Abstract

Background

When the German national medical licensing regulations were changed in 2002, the second part of the medical licensing examination was supplemented with a practical component and expanded from one day to two. The aim of this study was to assess the written and oral-practical examination grades before and after the licensing reform.

Methods

We compared the results that were obtained on the oral and written components of the second part of the national medical licensing examination under the old and new regulations (M2o and M2n, respectively) by a total of 2056 students at the Technical University (TUM) and Ludwig-Maximilian University (LMU) medical schools, both in Munich, from the spring of 2004 to the spring of 2008. We assessed the grades themselves as well as the correlation between the grades on the oral and written components before and after the reform.

Results

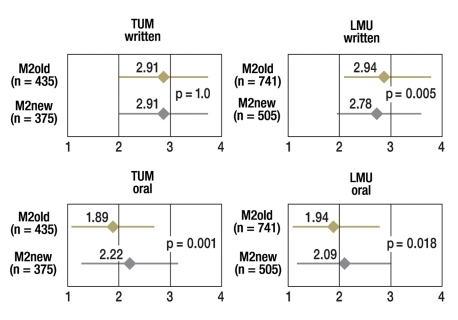

Grades on the written component of the examination did not differ to any statistically significant extent before and after the reform (TUM: M2o 2.91±0.92, M2n 2.91±0.87. LMU: M2o 2.94±0.85, M2n 2.78±0.873). There was, however, a significant change in the oral examination grades (TUM: M2o 1.89±0.81, M2n 2.22±0.96; p<0.001. LMU: M2o 1.94±0.86, M2n 2.09±0.93, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Additional analysis of the grades obtained before and after the reform reveals a significantly increased concordance between grades on the oral and written components of the examination.

On June 27, 2002 the new German national medical licensing regulations (ÄAppO) took effect. Among other things, they reformed the second part of the medical licensing examination (Staatsexamen) (M2). A significant change concerned the time and the scope of the written examination: The first part and the written part of the second medical licensing examination (“first medical licensing examination” after the 3rd year of study; “second medical licensing examination” before the beginning of the practical year) were eliminated in favor of a written examination after completion of the practical year (PJ—a pregraduate internship). Accordingly the subject matter to be covered in the second part of the new medical licensing examination (M2n)—the so-called jawbreaker examination—includes the content of the entire clinical phase of medical education after the first part of the medical licensing examination (“Physikum” = preclinical medicine) including the practical year (PJ), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Depiction of the examination components before and after the changed ÄAppO in 2002; *M2n includes the “jawbreaker” examination and an oral-practical examination in a new format;

M2o, old ÄAppO; M2n, new ÄAppO

The format of the oral examination components was also changed. In addition to the oral examination day which continues unchanged from the old medical licensing regulations, a second examination day is added on which a practical examination with patients occurs (§30 Par. 1 ÄAppO) (1). In this regard the ÄAppO requires that: “The candidate must show in a case-related manner that he/she knows how to apply the knowledge obtained during his/her studies in the practice of medicine and that he/she possesses the interdisciplinary basic knowledge and the necessary skills and abilities” (§28 Par. 2 ÄAppO) (1). This additional examination day is used by the new ÄAppO to evaluate the results-oriented objective formulated in §1: The “physician who is scientifically and practically trained in medicine is able to autonomously and independently practice the medical profession”. The examination conducted at the bedside facilitates an evaluation that goes beyond mere cognitive-theoretical information and additionally assesses the clinical-practical abilities and skills of future physicians in light of the above-named educational objective. This evaluates a physician’s behavior when interacting with patients, the ability of the future physician to present a case in a structured manner, and practical abilities such as examination procedures (2). However, the ÄAppO does not specify a standardized procedure for conducting the oral-practical examination which means that grading of the oral-practical examination is less objective and reliable than the evaluation of the written examination (3). Readily accessible data of the Institute for Medical and Pharmaceutical Test Questions (Institut für medizinische und pharmazeutische Prüfungsfragen, IMPP) concerning the correlation of the written and oral medical licensing examination results are unavailable. However, sensibly, reliably and objectively evaluating the clinical competency of future physicians in the manner specified by the ÄAppO requires a standardized testing procedure with clinically oriented testing modalities (4).

The present investigation is an explorative study to describe the convergence or divergence of the oral and written partial grades achieved in the medical licensing examination after the ÄAppO was changed in 2002. This should serve as the basis for further development of the testing modalities to achieve a better standardized oral-practical examination.

Methods

We evaluated the examination grades of 810 students at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and 1246 students at the Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich (LMU) who completed the second part of the medical licensing examination between 2004 and 2008.

