Abstract

Alginate, a major component of the cell wall matrix in brown seaweeds, is degraded by alginate lyases through a β-elimination reaction. Almost all alginate lyases act endolytically on substrate, thereby yielding unsaturated oligouronic acids having 4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronic acid at the nonreducing end. In contrast, Agrobacterium tumefaciens alginate lyase Atu3025, a member of polysaccharide lyase family 15, acts on alginate polysaccharides and oligosaccharides exolytically and releases unsaturated monosaccharides from the substrate terminal. The crystal structures of Atu3025 and its inactive mutant in complex with alginate trisaccharide (H531A/ΔGGG) were determined at 2.10- and 2.99-Å resolutions with final R-factors of 18.3 and 19.9%, respectively, by x-ray crystallography. The enzyme is comprised of an α/α-barrel + anti-parallel β-sheet as a basic scaffold, and its structural fold has not been seen in alginate lyases analyzed thus far. The structural analysis of H531A/ΔGGG and subsequent site-directed mutagenesis studies proposed the enzyme reaction mechanism, with His311 and Tyr365 as the catalytic base and acid, respectively. Two structural determinants, i.e. a short α-helix in the central α/α-barrel domain and a conformational change at the interface between the central and C-terminal domains, are essential for the exolytic mode of action. This is, to our knowledge, the first report on the structure of the family 15 enzyme.

Keywords: Bacterial Metabolism, Enzyme Structure, Polysaccharide, Site-directed Mutagenesis, X-ray Crystallography, Agrobacterium, Alginate, Enzyme Catalysis, Exotype, Lyase

Introduction

Carbohydrate-active enzymes such as glycoside hydrolases, polysaccharide lyases, glycosyl transferases, and carbohydrate esterases are categorized into more than 200 families based on amino acid sequences in the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes (CAZy) data base (1). Polysaccharide lyases (PLs)2 are classified into 21 PL families and they play an important role in degrading acidic polysaccharides such as polygalacturonan, rhamnogalacturonan, alginate, chondroitin, hyaluronan, heparin, heparan, and xanthan. These lyases commonly recognize uronic acid residues in polysaccharides, catalyze β-elimination, and produce unsaturated saccharides with C=C double bonds at nonreducing terminal uronate residues.

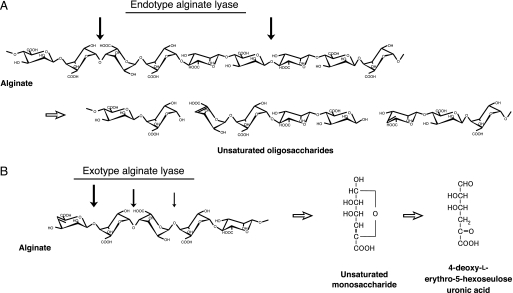

Alginate, produced by brown seaweeds as a major component of the cell wall matrix, is a linear polysaccharide composed of α-l-guluronate (G) and its C5 epimer β-d-mannuronate (M). Three blocks, such as poly-α-l-guluronate (poly(G)), poly-β-d-mannuronate (poly(M)), and heteropolymeric random sequences (poly(MG)), constitute the alginate polymer (2). The alginate degradation pathway has been characterized in some bacteria, virus, and abalone. In the bacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain A1, alginate is directly incorporated into the cytoplasm by the cell surface pit, periplasmic binding proteins, and ATP-binding cassette transporter. The incorporated alginate is subsequently depolymerized into unsaturated disaccharides, trisaccharides, and tetrasaccharides through the action of three cytoplasmic endotype alginate lyases, A1-I, A1-II, and A1-III (Fig. 1A) (3). The unsaturated oligosaccharides thus formed are finally degraded by the cytoplasmic exotype alginate lyase A1-IV into monosaccharides (4); these are then nonenzymatically converted to α-keto acids, i.e. 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronic acids (Fig. 1B). An A1-IV homologue Atu3025 is also encoded in the genome of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. A. tumefaciens cells show significant growth on low molecular weight alginate (average molecular weight 1000), and Atu3025 inducibly expressed in the bacterial cells is prerequisite for degradation of the substrate (5). Family PL-15 A1-IV and Atu3025 function in each host cell as the sole enzymes involved in producing unsaturated monosaccharides; thus, they are essential for alginate metabolism. In other bacteria, virus, and abalone, alginate lyases have been shown to release unsaturated oligosaccharides (6–8). No exotype alginate lyase that release monosaccharides has been reported. Although some polysaccharide lyases, such as polygalacturonate lyases (Thermotoga maritima PelA in family PL-1 (9) and Erwinia chrysanthemi PelX in family PL-9 (10)), rhamnogalacturonan lyase (Bacillus subtilis YesX in family PL-11 (11)), xanthan lyase (Bacillus sp. strain GL1 XLY in family PL-8 (12)), and alginate lyases (Chlorella virus vAL-1 (13) and Haliotis discus hannai HdAlex in family PL-14 (8), and A1-IV and Atu3025 in family PL-15), have previously been identified as exotype enzymes. A1-IV and Atu3025 are distinguished clearly from the other enzymes by a specific character; that is, both are processing-type enzymes that release unsaturated monosaccharides from the polysaccharide chain (4, 5).

FIGURE 1.

Alginate degradation by endotype (A) and exotype (B) alginate lyases. Thick arrows indicate the cleavage sites for each enzyme against substrate.

