Abstract

Invariant NKT (iNKT) cells have been extensively studied throughout the last decade due to their ability to polarize and amplify the downstream immune response. Only recently however, have the various mechanisms underlying NKT cell activation begun to unfold. iNKT cells have the ability to respond as innate immune cells with minimal TCR involvement as well as through direct TCR recognition of glycolipid antigens. Additionally, the existence of several subsets of iNKT cells creates the potential for other unique pathways, which are not yet clearly defined. Here we provide an overview of the known mechanisms of invariant NKT cell activation, focusing on cytokine driven pathways and the resulting cytokine responses.

Keywords: Natural Killer T cells, CD1d, cytokines

Introduction

NKT cells comprise a distinct subset of immune cells expressing both a T cell receptor as well as classical NK cell markers. NKT cells have been categorized into four different groups [1]. The most studied category, consisting of type 1 NKT cells (or invariant NKT cells) is well conserved in mammals and expresses a TCR comprised of an invariant Vα14-Jα18 TCR (human Vα24-Jα18) α-chainpaired with a limited subset of TCR Vβ-chains [1]. iNKT cells respond primarily to lipid antigens presented by the non-classical MHC molecule, CD1d. iNKT cells have been described as innate immune effector cells because they are capable of rapidly responding to antigen, releasing cytokines, proliferating and producing cytolytic mediators [2–5]. Their ability to respond quickly to antigen challenge is believed to bridge the gap between the fast acting less specific innate immune system and the antigen specific adaptive response. Significant progress in understanding the function of iNKT cells has relied on α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), a strong iNKT cell agonist [6, 7]. In addition, critical tools such as CD1d tetramer [8, 9], CD1d deficient mice [10–12] and Jα18 deficient mice [6] have been instrumental in promoting recent progress in the CD1d/iNKT cell field. Using these tools and a variety of experimental strategies, researchers have been actively pursuing the identification of the self-antigen that is presented by CD1d. Another active area of research is determining the role of iNKT cells during infection. Several bacterial glycolipid ligands have been shown to activate iNKT cells, supporting a critical role for iNKT cells in some infections [13–16]. Interestingly, even in the absence of specific Ag, iNKT cells have been shown to contribute directly or indirectly to the immune response to several pathogens.

In this review, we summarize the different mechanisms of iNKT cell activation. We also discuss how these different pathways influence the cytokines secreted by iNKT cells.

