Abstract

Trait abnormalities in bipolar disorder (BD) within ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) and amygdala suggest dysfunction in their connectivity. This study employed low frequency resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (LFRS-fMRI) to analyze functional connectivity between ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) and amygdala in BD. LFRS-fMRI identified a negative correlation in vPFC-amygdala activity, and the magnitude of this correlation was greater in healthy participants than in subjects with BD. Additionally, whole brain analysis revealed higher correlations between left and right vPFC in BD, as well as with ventral striatum.

Keywords: FMRI, bipolar disorder, prefrontal cortex, amygdala

1.Introduction

Previous functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of bipolar disorder (BD) demonstrate ventral prefrontal cortex (vPFC) and amygdala dysfunction (Altshuler et al., 2005; Blumberg et al., 2003a; Elliott et al., 2004; Ketter et al., 2001; Kronhaus et al., 2006; Kruger et al., 2003; Lawrence et al., 2004; Mah et al., 2007; Yurgelun-Todd et al., 2000), including simultaneously diminished vPFC and excessive amygdala response to emotional stimuli (Blumberg et al., 2003a; Foland et al., 2008a; Pavuluri et al., 2007). These studies implicate disruptions in inhibitory vPFC-amygdala connections that subserve affective regulation in this disorder. LFRS-fMRI provides measures of functional connectivity between brain regions consistent with their anatomic connectivity (Biswal et al., 1995; Hampson et al., 2002; Lowe et al., 1998; Raichle et al., 2001) and has been used successfully to demonstrate abnormal functional connectivity in mood disorders (Anand et al., 2009; Anand et al., 2005). We employed LFRS-fMRI to test the hypothesis activity in a left vPFC region associated with the BD trait (Blumberg et al., 2003a; Kronhaus et al., 2006) is negatively correlated with activity in the amygdala, and this vPFC-amygdala functional connectivity is diminished in BD.

2.Methods

2.1.Participants

Right handed subjects, ages 18-60 years old, and without major medical or neurological illness, were continuously recruited through medical centers affiliated with the Yale School of Medicine (YSM), New Haven, CT and the local community. They included 15 persons with BDI (ages=23-59 years; 7 female) and 10 healthy comparison (HC) subjects (ages=18-34 years, 4 female). Structured clinical interview (SCID) confirmed the presence or absence of Axis I disorders and mood state. Healthy participants did not have a personal history of an Axis I disorder or first-degree relative with an Axis I disorder. Subjects provided written informed consent as approved by the Yale School of Medicine and Veterans Affairs institutional review boards.

Clinical features of BD subjects included: 5 with rapid-cycling, 8 currently euthymic, 2 depressed and 5 in a mixed, manic or hypomanic state. Past co-morbidities included 1 with panic disorder, 1 with obsessive-compulsive disorder and 8 with alcohol/substance abuse/dependence in full-sustained remission (mean=10 years). Three were unmedicated at time of scanning, 5 were prescribed lithium salts, 7 anticonvulsants, 5 antipsychotics, 4 antidepressants and 2 benzodiazepines.

2.2.Image acquisition

Images were acquired with a GE 1.5 Tesla Signa LX scanner (General Electric Signa, Milwaukee, WI) equipped with a quadrature head coil and echoplanar capability. Ten 7mm axial-oblique T1-weighted spin-echo images with a variable skip of 1-2mm (Blumberg et al., 2003a) were acquired parallel to the anterior commissure-posterior commissure (AC-PC) plane (TR=500ms, TE=14ms, FOV=20cm×20cm, acquisition matrix=256×256). Using the same anatomic locations, functional images were acquired during 2 runs of 3min5sec using a T2*-sensitive gradient-recalled single shot echoplanar pulse sequence while subjects were at rest (TR=1650ms, TE=60ms, flip angle=60°, FOV=20cm × 20cm, acquisition matrix 64×64, voxel resolution=3.12mm × 3.12mm × 7mm).

2.3.Image processing

Images were motion corrected, normalized (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) and spatially-smoothed with a Gaussian filter (6.25mm full-width-at-half-maximum) using SPM99 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). The first 10 images in each run were discarded and echoplanar data filtered using a low-pass temporal filter (0.08Hz).

