Abstract

Noninvasive functional imaging of tumors can provide valuable early-response biomarkers, in particular, for targeted chemotherapy. Using various experimental tumor models, we have investigated the ability of positron emission tomography (PET) measurements of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-glucose (FDG) and 3′-deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine (FLT) to detect response to the allosteric mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus. Tumor models were declared sensitive (murine melanoma B16/BL6 and human lung H596) or relatively insensitive (human colon HCT116 and cervical KB31), according to the IC50 values (concentration inhibiting cell growth by 50%) for inhibition of proliferation in vitro (<10 nM and >1 µM, respectively). Everolimus strongly inhibited growth of the sensitive models in vivo but also significantly inhibited growth of the insensitive models, an effect attributable to its known anti-angiogenic/vascular properties. However, although tumor FDG and FLT uptake was significantly reduced in the sensitive models, it was not affected in the insensitive models, suggesting that endothelial-directed effects could not be detected by these PET tracers. Consistent with this hypothesis, in a well-vascularized orthotopic rat mammary tumor model, other antiangiogenic agents also failed to affect FDG uptake, despite inhibiting tumor growth. In contrast, the cytotoxic patupilone, a microtubule stabilizer, blocked tumor growth, and markedly reduced FDG uptake. These results suggest that FDG/FLT-PET may not be a suitable method for early markers of response to antiangiogenic agents and mTOR inhibitors in which anti-angiogenic/vascular effects predominate because the method could provide false-negative responses. These conclusions warrant clinical testing.

Introduction

Everolimus (Afinitor; Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland) is an allosteric mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor recently approved for the treatment of second-line renal cell carcinoma. The protein mTOR is a multifunctional signal-transducing enzyme that functions downstream of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway and influences the translation of many proteins known to be important in cancer [1]. Inhibition of mTOR by everolimus and other derivatives of rapamycin (rapalogs) results in tumor growth inhibition rather than regression in preclinical models [2,3] and similar observations are emerging in the clinic. For example, in the phase 3 registration trial in renal cell carcinoma, the objective partial response rate was only 2%, although there was a highly significant extension of the progression-free survival compared with placebo [4], which translated into increased survival despite crossover in the trial [5]. This trial clearly demonstrates that merely quantifying tumor size can be an inadequate measurement of the activity of a targeted agent such as everolimus. Thus, the development of more targeted agents in oncology mandates the application of biomarkers that can help provide a reliable marker of response, as well as identifying an optimal biologic dose (OBD), mechanism of action (MoA), and the population to be treated. A number of different approaches for these tasks are available, which include sampling of the plasma, tumor biopsies, or functional imaging. The latter is particularly attractive because, in principle, it allows repeated noninvasive imaging of the whole target tissue rather than sampling of a heterogeneous section. Several imaging methods are available, each of which provides different advantages, and one that is becoming increasingly used is positron emission tomography (PET).

Various PET methods may be used in oncology using radiotracers to assess different aspects of tumor biology such as [15O]H2O for tumor blood flow (TBF), 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-glucose (FDG) for glycolysis and thus cell viability, 3′-deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine (FLT) for S-phase and thus proliferation, and [18F]fluoromisonidazole (FMISO) for hypoxia [6]. One of the consequences of mTOR inhibition is a reduction in levels of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1)[7], which causes decreased levels of HIF-1 transcriptional targets including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), PDGF, glycolytic enzymes, and glucose transporters. Other consequences of mTOR inhibition include reduced levels of the cyclins that drive the cell cycle, which results in a G1/S block. In principle, therefore, an mTOR inhibitor should cause reduced FDG and FLT uptake by tumors as well as reduced angiogenesis. Indeed, in nonclinical models using everolimus, evidence of antiangiogenic effects have been recorded [2,7] along with a dose-dependent reduction of FDG uptake [8]. Rapamycin has also been shown to reduce FDG and FLT uptake both in vitro and in vivo in sensitive glioma cell lines but not in a strongly resistant glioma model [9]. The most sensitive glioma cell line, U87, showed reduced hexokinase activity and reduced thymidine kinase expression after 24 hours of treatment with rapamycin [9], which are the enzymes most likely governing uptake of FDG and FLT, respectively [6]. Collectively, these data support the notion of imaging tumor glucose and thymidine utilization for monitoring response to rapalogs in the clinic. However, although some decreases in FDG uptake (6/8) were detected in a non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) study for everolimus [10], another report from phase 1/2 studies showed no correlation between FDG changes and response to rapamycin in solid tumors for 34 patients [11].

In this nonclinical study, we have investigated the effects of everolimus on FDG and FLT uptake in human tumor xenografts derived from cell lines characterized as sensitive or insensitive in vitro. We show that in vivo, everolimus can inhibit growth of both types of tumor, which, in these insensitive models, probably reflects the antiangiogenic activity of the drug, but only the xenografts derived from sensitive cells showed significant changes in FDG and FLT uptake. Consistent with these observations, other antiangiogenic compounds also failed to affect FDG uptake, whereas a classic cytotoxic interfering with microtubule function caused a marked decrease in FDG uptake. These data suggest that FDG/FLT-PET may not always be a suitable marker of tumor response because it could lead to a number of false-negatives for anticancer agents whose primary MoA is antiangiogenic. Thus, although positive PET responses are always useful, negative PET responses would, in these cases, preclude PET being used to obtain an OBD.

Materials and Methods

All animal experiments were carried out strictly according to regulations of the State Veterinary Authorities of the Cantons of Basel and Zurich. Female Brown-Norway rats and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River (France) and female Harlan Hsd:Npa nu/nu (nude) athymic mice were obtained from the Novartis breeding stock (Basel, Switzerland). Rats weighed between 135 and 180 g, whereas mice weighed between 20 and 30 g before experiments.

Experimental Tumor Models

Five different tumor models were used, all of which have been previously described in detail [12]. Briefly, two orthotopic syngeneic tumor models were used: (a) murine B16/BL6 melanoma cells in C57BL/6 mice, where cells injected intradermally in the ear metastasize rapidly to the lymph nodes of the neck (LN-mets), and (b) rat mammary BN472 tumors transplanted from donor rats by inoculation of fresh tumor material in the mammary fat pad. The human tumor cell lines HCT116 colon, KB31 cervical, and H596 lung were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) in the flanks of athymic nude mice. All models were used ca. 3 weeks after transplantation or inoculation when tumors were ca. 100 to 200 mm3 in mice and 200 to 500 mm3 in rats (see individual studies).

