and C166-GFP cells were co-grown on 6-well plates at a density of 2×105 cells/well for 24h at 37°C, and incubated with 75 μM of rhodamine-labeled plain- or phage-micelles in MEM with 10% serum for 30 min at 37°C. After washed 3 times with PBS, the coverslip was placed onto a glass slide over the fluorescence mounting medium. The images were acquired by a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Japan) at 40 × magnification with FITC or TRITC filter.

Cytotoxicity

Target MCF-7 cells or non-target C166 cells were seeded into 96 well microplates at a density of 5×104 cells/well (for MCF-7 cells) or 3.5×104 cells/well (for C166 cells), respectively. After growth to 50-60% confluence, cells were treated with varying concentration of free PCT in DMSO, PCT-loaded plain micelles, PCT-loaded micelles modified with unrelated streptavidin-specific phage protein (PCT-loaded SA-phage-micelles), PCT-loaded micelles modified with MCF-7-targeted phage protein (PCT-loaded MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles), control drug-free micelles modified with unrelated streptavidin-specific phage protein (drug-free-SA-phage-micelles), and targeted drug-free micelles modified with MCF-7-specific phage protein (drug-free MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles) in MEM (for MCF-7 cells) or DMEM (for C166 cells) with 10% serum for 72h. Cells were then washed once with PBS, pH 7.4, and incubated with fresh complete medium (100 μl/well) along with the CellTiter-Blue® assay reagent (20 μl/well) for 2h at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a multi-detection microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT) with 525/590 nm excitation/emission wavelengths.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of the results was analyzed using SPSS (version 16). Differences between experimental groups were compared using ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. The results were considered statistically significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

Characterization of Phage-Micelles

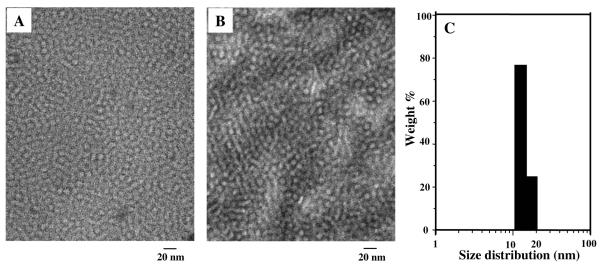

TEM image of phage micellar formulations showed mono-disperse particles with spherical shape (Figure 1A). Incorporation of phage protein and paclitaxel had no noticeable change in the geometry or size of plain PEG-PE micelles (compare Figure 1A, 1B). Size of the MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles by dynamic light scattering measurement was within a 13.3-to-20.5 nm interval (Figure 1C), which is consistent with that of typical PEG-PE micelles16. A 20-day-stability study showed that the micelle size did not change.

Figure 1. Characterization of micellar formulations.

A) TEM micrograph of paclitaxel-loaded phage PEG-PE micelles; B) TEM micrograph of drug-free plain PEG-PE micelles; C) Size distribution of phage micelles measured by dynamic light scattering.

Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) Determination

Our CMC value of plain PEG-PE micelles was 1.62×10−5 M, which is in consistence with reported data16, 21, while the CMC value of MCF-7-targeted phage-PEG-PE-micelles was slightly lower at 7.2×10−6 M, indicating greater stability of mixed micelles.

Drug Loading

The results of three independent measurements showed that the final preparation of MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles contained 157.7 ± 22.3 μg/ml of paclitaxel, while plain micelles contained 165.7 ± 38 μg/ml of paclitaxel, i.e. there was no effect of phage protein presence on the drug incorporation into micelles.