At both universities no training was provided to those whose duty it is to administer and/or evaluate the tests and no internal structuring by the faculty was undertaken for the implementation of the oral or the oral-practical part of the second medical licensing examination. The clinical program of study at the two universities differs with regard to the teaching methods employed, the degree of subject matter integration, and the examinations administered by the medical faculties.

The basis for evaluating the M2o (old ÄAppO) were the grades achieved by all students who completed the second part of the medical licensing examination between Spring 2004 and Spring 2005 (three exams with a total of 1176 candidates) and the basis for evaluating the M2n (new ÄAppO) were the grades achieved between Fall 2006 and Spring 2008 (four examinations with a total of 880 candidates).The examinations of Fall 2005 and Spring 2006 were excluded since these were the last examinations before and the first examinations after the change to the new examination rules. This was done to reduce any distorting effects caused by students who elected to take the examination earlier than usual and those who had postponed taking the examination at the usual time.

The grade earned in the oral-practical part of the examination is calculated on the basis of two partial grades: The first partial grade describes the performance in the clinical-practical part of the examination at the bedside of a patient on the first day; the second partial grade describes the performance in the oral examination on the second day. In contrast to the grade earned on the written part of the examination (which was unavailable to the examiners), the individual grades for the two days of the oral-practical part are awarded simultaneously and thus a separate evaluation of these partial grades does not seem sensible. Therefore, in what follows below the expression “oral exam grade” refers to the overall grade earned in the oral-practical part of the examination. The Examining Authority for the Implementation of Examinations According to the Medical Licensing Regulations as Ordered by the Government of Upper Bavaria provided the authors with all of the individual grades in anonymized form.

We calculated the average grades achieved on the written part and the oral part of M2o and M2n as well as the average difference of the written and oral grade of the M2o and M2n separately for both universities (TUM and LMU). We also performed a separate analysis for the two universities to detect statistical random events that could be the result of faculty-specific peculiarities. Furthermore, we calculated which proportion of the candidates before and after the ÄAppO was changed achieved the same grade in the written and oral part of the second medical licensing examination, namely as a function of the written grade.

In each case we statistically compared the examination results before and after the ÄAppO was changed (M2o versus M2n). The examination grades were based on an interval scale to facilitate an easier depiction of the average grades and the difference of the grades as the mean ± standard deviation, although strictly seen examination grades should be considered on an ordinal scale. Differences between the examination groups were evaluated for statistical significance by means of ANOVA and post hoc testing (Bonferroni). Only the p-values are specified that describe the comparison before and after the ÄAppO was changed (M2o versus M2n).

Results

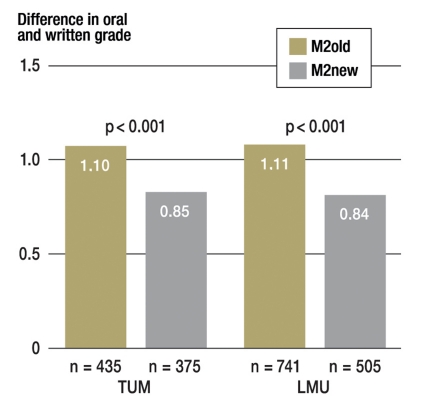

At the TUM the average written examination grades did not change after introduction of the new examination rules (M2o: 2.91 ± 0.92; M2n: 2.91 ± 0.87; p = 1.000), while there was a slight improvement in the written examination grades at the LMU (M2o: 2.94 ± 0.85; M2n: 2.78 ± 0.84; p = 0.005). The oral examination grades changed more clearly at both universities. At the TUM the oral examination grade changed from 1.89 ± 0.81 to 2.22 ± 0.96 (p<0.001) and at the LMU from 1.94 ± 0.86 to 2.09 ± 0.93 (p = 0.018) (figure 2). It is notable that the average individual difference of the written and the oral grade at both universities decreased to the same degree as a result of the introduction of the new examination rules. While M2o still exhibited an average difference of the written and the oral grade of 1.02 ± 0.94 (TUM) and 1.01 ± 0.92 (LMU), the new examination rules only yielded an average difference of 0.70 ± 0.89 (TUM) and 0.69 ± 0.90 (LMU) (p<0.001 for both universities) (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Written and oral partial grades in the second medical licensing examination (Staatsexamen) before and after the changed ÄAppO in 2002

Figure 3.