Tumors were measured by noninvasive PET (see below), or the size (volume) of all tumors (TVol) was determined using calipers to measure three orthogonal dimensions and applying the formula: l x h x w x π / 6. TVol and animal body weight (BW) measurements were made thrice per week, just before treatment (baseline), and at the end point.

Compounds/Drugs and Their Application

All compounds used in this study were obtained from the Novartis Chemistry Research or Pharmaceutical Development. The compounds and their respective vehicles were prepared each day just before administration to animals, and the administration volumes were individually adjusted based on the animal's BW.

Everolimus (RAD001), an mTOR inhibitor, was obtained as a microemulsion and was freshly diluted in a vehicle of 5% glucose and administered by oral gavage (p.o.) to mice daily in a volume 10 ml/kg at 10 mg/kg.

Patupilone (epothilone B, EPO906), a microtubule stabilizer, was dissolved in polyethylene glycol-300 (PEG-300) and then diluted with physiological saline (0.9% wt./vol. NaCl) to obtain a mixture of 30% (vol./vol.) PEG-300 and 70% (vol./vol.) 0.9% saline. Treatment with vehicle (PEG-300/saline) or patupilone was once weekly using an intravenous (i.v.) bolus in the tail vein (2 ml/kg at 0.75 mg/kg) in rats.

PTK/ZK (vatalanib), a pan-VEGF receptor (VEGF-R) inhibitor, was dissolved in 100% vol./vol. PEG-300 and then diluted 1:1 in 0.9% saline. Rats received PTK/ZK dosed daily at 100 or 200 mg/kg p.o. (5 ml/kg).

NVP-AAL881, a dual RAF and KDR (VEGF-R2) inhibitor, was dissolved in 1 ml of 100% ethanol at a maximum concentration of 25 mg/ml, and then 1 ml of 100% vol./vol. Cremophor EL (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany) was added and vortexed. Finally, 8 ml of a solution of 5% (vol./vol.) glucose in distilled water was added and mixed to give 10 ml at 2.5 mg/ml. NVP-AAL881 was dosed at 15 mg/kg p.o. twice daily in rats at 5 ml/kg.

Positron Emission Tomography

FDG was obtained from the commercial production of the University Hospital Zurich (UniversitätsSpital Zürich) with a specific activity of ca. 1000 GBq/µmol. FLT and FMISO were produced in-house at the Department of Radiopharmaceutical Science of the Federal Institute of Technology of Zurich (Eidgenoessische Technische Hochschule) as previously described [13,14]. For both tracers, specific radioactivities were always higher than 100 GBq/µmol.

PET experiments were performed as previously reported [12]; tumor is easily distinguishable from background, and the method is highly reproducible. Briefly, each tracer (5–45 MBq; 150 µl) was injected i.v. in nonfasted, restrained animals allowing distribution and accumulation of the radiotracer in the nonanesthetized animal, that is, under physiological conditions. Injected doses were precisely quantified by measuring radioactivity in the syringes before and after radiotracer application. After tracer injection, at 20 minutes for FDG and FLT or at 80 minutes for FMISO, the animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (Abbott, Cham, Switzerland) in an air/oxygen mixture and fixed on the bed of the scanner. PET experiments were performed using the dedicated 16-module quad HIDAC tomograph with a submillimeter resolution (Oxford Positron Systems, Weston-on-the-Green, UK) and a field of view of 280 mm axially and 170 mm in diameter. PET data acquisition was initiated 30 minutes (FDG and FLT) or 90 minutes (FMISO) after radiotracer injection. A warm air stream was used to ensure thermostasis at 37°C body temperature, measured by a rectal probe. Depth of anesthesia was controlled by monitoring respiratory frequency with a dedicated thorax belt.

Raw data files were acquired in list mode and reconstructed in single time frame using the OPL-EM algorithm [12] and a bin size of 0.5 mm. Reconstruction did not include scatter, random, and attenuation correction. A simultaneous Na-22 point source measurement was used as an internal standard to correct the reconstructed data sets for possible variations in scanner sensitivity. Reconstructed three-dimensional PET data were evaluated by a region of interest (ROI) analysis using the dedicated biomedical image quantification software PMOD (Pmod Technologies Ltd, Adliswil, Switzerland). ROIs were drawn manually in all coronal slices comprising the tumor, thus providing volume and the average activity concentration of the entire tumor. For FDG and FLT studies, the average activity concentration in the tumor was normalized to the injected dose per BW and expressed as an average standardized uptake value (SUV). For FMISO experiments, ROIs were also drawn on 5 to 10 subsequent coronal planes containing muscle tissue at a forelimb. The quantification of FMISO uptake was based on the tumor-to-muscle retention ratio (TMRR) using muscle tissue as a reference region, where a TMRR ≥ 1.4 defines the presence of hypoxia [15].

Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Animals were anesthetized using constant inhalation of 1.5% isoflurane (Abbott) in a 1:1 mixture of O2/N2 while the animal was lying on an electrically warmed pad and were cannulated through one lateral tail vein as previously described [16]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) experiments were performed on a Bruker DBX 47/30 or Avance 2 spectrometer (Bruker Medical, Fällanden, Switzerland) at 4.7 T equipped with a self-shielded 12-cm bore gradient system.

For determination of the relative tumor blood volume (rTBV) and blood flow index (BFI), the iron oxide particle intravascular contrast agent Endorem (Guerbet, Roissy, France) was injected (6 mmol/kg of iron). The Endorem uptake curve was fitted with a sigmoid curve (BioMap based on IDL; Research Systems, Inc, Boulder, CO) to provide a value for the rTBV (plateau) and the BFI, which was the rTBV divided by the steepest part of the slope. Values shown in the Results section are in arbitrary units, and the principles behind measurement of these parameters have been fully described [16].