1. TCR mediated activation

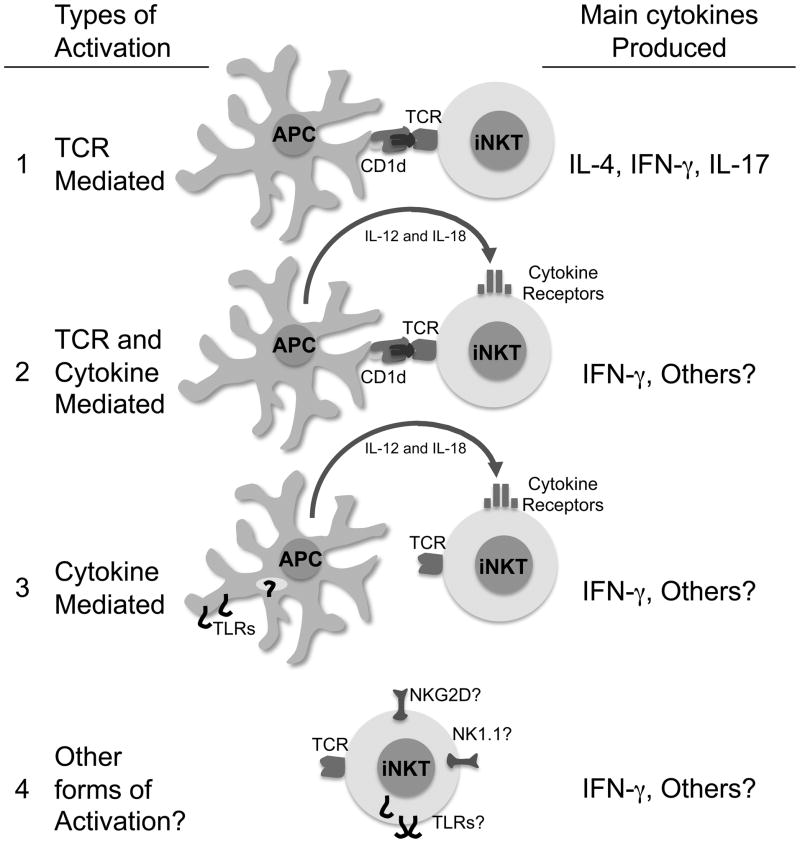

iNKT cells are unique T cells that can respond within minutes to specific Ag. Classical activation of iNKT cells is mediated through TCR recognition of a CD1d presented glycolipid (Fig. 1). Most of the initial investigations used the strong and prototypical agonist α-GalCer [3, 5]. Using CD1d deficient mice, it was demonstrated unequivocally that CD1d is critical for the presentation of α-GalCer to iNKT cells. Many studies subsequently utilized α-GalCer to determine the specific requirements needed for optimal iNKT cell activation. Additionally, the roles of several cytokines essential for activation of classical T cells such as IL-12, IL-18 and IFN-α were investigated. Due to the fact that downstream NK cell activation is dependent on these cytokines, there was initially some confusion regarding their roles in stimulating NKT cells. Most of the in vivo and in vitro data clearly indicate however that initial iNKT cell activation is mostly independent of these cytokines. Indeed, essential tools such as CD1d tetramer allowed investigators to discriminate between iNKT cells and NK cells to specifically demonstrate that inflammatory cytokines as well as co-stimulatory molecules were dispensable in this context [17, 18]. Other investigators using soluble CD1d coated on a plate showed in vitro that agonist glycolipids bound on CD1d were sufficient to activate iNKT cells [3]. These findings were physiologically confirmed with several recently identified microbial glycolipids from α-proteobacteria, such as Sphingomonas, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, as well as Borrelia. These agonist glycolipids can directly activate iNKT cells [13–16] independently of TLR or IL-12. Similarly to α-GalCer, the Sphingomonas glycolipids have been shown to induce the release of IFN-γ and IL-4 [13]. However, it has been shown that dendritic cells pulsed with α-GalCer or Sphingomonas glycolipids preferentially stimulate the production of IFN-γ rather than IL-4 [13, 19].

Figure 1.

iNKT cell activation pathways

This and other findings led to the development of glycolipid analogs and strategies to polarize iNKT responses [20–23]. Polarization of the iNKT cell response has been observed using α-GalCer analogs, however the mechanism leading to this polarization is still under intense investigation [24–26]. Regardless of the mechanism(s), it was recently shown that although TH1 and TH2 α-GalCer analogs can induce the predicted systemic cytokine bias, the immediate iNKT cell response is not polarized [27]. Importantly, direct iNKT cell activation with analogs is not without consequences, as overstimulation of iNKT cells can result in iNKT-cell anergy [28, 29].

1.1 Subset of iNKT cells activated during this pathway

iNKT cells have been subdivided into several subsets based on cell surface marker expression. Analysis of these subsets demonstrated they do not respond identically to a stimulus. For instance when stimulated by α-GalCer, human CD4+ iNKT cells produce both TH1 and TH2 cytokines, whereas CD4−(mostly double negative) iNKT cells produce mainly TH1 cytokines [30, 31]. Notably, this dichotomy has not been observed in the mouse. Whether this difference in cytokine production exists in response to α-proteobacteria derived iNKT cell agonists has yet to be determined.

