Abstract

Purpose:

Clinical differentiation of choroidal pigmented lesions is sometimes difficult. Choroidal melanoma is the most prevalent primary neoplasia among malignant ocular tumors, and metastasis often occurs before the primary tumor is diagnosed. Therefore, early detection is essential. We investigated the imaging properties of clinically diagnosed melanocytic choroidal tumors using a nonmydriatic ultra-wide-field scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) with two laser wavelengths to distinguish benign from malignant lesions. Repeated standardized ultrasound (US) evaluation provided reference standard.

Methods:

In a consecutive series of 49 patients with clinically diagnosed melanocytic choroidal tumors in one eye, 29 had established melanoma (defined by proven growth on repeated US follow-up) and 20 had nevi (defined by no malignancy according to clinical, US, and growth characteristics for at least 2 years). All patients underwent clinical examination, undilated Optomap® (Optos PLC, Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland, UK) imaging, standardized US examination, and standard retinal photography. Measurements of the tumor base using the Optomap software were compared with US B-scan measurements. Imaging characteristics from the SLO images were correlated with the structural findings in the two patient groups.

Results:

Measurements of tumor base correlated well between SLO and US with r = 0.61 (T-direction) and r = 0.51 (L-direction). On SLO imaging, typical malignant lesions appeared dark on the red laser channel and bright on the green laser channel. Based on those simple binary characteristics, a sensitivity of 76% at a specificity of 70% was obtained for a correct classification of lesions. When analogous to clinical examination lesion size, margin touching the optic disc, and existence of subretinal fluid were additionally considered, 90% sensitivity at 82% specificity was obtained.

Conclusions:

In this first, limited series, nonmydriatic SLO imaging with two laser wavelengths permitted to differentiate malignant ocular tumors from nonmalignant lesions with high diagnostic accuracy. Additional parameters may further enhance diagnostic properties, but larger patient series are required to validate our findings and prove the diagnostic properties.

Keywords: choroidal melanoma, nevus, imaging, ultra-wide-field scanning laser ophthalmoscopy

Introduction

Pigmented choroidal lesions are a common finding on the ocular fundus. Most of these lesions can be differentiated by their clinical appearance together with their angiographic and ultrasonographic (US) characteristics. However, distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions is sometimes difficult. Most choroidal lesions are benign, and the overall incidence of malignancies in the form of choroidal melanoma is low (approximately six new cases per million per year in the United States). Nonetheless, choroidal melanoma is the most frequent primary malignant intraocular tumor and the second most frequent malignant melanoma in the body.1 Benign choroidal nevi are common and can be found in approximately 6% of the US population.2–5 Choroidal melanoma can arise de novo as well as from pre-existing choroidal nevi.6–8 Therefore, choroidal nevi should be monitored regularly. In addition, early detection of malignant lesions is extremely important because progressive tumors have a very poor prognosis.9–12

On the other hand, especially in smaller lesions, differentiating choroidal nevi from small choroidal melanoma is difficult and concern about malignant transformation is always present.12–14 Consequently, several studies have attempted to distinguish small choroidal melanomas from choroidal nevi and to identify risk factors for growth of small choroidal tumors.1,12,15,16

Biomicroscopy of the fundus and photographic color fundus imaging are the most commonly used techniques for diagnosing and documenting choroidal lesions. However, both techniques are sometimes insufficient to differentiate lesions accurately. Even with combined clinical, angiographic, and US findings, diagnosis sometimes remains uncertain.1,11,12,14–16

Recently, a novel ultra-wide-field scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) with two laser wavelengths, the Optomap® Panoramic 200MA (Optos PLC, Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland, UK), was developed. The system allows nonmydriatic imaging and by differentiating the two laser scans, provides additional image information. Optomap Panoramic 200MA images encompass not only the posterior pole but also extend over the equator.17

This study evaluates measurements of the tumor base using the Optomap Vantage V2 software vs the reference standard, standardized US evaluation, which is a well established, highly sensitive, and specific method to measure and differentiate intraocular tumors.18,19 In addition, the diagnostic properties of Panoramic 200MA images to separate benign from malignant lesions of the ocular fundus were investigated. For this, a number of imaging characteristics from the two-wavelength SLO images were investigated for their ability to differentiate a nevus and melanoma patient group.