The crystal structures of PLs in 18 families have been determined, and the structure and functional relationships of enzymes such as pectin lyase in family PL-1 (14); pectate lyases in families PL-2, PL-3, and PL-10 (15–17); alginate lyases in families PL-5, PL-7, and PL-14 (13, 18, 19); rhamnogalacturonan lyases in families PL-4 and PL-11 (20, 21); chondroitin lyases in families PL-6 and PL-8 (22); hyaluronan lyases in families PL-8 and PL-16 (23, 24); heparin lyases in families PL-13 and PL-21 (25, 26); and xanthan lyase in family PL-8 (12) have been demonstrated. On the other hand, no structural information on family PL-15 alginate lyases has been accumulated, and the enzyme mechanism for releasing unsaturated monosaccharides from the polysaccharide main chain remains to be clarified. This article deals with the determination of crystal structures of family PL-15 Atu3025 and its complex with unsaturated alginate trisaccharide through x-ray crystallography, and identification of the active site structure responsible for substrate recognition and exolytic reaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Sodium alginate (polymerization degree, around 650; viscosity, 1,000 cp) from Eisenia bicyclis was purchased from Nacalai Tesque. DEAE-Toyopearl 650M was purchased from Tosoh; HiLoad 26/10 Q-Sepharose High Performance, HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200pg, and Superdex Peptide 10/300 GL from GE Healthcare.

Enzyme and Protein Assays

The assay for alginate lyase was conducted as follows. The enzyme was incubated at 30 °C for 5 min in a reaction mixture (1 ml) consisting of 0.05% sodium alginate and 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The reaction mixture was heated at 100 °C for 5 min to terminate the reaction, and the amount of unsaturated uronic acids produced in the reaction mixture was determined by the thiobarbituric acid method (27). In each assay, the enzyme was stable and the reaction products were confirmed to increase proportionally with time and enzyme concentration in the reaction mixture. Enzyme activity was determined by measuring the increase in absorbance at 548 nm, resulting from the condensation of β-formylpyruvic acid with thiobarbituric acid (ϵ = 2.9 × 104/m cm). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to liberate 1 μmol of β-formylpyruvic acid per minute at 30 °C. For site-directed mutants, the enzyme assay was done as follows. To estimate the specific activity of the mutants, a large amount of the enzyme was incubated at 30 °C for 60 min in a reaction mixture (1 ml) consisting of 0.05% unsaturated β-d-mannuronate disaccharide (ΔMM) and 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to degrade 1 μmol of ΔMM/min at 30 °C. Quantification of the residual ΔMM was performed using high performance liquid chromatography. An ÄKTA purifier (GE Healthcare) equipped with a Superdex Peptide 10/300 GL was used for high performance liquid chromatography analysis. Reaction products were eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with 10 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) and detected by measuring the absorbance at 235 nm on the basis of C=C double bonds in the ΔMM. Protein content was determined by the Bradford method (28), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Expression and Purification of Atu3025 and Its Derivative with Selenomethionine

Protein expression and purification of Atu3025 were conducted as described previously (5). The DNA fragment encoding the complete sequence of the Atu3025 gene (GenBank number AE007870) with the original stop codon was ligated with pET21b. Thus, the polypeptide expressed from the resultant plasmid (pET21b/Atu3025) was not fused to the histidine-tagged sequence. An overexpression system for the Atu3025 derivative with selenomethionine (SeMet Atu3025) was also constructed in Escherichia coli cells. Unless specified otherwise, all purification procedures were performed at 0–4 °C. E. coli B834(DE3) cells harboring pET21b/Atu3025 were grown in 6 liters of minimal medium (29) (1.0 liter/flask) implemented with 25 mg of selenomethionine/liter. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 5 min, washed with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), and resuspended in the same buffer. After ultrasonic disruption of cells at 9 kHz for 20 min, the clear solution obtained on centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min was used as the cell extract. After an overnight dialysis against 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mm DTT, the cell extract was applied to a DEAE-Toyopearl 650M column (2.5 × 10 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mm DTT. The absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (0–700 mm) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mm DTT (200 ml), and 4-ml fractions were collected every 4 min. Fractions containing SeMet Atu3025, which were eluted between 300 and 500 mm NaCl, were combined and dialyzed overnight against 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mm DTT. The dialysate was applied to a HiLoad 26/10 Q-Sepharose High Performance column (2.6 × 10 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 300 mm NaCl and 0.5 mm DTT. The absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (300–500 mm) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.5 mm DTT (150 ml), and 4-ml fractions were collected every 1 min. Fractions containing SeMet Atu3025, which were eluted between 380 and 420 mm NaCl, were combined and applied to a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg column (1.6 × 60 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.15 m NaCl and 0.5 mm DTT. The proteins were eluted with the same buffer (120 ml), and 2-ml fractions were collected every 2 min. These two purification steps, such as Q-Sepharose High Performance and Superdex 200 pg, were done by the using ÄKTA purifier at room temperature. Fractions containing SeMet Atu3025 were combined and dialyzed overnight against 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and used as the purified SeMet Atu3025. The purified SeMet Atu3025 had the same N-terminal amino acid sequence as Atu3025, with a calculated molecular mass of 87,871 Da from the predicted amino acid sequence (776 residues).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

