Abstract

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) is the ligand-activated transcription factor responsible for mediating the toxicological effects of dioxin and xenobiotic metabolism. However, recent evidence has implicated the AHR in additional, nonmetabolic physiological processes, including immune regulation. Certain tumor cells are largely nonresponsive to cytokine-mediated induction of the pro-survival cytokine interleukin (IL) 6. We have demonstrated that multiple nonresponsive tumor lines are able to undergo synergistic induction of IL6 following combinatorial treatment with IL1β and the AHR agonist 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Such data implicate the AHR in tumor expansion, although the mechanistic basis for the AHR-dependent synergistic induction of IL6 has not been determined. Here, we demonstrate that ligand-activated AHR is involved in priming the IL6 promoter through binding to nonconsensus dioxin response elements located upstream of the IL6 start site. Such binding appears to render the promoter more permissive to IL1β-induced binding of NF-κB components. The nature of the AHR-dependent increases in IL6 promoter transcriptional potential has been shown to involve a reorganization of repressive complexes as exemplified by the presence of HDAC1 and HDAC3. Dismissal of these HDACs correlates with post-translational modifications of promoter-bound NF-κB components in a time-dependent manner. Thus the AHR plays a role in derepressing the IL6 promoter, leading to synergistic IL6 expression in the presence of inflammatory signals. These observations may explain the association between enhanced expression of AHR and tumor aggressiveness. It is likely that AHR-mediated priming is not restricted to the IL6 promoter and may contribute to the expression of a variety of genes, which do not have consensus dioxin response elements.

Keywords: Histone Deacetylase, Interleukin, NF-κB, Transcription Co-activators, Transcription Repressor, AHR, IL6, Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor

Introduction

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR)2 is a ligand-activated transcription factor of the basic helix-loop-helix, Per-Arnt-Sim class of proteins, historically studied as a mediator of xenobiotic response and metabolism. The AHR-mediated signaling pathway has been documented extensively, as exemplified in the review by Beischlag et al. (1). Residing in the cytoplasm prior to activation, the AHR is complexed with a dimer of hsp90 and XAP2. The AHR binds an agonist, which induces translocation to the nucleus, followed by release of its chaperones and subsequent heterodimerization with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT). This heterodimer exhibits an ability to bind dioxin response elements (DREs) at the promoters of target genes and plays a role in transcription. The most common ligand studied that mediates AHR activation is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), although it binds a variety of xenobiotics including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons such as benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are common environmental pollutants that result from car exhaust, manufacturing, iron foundries, cigarette smoke, etc. As a xenobiotic receptor, activated AHR binds to DREs in the promoters of cytochrome P4501A genes, which express enzymes that act in phase I drug metabolism. However, the AHR has recently been shown to have numerous physiological roles aside from drug metabolism. Such endogenous activities include differentiation of Th17 immune cells, regulation of acute phase response genes, antiestrogenic activities, and modulation of NF-κB protein activity (2–5). These activities occur through DRE binding, as well as through protein-protein interactions.

We have previously shown that, in both the human MCF-7 breast cancer cell line and the ECC1 endocervical cancer cell line, IL6 production is synergistically increased following concomitant exposure to an AHR ligand and pro-inflammatory IL1β (6). The low level of AHR activation needed to mediate this response, combined with the fact that increased IL6 protein secretion continued for 72 h after the initial dose of ligand, points to a potentially low threshold that cancer cells must pass before producing and releasing extensive amounts of a known pro-growth signal. Furthermore, release of IL6 from tumor cells can lead to an autocrine loop that enhances other inflammatory and anti-apoptotic signaling pathways. IL6 is an NF-κB-regulated gene; thus our initial findings verified that the p65 (RELA) subunit was involved in the synergistic increase. However, a more detailed transcriptional mechanism was not fully explored. Elucidating the means by which IL6 is synergistically activated by the AHR in MCF-7 cells has the potential to provide insight useful in other tissue and tumor situations. MCF-7 cells express low basal and low IL1β-induced levels of IL6 expression, but this is not the case for all cell lines (7). It has been postulated that the lack of IL6 inducibility in MCF-7 cells is due to the presence of co-repressors and a closed chromatin structure at the promoter (8). An understanding of how the AHR can derepress this gene is important because of the pleiotropic nature of IL6 in the tumor microenvironment. For example, numerous carcinomas have shown pro-growth, anti-apoptotic, and pro-invasive abilities upon exposure to increased IL6 levels (9–14).

The observation that NF-κB signaling is involved in both oncogenic and immune pathways has led to numerous reviews on the functional role of prominent family members (e.g. p65, RELB) and, to a lesser extent, other related family members such as IκBζ (15, 16). There are a number of pathways by which the NF-κB family of proteins are regulated that can lead to transcriptional activation, the most prevalent being the canonical pathway. In this cascade of events, the p50 and p65 family members are sequestered in the cytoplasm by IκBα. Activating signals, including IL1β receptor signaling, lead to IKKα and IKKβ phosphorylating IκBα and dismissing it from the complex. This allows for nuclear localization of the p50-p65 heterodimer, which then binds to κB response elements in target gene promoters. Several tangential events also take place to maximize NF-κB activity, including acetylation of various p65 residues that enhance DNA binding and increase transcriptional activity (reviewed in Ref. 17). Nuclear IKKα can phosphorylate histones as well as neighboring transcription factors, and members of the IκB family have been shown to act as both repressors and activators when recruited to this DNA-bound complex (18, 19). The fact that NF-κB is intricately involved in cytokine regulation pointed to the REL family of proteins as likely targets for further study to uncover their role in AHR-mediated synergistic induction of IL6.

Upon discovering that AHR activation leads to greatly increased IL6 production in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, we then set out to investigate the mechanism by which this event occurs. The results revealed that activated AHR can bind imperfect DREs upstream of the IL6 promoter, leading to a regulatory region primed for NF-κB-mediated induction. The relative lack of IL6 induction in these cells following IL1β signaling alone appears to be due to the presence of co-repressors at the promoter, which is alleviated by the binding of AHR to its cognate response elements. Furthermore, AHR recruitment to the IL6 promoter results in a loss of HDAC1 occupancy, which coincides with an increase in acetylated p65 levels, a hallmark of optimal NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

MCF-7 breast tumor cells were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in a high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma), supplemented with 7% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories), 1,000 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Sigma). CV-1 cells were maintained in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin under identical incubation conditions.