Other subsets of iNKT cells have been recently characterized. These include a distinct IL-17-producing cell subset [32, 33], termed iNKT17 cells, as well as a subset that expresses the IL-25R [34]. iNKT17 cells differ from their classical counterpart by lack of NK1.1 expression, presence of ROR-γt which is essential for their alternative developmental program, and their prevalence in the peripheral lymph nodes [35]. NK1.1 negative iNKT cells produce IL-17 upon recognition of exogenous glycolipids derived from Sphingomonas wittichii and Borrelia burgdorferi [33] as well as by direct cross-link of CD3 and CD28 [36], suggesting that engagement of the invariant TCR is sufficient to stimulate iNKT17 cells.

2. TCR and cytokine mediated activation

Bacteria such as Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis that lack agonist glycolipids have been reported to activate iNKT cells through recognition of endogenous lysosomal glycosphingolipids, presented by pathogen-activated dendritic cells [14, 37–39]. The identification of the CD1d self-Ag promoting iNKT cell autoreactivity during inflammation has been actively pursued (for review see [40]). Among self-lipids, isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) [41], lysophosphatidylcholine [42], and phosphatidylcholine [43] have been identified as potential candidates. Although the role of the self-glycolipid iGb3 presented by CD1d has been challenged [44–46], the contribution of both CD1d and cytokines in this pathway has been clearly established for both mouse and human iNKT cells [14, 37–39].

Importantly, this pathway (Fig. 1) has been observed not only in bacteria but also in the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Interestingly, a role for TLRs has been demonstrated for Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus [14, 37] but not for Trypanosoma cruzi [47]. Alternatively, a role for IL-18 has been shown in the case of Mycobacterium tuberculosis [48].

During this pathway, regardless of the differences observed between pathogens, the inflammatory cytokine IL-12 has been detected in the majority of the cases. Therefore, and not surprisingly, iNKT cells have been found to secrete primarily IFN-γ. However, a recent study reported that human CD4+ iNKT cell clones could selectively produce copious amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 when cultured with CD1d+ APCs in the presence of IL-2 or IL-15 [49]. These observations suggest that the inflammatory milieu could influence iNKT cell polarization during the indirect recognition of pathogens.

2.1 Subset of iNKT cells activated during this pathway

Stimulation with the endogenous glycolipid iGb3 results in comparable IFN-γ secretion from CD4+ and double negative iNKT cells [41]. Given the role of endogenous glycolipids in this pathway, it suggests that these two subsets respond similarly. However, this has not been formally tested during infection with bacteria that lack agonist glycolipids. Notably, Sakuishi et al demonstrated that CD4 positive but not double negative iNKT cells produce IL-5 in response to IL-2 and dendritic cell stimulation [49].

3. Cytokine mediated activation

iNKT cells express several cytokine receptors (Fig. 1). In contrast to naive T cells, iNKT cells constitutively contain cytokine transcripts that correlate with chromatin modifications at the respective cytokine loci and have the capacity for rapid cytokine production [50]. Therefore it was likely that cytokines such as IL-12 and IL-18 would induce iNKT cell cytokine release in the absence of TCR engagement. Several studies have found that iNKT cells release INF-γ when stimulated by IL-12 and IL-18 supporting a possible strict NK-like cell role for iNKT cells in some contexts [51–53]. These findings were recently physiologically confirmed during viral infection. During MCMV infection, iNKT cells display signs of activation, up-regulation of the receptor CD25, a decrease in cell numbers in the spleen and liver and a robust production of IFN-γ [54, 55]. Blocking the invariant TCR recognition with anti-CD1d Abs or iNKT cell adoptive transfer into CD1d−/− hosts demonstrated a dispensable role for CD1d in this context. However, while the TCR engagement was not critical to the outcome, IFN-γ production was shown to be at least partially dependent on IL-12 and IFNα̃β secretion [54]. Mechanistically, it was found that MCMV elicits the activation of DCs in a TLR9 dependent fashion, stimulating the production of IL-12, which subsequently activates the iNKT cells to produce IFN-γ [55]. MCMV infection of TLR9 mutant mice did not result in a marked activation of iNKT cells suggesting an essential role for TLR9 in this pathway [55]. Two recent studies corroborate the MCMV findings and show that CpG induced activation of iNKT cells is mostly dependent on IL-12 with a minimal role for CD1d [55, 56]. Alternatively, when bone marrow derived cells were used, a role for CD1d was found during CpG induced iNKT cell activation [39]. LPS, another TLR ligand also shows CD1d dependence in some instances, [37] but not in others [57]. Overall, the results demonstrate that iNKT cells can respond effectively to several pathogens with limited TCR involvement.