For determination of macrophage levels, the contrast agent Sinerem (Guerbet) was used, which is composed of ultra small particles of iron oxide (USPIO). The ultra small particles of iron oxide can be internalized by cells of the mononuclear phagocytotic system (including macrophages) by absorptive endocytosis and enables tracking of these cells [17]. For each measuring time point, reference images were acquired before infusion of 80 µl of Sinerem/100 mg BW and another series of images 24 hours after infusion of Sinerem. The T2-weighted MRI signal intensities from the tumor were standardized by comparing to the signal of a coimaged phantom containing 1 mM MnCl2 solution. Sinerem causes a decrease in signal intensity, and the extent of this attenuation (percentage) is proportional to the macrophage level.

Experimental Design

When tumors reached the desired size for the study, the tumor-bearing animals were allocated to different treatment groups, based on tumor volume, to balance the groups, and various measurements were made before treatment (baseline), that is, day 0, and at various time points after treatment. The posttreatment time points were selected as early (day 2 or 3) and/or late (day 6 or 7 or exceptionally day 14) with the late time point normally being the end point. At the end of all experiments, animals were killed by CO2 inhalation or decapitation. In some cases, after the final measurement at the end point, the tumors were ablated and studied by histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Ex Vivo Studies

Histology and IHC were done as previously described [12,18] to determine the number of cells positive for cleaved caspase 3 (apoptosis marker) or the proliferation markers Ki67 and PCNA. In addition, cells were scored for the glucose transporter, Glut-1 (RB-9052; Neomarkers, Fremont, CA).

Macrophages were visualized by immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibody ED1 (Serotec, Düsseldorf, Germany) directed against rat macrophage lysosomal membrane. Briefly, microwave-assisted antigen retrieval was carried out for 20 minutes in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. After washing in buffered saline, endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0.5% H2O2 in methanol for 20 minutes at room temperature (RT). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 10% normal horse serum for 20 minutes at RT, and the sections were incubated with the primary antibody ED1 diluted 1:100 in 1% normal horse serum, overnight at RT. Negative controls were incubated with mouse isotype control (Zymed, San Francisco, CA). After washing in buffered saline, sections were incubated with biotinylated horse anti-mouse immunoglobulin G, preabsorbed with rat serum (Vector, Burlingame, CA) followed by avidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase complex (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Peroxidase activity was visualized by incubation in a solution of 3.3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Medite, Nunningen, Switzerland). Sections were counterstained with neutral red and mounted with Pertex (Medite, Nunningen, Switzerland).

For the detection of “free” iron (not phagocytized), macrophages were first demonstrated by immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibody ED1, then the Perl Prussian blue reaction was applied to the slides.

Data Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM except where stated, and all available data are shown. The effect of a compound on a particular parameter, for example, FDG tumor uptake is summarized as the T/C, that is, the mean change compared with baseline for drug-treated animals divided by the mean change in treatment for vehicle-treated animals compared with baseline to provide a T/CFDG as previously described [12]. For tumor volume (TVol), BW, and all ex vivo analyses, differences between groups were analyzed using a t test (for two groups) or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett or Tukey tests post hoc. For the in vivo biomarker analyses that involved longitudinal analyses in the same animals, differences were analyzed by (a) two-way repeated-measures ANOVA and (b) t test or one-way ANOVA as appropriate for each time point; the latter method is therefore associated with the respective T/C. If necessary, data were normalized by a log10 transformation before statistical analyses. Quantification of the relationship between two parameters was analyzed by the Spearman correlation to provide the correlation coefficient (r) and the significance (P). For all statistical tests, the level of significance was set at P < .05 (two-tailed) where *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 versus vehicle.

Results

Effects of Everolimus on FDG uptake by Sensitive Tumors

We have previously characterized the activity of everolimus in cell culture using 48 different tumor cell lines [3]. On the basis of the concentration inhibiting cell growth by 50% (IC50) for cell proliferation during 3 days of incubation, cells could be divided into sensitive (IC50 values of 0.2–65 nM) and insensitive (IC50 values of 150–4125 nM). One of the cell lines very sensitive to everolimus in vitro (IC50 = 0.7 nM) were murine B16/BL6 melanoma cells, and when grown in syngeneic mice, everolimus dose dependently (0.1–10 mg/kg daily) inhibited growth [2]. For the experiments described in this report, everolimus was dosed daily at 10 mg/kg (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anticancer Activity of Everolimus In Vivo.

| Tumor Model | IC50 (nM) | T/CTVol at the End Point | 1 Week 2–3 Week Median | |

| Murine B16/BL6 LN-met | 0.7 | 0.16, 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.27 |

| Human H596 | 5 | 0.37 | 0.12, 0.14, 0.35 | 0.25 |

| Human KB31 | 1778 | 0.43 | 0.32, 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Human HCT116 | 4125 | 0.59 | 0.33, 0.46, 0.50 | 0.48 |

Results show the efficacy of everolimus (T/CTVol) in several different experiments (separated by a comma) against the different tumor models described in this report, along with the median of the three to four experiments. Everolimus was always dosed daily at 10 mg/kg p.o. except in two of the KB31 experiments where 2.5 mg/kg was used (dose-response analyses showed that 2.5 and 10 mg/kg produced equivalent efficacy in this model; see O'Reilly et al. [45]).

Total uptake of FDG by orthotopic B16/BL6 melanomas in vivo was strong (mean SUV: 1.75 ± 0.1, n = 10) and relatively homogeneous in both the primary tumors in the ear and in the lymph node metastases in the neck (Figure 1A). Daily dosing with everolimus (10 mg/kg) after 2 days caused a marked decrease of FDG uptake in 9 of 10 metastases, with an overall highly significant (P < .001) decrease in the mean SUV of 42% from 1.8 ± 0.1 to 1.1 ± 0.1 (Figure 1B). Very similar effects were detected in the primary tumors. In separate experiments, dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the LN-mets showed no effect of everolimus on either rTBV or BFI after 2 days of treatment (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Everolimus decreases FDG uptake by murine melanoma B16/BL6 metastases. Murine B16/BL6 cells were injected intradermally in the ears of C57BL/6 mice, and after 2 weeks, the lymph node metastases were studied by FDG-PET as described in the Materials and Methods section, immediately before and 2 days after treatment with everolimus (10 mg/kg p.o.). (A) Representative experiment showing horizontal head/thorax images of mice with lymph node (red arrow) and primary ear tumors (blue arrow) before and after treatment with everolimus. (B) Individual SUVs for tumors (n = 10 per treatment group) and the mean ± SEM fractional effect of treatment, where ***P < .001. (C) Mean ± SEM fractional changes for the effect of vehicle or everolimus on rTBVol, n = 19 per group, and BFI, n = 14 per group.

