Abstract

Although automobiles remain the transportation of choice for older adults, late life cognitive impairment and dementia often impair the ability to drive safely. There is, however, no commonly utilized method of assessing dementia severity in relation to driving, no consensus on the assessment of older drivers with cognitive impairment, and no gold standard for determining driving fitness. Yet, clinicians are called upon by patients, their families, other health professionals, and often the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) to assess their patients' fitness-to-drive and to make recommendations about driving privileges. Using the case of Mr W, we describe the challenges of driving with cognitive impairment for both the patient and caregiver, summarize the literature on dementia and driving, discuss evidenced-based assessment of fitness-to-drive, and address important ethical and legal issues. We describe the role of physician assessment, referral to neuropsychology, functional screens, dementia severity tools, driving evaluation clinics, and DMV referrals that may assist with evaluation. Finally, we discuss mobility counseling (eg, exploration of transportation alternatives) since health professionals need to address this important issue for older adults who lose the ability to drive. The application of a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach to the older driver with cognitive impairment will have the best opportunity to enhance our patients' social connectedness and quality of life, while meeting their psychological and medical needs and maintaining personal and public safety.

The Patient's Story

Mr W is 92-years-old retired college professor who lives at home with his wife, in an upscale suburban neighborhood that offers little public transportation. Although his wife can operate a motor vehicle, she prefers Mr. W to drive. Mr W has obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension treated with lifestyle modification, treated vitamin B12 deficiency, mild chronic anemia, restless leg syndrome, osteoporosis, edema, and a history of prostate cancer. His only medication is vitamin B12.

About 8 years ago, the patient reported mild forgetfulness to his geriatrician, Dr D. In 2004, Mr W reported that he had lost his way while driving to a familiar museum, had difficulty recalling details of his personal art collection, and had fallen a few times. His score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) 1 was 30/30.

In January 2009, he reported that his memory loss troubled him and that driving had become more difficult. He had no driving violations, and neither he nor his wife reported unsafe driving practices. He could independently perform all basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and walked a quarter mile without difficulty. The MMSE was now 29/30. Neuropsychological testing was consistent with “mild cognitive impairment” (MCI). Dr D thought the MCI might be due to early Alzheimer disease (AD) and recommended assessment at a driving evaluation clinic.

Perspectives

Mr W and his wife, and Dr D were interviewed by a Care of the Aging Patient editor in May 2009.

Mr W: I can't remember where I put things, or what is the best route to take to get from here to there. … Things that … I've done automatically, all of a sudden requires effort. It's a very frustrating life… I don't expect to get permanently lost anywhere. …I think I'm a safe driver.

Mr W's wife: We see lots of new places in the city we've never seen before.

Introduction

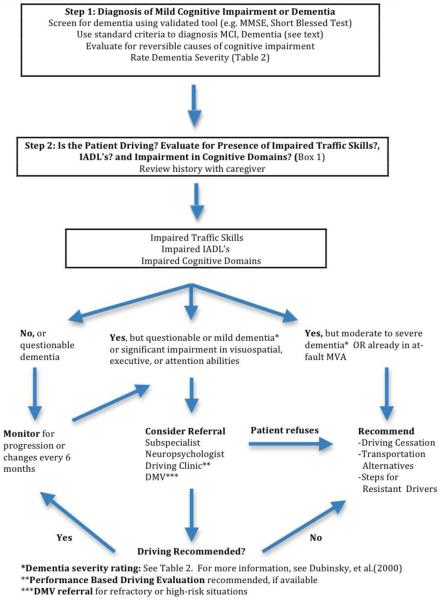

In this article we present an evidenced-based approach to the evaluation, assessment, and counseling of older drivers with cognitive impairment (Figure). We define and describe 2 levels of cognitive disorder in older adults: MCI and dementia. We review studies that have examined functional abilities and traffic skills in drivers with dementia, identify co-morbidities that can further reduce driving competence, examine options for driving evaluation, and finally, discuss key aspects of mobility counseling to inform patients of transportation alternatives.

Figure.

Evidence-Based Approach to the Assessment of Older Adult Drivers with Cognitive Impairment/Dementia

Methods

We searched Medline for cognitive domains, specific psychometric tests, and driving outcomes. Key search terms incorporated limits of “human” and “English language.” We included studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 1994 and September 10, 2009 that included participants who had Alzheimer disease or dementia as diagnosed by standardized cognitive tests and were studied with standard driving outcomes measures, eg, on-road driving assessment, simulator, or crash data. The search terms utilized included: driving outcomes, eg, “automobile driving,” “computer simulation,” “road tests” (text word), “automobile driver examination,” “accidents--traffic”; and participant characteristics eg, “cognitive impairment,” “dementia,” “Alzheimer's disease,” “frontal lobe syndromes,” and “Lewy body disease.” Our data synthesis and recommendations were also informed by our clinical experience caring for dementia patients in the outpatient setting.

Epidemiology

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a syndrome defined by abnormal function in a specific cognitive domain (eg, memory, language), deviation from the norm on a standardized psychometric test related to the specific cognitive domain, and the absence of impairment in daily activities.2 Preliminary studies indicate there may be impairment in driving skills in MCI.3,4 However, more evidence from research studies is needed on MCI to inform recommendations in regards to monitoring or assessing driving skills.

In contrast, dementia is manifested by the onset of impairment in memory, requires the presence of impairment in at least 1 additional cognitive domain, and those deficit(s) cause significant impairment in social and/or occupational functioning. Approximately 4% of current drivers over age 75 years have a dementia,5 and many of these continue to drive well into the disease process.6 In a study where older adults were administered a well-validated brief cognitive screen to detect dementia, nearly 20% of those over age 80 years failed.7

Dementia and Driving Outcomes

Studies examining crash rates in drivers with dementia compared with controls are summarized in Table 1. Evidence from motor vehicle crash studies suggests that drivers with a dementia have at least a 2-fold greater risk of crashes compared to cognitively intact older adults, but this increased risk is not found in all studies. The variability in findings can be explained in part by the definitions of crashes (self-report vs. state recorded), settings (tertiary referral centers vs. license renewal settings) and referral bias. Overall, the risk of a crash for AD appears to increase with the duration of driving after disease onset.

Table 1.

