Abstract

Malignant melanoma has increased incidence worldwide and causes most skin cancer-related deaths. A few cell surface antigens that can be targets of antitumor immunotherapy have been characterized in melanoma. This is an expanding field because of the ineffectiveness of conventional cancer therapy for the metastatic form of melanoma. In the present work, antimelanoma monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were raised against B16F10 cells (subclone Nex4, grown in murine serum), with novel specificities and antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo. MAb A4 (IgG2ak) recognizes a surface antigen on B16F10-Nex2 cells identified as protocadherin β13. It is cytotoxic in vitro and in vivo to B16F10-Nex2 cells as well as in vitro to human melanoma cell lines. MAb A4M (IgM) strongly reacted with nuclei of permeabilized murine tumor cells, recognizing histone 1. Although it is not cytotoxic in vitro, similarly with mAb A4, mAb A4M significantly reduced the number of lung nodules in mice challenged intravenously with B16F10-Nex2 cells. The VH CDR3 peptide from mAb A4 and VL CDR1 and CDR2 from mAb A4M showed significant cytotoxic activities in vitro, leading tumor cells to apoptosis. A cyclic peptide representing A4 CDR H3 competed with mAb A4 for binding to melanoma cells. MAb A4M CDRs L1 and L2 in addition to the antitumor effect also inhibited angiogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro. As shown in the present work, mAbs A4 and A4M and selected CDR peptides are strong candidates to be developed as drugs for antitumor therapy for invasive melanoma.

Introduction

Malignant melanoma is a deadly cancer of increasing incidence [1]. It is a heterogeneous solid tumor to which conventional therapy (e.g., chemotherapy and radiotherapy) is generally ineffective in its metastatic form [2]. New advances in the understanding of melanoma's microenvironment and the complexity of tumor development and immune response suggest that treatment of this disease may require a combination of procedures. Numerous studies have tested a variety of immunotherapeutic strategies in the treatment of advanced melanoma, including antitumor vaccines, interferon α, interleukin 2 (IL-2), dendritic cells, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and gene therapy [3–7].

The use of mAbs in cancer treatment has increased in the past few years. Originally, murine mAbs performed poorly in the clinic because of their short half-life and immunogenicity in the human host. Chimeric and humanized mAbs have overcome these disadvantages. MAbs are mostly active against membrane-bound target antigens. They can mediate signaling by cross-linking surface antigen that leads to cell death and may alter the cytokine milieu or enhance an active antitumor immune response [8–10]. They may block growth factor receptors, efficiently arresting proliferation of tumor cells [11]. Indirect effects include recruiting cells that exert antitumor antibody (Ab)-dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC), such as natural killer cells and macrophages [12]. MAbs can also bind complement, leading to complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) [12,13]. The adverse effects associated with mAbs depend in part on the distribution of antigenic targets in normal tissues in addition to the intrinsic cytotoxicity of certain Abs. A further use of mAbs is to carry a toxin, cytotoxic agent, or radioisotope, specifically addressing it to the tumor's growing site [14,15]. MAbs can also act to modify the tumor microenvironment by inhibiting angiogenesis and by targeting integrins [16–18]. Several Abs are currently in preclinical and clinical trials to treat malignancies such as renal carcinoma, lymphomas, leukemia, breast, head and neck, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, non-small cell lung, and colorectal cancers [19]. Molecular targets have been human epidermal growth factor receptors (HERs; epidermal growth factor receptor, [EGFR], and HER2), cMET receptor, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and receptor (VEGFR) agents, and integrins α5β1 and αvβ3. Aside from mAbs, a number of small-molecule inhibitors have also been tested in clinical and preclinical trials some already approved by the US Food and Drug Administration [20].

In melanoma, a restricted number of mAbs have been described with some success in tumor regression in clinical trials but with toxic adverse effects. In vitro studies have shown that mAb R24, a mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) that recognizes the ganglioside GD3 [21], had specific antimelanoma properties. R24 binding to GD3 mediated ADCC as well as CDC, and infusion of R24 in patients with metastatic melanoma showed remarkable tumor regression in some of them [22]. Unfortunately, dose-dependent adverse effects restricted further use of mAb R24 [23]. To overcome the immunological tolerance to melanoma, a human anti-CTLA4 mAb, ipilimumab, is being tested as monotherapy and in combination with vaccines, IL-2, and dacarbazine. Overall response rates ranged from 13% to 22% in patients with stage IV metastatic disease [24]. Preclinical studies with a fully human Ab against melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM/MUC18) have also shown promising results [25–27]. This Ab (ABX-MA1) had no effect on melanoma cell proliferation in vitro. However, it significantly inhibited tumor growth of metastatic melanoma cell lines injected subcutaneously in nude mice. ABX-MA1 treatment also suppressed lung metastasis of these melanoma cells [27]. MAbs represent, therefore, another modality to treat melanoma either alone or in combination with conventional chemotherapy or other antitumor agents.

Another approach in the immunotherapy of cancer patients involves peptides [28]. Peptides can be derived from tumor-associated antigens and be used to enhance the host immune response through interactions with and activation of T cells [29,30]. Further improvement of peptide vaccination, including the use of adjuvants, peptidepulsed dendritic cells, multipeptide vaccination, addition of helper peptides, and peptide expression through the use of mini genes have made progress in the past few years [28,30–32]. Peptides can be synthesized with posttranslational modifications or protease-resistant peptide bonds to increase their stability in vivo [33]. Apart from immune peptides, there also are reports on the direct binding of peptides to tumor cells causing inhibition of tumor growth and killing cells by apoptosis. Antimicrobial peptides only in a few cases display antitumor activity [34]. Nevertheless, we showed that gomesin was cytotoxic to B16F10-Nex2 cells and human tumor cells in vitro. Topical treatment with gomesin of subcutaneously grafted melanoma in mice significantly reduced tumor growth [35].

Polonelli et al. [36] introduced the concept that short synthetic peptides corresponding to the sequences of immunoglobulin complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) may display antimicrobial, antiviral and antitumor activities regardless of the Ab specificity for a particular antigen. The high frequency of bioactive peptides based on CDRs suggests that Ig molecules could be sources of unlimited number of sequences potentially active against infectious agents and tumor cells.

Previously, we have shown that a murine mAb (A4) raised against B16F10 tumor cells was cytotoxic in vitro in a complement-mediated reaction and effectively thwarted tumor development in syngeneic mice [37]. A second antimelanoma mAb (A4M) was characterized, and in the present work, we describe their targets on tumor cells. Both mAbs significantly inhibited lung metastases, although only mAb A4 induced apoptosis of tumor cells in vitro. CDR peptides derived from both Abs also showed cytotoxicity against tumor cells. VH CDR3-derived cyclic peptides from both mAbs showed characteristics of micro-Abs, including antitumor apoptotic activity in the case of mAb A4 H3.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Reagents

The following cell lineswere used in the present work: B16F10-Nex2, a subclone of B16F10 cell line originally obtained from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo branch; human melanoma cell lines (SKmel25, SKmel28, and Mel85); human umbilical vein endothelial cell line (HUVEC); human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) and its transgenic mutants (Bcr-Abl, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL); hybridoma A4, raised against B16F10-Nex4 cells (in vitro cultured in murine serum-supplemented medium) as previously described [38]; and hybridoma A4M, isolated by subcloning A4 hybridoma. All cell lines and hybridomas were maintained in culture in RPMI 1640 medium pH 7.2, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N-2-ethanesulphonic acid), and 24 mM NaHCO3, all from Gibco (Minneapolis, MN), and with 40 mg/L gentamicin sulfate (Hipolabor Farmacêutica, Belo Horizonte, Brazil). Murine anti-pan-histone Abs were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany).

Monoclonal Antibodies and CDR-Based Synthetic Peptides

Hybridomas A4 and A4M were inoculated in pristane-inflamed peritoneum of nude female mice, and mAbs-containing ascites were collected. MAb A4 was purified as previously described [37], and mAb A4M was purified on Sephacryl S200 (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden) as described by Bouvet et al. [38]. Peptides based on CDR sequences of mAb A4 and mAb A4M were synthesized by the solidphase and classic solution methods of peptide synthesis [39]. All the obtained peptides were purified by semipreparative HPLC on an Econosil C-18 column. The molecular mass and purity of synthesized peptides (≥ 94%) were checked by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometry, using TofSpec-E (Micromass, Manchester, UK). Irrelevant IgG 2a (17D) and IgM (1G6) mAbs, both raised against fungal (Paracoccidioides) antigens, were used as isotype controls.

