Abstract

Developmental timing in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is controlled by heterochronic genes, mutations in which cause changes in the relative timing of developmental events. One of the heterochronic genes, let-7, encodes a microRNA that is highly evolutionarily conserved, suggesting that similar genetic pathways control developmental timing across phyla. Here we report that the nuclear receptor nhr-25, which belongs to the evolutionarily conserved fushi tarazu-factor 1/nuclear receptor NR5A subfamily, interacts with heterochronic genes that regulate the larva-to-adult transition in C. elegans. We identified nhr-25 as a regulator of apl-1, a homolog of the Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein-like gene that is downstream of let-7 family microRNAs. NHR-25 controls not only apl-1 expression but also regulates developmental progression in the larva-to-adult transition. NHR-25 negatively regulates the expression of the adult-specific collagen gene col-19 in lateral epidermal seam cells. In contrast, NHR-25 positively regulates the larva-to-adult transition for other timed events in seam cells, such as cell fusion, cell division and alae formation. The genetic relationships between nhr-25 and other heterochronic genes are strikingly varied among several adult developmental events. We propose that nhr-25 has multiple roles in both promoting and inhibiting the C. elegans heterochronic gene pathway controlling adult differentiation programs.

Keywords: apl-1, Caenorhabditis elegans, heterochronic gene, developmental timing, let-7, nuclear receptor, nhr-25

Introduction

The temporal coordination of cell proliferation and differentiation during development is essential for the correct morphogenesis of multicellular organisms (Banerjee and Slack, 2002). The development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans serves as an excellent model to study how the temporal fates of cells are specified (Ambros, 2000). C. elegans development progresses through six stages: the embryonic stage, four larval stages (L1, L2, L3 and L4) that each end with a molt and the adult stage. At each stage, the timing of development is regulated such that specific cell types are produced during a particular developmental period (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977).

Genetic analyses have revealed a number of genes, the so-called heterochronic genes, which control the temporal regulation of postembryonic development in C. elegans (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Moss, 2007; Rougvie, 2005). Mutations in these heterochronic genes cause cells to adopt fates normally expressed at earlier or later stages of development in C. elegans. Progression through the first and second larval stages, L1 and L2, is controlled by the microRNA (miRNA) lin-4, which down-regulates the activity of transcription factor LIN-14 (Ambros, 2000). Later in larval development, members of the let-7 miRNA family control the L2-to-L3 and L4-to-adult transitions (Abbott et al., 2005; Esquela-Kerscher et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Reinhart et al., 2000) through the down-regulation of other heterochronic genes such as hbl-1 (Abrahante et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2003), lin-41 (Slack et al., 2000) and daf-12 (Grosshans et al., 2005). Recently, negative feedback networks between the let-7 family of miRNAs and their targets have been revealed, as daf-12 and hbl-1 regulate let-7 expression (Bethke et al., 2009; Hammell et al., 2009; Roush and Slack, 2009). The larva-to-adult (L/A) transition is controlled by the repression of hbl-1 and lin-41 through let-7, which in turn allows for the activation of lin-29. lin-29 encodes a transcription factor that ceases the larval developmental program and simultaneously induces adult cell differentiation (Rougvie and Ambros, 1995). Many of these heterochronic genes identified from C. elegans are evolutionarily conserved in genomes of diverse animal species (Moss, 2007). Some of the orthologs are conserved in terms of the regulation of developmental timing, as exemplified by the recent finding that a human ortholog of the C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-28 is genetically linked with the timing of human puberty (Ong et al., 2009). Among the conserved heterochronic genes, the let-7 miRNA family is an essential genetic component for developmental timing of various animal species, as its sequence and temporal expression pattern as well as several let-7 target genes are highly conserved during animal evolution (Johnson et al., 2005; Pasquinelli et al., 2000).

Although a number of key heterochronic genes downstream of let-7, including transcription factors and signal transduction molecules, have been identified (Grosshans et al., 2005; Lall et al., 2006), the molecular mechanisms underlying the developmental timing for adult differentiation programs are less well studied. For example, although lin-29 acts downstream of let-7 and its targets (Bettinger et al., 1996; Rougvie, 2005), little is known about mechanisms of lin-29 activation that promote adult differentiation. Therefore, uncharacterized genes could be acting in the heterochronic gene pathway to specify the appropriate execution of the adult differentiation program.