The human NSCLC cell line, H596, is also sensitive to everolimus causing a marked reduction in S-phase after 48 hours (T/C = 0.72) and inhibiting proliferation in vitro with an IC50 of 5 nM. When grown as a s.c. xenograft in athymic nude mice, daily dosing at 10 mg/kg strongly inhibited growth; T/CTVol after 3 weeks was 0.14 (Figure 2A and Table 1). As previously reported [12], uptake of FDG by human tumor xenografts is rather low, and indeed, H596 tumors had a mean SUV of just 0.23 ± 0.02 (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, two daily doses caused a significant, albeit small decrease of ca. 20% in the SUV to 0.17 ± 0.01 (Figure 2, B and C). Analysis ex vivo of these tumors on day 2 showed no significant effects of everolimus on necrosis or staining for caspase 3+ and Ki67+ cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Everolimus decreases FDG uptake by human H596 lung tumor xenografts. Human tumors were created by s.c. implantation of viable H596 tumor tissue in Harlan athymic mice. (A) For efficacy, mice were treated with vehicle or with everolimus (10 mg/kg p.o.) for 21 days. Results show mean ± SEM. (B and C) A separate cohort of tumor-bearing mice was studied by FDG-PET as described in the Materials and Methods section, immediately before and 2 days after treatment with everolimus. Results show the individual SUVs for tumors (n = 10 per treatment group) and the mean ± SEM fractional effect of treatment, where *P < .05, **P <.01. (D) Histology and IHC of ablated tumors on day 2 after completion of the second PET scan.

Effects of Everolimus on FDG Uptake by Insensitive Tumors

Human colon HCT116 cells are insensitive to everolimus in vitro (IC50 = 4 µM), yet daily dosing by the drug (10 mg/kg) could significantly inhibit tumor growth after at least 1 week of treatment (Figure 3, A and B, and Table 1). It is likely that this activity in vivo reflects the anti-angiogenic/vascular activity of everolimus, which is a potent inhibitor of cultured human endothelial cells (IC50 = 0.1 nM) and other stromal cells and decreases tumor microvessel density [2]. Despite this significant growth inhibition, no changes in FDG uptake were detectable after 2 or 7 days of treatment (Figure 3C), and in a prolonged experiment, no decrease compared with vehicle was apparent after 2 weeks of treatment (Figure 3D). Similar data were obtained using the everolimus-insensitive KB31 model (IC50 = 1.8 µM), in which significant growth inhibition in vivo could be observed (Figure 3E and Table 1), yet there were no significant changes in FDG uptake relative to vehicle after 2 or 7 days of treatment (Figure 3F). In both of these xenograft models, the basal mean SUV was low at ca. 0.2 and similar to the H596 model.

Figure 3.

Everolimus inhibits growth of insensitive human tumors but does not affect FDG uptake. Human HCT116 (colon) and KB31 (cervical) were created by s.c. injection of cells in Harlan athymic mice. In all cases, mice were treated daily p.o. with vehicle or everolimus (10 mg/kg). (A and B) Efficacy in HCT116 tumors for 1 week (A) or 2 weeks (B) showing the mean ± SEM with the associated T/CTVol at the end point. (C and D) FDG-PET in HCT116 tumors in the respective experiment showing the mean fractional change for each treatment compared with day 0 (C) or the individual tumor SUV at two different time points (D). (E and F) Efficacy in KB31 tumors with the fractional change in FDG-PET compared with day 0 for each treatment, where *P < .05, ***P < .001.

Effects of Everolimus on FLT Tumor Uptake

As previously reported [12], uptake of FLT in human tumor xenografts was less rim-limited than for FDG (Figure 4A) and showed a higher mean basal SUV. Daily dosing with everolimus after 2 days caused a significant decrease of 20% in FLT uptake in the sensitive H596 tumors (Figure 4B), and again in this model, ex vivo analysis showed no significant effects on necrosis or staining for caspase 3+ and Ki67+ cells (Figure 4C). At this end point of 2 days, there was a weak significant correlation between Ki67+ cells and FLT by tumor cells (r = 0.6, P = .04). Repeat experiments showed similar significant effects on FLT uptake after 2 days, and another experiment extended to 7 days showed no evidence of a greater effect with time (Figure W1). This experiment showed that, also on day 7, there were no significant effects on necrosis or staining for caspase 3+ or Ki67+ cells, and at the later end point of 7 days, there was no correlation between FLT and Ki67 (r = 0.13, P = .69). H596 tumors showed strong staining for PCNA and Glut-1 (>90%), but there was no evidence either that everolimus affected these parameters after 7 days of treatment (Figure W1).

Figure 4.

Everolimus decreases FLT uptake by human H596 lung tumor xenografts. Human tumors were created by s.c. implantation of viable H596 tumor tissue in Harlan athymic mice. Tumors were studied by FLT-PET as described in the Materials and Methods section, immediately before and 2 days after treatment with everolimus (10 mg/kg p.o.). (A) Representative experiment showing horizontal whole-body images of mice with tumors (blue arrow) before and after treatment with everolimus; red arrow indicates the bladder. (B) Individual SUVs for tumors (n = 6 per treatment group), and the mean ± SEM fractional effect of treatment, where **P < .01. (C) Histology and IHC of ablated tumors on day 2 after completion of the second PET scan.

In the insensitive HCT116 model, everolimus was without significant effect on FLT uptake either at day 3 or day 10 after initiation of daily treatment (Figure 5, A and B). Again, there were no significant effects on necrosis or percent Ki67+, whereas caspase 3+ staining showed a trend to increase (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Everolimus does not affect FLT uptake by human HCT116 colon tumor xenografts. Human HCT116 tumors were created by s.c. injection of cells in Harlan athymic mice. (A and B) Tumors were studied by FLT-PET as described in the Materials and Methods section, immediately before (day 0) and on days 3 and 10 after treatment with vehicle or everolimus (10 mg/kg p.o.). Results show (n = 6 per treatment group) the individual SUVs for tumors (A) and the mean ± SEM fractional effect of treatment (B). (C) Histology and IHC of ablated tumors on day 10 after completion of the second PET scan.