Published Motor Vehicle Crash Rates in Samples of Older Normal and Older Cognitively Impaired Drivers

| Dementia severity (N) |

Locale | Ascertainment method |

Mean MMSE (S.D.) |

Mean age (S.D.) |

MVA/driver/ Year (S.D.) |

MVA/driver/ 1,000 miles (S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (98)66 | Kansas City, KS |

Questionnaire | 29.4 + 0.8 | 64.6 ± 9.4 | .06 (.24) | .014 (.044) |

| Moderate dementia (19) |

Kansas City, KS |

Questionnaire | 17.3 ± 7.1 | 71.3 ± 8.3 | .11 (.35) | .263 (.741)* |

| Normal (44)12 | Pawtucket, RI |

Questionnaire + state records |

29.1 ± 1.1 | 73.5 ± 9.1 | .04 | .005 |

| Very mild- mild dementia, CDR 0.5-1 (84) |

Pawtucket, RI |

Questionnaire + state records |

24.1 ± 3.6 | 75.7 ± 7.0 | .06 | .017* |

| Normal (58)67 | St. Louis, MO | State records | NA | 77.0 ± 8.6 | .07 | .091 |

| Very mild dementia CDR .5 (34) |

St. Louis, MO | State records | NA | 73.7 ± 7.0 | .06 | .097 |

| Mild dementia CDR 1 (29) |

St. Louis, MO | State records | NA | 74.2 ± 7.8 | .04 | .110 |

| Normal (24)68 | Los Angeles, CA |

Interview + state records |

29.2 + 0.5 | 71.8 + 6.8 | NA | .028 |

| Mild dementia (13) |

Los Angeles, CA |

Interview + state records |

23.2 ± 2.6 | 70.7 ± 7.4 | NA | .214** |

| Normal (249)69 | Vancouver, BC, Canada |

State records/insurance claims |

NA | 62-69 | .06 | NA |

| Cognitively impaired not demented (84) |

Vancouver, BC, Canada |

State records/insurance claims |

NA | 62.5 ± 10.5 | .14 | NA |

| Mild dementia (165) |

Vancouver, BC, Canada |

State records/insurance claims |

NA | 69.2 ± 7.3 | .15* | NA |

| Normal (715)70 | Ann Arbor, MI |

State records | NA | 70.8 ± 7.8 | .08 | NA |

| Mild to moderate dementia (143) |

Ann Arbor, MI |

State records | 14.8 ± 6.4 | 70.9 ± 7.7 | .08 | NA |

| Normal (83)71 | Seven national regions |

Questionnaire | NA | 72.1 ± 8.0 | .04 | NA |

| Mild to severe dementia (83) |

Seven national regions |

Questionnaire | NA | 70.1 ± 8.5 | .09* | NA |

| Normal (20)72 | Bethesda, MD |

Questionnaire | NA | NA | .02 | NA |

| Mild dementia (30) |

Bethesda, MD |

Questionnaire | 19.9±6.3 | 67.8+11.0 | .09* | NA |

| Normal (31)73 | Mendoza Argentina |

Questionnaire | 28.5±1.6 | 60.8±10.3 | .02 | NA |

| Dementia (56) | Mendoza Argentina |

Questionnaire | 18.5±6.0 | 71.8±8.1 | .NA | NA |

p<.05, comparing dementia patients to controls

MVA + moving violations; significance not assessed

In driving simulation studies, drivers with AD consistently perform more poorly than do non-demented controls,8 are more likely to drive off the road, drive more slowly than the speed limit, apply less brake pressure when trying to stop, and make slower left turns.9 Studies from the National Advanced Driving Simulator at the University of Iowa analyzed vehicle maneuvers related to simulated crashes and demonstrated that inattention and either slow or inappropriate responses were major factors leading to accidents.10 Simulators are still best viewed as a research tool and not as a sole determinant of driving fitness.

Performance-based road tests are another measure of driving competency. Most of these studies report on qualitative outcomes (eg, “pass/fail” rates) in comparison to controls, but some studies have used point systems or quantitative outcomes.11, 12 Demented drivers have particular difficulties with lane checking and changing,13 merging, left turns, signaling to park,14 and route following.15

The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), a global measure of dementia severity, uses a semi-structured interview and exam to rate the severity of the dementia.16 Pooled data from 2 longitudinal studies involving 134 drivers with dementia17,12 show that 88% of drivers with very mild dementia (CDR = 0.5) and 69% of drivers with mild dementia (CDR = 1.0) are still able to pass a formal road test. Moreover, the median time to cessation of driving for those with very mild dementia was 2 years, and for those with mild dementia, 1 year.

The majority of studies on dementia and driving have focused on AD, however other degenerative dementias are not uncommon, and may negatively impact driving fitness. In a prospective road test study of controls and mixed medical disorder patients with AD, vascular dementia, and diabetes, driving performance errors were comparable between AD and vascular dementia patients. 18 This suggests that degree of cognitive impairment rather than dementia diagnosis is the more important determinant of risk. Disinhibited and agitated behaviors in patients with frontotemporal dementia have been shown to cause hazardous driving, 19 perhaps to an even greater extent than behaviors typically exhibited by drivers with AD. Prominent visuoperceptual and attention deficits, as well as the common occurrence of visual hallucinations and fluctuating levels of alertness may raise significant concerns about driving safety for patients with Lewy body dementia.

Approaches to Evaluating Driving Safety

Mr W: I've driven around with my wife, who is supervising my driving to be sure that I'm behaving in a reasonable fashion. I've gone to the DMV and gotten the book of driving rules so I can pass the written exam without any trouble.

Mr W's wife: I find my husband to be a very good driver. His reaction time appears to me to be very good. He obeys the law. He doesn't speed. He's alert… He's going to pass any test they're going to give him.

Dr D: The first stage is just recognizing general cognitive impairment, whether it's a memory problem, judgment problem, or visual-spatial problem. Once I do that medical assessment, the next step is to try to sort out whether or not these deficits may be affecting someone's ability to drive.

The clinical opinion of a primary care physician or subspecialist, evidence of a recent crash, new onset of impaired driving behaviors noted by caregivers, functional impairment as measured in key cognitive domains, impairment in performance-based evaluations such as road tests, and difficulty with simulator scenarios have all been used in various settings to risk stratify or assess fitness-to-drive in individuals with a dementing illness. These issues will be discussed in subsequent sections.

Our approach to evaluating older adults with cognitive impairment or dementia is described in the Figure. The initial efforts focus on confirming a diagnosis, evaluating the individual for reversible causes for cognitive decline, rating dementia severity, determining if the patient is still driving, and identifying co-morbidities. Next steps in the evaluation process include queries about impairments in traffic skills that could be attributed to dementia (Box 1), the assessment of functional status, and evaluating specific cognitive domains (eg visuospatial skills, executive function) by psychometric testing. Finally, consultation with other health professionals to obtain further opinions on fitness-to-drive and/or provide counseling for transportation alternatives is considered.

Box 1. Assessing Patients for Driving Safety.