To replace Arg199, His311, Tyr365, Trp467, and His531 by Ala, Ala, Phe, Ala, and Ala, respectively, Atu3025 mutants were constructed using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The plasmid pET21b/Atu3025 (5) was used as a PCR template, and the following oligonucleotides were used as primers: R199A, sense 5′-CGTGTCGCCACGCTCTGGGCGCAGATGTATATAGACTGC-3′, and antisense 5′-GCAGTCTATATACATCTGCGCCCAGAGCGTGGCGACACG-3′; H311A, sense 5′-GTCTTTCCCTATGACAGCGCTGCGGTGCGCTCGCTTTC-3′, and antisense 5′-GAAAGCGAGCGCACCGCAGCGCTGTCATAGGGAAAGAC-3′; Y365F, sense 5′-GCGGAAGGTCCGCATTTCTGGATGACCGGCATG-3′, and antisense 5′-CATGCCGGTCATCCAGAAATGCGGACCTTCCGC-3′; W467A, sense 5′-GCCTTTTACAATTACGGCGCGTGGGACCTCAACTTCGACGATC-3′, and antisense 5′-GATCGTCGAAGTTGAGGTCCCACGCGCCGTAATTGTAAAAGGC-3′; H531A, sense 5′-CTTACGGTTCGCTCAGCGCCAGTCACGGCGACCAG-3′, and antisense 5′-CTGGTCGCCGTGACTGGCGCTGAGCGAACCGTAAG-3′ (mutations are underlined). Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing with an automated DNA sequencer (model 377; Applied Biosystems). Expression and purification of the mutants were conducted using the same procedures as for Atu3025.

Crystallization and X-ray Diffraction

Atu3025 (20 mg/ml) was crystallized by sitting-drop vapor diffusion on Linbro tissue culture plates as described previously (30). The condition most suitable for Atu3025 crystallization was determined to be a mixture of 80 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.5), 24% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 4,000, 0.16 m magnesium chloride, and 20% (v/v) glycerol. The SeMet Atu3025 was crystallized under the same condition as the native Atu3025 crystal. A crystal for the site-directed mutant (H531A) in complex with alginate trisaccharide (ΔGGG) was prepared by sitting drop vapor diffusion on Intelli plates (Veritas). The droplet (2 μl) was prepared by mixing 1 μl of the protein solution with 1 μl of the reservoir solution and equilibrated at 20 °C against 0.05 ml of reservoir solution. The H531A/ΔGGG complex crystal appeared through sparse matrix screening using a Crystal Screen Cryo kit from Hampton Research in about six months. The condition most suitable for H531A/ΔGGG crystallization was determined to be a mixture of 85 mm HEPES-Na (pH 7.5), 17% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 4,000, 8.5% (v/v) isopropyl alcohol, 15% (v/v) glycerol, and 10 mm ΔGGG. The crystal on a nylon loop (Hampton Research) was placed directly in a cold nitrogen gas stream at −173 °C, and x-ray diffraction images of the crystal were collected at −173 °C under a nitrogen gas stream with a Jupiter 210 CCD detector and synchrotron radiation of wavelength 1.000 Å at the BL-38B1 station of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan). During data collection for single-wavelength anomalous diffraction analysis using the SeMet Atu3025 crystal, the synchrotron radiation wavelength was adjusted to 0.9792 Å. The wavelength was defined from XAFS measurement of the SeMet Atu3025 crystal. The 240 diffraction images (total 240°) with 1.0° oscillation were collected as a consecutive series of datasets. Diffraction data were processed using the HKL2000 program package (31). Data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Atu3025 | SeMet Atu3025 | H531A/ΔGGG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P1 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 64.2, b = 68.2, c = 108.9 α = 78.3, β = 89.3, γ = 88.6 | a = 107.8, b = 108.1, c = 301.1 | a = 81.8, b = 99.7, c = 109.2 |

| Data collection | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 0.9792 | 1.0000 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 50.0–2.10 (2.17–2.10)a | 50.0–3.40 (3.52–3.40)a | 50.0–2.99 (3.11–2.99)a |

| Total reflections | 260,783 | 341,167 | 77,140 |

| Unique reflections | 104,273 | 49,442 | 18,590 |

| Redundancy | 2.5 (1.2) | 3.8 (3.7) | 4.2 (4.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.7 (88.7) | 95.0 (89.8) | 99.5 (99.9) |

| I/δ (I) | 5.3 (2.3) | 5.2 (4.1) | 11.2 (4.9) |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.8 (24.8) | 12.5 (35.0) | 9.9 (36.1) |

| Refinement | |||

| Final model | |||

| Protein residues | 764, 763 (molecules A, B) | 766 | |

| Water | 1,067 | 62 | |

| Chloride ions | 2 | ||

| Sugar (ΔGGG) | 1 | ||

| Resolution limit (Å) | 40.9–2.11 (2.16–2.11) | 37.9–2.99 (3.07–2.99) | |

| Used reflections | 95,821 (6,080) | 17,479 (1,221) | |

| Completeness (%) | 96.4 (83.6) | 99.0 (94.6) | |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 23.5, 28.7 (molecules A, B) | 37.7 | |

| Water | 33.6 | 24.6 | |

| Chloride ions | 19.0 | ||

| Sugar (ΔGGG) | 48.7 | ||

| R-factor (%) | 18.3 (21.8) | 19.9 (28.9) | |

| Rfree (%) | 22.4 (25.4) | 26.2 (34.1) | |

| Root mean square deviations | |||

| Bond (Å) | 0.007 | 0.008 | |

| Angle (°) | 1.04 | 1.064 | |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Favored regions | 97.1 | 95.3 | |