Methods

Patients

In a consecutive series of 49 patients (20 men and 29 women) comprising 49 eyes (26 OD and 23 OS) with clinically diagnosed melanocytic choroidal tumors, 29 had established melanoma (defined by proven growth on repeated US follow-up). Of these patients, 20 had received radiation therapy (9 in total showed radiation signs funduscopically) and 9 were untreated at the time of examination. The remaining 20 patients had nevi as defined by no malignancy based on clinical and US examinations and no growth for at least 2 years. The median age of patient was 64 years (range, 39–85 years). After informed consent was obtained, all patients underwent clinical examination, undilated Optomap imaging, standardized US examination, and standard retinal photography. The study fully conformed to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki, and Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Standardized US examination

The same equipment was used for all patients for A-scan and B-scan examination (Ultrasound Cinescan-S, Memory Card Version S 2.07; QuantelMedical, Clermont-Ferrand, France). We followed the specific criteria described by Ossoinig et al20 to evaluate an intraocular tumor with standardized US. In brief, the eye was open during examination and each examination consisted of a preliminary topographic B-scan evaluation. B-scan was also used to evaluate the shape of the lesion and to measure both the maximum transverse, circumferential basal tumor diameter (T-direction) and longitudinal, radial basal tumor diameter (L-direction) of the tumor base with calipers.20 A relatively low gain setting was used to obtain the best measurement, and we identified the inner sclera as the first distinct line of the tumor base that was continuous with the surrounding fundus. Gain settings for B-scan evaluation were not specified. Tumor height measurements were then obtained only with the standardized A-scan, not the B-scan.20 The standardized A-scan instrument was first set at tissue sensitivity, according to the principles described by Ossoinig et al20 with the probe placed at the opposite side of the tumor. Careful attention was paid to the perpendicular orientation of the sound beam with respect to the point of maximal tumor elevation and the inner sclera. Once the tumor surface spike and the scleral spike were displayed with their maximum height, we lowered the gain while continuously monitoring the screen until the peaks were distinct and clear. We obtained measurements by placing calipers on the peak of the tumor surface spike and the inner scleral spike and then took at least three high-quality images. The examiner selected the photograph representing the most accurate measurement and recorded the tumor height. Other documented parameters were shape, internal reflectivity (low, medium, and high), internal structure (homogeneous-regular, heterogeneous-regular, and irregular), vascularity (positive and negative), retinal detachment (positive and negative), and location (posterior, equator, and anterior).

Optomap imaging

Optomap imaging was performed without pupil dilation, prior to and independent of clinical and US examinations. Optomap imaging consisted of taking several images and saving the best image per eye for grading. The instrument takes one image in approximately 0.25 seconds thus avoiding motion artifacts. Total scanning time was about 3–5 minutes, which included patient positioning, and was performed by an experienced technician or one of the authors. Basic operation of the Optomap Panoramic 200MA is an SLO with two scanning laser wavelengths: one green (532 nm) and one red (633 nm). The two images can be viewed separately or superimposed to yield semirealistic color imaging. The instrument requires a small optical path of only 2 mm and its mirror design allows obtaining wide-field images of approximately 180–200° without pupil dilatation. The optical resolution with the specific instrument used in our study was 3,900–3,072 pixels, resulting in approximately 17–20 pixels per degree. Due to the SLO, principal images of high contrast and sharpness were obtained, which showed less susceptibility to media opacities than conventional photography.21