Recent studies have addressed the role of IL-33 in promoting activation of iNKT cells in both humans and murine models. A member of the interleukin-1 family, IL-33 is a relative newcomer to well studied cytokines. IL-33 was initially identified as the ligand for the T1/ST2 receptor, which is present on mast cells and TH2 effector T cells. IL-33 increases the production of IFN-γ by iNKT cells in the presence of α-GalCer [58]. Interestingly, in the absence of TCR engagement, but in cooperation with IL-12, IL-33 can induce IFN-γ production from iNKT cells [58].

3.1 Subset of iNKT cells activated during this pathway

In response to MCMV, approximately 40% of the liver and splenic iNKT cells produce IFN-γ. Interestingly, in this context, CD4+ and double negative iNKT cell populations produce comparable levels of IFNγ (Reilly & Brossay, data not shown). The contribution of iNKT17 cells during viral infection has been recently examined. Stout-Delgado et al recently identified IL-17 producing iNKT cells in aged mice infected with Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2) or MCMV, which contribute significantly to liver damage and mortality [59]. However, it is not known if the IL-17 production by iNKT cells in infected aged animals requires direct TCR stimulation. Interestingly, it was found that iNKT17 cells produce IL-17 in response to LPS in vivo [33]. Because CD1d is not always required during LPS induced activation of iNKT cells (as discussed above), it is possible that iNKT17 cells respond to stimuli in the absence of TCR engagement. In support of this possibility, iNKT17 cells constitutively express the IL-23 receptor and can produce IL-17 in the presence of IL-23 [60]. Another unique iNKT cell subset has been shown to respond to IL-25 but only in the presence of CD1d+ APC suggesting a role for CD1d [34, 61].

4. Other mechanisms of activation: NK receptors and TLR

There have been studies that report TLR expression by iNKT cells, including intracellular TLR9 [62–64] and TLR3 [65]. However, it has not been clearly defined whether these TLRs are functional and if their ligands can directly activate iNKT cells. In fact in humans, direct iNKT cell stimulation with TLR4 or TLR7/8 ligands has not been observed [38].

NK1.1 cross-linking has been reported to directly activate mouse iNKT cells [66] but this phenomenon was not observed in humans when CD161 was cross-linked [67]. NKG2D, an activating receptor that recognizes stress-induced molecules and can trigger cytolytic activity, is also expressed on iNKT cells. In humans, double negative iNKT cells preferentially express NKG2D whereas in the mouse it is primarily expressed on NK1.1 positive iNKT cells [30, 68]. Interestingly, blocking NKG2D on non-classical CD1d restricted NKT cells decreases the detrimental effects caused by Hepatitis B virus [69].

