Abstract

Despite research documenting variability in the sexual identity development of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youths, it remains unclear whether different developmental patterns have implications for the psychological adjustment of LGB youths. The current report longitudinally examines whether different patterns of LGB identity formation and integration are associated with indicators of psychological adjustment among an ethnically diverse sample of 156 LGB youths (ages 14 – 21) in New York City. Although differences in the timing of identity formation were not associated with psychological adjustment, greater identity integration was related to less depressive and anxious symptoms, fewer conduct problems, and higher self-esteem both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. Individual changes in identity integration over time were associated with all four aspects of psychological adjustment, even after controlling for rival hypotheses concerning family and friend support, gay-related stress, negative social relationships, and other covariates. These findings suggest that difficulties in developing an integrated LGB identity may have negative implications for the psychological adjustment of LGB youths and that efforts to reduce distress among LGB youths should address the youths’ identity integration.

Keywords: sexual identity development, coming-out process, mental health, depression, anxiety, social support, gay-related stress, internalized homophobia, disclosure, sexual orientation, longitudinal

The formation and integration of a lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) identity can be a complex and often difficult process. Although youths from other minority backgrounds are raised in families and communities that are supportive of their minority identity, LGB youths often struggle to accept their sexual identity in the context of ignorance, prejudice, and often violence against same-sex sexuality (Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Huebner, Rebchook, & Kegeles, 2004). However, not all LGB youths experience such adverse reactions nor do all LGB youths experience difficulty in accepting and integrating their developing sexual identity (Eccles, Sayegh, Fortenberry, & Zimet, 2004; Savin-Williams, 2005). For those who do experience difficulties with their sexual identity development, poorer psychological adjustment may result. The current report examines whether differences in the formation and integration of an LGB identity are associated with the subsequent psychological adjustment of LGB youths.

We base our conceptualization of sexual identity development on the work of Erik Erikson. The process of identity development consists of identity formation, in which the internal reality of the individual begins to assert and demand its expression as earlier identifications are discarded or reconfigured (Erikson, 1956/1980; 1968). Identity development also consists of identity integration, in which a commitment to and integration of the evolving identity with the totality of the self are expected, although not guaranteed (e.g., Kroger, 2007; Marcia, 1966). Identity integration involves an acceptance of the unfolding identity, its continuity over time and settings, and a desire to be known by others as such; none of which is surprising given identity integration concerns an inner commitment and solidarity with whom one is (Erikson, 1946/1980, 1968). The antithesis of identity integration is diffusion or confusion; a sense of self as other or inauthentic either because an invalid identity has been assumed or foisted upon one, or because one is searching for a meaningful identity (Erikson, 1946/1980, 1956/1980, 1968). Although most theories of LGB identity development do not explicitly reference Erikson’s more general theory of identity development, the general notions of identity formation and integration are implicit in the models (Cass, 1979; Chapman & Brannock, 1987; Fassinger & Miller, 1996; Troiden, 1989).

In keeping with Erikson, sexual identity development is conceived as having two related developmental processes (Morris, 1997; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Braun, 2006). The first, identify formation, is the initiation of a process of self-discovery and exploration of one’s LGB identity, including becoming aware of one’s sexual orientation, questioning whether one may be LGB, and having sex with members of the same sex (e.g., Chapman & Brannock, 1987; Fassinger & Miller, 1996; Troiden, 1989). The second, identity integration, is a continuation of sexual identity development as individuals integrate and incorporate the identity into their sense of self and thereby increase their commitment to the new LGB identity (Morris, 1997; Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001; Rosario et al., 2006). Specifically, identity integration is composed of engaging in LGB-related social activities, working through negative attitudes toward homosexuality, feeling more comfortable with other individuals knowing about their LGB identity, and disclosing that identity to others (Morris, 1997; Rosario et al., 2001; 2006).

Unlike many past theoretical models of LGB identity development (e.g., Cass, 1979; Troiden, 1989), we do not conceptualize identity formation and integration as a stage model. Not only may identity formation and integration co-occur, but LGB youths may experience a diversity of developmental patterns (e.g., Dube, 2000; Floyd & Stein, 2002; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). For example, some youths may pass through all milestones at an early age, others at a later age, and others may stagnate in their identity formation (Floyd & Stein, 2002). Likewise, sexual exploration may occur before or after adopting an LGB identity (Dubé, 2000). However, with few exceptions (Diamond, 2005; Rosario et al., 2006), these patterns have been retrospectively reported; prospective longitudinal studies are needed to document developmental patterns.

Despite the interest in documenting the variability in patterns of LGB sexual identity development, of critical concern are the implications of different developmental patterns for adjustment, given the high rates of depression, anxiety, suicidality and other behavioral problems documented among representative samples of LGB youths (e.g., Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Fergusson, Horwood, & Beautrais, 1999; Udry & Chantala, 2002). Of concern are youths who initiate their sexual identity development at an early age because they may lack the coping skills necessary to negotiate the stresses of this development. Furthermore, those who have only recently initiated LGB identity development (regardless of age) may be at greater risk for poor psychological adjustment because it takes time to work through and accept the new identity. Also of potential concern are those LGB youths who are delayed in their development or those who remain consistently low in their identity integration.

Several studies of LGB youths and adults have examined the relations between sexual identity development and psychological adjustment. With respect to age of developmental milestones of identity formation, studies have largely found no evidence, with neither earlier awareness of sexual orientation nor earlier identification as LGB associated with substance use (Parks & Hughes, 2007), suicidal ideation (Igartua, Gill, & Montoro, 2003), or depression and anxiety (D’Augelli, 2002). Further, in the only study that examined how different patterns of LGB identity formation milestones were related to psychological adjustment, the findings did not support the hypothesis that early developing youths would be at greater risk for low self-esteem or more psychological distress (Floyd & Stein, 2002). This research also failed to identify any differences between LGB youths who progressed through identity development and those who stagnated in their development (Floyd & Stein, 2002). Despite the lack of research identifying an association between identity formation and adjustment, the broader literature on identity development of other groups (e.g., adolescent identity, ethnic identity, general sexual identity) has demonstrated that a stagnated identity development is associated with poorer adjustment (Adams et al., 2001; Archer & Grey, 2009; Kiang, Yip, & Fuligni, 2008; Marcia, 1966; Muise, Preyde, Maitland, & Milhausen, in press). Given the limited amount of research examining identity formation and adjustment among LGB youths, further research is needed.