Image analysis and statistics

The retinal images were loaded from the server to a viewing station (equipped with a conventional 17-inch noncalibrated cathode ray color monitor) via network and assessed with the Optomap Vantage V2 software. This software allows basic image manipulations such as changing contrast and brightness and zooming, as well as measuring specific lesions using calipers. It also offers views of both composite color and single-wavelength images. We compared the images obtained at the different wavelengths to better differentiate the level at which the lesions were located; unlike the longer red laser wavelength, the green laser cannot penetrate significantly below the retinal pigment epithelium. Two experienced retina specialists independently graded the images. They had not previously participated in patient examinations and were masked to all additional information such as visual acuity or clinical symptoms. They could, however, decline assigning a grade due to insufficient image quality, which was defined as not covering at least the central 60° and both the macula and the optic disc.

Measurements included are the following:

– Location of the lesion: margin touching the optic disc according to the Shields et al12 definition (yes/no);

– Existence of subretinal fluid at or surrounding the pigmented lesion (yes/no);

– Lesion appearance in red channel (dark/bright/mixed);

– Lesion appearance in green channel (dark/bright/mixed);

– Lesion size (transversal and longitudinal diameter in pixels). The maximum diameter was measured on Optomap. Measurements were standardized according to individual optic disc size defined as the mean horizontal and vertical disc diameters. For this known average, planimetry mean diameters of 1.92 mm vertically and 1.76 mm horizontally were used according to Jonas et al.22

Irregular lesion brightness or drusen was described and in case of major irregularity, the lesion appearance was graded as “mixed”. The first step in analysis of the obtained data was to prepare a scatter plot of measurements of the tumor basal diameters determined from Optomap images and those estimated from B-scan US images and perform correlation analysis on the plotted points of the tumor base on Optomap to US B-scan measurements. In a second step, we compared the Optomap imaging characteristics from the two-wavelength SLO images with the clinical definition and findings in the nevi and melanoma groups. To minimize bias from including pretreated melanoma patients in the study, we performed reanalysis excluding those 9 patients with signs of radiation. We collected and analyzed all data using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Correlation of Optomap imaging with US measurements

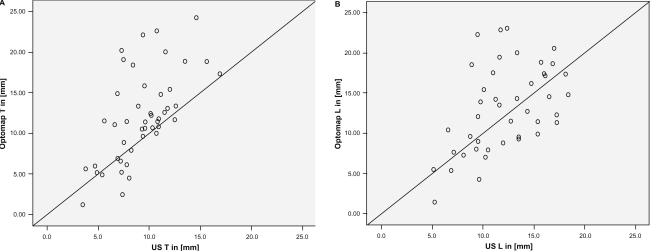

Measurements of tumor base correlated statistically significant between SLO and US with r = 0.61 (T-direction, Spearman) and r = 0.51 (L-direction; Figure 1A and B). Optomap measurements were statistically significantly higher (P < 0.001) than US for measurements in the T-direction, yielding a mean difference of 2.8 mm. However, US and SLO measurements did not differ significantly in the L-direction (Wilcoxon).

Figure 1.

Base diameters of lesions measured in US and Optomap. A) T-direction and B) L-direction.

Imaging characteristics nevi vs melanoma with Optomap

The Optomap imaging details obtained in the two groups (nevi vs melanoma) are shown in Table 1 for the image characteristics investigated. With SLO imaging, malignant lesions typically appeared dark on the red laser channel and bright on the green laser channel. Figures 2–4 give representative examples for Optomap imaging of malignant vs benign pigmented fundus lesion.

Table 1.