Western Blot Analysis

B16F10-Nex2 total lysate (1 x 107 cells) was separated in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon P transfer membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, with Tween-20 (0.02%; PBS-T), and were blocked with 5% skimmed milk (Molico; Nestle, São Paulo, Brazil) in PBS-T overnight (ON) at 4°C. The blots were then probed ON at 4°C with mAb A4, A4M, or anti-pan-histone Abs. After 1 hour of incubation with anti-IgGor anti-IgM secondary Ab (1:2000) followed by 1 hour incubation with streptavidin-peroxidase, immunoreactive proteins were detected by chemiluminescent ELISA (CL-ELISA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (ECL detection system; Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA). B16F10 nuclear extraction and histone detection by Western blot analysis were followed as previously described [35].

Immunoprecipitation

B16F10-Nex2 cells (1 x 108) were washed twice in PBS and lysed using lysis buffer (0.9% NaCl [Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ], 0.01 M Tris-HCl [Gibco], pH 7.2, 0.01 M MgCl2 [Merck], 0.2 M PMSF [Gibco], and 0.5% NP-40 [LKB-Produkter, Bromma, Sweden]). Total cell lysate (500 µg of protein) was incubated with 100 µg/ml of mAb A4 at 4°C ON on an orbital shaker. Protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) was added (500 µl) to the sample and incubated at 4°C ON with shaking. Sample was collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C and washed twice with PBS-T and once with PBS. Proteins were dissolved in SDS gel loading buffer and subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE.

Protein Identification by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Immunoprecipitated sample was digested with trypsin as described by Stone and Williams [40]. Briefly, the samples were dissolved in 40 µl of 400 mM NH4HCO3 containing 8 Murea, and the disulfide bonds were reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol for 15 minutes at 50°C. Cysteine residues were then alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT). The reaction was diluted eight-fold, and 4 µg of trypsin (sequencing grade; Promega, Madison, WI) was added and incubated ON at 37°C. The digestion was terminated with 1 µl of formic acid (FA), submitted to desalting using POROS R2 ziptips, as described elsewhere, and dried in a speed vac (Vacufuge; Eppendorf, Westbury, NY) [41].

Samples were redissolved in 20 µl of 0.1%FA, and 8 µl was loaded on a C18 trap column (0.25 µl; OptiPak, Oregon City, OR) coupled to a nano-HPLC system (1D-plus; Eksigent, Dublin, CA). After washing for 10 minutes with 2% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1% FA in a flow rate of 5 µl/min, peptides were separated in a capillary reverse phase column (15 cm x 75 µm, 3-µm spheres; ProteoPep 2 [New Objective, Woburn, MA]). A gradient was set with 5% to 40% solvent B for 100 minutes (solvent A:2%ACN/0.1% FA; solvent B: 80% ACN/0.1% FA) in a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Peptides eluted were analyzed online in a linear trap mass spectrometer (LTQXL with ETD; Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The 10 most abundant peaks were submitted to collision-induced dissociation (35% normalized collision energy) twice before being dynamically excluded for 2 minutes.

The MS/MS spectra of peptides from 600 to 4000 Da were converted to DTA using Bioworks (version 3.3.1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a threshold of 100 counts and 15 fragments. The spectra were searched against a database assembled with the mouse IPI (v3.25, downloaded on January 17, 2007, from http://www.ebi.ac.uk/IPI/IPImouse.html) and common contaminants (trypsin and keratin, downloaded on May 30, 2007, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=Protein&itool=toolbar) sequences, using Sequest, (Thermo, Finnigan, San Jose, CA) [42]. All the sequences were set in the correct and inverse orientation forming, a database with a total of 104,850 sequences. The parameters of the database search were 2 Da for peptide mass tolerance, cysteine carbamidomethylation (fixed modification), methionine oxidation (variable modification), and a maximum of one missed cleaved site for trypsin digestion. The false-positive rate was calculated to be 1.2%to 2.9% depending on the data set after applying the following filters: DCn > 0.1; Xcorr > 1.5, 2.2, 2.7 for singly, doubly, and triply charged peptides, respectively; distinct peptides; and a protein probability < 1e-3.

Confocal Microscopy

B16F10-Nex2 cells (2 x 103) were cultivated on round glass coverslips (13 mm) for 24 hours after fixation with 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 minutes at RT. Cells were then incubated with block solution (150 mM NaCl [Merck], 50 mM Tris [Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA], 0.25% bovine serum albumin [BSA; Sigma, St Louis, MO], and 0.5% Tween-20 [Sigma], pH 7.2) for 1 hour at RT. A4M or anti-pan-histone Abs (5 mg/ml) were incubated for 12 hours at 4°C. After several washes in PBS, biotinylated antimouse IgM or antimouse IgG (1:500; Sigma) were incubated at RT for 1 hour after incubating with streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; 1:250; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Alternatively, antimouse IgG rhodamine conjugate (1:250) was used to colocalize histones in the tumor cells. Staining of actin filaments and nuclei was performed with 0.3 µg/ml phalloidinrhodamine conjugate (Invitrogen) and 50 µg/ml 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI; Invitrogen), respectively, for 1 hour at RT. To remove histones from tumor cells, coverslips coated with B16F10 cells were previously treated with 0.4N sulfuric acid for 30 minutes on ice. After several washes in PBS, the reaction was carried out as described above. The coverslips were treated with a mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to reduce bleaching and were examined by laser scanning fluorescence confocal microscope (MRC 1024/UV System; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) equipped with a transmitted light detector for Nomarski differential interference contrast. The images were obtained with a 40x 1.2NA/water immersion PlanApo objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc, Thornwood, NY); Kalman averaging at least 20 frames using a 2-mm iris (pinhole).

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Analysis

MAbs or CDR peptides (linear or cyclic) were diluted in supplemented RPMI medium at different concentrations and incubated with 5 x 103 B16F10-Nex2 or human tumor cells in 96-well plates; cells were plated 24 hours before treatment. After ON incubation at 37°C, viable cells were counted in a Neubauer chamber (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) using Trypan blue. Alternatively, cell proliferation was measured using the Cell Proliferation Kit I (MTT; Boehringer Mannheim), an MTT-based colorimetric assay for quantification of cell proliferation and viability. Readings were made in an ELISA plate reader at 570 nm. Values are indicated as mean percentage variation of cell death and normalized to control. Each assay was performed in triplicate. Similar results were obtained in at least three independent experiments.

DNA Fragmentation Assay

B16F10-Nex2 cells as well as humanmelanoma cell lines were grown for 24 hours in 12-well plates (105 cells/well) and were then further incubated for 12 hours at 37°C with either the mAb A4 (100 µg/ml) or the synthetic CDR peptides (0.1 mM of A4 H3, 0.8 mM of A4M L1, and 0.6 mM of A4M L2). The DNA extraction and fragmentation analyses were carried out as previously described [36].

Apoptosis/Necrosis Detection

B16F10-Nex2 cells were grown for 24 hours in a six-well plate (5 x 105 cells/well) and further incubated with mAb A4 (100 µg/ml) for 6 and 12 hours at 37°C. For negative control, cells were incubated with irrelevant Ab at the same concentration. As positive control, cells were incubated with cisplatin at a final concentration of 400 µM per well. At the end, cells were harvested with cold PBS after three washes in the same buffer. Apoptotic/necrotic cells were detected using the ApoScreen Annexin V-FITC kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). All experiments were conducted in triplicate. A representative picture is shown.

Cytofluorometric Analyses of Propidium Iodide Staining

The HL-60 cells were plated at 2 x 105/well in a six-well plate and incubated with CDR peptides at different concentrations for 12 hours or a fixed concentration (0.5 mM) and variable periods at 37°C. Cytofluorometric analyses of propidium iodide staining were performed according to Nicoletti et al. [43]. Briefly, both detached and attached cells were collected and incubated in a hypotonic fluorochrome solution (propidium iodide 50 µg/ml in 0.1% sodium citrate plus 0.1% Triton X-100). The propidium iodide fluorescence of each sample was analyzed by flow cytometry (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Alternatively, HL-60 transgenic variants overexpressing antiapoptotic molecules such as Bcr-Abl, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL were treated with CDR peptides at 0.5 mM for 12 hours and analyzed as described above. Each sample was carried out in triplicates. Five individual experiments were analyzed.