Difference of the oral and written partial grades in the second medical licensing examination (Staatsexamen) before and after the changed ÄAppO in 2002

In a second step we compared the individual oral examination grades with the corresponding written examination grades to clarify whether the decrease in the average difference of the written and the oral grade as a result of the new examination rules only resulted in an approximation of the average values or in a changed grade distribution with greater or, as applicable, lesser agreement of the individual grades. By taking the proportion of students who achieved equivalent grades in the written and oral part of the examination as a measure of this, it is noteworthy that this proportion in fact increased at both universities from 25% to 35% (TUM) and correspondingly from 22% to 35% (LMU). It is interesting to ask which students exhibited a greater agreement of these grades. Figure 4 shows the proportion of students with identical grades in the written and oral part as a function of the written grade. In the group of students with a “good” written examination grade the proportion of candidates with identical grades hardly changed at all at both universities (TUM–M2o: 45%; TUM–M2n: 44%; LMU–M2o: 43%; LMU–M2n: 46%). In the group of students with a grade of “satisfactory” or “sufficient” on the written part of the examination, the proportion of candidates with identical grades doubled at both universities (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proportion of students with identical grades as a function of the grade in the written component before and after the changed ÄAppO in 2002

In the small group of students who failed the written part of the examination (TUM–M2o: 3.4%; TUM–M2n: 4.5%; LMU–M2o: 2.8%; LMU–M2n: 2.6 percent) there was a comparable trend of greater correspondence between the oral-practical grade and the written grade after the ÄAppO was changed. Before the ÄAppO was changed, only 14% of the students failing the written part also achieved an insufficient grade in the oral examination; after the ÄAppO was changed, this proportion increased to 36%.

Discussion

The change in the German national medical licensing regulations has altered the format, scope, and time of administration of the medical licensing examinations. The written examination of the second part (M2) now includes all of the subject matter encountered during the clinical phase of medical education as well as the information to be mastered during the practical year (PJ). Furthermore, the entire examination—both the written and the expanded oral-practical component—were placed at the end of the program of study after completion of the practical year (PJ). Only recently have the stresses and possible consequences of this examination (called the “jawbreaker” exam by students) been reported (5). While changes of the written component affected the format, scope, and the time of administering the examination, the modality of the oral part of the examination also was fundamentally changed. In contrast to the old ÄAppO, a clinical-practical examination must be conducted on the first day, which according to the ÄAppO “should practically evaluate the knowledge acquired during the study of medicine in a case-related manner” (1, 2). The practical abilities and skills of the future physician which are to be evaluated must—in contrast to theoretical knowledge—be evaluated in a more comprehensive manner. Without a structured and standardized examination procedure, such an oral-practical examination is less objective, reliable, and thus less valid than written examinations (3). For example, only a minimal correlation could be detected between the results in the written and oral parts of the preclinical (Physikum) component of the medical licensing examination (6). The fundamental question arises to what extent knowledge that is examined in writing is the prerequisite for a successful performance on the clinical-practical part of the examination or to what extent both examination components evaluate independent aspects of medical competency. Assuming that the written and the clinical-practical part of the examination test different abilities of the students, the partial grades would be expected to diverge more strongly. Thus, the new part of the second medical licensing examination provides the means of evaluating medical skills and abilities that were not taken into consideration by the examination format of the old ÄAppO. Therefore, the present study has focused on the task of comparing the grades obtained before and after the changes implemented to the ÄAppO. It was of special interest to see whether the changes in the ÄAppO led to a weaker or a stronger grade divergence between the written and oral-practical partial grades.

To this purpose, the grades from a total of 2056 students at two Bavarian universities (TUM and LMU) were examined before and after the changed ÄAppO. While the average grade on the written component did not change or changed only slightly after introduction of the new ÄAppO, it was possible to observe a notably higher concordance of the grades obtained in the oral and written parts of the examination at both universities. This higher concordance between the written and oral partial grades was especially seen in candidates with a below average level of performance and was the result of grading the individual students more strictly in the oral-practical part of the M2n.

There are several possible explanations for the stricter grading in the oral-practical part of the M2n and the associated greater concordance of the partial grades. First, it is possible that the examiners in the oral-practical examination after the ÄAppO was changed expected more from the students since this was now a final examination which also evaluated abilities that should have been acquired during the recently completed practical year (PJ). Second, after the ÄAppO was changed, it could have been more difficult for the candidates to prepare for the new format and the content of the oral-practical examination (unavailability of examination protocols, unknown examination format) which especially would explain the difference in students with a below average performance. However, expressed fears that the “jawbreaker examination” would lead to a deterioration of the partial grades on the written examination have not been confirmed.