2.4.Data analysis

Data analysis was completed using locally designed software (Hampson et al., 2002). First, the left vPFC region of interest (ROI) was defined on a Talairach proportional grid system extending from coordinates x= −33mm to x= −17mm and y=53mm to y=35mm on a slice 4mm ventral to the AC-PC plane based on the region in which BD trait abnormalities were identified previously (Blumberg et al., 2003a). For each resting state run for a given subject, the mean time course for BOLD signal in the vPFC ROI was obtained by averaging across pixels in this ROI. The time course of the vPFC ROI was then partially correlated with the time course of each pixel in the brain, removing the effects of the mean global time course. The resulting correlation coefficients were transformed into z-scores (Lowe et al., 1998) and averaged across the two resting runs to create subject-specific maps of resting state correlations to the left vPFC. These maps were then combined across subjects within groups using pixel-wise 1-sample t-tests to produce group whole-brain composite maps. Contrast maps to assess between-group differences were then created using pixel-wise 2-sample (HC vs. BD) t-tests. For hypothesis-testing for the amygdala, correlations were considered significant for P<0.05 and cluster size>20 adjacent pixels (Forman et al., 1995). Monte Carlo simulation demonstrated that this cluster threshold was higher than the 11.4 adjacent pixels required to correct for multiple comparisons (AlphaSim, AFNI software library). Exploratory whole brain analyses were performed to identify additional vPFC-correlated regions that differed between the BD and HC group at a level of P<0.005, cluster size>20 pixels.

Post-hoc analyses were performed to assess potential effects of demographic and clinical variables on the correlation coefficients between left vPFC and regions where functional connectivity differed significantly between groups. Sex and age were analyzed in the whole group, and clinical factors analyzed in the BD group (including medication status, rapid-cycling, mood state at time of scan and history of alcohol/substance dependence).

3.Results

3.1.Demographics

There was no significant difference in sex distribution between the groups (P=0.74). Subjects with BD were significantly older than HC participants (mean ageHC=25yrs±SD5.8, meanBD=43±SD9.9; P<0.001); however, age did not have significant effects on vPFC-amygdala or left-right vPFC functional connectivity in either the whole group of subjects, or within the diagnostic subgroups (all P’s>0.60).

3.2.vPFC-amygdala functional connectivity

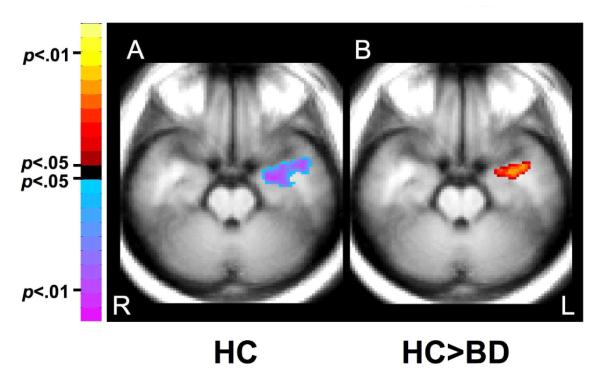

Significant negative correlation between activity in the left vPFC ROI and left amygdala was demonstrated in HC subjects (cluster=127 pixels, center-of-mass: x= −33.6mm, y= −4.7mm, z= −12mm, t=6.56) (Figure 1A). The strength of this negative correlation was lower in the BD relative to the HC group (cluster=56 pixels, center-of-mass: x= −31.9mm, y= −3.8mm, z= −12mm, t=2.45) (Figure 1B). These results survived cluster-level correction using Monte Carlo simulation.

Figure 1.

Functional Connectivity from a Left vPFC Region of Interest

The axial-oblique images demonstrate significant findings in which (A) resting state activity showed an inverse relationship between vPFC and amygdala in a HC group and (B) the strength of the negative correlation was significantly reduced in a group with BD compared to the healthy group. Note the left side of the brain is displayed on the right per radiological convention.

Abbreviations: vPFC, ventral prefrontal cortex; BD, Bipolar disorder; HC, Healthy Control; R, right; L, left

There were no significant effects of sex in the whole group, or of clinical features within the BD group, on vPFC-amygdala functional connectivity (all P’s>0.2).