In Vitro Angiogenesis Assay on Matrigel

The assay was prepared as previously described [44]. Briefly, BD Matrigel Matrix (BD Biosciences) was distributed in 96-well plates and allowed to polymerize for 1 hour at 37°C. The HUVEC cells (5 x 103 cells/well) were suspended in 100 µl of RPMI medium supplemented with 0.2% of fetal calf serum in addition to the synthetic CDR peptides. The samples were added to each well and allowed to grow at 37°C for 18 hours. Images were captured at 8x magnification with a Sony (New York, NY) Cybershot camera coupled to a light inverted microscope. The number of proangiogenic structures (closed rings formed by intercellular projections) was counted from four different wells, and the average value was determined for each sample. As a control of the assay, HUVEC cells were plated on Matrigel without peptide addition.

Chemiluminescent-ELISA

CL-ELISA was carried out as previously described [37]. Briefly, B16F10-Nex2 cells (104 cells/well) were fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 12 hours at 4°C in a white opaque ELISA plate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). After blocking with 1% BSA in PBS, 0.05% Tween 20 (BPT), purified mAbs A4 and A4M were incubated for 12 hours at 4°C. Biotinylated antimouse IgG or IgM (Sigma) and streptavidin-peroxidase (Sigma) were added at a dilution of 1:1000 in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, after incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes with gentle shaking. After several washes in BPT buffer, the reaction was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence using the ECL detection system following the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare Lifesciences, Piscataway, NJ). The chemiluminescence readings were obtained in a microplate luminometer (Cambridge Technology, Watertown, MA) and expressed as relative luminescent units. Alternatively, for the binding competition assay, synthetic CDR peptides were previously incubated at different concentrations with B16F10-Nex2-coated plates for 12 hours at 4°C. After several washes in BPT buffer, mAb A4 or A4M was added in triplicates at 10 µg/ml per well and further incubated for 12 hours at 4°C. The reaction was developed as described above.

Flow Cytometry (FACS)

B16F10-Nex2 cells (106/Eppendorf tube) were incubated with permeabilization buffer (PBS, pH 7.2, 0.5% saponin, 1% paraformaldehyde) for 20 minutes at 4°C. After several washes in PBS-saponin 0.5% (PBSs), CDR cyclic peptides (VH cCDR3) derived from both mAb A4 and mAb A4M were added at three different concentrations (50, 10, and 1 µg per sample) for 1 hour at 4°C. After three washes in PBSs followed by blocking (1% BSA, PBSs), each sample was incubated with 10 µg/ml of the corresponding mAb for 1 hour at 4°C. Addition of the secondary Ab and data analysis were done as previously described. As negative control, cells were incubated only with the secondary Ab. For positive control, samples were treated with mAbs without peptide addition.

Animals, Tumor Growth, and Metastasis

Inbred male 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Centro de Desenvolvimento de Modelos Experimentais at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of UNIFESP. Subcutaneous tumors were produced by injecting 5 x 104 B16F10-Nex2 cells (single-cell suspensions, >95% viability by Trypan blue exclusion test) in 0.1 ml of serum-free RPMI medium into the right flank of each mouse (five animals per group). Five days after challenge, the experimental group was treated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with mAb A4 (500 µg per mouse) and subsequent 100-µg doses after 7 days for 3 weeks. Tumor growth was recorded three times weekly with a caliper, and the survival of challenged animals was scored and statistically analyzed. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula: V = 0.52 x D12 x D3, where D1 and D3 are the short and long tumor diameters, respectively. Maximal volumes of 3 cm3 were allowed before killing. For experimental lung metastasis assay, 5 x 105 tumor cells, processed as described above, were injected into the tail veins of mice (0.1 ml per mouse). Five days after challenge, the experimental group was treated i.p. either with mAb A4 or with mAb A4M (500 µg per mouse) followed by a single i.p. administration of 100 µg of mAb A4 or A4M after 7 days. Twenty days later, animals were killed, their lungs were harvested, and the number of macroscopic surface tumor nodules was counted. Five mice were used in each group. Administration of an irrelevant Ab of same isotype was used as a negative control.

Statistical Analysis

Significant differences were assessed using Student's t test. All experiments were conducted two or more times. Reproducible results were obtained, and representative data are shown. The survival plots were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier log-rank test. In both tests, the differences were considered statistically significant when P < .05.

Results

MAb A4 and mAb A4M React with B16F10-Nex2 Cells

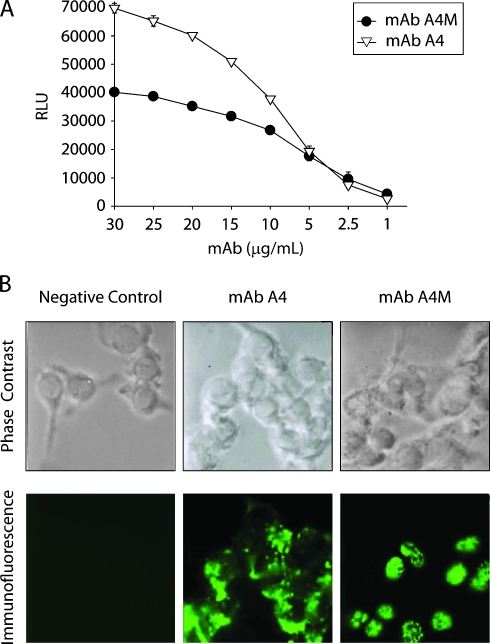

MAb A4 (IgG2ak) was obtained as previously described by immunization with whole B16F10-Nex4 cells grown in murine serum and mixed with Alum [37]. Subcloning of the hybridoma disclosed a second clone expressing mAb A4M (IgM). Both mAbs A4 and A4M strongly reacted with B16F10-Nex2 cells in a dose-dependent manner as shown by CL-ELISA (Figure 1A). Binding of mAb A4M was less intense than that of mAb A4.

Figure 1.

Reactivity of mAb A4 and mAb A4M with B16F10-Nex2 tumor cells. (A) mAb binding to melanoma cells evaluated in CLELISA. (B) Immunofluorescence of B16F10-Nex2 cells with mAb A4 and mAb A4M. Negative control, melanoma cells incubated with anti-Ig FITC alone.

Immunofluorescence assay showed that mAb A4M reacted mainly with nuclei of B16F10-Nex2 cells, whereas mAb A4 strongly reacted with components on the cell surface and cytoplasm of tumor cells (Figure 1B). As previously shown, mAb A4 recognizes a mimetope of melibiose. In contrast, binding of mAb A4M was not inhibited by any carbohydrate tested (data not shown). Also, both Abs bound to different peptides of a phage displayed a library of 9 to 12 aa peptides, showing that they indeed have different specificities (data not shown).

MAb A4 Induces Apoptosis in Melanoma Cell Lines through Binding to Protocadherin β13

We have shown that mAb A4 was cytotoxic to B16F10-Nex2 cells in vitro, independent of complement. Cytotoxic assays were also run without complement using three human melanoma cell lines (SKmel25, SKmel28, and Mel85). MAb A4 significantly reduced the cell viability of these cells by 50% at 15 µg/well compared with nontreated cells (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

MAb A4 is cytotoxic in melanoma cell lines. (A) Inhibitory mAb A4 effect against human melanoma cell lines in the absence of complement. Cell viability was measured by MTT. Data are shown as mean percentage variation of cell death normalized to control. Control, cells incubated with an irrelevant antibody at 20 µg/well; *P < .001. (B) MAb A4 induced DNA degradation in B16F10-Nex2 and human melanoma cell lines. STD, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder; Ctrl, cells incubated with irrelevant antibody at the same concentration. (C) B16F10-Nex2 cells were treated with mAb A4, cisplatin, or an irrelevant antibody as described in Materials and Methods for 6 and 12 hours. Increased numbers of Annexin and propidium iodide (PI) double-positive cells were observed after mAb A4 and cisplatin incubation.