In contrast to identity formation, aspects of identity integration have been linked to psychological adjustment among both LGB youths and adults. More positive attitudes toward homosexuality (e.g., Balsam & Mohr, 2007; Morris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001; Rosario et al., 2001; Wright & Perry, 2006), greater openness and disclosure of one’s sexuality (D’Augelli, 2002; Jordan & Deluty, 1998; Morris et al., 2001), and greater involvement in the LGB community (Morris et al., 2001) have each been found to be associated with greater psychological adjustment. Relatedly, LGB individuals who are further along in integrating their sexual identity have been found to have higher self-esteem (Halpin & Allen, 2004; Swann & Spivey, 2004). Nevertheless, these past studies either have been based on retrospective recall or have been cross-sectional in design. As such, studies have not examined whether changes in sexual identity development are associated with subsequent psychological adjustment.

Any role that different patterns of sexual identity development may have for the psychological adjustment of LGB youths must exist independent of other important social-context factors that have been associated with their adjustment. Experiences of gay-related stressful events (e.g., rejection, ridicule, victimization) have been associated with poor psychological adjustment among LGB individuals (e.g., Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Huebner et al., 2004; Mills et al., 2004; Ueno, 2005). Supportive friends and family are particularly important for the psychological adjustment of LGB youths (e.g., Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2005; Ueno, 2005), whereas unsupportive family and friends may be detrimental to their mental health (Lewis, Derlega, Clarke, & Kuang, 2006; Rosario et al., 2005; Ueno, 2005). In addition, the existence of a supportive or stressful social context may promote or inhibit sexual identity development (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2008; Mohr & Fassinger, 2003). Finally, the developmental patterns may differ by sex and sexual identity as lesbian/gay v. bisexual (e.g., Grov, Bimbi, Nanin, & Parsons, 2006; Maguen, Floyd, Bakeman, & Armistead, 2002).

Building on our earlier work with this sample, in which different patterns of sexual identity development were identified (Rosario et al., 2008), the current report investigates the heretofore unexamined roles of identity formation and changes in identity integration on the subsequent psychological adaptation of LGB youths. Specifically, we hypothesized that LGB youths who begin identify formation more recently than other youths may be at risk for poorer psychological adjustment. Further, we hypothesize that greater identity integration and increases in identity integration over time will be associated with higher subsequent psychological adjustment. We also examine whether and how different patterns of sexual identity development are associated with psychological adjustment after accounting for other important social-context factors known to be critical for the psychological adjustment of LGB youths (i.e., family and friend support, negative social relationships, and experiences of gay-related stress). Similarly, we control for socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., sex) that covary with sexual identity development or adjustment.

METHOD

Participants

One-hundred and sixty-four youths, ages 14 to 21 years, were recruited from three LGB-focused community-based organizations (CBOs, 85%) and two LGB college student organizations in New York City. Eight youths were excluded because they did not meet eligibility criteria,resulting in 156 youths (49% female), mean age of 18.3 years (SD = 1.65). The 156 youths identified as lesbian or gay (66%), bisexual (31%), or other (3%). They were Latino (37%), Black (35%), White (22%), or Asian and other ethnic backgrounds (7%). Of the youths, 34% reported having a parent who received welfare, food stamps, or Medicaid.

Procedure

Youths provided voluntary and signed informed consent. The Commissioner of Mental Health for New York State waived parental consent for youths under age 18. Instead, an adult at each CBO served in loco parentis to safeguard the rights of every minor in the study. The university’s Institutional Review Board and recruitment sites approved the study.

A 2- to 3-hour structured interview was conducted at recruitment with follow-up interviews occurring 6 and 12 months later. Interviews were conducted in a private room at the recruitment sites at baseline and in a private location convenient for the youths at subsequent assessments. Interviews were conducted by college-educated individuals of the same sex as the youth and who were comfortable with LGB individuals. Because the current report focuses on changes that occur between recruitment (Time 1) and the 12-month assessment (omitting the 6-month assessment to maximize change over time) we have designated the 12-month assessment as Time 2. Youths were interviewed between October 1993 and June 1994, with follow-up interviews conducted through August 1995. The retention rate was 90% (n = 140) for the 12-month assessment. Youths received $30 at each interview.

Measures of Sexual Identity Formation

Milestones of sexual identity formation were assessed by the Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment - Youth (SERBAS-Y) for LGB youths (Meyer-Bahlburg, Ehrhardt, Exner, & Gruen, 1994), which has demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability over two weeks (Schrimshaw, Rosario, Meyer-Bahlburg, & Scharf-Matlick, 2006). Youths were asked the ages when they were first erotically attracted to, fantasized about, and were aroused by erotica focusing on the same sex. The mean age of these three milestones was computed to obtain the age of first awareness of same-sex sexual orientation (Cronbach’s α = .88). In addition, youths were asked about the age when they first thought they “might be” lesbian/gay or bisexual and when they first thought they “really were” lesbian/gay or bisexual. Finally, they were asked about the age when they first experienced any of several sexual activities with the same sex, with the earliest age in which they engaged in any of these sexual activities used as the age of their first same-sex sexual encounter. As we noted earlier, sexual identity development necessarily takes time to work through and integrate. Consequently, we have argued that more important than age when milestones occur is the length of time between first experiencing these milestones and the present (Rosario et al., 2006). Thus, for all four developmental milestones, we computed the number of years since the youth first experienced the various milestones by subtracting the age at each milestone from the youth’s age at Time 1.

Measures of Sexual Identity Integration

Involvement in LGB-Related Activities

A 28-item checklist assessed lifetime involvement in gay-related social and recreational activities at all assessments (Rosario et al., 2001). At follow-up assessments, youths were asked about their activity involvement during the past 6 months (i.e., since their last assessment). Factor analysis of the Time 1 data generated 11 items that loaded on one factor (e.g., going to a gay bookstore, coffee house). A count of the 11 items endorsed by the youths was computed (Cronbach’s αTime 1 = .77 and αTime 2 = 64).