Constructs

pGL3-promoter vector was subjected to digest with the restriction enzymes SacI and XhoI and subsequently ligated with sequences containing appropriate restriction sites. First, the pGL3–3.0kb vector was made by amplifying a 255-bp sequence spanning the region from −2897 to −3152 of the IL6 promoter with the primers 5′-TCACGCCTGTAAACCCAGCACTTT-3′ and 5′-GCGGTTGAAGTGAGCCAAGATCAT-3′. Second, the pGL3–3.0kb.synth vector was made by designing forward and reverse complimentary oligonucleotides containing three copies of a 15-base pair stretch of the IL6 promoter centered on the nonconsensus DRE found at −3050 bp. These sequences were 5′-GAGGCGCGTGGATCAGAGGCGCGTGGATCAGAGGCGCGTGGATCA-3′ and 5′-TGATCCACGCGCCTCTGATCCACGCGCCTCTGATCCACGCGCCTC-3′ (produced by Integrated DNA Technologies). Both inserts contained the appropriate restriction enzyme digest sites and were ligated into the pGL3-promoter vector. Vectors with insert were sequenced to verify PCR amplification fidelity or synthesis.

A synthetic, codon-optimized cDNA sequence encoding the wild-type human AHR (produced by GenScript) was inserted into pcDNA3 vector to create pcDNA3-AHR. This same sequence was modified to create the human AHR-GS DNA-binding mutant. Construction and characterization of the AHR-GS DNA-binding mutant is outlined in the supplemental text. This modified sequence was inserted into the vector to create pcDNA3-AHR-GS.

Gene Expression

MCF-7 cells were serum-starved 18 h before treatment. Treatment of cells was performed by diluting compounds to the desired working concentration in serum-free medium supplemented with 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. Total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRI reagent (Sigma) as specified by the manufacturer. The ABI high capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems) was used to prepare cDNA from isolated RNA. mRNA expression for all samples was measured by quantitative real time PCR using the Quanta SYBR Green kit on an iCycler DNA engine equipped with the MyiQ single color real time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The expressed quantities of mRNA were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels and plotted using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software). Histograms are plotted as the mean values of biological replicates, and the error bars represent the standard deviation of replicates. Real time primers used are listed in the supplemental text.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared by lysing cells in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm EGTA, 140 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with 1% Nonidet P-40, 300 mm NaCl, and protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Homogenates were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the soluble fraction was collected as whole cell extract. Protein concentrations were determined using the detergent-compatible DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Protein samples were resolved by Tricine-SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Primary antibodies used to detect specific proteins are shown in the supplemental text and were visualized using biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) in conjunction with [125I]streptavidin (Amersham Biosciences).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays

MCF-7 cells were grown to ∼90% confluency in 150-cm2 dishes and serum-starved 18 h before treatment. The cells were treated in serum-free medium supplemented with 5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin by diluting compounds to the desired working concentration for specified time. Following treatment, the cells were washed once with warm PBS, and chromatin complexes were chemically cross-linked using a 1% formaldehyde/PBS solution (final concentration) for 10 min at room temperature. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of glycine solution to a final concentration of 0.125 m; the cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS and collected in 2 ml of harvest buffer (100 mm Tris, pH 8.3, 10 mm dithiothreitol). The cells were centrifuged, washed in ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in 600 μl of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 10 mm EDTA). Chromatin was sheared with the Bioruptor water bath sonicator (Diagenode, Sparta, NJ) to an average size of 500 bp to 1 kb. The complexes were precleared with protein A-agarose (Pierce) and incubated overnight with specific antibodies, which are listed in the supplemental text. Immunoadsorbed complexes were captured on protein A-agarose (exception: RNA polymerase II mouse monoclonal antibody was bound to streptavidin-agarose (Thermo) previously incubated with 5 μg/immunoprecipitation of goat anti-mouse IgG) and washed once with TE8 (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 0.5 m EDTA). Agarose-bound complexes were then resuspended in TE8, layered on top of a sucrose solution (1 m sucrose, 200 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40), and centrifuged for 3 min. Agarose-bound complexes were then washed once with 0.5× radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, followed by four washes with TE8. The samples were eluted off the agarose using 200 μl of elution buffer (100 mm NaHCO3, 1%SDS), and cross-links were reversed at 65 °C overnight. Eluted DNA was isolated, washed, and concentrated using the ChIP DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (ZYMO Research). Immunoadsorbed DNA was analyzed by PCR and/or quantitative real time PCR.

Gene Silencing

Specific protein levels were decreased using the Dharmacon small interfering RNA (siRNA) (control oligonucleotide D001810-0X, AHR oligonucleotide J004990-07, ARNT oligonucleotide D007207-01, RELB oligonucleotide J004767-06, HDAC1 oligonucleotide J003493-10, and HDAC3 oligonucleotide J003496-09). Electroporation/nucleofection was performed using the Amaxa nucleofection system essentially as described in the manufacturer protocols. Briefly, the cells were washed and suspended at a concentration of 2.0 × 106/100 μl of nucleofection solution. Control or targeted siRNA was added to the sample for a final concentration of 1.5 μmol/liter. The samples were electroporated using the manufacturer's MCF-7 high efficiency program and plated into six-well dishes in complete medium.

Transient siRNA-mediated Ablation of Endogenous AHR and Replacement with Transfected Construct

The experiments were carried out as described by DiNatale and Perdew (20). Briefly, MCF-7 cells were electroporated with a control or AHR-targeted siRNA, along with control pcDNA3, pcDNA3-AHR, or pcDNA3-AHR-GS.

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assay

CV-1 cells were grown in penicillin/streptomycin-free medium and transfected using the Mirus TransIT-TKO transfection system. Transfection was performed with control pGL3-promoter, pGL3–3.0kb, or pGL3–3.0kb.synth vectors. Beginning 24 h after transfection, the cells were treated for an additional 24 h, rinsed with PBS, and lysed in cell culture lysis buffer (2 mm trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, and 1% Triton X-100). Cytosol was assayed for luciferase activity using the a luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) as specified by the manufacturer. Light production was measured using a TD-20e luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA).

