Abstract

Objective

The 2009 pandemic of influenza A/H1N1 has disproportionately affected children and young adults, resulting in attention by public health officials and the news media on schools as important settings for disease transmission and spread. We aimed to characterize US schools affected by novel influenza A/H1N1 relative to other schools in the same communities.

Methods

A database of US school-related cases was obtained by electronic news media monitoring for early reports of novel H1N1 influenza between April 23 and June 8, 2009. We performed a matched case-control study of 32 public primary and secondary schools that had one or more confirmed cases of H1N1 influenza and 6815 control schools located in the same 23 counties as case schools.

Results

Compared with controls from the same county, schools with reports of confirmed cases of H1N1 influenza were less likely to have a high proportion of economically disadvantaged students (adjusted OR, 0.385; 95% CI, 0.166 – 0.894) and less likely to have older students (adjusted OR, 0.792; 95% CI, 0.670 – 0.938).

Conclusions

We conclude that public schools with younger, more affluent students may be considered sentinels of the epidemic and may have played a role in its initial spread.

Keywords: Influenza A/H1N1, HealthMap, schools, age, socio-economic status

Introduction

One striking feature of the 2009 pandemic of novel influenza A/H1N1 has been the skewed age distribution of confirmed cases, with children and young adults disproportionately affected.1 Early clinical evidence revealed a shift in the age distribution, with the majority of deaths and severe cases being patients between the ages of 5 and 59, and especially children.2–4 Possible explanations for this pattern of infection include preexisting immunity in older age groups and an important role for schools as settings for the early outbreaks of the pandemic.1, 5

We monitored in real-time the early school-related outbreaks of novel H1N1 influenza in the United States using the event-based HealthMap disease surveillance platform.6–8 HealthMap monitors informal web-based media reports, moderated distribution lists such as ProMED Mail, and official public health agency alerts for disease outbreak information. We analyzed early media reports collected by HealthMap for information on novel H1N1 influenza outbreaks in schools in order to build an early epidemiological picture of the novel H1N1 epidemic in US public schools.9

Methods

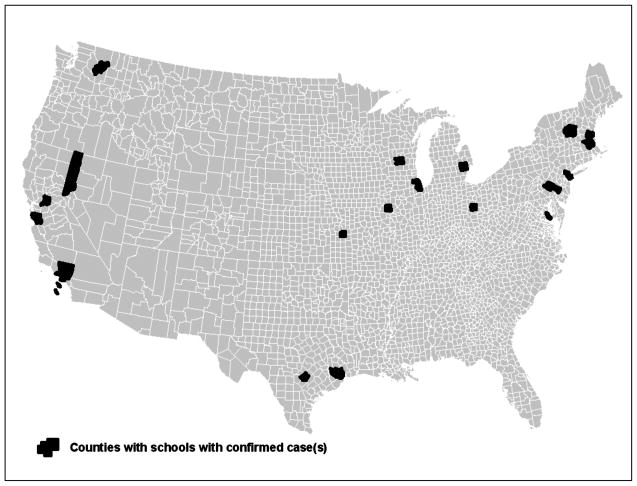

Between April 23 and June 8, 2009, HealthMap detected 181 English-language media reports related to suspected or confirmed cases of novel H1N1 influenza in schools and universities worldwide. We filtered these reports to examine more closely public primary and secondary schools in the US with one or more confirmed cases of novel H1N1 influenza, resulting in 49 reports referring to 32 individual schools in 23 US counties (figure).

Figure.

Map of counties with schools with one or more confirmed cases of H1N1 influenza detected by HealthMap

We were interested in identifying characteristics of schools impacted by H1N1 influenza. Using data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), we examined the features of US public primary and secondary schools with confirmed cases relative to other schools in the same communities. Data were obtained from the NCES for each of the schools with a media report of novel H1N1 cases as well as for all of the other schools in the counties in which the schools in our dataset were located. The resulting database included 32 schools with one or more media reports detected by HealthMap and 6815 nearby control schools with no media reports detected by HealthMap. By comparing schools with confirmed cases to other schools in the same communities, we aimed to avoid sampling bias due to inconsistent media coverage across communities as well as confounding due to geography.