History: Ask Caregivers

Have they had any motor vehicle accidents?

Have they had any “near misses”?

Have they had any tickets?

Have they been pulled over by police?

Have you noticed a change in driving behaviors from baseline? Since last exam?

Have they had difficulty staying in your lane?

Do they have difficulty following the rules of the road?

Do other drivers honk at them?

Are there scratches on the car?

Have they gotten lost in familiar areas?

Are they vigilant in scanning for vehicles/pedestrians?

Physical Examination: Assessment for co-morbid conditions that can further reduce capacity

Visual: cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, glaucoma

Cognitive: sleep apnea, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, psychiatric disease, diabetes

Motor: degenerative joint disease, muscle weakness, neuropathy

Medication Review: Assessment for sedating agents

Antihistamines

Antipsychotics

Tricyclic antidepressants

Bowel/bladder antispasmodics

Benzodiazepines

Muscle relaxants

Barbiturates

Functional Assessment: Assessment of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Food Preparation

Finances

Telephone

Medications

Shopping

Housekeeping

Laundry

Although many demented individuals have difficulty in actual driving situations, most patients early in the course of dementia are still able to pass a driving performance test. Therefore, a diagnosis of dementia should not be the sole justification for the revocation of a driver's license. However, if a patient has degenerative dementia—eg, even in the initial stages of AD—the physician should begin the conversation about the inevitability of future driving cessation. This conversation, including planning for transportation alternatives (discussed below), should occur early in the diagnosis. We have found that in our practice, when the repeating the message to the patient and caregiver may reduce the possibility of resistance or noncompliance with future directives.

Physician Evaluation, Functional Assessment, and the Rating of Dementia Severity

Dr D: This loss, whether it's … because of cognitive ability or [whether] someone's had a disabling stroke or [whether someone] has such severe arthritis that they literally can't turn their neck rapidly enough to safely scan their environment, is unlikely to affect just this single functional domain … it would be foolhardy to look at this in isolation. Unfortunately, I don't know of any tool that has been validated to [assess driving competency in the office]. I use my own mental checklist.

From a practical standpoint, the assessment and opinion of the primary care physician or subspecialist may be the only evaluation available or acceptable to the patient, caregiver, or community. Caregivers of demented patients, when queried, want their physicians to assist and provide guidance in this area.20

In the office setting, physicians have been studied systematically to assess their accuracy in predicting driving ability in a sample of older adults. In one study, six clinicians with varying levels of experience and expertise in dementia care were asked to predict road test performance in 50 drivers with dementia, based on their examination of driving behaviors and clinical records (demographics; driving exposure and experience; history of accidents and violations; physical, eye, and neurologic examinations; neuropsychological tests). Inter-rater reliability and accuracy (percentage of correct positive and negative classifications) were modest, with accuracy ranging from 62-78%. The most accurate were clinicians specially trained in dementia assessment, not necessarily those with the most years of clinical experience.21

The CDR, as noted above, has been shown to stratify driving risk in 2 large-scale longitudinal studies and has been recommended for clinical use to determine fitness to drive.22 Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) are a global measure of dementia severity often used in clinical practice that may serve as a proxy for driving ability. In 1 study, among drivers with reduction of at least 30% in their total IADL score, 75% were regarded by their caregivers as unable to drive safely.23 We offer a summary of the descriptive elements of the CDR that combine both cognitive and functional domains based on the level of dementia severity in Table 2.

Table 2.

| Clinical Measure of Dementia Severity |

No Dementia (CDR=0) |

Questionable or Very Mild Dementia (CDR=0.5) |

Mild Dementia (CDR=1.0) |

Moderate Dementia (CDR=2.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | No memory loss or inconsistent memory loss |

Consistent slight forgetfulness |

Memory loss interferes with everyday activities |

Moderate memory loss |

| Fully oriented | Slight difficulty with orientation or judgment |

Geographic disorientation |

Severe difficulty with time relationships and judgment |

|

| Judgment intact | Moderate impairment in judgment |

|||

| Functional Assessment |

Function intact | Slight impairment in community activities or home activities |

Mild but definite impairment of community or home activities |

No longer independent in activities Only simple chores preserved |

| Personal care intact |

Personal care intact | Needs prompting for personal care |

Needs assistance in personal effects |

|

Clinical Dementia Rating training available at; http:alzheimer.wustl.edu/cdr/default.htm

National Guidelines and Physician Practice

Consensus among national medical, transportation, and elder advocacy societies is that drivers with moderately severe dementia should not drive (Table 3), as confirmed by studies of road testing at varying levels of dementia severity.24 There is still debate among experts on whether drivers with mild dementia should be allowed to drive and under what circumstances or restrictions, although recent literature does indicate that some patients with mild dementia may be able to pass a performance-based road test.

Table 3.

Expert Recommendations of Professional Societies and Consensus Meetings

| Expert Group | Driving Cessation Recommended |

Specialized or Detailed Assessment Recommended |

Other Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| The 1994 International Consensus Conference, 199474 |

Moderate to severe dementia |

Mild dementia: consider specialized assessment of driving competence. |

|

| American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline, 199775 |

Moderate to severe impairment Mild dementia plus significant deficits in judgment, spatial function, or history of at-fault motor vehicle |

Patients with milder impairment should be urged to consider giving up driving. |

|

| American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry, Alzheimer's Association, American Geriatric Society, 199776 |

Advanced dementia | Patients with a history of traffic mishaps or more significant spatial and executive dysfunction |

|

| Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia,199977 |

Patients with AD should plan early for eventual cessation of driving. Physicians should advocate for the establishment and access to affordable, validated performance-based driving assessments. |

||

| American Association of Automotive Medicine/ National Highway Transportation Safety Association Consensus meeting: Guidelines for physicians, 200078 |

All patients: Based on focused medical assessments, physicians should encourage early planning for eventual cessation of driving in persons with dementia. |

Physicians should advocate establishment and access to affordable, validated, and performance-based driving assessments. |

|

| American Academy of Neurology: Practice parameter, 200022 (currently under revision) |

Mild dementia defined as Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) = 1 or greater (Standard) |

Questionable or very mild dementia defined as CDR = 0.5: referral for a driving performance evaluation by a qualified examiner (Guideline) |

Reassess every 6 months (Standard) |

| Alzheimer's Association: Position statement, 200179 |

When the individual poses a serious risk to self or others. |

If there is concern that an individual with AD has impaired driving ability, and the person would like to continue driving: perform a formal assessment of driving. |

A diagnosis of AD is not, on its own, a sufficient reason to withdraw driving privileges. The determining factor should be an individual's driving ability. |

| American Medical Association: Physician's Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers, 200380 |