RESULTS

IL6 Synergy Requires IL1β Receptor and AHR-ARNT Pathway Signaling

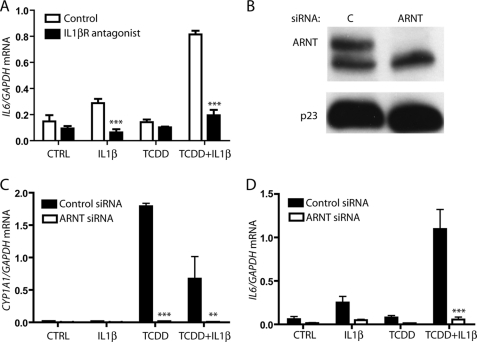

Having previously shown that IL6 is synergistically induced in MCF-7 cells via AHR activation in conjunction with IL1β treatment, the signaling mechanism by which this event occurs was explored. MCF-7 cells pretreated with 250 ng/ml of IL1β receptor antagonist (R & D Systems; 280-RA/CF) for 1 h were subsequently treated with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or co-treated with IL1β and TCDD. Pretreatment with IL1β receptor antagonist prevented IL1β signaling and inhibited any significant increase in IL6 mRNA production (Fig. 1A). These data indicate that IL1β is working through its membrane receptor to activate IL6 expression.

FIGURE 1.

Synergistic IL6 induction requires IL1β receptor signaling and AHR-ARNT proteins. A, serum-starved MCF-7 cells were pretreated for 1 h with vehicle or 250 ng/ml IL1 receptor antagonist prior to treatment with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or TCDD+IL1β for 2 h. Total RNA was then isolated, cDNA was prepared, and relative IL6 mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real time PCR. B, MCF-7 cells were electroporated with control (C) or ARNT siRNA, plated for 24 h, and serum-starved for 18 h, and whole cell extracts were prepared. Expressed levels of ARNT and p23 (control) were assessed by immunoblot. C and D, MCF-7 cells were electroporated, plated into 6-well dishes, and then serum-starved before being treated for 2 h with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or TCDD+IL1β. Total RNA was isolated, cDNA was prepared, and relative CYP1A1 and IL6 mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real time PCR.

Our prior research has shown that siRNA-mediated ablation of AHR protein prevents synergistic IL6 induction (6). To clarify the manner in which the AHR participates in IL6 induction, the AHR signaling pathway was dissected, beginning with its heterodimerization partner, ARNT. siRNA-mediated ablation of ARNT protein levels was carried out, and MCF-7 cells were treated for 2 h with vehicle, IL1β, TCDD, or with a combination of these substances. Electroporation of MCF-7 cells with ARNT-targeting siRNA leads to nearly complete ablation of protein levels (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 1C, the loss of ARNT prevents TCDD-induced CYP1A1 expression, as expected. Similarly, ARNT is shown to be necessary for synergistic IL6 induction (Fig. 1D). This finding suggests that AHR/ARNT heterodimerization is required for AHR-mediated induction of IL6 expression.

The Role of AHR in IL6 Induction Requires DRE Binding

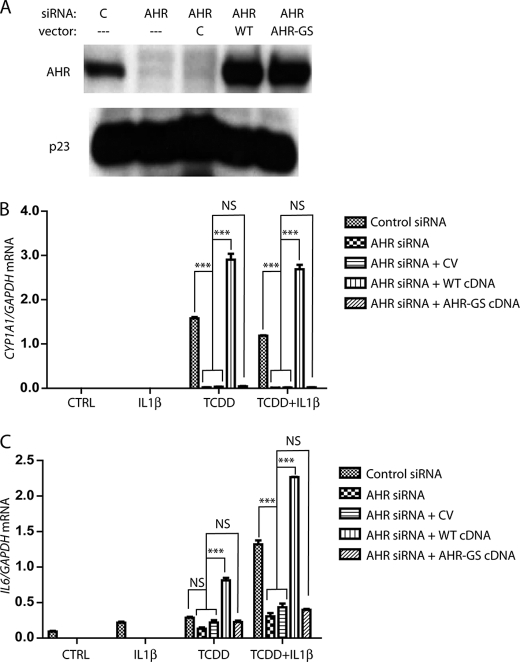

The AHR has been shown to play a role in regulatory pathways via AHR/ARNT-mediated binding to DRE sequences, as well as through protein-protein interactions. To determine whether the induction of IL6 required the AHR/ARNT heterodimer to bind to the gene promoter region, we replaced AHR protein expression with that of a DNA-binding mutant in MCF-7 cells. A characterized DNA-binding variant of the murine AHR that contains GS amino acid sequence inserts between residues has been shown not to have altered ligand binding, interaction with chaperones, or heterodimerization but is not capable of binding to DREs (21). This mutation was created in human AHR (AHR-GS) and similarly characterized (supplemental text and Fig. S1). Having optimized electroporation conditions to attain nearly complete siRNA-mediated ablation of AHR protein in MCF-7 cells, receptor levels were reduced, and cells were co-transfected with a vector containing a synthetic, codon-optimized AHR cDNA construct that was not targeted by AHR siRNA. The AHR constructs expressing AHR or AHR-GS were utilized. This method of transient protein replacement has been previously characterized (20). Co-transfection with a control vector resulted in minimal change in AHR protein ablation. AHR expression and AHR-GS expression were equivalent although higher than basal AHR protein expression (Fig. 2A). The prototypical AHR target gene examined following ligand activation is CYP1A1. Although AHR knockdown resulted in the loss of CYP1A1 induction following TCDD treatment, the replacement with ectopic AHR expression rescued induction at a higher level because of the higher receptor expression. Treatment with TCDD following replacement of endogenous AHR protein with the AHR-GS mutant failed to induce CYP1A1 because of the loss of DRE binding in the CYP1A1 enhancer (Fig. 2B). Similarly, a loss of AHR expression prevents the synergistic induction of IL6 following combined IL1β and TCDD treatment, whereas replacement with a fully functional AHR protein allows for synergy to occur. Replacement of endogenous AHR with AHR-GS fails to rescue the induction of IL6 (Fig. 2C). Thus DRE binding appears to be required for the AHR to play a role in synergistic IL6 induction, as opposed to simply being the result of AHR-protein interactions.

FIGURE 2.

Inability to bind to DNA prevents AHR from inducing IL6 synergy. A, MCF-7 cells were transfected with control or AHR targeting siRNA oligonucleotides, with or without pcDNA3 vector. The vectors used were control (lane C), WT cDNA synthetic hAHR-pcDNA3, or AHR-GS-pcDNA3. 24 h after transfection, the cells were serum-starved for 18 h, whole cell extracts were prepared, and protein levels of AHR and p23 (control) were assessed by immunoblot. B and C, MCF-7 cells were electroporated, plated into 6-well dishes, and then serum-starved before being treated for 2 h with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or TCDD+IL1β. The relative IL6 and CYP1A1 mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real time PCR. WT, wild type. CV, control vector.