Positive Attitudes Toward Homosexuality/Bisexuality

A modified version of the Nungesser Homosexual Attitudes Inventory (NHAI; Nungesser, 1983) was administered at all assessments, in which the language was simplified for youths and the item content was made appropriate for female youths. The measure utilized a 4-point response scale ranging from “disagree strongly” (1) through “agree strongly” (4). A factor analysis of the Time 1 data resulted in two factors. The first factor, composed of 11 items, assessed attitudes toward homosexuality [e.g., “My (homosexuality/ bisexuality) does not make me unhappy”]. The mean of these items was computed at each assessment, with high scores indicating more positive attitudes toward homosexuality (Cronbach’s αTime 1 = .85 and αTime 2 = 83). Because these data were negatively skewed at all assessments, they were transformed using the exponential e to stretch the positive end of the distribution.

Comfort with Others Knowing about Your Homosexuality/Bisexuality

As noted above, a factor analysis of the Time 1 data from the NHAI (Nungesser, 1983) identified two factors. The second factor, composed of 12 items, assessed comfort with other individuals knowing about the youth’s sexuality [e.g., “If my straight friends knew of my (homosexuality/bisexuality), I would feel uncomfortable”]. The mean of these items was computed at each time period, with a high score indicating more comfort with homosexuality (Cronbach’s αTime 1 = .90 and αTime 2 = .91).

Disclosure of Homosexuality/Bisexuality to Others

Youths were asked at Time 1 to enumerate “all the people in your life who are important or were important to you and whom you told that you are (lesbian/gay/bisexual)” (Rosario et al., 2001). Subsequently, youths were asked about the number of new individuals to whom the youth had disclosed during the past six months (i.e., since their last assessment). Because disclosure cannot be undone, the indicator of disclosure is cumulative over time. Therefore, the disclosure data at Time 1 were summed with new disclosures at the 6- and 12-months assessments as our self-disclosure indicator at the last assessment. A logarithmic transformation was imposed at Time 2 because these disclosure data were positively skewed.

Measures of Psychological Adjustment

Psychological Distress

Depressive and anxious symptoms during the past week were assessed by means of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, 1993) at all assessments, using its “not at all” (0) to “extremely” (4) distressing response scale. The mean of each subscale was computed, with high scores indicating elevated distress. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) ranged from .80 to .70 for anxious symptoms and from .82 to .74 for depressive symptoms at Time 1 and Time 2, respectively.

Conduct Problems

As the BSI assesses only internalized distress, conduct problems were included as indicators of externalized psychological distress. A 13-item index, based on the conduct problems identified in DSM-III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987), was created to assess the number of conduct problems experienced by the youths, such as skipping school, vandalism, stealing, fighting, and running away. A count of the problems endorsed by the youth was computed.

Self-Esteem

Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item scale was administered at all assessments, with its four-point Likert response scale ranging from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (4), to assess positive self-evaluation (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”). The mean was computed, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem (Cronbach’s αTime 1 = .86 and αTime 2 = .83).

Measures of Social Context and Other Potential Covariates

Social Support from Family and Friends

Procidano and Heller’s (1983) measures of perceived social support from family and from friends were adapted, deleting items that might be confounded with psychological health. The two resulting 12-item measures were administered at Time 1 and using a yes (1) or no (0) response format (e.g., “I rely on my [family/friends] for emotional support”). A count of the items endorsed was the index of social support from family (Cronbach’s α = .90) and friends (Cronbach’s α = .80).

Negative Social Relationships

The 12-item Social Obstruction Scale (Gurley, 1990) was administered at Time 1 to assess the presence of negative social relationships with others, including being treated poorly, being ignored, and being manipulated by others (e.g., “Somebody treats me as if I were nobody”). Items use a response scale ranging from “definitely false” (1) to “definitely true” (4). The mean was computed, with higher scores indicating greater levels of negative social relationships (Cronbach’s α = .85).

Gay-Related Stressful Life Events

A 12-item checklist of stressful events related to homosexuality was administered at Time 1 (e.g., “Losing a close friend because of your [homosexuality/bisexuality]”: Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002). The youths indicated whether they had experienced any of the events within the past 3 months. The number of events experienced was computed. Because the responses were skewed, we computed a response scale of zero (0), or one or more (1) stressful events.

Social Desirability

The tendency to provide socially desirable responses was assessed at Time 1 by means of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1964). We used its original true-false response format, but deleted 2 of 33 items we considered inappropriate for youths. A factor analysis generated 12 items that loaded on a single factor (e.g., “I have never deliberately said something that hurt someone’s feelings”). The number of these items endorsed composed the indicator of social desirability (Cronbach’s α = .74).

Data Analysis

Cluster analysis was used to identify naturally occurring subgroups of LGB youths on sexual identity formation and integration. Cluster analysis is an inductive procedure to determine whether groups exist based on inherent patterns of associations among the variables of interest (e.g., Everitt, Landau, & Leese, 2001; Henry, Tolan, & Gorman-Smith, 2005; Rapkin & Luke, 1993). Rather than imposing a priori categories on the data, cluster analysis allows for the identification of potentially heretofore unidentified groups based on the data themselves. Cluster analysis is also particularly useful here, given the potentially non-linear nature of identity development.

The cluster analysis used a two-step procedure to identify and validate the identified groups. Hierarchical clustering, a procedure that utilizes Euclidian distances among cases on the standardized variables of interest, was used to determine the number of groups or clusters by means of dendograms revealing how the individuals group together. In a second cluster analysis, we aimed to validate and define the profiles of the original cluster solution by the K-means cluster analytic procedure. This procedure was followed for identity formation and identity integration clusters at Time 1. A similar K-means procedure was used for the 12-month data (Time 2) to identify if identity cluster membership was consistent or changed over time. To ensure the clusters were comparable, we used the cluster centers (i.e., means) identified at Time 1 to assign youths to equivalent clusters based on the Time 2 data.