All patients: office-based measures to guide recommendation for driving cessation or performance-based assessment |

With early diagnosis, plan early for a smooth transition from “driving” to “non-driving” status. Co-pilots should never be recommended to unsafe drivers as a means to continue driving. |

|

| American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry: Position statement, 200681 |

Strongly consider for all patients with AD, even in mild dementia. |

Those with very earliest manifestations of dementia: refer for driving performance evaluation by a qualified examiner |

Reassess dementia severity and appropriateness of continued driving every six months. |

| Canadian Medical Association: Driver's guide, 200682 |

Moderate-to-severe dementia |

Mild dementia: comprehensive off-road and on-road test at a specialized driving center |

Patients deemed fit to drive should be re- evaluated and possibly retested every 6 to 12 months. |

Co-morbidities and Medications

Mr W's wife: We are aware of the fact that this memory loss, a large part of it, came with dosing with psychoactive drugs and lack of sleep. We are in the process of remedying the apnea. We think, from experiences we have had, that once he catches up on his sleep, things are going to be improved.

This observation from Mr W's wife underlies the importance of identifying and/or treating reversible causes of cognitive decline. The influence of multiple medical illnesses or co-morbidities on further impairing driving ability in patients with dementia has not been well studied, but should be considered when evaluating driving competency. Two publications in the past decade summarize the extensive literature on medical conditions and driving impairment,25,26 and recently the AMA published an update in this area in their guide on older drivers.27

Medical conditions associated with impaired driving ability include: diseases affecting vision (eg, cataracts, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, glaucoma), cardiovascular diseases (eg, angina pectoris), respiratory diseases (eg, sleep apnea, COPD), neurologic diseases (eg, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, Parkinson disease), psychiatric diseases (eg, depression, psychosis), metabolic diseases (eg, hypoglycemia), and musculoskeletal diseases (eg, cervical spine arthritis). Side effects of various medications28 have been associated with impaired driving and these should be avoided or minimized when operating a motor vehicle. These medications include sedating agents in the following classes of drugs: anti-convulsants, antihistamines, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, bowel/bladder antispasmodics, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, and barbiturates.29 Focus on co-morbidities should include conditions that are chronic and irreversible and those that are amenable to interventions. Surgical correction of cataracts, treating obstructive sleep apnea, and removing sedating medications are examples of interventions that have shown potential to improve driving safety with our older adults.

Driving Habits/Traffic Skills

Mr W and his wife are confident of his driving ability. Many patients with cognitive impairment do not have insight into their driving abilities. Unlike Mrs. W, many caregivers do express concerns about the driver with cognitive impairment. Studies of the validity and accuracy of informant reports show mixed results.30 With specific questioning family members may be a good source of information about abnormal driving behaviors. 31 Specifically, the physician may ask family members about crashes, citations, close calls, following the rules of the road, and whether the patient becomes lost while driving in familiar area. We routinely obtain information on the development of new onset impaired traffic skills in our older adults with the dementia, but acknowledge the dearth of evidence that has studied these changes as a predictor of unsafe driving.

Box 1 summarizes questions about traffic skills and important aspects of the past medical and social history that may help to assess at-risk driving behavior and conditions or medications that may further reduce driving capacity.

Psychometric Tests

The MMSE was not designed to assess driving capacity. Studies regarding the utility of global cognitive measures like MMSE for estimating driving impairment have been mixed.32 Although the MMSE may correlate with degree of driving impairment on road tests and history of crashes, it does not appear to predict future involvement in crashes, and valid cutoff scores have not been defined.33

In 2004, a meta-analysis of neuropsychological tests of driving performance in patients with dementia concluded that tests of visuospatial skills are the most relevant predictors of driving impairment.34 More recently, visuomotor and executive function tests such as trailmaking and maze completion35,36 have been associated with driving impairment in older adults with dementia. The American Medical Association (AMA) recommends that physicians adopt the Assessment of Driving-Related Skills (ADReS) battery to risk stratify older adults as to their driving abilities.27 This battery includes testing visual fields by confrontation, visual acuity by the Snellen eye chart, adopting the Clock Drawing Task, Trails B (a test of visuospatial and psychomotor speed), muscle strength, and neck and extremity range of motion. Individual test characteristics of the ADReS battery have been studied in older adults 37 and the Trails B test and the Rapid Pace Walk have been associated with a prospective increased risk of an at-fault crash.38 Data from one AMA-based dementia education program suggests that some physicians may be willing to adopt such tests.39 However, to our knowledge, the test battery as a whole has not been validated using driving outcomes either in primary care practice settings or in samples of demented drivers. Encouraging studies have been published on the association of other cognitive tests (eg UFOV/selected and/or divided attention and visual closure tasks) with prospective at-fault crash rates in community samples,40 that presumably also include older adults with dementia or MCI.

Table 4 summarizes published predictive values of some psychometric tests in determining the ability to pass a road test in older adults with dementia. Unfortunately, detailed information on the sensitivity, specificity, and classification accuracy of psychometric tests are lacking in most studies.41 Overall, most traffic safety experts conclude that psychometric tests may serve to identify drivers at-risk, but should not be the sole determinants in deciding to continue or revoke driving privileges.33

Table 4.

Predictive Values of Neuropsychological Tests and Test Batteries for Road Test Performance

| Test(s) | Sample | Outcome measure |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy (% Correctly Classified) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computerized mazes83 |

Normal + AD (CDR .5-1) |

Road test | NA | NA | 68.6 |

| Computerized mazes+ Hopkins Verbal Learning+Age83 |

Normal + AD (CDR .5-1) |

Road test | NA | NA | 81.0 |

| Maze Navigation35 | Normal + AD (CDR .5) |

Road test | NA | NA | 80.0 |

| Maze Task84 | MCI + mild AD | Road test | 77.8 | 82.4 | 77.4 |

| Driving Scenes of Neuropsychological Assessment Battery85 |

Normal + AD (CDR .5) |

Road test | NA | NA | 66.0 |

| Eight test battery86 | Mixed dementia |

Road test | 80.0 | 61.5 | 76.2 |

NA: Not Available

Communication and Counseling

Dr D: We talked about it in a couple of different ways. … In fact, I think part of him almost welcomed it … I got the sense that at some level he wasn't sure that he should still be driving.

