Abstract

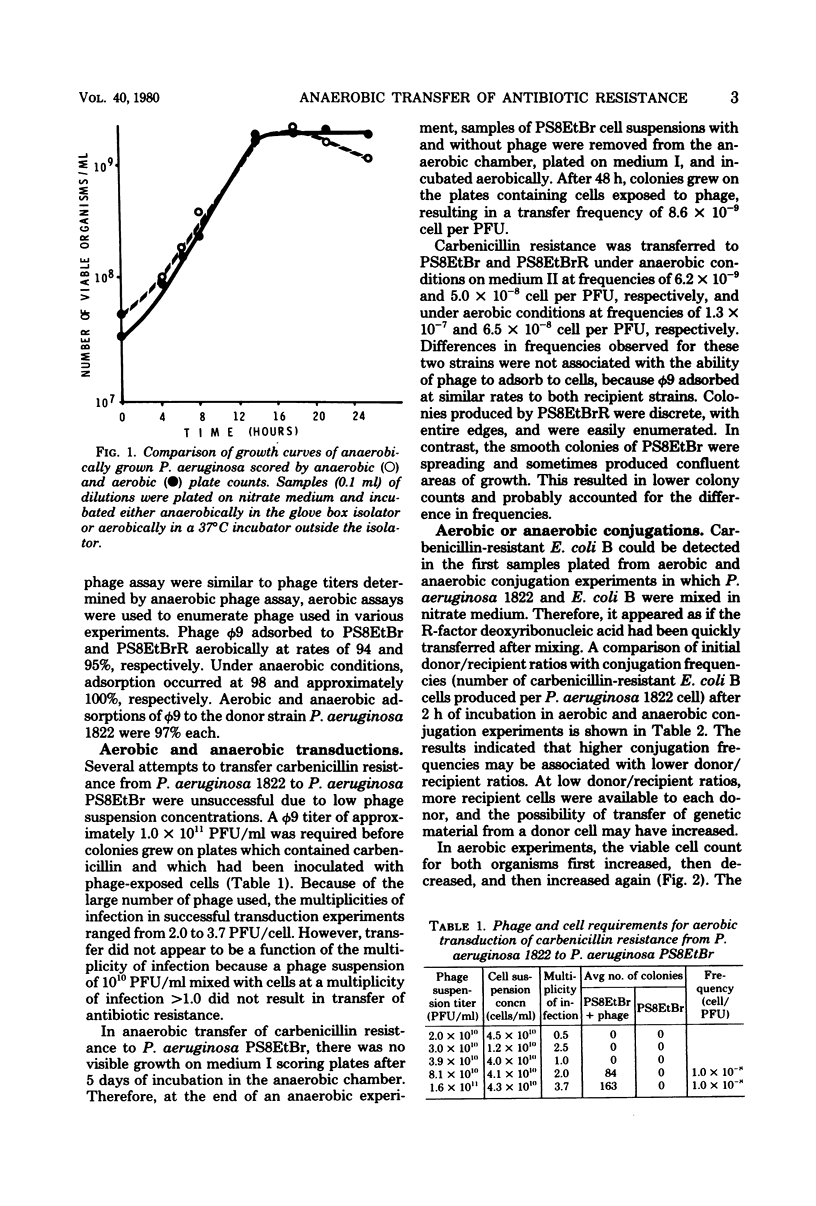

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen that often initiates infections from a reservoir in the intestinal tract, may donate or acquire antibiotic resistance in an anaerobic environment. Only by including nitrate and nitrite in media could antibiotic-resistant and -sensitive strains of P. aeruginosa be cultured in a glove box isolator. These anaerobically grown cells remained sensitive to lytic phage isolated from sewage. After incubation with a phage lysate derived from P. aeruginosa 1822, anaerobic transfer of antibiotic resistance to recipients P. aeruginosa PS8EtBr and PS8EtBrR occurred at frequencies of 6.2 × 10−9 and 5.0 × 10−8 cells per plaque-forming unit, respectively. In experiments performed outside the isolator, transfer frequencies to PS8EtBr and PS8EtBrR were higher, 1.3 × 10−7 and 6.5 × 10−8 cells per plaque-forming unit, respectively. When P. aeruginosa 1822 was incubated aerobically with Escherichia coli B in medium containing nitrate and nitrite, the maximum concentration of carbenicillin-resistant E. coli B reached 25% of the total E. coli B population. This percentage declined to 0.01% of the total E. coli B population when anaerobically grown P. aeruginosa 1822 and E. coli B were combined and incubated in the glove box isolator. The highest concentration of the recipient population converted to antibiotic resistance occurred after 24 h of aerobic incubation, when an initially high donor/recipient ratio (>15) of cells was mixed. These data indicate that transfer of antibiotic resistance either by transduction between Pseudomonas spp. or by conjugation between Pseudomonas sp. and E. coli occurs under strict anaerobic conditions, although at lower frequencies than under aerobic conditions.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aranki A., Freter R. Use of anaerobic glove boxes for the cultivation of strictly anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972 Dec;25(12):1329–1334. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. M., Smith D. D. Resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to carbenicillin. Lancet. 1969 Apr 12;1(7598):753–754. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)91754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger U. Pseudomonas aeruginosa im Darm gesunder Menschen. Zentralbl Bakteriol Orig A. 1975 Dec;233(4):572–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck A. C., Cooke E. M. The fate of ingested Pseudomonas aeruginosa in normal persons. J Med Microbiol. 1969 Nov 4;2(4):521–525. doi: 10.1099/00222615-2-4-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman L. G. Amplification of sex repressor function of one fi-+ R-factor during anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1975 Jul;123(1):265–271. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.1.265-271.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman L. G. Expression of R-plasmid functions during anaerobic growth of an Escherichia coli K-12 host. J Bacteriol. 1977 Jul;131(1):69–75. doi: 10.1128/jb.131.1.69-75.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DARRELL J. H., WAHBA A. H. PYOCINE-TYPING OF HOSPITAL STRAINS OF PSEUDOMONAS PYOCYANEA. J Clin Pathol. 1964 May;17:236–242. doi: 10.1136/jcp.17.3.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEWSON C. A., NICHOLAS D. J. Nitrate reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961 May 13;49:335–349. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinsted J., Saunders J. R., Ingram L. C., Sykes R. B., Richmond M. H. Properties of a R factor which originated in Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1822. J Bacteriol. 1972 May;110(2):529–537. doi: 10.1128/jb.110.2.529-537.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan J. B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa carriage in patients. J Trauma. 1966 Sep;6(5):639–643. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howerton E. E., Kolmen S. N. The intestinal tract as a portal of entry of Pseudomonas in burned rats. J Trauma. 1972 Apr;12(4):335–340. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197204000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knothe H., Krcméry V., Sietzen W., Borst J. Transfer of gentamicin resistance from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains highly resistant to gentamicin and carbenicillin. Chemotherapy. 1973;18(4):229–234. doi: 10.1159/000221266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowbury E. J., Lilly H. A., Kidson A., Ayliffe G. A., Jones R. J. Sensitivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antibiotics: emergence of strains highly resistant to carbenicillin. Lancet. 1969 Aug 30;2(7618):448–452. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90163-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskell P. W., Maley M. P., Hummel R. P. Resistance transfer from Alcaligenes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in burned and unburned germfree mice. Surg Forum. 1976;27(62):69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodie H. L., Woods D. R. Anaerobic R factor transfer in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1973 Jun;76(2):437–440. doi: 10.1099/00221287-76-2-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen R. H., Metcalf E. S. Conversion of mesophilic to psychrophilic bacteria. Science. 1968 Dec 13;162(3859):1288–1289. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3859.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe R. D., Hentges D. J., Barrett J. T., Campbell B. J. Oxygen tolerance of human intestinal anaerobes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977 Nov;30(11):1762–1769. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.11.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELLERS W. MEDIUM FOR DIFFERENTIATING THE GRAM-NEGATIVE, NONFERMENTING BACILLI OF MEDICAL INTEREST. J Bacteriol. 1964 Jan;87:46–48. doi: 10.1128/jb.87.1.46-48.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley P. L., Olsen R. H. Isolation of a nontransmissible antibiotic resistance plasmid by transductional shortening of R factor RP1. J Bacteriol. 1975 Jul;123(1):20–27. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.1.20-27.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shooter R. A., Walker K. A., Williams V. R., Horgan G. M., Parker M. T., Asheshov E. H., Bullimore J. F. Faecal carriage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospital patients. Possible spread from patient to patient. Lancet. 1966 Dec 17;2(7477):1331–1334. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallions D. R., Curtiss R., 3rd Bacterial conjugation under anaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 1972 Jul;111(1):294–295. doi: 10.1128/jb.111.1.294-295.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum S. R., Fett D., Young V. R., Land P. D., Bruce W. R. Nitrite and nitrate are formed by endogenous synthesis in the human intestine. Science. 1978 Jun 30;200(4349):1487–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.663630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch R. A., Jones K. R., Macrina F. L. Transferable lincosamide-macrolide resistance in Bacteroides. Plasmid. 1979 Apr;2(2):261–268. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(79)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMANAKA T., OKUNUKI K. Crystalline Pseudomonas cytochrome oxidase. I. Enzymic properties with special reference to the biological specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1963 Mar 12;67:379–393. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(63)91844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hartingsveldt J., Stouthamer A. H. Properties of a mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa affected in aerobic growth. J Gen Microbiol. 1974 Aug;83(2):303–310. doi: 10.1099/00221287-83-2-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]