| Allowed regions | 2.9 | 4.7 | |

a Data on the highest shells are given in parentheses.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The crystal structure of Atu3025 was solved by the single-wavelength anomalous diffraction method using the SeMet Atu3025 crystal. Selenium sites and initial phasing were determined by the SOLVE program (32). Density modifications (solvent flattening and histogram matching) were done using the program RESOLVE (33). The initial model was built to consist of 2,812 amino acid residues without side chains through manual modeling and refinement. The Coot program (34) was used for the modification of the initial model. The 50.0–2.10-Å resolution dataset was truncated with the CCP4 program package (35) and used for subsequent refinement. The H531A/ΔGGG crystal was solved by molecular replacement using the Molrep program in the CCP4 program package with the native Atu3025 structure as a reference model. Initial rigid body refinement and several rounds of restrained refinement against the dataset were done using the Refmac5 program (36). Water molecules were incorporated where the difference in density exceeded 3.0 σ above the mean and the 2Fo − Fc map showed a density of more than 1.0 σ. The structure of the enzyme-sugar complex was refined using the Coot program with the parameter file for gulurononic acid at the PRODRG site. Protein models were superimposed, and their root mean square (r.m.s.) deviations were determined with the LSQKAB program (37), a part of the CCP4 program package. Final model quality was checked with the PROCHECK program (38). Ribbon plots were prepared using the PyMOL program (39). Coordinates used in this work were taken from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) (40).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure Determination and Refined Model Quality

Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The refined model from the Atu3025 crystal includes 1,527 amino acid residues, 1,067 water molecules, two chloride ions for two protein molecules, designated as Atu3025 molecules A and B, in an asymmetric unit. 10 amino acid residues (1MRPSAPAISR10) in molecule A and 11 amino acid residues (1MRPSAPAISRQ11) in molecule B N-terminal, and 2 amino acid residues (775QF776) C-terminal in each molecule could not be assigned in the 2Fo − Fc map possibly due to disorder. The final overall R-factor for the refined model was 18.3% with 95,821 unique reflections within a 40.9–2.11-Å resolution range. The final overall free R-factor calculated with randomly selected 5% reflection was 22.4%. Based on theoretical curves in the plot calculated according to Luzzati (41), the absolute positional error was estimated to be 0.23 Å at a resolution of 2.11 Å. Ramachandran plot analysis (42), in which the stereochemical correctness of the backbone structure is indicated by (ϕ, ψ) torsion angles (43), shows that 97.1% of nonglycine residues are in the favored region and 2.9% are in the allowed regions. Four cis-peptides were observed between Glu27 and Pro28, Asn37 and Pro38, His139 and Pro104, and Tyr349 and Ser350 residues in each molecule.

Overall Structure

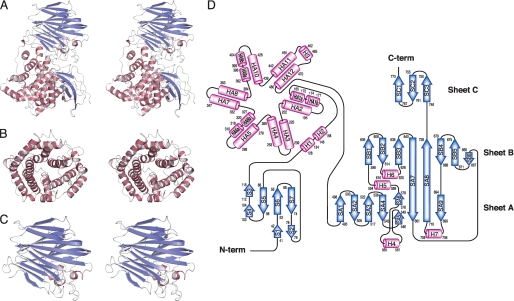

The overall structure (Fig. 2, A–C) and topology of the secondary structure elements (Fig. 2D) indicate that alginate lyase Atu3025 consists of three globular domains: N-terminal small β-sheet domain, central α-domain, and C-terminal β-sheet domain. The N-terminal small β-sheet domain consists of 106 amino acid residues from Gln11 to Ile116 and is composed of two antiparallel β-sheets consisting of seven β-strands (S1 to S7). The central α-domain consists of 364 amino acid residues from Arg128 to Asp491 and is constituted by 15 α-helices (HA1 to HA12 and H1 to H3). The three helices, such as HA1, HA6, and HA9, are divided into two segments, HA1a (amino acid residues 165–172) and HA1b (174–177), HA6a (310–318) and HA6b (320–327), and HA9a (392–396) and HA9b (399–404), respectively. There are one or two additional residues (HA1, Val173; HA6, Val319; and HA9, Thr397 and Gly398) whose oxygen atom has no hydrogen bond with the nitrogen atom of a paired residue. The 12 helices, HA1 to HA12, contribute to the formation of an α6/α6-barrel structure with a deep cleft (Fig. 2, B and D) and are connected by short and long loops in a nearest neighbor, up-and-down pattern. This arrangement is described as a “twist α/α-barrel” with six inner α-helices (HA2, HA4, HA6, HA8, HA10, and HA12), which are oriented in roughly the same direction, and six outer α-helices (HA1, HA3, HA5, HA7, HA9, and HA11) running in the opposite direction. The two helices, H1 and H2, are connected between the N-terminal small β-sheet and α6/α6-barrel domains. The other short helix H3 is adjoined to the long helices. The C-terminal β-sheet domain consists of 279 amino acid residues from Leu495 to Pro773 and is constituted by 18 β-strands (SA1 to SA9, SB1 to SB6, and SC1 to SC3) and four short α-helices (H4 to H7). These β-strands constitute three antiparallel β-sheets (sheet A, SA1-SA9; sheet B, SB1-SB6 and SA7-SA8; and sheet C, SC1-SC3), forming a three-layered β-sheet sandwich structure (Fig. 2, C and D). Helices H4, H6, and H7 are located between strands SA4 and SA5 in sheet A, SB2 and SB3 in sheet B, and SA8 and SA9 in sheet A, respectively. Helix H5 is positioned between strands SA6 in sheet A and SB1 in sheet B.

FIGURE 2.

Structure of Atu3025. A, overall structure (stereodiagram). B, central α-domain (stereodiagram). C, C-terminal β-domain (stereodiagram). D, topology diagram. β-Sheets are shown as blue arrows, and helices are shown as pink cylinders.