Interestingly, mAb A4 treatment in vitro led to substantial morphological changes in tumor cells such as cell blebbing, shrinkage, and loss of adherence. B16F10-Nex2, SKmel28, and Mel85 cells were then incubated with mAb A4, and DNA fragmentation was observed after 12 hours, suggesting the induction of apoptosis (Figure 2B). After treating with mAb A4 for 6 and 12 hours, adherent and detached B16F10-Nex2 cells were harvested and further analyzed by flow cytometry for Annexin V binding and propidium iodide incorporation. As depicted in Figure 2C, cells treated with mAb A4 for 12 hours had a twofold increase in double-positive cells compared with the negative control (48% and 23%, respectively). Such reactivity was similar to cisplatin treatment and showed that detached melanoma cells rapidly evolved from an apoptotic to necrotic stage incorporating propidium iodide.

To identify the mAb A4 ligand on melanoma cells, Western blot analysis was carried out using B16F10-Nex2 total lysate. MAb A4 recognized a protein of 87 kDa as seen in Figure 3A (WB). The immunoprecipitated sample with mAb A4 (Figure 3A, IP) was digested with trypsin and analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). After removing the hits from a sample immunoprecipitated by a control Ab and Ab sequences, we found only nine candidates for the antigen recognized by mAb A4: cytochrome P450 2A5 (IPI: IPI00123964.1), elongation factor 1-α1 (IPI00307837.5), elongation factor 1-α2 (IPI00119667.1), glycerol kinase-like protein 2 (IPI00123975.1), Golgi autoantigen (IPI00753818.1), l-lactate dehydrogenase B chain (IPI00229510.4), LOC544907 protein (IPI00462354.1), myeloid cysteine-rich protein (IPI00408687.1), and protocadherin β13 (IPI00129344.1; Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

MAb A4 recognizes protocadherin β13 on melanoma cells. (A) TL of B16F10-Nex2 was examined for reactivity with mAb A4. TL, a band at 87 kDa was seen on SDS-PAGE; WB, a protein of identical molecular mass was recognized by mAb A4 in Western blot analysis; IP, the 87-kDa component was immunoprecipitated by mAb. (B) A mAb A4-immunoprecipitated sample was analyzed by LC-MS/MS, and the peptide shown underlined in bold italic and below was fully identified, being a characteristic of protocadherin β13 (complete sequence shown, 796 aa, calculated mol. wt. = 87,458).

The latter was the only molecule that matched the antigen molecular mass of 87 kDa recognized by mAb A4. A very well characterized peptide, QYLQLDPQTQDLMLNENLDR, was found at 72 to 91 in the 796-aa protocadherin β13 glycoprotein. Murine and human surface-expressed protocadherin-β one-exon gene families show a high evolutionary conservation [45].

MAb A4M Recognizes Histone 1 in B16F10 Cells

MAb A4M strongly reacted with nuclei of B16F10-Nex2 cells, which is consistent with its lack of cytotoxicity to whole tumor cells in vitro with or without complement (not shown). Immunoblot analysis using B16F10-Nex2 nuclear extracts revealed that mAb A4M recognized a single protein band at 32 kDa corresponding to histone 1 (Figure 4A). To confirm mAb A4M specificity, we compared its reactivity with that of a commercial anti-histone 1 Ab. Both Abs reacted with purified calf thymus histone (H1; Sigma). Antihistone reactivities of both Abs were abolished after acid depletion of histones from B16F10- Nex2 nuclei (Figure 4B). Moreover, mAb A4M colocalized to the nucleus with antihistone Ab (Figure 4B, lower panel).

Figure 4.

MAb A4M reacts with histone 1 in B16F10-Nex2 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of B16F10-Nex2 nuclear extract (NE) and H1 commercially purified calf thymus histone (Sigma) with mAb A4M and anti-pan-histone antibody. Negative control, with irrelevant mAb. (B) Confocal microscopy showing the mAb A4M reactivity on the nuclei of B16F10-Nex2 cells compared with antihistone antibody. Cells untreated (Histone +) and treated with sulfuric acid to remove histones (Histone -) are compared. Bottom panel: Colocalization of mAb A4M and antihistone reactions (MERGE). Red indicates phalloidin-rhodamine; blue, DAPI staining.

MAbs A4 and A4M Inhibit Tumor Growth and Metastases In Vivo

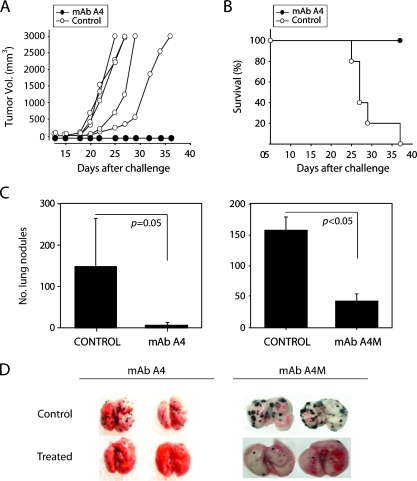

Mice challenged subcutaneously with B16F10-Nex2 cells were treated with mAb A4. As depicted in Figure 5A, treatment with mAb A4 rendered full protection against tumor growth (n = 5). All mAbtreated animals were alive 40 days after challenge compared with none in the untreated group (P < .001; Figure 5B). MAb A4M was ineffective in the same conditions (not shown). We then evaluated the capacity of both A4 and A4M mAbs to inhibit metastases of melanoma cells. Mice were injected intravenously with B16F10-Nex2 cells and treated i.p. with mAbs A4 or A4M. A very significant reduction in the number of lung metastases was seen with both mAbs (mean values: A4 = 10, control = 150, P = .05; mAb A4M = 45, control = 155, P < .05; Figure 5, C and D).

Figure 5.

Antitumor effects of mAb A4 and mAb A4M. (A) MAb A4 injected i.p. led to inhibition of B16F10-Nex2 subcutaneous tumor growth (black circles, n = 5). Controls, animals injected i.p. with irrelevant antibody (white circles, n = 5). (B) Survival record of both groups treated with mAb A4 and the control group (P < .001). (C) Effect of the mAb A4 and mAb A4M-treatment on experimental lung metastases showing a significant decrease in their number with both mAbs (P = .05 and P < .05, respectively). (D) Representative lungs from control and mAb-treated animals after 25 days of intravenous tumor challenge. Control, animals treated with irrelevant antibody at the same concentration.

Synthetic Peptides On the Basis of the CDRs of mAb A4 and mAb A4M Induce DNA Degradation and Inhibit Cell Proliferation In Vitro

We have shown that synthetic CDR-related peptides derived from Abs with different specificities could display antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo [36]. Presently, we examined the antitumor effects of CDRs from both mAbs A4 and A4M. Synthetic peptides corresponding to the CDRs 1 to 3 of VL and 1 and 2 of VH were tested in the linear form after Kabat's rules for their localization and size. CDR3 of VH from both A4 and A4M were tested in the linear configuration and in a cyclic-extended form [46,47]. All sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

CDR Sequences of mAb A4 and mAb A4M.

| CDR | mAb A4 | mAb A4M |

| H1 | DFAMS | EYTIH |

| H2 | YISSAGSYIDYADTV | WFYPGSGSIKYNEKF |

| H3 | IRDGHYGSTSHWYF | ARHEGRGWDYF |

| Cyclic H3 | CIRDGHYGSTSHWYFDVWGC | CARHEGRGWDYFDYWGC |

| L1 | TATSSVSSSYLH | RASGNIHNYLA |

| L2 | STSNLAS | NVKTLA |

| L3 | HQYHRSPP | QHFWSTPL |

Italic: Cysteine added to obtain the cyclic peptide.

Underlined: Extended sequences as described by Morea et al. [48].