Imperfect DREs in the IL6 Promoter Are Able to Bind the AHR

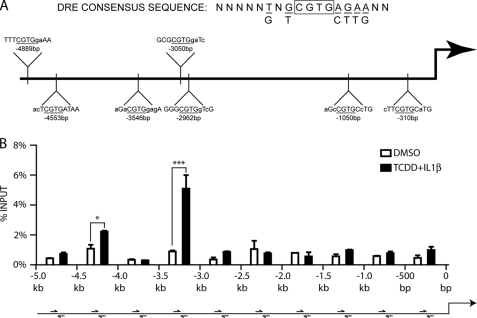

DRE sequences have been characterized for their AHR binding ability, and the optimal nucleotide sequence has been determined. Having established that AHR/ARNT binding to a DRE is required for AHR ligand-mediated induction of IL6, we wanted to determine which imperfect DRE(s) in the IL6 promoter are functional. Integral to receptor binding is the core (G/T)CGTG sequence, with flanking nucleotides being less important but increasing the affinity of the AHR for the DNA. Functional analyses have shown that having a G as the 5′ base of the core enhances binding and function of receptor (22). However, studies have shown a lack of correlation between AHR binding to imperfect DREs in gel shift analyses and AHR-mediated induction of imperfect DRE-driven luciferase assays (23, 24). This led to the conclusion that, with a modification of the 5′ core nucleotide, there is still potential for some receptor binding in the genomic context, thus creating the need to assess sequences containing only the four central bases of CGTG. Sequence analysis of the IL6 promoter reveals seven imperfect DREs in the span from the transcription start site to 5 kb upstream. All seven DREs contain the core CGTG sequence, but many have less than optimal flanking sequences (Fig. 3A). Initial attempts at luciferase assays using large stretches of the IL6 promoter show an inability to mimic the regulation observed in cells. This finding is not surprising, because previous research has encountered the same problem (25), such that the length of the promoter used in the assay is inversely proportional to the level of induction (supplemental Fig. S2). Because these limitations prevented a full promoter analysis utilizing reporter vectors, a different approach was adopted. MCF-7 cells treated with either vehicle or combinatorial TCDD and IL1β for 2 h were subjected to ChIP analysis of the IL6 promoter. Quantitative real time PCR was carried out using primers that scanned the 5 kb upstream from the transcription start site in 500-bp fragments. Maximal occupancy increases following treatment were observed in the region of the multiple DREs between −3.kb and −3.5 kb and, to a lesser extent, in the −4.5-kb region (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Numerous imperfect DREs in the IL6 promoter have the potential to bind the AHR. A, imperfect DREs containing the four immutable core nucleotides are present in seven locations within the first 5 kb upstream from transcription start site. B, ChIP analysis of the IL6 promoter followed by quantitative real time PCR of samples with scanning primers amplifying 500-bp segments.

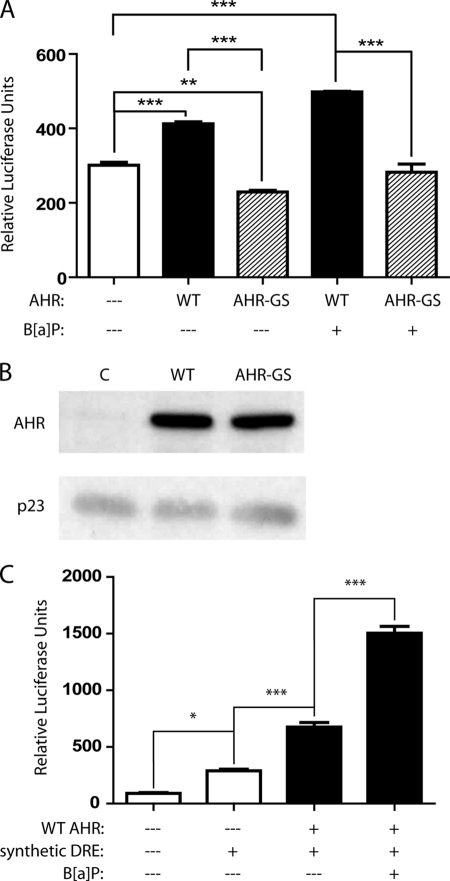

Further analysis of the −3.0-kb region was carried out, because it included imperfect DREs at −2962 and −3050 bp (Fig. 3A). Both of these DREs contain a 5′ G next to the core CGTG, and their close proximity to each other could prompt a greater AHR-mediated effect. pGL3–3.0kb vector, which contained both the −2962-bp and the −3050-bp DREs, was transfected into the CV-1 cell line. The combination of a low level of basal activated AHR in CV-1 cells (26) and the promoter contained within the pGL3 vector led to luciferase activity in the absence of transfected AHR or exogenous ligand (Fig. 4A, first column). Co-transfection with the WT AHR-expressing construct led to a significant increase with the −3.0-kb vector (Fig. 4A, second column), whereas co-transfection of the luciferase vector and the AHR-GS construct led to a significant decrease in luciferase activity compared with basal levels (Fig. 4A, third column) and, therefore, a significant difference between co-transfection with WT AHR compared with mutant AHR-GS. This is believed to be due to the mutant AHR binding a portion of the putative endogenous ligand and heterodimerizing with ARNT, sequestering part of the ARNT pool, and thus decreasing basal luciferase activity. Co-transfection of the reporter vector and WT AHR-expressing vector, followed by 24 h of treatment with 5 μm of the AHR ligand B[a]P, resulted in a significant 1.7-fold increase in luciferase activity, which is not observed upon expression of the DNA-binding mutant AHR-GS (Fig. 4A, fourth and fifth columns). Increases in AHR protein levels following co-transfection with both the AHR and AHR-GS were detected by Western blot (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

DREs in the −3.0-kb region of the IL6 promoter can bind the AHR. CV-1 cells were co-transfected with combinations of control pcDNA3 vector, pcDNA3-AHR, or pcDNA3-AHR-GS, along with a reporter vector. The cells were subsequently treated for 24 h with vehicle or 5 μm B[ay]P and then lysed, and a luciferase assay was performed. A, co-transfection with pGL3–3.0kb: 250 bases of the IL6 promoter centered on the midway point between the two DREs flanking the −3.0-kb position. B, separate samples of CV-1 cells were transfected as above and plated, then whole cell extracts were prepared, and the protein levels of AHR and p23 (control) were assessed by immunoblot. C, co-transfection with pGL3–3.0kb.synth: oligonucleotide synthesized with the DRE located at −3050 bp in triplicate. WT, wild type.