Thus, in sensitive models, everolimus rapidly decreased both FDG and FLT uptake but had no effect on these parameters in insensitive models despite significant inhibition of tumor growth. In both types of model, a well-known marker of mTOR inhibition, pS6, was strongly downregulated [2], but apparently in the insensitive tumors, this was not transmitted into downstream effects that affect FDG or FLT uptake. In contrast, everolimus had no effect on the IHC markers of Ki67 and apoptosis in H596 or HCT116 tumors. Perhaps this is less surprising given the MoA of everolimus, which is to slow or to block the G1/S transition rather than to cause cell death [19,20]. Thus, because Ki67 measures the total number of cycling cells rather than those only in S-phase, changes in FLT may not correlate with Ki67 [12,21]. The MoA of everolimus also includes an important anti-angiogenic/vascular effect, which involves direct effects on the stroma and indirect effects through levels of VEGF [2], and this is likely to be responsible for the growth inhibition seen in vivo. Apparently, however, these stromal effects did not significantly affect uptake of the radiotracers. These observations prompted us to investigate the effects of other antiangiogenic agents in another model that had previously been used to study antiangiogenic/vascular agents [22,23] and compare them to the activity of a cytotoxic.

Effects of Other Compounds on FDG Tumor Uptake

Three other compounds with different MoA were tested for their ability to affect FDG uptake in a rat orthotopic mammary model, BN472. This model is well vascularized [22] and shows a good basal tumor uptake of FDG with a mean SUV of ca. 0.9 [12].

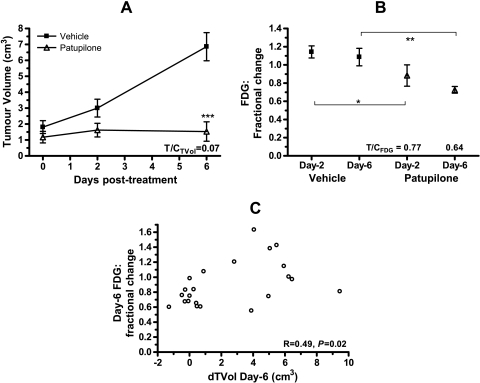

The micotubule stabilizer patupilone strongly inhibited BN472 growth causing tumor stasis (Figure 6A), and this was associated with a rapid decrease in FDG uptake 2 days after treatment; an effect that increased with time (Figure 6B). On day 6, the changes in FDG correlated positively with the change in TVol (r = 0.49, P = .02), confirming this tracer as a good marker of the activity of cytotoxics (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Patupilone inhibits growth and FDG uptake by rat mammary BN472 tumors. Rat BN472 tumors were created by transplantation of viable tissue into the mammary fat pad and, after 2 weeks, were treated once with vehicle or patupilone (0.7 mg/kg i.v.). Results show the mean ± SEM for (A) efficacy (n = 12 per group) and (B) fractional change in FDG uptake compared with day 0 (n = 11 per group), where *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. (C) Pearson correlation between the fractional change in FDG uptake and the change in tumor volume (TVol) at the end point of day 6 compared with day 0.

A similarly strong antitumor effect on BN472 tumors was caused by daily treatment with the dual RAF/KDR (VEGF-R2) inhibitor NVP-AAL881 (Figure 7A). However, with this compound, there was no early change in FDG and only a nonsignificant trend for a decrease in FDG uptake after 7 days (Figure 7B). According to the dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging method for detecting macrophages, which uses ultra small iron particles (Sinerem), NVP-AAL881 actually decreased macrophage uptake in this model compared with vehicle at both days 3 and 7 (Figure 7C), suggesting that the absence of a decrease in FDG uptake was not caused by an influx of glycolytic macrophages that can follow chemotherapy [24]. This was confirmed by IHC at the end point (day 7), showing that iron covered 0.01% to 0.09% of the surface area, with no difference between the two treatment groups (both 0.04%). Iron was mainly located in mononuclear cells and in fibroblastic areas, with some iron found in the wall of blood vessels and none in necrotic areas. Double staining with the Perl Prussian blue reaction and ED1 elucidated the amount of free, that is, nonphagocytized iron, which showed that 86% was bound to macrophages with no significant difference between the groups.

Figure 7.

Effects of NVP-AAL881 on rat mammary BN472 tumors. Rat BN472 tumors were created by transplantation of viable tissue into the mammary fat pad and, after 2 weeks, were treated twice daily with vehicle or NVP-AAL881 (15 mg/kg p.o.). Results show the mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group) for (A) efficacy and (B) fractional change in FDG uptake compared with day 0, where ***P < .001. (C) A separate cohort of treated rats showing the relative Sinerem concentration (compared with day 0) in each tumor determined on day 3 and day 7 after treatment initiation. Rats were injected i.v. with Sinerem (8 µl/kg) 24 hours before measurements as described in the Materials and Methods section.

Previously, we have shown that the pan-VEGF-R inhibitor, PTK/ZK (vatalanib) dose-dependently inhibited BN472 growth [23]. Here, daily dosing with PTK/ZK did not cause tumor regression but still inhibited tumor growth after 7 to 9 days of treatment (Figure 8A), and this was not associated with any effect on FDG uptake at either day 2 or day 7 (Figure 8B and Figure W2). On day 9, the tracer FMISO was used to assess hypoxia in vivo. This showed that all of the tumors in both groups were hypoxic (all TMRR > 1.4), and PTK/ZK had no significant effect on hypoxia (Figure 8C). Although the two most hypoxic tumors had the lowest FDG values, there was no overall significant correlation between these two parameters (r = -0.22, P = .5, n = 12). Ex vivo analyses for caspase 3+ staining also showed no effect of the drug on day 9 (Figure 8D), consistent with previous observations in this model [18].

Figure 8.