To examine differences among our identity formation and identity integration clusters by psychological adjustment and potential covariates, we used ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. Next, individual-level change in identity integration group membership was examined. We tracked changes in identity integration from Time 1 to Time 2 in the clusters by individual youths, determining whether they remained in the same cluster or changed clusters over the year. Finally, the correlates of these individual-level changes were examined at both the bivariate (using ANOVA and chi-square) and multivariate (using multiple linear regression) levels. For all analyses, effect sizes are presented in the form of the proportion of explained variance: η2 for ANOVA, its equivalent τ for chi-square analysis (Goodman & Kruskal, 1979), and the standardized regression coefficient (β) for multiple regression.

RESULTS

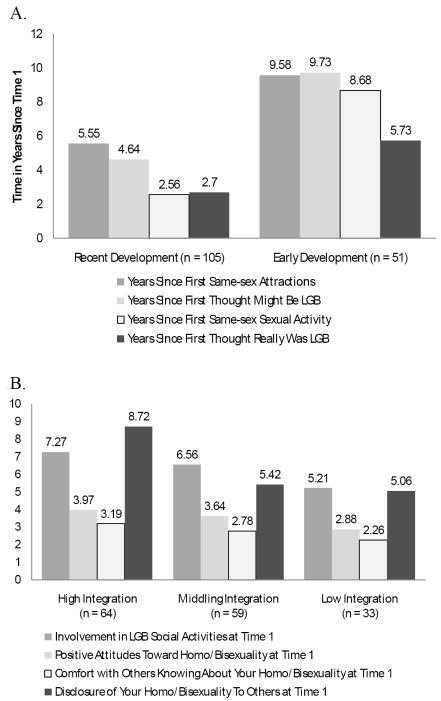

To examine potential patterns of LGB identity formation and identity integration, indicators of sexual identity development were cluster analyzed, the results of which are presented elsewhere (Rosario et al, 2008). In summary, three sets of cluster analysis were conducted. First, an analysis of length of time since achieving each of four identity formation milestones (i.e., years since first being attracted to the same sex, years since first thinking one might be LGB, years since first thinking one really was LGB, and years since first same-sex sexual encounter) generated two clusters: one composed of youths whose identity developed earlier (33%) and a second of youths whose identity formation was more recent (67%). Consistent with the cluster analysis, youths in the two clusters significantly differed on each of the four milestones examined (see Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Sexual identity formation cluster groups at Time 1 (1A) and sexual identity integration cluster groups at Time 1 (1B) and Time 2 (1C).

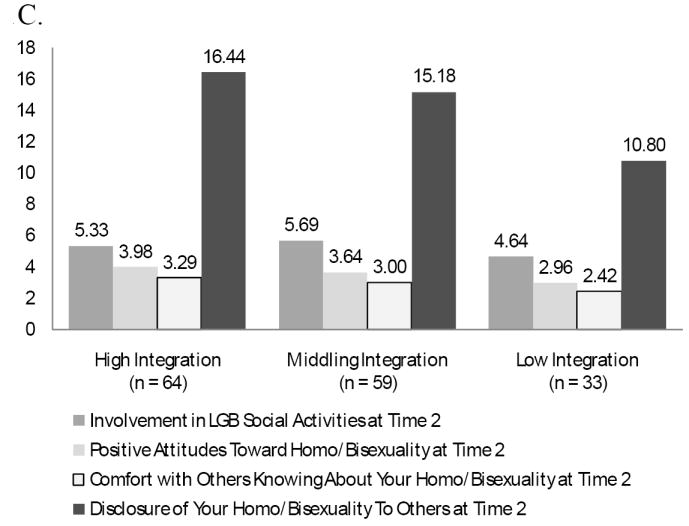

Second, four aspects of identity integration at Time 1, (i.e., involvement in gay-related social activities, positive attitudes toward homosexuality/bisexuality, comfort with other individuals learning about one’s homosexuality/bisexuality, and disclosing that sexuality to others) were cluster analyzed. Three clusters emerged: high, middling, and low integration. A comparison of the three identity integration groups indicated that the groups differed significantly on all four indicators of identity integration (see Figure 1B).

Third, the cluster analysis of identity integration at Time 2 (a year later) was conducted relative to the centroids of the Time-1 clusters. Thus, this analysis took into account potential change in clusters from Time 1 to Time 2. Three clusters were found at Time 2, consisting of youths low, middling, or high on identity integration. The three groups differed significantly on two of four indicators of identity integration, changing over time on positive attitudes toward and comfort with homosexuality/bisexuality (see Figure 1C).

Identity Groups and Psychological Adjustment

Differences in psychological distress and self-esteem by the sexual identity developmental groups were examined (see Table 1). A comparison of youths whose LGB identity formation had occurred earlier v. more recently found that the two groups did not differ significantly on any indicator of psychological adjustment at Time 1 or Time 2.

Table 1.

Mean Differences Between Identity Formation Groups and Identity Integration Groups in Psychological Adjustment.

| Identity Formation Groups: Time 1 |

Test Statistic | Effect Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent Development (n = 105) | Early Development (n = 51) | ||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | F | η2 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | |||||

| Time 1 | 1.04 (0.87) | 1.15 (0.86) | 0.59 | .00 | |

| Time 2 | 0.72 (0.67) | 0.81 (0.88) | 0.46 | .00 | |

| Anxiety Symptoms | |||||

| Time 1 | 1.17 (0.85) | 1.32 (1.04) | 0.85 | .01 | |

| Time 2 | 0.76 (0.76) | 0.72 (0.71) | 0.10 | .00 | |

| Conduct Problems | |||||

| Time 1 | 1.92 (1.57) | 1.82 (1.61) | 0.14 | .00 | |

| Time 2 | 1.34 (1.35) | 1.33 (1.25) | 0.00 | .00 | |

| Self-Esteem | |||||

| Time 1 | 3.36 (0.48) | 3.28 (0.55) | 0.96 | .01 | |

| Time 2 | 3.49 (0.43) | 3.48 (0.47) | 0.02 | .00 | |

| Identity Integration Groups: Time 1 |

Test Statistic | Effect Size | |||

| High (n = 64) | Middling (n = 59) | Low (n = 33) | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | η2 | |