To further validate the functionality of the −3050 bp DRE, pGL3–3.0kb.synth vector, which contained three copies of the DRE in tandem, was transfected into CV-1 cells. As seen with the endogenous promoter construct, transfection of the vector alone resulted in basal luciferase activity caused by the low level of constitutively active AHR in CV-1 cells (Fig. 4C, second column). Addition of the WT AHR construct resulted in greater basal luciferase activity (Fig. 4C, third column), which was increased nearly 3-fold following B[a]P treatment (Fig. 4C, fourth column). The lower, albeit significant level of induction mediated by the promoter construct in Fig. 4A is not altogether surprising, because studies utilizing luciferase vectors containing a single DRE have shown low levels of AHR-mediated inducibility (27). Nevertheless, these studies clearly establish that the imperfect DREs at −3.0 kb in the IL6 promoter are functional.

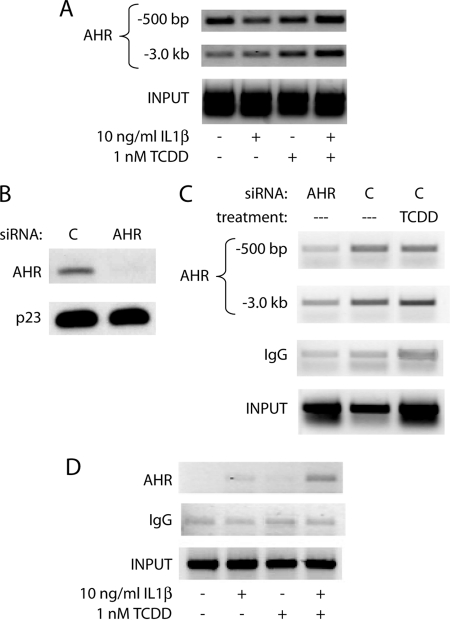

AHR Occupies Regions Where Imperfect DREs Are Present at the IL6 Promoter in Cells

The next step was to more fully address at what level the AHR actually binds to the IL6 promoter at or near the location of the functional imperfect DREs within the cellular context. ChIP assays were performed in MCF-7 cells following a 2-h treatment with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or a combination. Correlating with the scanning of the IL6 promoter in Fig. 3, AHR binding in the region of the −3.0-kb DREs increased greatly upon TCDD or combinatorial treatment (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, there appeared to be a basal level of AHR occupancy near the transcription start site, with a slight increase following combinatorial treatment. This could be due to a combination of slight AHR binding to the imperfect DRE at −310 bp and a chromatin looping effect, where the upstream bound AHR affects the complexes bound in the proximal promoter. The fluidity of factors found on the promoter initially following treatment could also account for the low level of AHR found in the proximal promoter, because many remodeling effects would be transient in nature. Basal occupancy at the IL6 promoter may be due to endogenous AHR ligands produced in cells, and/or AHR ligands in the cell culture medium. To address this point, AHR levels were ablated in MCF-7 cells using electroporation of siRNA oligonucleotides, and ChIP assays were performed to assess basal AHR levels at the IL6 promoter. As shown previously, nucleofection of MCF-7 cells led to a nearly complete loss of AHR protein 48 h after transfection (Fig. 5B). As expected, ablation of AHR protein leads to a marked reduction in AHR occupancy of the IL6 promoter in comparison with control siRNA in the absence of exogenous ligand (Fig. 5C). This establishes that there is a significant basal AHR occupancy at the IL6 promoter. TCDD treatment led to a marked increase in AHR occupancy at −3.0 kb, further suggesting that the −3.0-kb region may be a key contributor to TCDD-mediated increase in IL6 transcription. Our previous research has shown that, with an initial treatment of IL1β and TCDD, IL6 induction continues up to 72 h with no sign of abating (6). Although ChIP assays are often performed within 1–2 h of treatment to assess initial changes in gene promoters that allow for transcriptional activity, a ChIP assay performed 6 h following treatment showed a dramatic increase in AHR occupancy of the IL6 promoter in the −500-bp region after combinatorial treatment (Fig. 5D). This finding supports the hypothesis that any looping effects that occur immediately after treatment are in flux but may be required for synergistic induction over time.

FIGURE 5.

AHR is present at the IL6 promoter in the region of the transcription start site and −3.0-kb DREs and remains over time. A, ChIP analysis of the MCF-7 IL6 promoter following 2 h of treatment with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or TCDD+IL1β. AHR was immunoprecipitated, and DNA was amplified using primers for the region specified upstream from the transcription start site. B, MCF-7 cells were electroporated with control or AHR targeted siRNA oligonucleotides, plated for 24 h, and serum-starved for 18 h. Whole cell extracts were prepared, and protein levels of AHR and p23 (control) were assessed by immunoblot. C, MCF-7 cells were electroporated and serum-starved as above and then treated for 2 h with vehicle control or 10 nm TCDD. ChIP analysis of the IL6 promoter was then carried out, and DNA was amplified using primers for the region specified upstream from the transcription start site. D, ChIP analysis of the MCF-7 IL6 promoter following 6 h of treatment with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or TCDD+IL1β. AHR was immunoprecipitated, and DNA in the region of −500 bp upstream from the transcription start site was amplified.

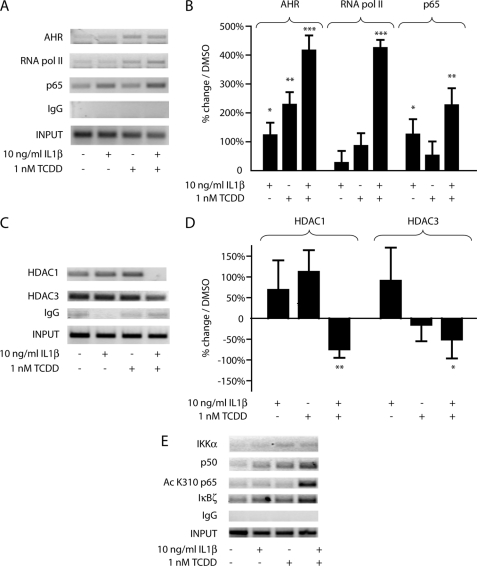

AHR Recruitment to the IL6 Promoter Coincides with a Shift in Occupancy from Transcriptional Repressors to Activators

Increased AHR occupancy of the IL6 promoter following combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment coincides with increased transcriptional activity, but the mechanism by which this occurs remained unclear. ChIP analysis of the IL6 promoter showed that with enhanced AHR occupancy came increased occupancy of RNA polymerase II and the NF-κB subunit p65 in the region of the transcription start site (Fig. 6, A and B). The increase in p65 presence but the relative lack of RNA polymerase II occupancy following IL1β treatment alone suggested that AHR occupancy of the IL6 promoter coincided with a second aspect of regulation that allowed for maximal transcriptional increase.