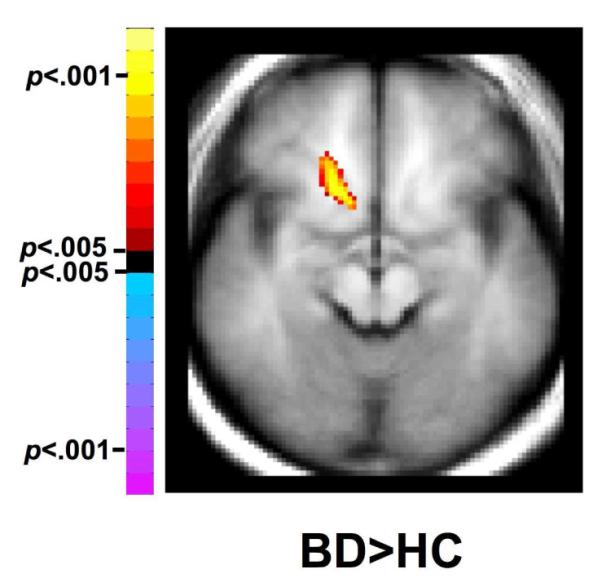

3.3.Whole brain analysis

This work revealed significant increases in inter-hemispheric correlations between the left vPFC ROI and right hemisphere in the BD relative to the HC group (cluster=56 pixels, center-of-mass: x=14.8mm, y= 19.4mm, z= −4mm, t=4.05) (Figure 2). This cluster extends from x=8 to 20mm, y=8 to 31mm and ventrally to z=−10mm. This cluster includes BA47, as well as BA 24/32 and ventral parts of the striatum (ventral caudate and putamen). The BD group also showed larger decreases in correlations between the left vPFC and dorsofrontal and parietal regions (z=32-40mm).

Figure 2.

Inter-hemispheric Functional Connectivity in Bipolar Disorder

The axial-oblique image demonstrates the right vPFC and ventral striatal regions in which there was significantly higher LFRS correlation with left vPFC in subjects with BD compared to HC subjects. Note the left side of the brain is displayed on the right per radiological convention.

Abbreviations: vPFC, ventral prefrontal cortex; BD, Bipolar disorder, HC, Healthy Control

There were no significant effects of sex in the whole group, or of clinical features within the BD group, on inter-hemispheric vPFC functional connectivity (all P’s>0.4).

4.Discussion

LFRS-fMRI analyses demonstrated a significant inverse relationship between left vPFC and amygdala activity in healthy subjects. The strength of this correlation was decreased in subjects with BD. This study also revealed significantly higher inter-hemispheric correlations between activity in left and right vPFC, and right ventral striatum in the BD subjects.

The observed decrease in LFRS-fMRI correlations between vPFC and amygdala in the BD group provides support for hypothesized reductions in their functional connectivity in this disorder. Evidence for increased inter-hemispheric correlations in BD suggests abnormalities in inter-hemispheric functional connectivity may contribute to affect dysregulation characteristic of this disorder. Hemispheric lateralization of processing of positive and negative emotions is evident in normal affective processing, and the balance between the hemispheres has been proposed to be important to adaptive affect regulation (Davidson, 2002). Evidence for abnormalities in hemispheric balance and inter-hemispheric functional connectivity in BD includes demonstration of lateralization of abnormalities in depressed and manic mood states, as well as impaired inter-hemispheric switching during perceptual processing (Blumberg et al., 2003a; Pettigrew and Miller, 1998). The presence of abnormal vPFC intra- and inter-hemispheric structural connectivity suggests that abnormalities in structural connectivity may contribute to the functional disruptions reported herein (Wang et al., 2008; Yurgelun-Todd et al., 2007). These findings may also reflect abnormalities in ventral striatum associated with BD (Blumberg et al., 2003b; Dickstein et al., 2007; Leibenluft et al., 2007; McIntosh et al., 2008) as well as potential disruptions in corticostriatal connectivity (Harrison et al., 2009).