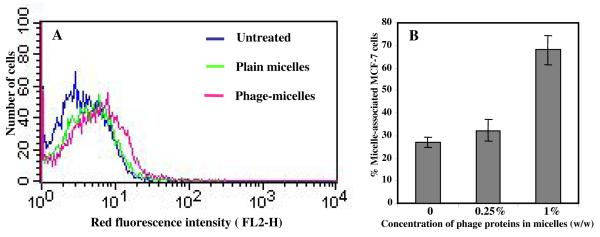

Uptake of Phage-Micelles by MCF-7 Cells

Uptake of MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles by MCF-7 cancer cells was determined using FACS analysis in comparison with control plain micelles. The phage-micelles showed a stronger uptake by MCF-7 cells than plain micelles indicated as a stronger right shift along the x-axis of the histogram (Figure 2 A). The binding affinity increased with increased concentration of the phage proteins present in the micellar formulation (Figure 2 B).

Figure 2. FACS analysis of micellar uptake by MCF-7 cells indicated as fluorescence intensity of cell-associated rhodamine-labeled micelles.

A) The histogram plot of the binding of rhodamine-labeled MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles and plain micelles to MCF-7 cells; B) Effect of concentration of phage proteins on binding affinity of micellar formulations to MCF-7 cells (mean ± SD, n=6).

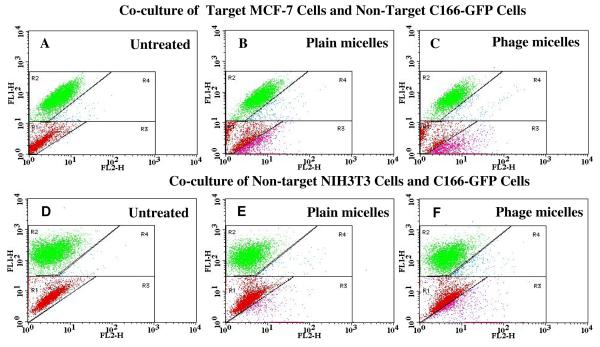

FACS Analysis of Selective Binding of Phage-Micelles with Targeted MCF-7 Cells

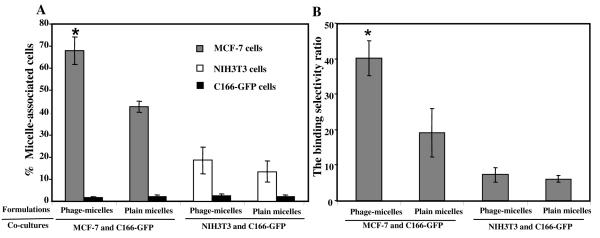

To investigate the selectivity of phage-micelle interaction with target cancer cells compared to normal cells, we used a co-culture assay, in which target cancer MCF-7 cells were co-grown with non-target, non-cancer endothelial cells - C166-GFP. FACS analysis revealed two distinct co-culture cell populations based on their different green fluorescence intensity (FL1-H green): MCF-7 cells (Figure 3A) or NIH3T3 cells (Figure 3D) are within Region 1 (R1) as shown in red and C166-GFP cells are in Region 2 (R2) as shown in green (Figure 3A, 3D). After the treatment with rhodamine-labeled, MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles in the co-culture with MCF-7 cells and C166-GFP cells, a significantly higher percent of MCF-7 cells were right shifted into the region 3 (R3) compared to C166-GFP cells right-shifted into the region 4 (R4) (Figure 3C). Statistical analysis (Figure 4A) showed that MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles bound to ca. 67 % of MCF-7 cells (R3 in Figure 3C) and to only 1.67% of C166-GFP cells (R4 in Figure 3C), indicating a significant binding selectivity towards the target cells. It has to be noted here that control plain micelles also bound to MCF-7 cells (R3 in Figure 3B) better than to C166-GFP cells (R4 in Figure 3B), however the phage micelles targeted MCF-7 cells with a significantly higher binding selectivity ratio (ca. 40) than plain micelles (ca. 19) (Figure 4B), confirming the role that MCF-7-specific phage protein played in preferential targeting of MCF-7 cells. In the negative control co-culture with non-target NIH3T3 and C166-GFP cells, the treatment with phage micelles resulted in 18% of shifted NIH3T3 (R3 in Figure 3F) and 2.4% of C166-GFP (R4 in Figure 3F), which is much lower compared to the association of the phage-micelles with MCF-7 cells (Figure 4A). Control treatment with plain micelles in the co-culture of NIH3T3 and C166-GFP cells, showed results comparable to that of the phage-micelles with 13.4% of shifted NIH3T3 cells (R3 in Figure 3E) and 2.1% of shifted C166-GFP cells (R4 in Figure 3E) and a similar binding selectivity ratio (Figure 4B), confirming the preferential binding of the phage-micelles to target MCF-7 cells.