Given the negative impact that occurs when older adults stop driving and the lack of viable public transportation resources, physicians should encourage ongoing driving when appropriate and plan a reassessment within a limited time frame. Physician advice is one of the more frequently cited reasons that a patient stops driving. Although the conversation between Dr D and Mr W went smoothly, patients may become irate, angry, or defensive. However, physicians can focus on other important areas of driving safety to put the issue in context. As with all patients, physicians should remind patients with cognitive impairment and their caregivers to use seat belts, refrain from ingesting any alcohol before operating a motor vehicle, and to avoid multitasking while driving (eg, using cell phones). From an ethical, policy, and legal standpoint, physicians should remind the patient and their caregiver that they may have a responsibility to notify the Department of Motor Vehicles and/or their insurers as to the presence of a dementia and its potential to impact driving safety.

If the patient becomes angry when told by the physician that he or she should no longer be driving, the physician should allow time for “ventilation” and/or dissipation of anger. Communication about this issue must be done in a sensitive and respectful manner. Comments such as, “we can agree to disagree” or “let's follow you over time and see how the new medication works” may defuse a potentially emotional situation. Suggestions for managing the recalcitrant driver who the physician believes should stop driving appear in Box 2. To our knowledge, these types of interventions have not been systematically studied, but have been adopted with modest success in our clinical practices.

Box 2. Steps Family Members can Take to Ensure that a Resistant Demented Patient no Longer Drives.

Approaches involving physician

-Ask physician to “prescribe” driving cessation orally and in writing

-Ask physician to use medical conditions other than dementia as the reason to stop driving (eg, vision too impaired, reaction time too slow)

-Use a contract (see At the Crossroads guide in Web Resources)

Vehicle-related approaches

-Hide/file down or replace the car keys with keys that will not start the vehicle

–Do not repair the car/or send car for “repairs” but arrange for its removal

–Remove the car by loaning, selling to third party, or donating vehicle to charity

–Disable the car

Financial and legal tactics

-Ask family lawyer to discuss financial and legal implications of crash or injury to patient, family or third party

-Refer to the Department of Motor Vehicles

Family members may try to compensate by having a non-impaired driver serve as “co-pilots.” There is some evidence suggesting that the crash rate of demented patients is lower with another person in the car,42 however data are insufficient to support this practice as a compensation mechanism for demented drivers. In addition, some clinicians may be tempted to recommend limiting trips or driving only under safe conditions, such as avoiding rush hour, in climate weather, driving during the day, or limiting trip time and/or distance. Restricted licenses have been associated with reduced crash risk.43 However, many older adults are already restricting or limiting their driving, and it is doubtful that a patient with dementia could retain such instructions.

Finally, there is a wealth of educational curricula geared to health professionals, such as the AMA's Older Driver Project.Error! Bookmark not defined.36 Two recent education interventions for health professionals were positively associated with increased comfort in discussing driving with patients with dementia, reporting unsafe drivers, or adopting tools that might be of use in the assessment process.39,44

Referral

Dr D: There are various services in the area that are typically staffed by a physical therapist or an occupational therapist, where they conduct … driving evaluations and driving simulations that I just don't have the ability to do here in the office. We can get objective information about their relative strengths and weaknesses and I can make a determination about the next step. [Mr W] is in the process of having this preliminary evaluation done by the (driving rehabilitation) therapist. I fear that they're going to tell me that he should stop driving. I suspect the next step will be reporting him to the Department of Motor Vehicles.

In the absence of a gold standard or consensus for determining driving competency, Dr D, like many clinicians, may request assistance from a driving clinic or refer to other subspecialists in the community (eg, geriatricians, psychiatrists, neurologists, neuropsychologist).

A Driver Rehabilitation Specialist (DRS) evaluates, develops, and implements driving services for individuals with disabilities. DRSs are often occupational therapists with additional training in driver evaluation, vehicle modification, and rehabilitation, but may also be trained in physical therapy and psychology. Occupational therapy practice guidelines for these evaluations have been published.45 However, a recent review of practices across the US and Canada indicates that although the same domains are generally assessed, specific assessments vary significantly across programs and few have adopted standardized tools.46

A typical driving evaluation may last several hours and often includes off-road tests of vision, cognition, and motor skills. The on-road assessment is typically performed in a driver rehabilitation vehicle equipped with a dual set of brakes. The driving evaluation usually costs $350-$500 and is generally not covered by insurance. Clinicians who are interested in this service can contact the occupational therapy departments in local hospitals or rehabilitation centers or the ADED directory (see, online Web resources).

We recommend a performance-based road test for demented drivers with a) caregiver observation of new impairments in traffic skills, b) prominent impairments in key cognitive domains (eg, attention, executive function, visuospatial skills), or c) the presence of a mild dementia (CDR=1). Private or university-based driving clinics are not available to everyone across the country, but every state Department of Motor Vehicles conducts performance-based road tests.

Some clinicians may be reluctant to refer their patients for road testing, since this procedure is rarely standardized and the data supporting their use may be limited. However, the ability to demonstrate proficiency behind the wheel in traffic is a practical method of evaluation, is the defacto method adopted by all 50 states to evaluate novice and medically impaired patients, and evidence is gathering that those that pass these tests have acceptable prospective crash rates.

Development of uniform standards for road testing and simulators may improve outcomes.47 A recent review concluded there was simply no evidence to demonstrate the benefit of driving evaluations with respect to the preservation of mobility or a reduction in crashes.48 However, more recent studies are encouraging. For example, in a longitudinal study based at an academic medical center, crash rates for drivers with dementia declined to the levels of healthy control drivers during a period of 3 years when evaluated with road tests every 6 months.12 The costs of such detailed surveillance as repeat road testing may be prohibitive, however, and it is unknown whether community-based road testing programs would produce similar results.

Mobility Counseling

Dr D: One of the disadvantages of living in this community is that public transportation is… basically nonexistent, so realistically, people live [by driving] their cars.

Mr W: [It] would be a catastrophe if [my license is taken away]. [Without] access to an automobile, we'd either have to hire a full-time chauffeur, which we can't afford to do, or simply sell the house and move someplace else.

This concern about the lack of driving alternatives and the fear of losing social connectivity expressed by Dr D and Mr W is universal. Driving cessation has been associated with a decrease in social integration,49 decreased out-of-home activities,50, 51 an increase in depressive symptoms in the elderly,52 anxiety symptoms,53 and an increased risk of nursing home placement.54 Planning for driving retirement should occur for all older adults before their mobility situation becomes urgent.55 Referral to a social worker may assist with identifying community transportation needs. Many organizations are available to assist clinicians, patients and families with these issues (see web resources).

The Physician's Legal and Ethical Obligations

Many physicians are uncertain of their legal responsibility to report unsafe drivers to the state56 As Dr D noted, his state requires mandatory reporting of patients with diagnosed dementia, but this mandate represents the minority view across US jurisdictions. Most states have voluntary reporting, where referral is an option, but one that should be considered in some situations. The Departments of Motor Vehicles or Revenue in all states often use the road test as the final or major arbitrator to determine licensing. Many authorities recognize the performance-based road test as the de facto standard.57 However, a recent study reporting licensing outcomes in Missouri noted that very few (<4%) older adults referred for fitness-to-drive evaluations (40% of whom had a dementing illness) were able to retain their license.58 Thus, referrals in some states may reflect more of a delicensing process.