| Depressive Symptoms | |||||

| Time 1 | 0.74 (0.77) a | 1.23 (0.81)b | 1.44 (0.92)b | 9.75*** | .11 |

| Time 2 | 0.49 (0.59)a | 1.00 (0.79)b | 0.79 (0.81) | 6.75** | .09 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | |||||

| Time 1 | 1.08 (0.90) | 1.25 (0.88) | 1.44 (0.99) | 1.81 | .02 |

| Time 2 | 0.53 (0.65)a | 0.85 (0.73)b | 0.98 (0.84)b | 4.62* | .06 |

| Conduct Problems | |||||

| Time 1 | 1.81 (1.67) | 2.02 (1.58) | 1.82 (1.40) | 0.30 | .00 |

| Time 2 | 1.11 (0.94)a | 1.34 (1.41) | 1.77 (1.63)b | 2.55† | .04 |

| Self-Esteem | |||||

| Time 1 | 3.45 (0.44)a | 3.32 (0.53) | 3.14 (0.51)b | 4.45* | .06 |

| Time 2 | 3.64 (0.35)a | 3.37 (0.47)b | 3.38 (0.46)b | 6.52** | .09 |

| Identity Integration Groups: Time 2 |

Test Statistic | Effect Size | |||

| High (n = 57) | Middling (n = 55) | Low (n = 28) | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | η2 | |

| Depressive Symptoms | |||||

| Time 2 | 0.63 (0.66)a | 0.70 (0.70)a | 1.09 (0.92)b | 3.93* | .05 |

| Anxiety Symptoms | |||||

| Time 2 | 0.54 (0.58)a | 0.75 (0.75)b | 1.18 (0.85)b | 7.68*** | .10 |

| Conduct Problems | |||||

| Time 2 | 1.11 (1.14)a | 1.22 (1.03)a | 2.04 (1.84)b | 5.41** | .07 |

| Self-Esteem | |||||

| Time 2 | 3.63 (0.34)a | 3.46 (0.44)b | 3.22 (0.52)c | 8.98*** | .12 |

Note. Means with differing superscripts differ at p < .05.

p < .08,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Significant differences were found in psychological adjustment by identity integration groups (see Table 1). The three integration groups at Time 1 differed on their concurrent (Time 1) and subsequent (Time 2) distress and self-esteem. Post-hoc comparisons found that highly integrated youths reported significantly less anxious and depressive symptoms, fewer conduct problems, and higher self-esteem, especially at Time 2, than did youths with low integration. Youths with middling integration sometimes differed significantly from youths with high integration, reporting more distress or lower self-esteem than highly integrated peers.

Identity integration groups at Time 2 also differed on psychological distress and self-esteem at Time 2. By Time 2, psychological distress, with the exception of anxiety, did not differ significantly between the high and middling integrated youths, but both groups of youths differed from youths low in integration. All groups differed on self-esteem, with the highly integrated group reporting the highest self-esteem and the low integrated group reporting the lowest self-esteem.

Individual Change in Identity Integration and Psychological Adjustment

Close examination of the integration data at the individual level indicated that youths followed a number of different patterns of change over time in identity integration, including a large number who remained consistent over time (see Rosario et al., 2008, for details). Five patterns of change contained enough youths for statistical comparisons on psychological adjustment.

A comparison of these five integration-change groups on subsequent psychological distress and self-esteem at Time 2 was conducted (Table 2). All F tests were significant. Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated that youths who were consistently high in integration generally reported lower psychological distress than other youths, with the exception of youths who decreased from high to middling, who often did not differ from consistently high youths. Youths who were consistently high, those who increased from low/middling to high, or those who decreased from high to middling reported higher self-esteem at Time 2 than youths who were consistently middling or low in integration over time.

Table 2.

Mean Comparisons between Consistency and Change in Individual-Level Identity Integration and Subsequent Psychological Adjustment Outcomes and Social Context Factors.

| Consistency or Change in Identity Integration Groups from Time 1 to Time 2 |

Test Statistic | Effect Size | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistently High (n = 39) | Increased from Low/Middlin g to High (n = 18) | Decreased from High to Middling (n = 16) | Consistently Middling (n = 28) | Consistently Low (n = 18) | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | η2 | |

| Adjustment Outcomes At Time 2: | |||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.48 (0.56)a | 0.94 (0.77)b | 0.46 (0.66)a | 0.94 (0.69)b | 1.04 (0.83)b | 3.87** | .12 |

| Anxious Symptoms | 0.46 (0.51)a | 0.71 (0.68)ab | 0.68 (0.88)ab | 0.88 (0.76)b | 1.33 (0.85)c | 5.01*** | .15 |

| Conduct Problems | 0.85 (0.71)a | 1.67 (1.65)b | 1.63 (0.96)b | 0.89 (0.88)a | 2.06 (1.80)b | 4.97*** | .15 |

| Self Esteem | 3.63 (0.36)a | 3.62 (0.30)a | 3.66 (0.33)a | 3.31 (0.46)b | 3.23 (0.46)b | 5.92*** | .17 |

| Social Context Variables at Time 1: | |||||||

| Family Support | 6.97 (4.17) a | 6.06 (3.72) | 8.56 (4.13)a | 6.43 (4.00) | 4.56 (3.79)b | 2.32† | .08 |

| Friend Support | 10.39 (2.46)a | 9.39 (2.59) | 10.81 (1.91)a | 10.71 (1.96)a | 8.67 (2.45)b | 3.21* | .10 |

| Negative Social Relationships | 2.00 (0.71)a | 2.26 (0.72) | 1.91 (0.64)a | 2.21 (0.66)a | 2.64 (0.75)b | 3.25* | .10 |

| Gay-Related Stress | 28%a | 44% | 31%a | 32%a | 67%b | χ2 = 8.92† | τ = .08 |

Note. Means with differing superscripts differ at p < .05. For comparison purposes, adolescent normative means for depressive symptoms and anxious symptoms are 0.82 and 0.78, respectively (Derogatis, 1993).

p < .08,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Social-Context Factors

Social relationships and gay-related stress at Time 1 were related significantly to psychological adjustment at Time 2. Youths with more family and friend support experienced less depressive symptoms (r = -.26 and -.20, respectively). Friend support was related to fewer conduct problems (r = -.19), and family support was related to higher self-esteem (r = .26). Conversely, youths with more negative social relationships reported more anxious and depressive symptoms, more conduct problems, and lower self-esteem (r = .28, .30, .24, -.36, respectively). Youths who experienced gay-related stress reported more anxious symptoms (r = .17).