Figure 3. FACS analysis of cell binding of micellar preparations in co-culture systems.

Co-culture composed of target MCF-7 cells and non-target C166-GFP cells and control co-culture composed of non-target NIH3T3 cells and C166-GFP cells were incubated with either plain micelles or MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles for 1h, and micelle-associated cells ( as red fluorescence increase ) were analyzed using FACS. The dot plots were inserted into four regions (R1, R2, R3, and R4). FL1-H (green); FL2-H (red); A) Untreated co-culture of MCF-7 cells and C166-GFP cells. Red dots in R1 region show the location of untreated MCF-7 cells and green dots in R2 region show the location of untreated C166-GFP cells; B) Plain micelle-treated co-culture of MCF-7 cells and C166-GFP cells. Pink dots in R3 region show plain micelle-associated MCF-7 cells, and blue dots in R4 show plain micelle-associated C166-GFP cells; C) MCF-7-targeted phage-micelle-treated co-culture of MCF-7cells and C166-GFP cells. Pink dots in R3 region show phage-micelle-associated MCF-7 cells, and blue dots in R4 show phage-micelle-associated C166-GFP cells; D) Untreated control co-culture of NIH3T3 cells and C166-GFP. Red dots in R1 region show the location of untreated NIH3T3 cells, and green dots in R2 region show the location of untreated C166-GFP cells; E) Plain micelle-treated co-culture of NIH3T3 and C166-GFP cells. Pink dots in R3 region show plain micelle-associated NIH3T3 cells, and blue dots in R4 show plain micelle-associated C166-GFP cells; F) MCF-7-targeted phage-micelle-treated co-culture of NIH3T3and C166-GFP cells. Pink dots in R3 region show phage-micelle-associated NIH3T3 cells and blue dots in R4 show phage-micelle-associated C166-GFP cells.

Figure 4. Quantitative analysis of the binding of micellar preparations with cocultured target and non-target cells by FACS.

A) Micelle-associated cells indicated as the intensity of cell population shifted to the region with higher red fluorescence; B) The binding selectivity ratios defined as the percent of micelle-associated MCF-7 cells or the percent of micelle-associated NIH3T3 cells divided by the percent of micelle-associated C166-GFP cells (* p <0.05, mean ± SD, n=6).

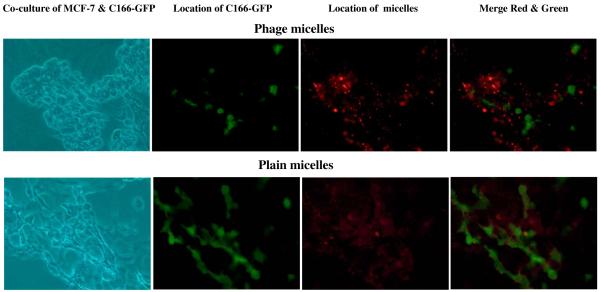

Fluorescence Microscopy of Selective Binding of Phage-Micelles with Target Cells

Using the fluorescence microscopy, the selective binding of phage-micelles to target cancer cells rather than to normal cells was further confirmed in the co-culture model composed of target MCF-7 cancer cells and non-target, non-cancer endothelial C166-GFP cells. Based on green fluorescence of C166-GFP cells, these cells were distinguished from MCF-7 cells and visualized under a fluorescence microscopy. The treatment with rhodamine-labeled MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles showed the phage-micelles specific binding to MCF-7 cells but not to C166-GFP cells, revealed as a lack of co-localization of red and green fluorescence (Figure 5). Control plain micelles showed non-specific binding to both MCF-7 cells and C166-GFP cells, indicating that the selective targeting of the phage-micelles to MCF-7 is mediated by the phage protein (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The binding of rhodamine-labeled MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles and plain micelles to co-culture MCF-7 and C166-GFP cells revealed by florescence microscopy.