Alginate lyases classified into families PL-5, PL-6, PL-7, PL-14, PL-17, PL-18, and PL-20 adopt the α/α-barrel or the β-jelly roll as a basic structural scaffold, demonstrating that the α/α-barrel + anti-parallel β-sheet of family PL-15 Atu3025 is a novel scaffold in the alginate lyases analyzed thus far. Structural homologues of Atu3025 were searched for in the PDB using the DALI program (44). Several proteins such as heparinase II protein (PDB entry 2FUQ, Z = 30.8) (26), xanthan lyase (PDB entry 1X1H, Z = 15.5) (12), and hyaluronate lyase (PDB entry 1LXM, Z = 15.3) (45) were found to exhibit a significant structural homology to overall structure of Atu3025 (Table 2). Because family PL-5 alginate lyase A1-III and family PL-8 and PL-21 chondroitin/heparin lyases are classified into the chondroitin AC/alginate lyase superfamily due to the presence of an α/α-barrel domain in the SCOP data base (46), Atu3025 is regarded as a member of the lyase superfamily.

TABLE 2.

Structure-based homology with Atu3025

| Z score | Description | R.m.s. deviation | LALIa | PDB code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30.8 | Heparinase II protein | 3.6 | 577 | 2FUQ |

| 18.4 | Alginate lyase A1-III | 3.7 | 292 | 3EVH |

| 15.5 | Xanthan lyase | 5.4 | 490 | 1X1H |

| 15.3 | Hyaluronate lyase | 5.4 | 431 | 1LXM |

| 15.2 | Hyaluronate lyase | 5.2 | 446 | 1OJM |

| 15.0 | Chondroitinase AC | 5.0 | 470 | 1HMW |

| 14.8 | Chondroitin AC lyase | 3.6 | 231 | 1RW9 |

| 14.3 | Chondroitin ABC lyase I | 3.6 | 219 | 1HN0 |

| 14.0 | 4-α-Glucanotransferase | 5.9 | 254 | 1K1X |

| 13.9 | Chondroitin sulfate lyase ABC | 6.4 | 504 | 2Q1F |

a Total number of equivalenced residues.

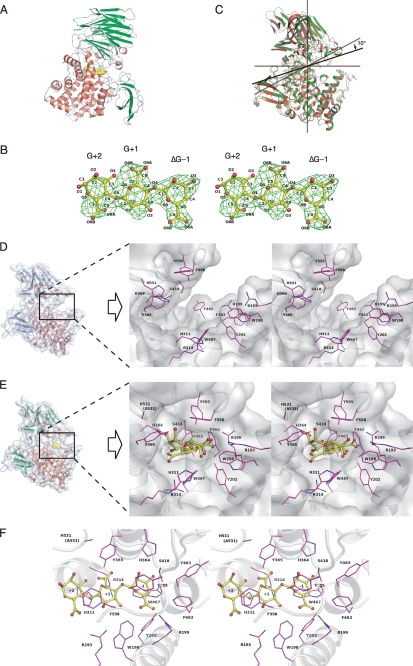

Conformational Change by Substrate Binding

To identify the catalytic residues and structural determinants for the exolytic mode of action in Atu3025, a crystal of H531A/ΔGGG was prepared. His531 comprises a component of the active pocket, and the mutant H531A shows a significantly lower activity than the wild-type enzyme. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1. The crystal structure of H531A/ΔGGG determined at 2.99-Å resolution consists of 766 amino acid residues, which are derived from an Atu3025 monomer, and one ΔGGG molecule in an asymmetric unit. The ΔGGG molecule was bound to the deep pocket between central α/α-barrel and C-terminal β-sheet domains (Fig. 3A). The nonreducing terminal and central residues of ΔGGG are well fitted in the electron density map with average B-factors of 42.0 and 47.4 Å2, whereas the reducing terminal residue are poorly fitted (average B-factor of 55.5 Å2) (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Active site structure of Atu3025. A, overall structure of H531A/ΔGGG. B, electron density of the ΔGGG molecule in the active pocket by the omit map (Fo − Fc) calculated without ΔGGG and countered at 3.0 σ. C, superimposition of ligand-free Atu3025 (red) and H531A/ΔGGG (green). D, surface model and active site structure (inset, stereodiagram) of the ligand-free Atu3025. E, surface model and active site structure (inset, stereodiagram) of H531A/ΔGGG. F, residues in the H531A/ΔGGG structure interacting with the ΔGGG molecule in the active pocket. Amino acid residues and ΔGGG molecule are shown by colored elements: oxygen atom, red, carbon atom, pink in amino acid residues, and yellow in the ΔGGG molecule; nitrogen atom, deep blue. Characters in panel B indicate the saccharide number and its atoms. Characters in panels D–F indicate the subsite and amino acid residue numbers.

The r.m.s. deviation between ligand-free Atu3025 and H531A/ΔGGG complex structures was calculated as 1.59 Å for all residues (764 Cα atoms), indicating that significant conformational changes occur between protein structures with and without ΔGGG. Fig. 3C shows the superimposition of ligand-free Atu3025 and H531A/ΔGGG. The protein structures have been aligned by use of only the central α/α barrel domain (amino acid residues from Arg128 to Asp491). The C-terminal β-sheet domain of Atu3025 can adopt two different conformations through a rigid-body rotation of ∼10°. This hinge bending motion was observed in the plane formed at the interface of the α/α-barrel and C-terminal β-sheet domains. ΔGGG is included in the pocket-like active center, causing the conformational rearrangement (Fig. 3E). Several amino acid residues such as Arg193, Trp198, Arg199, Tyr202, Glu254, His311, Arg314, His364, Tyr365, Ser418, Phe462, Tyr463, Trp467, His531, Tyr555, and Phe558 are arranged around the active pocket. Structure comparison of ligand-free Atu3025 and H531A/ΔGGG demonstrates that the side chain of Phe462 is turned away and interacts with Ser418, which is positioned at the opposite side of the active pocket (Fig. 3, D and E), suggesting that Phe462 plays an important role in forming the pocket. Enzyme flexibility as seen in Atu3025 has been reported in family PL-8 hyaluronate lyase from Streptococcus pneumoniae (47); this flexibility is essential to construct the active center for enzymes with an α/α-barrel + anti-parallel β-sheet topology.

