Abstract

We have identified an operon and characterized the functions of two genes from the severe food-poisoning bacterium, Bacillus cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98, that are involved in the synthesis of a unique UDP-sugar, UDP-2-acetamido-2-deoxyxylose (UDP-N-acetyl-xylosamine, UDP-XylNAc). UGlcNAcDH encodes a UDP-N-acetyl-glucosamine 6-dehydrogenase, converting UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to UDP-N-acetyl-glucosaminuronic acid (UDP-GlcNAcA). The second gene in the operon, UXNAcS, encodes a distinct decarboxylase not previously described in the literature, which catalyzes the formation of UDP-XylNAc from UDP-GlcNAcA in the presence of exogenous NAD+. UXNAcS is specific and cannot utilize UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-galacturonic acid as substrates. UXNAcS is active as a dimer with catalytic efficiency of 7 mm−1 s−1. The activity of UXNAcS is completely abolished by NADH but unaffected by UDP-xylose. A real-time NMR-based assay showed unambiguously the dual enzymatic conversions of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-GlcNAcA and subsequently to UDP-XylNAc. From the analyses of all publicly available sequenced genomes, it appears that UXNAcS is restricted to pathogenic Bacillus species, including Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus thuringiensis. The identification of UXNAcS provides insight into the formation of UDP-XylNAc. Understanding the metabolic pathways involved in the utilization of this amino-sugar may allow the development of drugs to combat and eradicate the disease.

Keywords: Bacterial Metabolism, Carbohydrate Complex, Enzyme Catalysis, Extracellular Matrix, Glycosaminoglycan, NMR, Bacillus cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98

Introduction

A food poisoning outbreak in France in 1998 led to the isolation of a new strain of Bacillus cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98 (1). This rod-shaped Gram-positive bacterium causes a disease that initially produces emetic (nausea and vomiting)-like symptoms, and/or in more severe cases produces a diarrheal form that causes abdominal cramps and diarrhea (2). Similar to its close relatives, the notorious human pathogen Bacillus anthracis and the insecticidal Bacillus thuringiensis, the B. cereus strain can form spores. Due to its cell surface, a spore can survive harsh conditions (e.g. soil and air), and when the environment becomes appropriate, it will germinate, resulting in a vegetative cell that can produce emetic toxin and different enterotoxins (3). The cell surfaces of many pathogenic bacteria are composed of diverse and complex carbohydrate structures, some of which are known virulence factors. Indeed, different B. cereus peptidoglycans and glycoproteins were isolated, and some were reported to play a role in spore formation and infection (3–5). It is also clear, however, that among those different types of Bacillus glycans, many are not yet fully characterized. Regardless, compared with the limited knowledge of these glycan structures, the pathways leading to their biosyntheses are still elusive. To identify such metabolic pathways, we initially decided to look for putative genes encoding enzymes involved in the synthesis of glycan precursors (i.e. nucleotide-sugars).

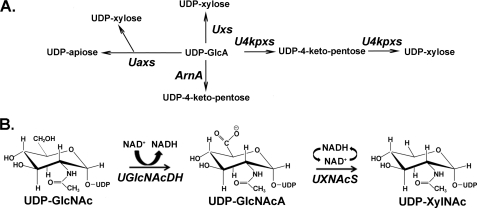

Different UDP-GlcA2 decarboxylases with distinct functions exist in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes (Fig. 1A). UDP-xylose synthase (Uxs) from animals (6), plants (7), fungi (8), and bacteria,3 for example, decarboxylates UDP-GlcA into UDP-xylose via an enzyme-bound NAD+. A different decarboxylase in plants, UDP-apiose/UDP-xylose synthase (Uaxs), converts UDP-GlcA in the presence of NAD+ to both UDP-apiose and UDP-xylose (9). A bifunctional decarboxylase, UDP-4-ketopentose/UDP-xylose synthase (U4kpxs) from Ralstonia solanacearum strain GMI1000 converts UDP-GlcA and NAD+ to UDP-4-ketopentose and then, in the presence of NADH, turns UDP-4-ketopentose to UDP-xylose (10). ArnA is also a decarboxylase, identified in Escherichia coli, and it converts UDP-GlcA and NAD+ to UDP-4-ketopentose and NADH (11).

FIGURE 1.

NDP-uronate sugar decarboxylases in eukaryote and prokaryote. A, in animals, plants, and some fungi and bacteria, UDP-GlcA is converted to UDP-xylose by Uxs. Plants also have a bifunctional Uaxs that can inter-convert UDP-GlcA to UDP-apiose and UDP-xylose. In some bacteria, UDP-GlcA can be converted into UDP-4-ketopentose in the presence of ArnA. Other bacteria may have a bifunctional U4kpxs that first converts UDP-GlcA to UDP-4-ketopentose and subsequently forms UDP-xylose from UDP-4-ketopentose, albeit at a lower rate compared with the first activity. B, the biosynthesis of UDP-XylNAc in B. cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98. In the presence of UGlcNAcDH, UDP-GlcNAc was first converted into UDP-GlcNAcA, which is further decarboxylated into UDP-XylNAc with the activity of UXNAcS. Similar operon organization is found in other Bacillus species, such as B. anthracis and B. thuringiensis.