Green fluorescence is produced by C166-GFP cells; Red fluorescence labels MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles.

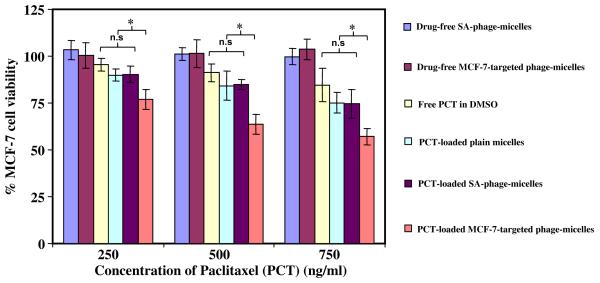

Cytotoxicity toward Tumor Cells

CellTiter-Blue assay (Figure 6) demonstrated a significantly higher tumor cell killing by 72h treatment of PCT-loaded MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles compared to controls. While both drug-free MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles and drug-free non-targeted SA-phage-micelles did not show any cytotoxicity toward MCF-7 cells, and free PCT in DMSO and PCT-loaded plain micelles caused only limited tumor cell killing at the concentration tested, the MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles provoked a significantly higher cell death at the same PCT concentrations. The PCT-loaded non-targeted SA-phage-micelles did not trigger an increased MCF-7 cell killing compared to PCT-loaded non-targeted plain micelles, but showed much lower cytotoxicity than MCF-7-targeted phage- micelles (Figure 6). This result further confirmed the role of MCF-7-targeted phage fusion protein in MCF-7 cell death. With control non-target C166 cells, no difference in cytotoxicity of PCT-loaded MCF-7 targeted phage-micelles, free PCT, PCT in plain PEG-PE micelles, and PCT in irrelevant SA-phage-micelles at the same concentration of PCT tested. Taken together, these data confirm the selective cytotoxicity of MCF-7 targeted phage-micelle only toward target cells. Similar results were observed in a delayed viability test, where cytotoxicity was determined after 48h of drug treatment and additional 12h incubation in drug-free medium.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity of micelle preparations toward MCF-7 cells after 72h treatment with MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles and various controls, including free PCT in DMSO, PCT-loaded plain micelles, irrelevant SA-phage-micelles, drug-free MCF-7-targeted phage-micelles and drug-free SA-phage-micelles (* p <0.05, mean ± SD, n=6).

Discussion

The rational for the modification of paclitaxel-loaded PEG-PE micelles with phage protein was to combine favorable properties of both polymeric micelle-based drug delivery system and a cancer cell-specific phage peptide as a targeting ligand. Polymeric micelles made from amphiphilic block-copolymer have already demonstrated their ability to enhance solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble therapeutics16, 18. PEG-PE as the micelle-forming material of choice in this study offers considerable advantages. The corona-forming PEG chain block is hydrophilic and biocompatible, provides a steric protection from non-specific uptake by mononuclear phagocytic system and allows for prolonged circulation in the blood. The micelle core made of phospholipid PE residues with two long hydrophobic acyl groups is intended for solubilzation and entrapment of poorly soluble drugs16, 18. Although nano-sized polymeric micelles are able to take advantage of leaky tumor vasculature and accumulate passively within tumor sites via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect19, still it is believed that attachment of targeting moieties onto the micelle surface potentates a higher efficacy of micelle-loaded antitumor agents18, 20, 21. In fact, several successes in this use of immunomicelles have validated the concept2, 21.