Imaging characteristics nevi vs melanoma

| Characteristics on optomap | Nevi group, n = 20 | Melanoma group, n = 29 | Statistically significant difference nevi–melanoma, ANOVA, post hoc testing | Melanoma subgroup without any signs of radiation therapy, n = 20 out of 29 | Clinical melanoma characteristics as defined by Shields and Shields11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location touching optic disc | 3 (15%) | 8 (28%) | Ns | 5 (25%) | M = margin touch optic disc |

| Subretinal fluid | 7 (35%) | 14 (48%) | Ns | 13 (65%) | F = subretinal fluid |

| Red channel imaging | 12 dark | 23 dark | Ns | 16 dark | O = orange pigment |

| 7 bright | 4 bright | 2 bright | |||

| 1 mixeda | 2 mixeda | 2 mixeda | |||

| Green channel imaging | 2 dark | 6 dark | P = 0.011 | 3 dark | |

| 11 bright | 22 bright | 16 bright | |||

| 7 mixeda | 1 mixeda | 1 mixeda | |||

| Size T, in mm (mean ± SD) | 8.18 ± 3.77 | 15.59 ± 4.69 | P < 0.001 | 13.79 ± 4.26 | T = thickness >2 mm; >1mm (for metastasis) |

| Size L, in mm (mean ± SD) | 7.88 ± 3.75 | 13.67 ± 4.00 | P < 0.001 | 12.62 ± 4.49 | |

| Clinical parameter (not included in this imaging study) | S = symptoms | ||||

| Only available at follow-up examination | G = growth (for metastasis) | ||||

Note:

Mixed, irregular pattern not allowing a binary classification.

Abbreviations: ns, not significant; SD, standard deviation; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

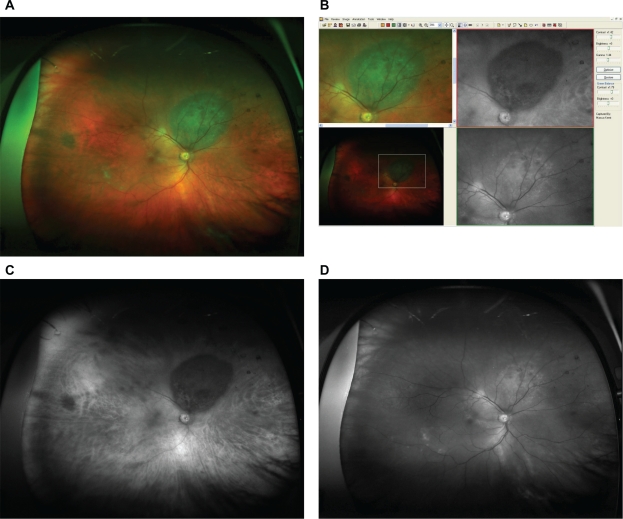

Figure 2.

A) Optomap composite image showing the typical appearance of an untreated choroidal melanoma (red and green channel superimposed). B) Detail of the fundus image from Figure 2A, as viewed with the specific Optomap viewing software (composite image on the left, red and green separation on the right). The lesion appears dark in the red channel and bright in green channel. C) Red separation image (untreated melanoma). D) Green separation image (untreated melanoma).

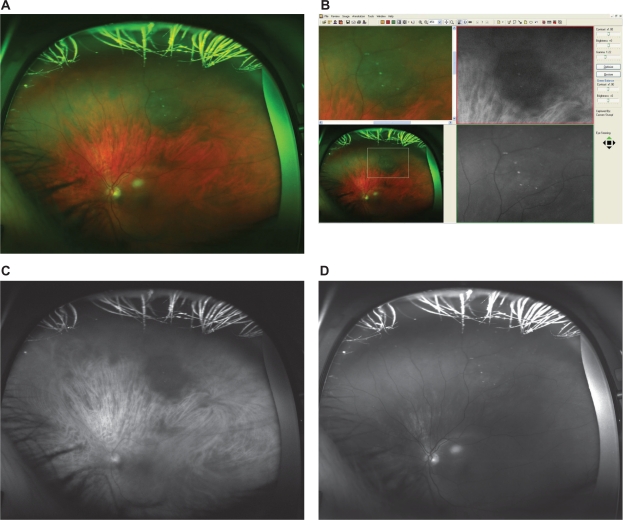

Figure 4.