We examined relationships between the probability of one or more confirmed cases of novel H1N1 influenza and several characteristics of schools: highest and lowest grade levels at the school, indicating the age groups present at the school; grade span, or number of grades at the school; student-to-teacher ratio; whether or not the school qualifies for funding under Title 1, a program that provides federal assistance to schools to support economically disadvantaged students, a socioeconomic indicator; whether or not the school is located within an “urbanized area” as defined by the US Census Bureau;10 the proportion of students belonging to four racial/ethnic groups: Hispanic, White, Black and Asian; and racial/ethnic diversity, measured using Simpson’s Index of diversity, D,11 which was calculated using the following formula:

where N is the total number of students in the school and n is the number of students of each racial/ethnic group in the school.

We used a backward elimination model selection procedure to build a multivariate model to estimate the probability of a school having one or more confirmed cases detected by HealthMap. The number of students enrolled in the school was log-transformed and included in all models to account for the probability of one or more confirmed cases as a function of student body size. Because schools with media reports were matched to control schools within the same county, we used conditional logistic regression in both univariate and multivariate models to account for within-county dependence. The R Statistical System (version 2.7.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org) was used for all statistical computations.

Results

Relationships between school characteristics and media reports of H1N1 are presented in the table. The final multivariate model revealed independent significant relationships with number of students, highest grade level and Title 1 status. As expected, schools with more students were more likely to have been reported as having one or more confirmed cases of novel H1N1 influenza. In addition, schools with lower maximum grade levels (in general, primary schools) and schools not qualifying for Title 1 funding (schools with fewer economically disadvantaged students) were more likely than other schools in the same county to have been detected. Lowest grade level, grade span, student-to-teacher ratio, the urbanized area-indicator and the variables relating to racial/ethnic makeup of schools were dropped from the final multivariate model. Overall, this analysis suggests that within affected counties, affluent schools with a younger student body are more likely than other schools in the same community to have confirmed cases of novel H1N1 influenza that are picked up by the media and detected by HealthMap.

Table.

| Mean ± SD | Univariate Models | Final Multivariate Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Schools with one or more cases (N=32) | Other schools in county (N=6815) | OR* (95% CI†) | P | Adjusted OR* (95% CI†) | P |

| Student Body Size | 945.22 ± 677.21 | 704.10 ± 618.54 | 3.759 (2.158, 6.547) | <0.001 | 7.344 (3.100, 17.398) | <0.001 |

| Lowest Grade at School | 3.38 ± 4.19 | 2.42 ± 3.81 | 0.929 (0.832, 1.036) | 0.185 | -- | -- |

| Highest Grade at School | 7.53 ± 3.20 | 7.16 ± 2.93 | 0.828 (0.703, 0.975) | 0.024 | 0.792 (0.670, 0.938) | 0.007 |

| Grade Span | 4.16 ± 2.38 | 4.74 ± 2.33 | 0.961 (0.881, 1.153) | 0.671 | -- | -- |

| Student-Teacher Ratio | 16.08 ± 3.45 | 17.28 ± 4.98 | 0.991 (0.872, 1.126) | 0.893 | -- | -- |

| Title 1 School (%) | 14(43.8) | 4694(68.9) | 0.525 (0.234, 1.178) | 0.118 | 0.385 (0.166, 0.894) | 0.025 |

| Located in Urbanized Area (%) | 24(75.0) | 6311(92.6) | 1.697 (0.340, 8.463) | 0.519 | -- | -- |

| Proportion Hispanic Students | 0.13 ± 0.21 | 0.37 ± 0.32 | 0.180 (0.013, 2.467) | 0.199 | -- | -- |

| Proportion White Students | 0.55 ± 0.35 | 0.31 ± 0.32 | 4.611 (0.627, 33.894) | 0.133 | -- | -- |

| Proportion Black Students | 0.09 ± 0.19 | 0.19 ± 0.27 | 0.154 (0.008, 2.897) | 0.211 | -- | -- |

| Proportion Asian Students | 0.23 ± 0.32 | 0.12 ± 0.18 | 0.939 (0.042, 21.204) | 0.533 | -- | -- |

| Racial/Ethnic Diversity | 0.32 ± 0.20 | 0.40 ± 0.21 | 0.450 (0.033, 6.000) | 0.546 | -- | -- |

OR, Odds ratio;