Here, we report a novel mechanism for regulation of developmental timing by the nuclear receptor (NR) gene nhr-25 in C. elegans. nhr-25 belongs to the evolutionarily conserved nuclear receptor NR5A subfamily, including insect fushi tarazu-factor 1 (FTZ-F1), mammalian steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1) and liver receptor homolog 1 (LRH-1) (Asahina et al., 2000; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000). Previous studies have shown that nhr-25 is necessary for a variety of developmental events, such as embryogenesis, hypodermal differentiation, exoskeleton production, vulval formation, and gonadal morphogenesis (Asahina et al., 2000; Asahina et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2004; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000; Hajduskova et al., 2009; Silhankova et al., 2005). nhr-25 is also a downstream target of let-7 and other heterochronic genes involved in the cessation of molting (Hayes et al., 2006). We demonstrate that nhr-25 plays a crucial role in regulating the L/A transition in C. elegans. Strikingly, the phenotypes of loss of nhr-25 function animals are not easily classified into either the “precocious” or “retarded” class of heterochronic genes. We propose that nhr-25 plays critical roles in the heterochronic gene pathway with the unique ability to both promote and inhibit certain adult differentiation programs in C. elegans and that these dual roles are dictated by its ability to genetically interact with multiple heterochronic genes.

Materials and methods

Nematode strains and culture

C. elegans strains were grown at 20 °C under standard conditions. Bristol N2 was used as the wild type. The mutant strains used were as follows:

-

-

hbl-1(ve18), a hypomorphic allele that deletes 5 base pairs nucleotides at a boundary of the second exon and the second intron of hbl-1 (Abrahante et al., 2003).

-

-

hbl-1(mg285), a hypomorphic allele that deletes 301 base pairs in the 5´ region of hbl-1, causing a frameshift predicted to truncate HBL-1 protein in the third exon (Lin et al., 2003).

-

-

let-7(n2853), a temperature-sensitive, point-mutated allele that exhibits a strong retarded phenotype (Reinhart et al., 2000).

-

-

lin-29(n546), a point mutation introducing a premature opal stop codon that eliminates the C-terminal 1/3 of the protein (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Rougvie and Ambros, 1995).

-

-

lin-41(ma104), a hypomorphic allele that has a transposon insertion in the twelfth exon (Slack et al., 2000).

-

-

lin-42(n1089), which contains a large deletion that removes part of exon 2 and exons 3–5, disrupting wild-type activity of three out of four lin-42 isoforms (Tennessen et al., 2006).

-

-

nhr-25(ku217), a hypomorphic allele that has a missense mutation causing L32F substitution in the DNA binding domain of NHR-25 (Chen et al., 2004).

To visualize the nuclei of seam cells, we utilized an integrated construct wIs51[scm::gfp]. To visualize both nuclei and junctions of seam cells, another integrated strain wIs79[ajm-1::gfp;scm::gfp] was used. maIs105[col-19::gfp] (Abbott et al., 2005) was kindly provided by C. Hammell and V. Ambros. Other transgenic strains used were nwrIs001[apl-1::gfp::unc-54] (Niwa et al., 2008), ctIs37[hbl-1::gfp::unc-54] (Lin et al., 2003), jmEx33[nhr-25::gfp::unc-54] (Silhankova et al., 2005) and TP12:kaIs12[col-19::gfp] (Thein et al., 2003).