The above enzymes supply sugar precursors for the biosynthesis of various glycans, including proteoglycans in human and animals (6, 12, 13), glucuronoxylomannan in the pathogenic fungus Cryprtococcus neofromans (14–16), diverse plant polysaccharides, such as xylan and xyloglucan (17, 18), and different types of lipopolysaccharides in bacteria (11). We are interested in studying the evolution of nucleotide-sugar biosynthetic pathways across all species, as a way to understand the richness of diverse glycans and to evaluate how this diversity provides the specific organism an advantage for ecological adaptation. Here, we report the first identification and characterization of two genes (UGlcNAcDH and UXNAcS) involved in the biosynthesis of UDP-2-acetimido-2-deoxy-α-d-xylopyranoside (UDP-XylNAc) (Fig. 1B) from B. cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98. The identification of these enzymes provides insight related to the formation of a new UDP-amino sugar and means to explore their roles within the life cycle of this human pathogen. Hopefully, this may lead to the eradication of the disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning of UGlcNAcDH and UXNAcS from B. cereus Subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98

Genomic DNA isolated from B. cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98 was used as templates to clone the coding sequences of two genes in an operon predicted to be involved in nucleotide-sugars syntheses. The genes herein named UGlcNAcDH (UDP-GlcNAc 6-dehydrogenase) and UXNAcS (UDP-XylNAc synthase) were amplified by PCR using 1 unit of proofreading Platinum TaqDNA polymerase high fidelity (Invitrogen), 200 μm dNTPs, and a 0.2 μm concentration of following primers: 5′-CCATGGAAAAAGAGAAAGGAGAAG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCAAGCTTTGCACTCACCTTCTTTAG-3′ for UGlcNAcDH; 5′-CCATGGCTAAGAAACGTTGTTTGATTACAGGTG-3′ and 5′-AAGCTTATCATTCTCTATTTCACGAAACCAC-3′ for UXNAcS. The PCR products were isolated from agarose gel and cloned to generate plasmids pCR4:BcUGlcNAcDH#1 and pGEM-T:BcUXNAcS#1, respectively. The Nco1-HindIII fragments of UGlcNAcDH (1273 bp) and UXNAcS (970 bp) were cloned into an E. coli expression vector to form pET28b:BcUGlcNAcDH#1 and pET28b:BcUXNAcS#1, respectively. The recombinant enzymes were designed to have a six-histidine extension at their C terminus to facilitate affinity purification.

Protein Expression and Purification

E. coli cells containing pET28b:BcUGlcNAcDH#1, pET28b:BcUXNAcS#1, or an empty vector control (pET28b) were cultured for 16 h at 37 °C in 20 ml of LB medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml). A portion (7 ml) of the cultured cells was transferred into fresh LB liquid medium (250 ml) supplemented with the same antibiotics, and the cells were then grown at 37 °C at 250 rpm until the cell density reached A600 = 0.8. The cultures were then transferred to 30 °C, and gene expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mm. After 4 h of growth while shaking (250 rpm), the cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C) and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 ml 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, and 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Ammonium sulfate (50 mm) was also included for cells harboring UGlcNAcDH or empty vector. Cells were lysed in an ice bath by 24 sonication cycles (10-s pulse, 20-s rest) using a Misonix S-4000 sonicator (Misonix Inc., Farmingdale, NY) equipped with a one-eighth-inch microtip probe. The lysed cells were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 6,000 × g, and the supernatant was supplemented with 1 mm DTT and centrifuged again (30 min at 20,000 × g). The resulting supernatant (termed S20) was recovered and kept at −20 °C.

His-tagged proteins were purified over a Ni2+-Sepharose fast flow column (2 ml of resin (GE Healthcare) packed in a 10-mm inner diameter × 150-mm-long column). The column was pre-equilibrated with 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 0.1 m NaCl. The bound His-tagged protein was eluted with the same buffer containing increasing concentrations of imidazole. The fractions containing enzyme activity were pooled, supplemented with 1 mm DTT and 10% (v/v) glycerol, and dialyzed using 6,000–8,000 molecular weight cut-off (Spectrum Laboratories) tubing at 4 °C three times for 30 min each with 800 ml of dialysis buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 0.1 m NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mm DTT). The purification and dialysis of UGlcNAcDH included 50 mm ammonia sulfate in all of the buffers. The purified and dialyzed UXNAcS and UGlcNAcDH were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in aliquots at −80 °C. Proteins extracted from E. coli cells expressing empty vector were passed via the same nickel column, and fractions eluted with imidazole were collected and served as controls in enzyme assays and SDS-PAGE analyses. The concentration of protein was determined using the Bradford reagent with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The estimated molecular weight of the active UXNAcS was determined by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex-200 column (5).

UGlcNAcDH and UXNAcS Enzyme Assays and HPLC Analysis

The UGlcNAcDH assays were conducted in a total volume of 50 μl consisting of 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.6), 1 mm NAD+, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAc (50 nmol), 50 mm ammonia sulfate, and a 2-μl S20 fraction or purified recombinant UGlcNAcDH (1.5 μg).

The UXNAcS standard reaction assay, unless otherwise indicated, consisted of 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 8.2, 0.4 mm NAD+, 0.4 mm UDP-GlcNAcA (20 nmol), and 1.5 μg recombinant UXNAcS in final volume of 50 μl. Following incubation at 37 °C for up to 30 min for UGlcNAcDH and 15 min for UXNAcS, assays were terminated by heating (45 s at 80–100 °C). Chloroform (50 μl) was added, and after vortexing (30 s) and centrifugation (12,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature), the entire upper aqueous phase was collected and subjected to chromatography on a Q15 anion exchange column (4.6-mm inner diameter × 250-mm-long; Amersham Biosciences) using an Agilent Series 1100 HPLC system equipped with an autosampler, diode array detector, and ChemStation software version B.04.02. After sample injection, the Q15 column was washed at 1 ml/min for 5 min with 20 mm ammonium formate, and subsequently nucleotides were eluted with a linear 20–600 mm ammonium formate gradient formed over 25 min. Nucleotides were detected by their UV absorbance. The maximum absorbance values for UDP-sugars, NAD+, and NADH were 261, 259, and 259/340 nm, respectively, in ammonium formate. The peak area of analytes was determined based on standard calibration curves. The peak corresponding to UDP-GlcNAcA (eluted at 21.4 min) or to UDP-XylNAc (eluted at 15.1 min) was collected, lyophilized, resuspended in D2O, and further analyzed by NMR.