The AMA's policy states, “in situations where clear evidence of substantial driving impairment implies a strong threat to patient and public safety, and where the physician's advice to discontinue driving privileges is ignored, it is desirable and ethical to notify the Department of Motor Vehicles.”59 Obviously, it is preferred that referrals to DMV be done with the patient's knowledge, and that the report be documented in the medical record. However, many primary care physicians, fearing the deterioration of a long-standing relationship with their patient, may be reluctant to be this forthcoming. If a physician decides to report an unsafe driver, most states will accept a formal letter. Specific forms may be available on-line or at the DMV examiner offices. Development of specific policies regarding reporting should be vetted by legal counsel. Policies and laws can vary by state or provence.60 In states with voluntary reporting laws, we recommend formal referral to the DMV for refractory cases or for those patients deemed to be at a very high risk for a crash and/or injury.

Studies are needed to compare the benefits and costs of mandatory reporting to state DMVs with voluntary reporting. Although increased age is associated with a higher proportion of cognitively impaired drivers, mandatory age-based driver testing has not been shown to decrease crash rates.61 Decision analysis studies have not consistently revealed the benefits of systematically screening and evaluating demented drivers.62 Cleary, more studies are needed in this area of the benefits and risks of screening for cognitively impaired older adults.

Future research on assistive technologies, such as user-friendly global position system (GPS) devices may assist with geographic orientation. Crash warning systems need to be developed to maximize independent living for people with mild cognitive impairment. Preliminary data supports the beneficial effects of cholinesterase inhibitors on driving simulation tasks in demented individuals,63 as well as cognitive stimulation,64 and exercise interventions directed at driving-related cognitive abilities in older adults.65 Additional studies are needed on these types of interventions, their potential impact on cognitive domains, and their ability to prolong safe driving. As the baby boom generation comes of age there will be a pressing need to develop comprehensive alternative transportation systems for our older and cognitively impaired drivers.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Carr and Dr. Ott take entire responsibility and participated in the writing and creation of the entire manuscript. This includes conception and design, review of the literature and interpreting the current evidence. They both were involved in the initial draft and subsequent critical revisions. We thank Mr. and Mrs. W and Dr. D for graciously sharing their story with us.

Dr. Ott has received grant support from NIA as well as Pfizer, Wyeth, Elan, Jannsen, Johnson and Johnson, and Baxter pharmaceutical companies; he has been a paid consultant for Medivation and Forrest, and a paid speaker for Forrest.

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by the Washington University Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (P50AG05681, Morris PI), and the program project, Healthy Aging and Senile Dementia (P01AG03991, Morris J PI) and grant (AG16335, Ott B PI) from the National Institute on Aging.

Role of the Sponsor: The Care of the Aging Patient series is sponsored by The SCAN Foundation.

Web Resources on Dementia and Driving

Caregiver and Patient Resources

Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists (ADED)

The ADED Web page describes warning signs of driving with a link to the directory on locating a driving specialist.

http://www.driver-ed.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=104

American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA)

Information on occupational therapists and their role in driving assessment and rehabilitation.

http://www1.aota.org/olderdriver/

Alzheimer's Association

The national association's Web site on driving and dementia with links to educational information. Local chapter websites will often list available driving clinics in the area.

http://www.alz.org/safetycenter/we_can_help_safety_driving.asp

Family Caregiver Alliance

1) Fact sheet on Dementia and Driving

2) A review of the myriad of caregiver issues related to this topic.

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=432

3) Dementia and Driving and the California State Law

http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=433

Lennox and Addington Dementia Network

Dementia and Driving-Family and Caregiver Information.

http://www.providencecare.ca/objects/rte/File/Health_Professionals/drivinganddementia_patient.pdf

Caregiver site on when to stop driving.

http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/alzheimers/HO00046

National Association of Social Workers

Locate a social worker near you.

The Caregiver Project

Alzheimer's Disease, Dementia and Driving

This Web site catalogs and links to other topical Web sites.

http://www.quickbrochures.net/alzheimers/alzheimers-driving.htm

The Hartford

Insurance company Web site with links to the brochure, “At the Crossroads” and “We Need to Talk”

http://www.thehartford.com/alzheimers/

http://www.thehartford.com/talkwitholderdrivers/

WebMD

Dementia and Driving Video for caregivers.

Physician Resources

Alzheimer's Knowledge Exchange Web site

Selected links on dementia and driving

http://www.candrive.ca/en/resources/physician-resources/43-driving-and-dementia.html

American Family Physician

Dementia and Driving Handout for the Office

http://www.aafp.org/afp/20060315/1035ph.html

American Medical Association (AMA)

Physician's Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers

Dementia and Driving, p. 47

http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/chapter4.pdf

and State Licensing and Reporting Laws (last updated 2004)

http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/chapter8.pdf

California Department of Motor Vehicles

Discussion of the California Law and Dementia Severity

http://www.dmv.ca.gov/dl/driversafety/dementia.htm

Dementia and Driving Toolkit: The Dementia Network of Ottawa

A toolkit for clinicians that evaluation and counsel older drivers.

Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS)

An website on older driver laws for driver licensing that is updated every six months.

http://www.iihs.org/laws/olderdrivers.aspx

Neurology

When should patients with Alzheimer's stop driving by Deniz Erten-Lyons

NeuroPsychiatry

Driving with Dementia-What is the Physician's Role?

A discussion of the physician's role in this process.

http://www.neuropsychiatryreviews.com/may02/npr_may02_demdrivers.html

Psychiatry Weekly

Psychogeriatrics: Advanced Age, Dementia and Driving

A discussion of the physician role, ethics, and communication issues

http://www.psychiatryweekly.com/aspx/article/articledetail.aspx?articleid=984

SGIM Annual Meeting 2009

Driving Risk Assessment, p 17, 18, 19

A discussion and review of tools that may assist in assessing older drivers.

http://www.sgim.org/userfiles/file/WE03_Kao_Helen_201345.pdf

Talking to Seniors and Their Family about Dementia and Driving

Educational Pamphlet, by Mark Rappaport, 2007

VA Government Pamphlet

Dementia and Driving Handout

http://www1.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=1162

Transportation Alternatives

Agency on Aging

Assists in finding local resources for aging in the community.