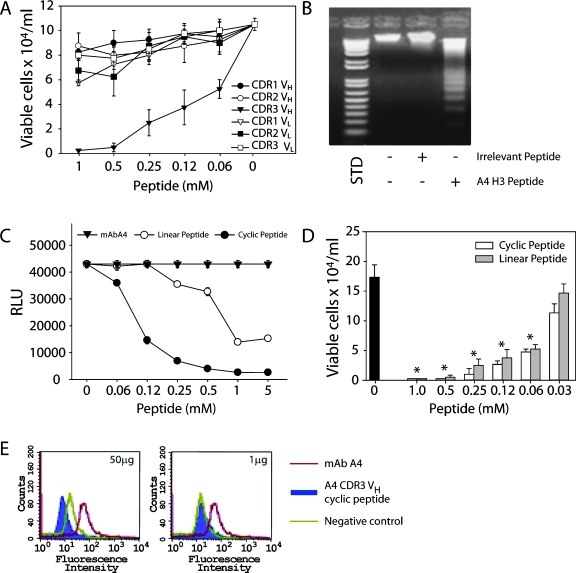

All CDRs from mAb A4 were screened in vitro against B16F10 cells. Interestingly, only mAb A4 CDR H3 was cytotoxic to B16F10 cells, inhibiting 50% of tumor cell growth at 0.06 mM (Figure 6A and Table 2). Moreover, it led melanoma cells to apoptosis in vitro, inducing DNA degradation (Figure 6B). The possibility that A4 CDR H3 might act as a micro-Ab with several functional characteristics of the original mAb was initially tested in CL-ELISA. As seen in Figure 6C, the addition of the cyclic-extended form of A4 CDR H3 significantly inhibited the mAb A4 binding to melanoma cells. The linear A4 CDR H3 peptide was also inhibitory, but it was less active than the cyclic peptide. Both cyclic and linear A4 CDR H3 peptides were cytotoxic to B16F10-Nex2 cells, dramatically reducing the cell viability in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6D). In addition, FACS analyses revealed that the cyclic A4 CDR H3 competed with mAb A4 for binding to the same antigen on B16F10-Nex2 cells, with 100% inhibition of mAb A4 binding at 50 µg of peptide (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

MAb A4 VH CDR3 (H3) peptide is the only inhibitory CDR of mAb A4 (A). A4 H3 peptide induces DNA degradation in B16F10- Nex2 cells (B). STD, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (Invitrogen). (C) Cyclic-extended and linear mAb A4 H3 peptides were tested for competition with mAb A4 in CL-ELISA. Peptides were incubated with tumor cells previously to addition of mAb A4 as described in Materials and Methods. (D) In vitro titration of cytotoxic effects of cyclic and linear mAb A4 H3 in B16F10-Nex2 cells. Black bar, untreated cells (*P < .001). (E) Addition of cyclic-extended mAb A4 H3 peptide (50 µg) abrogates mAb A4 binding to B16F10-Nex2 cells (blue peak). Negative control, cells incubated with anti-IgG FITC alone. Positive control, mAb A4 alone (red peak).

Table 2.

In Vitro Antitumor Activity of Synthetic mAb A4 CDR H3 and of mAb A4M CDRs L1 and L2 and Their Alanine-Substituted Derivatives (asd) against B16F10-Nex2 Melanoma Cells.

| CDR | EC50 (95% CI), M | |

| A4 H3 | 6.00 (4.117–7.883) x 10-5 | |

| A4M L1 | 11.1 (10.222-11.978) x 10-4 | |

| A4M L2 | 26.1 (22.304–29.896) x 10-5 | |

| mAb A4M L1 asd | EC50 (95% CI), M | EC50asd/EC50L1 |

| L1 R1A | 12.2 (11.327–13.073) x 10-4 | 1.09 |

| L1 S3A | 12.2 (10.041–14.359) x 10-4 | 1.09 |

| L1 G4A | 13.5 (12.182–14.808) x 10-4 | 1.21 |

| L1 N5A | 10.8 (9.923–11.677) x 10-4 | 0.97 |

| L1 I6A | 13.5 (11.743–15.257) x 10-4 | 1.21 |

| L1 H7A | 11.5 (10.622–12.378) x 10-4 | 1.03 |

| L1 N8A | 11.1 (10.661–11.539) x 10-4 | 1.00 |

| L1 Y9A | 620 (616.08–623.92) x 10-4 | 55.85 |

| L1 L10A | 621 (619.57–620.43) x 10-4 | 55.94 |

| mAb A4M L2 asd EC50 (95% CI), M | EC50asd/EC50L2 | |

| L2 N1A | 1388.0 (1378.0-1398.0) x 10-5 | 53.38 |

| L2 V2A | 41.6 (40.166-43.034) x 10-5 | 1.59 |

| L2 K3A | 163.0 (155.41–170.59) x 10-5 | 6.25 |

| L2 T4A | 2500.0 (2482.1–2517.9) x 10-5 | 95.78 |

| L2 L5A | 49.0 (37.525–60.475) x 10-5 | 1.87 |

CI indicates confidence interval.

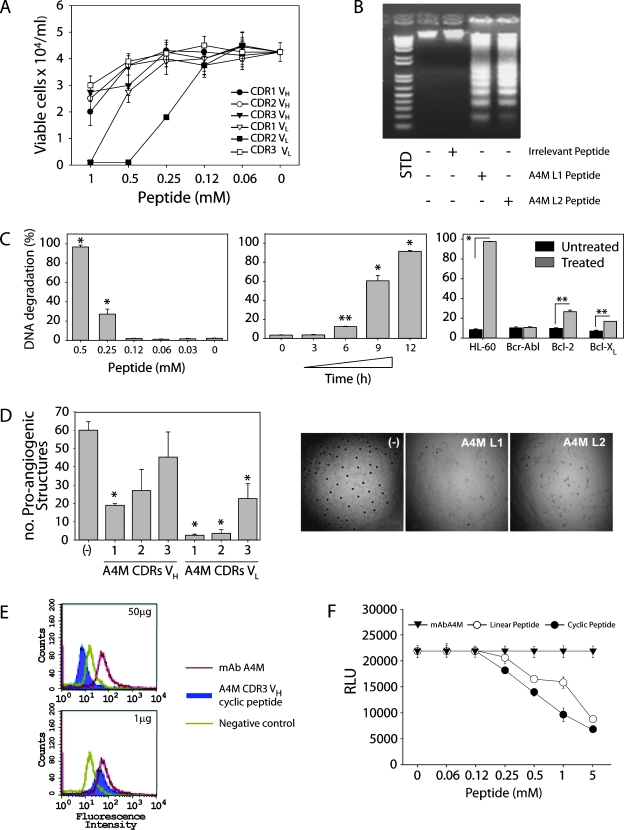

Likewise, CDR peptides derived from the mAb A4M were tested against B16F10-Nex2 cells in vitro (Figure 7A). Two CDR peptides, L1 and L2, were found to inhibit the tumor cell growth by 50% at 1.1 and 0.26 mM, respectively (Table 2). Alanine substitutions in the A4M CDR L1 peptide at the C-terminus (tyrosine and leucine residues) revealed that this region is essential for the cytotoxic activity. For the shorter A4M CDR L2 peptide, alanine substitutions of asparagine and mainly of threonine at positions 1 and 4 significantly reduced the cytotoxic activity of the CDR (Table 2).

Figure 7.

MAb A4M VL CDR1 and 2 (L1, L2) are cytotoxic to B16F10-Nex2 melanoma cells (A) and induce DNA degradation in these cells (B). STD, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder. In human leukemia HL-60 cells, mAb A4M L2 peptide induces a dose- and time-dependent DNA degradation, which is blocked in HL-60 cells overexpressing antiapoptotic molecules (*P < .001, **P < .01) (C). Inhibition by mAb A4M CDRs L1 and L2 of HUVEC sprouting on Matrigel to form closed proangiogenic structures; *P < .001 relative to untreated control (-) (D). The mAb A4M cyclic-extended H3 inhibited mAb A4M binding to B16F10-Nex2 as shown by FACS (E) and by CL-ELISA (F). Negative control, cells incubated only with anti-IgM FITC. Positive control, mAb A4M alone (red).

Further experiments showed that A4M CDR L1 and L2 induced DNA degradation in B16F10-Nex2 cells (Figure 7B), suggesting that these peptides could also trigger apoptosis in tumor cells. Additional experiments using HL-60 leukemia cells and A4M CDR L2 revealed typical apoptotic alterations including surface blebs and nuclear fragmentation (data not shown). Furthermore, the DNA degradation was dose- and time-dependent (Figure 7C). When HL-60 cells overexpressing antiapoptotic molecules such as Bcr-Abl, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL were used, the L2 peptide cytotoxicity (DNA degradation) was considerably inhibited (Figure 7C).