Effects of PTK/ZK on rat mammary BN472 tumors. Rat BN472 tumors were created by transplantation of viable tissue into the mammary fat pad and after 2 weeks were treated daily with vehicle or PTK/ZK (200 mg/kg p.o.). Results show the mean ± SEM (n = 6 per group) for (A) efficacy and (B) fractional change in FDG uptake compared with day 0. On day 9, the PET tracer FMISO was injected i.v. (150 µl), and after 90 minutes, images were made of the tumor and muscle as described in the Materials and Methods section. (C) Results show the mean ± SEM ratio of tumor-muscle where hypoxic conditions are defined as a TMRR > 1.4. (D) Tumors were ablated, and IHC was performed for the percent of cells positive for caspase 3.

Discussion

We have shown that the mTOR inhibitor everolimus can rapidly decrease FDG and FLT uptake in solid tumors that had previously been characterized in vitro as sensitive tumors but that it did not decrease tracer uptake in tumors characterized as insensitive in vitro such as HCT116 and KB31. Similar observations have been reported for rapamycin on human tumor xenografts where decreases in FDG and FLT were linked to changes in hexokinase and thymidine kinase 1 expression [9]. However, in that report, rapamycin had no effect on the growth of the insensitive tumors in vivo even after 2 weeks of daily treatment. Here, and previously [2], we have shown that tumors characterized as insensitive in vitro can have significantly reduced growth in vivo in response to everolimus (median T/C = 0.43–0.48), an effect not much weaker than in the two sensitive tumor models (median T/C = 0.25–0.27). Such antitumor effects are typical of everolimus monotherapy, which tends to reduce tumor growth rather than cause regression [3]. These observations on antitumor efficacy, coupled with the demonstration that everolimus potently inhibits growth of endothelial and stromal cells in vitro, reduces VEGF release from tumor cells, and reduces tumor vascularization in vivo [2], suggest that inhibition of growth of HCT116 and KB31 tumors probably includes a substantial antiangiogenic/vascular action. Surprisingly, however, the growth inhibitory effect on HCT116 or KB31 in vivo could not be detected by changes in uptake of FDG and FLT, suggesting that, for some reason, these PET tracers cannot detect an antiangiogenic MoA. This is an important observation because the clinical effects of everolimus monotherapy are also characterized by stable disease rather than by partial or complete response, that is, tumor growth inhibition rather than regression [4].

These observations prompted us to compare the effect of other compounds that have antiangiogenic or cytotoxic action mechanisms on FDG uptake using an orthotopic mammary model: BN472. The BN472 model has been previously characterized as well vascularized, and both cytotoxic and antiangiogenic compounds can inhibit its growth [22,23,25]. Unfortunately, this model is not derived from a cell line, and thus, the in vitro sensitivity of everolimus could not be assessed, although experiments in vivo showed weak inhibition after 2 weeks of treatment suggesting an everolimus-insensitive tumor cell [25]. In the BN472 model, the microtubule stabilizer patupilone decreased FDG uptake at both early (day 2) and late time points (day 6) while causing tumor stasis. In contrast, NVP-AAL881, a compound that inhibits both RAF and the VEGF-R2 (KDR), failed to affect FDG uptake in the BN472 tumors despite causing tumor regression. The pan-VEGF-R inhibitor, PTK/ZK, also failed to reduce FDG uptake significantly despite inhibiting the growth of these tumors. Although these results are puzzling, there are several possible explanations that may contribute to this phenomenon. These include 1) increases in TBF and permeability affecting FDG and nutrient delivery, 2) a stress response by the tumor cell aiming to avoid apoptosis by increasing transport of various nutrients including glucose and thymidine, 3) decreases in plasma glucose causing a relative increase in the levels of FDG, 4) induction of hypoxia leading to stimulation of glycolysis through HIF-1, and 5) increases in the number of glycolytic macrophages that infiltrate the tumor [24,26–30].

Where the mechanism for FDG uptake has been studied, investigations demonstrate that the rate-limiting step is at FDG phosphorylation by hexokinase rather than FDG transport by glucose transporters such as Glut-1 [9,31,32]. This suggests that changes in TBF are unlikely to affect FDG uptake except perhaps under conditions where TBF is very low, for example, in human tumor xenografts [12]. However, everolimus has been shown to decrease TBF [33,34], and in the B16/BL6 model described here, we could find no effect at all on the parameter BFI, which is equivalent to TBF. Consequently, we reason that although we did not measure TBF in the xenograft models, it is unlikely that an everolimus-induced increase in TBF in the insensitive models, for example, through normalization [35], can explain the effects observed here. Furthermore, despite a low FDG SUV, the fact that Glut-1 levels were very high in the H596 xenograft (and were unaffected by everolimus treatment) is also suggestive that nutrient supply is not rate-limiting for FDG uptake. There was no evidence that everolimus caused apoptosis in the mouse models, and thus, a stress response of increased glucose or thymidine uptake (thus veiling a decrease in FDG or FLT uptake) is also unlikely to explain the effects we observed. Furthermore, everolimus tends to slightly increase plasma glucose levels [4] (and unpublished observations), which might cause a decrease in FDG uptake, although where the influence of plasma glucose has been reported [36–38], this is of the order of 10-fold increases in plasma glucose. Thus, small changes in plasma glucose are unlikely to affect our observations on FDG uptake. Hypoxia can be positively correlated with glycolysis, but this is not always the case [30], and we did not observe it in the BN472 model where there was also no effect of the antiangiogenic PTK/ZK on hypoxia, which might have veiled a decrease in FDG uptake. Finally, an influx of glycolytic macrophages after cell kill could also veil a decrease in FDG uptake. We did not measure macrophages in the xenograft experiments but, at least in the rat BN472 model, an increase in tumor macrophage content seemed not to be an explanation for NVP-AAL881 because macrophage levels were actually decreased as measured by a contrast-enhanced MRI method, and IHC indicated no change compared with vehicle.