The size of the subject sample and the complexity of the medication regimens of the BD subjects may limit interpretation of medication effects in this study. Research across several diagnostic groups suggest pharmacotherapy may modify regional brain activity and volume (Arce et al., 2008; Bell et al., 2005; Foland et al., 2008b; Greicius et al., 2008; Hollander et al., 2008; Kohno et al., 2007; Moresco et al., 2001). Although it is possible medication may have contributed to these findings, previous observations that pharmacotherapy can reduce vPFC and amygdala abnormalities in mood disorders suggest inclusion of medicated subjects might have reduced group differences (Anand et al., 2007; Anand et al., 2005; Blumberg et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2008; Dougherty and Rauch, 2007; Jogia et al., 2008; Lawrence et al., 2004; Ozerdem et al., 2008; Yurgelun-Todd et al., 2000). Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamatergic systems are among those implicated in modulation of the inhibitory relationship between vPFC and amygdala (Ghashghaei and Barbas, 2002; Northoff et al., 2007; Quirk et al., 2003), and mood-stabilizing pharmacotherapies have been theorized to exert their therapeutic effects by restoring the balance in these systems (Frye et al., 2007; Krystal et al., 2002). Future studies using larger samples and systematic study of specific medication classes are needed to more definitively assess medication effects on vPFC-amygdala connectivity in BD.

Resting state studies may better reflect the natural mental state of an individual compared to studies in which mental states are constrained by activation tasks (Raichle et al., 2001). An inability to control for subjects’ thoughts during imaging, however, is a limitation common to resting state studies. Despite this limitation, resting state fMRI studies have yielded reproducible results consistent with known anatomic connectivity (Biswal et al., 1995; Greicius et al., 2003). Time courses for cardiac and pulmonary fluctuations were not measured, though they could yield signal changes independent of neuronal function (Birn et al., 2006; Wise et al., 2004). Another potential limitation to this study includes the discrepancy in mean age between the subject groups; although analysis demonstrated no significant effects of age on any of the results. Given these limitations, these results should be considered preliminary and future studies of larger numbers of subjects, better balanced for age and taking into account these factors, are warranted.