Because angiogenesis is another important therapeutic target for cancer treatment, we also tested A4M CDR peptides for the inhibition of endothelial cell (HUVEC) sprouting in Matrigel. The mAb A4M CDRs L1 and L2 and, less intensely, H1 and L3 significantly inhibited endothelial cell sprouting and intercellular connections in the 60% to 90% range (P < .001; Figure 7D).

Although cytotoxicity against B16F10-Nex2 cells was observed with L1 and L2 CDRs from mAb A4M, the Ab itself was not cytotoxic to whole tumor cells in vitro, indicating different mechanisms of action and binding properties of these agents. The A4M CDR H3 was not cytotoxic per se but was able to compete with mAb A4M for binding to melanoma cells. The cyclic form of A4M CDR H3 peptide inhibited mAb A4M binding to tumor cells as seen by FACS (Figure 7E) and by CL-ELISA where linear and cyclic forms of mAb A4M H3 inhibited Ab binding (Figure 7F). Thus, for mAbs A4 and A4M, H3 CDRs played roles of micro-Abs, representing an essential part of Ab-antigen recognition and, in some cases, displaying similar functional activities.

Discussion

Antibodies directed to tumor-associated differentiation antigens may have antitumor activities via CDC or ADCC as mediated by complement or immune effector cells, respectively, for example, natural killer and macrophages. These are not, however, the only mechanisms of Ab antitumor cytotoxicity. MAbs may have a direct antitumor activity without the participation of host components [48]. Abs do not cross the plasma membrane, unless it is permeabilized, but may be internalized by endocytosis. This may happen when the target is a receptor (e.g., receptors for transferrin, IL-2, EGF, TAPA-1 [the target of an antiproliferative antibody]) [49–52], but internalization of a mAb that recognized the Lewis Y carbohydrate epitope has also been reported [53,54]. This Ab (BR96) in the absence of complement or effector cells inhibited tumor cell DNA synthesis. However, it did not cause other alterations typical of apoptosis. In comparison, antimelanoma mAb A4 inhibited tumor cell growth in vitro in the absence of complement, recognized a surface receptor identified as protocadherin β13 (Pcdh β13), and was seemingly internalized, causing DNA degradation not only in murine but also in human melanoma cells. Morphological changes caused by mAb A4 such as cell blebbing, shrinkage, and loss of adherence suggested the induction of apoptosis. Furthermore, mAb A4 exerted a strong protective effect in vivo against B16F10-Nex2 melanoma cells implanted subcutaneously or injected intravenously.

As Ab targets, protocadherins represent a large subgroup within the cadherin family of cell-cell adhesion molecules. Many of the protocadherins in mammals are expressed in the central nervous system with a role in tissue morphogenesis, synaptic transmission, and specific connections [55]. It is not surprising then that Pcdh β13 is expressed on melanoma cells that originally derived from the neural crest. Pcdh proteins may determine diverse neuronal connections that require tremendous diversity for either positive or negative (detoxification) effects. A tandem array of Pcdh variable exons, encoding distinct polypeptides, participates in generating such diversity [56,57]. Invasive tumor cells seem to have plasticity similar to multipotent embryonic progenitors [58]. Recent evidence revealed that when melanoma cells were transplanted in the neural crest of chick embryo, the microenvironment had the potential to control and reverse the metastatic phenotype. During migration along the neural crest pathways, mouse melanoma cells underwent apoptosis, which was assessed by anti-caspase 3 and TUNEL staining [59]. We hypothesize that Pcdh β13 might be a regulatory surface antigen of melanoma cells that, as shown in the present work, responded to mAb A4 binding leading cells to apoptosis. The binding motif in the protocadherin shows a mimicry to the disaccharide melibiose as determined before, but the nature of the epitope, either linear or conformational, is still unknown [37].

Whereas the obtainment of mAb A4 recognizing a minor component in B16F10-Nex2 melanoma might be attributed to the immunization of mice with tumor cells grown in mouse serum-supplemented medium, thus avoiding xenogeneic contamination, mAb A4M seemed to respond as an autoimmune IgM reacting with nuclear histone H1. Antihistone Abs have been detected in the sera of patients with various autoimmune diseases and are predominantly directed to histone H1. The preferential reactivity of mAb A4M with a nuclear component was clearly shown in permeabilized tumor cells. Acid extraction of histones abolished the reactivity of the Ab. Moreover, mAb A4M did not react with DNA as tested in a Crithidia-DNA binding test (not shown). In contrast to mAb A4, A4M was not cytotoxic in vitro. If, however, the tumor cells had previously been permeabilized by a membrane-interacting peptide (e.g., the antimicrobial gomesin), mAb A4M showed additive cytotoxic activity [35].

MAb A4M also bound to intact melanoma cells in vitro with less affinity compared with mAb A4. By examining a biotinylated surface proteoma of B16F10-Nex2 melanoma cells kept for 24 hours in a fetal calf serum-free medium, evidence was obtained for the presence of histone H2B and histone H1.2 (unpublished data). It cannot be ruled out, however, that mAb A4M surface reactivity might also involve a conformational antigen mimicry. It has been reported that a mAb to Lewis Y/Lewis b carbohydrate epitopes also bound to bovine histone H1 and human histone H1.2 in a concentration-dependent manner [60]. Histone H2B was also recognized by the lung cancer-specific human mAb HB4C5 [61]. Furthermore, anti-DNA auto-Abs were found to crossreact with cell surface proteins from different cell types [62]. Then, it seems that autoimmune antinuclear Abs have a potential to cross-react with many other antigens of completely different structures.

Surprisingly, mAb A4M was protective in vivo against lung colonization by melanoma cells similarly to mAb A4. Antitumor activity was not mediated by complement, as it was the case with several polyclonal IgM Abs with antitumor activity [63,64]. There is evidence showing that some IgM molecules recognizing cell surface carbohydrates may have a tumor-suppressive activity by a macrophage-dependent mechanism [65]. Yet, another protective mechanism could involve an inflammatory response enhanced by IgM reactivity with necrotic tumor cells. IgM Abs that recognize internal antigens in necrotic metastatic melanoma cells can also be used as carriers of radioactive isotopes as shown with antimelanin Abs, thus becoming a valuable tool for radioimmunotherapy [66,67]. Therefore, both mAbs A4 and A4M of the present work represent promising tools for the immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma as shown in preclinical evaluation studies.

Polonelli et al. [36] obtained experimental evidence supporting the concept that peptides derived from internal sequences of immunoglobulins could display, with high frequency, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antitumor activities in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo. This was based on a series of previous contributions, recently reviewed by Magliani et al. [72], which showed that Ig fragments, tested as synthetic peptides derived from CDR domains and/or framework regions of immunoglobulins, had broad antibiotic properties similar to precursors and actual protective molecules of native immunity [68–73]. The bioactivity of these peptides was generally independent of Ab specificity, although it is well known that VH CDR3 (H3) may, in several instances, reproduce Ab-specific binding to the antigen and display the same biological activity [74–76]. The peptide (H3) with such properties is called a micro-Ab [47,77]. Presently, we extended these studies to mAbs A4 and A4M, with the perspective of additional antitumor molecules being unraveled.

Both mAbs A4 and A4M generated micro-Abs represented by peptide sequences of VH CDR3 tested as linear peptides or as extended H3 sequences made cyclic by adding Cys at the C-terminal and forming a Cys-Cys bond under oxidation conditions [46]. Linear and cyclic H3 peptides competed with mAbs A4 and A4M for binding to B16F10-Nex2 cells. The cyclic H3 form of mAb A4 showed greater affinity for melanoma cells than the linear H3 form. Both linear and cyclic mAb A4 H3 peptides inhibited growth of tumor cells, and the linear form caused DNA degradation, suggesting that the H3 peptide as well as the mAb A4 induced apoptosis in B16F10- Nex2 cells.