FIGURE 6.

AHR occupancy of the IL6 promoter corresponds to a decrease in co-repressors and an increase in co-activators. ChIP analyses of the MCF-7 IL6 promoter following 2 h of treatment with vehicle, 10 ng/ml IL1β, 1 nm TCDD, or TCDD+IL1β. Immunoprecipitations for the specified proteins were performed, and DNA was amplified for gel electrophoresis or quantitative real time PCR. Negative controls for quantitative real time PCR are shown in supplemental Fig. S3.

In analyzing other proteins associated with the region immediately upstream of the transcription start site, combinatorial treatment was shown to result in not only an increase in activators but also a loss of repressors. Following 2 h of combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment, the nearly complete eradication of HDAC1 occupancy and a drop in HDAC3 presence exemplify the loss of co-repressor complexes (Fig. 6, C and D). These results would, at least in part, explain why combinatorial treatment is required for significant IL6 induction; aspects of derepression as well as transcriptional activation must take place. Interestingly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of HDAC1 and HDAC3 did not increase IL6 synergy but repressed it (supplemental Fig. S4). The fact that treatments were carried out 48 h following knockdown would suggest that HDAC loss leads to a more closed DNA conformation, an obstacle not overcome by subsequent treatments.

As an NF-κB regulated gene, the IL6 promoter was analyzed for subunits and modifiers indicative of canonical and noncanonical NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activation. In the region of the transcription start site, the p65 presence increases following IL1β treatment with and without TCDD. However, the p50 subunit presence is much higher with combinatorial treatment. The p50-p65 heterodimer is generally associated with the most active form of NF-κB transcriptional activation. Likewise, combinatorial treatment leads to a significant increase in acetylation of p65 and in the presence of IκBζ, both of which are associated with maximal activation potential of NF-κB (Fig. 6E). The presence of K310-acetylated p65 is of great importance, because this modification has been shown to be necessary for full transcriptional activation (18, 28, 29). NF-κB activity is also mediated through various mechanisms involving the IKKα and IKKβ proteins in the cytoplasm, and evidence exists for a nuclear role for IKKα at gene promoters. ChIP assays show a low level of IKKα at the IL6 promoter following TCDD treatment, in conjunction with AHR occupancy (Fig. 6E). IKKβ is not present at the promoter (supplemental Fig. S5). The noncanonical NF-κB pathway involving RELB has been tied to AHR activation in specific contexts (30, 31), and RELB activation has been shown to be more dependent upon IKKα than IKKβ, the converse of RELA (32–35). The possible involvement of RELB in IL6 synergistic induction was tested through the use of siRNA-mediated ablation of RELB expression. The reduction in RELB protein levels had no effect on IL1β- and TCDD-mediated induction of IL6 (supplemental Fig. S6).

The scenario that emerges at the IL6 promoter following combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment is thus one of a confluence of factors ending in transcriptional activation. Analysis of some other transcription factors and DNA modifications commonly associated with inflammatory signaling and transcriptional activation/repression in MCF-7 cells failed to show a correlation with synergistic IL6 expression. Factors such as CCAAT enhancer-binding protein β, c-Jun, cAMP-responsive element-binding protein-binding protein, and BRG1, as well as DNA acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, and various other co-repressors, all show variation following IL1β or TCDD treatment (supplemental Fig. S5). However, no clear pattern consistent with complete activation/derepression emerges.

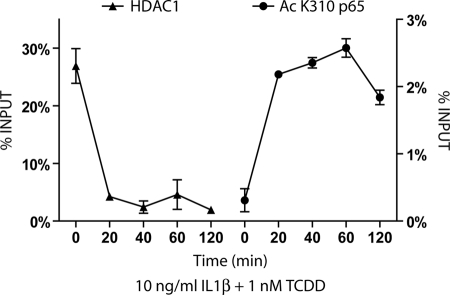

In contrast, real time PCR quantification of ChIP assays at times 0, 20, 40, 60, or 120 min following combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment revealed a loss of HDAC1 and an increase of acetylated p65 at the IL6 promoter, which is strongly indicative of the loss of repression and full NF-κB activation (Fig. 7). It would appear that IL1β treatment allows for the expected increased NF-κB occupancy of the promoter, whereas AHR activation is required for certain aspects of derepression, such as dismissal of HDAC1. In this manner, the activated AHR allows for full induction of what would otherwise be a tempered NF-κB-mediated gene response.

FIGURE 7.

Combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment leads to early HDAC1 dismissal and acetylated p65 recruitment at the IL6 promoter. ChIP analysis was performed at the IL6 promoter at time 0 and following 20, 40, 60, and 120 min of treatment with 1 nm TCDD and 10 ng/ml IL1β. DNA samples immunoprecipitated with HDAC1 or Ac K310 p65 antibodies were quantified using real time PCR primers amplifying the −500-bp upstream region and at the transcription start site, respectively.

DISCUSSION

A ligand-activated transcription factor, the AHR has been shown to play various roles in inflammatory gene responses, acting as either an enhancer or a repressor, depending on context (1). The variety of mechanisms through which the AHR affects inflammation led to the current study, which examines how ligand-activated AHR allows for synergistic IL6 expression following IL1β co-treatment in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. In numerous cell types, IL6 is induced through IL1β or other inflammatory signaling. This is not always the case, however, and comparisons of highly metastatic MDA-MB231 and weakly metastatic MCF-7 breast cancer cells have shown drastic differences in the expression of transcription factors found at the IL6 promoter, as well as in the accessibility of the IL6 promoter in general (36). A more open chromatin structure at the IL6 promoter in invasive/metastatic lines would explain the characteristic high basal expression or a highly inducible IL6 promoter, leading to increased gene expression. Similarly, research has shown that treatment of weakly invasive breast cancer cells with exogenous IL6 increases the cellular migration/invasion (12), thus pointing to a possible autocrine loop correlating high IL6 expression with high metastatic potential. In this context, understanding the mechanism by which weakly metastatic MCF-7 cells are subject to AHR- and IL1β-mediated synergistic IL6 induction for prolonged periods of time (6) could explain how cells might initiate the IL6 autocrine loop. These cells might then be able to express a more aggressive phenotype similar to that of MDA-MB231 cells without the associated increases in inflammatory transcription factors and specific DNA modifications seen in typical IL6-responsive cells.