RNAi experiments

Gene knockdown was achieved through RNAi by feeding as described (Timmons and Fire, 1998). A subset of Dr. Julie Ahringer’s RNAi library (Fraser et al., 2000) that includes clones for 387 predicted C. elegans transcription factors (Table S1) was purchased from Geneservice. Synchronized populations of L1 larvae were fed bacteria expressing dsRNA corresponding to the target genes. In mock RNAi experiments, bacteria carrying an empty vector pPD129.36 (Kamath et al., 2003) were used. The following PCR products used for RNAi experiments in this study were previously described (Kamath et al., 2003): sjj_F11A1.3 for daf-12, sjj_Y17G7A.2 for lin-29, sjj_C01H6.5 for nhr-23 and sjj_F11C1.6 for nhr-25. We confirmed that approximately 35 % of nhr-23(RNAi) animals (n=73) exhibited a defect in larval cuticle shedding at the L4 molt as previously reported (Kostrouchova et al., 1998). We also observed that daf-12(RNAi) significantly suppressed the bursting phenotype of let-7(n2853) (90 %; n=126), as previously described (Grosshans et al., 2005).

Observation of worms

Except the lin-42(n1089) worms, L4 animals were staged by the relative positions of their gonadal distal tip cells to the vulva: early, mid and late L4 animals were defined as animals showing 0-1/4, 1/4-1/2 and >1/2 gonadal turns, respectively, as previously described (Niwa et al., 2008). lin-42(n1089) L4 worms were staged by degrees of vulval invagination, because lin-42(n1089) exhibits precocious turning of gonadal tips as previously described (Tennessen et al., 2006). To observe GFP signals in seam cells of the apl-1::gfp transgenic lines, we observed all seam cells except the few cells surrounding the head and pharyngeal regions; the non-seam expression of apl-1::gfp in these regions is strong (Niwa et al., 2008) and interferes with evaluation of the GFP expression in seam cells. Therefore, “GFP in all seam cells”, as described in Fig. 1, means the apl-1::gfp animals showing GFP expression in all seam cells except the cells in the head region. A scanning election microscopic observation was performed as previously described (Silhankova et al., 2005) except worms were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS buffer and images were captured with JEOL JSM-7401F.

Fig. 1. nhr-25 is required for apl-1 expression in seam cells.

All worms shown in this figure were carrying an integrated array of apl-1::gfp::unc-54 constructs fused with the full 7.0 kb apl-1 promoter sequence. The GFP signals in seam cells are marked by arrowheads in A, C, E, and G. In DIC images, arrows and arrowheads point to gonadal distal tip cells and vulva, respectively. (A–C) Late L4 larvae carrying integrated apl-1::gfp::unc-54 constructs on RNAi plates of control (mock, A), nhr-25 (B) and nhr-23 (C). Images A–C were taken for the same exposure time and processed identically. (D) Temporal expression profiles of the apl-1::gfp::unc-54 strains with control (mock) RNAi, nhr-25 RNAi, nhr-23 RNAi, daf-12 RNAi, and nhr-25(ku217) mutation. (E–G) Precocious (early L4) apl-1::gfp expression in seam cells in hbl-1(ve18) mutant with RNAi for control (mock, E), nhr-25 (F), and nhr-23 (G). Images E–G were taken for the same exposure time and processed identically. (H) Percentage of animals showing apl-1::gfp::unc-54 expression in the wild type, hbl-1 and lin-42 backgrounds with mock RNAi, nhr-25 RNAi and nhr-23 RNAi in the early L4 stage. Open bars indicate that no GFP signal in seam cells was observed, shaded bars indicate that GFP signals were observed in some seam cells, and dark bars indicate that GFP signals were observed in all seam cells. Each number in parentheses presents the number (n) of observed animals in each experiment. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Results