A) Optomap composite image showing the typical appearance of a choroidal melanoma after radiation therapy (red and green channel superimposed). B) Detail of the according fundus image from Figure 4A, as viewed with the specific Optomap viewing software (composite image on the left, red and green separation on the right). The lesion appears bright in the red channel and bright in green channel. C) Red separation image (treated melanoma). D) Green separation image (treated melanoma).

Group differentiation by Optomap image features

Based only on the simple, mostly binary characteristics of a lesion’s appearance with Optomap imaging, a binary logistic regression analysis was calculated to obtain a simple overall predictor for malignancy. This relied only on the brightness imaging features available from the Optomap images and yielded a sensitivity of 76% at a specificity of 70%. The green channel (odd ratio [OR], 0.23; P = 0.02) was more predictive than the red channel (OR, 0.65; not significant). Overall fit was low with a Nagelkerke R2 of 0.20.

If in addition the T-diameter and L-diameter with Optomap imaging, contact with the optic disc and existence of subretinal fluid were considered, a 90% sensitivity at a 82% specificity was obtained. The overall Nagelkerke R2 reached 0.63 with the strongest predictors being subretinal fluid (OR, 2.1) and lesion size (T-direction OR, 1.5; L-direction OR, 1.1). The green and red channel images on Optomap retained a similarly high importance (green channel OR, 0.5; red channel OR, 0.45).

Discussion

Choroidal melanomas account for the largest proportion of malignant melanomas after those involving skin and are the most frequent primary intraocular tumor.1 Due to their malignancy and the very poor prognosis associated with progressing tumors, early detection is extremely important.8–12 Diagnostic criteria for differentiating malignant from nonmalignant lesions are controversial and often seem arbitrary.4,23,24 However, size (mainly a lesion’s thickness but also the basal diameter) is one of the most important clinical features. If a lesion enlarges convincingly during follow-up, most ophthalmologists classify the tumor as at least probable choroidal melanoma.25 Nevertheless, clinical classification of pigmented choroidal lesions is often a great challenge for ophthalmologists.13 One reason for that may be a substantial overlap between choroidal nevi and melanoma, particularly for tumors between 1.5 and 3 mm of thickness having a basal diameter between 5 and 9 mm.25 Standardized A-scan US has become a valuable aid to establish the diagnosis of choroidal melanoma in such cases.20 However, this technique is not generally available; further, it is time consuming and requires an experienced operator. Therefore, especially for screening purposes, alternative, easy-to-handle diagnostic tools would be preferred.

The SLO Optomap P200MA is a nonmydriatic ultra-wide-field fundus imaging system that uses two laser wavelengths and is able to image up to 200° of the retina with 1 scan. It, therefore, allows suspicious lesions to be easily detected and has substantial screening abilities for several retinal diseases. In addition, separating the two laser scans provides further information because red laser better penetrates the deeper layers of the retina and the choroid, and green, red-free laser provides better images of the superficial layers of the retina and retinal vessels.26 Therefore, we investigated the diagnostic properties of nonmydriatic SLO imaging with two laser wavelengths with the Optomap Panoramic 200MA imaging device as a potential screening tool to differentiate clinically diagnosed melanocytic choroidal tumors.

This first, limited series yielded data that allowed differentiating malignant ocular tumors from nonmalignant lesions with high diagnostic accuracy. It must be kept in mind, though, that for the diagnostic features developed in our current patient group sensitivity and specificity are “theoretical”: those need to be proven and recalculated in an independent patient group. By separating red and green laser scans alone, we could evaluate very simple image properties, which provided a diagnostic sensitivity of 76% and a specificity of 70% without assessment of any other clinical parameters. Aiming to enhance diagnostic accuracy, Shields and Shields11 analyzed 1,287 patients presenting different choroidal lesions including both choroidal nevi and choroidal melanoma. As a result of their investigation, they identified five predictive clinical features of small choroidal melanoma growth to help clinicians better differentiate suspect lesions: tumor thickness >2 mm, presence of subretinal fluid, clinical symptoms, orange pigment overlying the surface of the tumor, and tumor margins touching or within 3 mm of the optic disc.12 These combined clinical parameters in combination allowed distinguishing malignant from clinically as nonmalignant diagnosed melanocytic choroidal tumors with high accuracy.11