The DNA binding ability of the AHR has been characterized predominantly by its nucleotide sequence in the context of CYP1A1 inducibility, reporter constructs, or affinity with DNA as determined by gel shift experiments (22). The ideal DRE to which the AHR and ARNT binds is 11 nucleotides long, although only the four central nucleotides are immutable, and current analyses of AHR function generally assess a core of five nucleotides, GCGTG. The 5′ G of this core appears necessary for transcriptional activation but is not required for in vitro DNA binding. EMSA experiments coupled with reporter assays have shown that the DNA binding ability of imperfect DREs do not always correlate with activation potential (23, 24). In addition, imperfect DREs have been shown to bind the AHR in gene promoter regions, with various effects on gene transcription (24, 37, 38). It remains unclear whether activated AHR that was found at increased levels in the region of imperfect TCGTG DREs in the −4.5-kb region of the IL6 promoter is required for synergistic induction (Fig. 3). The single TCGTG DRE 310 bp upstream may similarly bind a level of receptor that, although low, has an effect on complex formation at the transcription start site.

Although TCDD treatment has variable effects on IL6 production depending on the cell type (39, 40), the mechanism by which activated AHR influences the IL6 gene and the complex in which it plays a role has not been fully studied. Our analysis of the IL6 promoter showed that the receptor binds 3 kb upstream but in ChIP analysis can be found closer to the transcription start site, as well. Evidence points to AHR-mediated synergy occurring via distal DRE binding and potential chromatin looping to effect change nearer the transcription start site (Figs. 4 and 5). The notion that the AHR is able to bind to distal, imperfect DREs in the promoter regions of genes and influence gene transcription has significant implications for the overall role of the receptor in transcriptional regulation. This would especially be the case for genes in which a second signal is needed in conjunction with AHR binding to lead to alterations in transcription, such as IL6. Thus looking at imperfect DREs for AHR binding and promoter regulation could open up numerous genes and promoter regions for study.

IL1β has been shown to markedly induce IL6 expression in a number of cell lines, including intestinal epithelial and orbital fibroblasts (41, 42). The mechanism of IL6 expression in highly responsive tissues has been studied extensively, with NF-κB being a central factor in mediating transcriptional activity, yet these studies yield little insight into the mode of IL6 regulation in MCF-7 cells. Analysis of various regions of the IL6 promoter following combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment begins to explain how activated AHR, binding to imperfect DREs in the promoter region, can affect the co-repressor/co-activator complexes occupying the region upstream of the transcription start site. The effects of AHR combined with changes caused by IL1β treatment and subsequent NF-κB activation together enhance IL6 transcription. Only with combinatorial treatment are repressive complexes minimized and full NF-κB activation achievable.

The mechanism by which NF-κB-mediated transcription is repressed in the absence of activated AHR appears to involve basal occupancy of the IL6 promoter by co-repressors that include HDAC1 and HDAC3. This is consistent with reports of numerous mechanisms of interplay between these and other, secondary factors. Mechanisms by which IL1β can derepress NF-κB target genes in other settings (28, 43, 44) fail to have the same effect on IL6. For this reason, the lack of derepression following IL1β treatment alone renders any increase in p50-p65 heterodimer at the promoter moot. HDAC inhibitors have been shown to have an effect on IL6 production by preventing deacetylation of histone H3 as well as p65, the latter of which leads to deactivation of the NFκB subunit (17, 45). Also, ligand-activated AHR/ARNT occupancy at the CYP1A1 promoter has been shown to lead to dismissal of HDAC1 complexes. This repressor complex plays a major role in maintaining the CYP1A1 promoter in a silent chromatin configuration via multiple DNA modifications (46).

Corresponding with the dismissal of co-repressors upon combinatorial treatment is the recruitment of multiple NF-κB pathway co-activators. The increased presence of IKKα is known to play a role in histone phosphorylation and tumor necrosis factor α-mediated gene activation (47). One result of the dismissal of HDACs that can deactivate p65 and inhibit transcription is an increased presence of K310-acetylated p65, a modification necessary for maximal transcriptional ability (18, 28, 29, 48). Null mouse models prove that endogenous IκBζ is physiologically necessary for IL1-mediated IL6 induction (15, 49). Additionally, IκBζ has been shown to interact with BRG1, one of two ATP engines of the mammalian SWI·SNF complex, and thereby localize to points of chromatin remodeling (50), which coincides with combinatorial treatment in MCF-7 cells (supplemental Fig. S5).

Synergistic IL6 induction following AHR activation and IL1β signaling in MCF-7 cells is dependent upon the presence of AHR/ARNT and subsequent DRE binding. The interplay between AHR and IL1β signaling and its effect on the IL6 promoter is exceedingly complex, and numerous secondary transcription factors appear at various levels. Importantly, these results suggest that the AHR may regulate other genes in a similar manner. Gene promoters that are basally occupied by co-repressor complexes and contain imperfect DREs have the potential to be derepressed by an AHR that is activated by either an endogenous or exogenous ligand. The finding in Fig. 1C that ARNT knockdown further lowers basal IL6 expression in MCF-7 cells points to a role for AHR/ARNT heterodimer in promoting a constitutive level of open, derepressed regulatory region. Synergistic activation of IL6 following combinatorial IL1β and TCDD treatment appears to include the dismissal of co-repressors by DNA-bound AHR in the upstream region, allowing for occupancy and activation by IL1β-induced NF-κB. With this understanding, the therapeutic potential for an AHR antagonist becomes clear. The ability to prevent endogenous and exogenous ligands from activating the AHR and thus derepressing the IL6 promoter would allow for a novel mechanism by which pro-growth signaling in the tumor microenvironment could be minimized. Research has shown that higher levels of nuclear AHR in human tumor samples correlate with poorer prognosis and more aggressive disease (51). The source of AHR activation in these patients remains unclear. With TCDD exposure tied to numerous changes including cytokine levels, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) expression, and cell cycle and apoptosis regulators, endogenously activated AHR could be regulating transcription of numerous genes in a similar manner to IL6.