Advances in phage display now allow us to integrate this technology with nanocarrier-based drug delivery8, 9. Earlier, we reported on the use of the landscape phage fusion protein carrying the tumor-cell binding peptide DMPGTVLP for liposome targeting to cancer cells14. The binding affinity and selectivity of the phage protein are well-retained after its incorporation into the liposomal bilayer, and phage-targeted drug-loaded liposomes demonstrated more effective tumor cell killing. Furthermore, we have found that the phage protein provides additional advantages to the system, especially for intracellular drug delivery, such as facilitated endosomal escape and cytoplasmic delivery22. Therefore, we expected that the use of the phage protein (DMPGTVLP) combined with another drug delivery system (paclitaxel-loaded PEG-PE micelles) should increase such a system‘s antitumor activity.

Ideally, a self-assembly drug delivery system should spontaneously form from the blend of drug carrier molecules, drug cargoes and targeting components. The targeted phage protein-micelle delivery system we present here, meets such criteria: a simplified preparation without chemical modification. The phage protein contains a hydrophilic N-terminus (amino acids 1-26) and C-terminus (amino acids 45-55), and a highly hydrophobic segment (amino acids 27-40). One can expect that the amphiphilic structure of this protein will allow its spontaneous assembly with other micelle-forming components to produce drug-loaded mixed micelles. The analysis of our preparation confirms the formation of nanoassemblies with a size and stability (CMC) similar to that of PEG-PE-based micelles16, 18.

Considering the fact that the peptides are frequently a subject of the fast protoeolytic degradation9, 23, the incorporation of phage protein into the micellar structure with the binding peptides being shielded by the neighboring PEG chains in the micellar corona may potentially slow down the peptide degradation by the digestive enzyme presented in biological surrounding. As a matter of fact, a recent study showed that TAT peptide incorporated into PEG-PE-based micelles as an amphiphilic TAT peptide conjugate was well protected against trypsin proteolysis as a result of the shielding of TAT peptide moieties by PEG chain and was also stable in human blood plasma24.

On the other hand, there could be a concern that the presence of PEG chain could set up a steric barrier between phage binding peptides and targeted molecular receptors on the surface of target cells. However, this potential problem could be addressed by controlling the length of the PEG chain used, selecting one which produced a reasonable balance between the retention of target affinity of the micelle-incorporated phage protein and the protective role of PEG. This is a subject of our current studies on the optimization of phage protein-targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers.

As expect, the improved phage-micelle targeting with the cancer cell-specific phage protein resulted in a much more effective cell killing, additionally confirming the preservation of specific activity of the phage protein when associated with micelles.

Overall, we exploited the amiphiphilic character of the cancer cell-specific phage protein, and prepared targeted phage-micelles for selective delivery of paclitaxel to cancer cells. Our method of preparation of targeted micelles is simple and requires no chemical modification, and demonstrates that cancer cell-specific phage proteins identified from phage display peptide libraries can serve as specific targeting moieties (“substitute antibodies”) for a next generation of micellar tumor-targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant # 1 R01 CA125063-01 and the Animal Health and Disease Research grant 2006-9, College of Veterinary Medicine at Auburn University to Valery A. Petrenko.