MALDI-MS Analysis

Negative ion MALDI mass spectra were recorded using a Microflex LT mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany). Aqueous samples (1 μl of 1 mm UDP-GlcNAcA or UDP-XylNAc) were mixed with an equal volume of matrix solution (1 μg/μl 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in 50% methanol) and dried on the plate. Spectra from 500 laser (N2, 337 nm) shots were summed to generate a mass spectrum.

1H NMR Analyses

One-dimensional proton NMR spectrum of the HPLC-purified UDP-GlcNAcA peak (lyophilized and resuspended in 250 μl of D2O buffered with 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH/pD 7.6) was collected at 37 °C using a Varian DirectDriveTM 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe.

The one-dimensional proton and two-dimensional HSQC NMR spectra of the HPLC-purified UDP-XylNAc peak (lyophilized and resuspended in 250 μl of D2O buffered with 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH/pD 8.2) were collected at 25 °C using a Varian DirectDriveTM 900-MHz spectrometer. The HSQC was collected with a carbon spectral width of 80 ppm, centered at 80.1 ppm, and with 64 points of 48 transients each.

The 250-μl real-time 1H NMR-based enzymatic reactions were performed at 37 °C in a final mixture of D2O/H2O (1:9, v/v). The UGlcNAcDH assay consists of 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH/pD 7.6, 1 mm NAD+, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAc and 10 μl of S20 UGlcNAcDH. The UXNAcS reaction contains 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH/pD 8.2, 1 mm NAD+, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAcA, and 7.5 μg of recombinant UXNAcS. The dual enzyme assay was performed in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH/pD 7.6, supplemented with 2 mm NAD+, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAc, 50 mm ammonia sulfate, 20 μl of S20 UGlcNAcDH, and 3 μg of recombinant UXNAcS. Real-time 1H NMR spectra were obtained using the Varian DirectDriveTM 600-MHz spectrometer. Data acquisition was started ∼3 min after the addition of enzyme in order to optimize the spectrometer. Sequential one-dimensional proton spectra with presaturation of the water resonance were acquired over the course of the enzymatic reaction. All NMR spectra were referenced to the resonance of 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate.

Synthesis of UDP-GlcNAcA

UDP-GlcNAcA was produced in a total volume of 5 ml consisting of 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.6, 1 mm NAD+, 1.5 mm UDP-GlcNAc, and 200 μl of the S20 fraction of UGlcNAcDH. Reactions were kept at 37 °C for up to 2 h and terminated by heat (2 min at 80–100 °C) and, after chloroform extraction, were injected into Q15-HPLC column. The peak corresponding to UDP-GlcNAcA was collected, lyophilized, and resuspended in H2O, and an aliquot was reanalyzed by HPLC and 600-MHz 1H NMR to check its identity and purity. The amount of UDP-GlcNAcA produced was calculated by comparing the high pressure liquid chromatogram peak area with calibration curves of standards (UDP-Glc and UDP-GlcA).

Characterization and Kinetic Analyses of Recombinant UXNAcS

The enzyme activity was tested in a variety of buffers, at different temperatures, or with different potential inhibitors. For optimal pH experiments, 1.5 μg of recombinant enzyme was first mixed with 50 mm of each individual buffer (Tris-HCl or sodium phosphate). NAD+ (0.4 mm) and UDP-GlcNAcA (0.4 mm) were then added, and after a 15-min incubation at 37 °C, the amount of UDP-XylNAc formed was determined by HPLC. Inhibition assays were performed by first mixing the enzyme and sodium phosphate buffer with various additives (e.g. nucleotides) on ice for 10 min. UDP-GlcNAcA and NAD+ (0.4 mm each) were then added. After 15 min at 37 °C, the amount of UDP-XylNAc formed was calculated from the high pressure liquid chromatogram. For the optimal temperature experiments, assays were performed under standard conditions, except that reactions were incubated at different temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, the activities were terminated, and the amount of UDP-XylNAc produced was measured by HPLC.

The catalytic activity of UXNAcS was determined at 37 °C for 8 min in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 8.2, with variable concentrations of UDP-GlcNAcA (0.08–1 mm), 1 mm NAD+, and 0.8 μg of protein. The reciprocal initial velocity was plotted against the reciprocal UDP-GlcNAcA concentration according to Lineweaver and Burk to calculate Km value. Enzyme kinetics was linear with respect to the reaction time and to the protein amount.

RESULTS

Identification of UXNAcS and UGlcNAcDH in B. cereus Subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98

Glycan diversity can be generated by the ability of an organism to 1) synthesize new and different types of NDP-sugars; 2) attach the sugar to different molecules in a specific linkage and configuration; 3) modify the glycan with different acetyl, methyl, or amino residues; and 4) link the oligosaccharides to specific lipid, protein molecules, or large capsule of polysaccharides. A major obstacle in studying the metabolic pathways and diversity of glycans across species, especially with pathogenic microbes, is the need to work with live infectious organisms. The available genomes of various species thus provide an opportunity to explore novel genes involved in glycan metabolic pathways as a way to study glycan diversity.

The characteristic signatures of proteins belonging to the large family of short chain dehydrogenase/reductase, such as UDP-GlcA 4-epimerase (19), TDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratse (20, 21), and UDP-GlcA decarboxylase (8, 10), are the GXXGXXG motif for cofactor NAD+ binding (22), and the catalytic triad SYK amino acids commonly found in the SE and YXXXK motifs at the catalytic pocket (23). To identify new enzyme activities belonging to the large short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family, we first did a BLAST search of known proteins against various protein databases. Selected bacterial candidate proteins were further re-examined by 1) their sequence identities to other proteins and 2) analyses of the genes in the operon in which they were found.

BLAST analysis using AtUxs3 (AF387789) led to the identification of a gene in the B. cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98 chromosome, encoding a protein (we later named it UXNAcS) that shared relatively low amino acid sequence identity (supplemental Fig. S1) with known decarboxylases: 32% identity to Sinorhizobium SmUxs1 (GU062741), and 29% identity to the Ralstonia RsU4kpxs (GQ369438). The operon containing UXNAcS also consists of a gene encoding a putative UDP/GDP-sugar dehydrogenase (that we later named UGlcNAcDH). To validate our approach and to identify the functions of both enzymes, their genes were cloned and expressed in E. coli, and the function of the individual recombinant enzyme was studied.