nhr-25 is required for apl-1 expression in seam cells

Our previous work had demonstrated that the expression of apl-1 in seam cells is tightly regulated and repressed by the let-7 family miRNAs after the L4 stage (Niwa et al., 2008). This repression is controlled by heterochronic genes that act downstream of let-7, such as hbl-1, lin-41, and lin-42, but not lin-29. The expression of apl-1 in seam cells is strongly induced only at the L4/Ad transition, as no or weak apl-1 expression is detected in seam cells from L1 to early L4 stages (Fig. S1) (Niwa et al., 2008). Therefore, we utilized apl-1 expression as a new approach to elucidate let-7-dependent terminal differentiation pathways at the L/A transition in C. elegans (Niwa et al., 2008). We performed an RNAi screen to search for genes that affected apl-1::gfp expression in an integrated transgenic line carrying the full length apl-1 promoter region (−6997 to −1 bp) upstream of a gfp construct (Niwa et al., 2008). We targeted 387 predicted C. elegans transcription factors (Table S1) using a subset of commercially available Ahringer’s RNAi library (Fraser et al., 2000). In the RNAi screen, we found that apl-1::gfp expression in seam cells in the L4 stage was greatly reduced by RNAi against the nhr-25 gene, which encodes an evolutionarily conserved NR from cnidarians to human (Asahina et al., 2000; Escriva et al., 1997; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000) (Figs. 1A, B and S2A, B). While apl-1::gfp expression in seam cells in the L4 stage was also reduced by RNAi against three additional transcription factor genes, nhr-195, elt-2 and lin-11 (Table S1), we did not observe any other heterochronic phenotypes, including changes in timing of alae formation and adult-specific collagen gene expression, by RNAi against any of these three genes (data not shown). Therefore, we focused on the nhr-25 gene for detailed analysis as described below.

The apl-1 reduction phenotype described above was specific to nhr-25(RNAi) and was not an off-target effect because apl-1 expression in seam cells in the late L4 stage was also diminished in the nhr-25(ku217) mutant (Fig. 1D), a hypomorphic recessive allele of nhr-25 that causes an amino acid substitution in the DNA binding domain of NHR-25 (Chen et al., 2004). nhr-25(RNAi) and nhr-25(ku217) did not affect apl-1 expression in pharyngeal cells, in which constant apl-1 expression was observed throughout development in wild-type worms (Fig. S3) (Niwa et al., 2008). While a slight decrease of the apl-1 expression level was observed in uterine pi cells in the nhr-25(RNAi) worms at the late L4 stage as compared to wild type (Fig. S3), a dramatic reduction of apl-1 expression was only detected in seam cells.

The genome of C. elegans is predicted to encode 284 NRs (Gissendanner et al., 2004; Magner and Antebi, 2008). Besides nhr-25, the daf-12 and nhr-23 NRs have also been previously shown to play a crucial role in differentiation and gene expression in seam cells (Brooks et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2006; Kostrouchova et al., 1998; Kostrouchova et al., 2001). Therefore, we examined whether the loss of nhr-23 or daf-12 function influenced apl-1 expression in seam cells during L4. RNAi against mock, nhr-23 or daf-12 showed no obvious changes in temporal apl-1::gfp expression in seam cells (Figs. 1A, C, D and S4), while nhr-23(RNAi) resulted in molting defects and daf-12(RNAi) suppressed the vulval bursting phenotype of the let-7 mutant as previously reported (Grosshans et al., 2005; Kostrouchova et al., 1998) (See Materials and Methods). These results show that NHR-25 is the major transcriptional regulator that positively controls apl-1 expression in the late L4 stage.

nhr-25 and apl-1 are synergistically required for molting

apl-1 is involved in the molting process in C. elegans (Hornsten et al., 2007; Niwa et al., 2008). Because nhr-25 is also required for C. elegans molting (Asahina et al., 2000; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000; Hayes et al., 2006), we examined whether nhr-25 genetically interacts with apl-1 to regulate molting. nhr-25(ku217); apl-1(RNAi) double mutants showed a growth defect during the L4 stage and typically could not shed their larval cuticle at the L4 molt (Fig. 2A, B), whereas nhr-25(ku217) or apl-1(RNAi) alone only rarely showed the phenotype (Fig. 2B). This genetic interaction was similar to the previously reported interaction of apl-1 with hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 (Niwa et al., 2008). We have also examined a possible genetic interaction of apl-1 and nhr-25 with lin-29 on the molting defect at L4 molt, but no obvious interactions were detected (Fig. S5).

Fig. 2. nhr-25 genetically interacts with apl-1 to regulate molting.

(A) nhr-25(ku217) animal was fed apl-1 RNAi bacteria from L1 stage. Unshed cuticle was observed at the L4 molt (arrows). Scale bar: 200 µm. (B) Percentage of animals showing the double cuticle phenotype at the L4 molt in nhr-25 mutant with mock RNAi or nhr-25(RNAi). Each number in parentheses indicates the total number of observed animals in each experiment. ***p<0.001 chi-square test.