Thus, taken all together, our results suggest that anti-angiogenic/vascular inhibition of tumor growth does not affect tumor uptake of FDG or FLT as measured by PET in vivo. This may be considered a surprising observation, and further clinical confirmation of this hypothesis is important. A small FDG-PET study of eight patients with NSCLC showed that everolimus induced FDG changes ranging from -72% to +34%, but correlations with patient outcome or investigations of antiangiogenic effects were not made [10]. Another report from phase 1/2 studies showed that FDG changes in response to rapamycin were unrelated to tumor response by RECIST [11]. We are not aware of any clinical FDG/FLT-PET studies with PTK/ZK or NVP-AAL881, and data for other agents broadly described as antiangiogenic are minimal [39]. The multikinase inhibitor sunitinib has been shown to significantly reduce FDG-PET in some, but not all, patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and generally, there was a strong correlation between progression-free survival and the early FDG-PET response in this indication [40]. However, this drug has a strong potency against cellular c-KIT and PDGF-R equaling that against VEGF-R2 [41–43], and thus, its activity is not limited to the stromal compartment of the solid tumor. Interestingly, the eponymous antiangiogenic agent, bevacizumab, when tested for clinical activity against tumor blood volume, flow, permeability, interstitial fluid pressure and FDG in a six patients, induced rapid changes in all but FDG, which only changed, if at all, after 3 months of treatment [44].

In conclusion, we have shown that the allosteric mTOR inhibitor everolimus can significantly decrease FDG and FLT uptake by tumors in mice that are inherently sensitive to the drug. However, in less sensitive models where anti-angiogenic/vascular mechanisms probably predominate, no effect on these tracers could be detected. In a rat model, antiangiogenics also failed to affect FDG uptake. These data suggest that FDG/FLT-PET may provide false-negatives for anti-angiogenic/vascular inhibition and, consequently, may not be suitable as early response markers for everolimus, other rapalogs, or pure antiangiogenic agents. Thus, although positive PET responses are always useful, negative PET responses for rapalogs and antiangiogenics would preclude PET being used to obtain an OBD. These conclusions warrant clinical testing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Caroline Fux and Christelle Gerard for their excellent technical assistance in IHC and Claudia Keller for her excellent technical assistance in PET imaging.

Footnotes

This article refers to supplementary materials, which are designated by Figures W1 and W2 and are available online at www.transonc.com.