UGlcNAcDH Encodes Active UDP-GlcNAc 6-Dehydrogenase

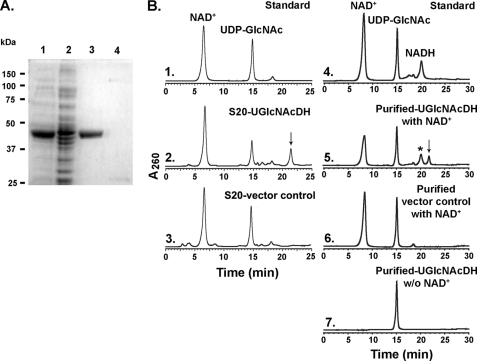

Compared with control, a highly expressed recombinant protein band (47 kDa) was isolated and purified from E. coli cells expressing UGlcNAcDH (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 3). Preliminary HPLC-based assays revealed that the enzyme could not use UDP-glucose as a substrate. However, the recombinant B. cereus enzyme did convert NAD+ and UDP-GlcNAc to NADH (Fig. 2B, panel 5, asterisk) and a new UDP-sugar that eluted from the column at 21.4 min (Fig. 2B, panel 5, arrow). The identity of NADH was confirmed by its dual UV absorbance (259 and 340 nm) and its HPLC retention time when compared with the standard. The peak (21.4 min) was collected and analyzed by MALDI-MS and had a mass of 621.2 (supplemental Fig. S2, panel 1), which would be expected for a UDP-hexo-N-acetylamino-uronic acid. Further analysis of the eluted peak using proton NMR (Fig. 3) provided chemical shifts that are consistent with UDP-GlcNAcA (supplemental Table S1). We thus proposed that this Bacillus gene is active as UDP-GlcNAc 6-dehydrogenase; hence its name UGlcNAcDH. The Bacillus UGlcNAcDH is a very specific dehydrogenase, and in our analyses, no activity was observed with UDP-glucose, UDP-galactose, and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine as substrates (data not shown). HPLC peak integration indicates that the dehydrogenase requires around 2 mol of NAD+ to convert 1 mol of UDP-GlcNAc into 1 mol of UDP-GlcNAcA and 2 mol of NADH.

FIGURE 2.

Expression and characterization of recombinant UGlcNAcDH. A, SDS-PAGE of total soluble protein isolated from E. coli cells expressing UGlcNAcDH (lane 1) or control empty vector (lane 2) and of nickel column-purified fractions (lane 3, UGlcNAcDH; lane 4, control). B, high pressure liquid chromatogram of UGlcNAcDH enzyme reaction. Purified recombinant UGlcNAcDH was incubated with UDP-GlcNAc in the presence (panel 5), or absence (panel 7) of exogenous NAD+. As a control, the corresponding column-purified protein isolated from cells expressing control empty vector was incubated with UDP-GlcNAc and NAD+ (panel 6). Activity of total protein isolated from cells expressing recombinant UGlcNAcDH or vector control is shown in panel 2 and 3, respectively. The reaction products were separated on a Q15 column, and the UDP-sugar peak (marked by arrow, in panels 2 and 5) were collected and analyzed by MALDI-MS and NMR.

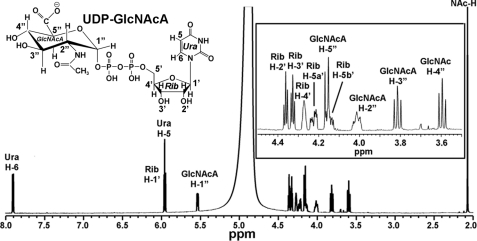

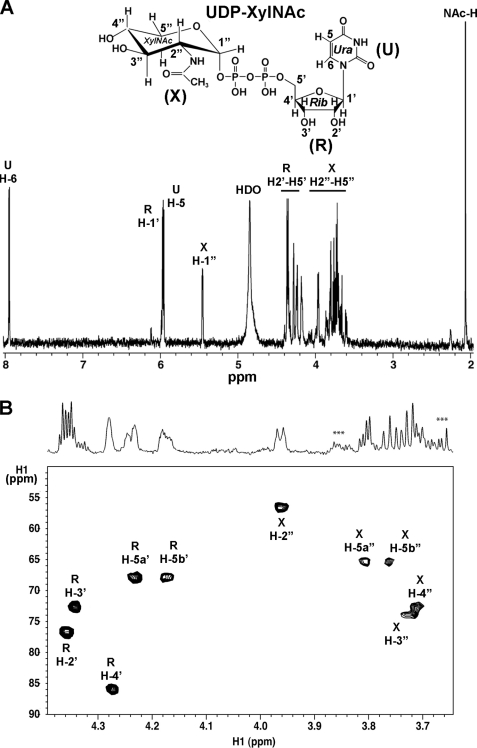

FIGURE 3.

1H NMR analysis of the UGlcNAcDH enzymatic product, UDP-GlcNAcA. The enzymatic product (Fig. 2B, panel 5, marked by an arrow) was collected and analyzed by NMR at 37 °C. One-dimensional 600-MHz NMR spectrum of the product is shown. The location for each proton residue on the spectrum is indicated; the positions of protons on the uracil (Ura) ring are indicated by H, the ribose (Rib) protons by H′, the GlcNAcA protons by H″, and the C″-2-linked acetamido by NAc-H. Inset, an expansion of the one-dimensional NMR spectrum from 3.5 to 4.5 ppm.

Our initial enzymatic characterization of the Bacillus UGlcNAcDH indicates that the enzyme has identical activity with a previously described UGlcNAcDH (WpbA) isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (24). Therefore, we decided to concentrate our effort on the characterization of the other Bacillus gene product (UXNAcS) in that operon that has no homologous protein in Pseudomonas.