It is known that nhr-25 and apl-1 are both required for shedding larval cuticles throughout C. elegans larval development (Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000; Hornsten et al., 2007). However, NHR-25 and APL-1 seem to be required predominantly at L4 to the adult transition, most likely apl-1 acting downstream of nhr-25, as the robust expression of apl-1 in seam cells at the late L4 stage is regulated by NHR-25 (Fig. 1A, B, D) and their loss of functions mutually enhance the L4 molting defect.

nhr-25 synergistically acts with hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 to negatively regulate the expression of adult-specific collagen gene col-19

nhr-25 appears to be directly targeted by the let-7 miRNA and its family member mir-84, and let-7-dependent repression of nhr-25 in the adult stage is essential for inhibiting the molting process characteristic of larvae (Hayes et al., 2006). Meanwhile, hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42, the heterochronic genes essential for adult differentiation in seam cells, are also downstream of let-7 (Abrahante et al., 2003; Banerjee et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2003; Slack et al., 2000). Our previous study revealed that hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 positively regulate apl-1 expression in seam cells in the late L4 stage (Niwa et al., 2008). Therefore, the positive regulation of apl-1 expression by nhr-25 in seam cells described above prompted us to investigate whether loss of nhr-25 function caused heterochronic phenotypes in seam cells. We first examined the hypodermal expression pattern of col-19, encoding an adult-specific collagen protein. col-19 is known to be a direct target of the heterochronic transcription factor LIN-29 (Abrahante et al., 1998; Rougvie and Ambros, 1995). In wild type or control (mock) RNAi animals, col-19 expression begins at mid-late L4 stage at low levels (Figs. 3A, F and S6). In contrast, similar to the depletion of hbl-1, lin-41 or lin-42 (Abrahante et al., 2003; Jeon et al., 1999) (data not shown), nhr-25(RNAi) or the nhr-25(ku217) mutation triggered strong col-19::gfp expression in the mid L4 stage (Figs. 3B and S7A) with high penetrance (Fig. 3F). nhr-23(RNAi) did not induce such col-19 expression (Figs. 3F and S7B). This induction of col-19::gfp by nhr-25(RNAi) in the mid L4 stage was not suppressed by the lin-29 loss-of-function mutation (Fig. 3F), suggesting that nhr-25 regulates col-19 expression independently from lin-29.

Fig. 3. nhr-25 acts synergistically with hbl-1, lin-41, and lin-42 to inhibit col-19 expression in L4 stage.

(A–E) Animals showing adult specific collagen col-19::gfp expression in the L4 stage of wild type (A–C) and hbl-1(mg285) mutants (D, E) with control (mock) RNAi (A, C) and nhr-25 RNAi (B, C, E). Mid L4 animals are shown in A and B, and early L4 animals are shown in C–E. Each box in the DIC image indicates the head region where the col-19::gfp signal is represented. In DIC images, arrows and arrowheads point to gonadal distal tip cells and vulva, respectively. Scale bar: 30 µm for GFP images and 100 µm for DIC images. (F) Percentage of animals showing col-19::gfp expression in mid L4 stage in the heterochronic mutants and nhr-25 (ku217) mutant. (G) Percentage of animals showing col-19::gfp expression in the early L4 stage in heterochronic mutants with mock RNAi or nhr-25 RNAi. Each number in parentheses indicates the total number of observed animals in each experiment. ***p<0.001 chi-square test.

We further examined whether nhr-25 showed a genetic interaction with hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 to regulate col-19 expression. Single depletion of nhr-25, hbl-1, lin-41, or lin-42 induced a high level of the col-19 expression after the mid L4 stage (Figs. 3B, F and S7A) but only a subtle level of the col-19 expression in the early L4 stage (Fig. 3C, D, G) (Niwa et al., 2008). In contrast, a combination of nhr-25 RNAi with either an hbl-1, lin-41, or lin-42 loss-of-function mutation dramatically increased the col-19::gfp expression in seam cells in the early L4 stage (Fig. 3E, G). These results suggest that nhr-25 synergistically acts with hbl-1, lin-41, and lin-42 to negatively regulate col-19 expression.