Therefore, another aim of our study was to prove whether combining some of these criteria from Shields and Shields11 with the specific imaging characteristics from Optomap Panoramic 200MA images could improve diagnostic precision. We found that measurement of the tumor base, combined with an evaluation of subretinal fluid, assessment of the lesion locations on the ocular fundus, and the specific imaging criteria from Optomap led to a significant improvement of diagnostic accuracy allowing differentiation of malignant from nonmalignant ocular tumors in 90% of cases. This appears to exceed the diagnostic accuracy of photographic fundus imaging, although validation in an independent series is required. Indeed, standardized A-scan US conducted by an experienced operator might allow higher accuracy; however, with less experience of the investigator, diagnostic accuracy drops dramatically. Further, the technique itself might be less tolerated by patients than a simple imaging procedure and it is not widely available. In contrast, the Optomap imaging system is noninvasive and easy to handle. It also permits telescreening because data files from Optomap can be easily transferred online and can be examined anywhere in the world.

In summary, we showed that nonmydriatic SLO imaging with two laser wavelengths allowed differentiating malignant ocular tumors from nonmalignant lesions with relatively high accuracy. Lesion size measurements correlated reasonably well with US measurements. Additional parameters to describe and differentiate lesions may further increase diagnostic properties, and larger patient series are required to validate our findings.

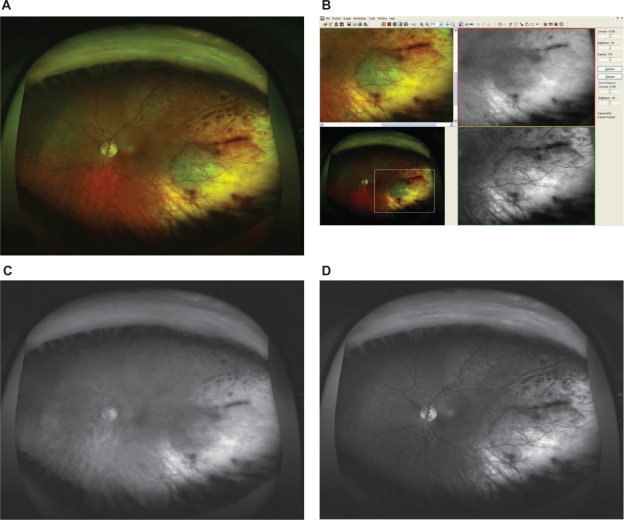

Figure 3.

A) Optomap composite image showing the typical appearance of a choroidal nevus (red and green channel superimposed). Due to the nonconfocal SLO imaging, some bright spots anterior to the lesion are imaged and some lashes in the upper part of the image also appear in focus. B) Detail of the according fundus image from Figure 3A, as viewed with the specific Optomap viewing software (composite image on the left, red and green separation on the right). The lesion appears dark in the red channel and dark in green channel. Due to the nonconfocal SLO imaging, some bright spots anterior to the lesion. C) Red separation image (nevus). D) Green separation image (nevus).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stefanie Guthmann and Rita Hauser for excellent technical assistance. Presented in part at the 9th Euretina meeting 2009 in Nice, France and at the International society for imaging in the eye (ISIE) meeting 2010 in Fort Lauderdale, USA.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors do not have any commercial or financial interest in any of the materials and methods used in this study.