Active Site Structure

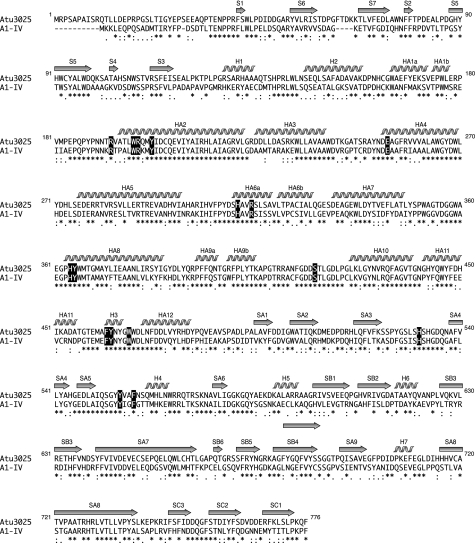

The crystal structure of H531A/ΔGGG revealed the binding mode of the substrate ΔGGG molecule to the active cleft (Fig. 3F). Subsites are labeled so that −n represents the nonreducing terminus and n the reducing terminus, and cleavage occurs between the −1 and +1 sites (48). Atu3025 depolymerizes alginate exolytically, releasing monosaccharides from the nonreducing end of the polymer through a β-elimination reaction. Based on the location of the nonreducing terminus residue of ΔGGG in the deepest spot of the active pocket, the saccharides are considered to be positioned at subsites −1, +1, and +2. Therefore, the constituent guluronic acid residues of ΔGGG are designated as ΔG−1, G+1, and G+2 from the nonreducing end. Several amino acid residues are responsible for binding to ΔGGG (Table 3, Fig. 3F). ΔG−1 is accommodated at subsite −1 through seven hydrogen bonds by four residues, Arg199, Tyr202, His364, and Tyr555, and 26 carbon-carbon (C-C) contacts by six residues, Trp198, Arg199, Ser418, Phe462, Trp467, and Tyr555. Residue Trp467 interacts with the pyranose ring of ΔG−1 through a stacking interaction by 12 C-C contacts. At subsite +1, seven hydrogen bonds by five residues, Glu254, Ser310, His311, Arg314, and Tyr365, and 23 C-C contacts by four residues, Trp198, His311, Tyr365, and Phe558, are formed between G+1 and protein. At subsite +2, G+2, the reducing terminal residue of ΔGGG, is hydrogen bonded to three residues, Ser310, His311, and Ser530, and there are 14 C-C contacts by three residues, Ser310, His311, and Phe558. Phe558 is partially parallel to the pyranose ring of both G+1 and G+2, indicating that the residue undergoes a partially stacking interaction with the sugar ring of these two residues. Positively charged residues such as Arg199 and Arg314 are supposed to be crucial for binding acidic polysaccharides and/or neutralizing the negative charge of the carboxyl groups in ΔG−1 and G+1. A multiple sequence alignment of family PL-15 exotype alginate lyases using the ClustalW program is shown in Fig. 4. Atu3025 shows a significant sequence identity of 55.0% with A1-IV from Sphingomonas sp. A1. The residues outlined above are completely conserved between the two.

TABLE 3.

Interactions between Atu3025 and ΔGGG

FIGURE 4.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of family PL-15 alginate lyase. Atu3025, alginate lyase from A. tumefaciens strain C58 (GenPept accession number AAL43841); A1-IV, alginate lyase from Sphingomonas sp. strain A1 (GenPept accession number BAB03319). Amino acid sequences were aligned using the ClustalW program. Identical and similar amino acid residues in these alginate lyases are denoted by asterisks and dots, respectively. Secondary structure elements of Atu3025 are as shown above. Amino acid residues interacting with ΔGGG are highlighted in black.