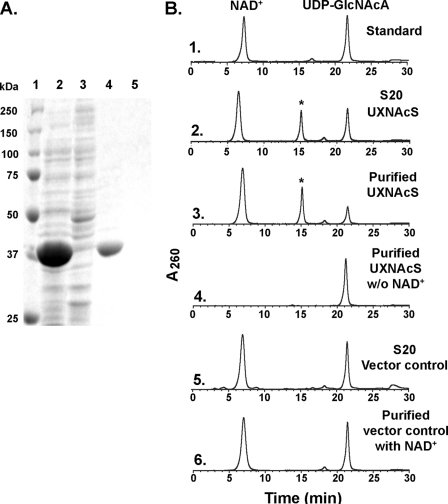

Identification of a New Enzyme Activity, UDP-XylNAc Synthase

As shown in Fig. 4A, the recombinant Bacillus UXNAcS (37 kDa) was expressed in E. coli and subsequently column-purified. Initial analyses in the presence of exogenous NAD+ with different commercially available UDP-, TDP-, or GDP-sugars revealed no activity (data not shown). The enzyme assays were then carried out using UDP-GlcNAcA, the product of UGlcNAcDH, as an alternative substrate. Crude or purified UXNAcS readily converted UDP-GlcNAcA to another UDP-sugar with a retention time of 15.1 min (Fig. 4B, panels 2 and 3, asterisk), and such conversion requires exogenous NAD+ (Fig. 4B, panel 4).

FIGURE 4.

Expression and characterization of recombinant UXNAcS. A, SDS-PAGE of total soluble protein isolated from E. coli cells expressing UXNAcS (lane 2) or control empty vector (lane 3) and of nickel column-purified fractions (lane 4, UXNAcS; lane 5, control). B, high pressure liquid chromatogram of the UXNAcS enzyme reaction. Purified recombinant UXNAcS was incubated with UDP-GlcNAcA in the presence (panel 3) or absence (panel 4) of exogenous NAD+. As a control, the corresponding column-purified protein isolated from cells expressing control empty vector was incubated with UDP-GlcNAcA and NAD+ (panel 6). Activity of total protein isolated from cell expressing recombinant UXNAcS or vector control is shown in panels 2 and 5, respectively. The reaction products were separated on a Q15 column, and the UDP-sugar peak (marked by an asterisk in panels 2 and 3) was collected separately and analyzed by MALDI-MS and NMR.

MALDI-MS analysis of the new product indicates that it has a mass of 577.1, which would be expected for a UDP-pento-N-acetylamino sugar (supplemental Fig. S2, panel 2). To elucidate the product identity, the HPLC peak was collected and analyzed by NMR. Both one-dimensional proton (Fig. 5A) and two-dimensional HSQC (Fig. 5B) NMR spectroscopy provide unambiguous evidence that the enzymatic product is UDP-XylNAc.

FIGURE 5.

One- and two-dimensional 1H NMR analyses of the UXNAcS enzymatic product, UDP-XylNAc. A, one-dimensional 900-MHz NMR spectrum of the enzymatic product collected from the HPLC column (see Fig. 4B, panels 2 and 3, asterisk). The chemical shift of each proton residue on the spectrum is indicated; the positions of protons on the uracil (U) ring are indicated by H, the ribose (R) protons by H′, the XylNAc (X) protons by H″, and the C″-2 linked acetamido protons by NAc-H. The peak marked as HDO is the residual water signal. B, two-dimensional 900-MHz NMR spectrum of UDP-XylNAc. The selected region of a carbon-proton HSQC shows the ring protons and carbons of XylNAc and ribose, with the corresponding region of the proton spectrum above. ***, peaks corresponding to column impurities.

The chemical shift assignments for UDP-XylNAc are summarized in supplemental Table S1. The diagnostic J1″,2″ value of 3.3 Hz and J2″,3″, J3″,4″, J5b″,4″, and J5a″,5b″ values of 9.6, 10, 10.2, and 11.2 Hz, respectively, indicate an α-xylo configuration. The linkage of the anomeric XylNAc residue with the phosphate is given by the coupling constant values of 6.8 and 3.0 Hz for J1″,P and J2″,P, respectively, and is also supported by the distinct chemical shift of H″1 (5.454 ppm). In addition, the NAc-C=O resonance was assigned 2.064 ppm, and the specific H″2 chemical shift (3.962 ppm) is consistent for a C″-2-acetamido moiety of UDP-XylNac. Collectively, we thus concluded that UXNAcS encodes a newly identified specific UDP-GlcNAcA decarboxylase that forms UDP-XylNAc, hence the name UXNAcS.

Real-time NMR Analyses of UDP-GlcNAc Dehydrogenase and UDP-XylNAc Synthase Activities

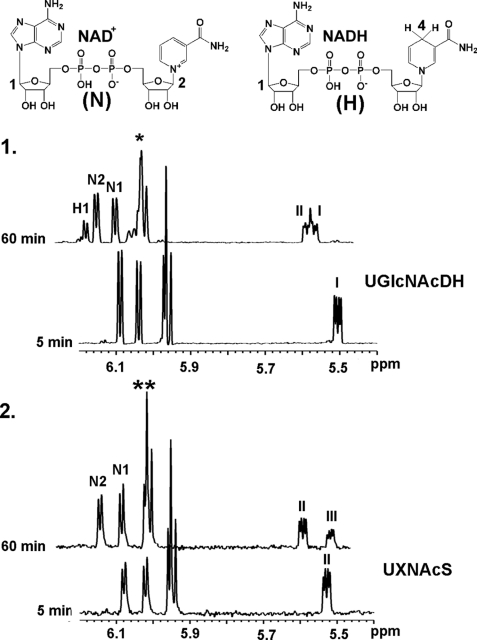

The real-time NMR assays were performed with each individual enzyme and its corresponding substrate as well as a combined assay that comprises both enzymes (the dehydrogenase and the decarboxylase). The latter assay was conducted to determine if any intermediates could be observed. The UGlcNAcDH activity is shown in Fig. 6, panel 1. As time progresses, the peak corresponding to the UDP-GlcNAc anomeric proton (peak I) is decreased, whereas peaks related with NADH (H1) and UDP-GlcNAcA (peak II) are increased, confirming the enzymatic conversion of UDP-GlcNAc and NAD+ into UDP-GlcNAcA and NADH.