5. Concluding remarks

iNKT cells comprise a diverse population with traits of both innate and adaptive cells. Strategies to polarize iNKT cells have been investigated. Polarization of the iNKT cell response has been observed using α-GalCer analogs, however the mechanism leading to this polarization is still under intense investigation [24–26]. Notably, it has been recently shown that combined iNKT cell activation and influenza virus vaccination boosts memory CTL generation and protective immunity [70]. However, administration of a strong agonist such as α-GalCer can cause iNKT cells to become unresponsive, raising the issue of anergy induction in designing treatment regimens that use specific activators of iNKT cells [28, 71]. Understanding the different mechanisms of iNKT cell activation will help to develop better strategies utilizing iNKT properties in the design of adjuvants or vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Research Grants AI46709 to LB and AA-08169 to JRW. Emma Reilly is supported by a NIH Ruth Kirschstein Individual Training Award (T32 DK60415-05).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nri854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD1: Antigen Presentation and T Cell Function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:817–890. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kronenberg M. Toward an Understanding of NKT Cell Biology: Progress and Paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfrey DI, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Smyth MJ, Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what’s in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:231–7. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The Biology of NKT Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, Nakagawa R, Sato H, Kondo E, Koseki H, Taniguchi M. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of Va14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdin N, Brossay L, Koezuka Y, Smiley ST, Grusby MJ, Gui M, Taniguchi M, Hayakawa K, Kronenberg M. Selective ability of mouse CD1 to present glycolipids: a-galactosylceramide specifically stimulates Va14+ NK T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:3271–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benlagha K, Weiss A, Beavis A, Teyton L, Bendelac A. In vivo identification of glycolipid antigen-specific T cells using fluorescent CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1895–903. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuda JL, Naidenko OV, Gapin L, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Wang CR, Koezuka Y, Kronenberg M. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;192:741–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smiley ST, Kaplan MH, Grusby MJ. Immunoglobulin E production in the absence of interleukin-4-secreting CD1-dependent cells. Science. 1997;275:977–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YH, Chiu NM, Mandal M, Wang N, Wang CR. Impaired NK1+ T cell development and early IL-4 production in CD1-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:459–67. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendiratta SK, Martin WD, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–477. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinjo Y, Wu D, Kim G, Xing GW, Poles MA, Ho DD, Tsuji M, Kawahara K, Wong CH, Kronenberg M. Recognition of bacterial glycosphingolipids by natural killer T cells. Nature. 2005;434:520–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattner J, Debord KL, Ismail N, Goff RD, Cantu C, 3rd, Zhou D, Saint-Mezard P, Wang V, Gao Y, Yin N, Hoebe K, Schneewind O, Walker D, Beutler B, Teyton L, Savage PB, Bendelac A. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature. 2005;434:525–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sriram V, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Brutkiewicz RR. Cell wall glycosphingolipids of Sphingomonas paucimobilis are CD1d-specific ligands for NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1692–701. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinjo Y, Tupin E, Wu D, Fujio M, Garcia-Navarro R, Benhnia MR, Zajonc DM, Ben-Menachem G, Ainge GD, Painter GF, Khurana A, Hoebe K, Behar SM, Beutler B, Wilson IA, Tsuji M, Sellati TJ, Wong CH, Kronenberg M. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:978–86. doi: 10.1038/ni1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Baron JL, Sidobre S, Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Locksley RM, Kronenberg M. Mouse Va14i natural killer T cells are resistant to cytokine polarization in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8395–8400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332805100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wesley JD, Robbins SH, Sidobre S, Kronenberg M, Terrizzi S, Brossay L. Cutting edge: IFN-gamma signaling to macrophages is required for optimal Valpha14i NK T/NK cell crosstalk. J Immunol. 2005;174:3864–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Kronenberg M, Steinman RM. Prolonged IFN-g-producing NKT response induced with a-galactosylceramide-loaded DCs. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:867–874. doi: 10.1038/ni827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto K, Miyake S, Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature. 2001;413:531–534. doi: 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oki S, Chiba A, Yamamura T, Miyake S. The clinical implication and molecular mechanism of preferential IL-4 production by modified glycolipid-stimulated NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1631–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI20862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu KO, Im JS, Molano A, Dutronc Y, Illarionov PA, Forestier C, Fujiwara N, Arias I, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Chang YT, Besra GS, Porcelli SA. Modulation of CD1d-restricted NKT cell responses by using N-acyl variants of alpha-galactosylceramides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3383–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407488102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmieg J, Yang G, Franck RW, Tsuji M. Superior protection against malaria and melanoma metastases by a C-glycoside analogue of the natural killer T cell ligand alpha-Galactosylceramide. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1631–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanic AK, Shashidharamurthy R, Bezbradica JS, Matsuki N, Yoshimura Y, Miyake S, Choi EY, Schell TD, Van Kaer L, Tevethia SS, Roopenian DC, Yamamura T, Joyce S. Another view of T cell antigen recognition: cooperative engagement of glycolipid antigens by Va14Ja18 natural T(iNKT) cell receptor [corrected] J Immunol. 2003;171:4539–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oki S, Tomi C, Yamamura T, Miyake S. Preferential T(h)2 polarization by OCH is supported by incompetent NKT cell induction of CD40L and following production of inflammatory cytokines by bystander cells in vivo. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1619–29. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Im JS, Arora P, Bricard G, Molano A, Venkataswamy MM, Baine I, Jerud ES, Goldberg MF, Baena A, Yu KO, Ndonye RM, Howell AR, Yuan W, Cresswell P, Chang YT, Illarionov PA, Besra GS, Porcelli SA. Kinetics and cellular site of glycolipid loading control the outcome of natural killer T cell activation. Immunity. 2009;30:888–98. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan BA, Nagarajan NA, Wingender G, Wang J, Scott I, Tsuji M, Franck RW, Porcelli SA, Zajonc DM, Kronenberg M. Mechanisms for glycolipid antigen-driven cytokine polarization by Valpha14i NKT cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:141–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Singh AK, Wu L, Wang CR, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2572–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim S, Lalani S, Parekh VV, Vincent TL, Wu L, Van Kaer L. Impact of bacteria on the phenotype, functions, and therapeutic activities of invariant NKT cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2301–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI33071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gumperz JE, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Brenner MB. Functionally distinct subsets of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells revealed by CD1d tetramer staining. J Exp Med. 2002;195:625–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee PT, Benlagha K, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Distinct functional lineages of human V(alpha)24 natural killer T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:637–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michel ML, Mendes-da-Cruz D, Keller AC, Lochner M, Schneider E, Dy M, Eberl G, Leite-de-Moraes MC. Critical role of ROR-gammat in a new thymic pathway leading to IL-17-producing invariant NKT cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19845–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806472105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michel ML, Keller AC, Paget C, Fujio M, Trottein F, Savage PB, Wong CH, Schneider E, Dy M, Leite-de-Moraes MC. Identification of an IL-17-producing NK1.1(neg) iNKT cell population involved in airway neutrophilia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:995–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terashima A, Watarai H, Inoue S, Sekine E, Nakagawa R, Hase K, Iwamura C, Nakajima H, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M. A novel subset of mouse NKT cells bearing the IL-17 receptor B responds to IL-25 and contributes to airway hyperreactivity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2727–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doisne JM, Becourt C, Amniai L, Duarte N, Le Luduec JB, Eberl G, Benlagha K. Skin and peripheral lymph node invariant NKT cells are mainly retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor (gamma)t+ and respond preferentially under inflammatory conditions. J Immunol. 