American Public Transportation Association (APTA)

Locate a local transportation provider in your community.

http://www.publictransportation.org/systems/

American Administration on Aging (AOA)

Eldercare locator

Assists in finding older adult resources in your community.

Community Transportation Association (CTAA)

Information on transportation in the United States.

ITNAmerica

Novel older adult transportation system that provides 24-7 rides to seniors.

National Center on Senior Transportation

A Web site that provides links to many transportation agencies. Available summer of 2010, will be the Person-Centered Mobility Preparedness Inventory (PCMPI).

http://seniortransportation.easterseals.com/site/PageServer?pagename=NCST2_trans_care

Seniors on the MOVE

Assists older adults with relocation to another community.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Carr has support from the NIA, Missouri Department of Transportation Division of Highway Safety, as well as Elan and Jannsen; he has been a paid consultant for the American Medical Association Older Driver Project and ADEPT.

Other Sources: See website resources for more information.

References

- 1.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1133–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frittelli C, Borghetti D, Iudice G, et al. Effects of Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment on driving ability: a controlled clinical study by simulated driving test. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:232–238. doi: 10.1002/gps.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadley VG, Okonkwo O, Crowe M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and everyday function: an investigation of driving performance. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(2):87–94. doi: 10.1177/0891988708328215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foley DJ, Masaki K, Ross GW, White LR. Driving cessation in older men with incident dementia. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2000;48:928–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odenheimer GL. Dementia and the older driver. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 1993;9:349–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stutts JC, Stewart JR, Martell CM. Cognitive test performance and crash risk in older driver population. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 1998;30:337–346. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(97)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, Shaheen E. Evaluating driving performance of cognitively impaired and healthy older adults: a pilot study comparing on-road testing and driving simulation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1309–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox DJ, Quillian WC, Thorndike FP, et al. Evaluating driving performance of outpatients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:264–71. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.11.4.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzo M, McGehee DV, Dawson JD, Anderson SN. Simulated car crashes at intersections in drivers with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:10–20. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt LA, Murphy CF, Carr D, Duchek JM, Buckles V, Morris JC. Reliability of the Washington University Road Test. A performance-based assessment for drivers with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:707–12. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550180029008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott BR, Heindel WC, Papandonatos GD, et al. A longitudinal study of drivers with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1171–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000294469.27156.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson JD, Anderson SW, Uc EY, et al. Predictors of driving safety in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72:521–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341931.35870.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grace J, Amick MM, D'Abreu A, et al. Neuropsychological deficits associated with driving performance in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11:766–75. doi: 10.1017/S1355617705050848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uc EY, Rizzo M, Anderson SW, et al. Driver route-following and safety errors in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004;63:832–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000139301.01177.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duchek JM, Carr DB, Hunt L, et al. Longitudinal Driving Performance in Early Stage Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. JAGS. 2003;51:1342–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitten LJ, Perryman KM, Wilkinson CJ, et al. Alzheimer and vascular dementias and driving. A prospective road and laboratory study. JAMA. 1995;273:1360–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Simone V, Kaplan L, Patronas N, et al. Driving abilities in frontotemporal dementia patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000096317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkinson MA, Berg-Weger ML, Carr DB, et al. Driving and Dementia of the Alzheimer Type: Beliefs and Cessation Strategies Among Stakeholders. The Gerontologist. 2005;45:675–685. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ott BR, Anthony D, Papandonatos GD, et al. Clinician assessment of the driving competence of patients with dementia. JAGS. 2005;53:829–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubinsky RM, Stein AC, Lyons K. Practice parameter: risk of driving and Alzheimer's disease (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;54:2205–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.12.2205. 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott BR, Heindel WC, Whelihan WM, Caron MD, Piatt AL, Noto RB. A single-photon emission computed tomography imaging study of driving impairment in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Dement.Geriatr.Cogn Disord. 2000;11(3):153–160. doi: 10.1159/000017229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berndt A, Clark M, May E. Dementia severity and on-road assessment: briefly revisited. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2008;27:157–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobbs BM. (NHTSA Publication: DTNH22-94-G-05297).Medical Conditions and Driving: Current Knowledge, Final Report Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlton J, Koppel S, O'Hare M, et al. Influence of chronic illness on crash involvement of motor vehicle drivers, Monash University Accident Research Centre. 2004 Report No. 213. Supported by Swedish National Road Administration. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Association AMA Physician's Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers. 2003:33–38. Chapter 3: Formally Assess Function. Available at; http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/chapter9.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2009.

- 28.Wang C, Carr D. Older Driver Safety: A Report from the Older Drivers Project. JAGS. 2004;52:143–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lococo Kathy, Tyree Renee. Medication Impaired Related Driving. 2008 Available at; https://webapp.walgreens.com/cePharmacy/viewpdf?fileName=transportation_tech.pdf. Accessed on September 14, 2009.