The only CDR frommAb A4 with antitumor activity was VHCDR3. In contrast, VH CDR3 from mAb A4M was not cytotoxic, thus acting as mAb A4Min vitro. Conversely, VL CDR 1 and VL CDR 2 from mAb A4M inhibited growth of B16F10-Nex2 cells in vitro and caused DNA degradation in the tumor cells. CDR L2, studied in greater detail, was shown to degrade DNA in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and its apoptotic effect was inhibited by the antiapoptotic Bcr-Abl, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL molecules transfected in HL-60 cells [78]. The antitumor effect of mAb A4M CDR L1 was significantly inhibited by replacing the last two hydrophobic residues at the C-terminal by alanine, thus suggesting a hydrophobic interaction with the tumor cell membrane. The shorter mAb A4M CDR L2 sequence lost its antitumor effect in vitro by alanine replacement of asparagine and lysine but mainly of threonine on the fourth position, suggesting a specific interaction with a surface receptor on the tumor cell. Remarkably, both mAb A4M CDRs L1 and L2 inhibited angiogenesis of HUVEC, which could also suggest that these peptides may be protective in vivo similarly as peptide C7 H2 and HuA L1 studied before [36].

In the present work, therefore, we describe two new specificities for antimelanoma mAbs showing that both mAbs A4 (IgG2a) and A4M (IgM) are protective in vivo against invasive B16F10-Nex2 cells in a model of lung metastasis. MAb A4 but not mAb A4M was cytotoxic in vitro and protective in the subcutaneous model of tumor development. An apoptotic micro-Ab was recognized in the VH CDR3 of mAb A4, and two VL CDRs (L1 and L2) of mAb A4M-induced apoptosis of melanoma cells and inhibited angiogenesis. They not only supported the concept of intrinsic bioactivity of Ig peptide sequences but also emerged as promising agents for antitumor therapy along with the tumor-suppressive mAbs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo Branch, and Alan N. Houghton from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, NY, for providing the human tumor cell lines used in this study. The authors also thank Antonio Furlanete for his support in chromatography, and the Biomolecule Analysis Core Facility at the Border Biomedical Research Center/Biology/University of Texas at El Paso for the access to the LC-MS instrument.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and Brazilian National Research Council (CNPq). L.R.T., E.G.R., and R.A.M. are recipients of fellowships from CNPq. E.S.N. was partially supported by the George A. Krutilek Memorial graduate scholarship from Graduate School, University of Texas at El Paso. I.C.A. was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health grant no. 5G12RR008124.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terheyden P, Tilgen W, Hauschild A. Recent aspects of medical care of malignant melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2008;6:868–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komenaka I, Hoerig H, Kaufman HL. Immunotherapy for melanoma. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:251–265. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vulink A, Radford KJ, Melief C, Hart DN. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;99:363–407. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(07)99006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547–564. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atkins MB. Immunotherapy and experimental approaches for metastatic melanoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:877–902. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar D, Su ZZ, Park ES, Vozhilla N, Dent P, Curiel DT, Fisher PB. A cancer terminator virus eradicates both primary and distant human melanomas. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:293–302. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanglmaier M, Reis S, Hallek M. Rituximab and alemtuzumab induce a nonclassic, caspase-independent apoptotic pathway in B-lymphoid cell lines and in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:634–645. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0917-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner GJ. Monoclonal antibody mechanisms of action in cancer. Immunol Res. 2007;39:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunpeng Z, Yugang W, Jugao C, Yan L, Beifen S, Yuanfang M. The construction and expression of a novel chimeric anti-DR5 antibody. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2009;28:101–105. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2008.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gridelli C, Maione P, Ferrara ML, Rossi A. Cetuximab and other anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2009;14:601–611. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakano K, Orita T, Nezu J, Yoshino T, Ohizumi I, Sugimoto M, Furugaki K, Kinoshita Y, Ishiguro T, Hamakubo T, et al. Anti-glypican 3 antibodies cause ADCC against human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ragupathi G, Liu NX, Musselli C, Powell S, Lloyd K, Livingston PO. Antibodies against tumor cell glycolipids and proteins, but not mucins, mediate complement-dependent cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2005;174:5706–5712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarron PA, Olwill SA, Marouf WM, Buick RJ, Walker B, Scott CJ. Antibody conjugates and therapeutic strategies. Mol Interv. 2005;5:368–380. doi: 10.1124/mi.5.6.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleckenstein G, Osmers R, Puchta J. Monoclonal antibodies in solid tumours: approaches to therapy with emphasis on gynaecological cancer. Med Oncol. 1998;15:212–221. doi: 10.1007/BF02787203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colman RW. Inhibition of angiogenesis by a monoclonal antibody to kininogen as well as by kininostatin which block proangiogenic high molecular weight kininogen. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1887–1894. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(02)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan X, Lin Y, Yang D, Shen Y, Yuan M, Zhang Z, Li P, Xia H, Li L, Luo D, et al. A novel anti-CD146 monoclonal antibody, AA98, inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Blood. 2003;102:184–191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song JS, Sainz IM, Cosenza SC, Isordia-Salas I, Bior A, Bradford HN, Guo YL, Pixley RA, Reddy EP, Colman RW. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis in vivo by a monoclonal antibody targeted to domain 5 of high molecular weight kininogen. Blood. 2004;104:2065–2072. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalle S, Thieblemont C, Thomas L, Dumontet C. Monoclonal antibodies in clinical oncology. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.2174/187152008784533071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma WW, Adjei AA. Novel agents on the horizon for cancer therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:111–137. doi: 10.3322/caac.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pukel CS, Lloyd KO, Travassos LR, Dippold WG, Oettgen HF, Old LJ. GD3, a prominent ganglioside of human melanoma. Detection and characterisation by mouse monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1133–1147. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houghton AN, Mintzer D, Cordon-Cardo C, Welt S, Fliegel B, Vadhan S, Carswell E, Melamed MR, Oettgen HF, Old LJ. Mouse monoclonal IgG3 antibody detecting GD3 ganglioside: a phase I trial in patients with malignant melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soiffer RJ, Chapman PB, Murray C, Williams L, Unger P, Collins H, Houghton AN, Ritz J. Administration of R24 monoclonal antibody and low-dose interleukin 2 for malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber J. Overcoming immunologic tolerance to melanoma: targeting CTLA-4 with ipilimumab (MDX-010) Oncologist. 2008;13(suppl 4):16–25. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S4-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigler M, Villares GJ, Lev DC, Melnikova VO, Bar-Eli M. Tumor immunotherapy in melanoma: strategies for overcoming mechanisms of resistance and escape. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:307–311. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melnikova VO, Bar-Eli M. Bioimmunotherapy for melanoma using fully human antibodies targeting MCAM/MUC18 and IL-8. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19:395–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills L, Tellez C, Huang S, Baker C, McCarty M, Green L, Gudas JM, Feng X, Bar-Eli M. Fully human antibodies to MCAM/MUC18 inhibit tumor growth and metastasis of human melanoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5106–5114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shadidi M, Sioud M. Selective targeting of cancer cells using synthetic peptides. Drug Resist Updat. 2003;6:363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apostolopoulos V. Peptide-based vaccines for cancer: are we choosing the right peptides? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:259–260. doi: 10.1586/14760584.8.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brinkman JA, Fausch SC, Weber JS, Kast WM. Peptide-based vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:181–198. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miao Y, Quinn TP. Peptide-targeted radionuclide therapy for melanoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67:213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao Y, Hylarides M, Fisher DR, Shelton T, Moore H, Wester DW, Fritzberg AR, Winkelmann CT, Hoffman T, Quinn TP. Melanoma therapy via peptide-targeted {alpha}-radiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5616–5621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purcell AW, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. More than one reason to rethink the use of peptides in vaccine design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrd2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daffre S, Bulet P, Spisni A, Ehret-Sabatier L, Rodrigues EG, Travassos LR. Bioactive natural peptides. In: A-u-Rahman, editor. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. UK: Elsevier Oxford; 2008. pp. 597–691. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodrigues EG, Dobroff AS, Cavarsan CF, Paschoalin T, Nimrichter L, Mortara RA, Santos EL, Fazio MA, Miranda A, Daffre S, et al. Effective topical treatment of subcutaneous murine B16F10-Nex2 melanoma by the antimicrobial peptide gomesin. Neoplasia. 2008;10:61–68. doi: 10.1593/neo.07885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polonelli L, Ponton J, Elguezabal N, Moragues MD, Casoli C, Pilotti E, Ronzi P, Dobroff AS, Rodrigues EG, Juliano MA, et al. Antibody complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) can display differential antimicrobial, antiviral and antitumor activities. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2371–e2371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobroff AS, Rodrigues EG, Moraes JZ, Travassos LR. Protective, anti-tumor monoclonal antibody recognizes a conformational epitope similar to melibiose at the surface of invasive murine melanoma cells. Hybrid Hybridomics. 2002;21:321–331. doi: 10.1089/153685902761022661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouvet JP, Pires R, Pillot J. A modified gel filtration technique producing an unusual exclusion volume of IgM: a simple way of preparing monoclonal IgM. J Immunol Methods. 1984;66:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paschoalin T, Carmona AK, Oliveira V, Juliano L, Travassos LR. Characterization of thimet- and neurolysin-like activities in Escherichia coli M 3 A peptidases and description of a specific substrate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;441:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone KL, Williams KR. Enzymatic digestion of proteins in solution and in SDS polyacrylamide gels. In: Walker JM, editor. The Protein Protocols Handbook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1996. pp. 415–425. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jurado JD, Rael ED, Lieb CS, Nakayasu E, Hayes WK, Bush SP, Ross JA. Complement inactivating proteins and intraspecies venom variation in Crotalus oreganus helleri. Toxicon. 2007;49:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci MC, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paschoalin T, Carmona AK, Rodrigues EG, Oliveira V, Monteiro HP, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Travassos LR. Characterization of thimet oligopeptidase and neurolysin activities in B16F10-Nex2 tumor cells and their involvement in angiogenesis and tumor growth. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:44–44. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanhalst K, Kools P, Vanden Eynde E, van Roy F. The human and murine protocadherin-beta one-exon gene families show high evolutionary conservation, despite the difference in gene number. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:120–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morea V, Tramontano A, Rustici M, Chothia C, Lesk AM. Conformations of the third hypervariable region in the VH domain of immunoglobulins. J Mol Biol. 1998;275:269–294. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levi M, Sallberg M, Ruden U, Herlyn D, Maruyama H, Wigzell H, Marks J, Wahren B. A complementarity-determining region synthetic peptide acts as a miniantibody and neutralizes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4374–4378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drebin JA, Link VC, Greene MI. Monoclonal antibodies specific for the neu oncogene product directly mediate anti-tumor effects in vivo. Oncogene. 1988;2:387–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trowbridge IS, Domingo DL. Anti-transferrin receptor monoclonal antibody and toxin-antibody conjugates affect growth of human tumour cells. Nature. 1981;294:171–173. doi: 10.1038/294171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyawaki T, Yachie A, Uwadana N, Ohzeki S, Nagaoki T, Taniguchi N. Functional significance of Tac antigen expressed on activated human T lymphocytes: Tac antigen interacts with T cell growth factor in cellular proliferation. J Immunol. 1982;129:2474–2478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masui H, Kawamoto T, Sato JD, Wolf B, Sato G, Mendelsohn J. Growth inhibition of human tumor cells in athymic mice by anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1984;44:1002–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oren R, Takahashi S, Doss C, Levy R, Levy S. TAPA-1, the target of an antiproliferative antibody, defines a new family of transmembrane proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4007–4015. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.8.4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hellstrom I, Garrigues HJ, Garrigues U, Hellstrom KE. Highly tumorreactive, internalizing, mouse monoclonal antibodies to Le(y)-related cell surface antigens. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2183–2190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garrigues J, Garrigues U, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE. Ley specific antibody with potent anti-tumor activity is internalized and degraded in lysosomes. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:607–622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frank M, Kemler R. Protocadherins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:557–562. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu Q, Zhang T, Cheng JF, Kim Y, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Noonan JP, Zhang MQ, Myers RM, et al. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of mouse and human protocadherin gene clusters. Genome Res. 2001;11:389–404. doi: 10.1101/gr.167301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang T, Haws P, Wu Q. Multiple variable first exons: a mechanism for cell- and tissue-specific gene regulation. Genome Res. 2004;14:79–89. doi: 10.1101/gr.1225204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Teddy JM, Postovit LM, Seftor EA, Seftor RE, Hendrix MJ, Kulesa PM. Reprogramming multipotent tumor cells with the embryonic neural crest microenvironment. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2657–2666. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oppitz M, Busch C, Schriek G, Metzger M, Just L, Drews U. Nonmalignant migration of B16 mouse melanoma cells in the neural crest and invasive growth in the eye cup of the chick embryo. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:17–30. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3280114f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christensen PA, Danielczyk A, Ravn P, Stahn R, Karsten U, Goletz S. A monoclonal antibody to Lewis Y/Lewis b revealing mimicry of the histone H1 to carbohydrate structures. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:362–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kato M, Mochizuki K, Kuroda K, Sato S, Murakami H, Yasumoto K, Nomoto K, Hashizume S. Histone H2B as an antigen recognized by lung cancer-specific human monoclonal antibody HB4C5. Hum Antibodies Hybridomas. 1991;2:94–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Raz E, Ben-Bassat H, Davidi T, Shlomai Z, Eilat D. Cross-reactions of anti-DNA autoantibodies with cell surface proteins. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:383–390. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greenberg AH, Chow DA, Wolosin LB. Natural antibodies: origin, genetics, specificity and role in host resistance to tumours. Clin Immunol Allergy. 1983;3:389–420. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Subiza JL, Coll J, Alvarez R, Valdivieso M, de la Concha EG. IgM response and resistance to ascites tumor growth. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1987;25:87–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00199946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gil J, Alvarez R, Vinuela JE, Ruiz de Morales JG, Bustos A, Dela Concha EG, Subiza JL. Inhibition of in vivo tumor growth by a monoclonal IgM antibody recognizing tumor cell surface carbohydrates. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7301–7306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dadachova E, Revskaya E, Sesay MA, Damania H, Boucher R, Sellers RS, Howell RC, Burns L, Thornton GB, Natarajan A, et al. Pre-clinical evaluation and efficacy studies of a melanin-binding IgM antibody labeled with 188Re against experimental human metastatic melanoma in nude mice. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1116–1127. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Revskaya E, Jongco AM, Sellers RS, Howell RC, Koba W, Guimaraes AJ, Nosanchuk JD, Casadevall A, Dadachova E. Radioimmunotherapy of experimental human metastatic melanoma with melanin-binding antibodies and in combination with dacarbazine. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2373–2379. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Magliani W, Conti S, Maffei DL, Ravanetti L, Polonelli L. Antiidiotype-derived killer peptides as new potential tools to combat HIV-1 and AIDS-related opportunistic pathogens. Anti Infective Agents Med Chem. 2007;6:263–272. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Magliani W, Conti S, Salati A, Arseni S, Ravanetti L, Frazzi R, Polonelli L. Engineered killer mimotopes: new synthetic peptides for antimicrobial therapy. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1793–1800. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Magliani W, Conti S, Travassos LR, Polonelli L. From yeast killer toxins to antibiobodies and beyond. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;288:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Polonelli L, Magliani W, Conti S, Bracci L, Lozzi L, Neri P, Adriani D, De Bernardis F, Cassone A. Therapeutic activity of an engineered synthetic killer antiidiotypic antibody fragment against experimental mucosal and systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6205–6212. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6205-6212.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Magliani W, Conti S, Cunha RL, Travassos LR, Polonelli L. Antibodies as crypts of antiinfective and antitumor peptides. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:2305–2323. doi: 10.2174/092986709788453104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Litman GW, Cannon JP, Dishaw LJ. Reconstructing immune phylogeny: new perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:866–879. doi: 10.1038/nri1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bourgeois C, Bour JB, Aho LS, Pothier P. Prophylactic administration of a complementarity-determining region derived from a neutralizing monoclonal antibody is effective against respiratory syncytial virus infection in BALB/c mice. J Virol. 1998;72:807–810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.807-810.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu JL, Davis MM. Diversity in the CDR3 region of V(H) is sufficient for most antibody specificities. Immunity. 2000;13:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dorfman T, Moore MJ, Guth AC, Choe H, Farzan M. A tyrosine-sulfated peptide derived from the heavy-chain CDR3 region of an HIV-1-neutralizing antibody binds gp120 and inhibits HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28529–28535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heap CJ, Wang Y, Pinheiro TJ, Reading SA, Jennings KR, Dimmock NJ. Analysis of a 17-amino acid residue, virus-neutralizing microantibody. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1791–1800. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brumatti G, Weinlich R, Chehab CF, Yon M, Amarante-Mendes GP. Comparison of the anti-apoptotic effects of Bcr-Abl, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL following diverse apoptogenic stimuli. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]