References

- 1.Bjornsti M-A, Houghton PJ. The TOR pathway: a target for cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:335–348. doi: 10.1038/nrc1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane HA, Wood JM, McSheehy PM, Allegrini PR, Boulay A, Brueggen J, Littlewood-Evans A, Maira SM, Martiny-Baron G, Schnell CR, et al. The mTOR inhibitor RAD001 (everolimus) has anti-angiogenic/vascular properties distinct from a VEGF-R tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1612–1622. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Reilly T, McSheehy PM. Biomarker development for the clinical activity of everolimus (RAD001): processes, limitations, and further proposals. Transl Oncol. 2010;3:65–79. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grünwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Hollaender N, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korhonen P, Malangone E, Sherman S, Casciano R, Motzer R, Baladi JF, Haas T, Zuber E, Kay A, Lebwohl D. Overall survival (OS) of mRCC patients corrected for crossover using inverse probability of censoring weights (IPCW) and rank preserving structural failure time (RPSFT) models: two analyses from the RECORD-1 trial; Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; June 4–8, 2010; Chicago, IL. Abstract 4690. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price P, Saleem A, Aboagye W. PET in development and use of anticancer drugs. In: Valk PE, Bailey DL, Townsend DW, Maisey MN, editors. Positron Emission Tomography. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2003. pp. 829–841. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mabuchi S, Altomare DA, Cheung M, Zhang L, Poulikakos PI, Hensley HH, Schilder RJ, Ozols RF, Testa JR. RAD001 inhibits human ovarian cancer cell proliferation, enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis, and prolongs survival in an ovarian cancer model. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4261–4270. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cejka D, Kuntner C, Preusser M, Fritzer-Szekeres M, Fueger BJ, Strommer S, Werzowa J, Fuereder T, Wanek T, Zsebedics M, et al. FDG uptake is a surrogate marker for defining the optimal biological dose of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1739–1745. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei LH, Su H, Hildebrandt IJ, Phelps ME, Czernin J, Weber WA. Changes in tumor metabolism as readout for mammalian target of rapamycin kinase inhibition by rapamycin in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3416–3426. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nogová L, Boellaard R, Kobe C, Hoetjes N, Zander T, Gross SH, Dimitrijevic S, Pellas T, Eschner W, Schmidt K, et al. Downregulation of 18F-FDG uptake in PET as an early pharmacodynamic effect in treatment of non-small cell lung cancer with the mTOR inhibitor everolimus. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1815–1819. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma WW, Jacene H, Song D, Vilardell F, Messersmith WA, Laheru D, Wahl R, Endres C, Jimeno A, Pomper MG, et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography correlates with Akt pathway activity but is not predictive of clinical outcome during mTOR inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2697–2704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebenhan T, Honer M, Ametamey SM, Schubiger PA, Becquet M, Ferretti S, Cannet C, Rausch M, McSheehy PM. Comparison of [18F]-tracers in various experimental tumour models by PET imaging and identification of an early response biomarker for the novel microtubule stabiliser patupilone. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:308–321. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim WD, Ahn D, Oh Y, Lee S, Kil HS, Oh SJ, Lee SJ, Kim JS, Ryu JS, Moon DH, et al. New class of SN2 reactions catalyzed by protic solvents: facile fluorination for isotopic labeling of diagnostic molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16394–16397. doi: 10.1021/ja0646895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim JL, Berridge MS. An efficient radiosynthesis of [18F]fluoromisonidazole. Appl Radiat Isot. 1993;44:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/0969-8043(93)90110-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh WJ, Rasey JS, Evans ML, Grierson JR, Lewellen TK, Graham MM, Krohn KA, Griffin TW. Imaging of hypoxia in human tumors with [F-18]fluoromisonidazole. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)91001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudin M, McSheehy PM, Allegrini PR, Rausch M, Baumann D, Becquet M, Brecht K, Brueggen J, Ferretti S, Schaeffer F, et al. PTK787/ZK222584, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, reduces uptake of the contrast agent GdDOTA by murine orthotopic B16/BL6 melanoma tumours and inhibits their growth in vivo. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:308–321. doi: 10.1002/nbm.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rausch M, Baumann D, Neubacher U, Rudin M. In-vivo visualization of phagocytotic cells in rat brains after transient ischemia by USPIO. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:278–283. doi: 10.1002/nbm.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McSheehy P, Weidensteiner C, Cannet C, Ferretti S, Laurent D, Ruetz S, Stumm M, Allegrini PR. Quantified tumour T1 is a generic early response imaging biomarker for chemotherapy reflecting cell viability. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:212–225. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulay A, Rudloff J, Ye J, Zumstein-Mecker S, O'Reilly T, Evans DB, Chen S, Lane HA. Dual inhibition of mTOR and estrogen receptor signaling in vitro induces cell death in models of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5319–5328. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breuleux M, Klopfenstein M, Stephan C, Doughty CA, Barys L, Maira SM, Kwiatkowski D, Lane HA. Increased AKT S473 phosphorylation after mTORC1 inhibition is rictor dependent and does not predict tumor cell response to PI3K/mTOR inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:742–753. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landberg G, Tan EM, Roos G. Flow cytometric multiparameter analysis of proliferating cell nuclear antigen/cyclin and Ki-67 antigen: a new view of the cell cycle. Exp Cell Res. 1990;187:111–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(90)90124-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferretti S, Allegrini PR, O'Reilly T, Schnell C, Stumm M, Wartmann M, Wood J, McSheehy PM. Patupilone induced vascular disruption in orthotopic rodent tumor models detected by magnetic resonance imaging and interstitial fluid pressure. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7773–7784. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti S, Allegrini P, Becquet M, McSheehy P. Tumor interstitial fluid pressure as an early-response marker for anticancer therapeutics. Neoplasia. 2009;11:874–881. doi: 10.1593/neo.09554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spaepen K, Stroobants S, Dupont P, Bormans G, Balzarini J, Verhoef G, Mortelmans L, Vandenberghe P, De Wolf-Peeters C. [(18)F]FDG PET monitoring of tumour response to chemotherapy: does [(18)F]FDG uptake correlate with the viable tumour cell fraction? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:682–688. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schnell CR, Stauffer F, Allegrini PR, O'Reilly T, McSheehy PM, Dartois C, Stumm M, Cozens R, Littlewood-Evans A, García-Echeverría C, et al. Effects of the dual phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 on the tumor vasculature: implications for clinical imaging. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6598–6607. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rigo P, Paulus P, Kaschten BJ, Hustinx R, Bury T, Jerusalem G, Benoit T, Foidart-Willems J. Oncological applications of positron emission tomography with fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23:1641–1674. doi: 10.1007/BF01249629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haberkorn U, Belleman ME, Brix G, Kamencic H, Morr I, Traut U, Altmann A, Doll J, Blatter J, Kinscherf R. Apoptosis and changes in glucose transport early after treatment of Morris hepatoma with gemcitabine. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:418–425. doi: 10.1007/s002590100489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dittman H, Dohmen BM, Kehlbach R, Bartusek G, Pritzkow M, Sarbia M, Bares R. Early changes in [18F]FLT uptake after chemotherapy: an experimental study. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002;29:1462–1469. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0925-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mankoff DA, Muzi M, Krohn KA. Quantitative positron emission tomography imaging to measure tumor response to therapy: what is the best method? Mol Imaging Biol. 2003;5:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajendran JG, Mankoff DA, O'Sullivan F, Peterson LM, Schwartz DL, Conrad EU, Spence AM, Muzi M, Farwell DG, Krohn KA. Hypoxia and glucose metabolism in malignant tumors: evaluation by [18F]fluoromisonidazole and [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2245–2252. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0688-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aloj L, Caracó C, Jagoda E, Eckelman WC, Neumann RD. Glut-1 and hexokinase expression: relationship with 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose uptake in A431 and T47D cells in culture. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4709–4714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng J, Dunnwald LK, Schubert EK, Link JM, Minoshima S, Muzi M, Mankoff DA. 18F-FDG kinetics in locally advanced breast cancer: correlation with tumor blood flow and changes in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1829–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broillet A, Hantson J, Ruegg C, Messager T, Schneider M. Assessment of microvascular perfusion changes in a rat breast tumor model using SonoVue to monitor the effects of different anti-angiogenic therapies. Acad Radiol. 2005;12(suppl 1):S28–S33. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shinohara ET, Cao C, Niermann K, Mu Y, Zeng F, Hallahan DE, Lu B. Enhanced radiation damage of tumor vasculature by mTOR inhibitors. Oncogene. 2005;24:5414–5422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jain RK. Normalizing tumor vasculature with antiangiogenic therapy: a new paradigm for combination therapy. Nat Med. 2001;7:987–989. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wahl RL, Henry CA, Ethier SP. Serum glucose: effects on tumor and normal tissue accumulation of 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose in rodents with mammary carcinoma. Radiology. 1992;183:643–647. doi: 10.1148/radiology.183.3.1584912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindholm P, Minn H, Leskinen-Kallio S, Bergman J, Ruotsalainen U, Joensuu H. Influence of the blood glucose concentration on FDG uptake in cancer—a PET study. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keyes JW. SUV: standard uptake or silly useless value? J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1836–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Besse B, Armand J-P, Soria J-C. Targeting angiogenesis with oral agents. Ann Onc. 2006;17(suppl 10):x71–x75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prior JO, Montemurro M, Orcurto MV, Michielin O, Luthi F, Benhattar J, Guillou L, Elsig V, Stupp R, Delaloye AB, et al. Early prediction of response to sunitinib after imatinib failure by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:439–445. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, Louie SG, Christensen JG, Li G, Schreck RE, Abrams TJ, Ngai TJ, Lee LB, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, Pryer NK, Cherrington JM. SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu-Lowe DD, Zou HY, Grazzini ML, Hallin ME, Wickman GR, Amundson K, Chen JH, Rewolinski DA, Yamazaki S, Wu EY, et al. Nonclinical antiangiogenesis and antitumor activities of axitinib (AG-013736), an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 1, 2, 3. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7272–7283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willett CG, Boucher Y, di Tomaso E, Duda DG, Munn LL, Tong RT, Chung DC, Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Kozin SV, et al. Direct evidence that the VEGF specific antibody bevacizumab has antivascular effects in human rectal cancer. Nat Med. 2004;10:145–147. doi: 10.1038/nm988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Reilly T, McSheehy P, Kawai R, Kretz O, McMahon L, Brueggen J, Bruelisauer A, Gschwind H, Allegrini P, Lane H. Comparative pharmacokinetics of RAD001 (everolimus) in normal and tumor-bearing rodents. Cancer Chemother Pharm. 2009;65:625–639. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.