CI, Confidence interval

Conclusions

We have presented an initial characterization of the US public schools affected by the recent novel H1N1 influenza outbreak using a real-time, informal surveillance system, HealthMap. While there is no tool for monitoring outbreaks of this nature in the US that is without detection biases, there are some limitations specific to our approach. Namely, we were limited not only by the ability of public health officials to detect and confirm cases, but also by the ability and willingness of the media to report them. This was less of an issue in the early stages of the epidemic, when both sectors were actively investigating outbreaks, and for this reason we limited our analysis to the earliest news reports. Detailed evaluation of the utility of these data sources remains an important research question. However, our approach allowed us to quickly detect and catalog, in real-time, outbreaks of novel H1N1 influenza in schools that, to our knowledge, were not otherwise formally documented at this scale. Influenza transmission in schools is not reportable to the state or federal governments, making the news media a potentially more sensitive and timely data source then the currently voluntary systems in place.

We compared schools that were reported to have experienced outbreaks of novel H1N1 influenza with nearby schools that were not, and we have presented an initial investigation of school characteristics associated with such reporting. Our observation that schools with lower grade levels were likely to have an early case report detected by HealthMap is consistent with previous reports implicating the younger pediatric age groups as early sentinels of seasonal influenza epidemics.12 However, it is not entirely clear why more affluent schools with lower grade levels were more likely than other schools in the same county to report cases. Given the relatively mild clinical outcomes of the first cases, it could be that students attending these schools were more likely than others to have their illness diagnosed by a physician and thus reported as confirmed cases, or that these schools were more likely to receive media coverage when a case was detected. Because many of the first school-related cases of the epidemic were the result of students with travel histories to Mexico, it is also possible that these schools were more likely to have students that had recently travelled to Mexico. It is unclear whether the characteristics of schools identified represent actual risk factors for infection, or whether they characterize schools that may be most sensitive to case detection and media reporting. Nonetheless, the novel influenza A/H1N1 influenza pandemic has illustrated the importance of understanding the best targets for surveillance efforts to allow for early, sensitive, and accurate outbreak detection. Informal, event-based disease surveillance tools such as HealthMap and others hold promise as useful technologies that enable real-time assessments of epidemiological characteristics prior to the availability of such information through more traditional surveillance methods.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Amy Sonricker, Susan Aman, Rebecca F. Baggaley and T. Déirdre Hollingsworth for helpful discussions and computational support.

Funding Support

This work was supported by R21AI073591-01 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, PAN-83152 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a research grant from Google.org. CAD acknowledges the Medical Research Council, UK, for funding support.

Role of the Funding Sources

Neither the funding sources nor the sponsor played a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, nor the interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

Approval not required.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Peiris JS, Poon LL, Guan Y. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A virus (S-OIV) H1N1 virus in humans. J Clin Virol. 2009;45:169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowell G, Bertozzi SM, Colchero MA, Lopez-Gatell H, Alpuche-Aranda C, Hernandez M, et al. Severe respiratory disease concurrent with the circulation of H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med. 2009 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Cauchemez S, Hanage WP, Van Kerkhove MD, Hollingsworth TD, et al. Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): early findings. Science. 2009;324:1557–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1176062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishiura H, Castillo-Chavez C, Safan M, Chowell G. Transmission potential of the new influenza A(H1N1) virus and its age-specificity in Japan. Euro Surveill. 2009:14. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.22.19227-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Preliminary information important for understanding the evolving situation: pandemic (H1N1) briefing note 4. Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownstein JS, Freifeld CC, Reis BY, Mandl KD. Surveillance Sans Frontieres: Internet-based emerging infectious disease intelligence and the HealthMap project. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:E151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brownstein JS, Freifeld CC, Madoff LC. Influenza A (H1N1) virus, 2009--online monitoring. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freifeld CC, Mandl KD, Reis BY, Brownstein JS. HealthMap: global infectious disease monitoring through automated classification and visualization of Internet media reports. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:150–7. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller M, Blench M, Tolentino H, Freifeld CC, Mandl KD, Mawudeku A, et al. Use of unstructured event-based reports for global infectious disease surveillance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:689–95. doi: 10.3201/eid1505.081114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States. Bureau of the Census. Geographic areas reference manual. Washington, D.C: U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson EH. Measurement of diversity. Nature. 1949;163:1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownstein JS, Kleinman KP, Mandl KD. Identifying pediatric age groups for influenza vaccination using a real-time regional surveillance system. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:686–93. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]