FIGURE 6.

Monitoring individual UGlcNAcDH and UXNAcS assay by real-time one-dimensional NMR. The single-enzyme assay of UGlcNAcDH is shown in panel 1, and that of UXNAcS is shown in panel 2. All reactions were performed at 37 °C. The selected regions for the diagnostic peaks for NAD+, NADH, and the anomeric protons of the NDP-sugars are shown between 5.4 and 6.2 ppm at 5 min or 60 min after each reaction was initiated. The labeling for NAD+ and NADH protons refers to the corresponding compounds shown above. Peaks labeled as I, II, or III indicate the anomeric protons of UDP-GlcNAc, UDP-GlcNAcA, or UDP-XylNAc, respectively. Peaks marked by an asterisk (from 5.9 to 6.0 ppm) in panel 1 are the mixture of signals for Rib-H1′ and Ura-H5 protons of UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-GlcNAcA. Peaks marked by a double asterisk (from 5.9 to 6.0 ppm) in panel 2 are the mixture of signals for Rib-H1′ and Ura-H5 protons of UDP-GlcNAcA and UDP-XylNAc.

The UXNAcS assay is shown in Fig. 6, panel 2. As the enzymatic reaction progresses, the diagnostic anomeric proton of UDP-GlcNAcA (peak II) is decreased and concomitantly an increase of UDP-XylNAc (peak III) is observed. It should be noted that no variation was observed for the peaks belonging to NAD+ protons (N1 and N2) (Fig. 6, panel 2) in the UXNAcS assay, suggesting that the enzyme-bound NAD+ is not released as NADH during the C-4 oxidation (NAD+ → NADH)/reduction (NADH → NAD+) cycle.

The dual enzyme assay, including both Bacillus UGlcNAcDH and UXNAcS, is shown in supplemental Fig. S3. Over the reaction time, as the dehydrogenase converts UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-GlcNAcA, the peaks corresponding to the anomeric proton of UDP-GlcNAc (peak I in supplemental Fig. S3, panel 2) are decreased, and those of UDP-GlcNAcA increase (Peak II); simultaneously, an increase in peaks related to NADH proton (H1 in supplemental Fig. S3, panel 1) and the two diagnostic protons attached to C4 of the nicotinamide ring, H-4a and -4b (supplemental Fig. S3, panel 3) is observed. As the reaction progresses, the increase of UDP-XylNAc anomeric proton (peak III) is also observed (supplemental Fig. S3, panel 2), indicating the formation of UDP-XylNAc by UXNAcS. No other intermediate compounds were observed.

Characterization and Properties of UXNAcS

The optimal pH and temperature for the activity of Bacillus UDP-XylNAc synthase is around 8.2 and 37 °C (supplemental Fig. S4). The enzyme shows substantial activity at high pH as well, but no activity was observed below pH 4 (supplemental Fig. S4). The Bacillus UXNAcS was completely inhibited by NADH but not by its analog, NADPH (Table 1), suggesting the strict recognition of the enzyme for the C2-OH ribosyl group of the adenine moiety in NADH. UDP-xylose and UDP-GlcA had no adverse effects on UXNAcS activity. This might suggest that the UXNAcS recognition of the C″2-acetamido moiety of the UDP-XylNAc is critical. Other nucleotides, aside from UDP, or nucleotide-sugars (Table 1) had no significant effects on the decarboxylase activity. The enzyme is specific and did not react when NADP+ was substituted for NAD+ or when UDP-GlcNAcA was substituted with other UDP-uronates, such as UDP-GlcA and UDP-GalA (data not shown). Size exclusion chromatography (supplemental Fig. S5) analyses suggest that the decarboxylase is active as a dimer because it elutes from the Superdex-200 gel filtration column with a mass corresponding to 70,200 Da. Kinetics analyses of the UDP-XylNAc synthase activity are summarized in Table 2. The apparent Km value was 67 μm, the Vmax value (μm/s) was 0.2, and the kcat/Km value (s−1 mm−1) was 7. These kinetic values are comparable with other bacterial decarboxylase enzymes, such as RsU4kpxs (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

The effects of nucleotides and nucleotide sugars on UXNAcS activity

| Additives | Relative activity of UXNAcSa |

|---|---|

| % | |

| Water | 100 ± 1.4 |

| UDP-glucose | 99 ± 3.8 |

| UDP-galactose | 105 ± 2.4 |

| UDP-xylose | 101 ± 2.0 |

| UDP-arabinose | 95 ± 3.3 |

| UDP-GlcNAc | 103 ± 1.2 |

| UDP-GalNAc | 97 ± 0.9 |

| UDP-GlcA | 70 ± 2.0 |

| UDP | 48 ± 2.4 |

| UMP | 93 ± 2.1 |

| NADP | 97 ± 5.3 |

| NADPH | 92 ± 6.8 |

| NADH | 0 |

a Recombinant enzyme was incubated with 0.5 mm NAD+ in the absence or presence of different 0.5 mm nucleotides and nucleotide sugars for 15 min prior to the addition of 0.5 mm UDP-GlcNAcA. 100% activity corresponds to 15 nmol of UDP-XylNAc produced. The data presented are the average from three experiments.

TABLE 2.