References

- 1.Margo CE. The Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study: an overview. Cancer Control. 2004;11(5):304–309. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert DM, Robinson NL, Fulton AB, et al. Epidemikological investigation of increased incidence of choroidal melanoma in a single population of chemical workers. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1980;20(2):71–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balch CM, Murad TM, Soong SJ, Ingalls AL, Richards PC, Maddox WA. Tumor thickness as a guide to surgical management of clinical stage I melanoma patients. Cancer. 1979;43(3):883–888. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197903)43:3<883::aid-cncr2820430316>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganley JP, Comstock GW. Benign nevi and malignant melanomas of the choroid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;76(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Sains RS. Ocular findings in patients with dysplastic nevus syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(5):661–665. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnesen K, Nornes M. Malignant melanoma of the choroid as related to coexistent benign nevus. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1975;53(2):139–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1975.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahel JA, Pesavento R, Frederick AR, Jr, Albert DM. Melanoma arising de novo over a 16-month period. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(3):381–385. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130407031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanoff M, Zimmerman LE. Histogenesis of malignant melanomas of the uvea. II. Relationship of uveal nevi to malignant melanomas. Cancer. 1967;20(4):493–507. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1967)20:4<493::aid-cncr2820200406>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLean IW, Saraiva VS, Burnier MN., Jr Pathological and prognostic features of uveal melanomas. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39(4):343–350. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eskelin S, Pyrhonen S, Summanen P, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Kivela T. Tumor doubling times in metastatic malignant melanoma of the uvea: tumor progression before and after treatment. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(8):1443–1449. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shields CL, Shields JA. Clinical features of small choroidal melanoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13(3):135–141. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shields CL, Shields JA, Kiratli H, De Potter P, Cater JR. Risk factors for growth and metastasis of small choroidal melanocytic lesions. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1995;93:259–275. 275–279. discussion. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gass JD. Problems in the differential diagnosis of choroidal nevi and malignant melanomas. The XXXIII Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83(3):299–323. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields CL, Demirci H, Materin MA, Marr BP, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Clinical factors in the identification of small choroidal melanoma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2004;39(4):351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(04)80005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shields CL, Cater J, Shields JA, Singh AD, Santos MC, Carvalho C. Combination of clinical factors predictive of growth of small choroidal melanocytic tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(3):360–364. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler P, Char DH, Zarbin M, Kroll S. Natural history of indeterminate pigmented choroidal tumors. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(4):710–716. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31274-7. discussion 717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernt M, Ulbig MW. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Wide-field scanning laser ophthalmoscope imaging and angiography of central retinal vein occlusion. Circulation. 2010;121(12):1459–1460. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d99c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodes BL, Choromokos E. Standardized a-scan echographic diagnosis of choroidal malignant melanomas. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(4):593–597. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450040059006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ossoinig KC. Standardized echography: basic principles, clinical applications, and results. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1979;19(4):127–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ossoinig KC, Bigar F, Kaefring SL. Malignant melanoma of the choroid and ciliary body. A differential diagnosis in clinical echography. Bibl Ophthalmol. 1975;(83):141–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkpatrick JN, Manivannan A, Gupta AK, Hipwell J, Forrester JV, Sharp PF. Fundus imaging in patients with cataract: role for a variable wavelength scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(10):892–899. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.10.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonas JB, Gusek GC, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, Naumann GO. Correlations of the neuroretinal rim area with ocular and general parameters in normal eyes. Ophthalmic Res. 1988;20(5):298–303. doi: 10.1159/000266730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamler E, Maumenee AE. A clinical study of choroidal nevi. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1959;62(2):196–202. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1959.04220020022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naumann G, Yanoff M, Zimmerman LE. Histogenesis of malignant melanomas of the uvea. I. Histopathologic characteristics of nevi of the choroid and ciliary body. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;76(6):784–796. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1966.03850010786004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augsburger JJ, Correa ZM, Trichopoulos N, Shaikh A. Size overlap between benign melanocytic choroidal nevi and choroidal malignant melanomas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(7):2823–2828. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saari JM, Kivela T, Summanen P, Nummelin K, Saari KM. Digital imaging in differential diagnosis of small choroidal melanoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(12):1581–1590. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]