In addition, the social-context factors at Time 1 were related to individual-level change in identity integration (Table 2). Follow-up, significant pairwise comparisons indicated, for example, that youths with more family and friend support were more likely to be consistently high in integration or to decrease from high to middling integration than were youths who were consistently low in integration.

Other Potential Covariates

We examined potential rival explanations associated with demographic and related factors that might account for relations between individual change in identity integration and adjustment at Time 2. Sex was associated with the identity integration change groups, χ2 (4, N = 119) = 12.46, p < .05, with pairwise comparisons indicating that youths who were consistently low over time were significantly more likely to be male as compared with youths who were consistently high or middling, who increased from low/middling to high, or who decreased from high to middling; these youths were more likely to be female or to represent both sexes fairly equally. Sex was unrelated to any indicator of psychological adjustment.

Identification as lesbian/gay as compared with bisexual was related to change in identity integration over time, χ2 (4, N = 116) = 15.76, p < .005, but unrelated to psychological adjustment. Post-hoc comparisons showed that youths who identified as lesbian or gay were less likely than those who identified as bisexual to report consistently low identity integration.

The tendency to provide socially desirable responses at Time 1 was associated with change in identity integration over time, F (4, 114) = 3.12, p < .05. Follow-up pairwise comparisons found that youths who were consistently high in integration over time significantly reported more social desirability than youths who were consistently low or middling in integration. Social desirability at Time 1 also was related significantly to the adjustment outcomes at Time 2, such that youths who provided more socially desirable responses reported less distress associated with anxious (r = -.20) and depressive (r = -.22) symptoms, fewer conduct problems (r = -.15, p < .10), and higher self-esteem (r = .28) than youths who reported fewer socially desirable responses.

Age, SES, and ethnicity/race were not related significantly either to change in identity integration or any of the adjustment outcomes. Therefore, no statistical controls were imposed for these factors in subsequent analyses.

Multivariate Analyses Predicting Psychological Adjustment

To examine whether individual-level changes in identity integration over time were associated with youths’ psychological adjustment at Time 2, over and above that already accounted for by social-context factors and other potential covariates, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted. First, we controlled for sex, sexual identity, social desirability, and the social-context factors. We then entered the identity-integration-change groups, specifying the youths who were consistently low over time as the reference group in dummy coded variables.

Table 3 contains the multivariate findings. As anticipated, the social-context factors were significantly associated with psychological adjustment, with more negative social relationships at Time 1 associated with more psychological distress and poorer self-esteem at Time 2. Social support, sex, and sexual identity (gay/lesbian vs. bisexual) were unrelated to psychological adjustment.

Table 3.

Multivariate Associations of Changes in Individual-Level Identity Integration and Subsequent Psychological Adjustment.

| Time 1 Variables | Adjustment Outcomes at Time 2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | Anxious Symptoms | Conduct Problems | Self-Esteem | |||||

| β | β | β | β | β | B | β | β | |

| Step 1: Demographics and Social Context | ||||||||

| Female vs. Male | .00 | .07 | -.08 | .06 | -.07 | -.02 | .01 | -.07 |

| Social Desirability | -.15 | -.09 | -.09 | -.05 | -.10 | -.08 | .21* | .17† |

| Gay/Lesbian vs. Bisexual | .08 | .11 | -.01 | .11 | -.01 | .03 | .05 | -.04 |

| Family Support | -.13 | -.11 | .01 | .04 | -.01 | -.04 | .14 | .11 |

| Friend Support | -.15 | -.12 | -.12 | -.06 | -.12 | -.06 | .03 | .02 |

| Negative Social Relationships | .24* | .20* | .22* | .14 | .19† | -.17† | -.29** | -.24* |

| Gay-Related Stress | -.18† | -.20* | .17† | .09 | -.05 | -.11 | .11 | .14 |

| Step 2: Change in Identity Integration | ||||||||

| Consistently Higha | -.27† | -.58*** | -.31† | .36* | ||||

| Increased from Low/Middling to Higha | -.01 | -.35** | -.02 | .31** | ||||

| Decreased from High to Middlinga | -.18 | -.40** | .02 | .28* | ||||

| Consistently Middlinga | .01 | -.33* | -.31* | .08 | ||||

| R2 | .17** | .24** | .15* | .26*** | .08 | .18* | .21*** | .30*** |

| ΔR2 | .06† | .11** | .11** | .09** | ||||

Note: For each psychological adjustment outcome, two regression models were examined, one with and one without the inclusion of change in identity integration.

Consistently low integration was the contrast category.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

More importantly, changes in identity integration over time were consistently associated with psychological adjustment even after controlling for the social-context factors and other covariates. Specifically, LGB youths who were consistently high in identity integration over time reported less anxious symptoms and higher self-esteem than youths who were consistently low in integration. There was also a marginally significant trend for consistently high-integration youths to report less depressive symptoms and fewer conduct problems than consistently low integrated youths. This pattern was not restricted to just the consistently high youths. Youths who increased from low/middling to high integration, youths who decreased from high to middling integration, and youths who were consistently middling in their integration were also found to report significantly less anxious symptoms and higher self-esteem than consistently low youths. In addition, consistently middling youths reported fewer conduct problems than consistently low youths.

Discussion

There has been increasing recognition that the sexual identity development of LGB youths may follow multiple paths. Indeed, in our previous work (Rosario et al., 2008) we found that LGB youths followed two different patterns of identity formation and three different patterns of identity integration. Building on this earlier work, and on earlier cross-sectional research linking aspects of sexual identity development to psychological adjustment (Rosario et al., 2001), this report examined the associations of LGB identity development with psychological distress (i.e., symptoms of anxiety, depression, and conduct problems) and self-esteem. Given that LGB youths followed different developmental patterns, we hypothesized that psychological adjustment would differ by the developmental patterns.