2009;183:2142–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coquet JM, Chakravarti S, Kyparissoudis K, McNab FW, Pitt LA, McKenzie BS, Berzins SP, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. Diverse cytokine production by NKT cell subsets and identification of an IL-17-producing CD4-NK1.1- NKT cell population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801631105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1230–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salio M, Speak AO, Shepherd D, Polzella P, Illarionov PA, Veerapen N, Besra GS, Platt FM, Cerundolo V. Modulation of human natural killer T cell ligands on TLR-mediated antigen-presenting cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20490–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710145104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paget C, Mallevaey T, Speak AO, Torres D, Fontaine J, Sheehan KC, Capron M, Ryffel B, Faveeuw C, Leite de Moraes M, Platt F, Trottein F. Activation of invariant NKT cells by toll-like receptor 9-stimulated dendritic cells requires type I interferon and charged glycosphingolipids. Immunity. 2007;27:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brutkiewicz RR. CD1d ligands: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Immunol. 2006;177:769–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou D, Mattner J, Cantu C, 3rd, Schrantz N, Yin N, Gao Y, Sagiv Y, Hudspeth K, Wu YP, Yamashita T, Teneberg S, Wang D, Proia RL, Levery SB, Savage PB, Teyton L, Bendelac A. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306:1786–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fox LM, Cox DG, Lockridge JL, Wang X, Chen X, Scharf L, Trott DL, Ndonye RM, Veerapen N, Besra GS, Howell AR, Cook ME, Adams EJ, Hildebrand WH, Gumperz JE. Recognition of lyso-phospholipids by human natural killer T lymphocytes. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan W, Kang S-J, Evans JE, Cresswell P. Natural Lipid Ligands Associated with Human CD1d Targeted to Different Subcellular Compartments. J Immunol. 2009;182:4784–4791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Speak AO, Salio M, Neville DC, Fontaine J, Priestman DA, Platt N, Heare T, Butters TD, Dwek RA, Trottein F, Exley MA, Cerundolo V, Platt FM. From the Cover: Implications for invariant natural killer T cell ligands due to the restricted presence of isoglobotrihexosylceramide in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5971–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607285104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Porubsky S, Speak AO, Luckow B, Cerundolo V, Platt FM, Grone HJ. From the Cover: Normal development and function of invariant natural killer T cells in mice with isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5977–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611139104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Christiansen D, Milland J, Mouhtouris E, Vaughan H, Pellicci DG, McConville MJ, Godfrey DI, Sandrin MS. Humans lack iGb3 due to the absence of functional iGb3-synthase: implications for NKT cell development and transplantation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duthie MS, Kahn M, White M, Kapur RP, Kahn SJ. Both CD1d antigen presentation and interleukin-12 are required to activate natural killer T cells during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1890–4. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1890-1894.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sada-Ovalle I, Chiba A, Gonzales A, Brenner MB, Behar SM. Innate invariant NKT cells recognize Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages, produce interferon-gamma, and kill intracellular bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000239. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sakuishi K, Oki S, Araki M, Porcelli SA, Miyake S, Yamamura T. Invariant NKT Cells Biased for IL-5 Production Act as Crucial Regulators of Inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:3452–3462. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stetson DB, Mohrs M, Reinhardt RL, Baron JL, Wang ZE, Gapin L, Kronenberg M, Locksley RM. Constitutive cytokine mRNAs mark natural killer (NK) and NK T cells poised for rapid effector function. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1069–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leite-De-Moraes MC, Hameg A, Arnould A, Machavoine F, Koezuka Y, Schneider E, Herbelin A, Dy M. A distinct IL-18-induced pathway to fully activate NK T lymphocytes independently from TCR engagement. J Immunol. 1999;163:5871–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eberl G, MacDonald HR. Rapid death and regeneration of NKT cells in anti-CD3epsilon-or IL-12-treated mice: a major role for bone marrow in NKT cell homeostasis. Immunity. 1998;9:345–53. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80617-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Park SH, Kyin T, Bendelac A, Carnaud C. The contribution of NKT cells, NK cells, and other gamma-chain-dependent non-T non-B cells to IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. J Immunol. 