In sum, our observations are consistent with literature demonstrating functional connections between vPFC and amygdala, and support a role for LFRS-fMRI analyses in studying this neural system in healthy and pathologic states. This method provided support for hypothesized decreases in vPFC-amygdala functional connectivity in BD and revealed dysregulated inter-hemispheric connectivity in the disorder. Future studies using LFRS-fMRI to evaluate the ability of medications to reverse impairments in vPFC-amygdala functional connectivity may yield new insights into the cortico-limbic system in BD pathology and suggest new treatment approaches.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Ms. Kathleen Colonese who was devoted to helping those suffering from psychiatric illnesses and whose kindness to colleagues and participants alike touched us all. We give thanks to all of the participants in this study, and hope that this work may one day contribute to helping those living with bipolar disorder. We would also like to thank Terry Hickey, R.T.R.M.R. and Hedy Sarofin, R.T.R.M.R. for their technical expertise, and acknowledge the help and support of all members of the Mood Disorders Laboratory at Yale. The authors were supported by research grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs Research Career Development (HPB), Merit Review (HPB) and Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP) Awards (LGC, HPB); the National Institute of Mental Health R01MH070902 (HPB), T32MH14276 (LGC); the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Great Neck, NY) (HPB); The Attias Family Foundation (HPB); and The Ethel F. Donaghue Women’s Investigator Program at Yale (New Haven, CT) (HPB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altshuler L, Bookheimer S, Proenza MA, Townsend J, Sabb F, Firestine A, Bartzokis G, Mintz J, Mazziotta J, Cohen MS. Increased amygdala activation during mania: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1211–1213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Gardner K, Lowe MJ. Reciprocal effects of antidepressant treatment on activity and connectivity of the mood regulating circuit: an FMRI study. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2007;19:274–282. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19.3.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Lowe MJ, Dzemidzic M. Resting state corticolimbic connectivity abnormalities in unmedicated bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. Psychiatry Research. 2009;171:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Wu J, Gao S, Bukhari L, Mathews VP, Kalnin A, Lowe MJ. Activity and connectivity of brain mood regulating circuit in depression: a functional magnetic resonance study. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce E, Simmons AN, Lovero KL, Stein MB, Paulus MP. Escitalopram effects on insula and amygdala BOLD activation during emotional processing. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:661–672. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell EC, Willson MC, Wilman AH, Dave S, Asghar SJ, Silverstone PH. Lithium and valproate attenuate dextroamphetamine-induced changes in brain activation. Human Psychopharmacology. 2005;20:87–96. doi: 10.1002/hup.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Diamond JB, Smith MA, Bandettini PA. Separating respiratory-variation-related fluctuations from neuronal-activity-related fluctuations in fMRI. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1536–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP, Donegan NH, Sanislow CA, Collins S, Lacadie C, Skudlarski P, Gueorguieva R, Fulbright RK, McGlashan TH, Gore JC, Krystal JH. Preliminary evidence for medication effects on functional abnormalities in the amygdala and anterior cingulate in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology. 2005;183:308–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP, Leung HC, Skudlarski P, Lacadie CM, Fredericks CA, Harris BC, Charney DS, Gore JC, Krystal JH, Peterson BS. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of bipolar disorder: state- and trait-related dysfunction in ventral prefrontal cortices. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003a;60:601–609. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg HP, Martin A, Kaufman J, Leung HC, Skudlarski P, Lacadie C, Fulbright RK, Gore JC, Charney DS, Krystal JH, Peterson BS. Frontostriatal abnormalities in adolescents with bipolar disorder: preliminary observations from functional MRI. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003b;160:1345–1347. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Suckling J, Ooi C, Fu CH, Williams SC, Walsh ND, Mitterschiffthaler MT, Pich EM, Bullmore E. Functional coupling of the amygdala in depressed patients treated with antidepressant medication. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1909–1918. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Anxiety and affective style: role of prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Rich BA, Roberson-Nay R, Berghorst L, Vinton D, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Neural activation during encoding of emotional faces in pediatric bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:679–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DD, Rauch SL. Brain correlates of antidepressant treatment outcome from neuroimaging studies in depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2007;30:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Ogilvie A, Rubinsztein JS, Calderon G, Dolan RJ, Sahakian BJ. Abnormal ventral frontal response during performance of an affective go/no go task in patients with mania. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foland LC, Altshuler LL, Bookheimer SY, Eisenberger N, Townsend J, Thompson PM. Evidence for deficient modulation of amygdala response by prefrontal cortex in bipolar mania. Psychiatry Research. 2008a;162:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foland LC, Altshuler LL, Sugar CA, Lee AD, Leow AD, Townsend J, Narr KL, Asuncion DM, Toga AW, Thompson PM. Increased volume of the amygdala and hippocampus in bipolar patients treated with lithium. Neuroreport. 2008b;19:221–224. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f48108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Cohen JD, Fitzgerald M, Eddy WF, Mintun MA, Noll DC. Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): use of a cluster-size threshold. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;33:636–647. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye MA, Watzl J, Banakar S, O’Neill J, Mintz J, Davanzo P, Fischer J, Chirichigno JW, Ventura J, Elman S, Tsuang J, Walot I, Thomas MA. Increased anterior cingulate/medial prefrontal cortical glutamate and creatine in bipolar depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2490–2499. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Barbas H. Pathways for emotion: interactions of prefrontal and anterior temporal pathways in the amygdala of the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 2002;115:1261–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Kiviniemi V, Tervonen O, Vainionpaa V, Alahuhta S, Reiss AL, Menon V. Persistent default-mode network connectivity during light sedation. Human Brain Mapping. 2008;29:839–847. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson M, Peterson BS, Skudlarski P, Gatenby JC, Gore JC. Detection of functional connectivity using temporal correlations in MR images. Human Brain Mapping. 2002;15:247–262. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BJ, Soriano-Mas C, Pujol J, Ortiz H, Lopez-Sola M, Hernandez-Ribas R, Deus J, Alonso P, Yucel M, Pantelis C, Menchon JM, Cardoner N. Altered corticostriatal functional connectivity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1189–1200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Buchsbaum MS, Haznedar MM, Berenguer J, Berlin HA, Chaplin W, Goodman CR, LiCalzi EM, Newmark R, Pallanti S. FDG-PET study in pathological gamblers. 1. Lithium increases orbitofrontal, dorsolateral and cingulate metabolism. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;58:37–47. doi: 10.1159/000154478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogia J, Haldane M, Cobb A, Kumari V, Frangou S. Pilot investigation of the changes in cortical activation during facial affect recognition with lamotrigine monotherapy in bipolar disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:197–201. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, George MS, Dunn RT, Speer AM, Benson BE, Willis MW, Danielson A, Frye MA, Herscovitch P, Post RM. Effects of mood and subtype on cerebral glucose metabolism in treatment-resistant bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:97–109. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00975-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T, Shiga T, Toyomaki A, Kusumi I, Matsuyama T, Inoue T, Katoh C, Koyama T, Tamaki N. Effects of lithium on brain glucose metabolism in healthy men. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;27:698–702. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815a23c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronhaus DM, Lawrence NS, Williams AM, Frangou S, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Andrew CM, Phillips ML. Stroop performance in bipolar disorder: further evidence for abnormalities in the ventral prefrontal cortex. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger S, Seminowicz D, Goldapple K, Kennedy SH, Mayberg HS. State and trait influences on mood regulation in bipolar disorder: blood flow differences with an acute mood challenge. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1274–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Sanacora G, Blumberg H, Anand A, Charney DS, Marek G, Epperson CN, Goddard A, Mason GF. Glutamate and GABA systems as targets for novel antidepressant and mood-stabilizing treatments. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7(Suppl 1):S71–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence NS, Williams AM, Surguladze S, Giampietro V, Brammer MJ, Andrew C, Frangou S, Ecker C, Phillips ML. Subcortical and ventral prefrontal cortical neural responses to facial expressions distinguish patients with bipolar disorder and major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Rich BA, Vinton DT, Nelson EE, Fromm SJ, Berghorst LH, Joshi P, Robb A, Schachar RJ, Dickstein DP, McClure EB, Pine DS. Neural circuitry engaged during unsuccessful motor inhibition in pediatric bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:52–60. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.A52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe MJ, Mock BJ, Sorenson JA. Functional connectivity in single and multislice echoplanar imaging using resting-state fluctuations. Neuroimage. 1998;7:119–132. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah L, Zarate CA, Jr., Singh J, Duan YF, Luckenbaugh DA, Manji HK, Drevets WC. Regional cerebral glucose metabolic abnormalities in bipolar II depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:765–775. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh AM, Whalley HC, McKirdy J, Hall J, Sussmann JE, Shankar P, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM. Prefrontal function and activation in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:378–384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moresco RM, Tettamanti M, Gobbo C, Del Sole A, Ravasi L, Messa C, Paulesu E, Lucignani G, Perani D, Fazio F. Acute effect of 3-(4-acetamido)-butyrril-lorazepam (DDS2700) on brain function assessed by PET at rest and during attentive tasks. Nuclear Medicine Communications. 2001;22:399–404. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northoff G, Walter M, Schulte RF, Beck J, Dydak U, Henning A, Boeker H, Grimm S, Boesiger P. GABA concentrations in the human anterior cingulate cortex predict negative BOLD responses in fMRI. Nature Neuroscience. 2007;10:1515–1517. doi: 10.1038/nn2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozerdem A, Guntekin B, Tunca Z, Basar E. Brain oscillatory responses in patients with bipolar disorder manic episode before and after valproate treatment. Brain Research. 2008;1235:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, O’Connor MM, Harral E, Sweeney JA. Affective neural circuitry during facial emotion processing in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew JD, Miller SM. A ‘sticky’ interhemispheric switch in bipolar disorder? Proceedings of the Royal Society - Biological Sciences. 1998;265:2141–2148. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Likhtik E, Pelletier JG, Pare D. Stimulation of medial prefrontal cortex decreases the responsiveness of central amygdala output neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:8800–8807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08800.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. Thieme; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Kalmar JH, Edmiston E, Chepenik LG, Bhagwagar Z, Spencer L, Pittman B, Jackowski M, Papademetris X, Constable RT, Blumberg HP. Abnormal corpus callosum integrity in bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:730–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RG, Ide K, Poulin MJ, Tracey I. Resting fluctuations in arterial carbon dioxide induce significant low frequency variations in BOLD signal. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1652–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd DA, Gruber SA, Kanayama G, Killgore WD, Baird AA, Young AD. fMRI during affect discrimination in bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2000;2:237–248. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurgelun-Todd DA, Silveri MM, Gruber SA, Rohan ML, Pimentel PJ. White matter abnormalities observed in bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:504–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]