Enzymatic kinetics of recombinant UXNAcS

| Kma | Vmax | kcat | kcat/Km | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm/s | s−1 | mm−1s−1 | |

| UXNAcS | 67 ± 6.0 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 7 ± 0.4 |

| RsU4kpxsb | 22 ± 1.2 | 0.07 ± 0.005 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 13 ± 0.3 |

a UXNAcS activity was measured with varied concentrations of UDP-GlcNAcA (0.08–1.0 mm) and 1 mm NAD+, after 8 min at standard conditions. The reciprocal initial velocity was plotted against the reciprocal UDP-GlcNAcA concentration according to Lineweaver and Burk to calculate the corresponding Km values. The data presented are the average Km values from three experiments.

b The kinetic data for the decarboxlyase activity of RsU4kpxs were taken from Ref. 10.

DISCUSSION

We have described the biosynthesis of a new UDP-amino sugar, UDP-XylNAc, and the cloning and characterization of a previously unknown decarboxylase activity. UXNAcS shares ∼30% amino acid sequence identity with known UDP-GlcA decarboxylases; despite that low similarity, they appeared to maintain a conserved fold and, most likely, similar catalytic mechanism throughout evolution. A putative structural model was created using human Uxs1 with bound NAD+ and UDP as a template (Protein Data Bank entry 2b69) by the aid of the PHYRE (25) structural prediction program. These two enzymes share a highly conserved structural fold (see supplemental Fig. S6), which consists of a central domain with structure resembling the Rossmann fold. In addition to the conserved structure, the catalytic motifs and the NAD+-binding domain, the predicted three-dimensional model of UXNAcS is almost indistinguishable from the human Uxs. However, the predicted UXNAcS model has some differences, specifically at the region around amino acid 266–282, when compared with the human Uxs1 (supplemental Fig. S6). We speculate that this region is probably involved in the interaction with the C″-2 acetamido moiety. Based on the predicted UXNAcS model, another region appears different near amino acids 47–53. Obviously, pointing out the exact UXNAcS amino acids that are involved in ligand binding (the nature of NAD+ association and the specificity for the acetamido group binding) and catalysis will require site-directed mutagenesis and a real crystal structure.

The genomes of B. cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98 and its closest pathogenic relatives, B. anthracis and the insecticidal B. thuringiensis, all contain the same operon for UDP-XylNAc synthesis. Interestingly, the non-pathogen B. subtilis does not carry this operon, and based on the current genome sequences, it is likely that no other organism carries this UXNAcS gene. But, we cannot exclude the possibility that an organism may have a UXNAcS homolog with a low sequence similarity to the Bacillus UXNAcS. Our work also illustrates that functional biochemical analysis is essential and that homology is an insufficient criterion from which to infer functional specificity.

In addition, several questions regarding the Bacillus UXNAcS can be raised. Is there any specific advantage for those Bacillus species that harbor UXNAcS? Did other microbes originally have UXNAcS and then lose it? Was the UXNAcS gene in these Bacillus species evolved from a rapidly evolving Uxs-like gene? From an evolutionary point of view, the UDP-sugar decarboxylase protein family is currently divided into three separate clades, the Uaxs, the ArnA and U4kpxs, and the Uxs, all proposed to be derived from the same ancestral Uxs/Uaxs-like enzyme (10). Phylogeny analyses as shown in supplemental Fig. S1B, places the Bacillus UXNAcS as a distinct clade from the Uxs. This suggests that the bacteria Uxs is unlikely to be the ancestral enzyme to the UXNAcS. How UXNAcS originated and what was led to the selective mutations resulting in the utilization of the UDP-GlcNAcA as substrate, however, is still ambiguous.

Nature produced diverse glycans decorated with different amino sugars, such as 2-deoxy-hexosamines and 6-deoxy-hexosamines, that are common in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria species. Peptidoglycan, for example, a critical bacterial cell wall polymer, is composed of alternating residues of β-1,4-linked N-acetylmuramic acid and GlcNAc (26, 27), and the aminoglycoside antibiotics produced by certain microbes contain different types of amino sugars as well (28). Amino sugar-modified glycans are also common in eukaryotes. GalNAc-residue, for example, is a predominant glycosyl residue in the core structure of O-linked glycans in humans and certain animals (29–32). The metabolism leading to the synthesis of such diverse glycans requires specific NDP-amino sugar precursors, and as such, malfunction in the activated sugar biosynthesis pathways might be lethal. Some UDP-amino sugar may also serve as intermediates for the synthesis of other nucleotide-amino sugars, like UDP-GlcNAcA for the synthesis of UDP-ManNAc(3Ac)A, a proposed sugar precursor for the synthesis of O-antigen in P. aeruginosa (33). However, the role for UDP-XylNAc, specifically in this food-poisoning Bacillus strain, remains elusive and is currently under investigation using a non-human pathogen strain as a model.

The XylNAc residue has not yet been observed in polysaccharides. The XylNac residue, however, was used as a chemical substitution for the GlcNAc residue in peptidoglycan for the study of the polysaccharide hydrolytic enzyme, lysozyme (34). Interestingly, the B. thuringiensis peptidoglycan cell wall is recalcitrant to hydrolysis by lysozyme (35). Whether this is in part due to XylNAc residues in the Bacillus wall polysaccharide remained to be determined. On the other hand, there are limited reports of xylosamines in glycosides. For example, some diamino xylosides have been found in certain antibiotics (36, 37), one of which was isolated from members of Nocardiopsis species (36). Whether the pathogenic Bacillus species also synthesize antimicrobial xylosamine-glycosides, however, is still unclear. Interestingly, analyses of the Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. dassonvillei DSM 43111 genome, with the Bacillus UXNAcS and UGlcNAcDH proteins point to an operon containing several genes, and among them are NdasDRAFT_3140 (ZP_04334040, we named “DH”) and NdasDRAFT_3141 (ZP_04334041, we named “DC”). The Nocardiopsis DH and DC share 27% amino acid sequence identity to the UGlcNAcDH and 38% identity to the UXNAcS described in this report, respectively. Despite the low sequence identities, it is possible that these Nocardiopsis enzymes are involved in the formation of xylosamine antibiotics, such as glycocinnamoylspermidines or macrolactam glycoside-like incednine. In addition, the organization of the N. dassonvillei operon is found also in genomes of several other members of the Nocardiopsis species. Within this Nocardiopsis operon and its surrounding gene clusters, there are several additional genes encoding potential glycosyltransferases, acyl-carrier protein, and other NDP-sugar biosynthetic enzymes. Whether these Nocardiopsis proteins are involved in the formation of these powerful antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria is currently under investigation. Taken together, the genes described in this report along with other surrounding Bacillus genes could be involved in production of xylosamine antimicrobial agents in this pathogenic bacterium.