nhr-25 is required for precocious apl-1 expression in seam cells in hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 mutants

Although hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 positively regulate apl-1 expression in the late L4 stage as we have reported previously (Niwa et al., 2008), these genes also play a role in the negative regulation of apl-1 expression in the early L4 stage or earlier. apl-1 expression starts from the mid L4 stage in wild-type worms, and loss of function of hbl-1, lin-41 or lin-42 causes precocious apl-1 expression in the early L4 stage (Figs. 1E, H and S2C) (Niwa et al., 2008). We examined whether the precocious apl-1 expression in the early L4 stage induced by these heterochronic mutations required nhr-25 activity. As compared to mock RNAi (Figs. 1E and S2C), nhr-25(RNAi) greatly suppressed the precocious apl-1 expression in seam cells in hbl-1(mg285) (Figs. 1F, H and S2D), lin-42(n1089) (Fig. 1H; data not shown) and lin-41(ma104) mutants (data not shown). This suppression was specific to nhr-25(RNAi), as the negative control nhr-23(RNAi) did not induce any change in apl-1 expression in seam cells (Fig. 1G, H). These results suggest that nhr-25 regulates apl-1 expression downstream of hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42, and also indicate that nhr-25 counteracts hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 to control apl-1 expression in the early L4 stage. The action of nhr-25 in early L4 is opposite and paradoxical to the fact that nhr-25, hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 cooperate to positively induce apl-1 expression in the late L4 stage.

nhr-25 antagonizes the functions of hbl-1, lin-41, and lin-42 to positively regulate adult alae formation and seam cell fusion

The previous data imply that the genetic relationship between nhr-25 and other heterochronic genes is not uniform. The inconsistency of these genetic relationships prompted us to examine whether and how nhr-25 regulates adult differentiation programs apart from col-19 expression. First, we examined whether nhr-25 is involved in the temporal control of adult alae formation, which is an adult-specific cuticular structure secreted from seam cells (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984). Whereas loss of nhr-25 function has been previously reported to cause abnormal adult alae morphology (Silhankova et al., 2005), genetic interactions between nhr-25 and heterochronic genes have not been elucidated. Adult alae formation is temporally regulated by hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42, as loss-of-function mutations of these genes cause precocious alae formation in the early L4 stage (Fig. 4A, B, D) (Abrahante et al., 2003; Abrahante et al., 1998; Jeon et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2003; Slack et al., 2000). Our above-described result about col-19 expression implied that the precocious alae formation in the absence of either hbl-1, lin-41 or lin-42 function should also be enhanced by nhr-25(RNAi). However, nhr-25(RNAi) significantly suppressed the precocious alae formation in these mutant backgrounds (Fig. 4C, D), and no precocious alae defect was observed in nhr-25(RNAi) alone (Fig. 4D). It is noteworthy that the penetrance of precocious alae phenotypes was much higher than that of col-19 expression (Fig. 3G) in the early L4 stage of hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 mutants. These results suggest that the timing of expression of precocious phenotypes are independent between alae formation and col-19 expression in seam cells, or reflect a delay in GFP accumulation.

Fig. 4. Precocious alae formation is suppressed by nhr-25 RNAi in the heterochronic mutants.

(A–C) Scanning electron micrographs of precocious alae in early L4 animals of wild type N2 with control (mock) RNAi (A), hbl-1(ve18) mutant with mock RNAi (B) and hbl-1(ve18) mutant with nhr-25 RNAi (C) in the early L4 stage. In wild type, adult alae were not observed in L4 animals (A). The precocious alae in hbl-1 mutant (B) were suppressed by nhr-25 RNAi (C). Arrowheads indicate alae. Scale bar: 5 µm. (D) Percentage of animals showing precocious alae formation in the L4 stage. Each number in parentheses indicates the number (n) of observed animals in each sample. ***p<0.001 chi-square test.