Structural Insights into the Catalytic Reaction and Exolytic Mode of Action

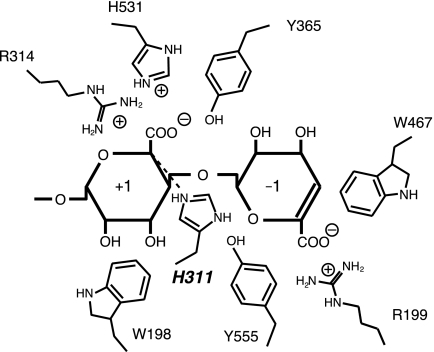

The catalytic reaction of polysaccharide lyases is divided into three steps as follows (49): (i) positively charged residues stabilize or neutralize the negative charge on the C-6 carboxylate anion, (ii) a general base catalyst abstracts the proton from C-5 of the uronic acid residue, and (iii) a general acid catalyst donates the proton to the glycoside bond to be cleaved. To identify the role of Atu3025 residues in the active site, we constructed the mutants, R199A, H311A, Y365F, W467A, and H531A, in which Arg199, His311, Tyr365, Trp467, and His531 were replaced by Ala, Ala, Phe, Ala, and Ala, respectively. These residues for mutation were supposed to play an important role in recognizing the acidic polysaccharide and/or catalyzing the enzyme reaction based on the structure of H531A/ΔGGG. The mutants were overexpressed in E. coli cells and purified to homogeneity. Their specific activities were determined as follows (Table 4). In all mutants, especially H311A and W467A, the enzyme activity significantly decreased. Various amino acid residues are reported to act as a catalytic base or acid in PL families. Although Arg in families PL-1 and PL-10 (17), Lys in family PL-9 (50), Tyr in families PL-5 (19), and PL-8 (22), and His in family PL-7 (18) function as a catalytic base, Tyr in families PL-5 (19), PL-7 (18), and PL-8 (22) function as a catalytic acid. In the family PL-5 alginate lyase A1-III from Sphingmonas sp. strain A1, Tyr246 is considered to act as both a catalytic base and acid (19). On the other hand, the family PL-7 alginate lyase A1-II′ from Sphingmonas sp. strain A1 adopts His191 and Tyr284 as the catalytic base and acid (18), respectively. These catalytic His and Tyr residues well conserved in families PL-5 and PL-7 correspond to His311 and Tyr365 in Atu3025, respectively. Based on the active site structure of H531A/ΔGGG (Fig. 3F), the distance between His311 and C5 of G+1 was calculated as 3.4 Å, and between Tyr365 and O4 of G+1 was less than 4.0 Å. Judging from the significant decrease in the specific activity of H311A and Y365F (Table 4), it is plausible that His311 and Tyr365 function as a catalytic base and acid, respectively (Fig. 5), as seen in A1-II′ (18). Tyr555 is also a candidate for a catalytic acid because the distance between Tyr555 and O4 of G+1 was determined as 4.0 Å (Fig. 5), although the Tyr residue is not conserved in family PL-15 alginate lyases (Atu3025, A1-IV, and A1-IV′), so far characterized. His531 is located close enough to interact with the carbohydrate group of G+1, when the residue retains the similar side chain conformation as in the ligand-free Atu3025 (Fig. 3D). Due to this structural feature and low activity of H531A (Table 4), His531 is supposed to play a major role in stabilizing or neutralizing the negative charge on the carboxylate anion of G+1 (Fig. 5). The reduced activity of R199A indicates that Arg199 also functions as a stabilizer on the carboxyl group of ΔG-1 as described above. The intrinsic function of each possible catalytic residue should be analyzed through structure determination of the enzyme and substrate complex at higher resolution.

TABLE 4.

Specific activity of wild-type and Atu3025 mutants

| Enzyme | Specific activitya | Relative activity |

|---|---|---|

| milliunits/mg | % | |

| Wild-type | 1,140 | 100 |

| R199A | 49 | 4.3 |

| H311Ab | ||

| Y365F | 3.4 | 0.30 |

| W467A | 0.12 | 0.011 |

| H531A | 5.1 | 0.45 |

a The value of wild-type is taken as 100%.

b The activity of the H311A mutant is too weak to determine the specific activity.

FIGURE 5.

Catalytic center in Atu3025. The residues surrounding subsites −1 and +1 are represented schematically.

Unlike other polysaccharide lyases, family PL-15 enzymes such as Atu3025 and A1-IV can release unsaturated monosaccharides from polysaccharide. The crystal structure of H531A/ΔGGG shows a part of the structural determinants for the exolytic mechanism. The distinguishing characteristic of Atu3025, namely a pocket-like structure, is observed in the environment surrounding subsite −1. The pocket is formed by two structural determinants, i.e. a conformational change at the interface between the central and C-terminal domains and the presence of a short α-helix H3 (Fig. 3, D and E). Tyr555 and Phe558 in the C-terminal β-sheet domain and Phe462 and Trp467 around H3 are actually involved in accommodating the substrate (Table 3). At subsite −1, seven hydrogen bonds and 26 C-C contacts are formed between the enzyme and sugar. In particular, Trp467 forms 12 C-C contacts with ΔG-1 and the mutant W467A showed the significant reduction in the specific activity compared with the wild-type (Table 4), indicating that the residue is essential for recognition of a nonreducing terminal residue of the substrate. This pocket-like structure is not observed in other polysaccharide lyases, even in the family PL-8 and PL-20 enzymes with the α/α-barrel + anti-parallel β-sheet as a basic scaffold. In family PL-8 hyaluronate lyase from S. pneumoniae (47), a pocket-like structure is absent in its active site although the conformational change caused by substrate binding has been reported. Some polysaccharide lyases such as rhamnogalacturonan lyase YesX from B. subtilis and alginate lyase vAL-1 from Chorella virus have been reported to release the unsaturated disaccharide exolytically. Their previous crystallographic studies demonstrated that the steric hindrance at one end of the active cleft and the sugar-binding affinity level in subsites are crucial for the exolytic mode of action of YesX (51) and vAL-1 (13), respectively. Therefore, it is reasonable to presume that the pocket-like structure is a characteristic of the family PL-15 exotype alginate lyases, which release unsaturated monosaccharides as a sole product, and is essential for recognizing the nonreducing terminal residues of substrate. Based on the above described results, Atu3025 probably adopts the five-step cycle to exhibit the exolytic mode of action as follows: (i) alginate approaches the active site of the “open form” enzyme, (ii) the terminal saccharide of the polymer is accommodated at subsite −1 through the conformational modulation (open/close), (iii) the glycosidic linkage is cleaved in the “closed form,” (iv) the enzyme takes the open form to release the product, and (v) the remaining substrate slides along the active site through the conformational modulation (open/close).