In conclusion, this unique UXNAcS enzyme in pathogenic Bacillus species has not yet been found in any other organism and could be a potential drug target to eradicate the devastating anthrax and food poisoning diseases both in humans and livestock.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alexei Sorokin (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, France) for sharing the genomic DNA of B. cereus subsp. cytotoxis NVH 391-98.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant IOB-0453664 (to M. B.-P.). This work was also supported in part by BESC, the BioEnergy Science Center, which is supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research in the Department of Energy Office of Science. This research also benefited from activities at the SE Collaboratory for High-Field Biomolecular NMR, a research resource at the University of Georgia, funded by NIGMS, National Institutes of Health, Grant GM66340 and the Georgia Research Alliance.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the Gen-BankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) GU784842 and GU784843.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6 and Table S1.

X. Gu and M. Bar-Peled, unpublished observations.

- GlcA

- glucuronic acid

- GlcNAcA

- N-acetylglucosaminuronic acid

- XylNAc

- N-acetylxylosamine, α-d-2-acetamido-2-deoxyxylose

- HPLC

- high pressure liquid chromatography

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- Uxs

- UDP-xylose synthase

- Uaxs

- UDP-apiose/UDP-xylose synthase

- U4kpxs

- UDP-4-ketopentose/UDP-xylose synthase

- MALDI

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MS

- mass spectrometry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lapidus A., Goltsman E., Auger S., Galleron N., Ségurens B., Dossat C., Land M. L., Broussolle V., Brillard J., Guinebretiere M. H., Sanchis V., Nguen-The C., Lereclus D., Richardson P., Wincker P., Weissenbach J., Ehrlich S. D., Sorokin A. (2008) Chem. Biol. Interact. 171, 236–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stenfors Arnesen L. P., Fagerlund A., Granum P. E. (2008) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 579–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henriques A. O., Moran C. P., Jr. (2007) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 555–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox A., Stewart G. C., Waller L. N., Fox K. F., Harley W. M., Price R. L. (2003) J. Microbiol. Methods 54, 143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotiranta A., Lounatmaa K., Haapasalo M. (2000) Microbes Infect. 2, 189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hwang H. Y., Horvitz H. R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14218–14223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harper A. D., Bar-Peled M. (2002) Plant Physiol. 130, 2188–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bar-Peled M., Griffith C. L., Doering T. L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12003–12008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guyett P., Glushka J., Gu X., Bar-Peled M. (2009) Carbohydr. Res. 344, 1072–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu X., Glushka J., Yin Y., Xu Y., Denny T., Smith J., Jiang Y., Bar-Peled M. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9030–9040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breazeale S. D., Ribeiro A. A., Raetz C. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2886–2896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Götting C., Kuhn J., Zahn R., Brinkmann T., Kleesiek K. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 304, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhn J., Götting C., Schnölzer M., Kempf T., Brinkmann T., Kleesiek K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4940–4947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherniak R., Sundstrom J. B. (1994) Infect. Immun. 62, 1507–1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaishnav V. V., Bacon B. E., O'Neill M., Cherniak R. (1998) Carbohydr. Res. 306, 315–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klutts J. S., Doering T. L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14327–14334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohnen D. (2008) Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 11, 266–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peña M. J., Zhong R., Zhou G. K., Richardson E. A., O'Neill M. A., Darvill A. G., York W. S., Ye Z. H. (2007) Plant Cell 19, 549–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu X., Wages C. J., Davis K. E., Guyett P. J., Bar-Peled M. (2009) J. Biochem. 146, 527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allard S. T., Giraud M. F., Whitfield C., Graninger M., Messner P., Naismith J. H. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 307, 283–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerratana B., Cleland W. W., Frey P. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 9187–9195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao S. T., Rossmann M. G. (1973) J. Mol. Biol. 76, 241–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weirenga R. K., Terpstra P., Hol W. G. (1986) J. Mol. Biol. 187, 101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller W. L., Wenzel C. Q., Daniels C., Larocque S., Brisson J. R., Lam J. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37551–37558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley L. A., Sternberg M. J. (2009) Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaser L. (1973) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 42, 91–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vollmer W. (2008) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 287–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo F., Eguchi T. (2009) J. Antibiot. 62, 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsson J. M., Karlsson H., Sjövall H., Hansson G. C. (2009) Glycobiology 19, 756–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanover J. A. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 1865–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ten Hagen K. G., Fritz T. A., Tabak L. A. (2003) Glycobiology 13, 1R–16R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kubota T., Shiba T., Sugioka S., Furukawa S., Sawaki H., Kato R., Wakatsuki S., Narimatsu H. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 359, 708–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larkin A., Imperiali B. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 5446–5455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballardie F. W., Capon B., Cuthbert M. W., Dearie W. M. (1977) Bioorg. Chem. 6, 483–509 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Temeyer K. B. (1987) J. Gen. Microbiol. 133, 503–506 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin J. H., Kunstmann M. P., Barbatschi F., Hertz M., Ellestad G. A., Dann M., Redin G. S., Dornbush A. C., Kuck N. A. (1978) J. Antibiot. 31, 398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaishi M., Kudo F., Eguchi T. (2008) Tetrahedron 64, 6651–6656 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.