Identity Development and Psychological Adjustment

Consistent with some past research (e.g., D’Augelli, 2002; Floyd & Stein, 2002), we found that patterns of identity formation (early vs. recent development) were not significantly related to psychological distress and self-esteem. This may be because too much time had elapsed since experiencing even “recent” identity formation and subsequent psychological adjustment, resulting in a dilution of the relations between formation and adaptation. If correct, research on youths who are just becoming aware of their LGB sexuality is needed to examine the relation between identity formation and adjustment. Such research should be conducted longitudinally in order to understand how and why the hypothesized relations attenuate over time.

In contrast to the formation findings, different identity integration groups were found to significantly differ on all four indicators of psychological adjustment, both cross-sectionally and over time. Thus, identity integration has short-term and longer-term implications for the psychological adjustment of LGB youths.

The relation of identity integration to adjustment also was evident when individual changes in identity integration over time were examined. These findings indicated that youths who were consistently high in integration or had previously been high in integration experienced greater psychological adjustment than other youths. The finding suggests that the latter youths were protected by the immunity afforded by being highly integrated at one point. By comparison, youths who were consistently low in integration reported the highest levels of distress and the lowest self-esteem. The totality of these findings underscores both the benefits of achieving and maintaining identity integration and the costs associated with low identity integration. Such findings are supported by similar findings on heterosexual youths with respect to other identities, including ethnic, family, and religious identities (e.g., Adams et al., 2001; Kiang et al., 2008). Our findings extend the previous research on aspects of LGB identity integration by finding that identity integration is longitudinally associated with adjustment (rather than just cross-sectionally correlated) and that changes in individual-level identity integration are associated with corresponding changes in adjustment over time.

Our findings on the benefits of identity integration for psychological adjustment were found despite the fact that the youths were recruited from gay-focused programs. One might expect such youths to be further along in identity development than youths recruited elsewhere and, thus, to generate attenuated relations involving identity development. Nevertheless, even among youths recruited from gay-focused settings, variability existed both at the time of recruitment into the study and over the course of a year. Among a more representative sample of youths, the magnitude of the relations reported here might be much stronger.

Covariates of Adjustment and Changes in Individual-Level Identity Integration

Despite the strong associations found between identity integration and psychological adjustment, we also recognize that the social contexts in which LGB youths live can have important implications for their psychological adjustment. Indeed, we found that supportive relationships were related to better psychological adjustment and that negative social relationships were related to poorer adjustment. In addition, supportive and negative social relationships were related to change in individual-level identity integration. Therefore, it was possible that the association between sexual identity integration and adjustment might be due to social relationships.

Although not one of our original hypotheses, some mediational evidence was found for depressive symptoms (i.e., change in identity integration was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms after controlling for social context). Nevertheless, the correlates did not mediate the relations between identity integration and the outcomes of anxiety, conduct problems, and self-esteem. As valuable as supportive relationships are for the individual’s mental and physical well-being (e.g., Uchino, 2004; Wills & Fegan, 2001), our findings suggest that identity integration captures much more than can be explained solely by social relationships. LGB identity integration, as stated at the beginning of this report, involves both acceptance and commitment to one’s sexuality. Social relationships may affect the individual’s identity integration (e.g., retarding it for some time), as we suggested earlier, but they do not exclusively determine it (Rosario et al., 2008).

Given the sense of identity integration articulated above, it was hardly surprising that youths who were consistently high on integration reported higher psychological adjustment than youths who were consistently low in integration, after controlling for social relationships, gay-related stress, and other covariates. Comparable adjustment differences also were found between other youths (e.g., consistently middling, increasing, and decreasing youths) and the consistently low youths, suggesting that youths who were working on their integration were doing much better than youths who were consistently low in integration. Thus, and as suggested earlier, there are psychological taxes to be paid for stagnation at low levels of identity integration. As such, the findings suggest that LGB youths who are consistently low in integration should be identified and targeted for interventions.

Implications for Interventions

This report has a number of important implications for the design and provision of counseling, supportive services, or other interventions for LGB youths. First, the finding that LGB youths with different levels of identity integration have different levels of psychological adjustment suggests that not all LGB youths may be in need of counseling or clinical services; there are many LGB youths who are doing well or even better than average in their psychological adjustment when compared to their heterosexual peers (see Table 2 for means and comparative normative means on adolescents in the Table’s note). Thus, intervention efforts and therapeutic services may want to target those LGB youths who are experiencing difficulties with their sexual identity integration. Second, the findings that changes in identity integration are associated with differences in psychological adjustment, over and above that accounted for by supportive relationships and experiences of gay-related stress, suggest that interventions and services that focus exclusively on providing a supportive context may not be maximally beneficial for improving the psychological adjustment of some LGB youths. Indeed, the considerable variability in the psychological adjustment of our sample – which was primarily recruited from organizations that provide supportive assistance to LGB youths – suggests that additional issues, such as identity integration, must be addressed to fully understand the youths’ psychological adjustment. Addressing potential barriers to further identity integration may facilitate changes in identity integration and contribute to greater psychological adjustment. This is not to suggest that extant efforts to provide support and ways of coping with gay-related stress are unnecessary, given that past research has found these factors to be associated with psychological adjustment (e.g., Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Rosario et al., 2005; Ueno, 2005). Rather, our findings suggest that issues of identity integration must also be addressed.

Limitations

The study has a number of limitations. First, the sample size was modest, although we had sufficient numbers of cases to detect medium effects. Second, we followed the youths only over one year. Although we found important changes over this short time-frame, we certainly encourage more longitudinal research and over a longer time period. Further, the generalizability of these findings may be limited by the cultural changes in attitudes toward homosexuality and bisexuality that may have occurred since these data were collected. Although more contemporary cohorts may have become more accepting of their sexual identity as a group, those individuals who have difficulty with identity integration may continue to experience poor psychological adjustment. Regardless, we encourage replication of these findings with more contemporary samples of youth. Lastly, and as indicated earlier, our youths were recruited from gay-focused programs; as such, they may differ from LGB youths who do not attend such programs. Despite this limitation, our hypotheses were generally supported and, as previously argued, we expect that findings from more representative samples should be even stronger in magnitude.