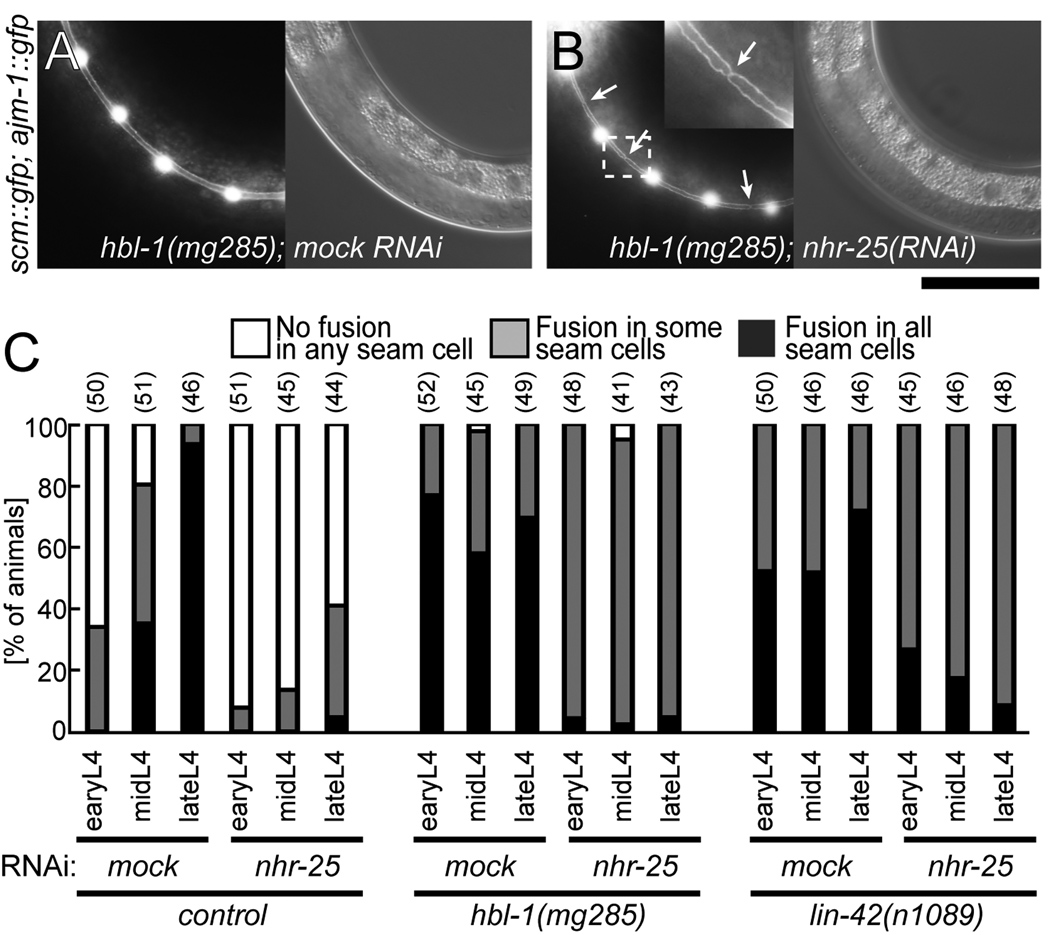

We also examined whether the activity of nhr-25 modulated the timing of seam cell fusion. In wild type animals, seam cells divide with a stem cell-like pattern during larval stages before exiting the cell cycle, and these cells terminally differentiate and fuse each other around the time of the L4 molt (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977). In addition to abnormal adult alae formation, loss-of-function mutations of hbl-1 and lin-42 precociously induce the seam cell fusion even in the early L4 stage (Fig. 5A, C) as compared to wild-type worms (Figs. 5C and S8A) (Abrahante et al., 2003; Banerjee et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2003). In contrast, nhr-25(RNAi) decreased the numbers of individual worms exhibiting precociously fused seam cells in hbl-1 and lin-42 mutants in the early L4 stage (Fig. 5B, C) but did so less efficiently than mutations of the master adult switch gene lin-29 (Abrahante et al., 2003; Abrahante et al., 1998; Jeon et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2003). nhr-25(RNAi) itself also prevented seam cell fusion in the late L4 stage (Figs. 5C and S8B). These results suggest that nhr-25 is negatively regulated by and acts antagonistically to hbl-1 and lin-42 during seam cell fusion as well as adult alae formation.