Apart from the examination modalities, additional factors have changed that could have an effect on the result of the medical licensing examination following the introduction of the new ÄAppO. However, if one assumes that medical licensing ensures the competency level of a physician who is capable of undergoing postgraduate training, it follows that valid examinations are required for all necessary competencies which also include a series of practical abilities (7). A national competency-based catalog of learning objectives, which operationalizes all of these competencies and extends beyond the subject matter catalog used for the second medical licensing examination (catalog 2), is missing in Germany while a series of European countries have implemented this (8, 9). Such a national catalog of learning objectives is the prerequisite for operationalizing the examination objectives of the oral and clinical-practical part of the M2n (10). Through more structuring and a greater number of independent observations of this examination component—using the USA as an example (11), there is a future possibility of designing this part of the examination to be more reliable and meaningful than before without increasing the time demands on individual examiners at the faculties of medicine (12). On the other hand, this requires a time-consuming preparation of standardized examination materials and evaluation criteria which is unavoidably associated with coordination across several faculties to economize this process.

Limitation of the study: This is an investigation that was conducted at only two German universities. Collecting the pertinent data on a national basis throughout Germany and including all universities is desirable and can be realized in cooperation with the State Examination Authorities and the IMPP. An additional limitation concerns the different factors that could have exerted a varying effect on the examination grades after the ÄAppO was changed and which cannot be evaluated independently by the present study. A third limitation is the unstructured examination situation in the oral-practical examination. Only a structured examination situation would facilitate a qualified comparison between universities over a longer period of time. Such an undertaking is planned in Switzerland for 2011 with the national introduction of a structured oral examination (13, 14).

Key Messages.

The new medical licensing regulations for 2002 caused significant changes in the format of the German medical licensing examination (Staatsexamen). Among other changes, an additional examination day with a clinical examination at the bedside of a patient was introduced.

Compared to the examination situation before the medical licensing regulations were changed, the written part of the medical licensing examination which now include a significantly larger amount of material to be mastered did not result in a deterioration of the examination grades.

In contrast to the written partial grades, the oral partial grades changed significantly.

In the examination situation after introduction of the new medical licensing regulations, the authors were able to detect a significantly greater concordance between the written and oral partial grades.

To achieve comparable examination situations on a national basis, standardized examination methods (e.g., OSCE) and national catalogs of learning objectives should be defined in the future.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by mt-g

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that a conflict of interest as defined in the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors does not exist.

References

- 1.Ärztliche Approbationsordnung (ÄAppO) in der Fassung vom 27. 6. 2002. Bundesgesetzblatt. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinweise für die Vorbereitung und Durchführung des mündlich-praktischen Teils des zweiten Abschnitts der Ärztlichen Prüfung nach der Approbationsordnung für Ärzte vom 27. Juni 2002 (ÄAppO) Regierung von Oberbayern. 2007. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Möltner A, Schellberg D, Jünger J. Grundlegende quantitative Analysen medizinischer Prüfungen. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2006;23 Doc53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howley LD. Performance assessment in medical education: Where we’ve been and where we’re going. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27:285–303. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meißner M. Zwei Jahre „Hammerexamen“: Ruhe nach dem Sturm. Dtsch Arztebl. 2009;106(4) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bussche Hvd, Wegscheider K, Zimmermann T. Der Ausbildungserfolg im Vergleich (III) Dtsch Arztebl. 2006;103:A 3170–A 3176. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuwirth LWT, Vleuten CPMvd. Changing education, changing assessment, changing research? Medical Education. 2004;38:805–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Scottish Doctor Project. www.scottishdoctor.org.

- 9.Bürgi H, Rindlisbacher B, Bader C, et al. Swiss Catalogue of Learning Objectives for Undergraduate Medical Training - June 2008 Working Group under a Mandate of the Joint Commission of the Swiss Medical Schools. www.sclo.smifk.ch.

- 10.Schuwirth L. The need for national licensing examinations. Medical Education. 2007;41:1022–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadakis MA. The step 2 clinical-skills examination. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1703–1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wass V, Wakeford R, Neighbour R, Vleuten CVd. Achieving acceptable reliability in oral examinations: an analysis of the Royal College of General Practitioners membership examination’s oral component. Medical Education. 2003;37:126–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hottinger U, Krebs R, Hofer R, Feller S, Bloch R. Strukturierte mündliche Prüfung für die ärztliche Schlussprüfung - Entwicklung und Erprobung im Rahmen eines Pilotprojekts. Analysebericht des Instituts für Medizinische Lehre. Universität Bern, Schweiz. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vu N, Baroffio A, Huber P, Layat C, Gerbase M, Nendaz M. Assessing clinical competence. A pilot project to evaluate the feasibility of a standardised patient-based practical examination as a component of the Swiss certification process. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:392–399. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]