Supplementary Material

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental text and Figs. S1–S6.

- AHR

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- ARNT

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- DRE

- dioxin response element

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase

- TCDD

- 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- B[a]P

- benzo[a]pyrene

- CYP

- cytochrome P450

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beischlag T. V., Luis Morales J., Hollingshead B. D., Perdew G. H. (2008) Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 18, 207–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura A., Naka T., Nohara K., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Kishimoto T. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9721–9726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel R. D., Murray I. A., Flaveny C. A., Kusnadi A., Perdew G. H. (2009) Lab. Invest. 89, 695–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kharat I., Saatcioglu F. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 10533–10537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furness S. G., Whelan F. (2009) Pharmacol. Ther. 124, 336–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollingshead B. D., Beischlag T. V., Dinatale B. C., Ramadoss P., Perdew G. H. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 3609–3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasser A. K., Sullivan N. J., Studebaker A. W., Hendey L. F., Axel A. E., Hall B. M. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 3763–3770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armenante F., Merola M., Furia A., Tovey M., Palmieri M. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4483–4490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavarretta I. T., Neuwirt H., Untergasser G., Moser P. L., Zaki M. H., Steiner H., Rumpold H., Fuchs D., Hobisch A., Nemeth J. A., Culig Z. (2007) Oncogene. 26, 2822–2832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conze D., Weiss L., Regen P. S., Bhushan A., Weaver D., Johnson P., Rincón M. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 8851–8858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asgeirsson K. S., Olafsdóttir K., Jónasson J. G., Ogmundsdóttir H. M. (1998) Cytokine 10, 720–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badache A., Hynes N. E. (2001) Cancer Res. 61, 383–391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sasser A. K., Mundy B. L., Smith K. M., Studebaker A. W., Axel A. E., Haidet A. M., Fernandez S. A., Hall B. M. (2007) Cancer Lett. 254, 255–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sansone P., Storci G., Tavolari S., Guarnieri T., Giovannini C., Taffurelli M., Ceccarelli C., Santini D., Paterini P., Marcu K. B., Chieco P., Bonafè M. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3988–4002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto M., Takeda K. (2008) J. Infect. Chemother. 14, 265–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkins N. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quivy V., Van Lint C. (2004) Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 1221–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L. F., Greene W. C. (2003) J. Mol. Med. 81, 549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuwata H., Matsumoto M., Atarashi K., Morishita H., Hirotani T., Koga R., Takeda K. (2006) Immunity 24, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiNatale B. C., Perdew G. H. (2010) Cytotechnology, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunger M. K., Glover E., Moran S. M., Walisser J. A., Lahvis G. P., Hsu E. L., Bradfield C. A. (2008) Toxicol. Sci. 106, 83–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denison M. S., Elferink C. F., Phelan D. (1998) in Toxicant-Receptor Interactions in the Modulation of Signal Transduction and Gene Expression (Denison M. S., Helferich W. G. eds) pp. 3–33, Taylor and Francis, London [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson H. I., Chan W. K., Bradfield C. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26292–26302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillesby B. E., Stanostefano M., Porter W., Safe S., Wu Z. F., Zacharewski T. R. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 6080–6089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faggioli L., Costanzo C., Merola M., Bianchini E., Furia A., Carsana A., Palmieri M. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem. 239, 624–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiaro C. R., Patel R. D., Marcus C. B., Perdew G. H. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 72, 1369–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gouédard C., Barouki R., Morel Y. (2004) Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 5209–5222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoberg J. E., Popko A. E., Ramsey C. S., Mayo M. W. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 457–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L. F., Mu Y., Greene W. C. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 6539–6548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baglole C. J., Maggirwar S. B., Gasiewicz T. A., Thatcher T. H., Phipps R. P., Sime P. J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28944–28957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogel C. F., Sciullo E., Matsumura F. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 363, 722–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Y., Fang F., St Clair D. K., Sompol P., Josson S., St Clair W. H. (2008) Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 2367–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao G., Harhaj E. W., Sun S. C. (2001) Mol. Cell 7, 401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senftleben U., Cao Y., Xiao G., Greten F. R., Krähn G., Bonizzi G., Chen Y., Hu Y., Fong A., Sun S. C., Karin M. (2001) Science 293, 1495–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dejardin E., Droin N. M., Delhase M., Haas E., Cao Y., Makris C., Li Z. W., Karin M., Ware C. F., Green D. R. (2002) Immunity 17, 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ndlovu N., Van Lint C., Van Wesemael K., Callebert P., Chalbos D., Haegeman G., Vanden Berghe W. (2009) Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 5488–5504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safe S., Krishnan V. (1995) Arch. Toxicol. Suppl. 17, 99–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Safe S., Wang F., Porter W., Duan R., McDougal A. (1998) Toxicol. Lett. 102–103, 343–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frericks M., Burgoon L. D., Zacharewski T. R., Esser C. (2008) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 232, 268–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi S., Okamoto H., Iwamoto T., Toyama Y., Tomatsu T., Yamanaka H., Momohara S. (2008) Rheumatology 47, 1317–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hershko D. D., Robb B. W., Luo G., Hasselgren P. O. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283, R1140–R1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen B., Tsui S., Smith T. J. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 1310–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Privalsky M. L. (2004) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66, 315–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gloire G., Horion J., El Mjiyad N., Bex F., Chariot A., Dejardin E., Piette J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 21308–21318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Lf., Fischle W., Verdin E., Greene W. C. (2001) Science 293, 1653–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnekenburger M., Peng L., Puga A. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1769, 569–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anest V., Hanson J. L., Cogswell P. C., Steinbrecher K. A., Strahl B. D., Baldwin A. S. (2003) Nature 423, 659–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashburner B. P., Westerheide S. D., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (2001) Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 7065–7077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto M., Yamazaki S., Uematsu S., Sato S., Hemmi H., Hoshino K., Kaisho T., Kuwata H., Takeuchi O., Takeshige K., Saitoh T., Yamaoka S., Yamamoto N., Yamamoto S., Muta T., Takeda K., Akira S. (2004) Nature 430, 218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kayama H., Ramirez-Carrozzi V. R., Yamamoto M., Mizutani T., Kuwata H., Iba H., Matsumoto M., Honda K., Smale S. T., Takeda K. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12468–12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ishida M., Mikami S., Kikuchi E., Kosaka T., Miyajima A., Nakagawa K., Mukai M., Okada Y., Oya M. (2010) Carcinogenesis. 31, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.