Conclusion and General Implications

Our findings underscore the importance of sexual identity development for understanding the adjustment of LGB youths. They suggest that the poor psychological adjustment that has been found among LGB youths relative to heterosexual peers (e.g., Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Fergusson et al., 1999) may be attributed to a subset of youths whose identity integration has stagnated, especially at low levels. Indeed, a comparison of our youths’ anxious and depressive symptoms with adolescent norms for these symptoms (see note in Table 2 for means) indicates that consistently low and middling youths were more symptomatic than normative peers. By comparison, consistently high youths reported lower levels of anxious and depressive symptoms than normative peers. Moreover, the findings held even when the means were adjusted for social context and other covariates. The stronger functioning of youths who were consistently high or decreased from high integration indicates that LGB youths represent a heterogeneous population, with some youths doing quite well as compared with other LGB peers. Therefore, it is essential to understand what explains the within-group differences in order to advance scientific knowledge and eventually design effective interventions to assist those youths whose identity integration is arrested in development.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Center Grant P50-MH43520 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Margaret Rosario, Project PI; Anke Ehrhardt, Center PI).

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Washington DC, November 2007.

Contributor Information

Margaret Rosario, The City University of New York – City College and Graduate Center.

Eric W. Schrimshaw, Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University

Joyce Hunter, HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

References

- Adams GR, Munro B, Doherty-Poirer M, Munro G, Petersen A-MR, Edwards J. Diffuse-avoidance, normative, and informational identity styles: Use of identity theory to predict maladjustment. Identity. 2001;1:307–320. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Archer SL, Grey JA. The sexual domain of identity: Sexual statuses of identity in relation to psychosocial sexual health. Identity. 2009;9:33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Mohr JJ. Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:306–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BE, Brannock JC. Proposed model of lesbian identity development: An empirical examination. Journal of Homosexuality. 1987;14:69–80. doi: 10.1300/J082v14n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. The approval motive: Studies in evaluative dependence. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:433–456. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. A new view of lesbian subtypes: Stable versus fluid identity trajectories over an 8-year period. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Dube EM. The role of sexual behavior in the identification process of gay and bisexual males. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles TA, Sayegh MA, Fortenberry JD, Zimet GD. More normal than not: A qualitative assessment of the developmental experiences of gay male youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:425.e11–525.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. Suicidality among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth: The role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton; 1946/1980. Ego development and historical change; pp. 17–50. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton; 1956/1980. The problem of ego identity; pp. 107–175. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BS, Landau S, Leese M. Cluster analysis. 4. New York: Oxford; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger RE, Miller BA. Validation of an inclusive model of sexual minority identity formation on a sample of gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996;32:53–78. doi: 10.1300/j082v32n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS. Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Kruskal WH. Measures of association for cross classification. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanin JE, Parsons JT. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming-out process among gay, lesbian, bisexual individuals. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:115–121. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley DN. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Kentucky; Lexington KY: 1990. The context of well-being after significant life stress: Measuring social support and obstruction. [Google Scholar]

- Halpin SA, Allen MW. Changes in psychosocial well-being during stages of gay identity development. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47:109–126. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Cluster analysis in family psychology research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:121–132. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger SL, D’Augelli AR. The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Rebchook GM, Kegeles SM. Experiences of harassment, discrimination, and physical violence among young gay and bisexual men. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1200–1203. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igartua KJ, Gill K, Montoro R. Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2003;22:15–30. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KM, Deluty RH. Coming out for lesbian women: Its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;35:41–63. doi: 10.1300/J082v35n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, Fuligni AJ. Multiple social identities and adjustment in young adults from ethnically diverse backgrounds. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:643–670. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J. Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Derlega VJ, Clarke EG, Kuang JC. Stigma consciousness, social constraints, and lesbian well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Maguen D, Floyd FJ, Bakeman R, Armistead L. Developmental milestones and disclosure of sexual orientation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23:219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1966;3:551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Gruen RS. Sexual risk behavior assessment schedule - youth. HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, Pollack L, Canchola J, et al. Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The urban men’s health study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:278–285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr JJ, Fassinger RE. Self-acceptance and self-disclosure of sexual orientation in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: An attachment perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2003;50:482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF. Lesbian coming out as a multidimentional process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1997;33:1–22. doi: 10.1300/J082v33n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JF, Waldo CR, Rothblum ED. A model of predictors and outcomes of outness among lesbian and bisexual women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:61–71. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muise A, Preyde M, Maitland SB, Milhausen RR. Sexual identity and sexual well-being in female heterosexual university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9492-8. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nungesser L. Homosexual acts, actors, and identities. New York: Praeger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Parks CA, Hughes TL. Age differences in lesbian identity development and drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:361–380. doi: 10.1080/10826080601142097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from family: Three validation studies. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1983;11:1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00898416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapkin BD, Luke DA. Cluster analysis in community research: Epistemology and practice. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:247–277. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:133–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predicting different patterns of sexual identity development over time among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A cluster analytic approach. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42:266–282. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Psychological distress following suicidality among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Role of social relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:149–161. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-3213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay-related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:967–975. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. The new gay teenager. Cambridge, MA: Harvard; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29:607–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Rosario M, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Scharf-Matlick AA. Test-retest reliability of self-reported sexual risk behavior, sexual orientation, and sexual development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann SK, Spivey CA. The relationship between self-esteem and lesbian identity during adolescence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2004;21:629–646. [Google Scholar]

- Troiden RR. The formation of homosexual identities. In: Herdt G, editor. Gay and lesbian youth. New York: Haworth; 1989. pp. 43–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BH. Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Udry JR, Chantala K. Risk assessment of adolescents with same-sex relationships. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:84–92. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K. Sexual orientation and psychological distress in adolescence: Examining interpersonal stressors and social support processes. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005;68:258–277. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Fegan MF. Social networks and social support. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Wright ER, Perry BL. Sexual identity distress, social support, and health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;51:81–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]