Conclusions

This is, to our knowledge, the first report on the structural determination of the family PL-15 enzyme and establishment of a new structural category in alginate lyases involving an α/α-barrel + anti-parallel β-sheet-fold. The active site structure of H531A/ΔGGG and the subsequent site-directed mutational analysis suggest that His311 and Tyr365 function as a catalytic base and acid, respectively. Additionally, a pocket-like structure of Atu3025, which is formed by the conformational change at the interface between the central and C-terminal domains, is essential for the exolytic mode of action involved in releasing unsaturated monosaccharides from the polysaccharide main chain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. K. Hasegawa and S. Baba of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) for their kind help in data collection. Diffraction data for crystals were collected at the BL-38B1 station of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan) with the approval of JASRI.

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K. M. and W. H.), the Targeted Proteins Research Program (to W. H.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, and Research Fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (to A. O.) and the program (to K. M.) for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Bioscience (PROBRAIN) in Japan.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3A0O and 3AFL) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- PL

- polysaccharide lyase

- ΔGGG

- unsaturated alginate trisaccharide (4-deoxy-l-erythro-hex-4-enepyranosyluronate-guluronate-guluronic acid)

- H531A/ΔGGG

- crystal structure of H531A in complex with ΔGGG

- r.m.s.

- root mean square

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- C-C

- carbon-carbon

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- SeMet

- selenomethionine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong T. Y., Preston L. A., Schiller N. L. (2000) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 289–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon H.-J., Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Okamoto M., Mikami B., Murata K. (2000) Protein Expr. Purif. 19, 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Momma K., Kawai S., Murata K. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 4572–4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochiai A., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2006) Res. Microbiol. 157, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gimmestad M., Ertesvåg H., Heggeset T. M., Aarstad O., Svanem B. I., Valla S. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 4845–4853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suda K., Tanji Y., Hori K., Unno H. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180, 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suzuki H., Suzuki K., Inoue A., Ojima T. (2006) Carbohydr. Res. 341, 1809–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kluskens L. D., van Alebeek G. J., Voragen A. G., de Vos W. M., van der Oost J. (2003) Biochem. J. 370, 651–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks A. D., He S. Y., Gold S., Keen N. T., Collmer A., Hutcheson S. W. (1990) J. Bacteriol. 172, 6950–6958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochiai A., Itoh T., Kawamata A., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2007) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 3803–3813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruyama Y., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 781–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogura K., Yamasaki M., Yamada T., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35572–35579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayans O., Scott M., Connerton I., Gravesen T., Benen J., Visser J., Pickersgill R., Jenkins J. (1997) Structure 5, 677–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott D. W., Boraston A. B. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35328–35336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creze C., Castang S., Derivery E., Haser R., Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat N., Shevchik V. E., Gouet P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18260–18268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charnock S. J., Brown I. E., Turkenburg J. P., Black G. W., Davies G. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12067–12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogura K., Yamasaki M., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 380, 373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon H.-J., Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Murata K., Mikami B. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 307, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonough M. A., Kadirvelraj R., Harris P., Poulsen J. C., Larsen S. (2004) FEBS Lett. 565, 188–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochiai A., Itoh T., Maruyama Y., Kawamata A., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 37134–37145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lunin V. V., Li Y., Linhardt R. J., Miyazono H., Kyogashima M., Kaneko T., Bell A. W., Cygler M. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 367–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rigden D. J., Jedrzejas M. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50596–50606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mishra P., Prem Kumar R., Ethayathulla A. S., Singh N., Sharma S., Perbandt M., Betzel C., Kaur P., Srinivasan A., Bhakuni V., Singh T. P. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 3392–3402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han Y. H., Garron M. L., Kim H. Y., Kim W. S., Zhang Z., Ryu K. S., Shaya D., Xiao Z., Cheong C., Kim Y. S., Linhardt R. J., Jeon Y. H., Cygler M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34019–34027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaya D., Tocilj A., Li Y., Myette J., Venkataraman G., Sasisekharan R., Cygler M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15525–15535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weissbach A., Hurwitz J. (1959) J. Biol. Chem. 234, 705–709 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doublié S., Carter C. W. J. (1992) Crystallization of Nucleic Acids and Proteins: A Practical Approach, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ochiai A., Yamasaki M., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 62, 486–488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terwilliger T. C. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56, 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collaborative. (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kabsch W. (1976) Acta Crystallogr. A 32, 922–923 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeLano W. L. (2004) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., Bourne P. E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luzzati V. (1952) Acta Crystallogr. 5, 802–810 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lovell S. C., Davis I. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, de Bakker P. I., Word J. M., Prisant M. G., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2003) Proteins 50, 437–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramachandran G. N., Sasisekharan V. (1968) Adv. Protein Chem. 23, 283–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holm L., Sander C. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 233, 123–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mello L. V., De Groot B. L., Li S., Jedrzejas M. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36678–36688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murzin A. G., Brenner S. E., Hubbard T., Chothia C. (1995) J. Mol. Biol. 247, 536–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jedrzejas M. J., Mello L. V., de Groot B. L., Li S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28287–28297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davies G. J., Wilson K. S., Henrissat B. (1997) Biochem. J. 321, 557–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linker A., Meyer K., Hoffman P. (1956) J. Biol. Chem. 219, 13–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins J., Shevchik V. E., Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat N., Pickersgill R. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9139–9145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ochiai A., Itoh T., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10181–10189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]