References

- 1.Allen TM. Ligand-Targeted Therapeutics in Anticancer Therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:750–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torchilin VP, Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Papahadjopoulos-Sternberg B. Immunomicelles: Targeted Pharmaceutical Carriers for Poorly Soluble Drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6039–6044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvatore G, Beers R, Margulies I, Kreitman RJ, Pastan I. Improved Cytotoxic Activity Toward Cell Lines and Fresh Leukemia Cells of a Mutant Anti-CD22 Immunotoxin Obtained by Antibody Phage Display. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:995–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JW, Kirpotin DB, Hong K, Shalaby R, Shao Y, Nielsen UB, Marks JD, Papahadjopoulos D, Benz CC. Tumor Targeting Using Anti-Her2 Immunoliposomes. J Control Release. 2001;74:95–113. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seymour LW, Ferry DR, Anderson D, Hesslewood S, Julyan PJ, Poyner R, Doran J, Young AM, Burtles S, Kerr DJ. Hepatic Drug Targeting: Phase I Evaluation of Polymer-Bound Doxorubicin. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1668–1676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noble CO, Kirpotin DB, Hayes ME, Mamot C, Hong K, Park JW, Benz CC, Marks JD, Drummond DC. Development of Ligand-Targeted Liposomes for Cancer Therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2004;8:335–353. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JS, Gray K, Gray GS, Worland PJ, Rolfe M. Anticancer Antibodies. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:472–485. doi: 10.1309/Y6LP-C0LR-726L-9DX9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrenko V. Evolution of Phage Display: From Bioactive Peptides to Bioselective Nanomaterials. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:825–836. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.8.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori T. Cancer-Specific Ligands Identified from Screening of Peptide-Display Libraries. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2335–2343. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrenko VA, Smith GP. Phages from Landscape Libraries as Substitute Antibodies. Protein Eng. 2000;13:589–592. doi: 10.1093/protein/13.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koivunen E, Wang B, Ruoslahti E. Phage Libraries Displaying Cyclic Peptides with Different Ring Sizes: Ligand Specificities of the RGD-Directed Integrins. Biotechnology (N Y) 1995;13:265–270. doi: 10.1038/nbt0395-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda MN, Ohyama C, Lowitz K, Matsuo O, Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E, Fukuda M. A Peptide Mimic of E-Selectin Ligand Inhibits Sialyl Lewis X-Dependent Lung Colonization of Tumor Cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:450–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hetian L, Ping A, Shumei S, Xiaoying L, Luowen H, Jian W, Lin M, Meisheng L, Junshan Y, Chengchao S. A Novel Peptide Isolated from a Phage Display Library Inhibits Tumor Growth and Metastasis by Blocking the Binding of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor to Its Kinase Domain Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43137–43142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang T, D’Souza GGM, Bedi D, Fagbohum OA, Potturi P, Papahadjopoulos-Sternberg B, Petrenko VA, Torchilin VP. Enhanced Binding and Killing of Target Tumor Cells by Drug-Loaded Liposomes Modified with Tumor-Specific Phage Fusion Coat Protein. Nanomedicine (lond) 2010;5(4):563–574. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayanna PK, Bedi D, Gillespie JW, Deinnocentes P, Wang T, Torchilin VP, Bird RC, Petrenko VA. Landscape Phage Fusion Protein-Mediated Targeting of Nanomedicines Enhances Their Prostate Tumor Cell Association and Cytotoxic Efficiency. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.01.005. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torchilin VP. Micellar Nanocarriers: Pharmaceutical Perspectives. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drummond DC, Meyer O, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Papahadjopoulos D. Optimizing Liposomes for Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Agents to Solid Tumors. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:691–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torchilin VP. Targeted Polymeric Micelles for Delivery of Poorly Soluble Drugs. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2549–2559. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torchilin V. Tumor Delivery of Macromolecular Drugs Based on the EPR Effect. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.011. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinogradov S, Batrakova E, Li S, Kabanov A. Polyion Complex Micelles with Protein-Modified Corona for Receptor-Mediated Delivery of Oligonucleotides into Cells. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:851–860. doi: 10.1021/bc990037c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chekhonin VP, Kabanov AV, Zhirkov YA, Morozov GV. Fatty Acid Acylated Fab-Fragments of Antibodies to Neurospecific Proteins as Carriers for Neuroleptic Targeted Delivery in Brain. FEBS Lett. 1991;287:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang T, Yang S, Petrenko VA, Torchilin VP. Cytoplasmic Delivery of Liposomes into MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells Mediated by Cell-Specific Phage Fusion Coat Protein. Mol. Pharm. 2010 doi: 10.1021/mp1000229. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krumpe LR, Mori T. The Use of Phage-Displayed Peptide Libraries to Develop Tumor-Targeting Drugs. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2006;12:79–91. doi: 10.1007/s10989-005-9002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grunwald J, Rejtar T, Sawant R, Wang Z, Torchilin VP. TAT Peptide and Its Conjugates: Proteolytic Stability. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:1531–1537. doi: 10.1021/bc900081e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]