- 30.Hunt L, Morris JC, Edwards D, Wilson BS. Driving performance in persons with mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:747–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb07465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croston J, Meuser TM, Berg-Weger M, Grant B, Carr DB. Driving Cessation in Older Adults with Dementia. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2009;25:154–162. doi: 10.1097/TGR.0b013e3181a103fd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lesikar SE, Gallo JJ, Rebok GW, Keyl PM. Prospective study of brief neuropsychological measures to assess crash risk in older primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:11–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molnar FJ, Patel A, Marshall SC, et al. Clinical utility of office-based cognitive predictors of fitness to drive in persons with dementia: A systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1809–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reger MA, Welsh RK, Watson GS, et al. The relationship between neuropsychological functioning and driving ability in dementia: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:85–93. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whelihan WM, DiCarlo MA, Paul RH. The relationship of neuropsychological functioning to driving competence in older persons with early cognitive decline. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;20:217–28. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ott BR, Festa EK, Amick MM, Grace J, Davis JD, Heindel WC. Computerized maze navigation and on-road performance by drivers with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21:18–25. doi: 10.1177/0891988707311031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarthy DP, Mann WC. Sensitivity and Specificity of the American Medical Association's Assessment of Driving Related Skills (ADReS) Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2006;22:139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ball KK, Roenker DL, Wadley VG, et al. Can High-Risk Older Drivers Be Identified Through Performance-Based Measures in a Department of Motor Vehicles Setting? JAGS. 2005;54:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meuser TM, Carr DB, Berg-Weger M, et al. Driving and Dementia in Older Adults: Implementation and Evaluation of a Continuing Education Project. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:680–687. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staplin L, Gish KW, Wagner EK. MaryPODS revisited: Updated crash analysis and implications for screening program implementation. Journal of Safety Research. 2003;34:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedard M, Weaver B, Darzins P, Porter M. Predicting Performance in Older Adults: We are Not There Yet! Traffic Injury Prevention. 2008;4:336–341. doi: 10.1080/15389580802117184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bedard M, Molloy DW, Lever JA. Factors associated with motor vehicle crashes in cognitively impaired older adults. Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders. 1998;12:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nasvadi GC, Wister A. Do Restricted Driver's Licenses Lower Crash Risk Among Older Drivers? A Survival Analysis of Insurance Data From British Columbia. The Gerontologist. 2009;49:474–484. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Byszewski AM, Graham ID, Amos S, et al. A continuing medical education initiative for Canadian primary care physicians: The driving and dementia toolkit: A pre- and post-evaluation of knowledge, confidence gained, and satisfaction. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1484–1489. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stav W, Hunt L, Arbesman M. Driving and Community Mobility for Older Adults: Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines. AOTA; Bethesda, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Korner-Bitensky N, Bitensky J, Sofer S, et al. Driving evaluation practices of clinicians working in the US and Canada. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;60:428–43. doi: 10.5014/ajot.60.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uc EY, Rizzo M. Driving and neurodegenerative diseases. Current Neurology & Neuroscience Reports. 2008;8:377–83. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin AJ, Marottoli R, O'Neill D. Driving assessment for maintaining mobility and safety in drivers with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009:CD006222. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006222.pub2. vol./is. /1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mezuk B, Rebok GW. Social integration and social support among older adults following driving cessation. J Gerontol Series B Psychol Sci Social Sci. 2008;63:S298–303. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.s298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marottoli RA, de Leon CFM, Glass TA, et al. Consequences of driving cessation: decreased out-of-home activity levels. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55:S334–340. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.s334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor BD, Tripodes S. The effects of driving cessation on the elderly with dementia and their caregivers. Accid Anal Prev. 2001;33:519–28. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(00)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol. 2001;56(6):S343–351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol. 2001;56(6):S343–351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freeman EE, Gange SJ, Munoz B, Wet SK. Driving status and risk of entry into long-term care in older adults. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1254–1259. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silverstein N. When Life Exceeds Safe Driving expectancy: Implications for Gerontology and Geriatrics Education. 2008;29:305–309. doi: 10.1080/02701960802497795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kelly R, Warke T, Steele I. Medical restrictions to driving: the awareness of patients and doctors. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:537–539. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.887.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rapoport MJ, Herrmann N, Molnar FJ, et al. Sharing the Responsibility for assessing the risks of the driver with dementia. CMAJ. 2007;177:600–602. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meuser T, Carr DB, Ulfarsson GF. Motor-Vehicle Crash History and Licensing Outcomes for Older Drivers Reported as Medically Impaired in Missouri Accident Analysis & Prevention. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2009;41:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 2.24. Impaired drivers and their physicians. Adopted December 1999, Available at; http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion224.shtml. Accessed on; September 14, 2009.

- 60.Rapoport M, Herrman N, Molnar F, et al. Sharing the responsibility for assessing the risk of the driver with dementia. CMAJ. 177:599–601. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langford D, Bohensky M, Koppel S, Newstead S. Do age-based mandatory assessments reduce older drivers' risk to other road users? Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2008;40:1913–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leproust S, Lagarde E, Salmi LR. Risks and Advantages of Detecting Individuals Unfit to Drive: A Markov Decision Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1796–803. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0777-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Daiello LA, Ott BR, Festa EK, Heindel WC. Effects of cholinesterase inhibitors on visual attention in drivers with Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychopharmacology. 2010 June;30(3) doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181da5406. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edwards JD, Wadley VG, Vance DE, Wood, et al. The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday performance. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:262–271. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331336788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marmeleiraa JF, Godinhob MB, Fernadesa OM. The effects of an exercise program on several abilities associated with driving performance in older adults. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2009;41:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dubinsky RM, Williamson A, Gray CS, Glatt SL. Driving in Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1112–1116. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carr DB, Duchek J, Morris JC. Characteristics of motor vehicle crashes of drivers with dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fitten LJ, Perryman KM, Wilkinson CJ, et al. Alzheimer and vascular dementias and driving. A prospective road and laboratory study. JAMA. 1995;273:1360–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tuokko H, Tallman K, Beattie BL, Cooper P, Weir J. An examination of driving records in a dementia clinic. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995;50:S173–S181. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.3.s173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Trobe JD, Waller PF, Cook-Flannagan CA, Teshima SM, Bieliauskas LA. Crashes and violations among drivers with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:411–416. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550050033021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drachman DA, Swearer JM. Driving and Alzheimer's disease: the risk of crashes. Neurology. 1993;43:2448–2456. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.12.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Friedland RP, Koss E, Kumar A, et al. Motor Vehicle Crashes in dementia of the Alzheimer's Type. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:782–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zuin D, Ortiz H, Boromai D, Lopez LZ. Motor vehicle crashes and abnormal driving behaviors in participants with dementia in Mendoza, Argentina. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:29–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Johansson K, Lundberg C. The 1994 International Consensus Conference on Dementia and Driving: a brief report. Swedish National Road Administration. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 1):62–9. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199706001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias of late life. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(5 Suppl):1–39. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer's Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA. 1997;278:1363–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Patterson CJ, Gauthier S, Bergman H, et al. Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia: a physician's guide to using the recommendations. CMAJ. 1999;160:1738–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dobbs BM, Carr D, Eberhard J, et al. Determining medical fitness to drive: guidelines for physicians. American Association of Automotive Medicine/National Highway Transportation Safety Association Consensus Meeting Guidelines; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alzheimer's Association . Position statement: Driving and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Association; 2001. Available at: http://www.alz.org/national/documents/statements_driving.pdf. Accessed on September 14, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 80.American Medical Association AMA Physician's Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers. 2003:160. Available at; http://www.amaassn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/chapter9.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2009.

- 81.Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:561–72. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Canadian Medical Association . Determining medical fitness to operate motor vehicles: CMA driver's guide. 7th ed ed. The Association; Ottawa: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ott BR, Festa EK, Amick MM, Grace J, Davis JD, Heindel WC. Computerized maze navigation and on-road performance by drivers with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21:18–25. doi: 10.1177/0891988707311031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Snellgrove CA. Cognitive screening for the safe driving competence of older people with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia. AustralianTransport Safety Bureau; Canberra: 2005. 8-25-2009. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brown LB, Stern RA, Cahn-Weiner DA, et al. Driving Scenes test of the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (NAB) and on-road driving performance in aging and very mild dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;20:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lincoln NB, Taylor JL, Vella K, Bouman WP, Radford KA. A prospective study of cognitive tests to predict performance on a standardised road test in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1002/gps.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]