2003;170:1197–201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wesley JD, Tessmer MS, Chaukos D, Brossay L. NK cell-like behavior of Valpha14i NK T cells during MCMV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000106. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyznik AJ, Tupin E, Nagarajan NA, Her MJ, Benedict CA, Kronenberg M. Cutting edge: the mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. J Immunol. 2008;181:4452–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paget C, Bialecki E, Fontaine J, Vendeville C, Mallevaey T, Faveeuw C, Trottein F. Role of invariant NK T lymphocytes in immune responses to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2009;182:1846–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagarajan NA, Kronenberg M. Invariant NKT cells amplify the innate immune response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2007;178:2706–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bourgeois E, Van LP, Samson M, Diem S, Barra A, Roga S, Gombert JM, Schneider E, Dy M, Gourdy P, Girard JP, Herbelin A. The pro-Th2 cytokine IL-33 directly interacts with invariant NKT and NK cells to induce IFN-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1046–55. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stout-Delgado HW, Du W, Shirali AC, Booth CJ, Goldstein DR. Aging promotes neutrophil-induced mortality by augmenting IL-17 production during viral infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:446–56. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rachitskaya AV, Hansen AM, Horai R, Li Z, Villasmil R, Luger D, Nussenblatt RB, Caspi RR. Cutting Edge: NKT Cells Constitutively Express IL-23 Receptor and ROR{gamma}t and Rapidly Produce IL-17 upon Receptor Ligation in an IL-6-Independent Fashion. J Immunol. 2008;180:5167–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stock P, Lombardi V, Kohlrautz V, Akbari O. Induction of Airway Hyperreactivity by IL-25 Is Dependent on a Subset of Invariant NKT Cells Expressing IL-17RB. J Immunol. 2009;182:5116–5122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimizu H, Matsuguchi T, Fukuda Y, Nakano I, Hayakawa T, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Umemura M, Suda T, Yoshikai Y. Toll-like receptor 2 contributes to liver injury by Salmonella infection through Fas ligand expression on NKT cells in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1265–77. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takashi H, Tetsuya M, Hideyuki S, Toshiki Y, Hitoshi N, Toshiyuki A, Yuji N, Yasunobu Y. NK T cells stimulated with a ligand for TLR2 at least partly contribute to liver injury caused by Escherichia coli infection in mice. European Journal of Immunology. 2003;33:2511–2519. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Askenase PW, Itakura A, Leite-de-Moraes MC, Lisbonne M, Roongapinun S, Goldstein DR, Szczepanik M. TLR-Dependent IL-4 Production by Invariant V{alpha}14+J{alpha}18+ NKT Cells to Initiate Contact Sensitivity In Vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:6390–6401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gardner TR, Chen Q, Jin Y, Ajuebor MN. Toll-like receptor 3 ligand dampens liver inflammation by stimulating Valpha 14 invariant natural killer T cells to negatively regulate gammadeltaT cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1779–89. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arase H, Arase N, Saito T. Interferon gamma production by natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1+ T cells upon NKR-P1 cross-linking. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2391–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Exley M, Porcelli S, Furman M, Garcia J, Balk S. CD161 (NKR-P1A) Costimulation of CD1d-dependent Activation of Human T Cells Expressing Invariant V{alpha}24J{alpha}Q T Cell Receptor {alpha} Chains. J Exp Med. 1998;188:867–876. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.5.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McNab FW, Pellicci DG, Field K, Besra G, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Peripheral NK1.1 NKT Cells Are Mature and Functionally Distinct from Their Thymic Counterparts. J Immunol. 2007;179:6630–6637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baron JL, Gardiner L, Nishimura S, Shinkai K, Locksley R, Ganem D. Activation of a nonclassical NKT cell subset in a transgenic mouse model of hepatitis B virus infection. Immunity. 2002;16:583–94. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guillonneau C, Mintern JD, Hubert Fo-X, Hurt AC, Besra GS, Porcelli S, Barr IG, Doherty PC, Godfrey DI, Turner SJ. Combined NKT cell activation and influenza virus vaccination boosts memory CTL generation and protective immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:3330–3335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813309106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sullivan BA, Kronenberg M. Activation or anergy: NKT cells are stunned by alpha-galactosylceramide. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2328–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI26297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]