Fig. 5. Precocious seam cell fusion is suppressed by nhr-25 RNAi in the heterochronic mutants.

Seam cell junctions were visualized in the integrated GFP strain wIs79 containing both ajm-1::gfp and scm::gfp. (A) hbl-1(mg285); wIs79 animals had precocious fused seam cells in the early L4 stage as indicated by lack of AJM-1::GFP signal at cell junctions. (B) hbl-1 (mg285); nhr-25 RNAi animals had unfused seam cells in the early L4 stage as indicated by GFP signal at the cell junctions (arrows). Inset is a higher magnification picture corresponding to the region marked by dashed box. Scale bar: 100 µm. (C) Temporal profiles of seam cell fusion in the L4 stage in heterochronic mutants with or without nhr-25 RNAi. Open bars indicate that any fusion in seam cells was not observed, shaded bars indicate that some seam cells fused, and dark bars indicate that all seam cells fused. Each number in parentheses presents the number (n) of each sample.

The data of the alae formation and seam cell fusion were somewhat puzzling, considering that the double mutants appear to express the col-19::gfp reporter in the early L4 stage. A potential explanation is that NHR-25 is also required for protein synthesis and/or secretion of COL-19 in addition to col-19 expression. Therefore, we examined the protein level and distribution of the COL-19 proteins using an integrated array expressing COL-19::GFP translational fusion construct (Thein et al., 2003). Indeed, we observed no precocious the COL-19::GFP signals in nhr-25(RNAi) L4 animals (data not shown). This observation may imply the posttranscriptional regulation of COL-19 in the L/A transition.

lin-29 is required for nhr-25 expression in the late L4 stage

During adult alae formation and seam cell fusion, the action of nhr-25 resembles that of lin-29, which positively regulates the L/A transition (Rougvie, 2005; Rougvie and Ambros, 1995). We therefore examined whether there is a genetic interaction between nhr-25 and lin-29. In experimental conditions using nhr-25(RNAi) bacteria diluted with an equal volume of mock RNAi to provide a lower intensity of RNAi, a small percentage of nhr-25 or lin-29 RNAi animals displayed retarded alae formation and retarded seam cell fusion at the young adult stage (Fig. 6A, B). In contrast, we found a synergistic effect of nhr-25 and lin-29 on alae formation and seam cell fusion, as simultaneous RNAi against both nhr-25 and lin-29 with the same experimental condition gave rise to significant numbers of animals exhibiting retarded phenotypes in seam cells (Fig. 6A, B). This finding suggests that nhr-25 and lin-29 play overlapping roles in the same, or parallel, pathways to affect the L/A transition.

Fig. 6. nhr-25 interacted with and is in part transcriptionally regulated by lin-29.

(A, B) Synergistic genetic interactions between nhr-25 and lin-29 for controlling adult alae formation and seam cell fusion. Percentages of animals without complete, normal alae structure (A) and of animals not showing normal seam cell fusion (B) in nhr-25 RNAi, lin-29 RNAi and lin-29;nhr-25 double RNAi animals at young adult stages. For B, cell junctions were visualized using the wIs79 strain. Each number in parentheses presents the number of each sample. nhr-25 and lin-29 RNAi bacteria were doubly diluted with an equal volume of mock RNAi to provide a lower intensity of RNAi. To statistically examine a synergistic interaction between nhr-25 and lin-29, chi-square test was performed comparing between data of lin-29;nhr-25 double RNAi and a summation of data of nhr-25 RNAi alone and lin-29 RNAi alone. (C) Temporal expression profiles of the extrachromosomal nhr-25::gfp::unc-54 lines with control (mock) and lin-29 RNAi in early, mid, and late L4 stages. nhr-25 expression in seam cells was significantly reduced in lin-29 RNAi animals in the late L4 stage, but not earlier. ***p<0.001 chi-square test.

We also examined nhr-25 expression levels using a transgenic line carrying a transcriptional gfp fusion with the nhr-25 promoter (Silhankova et al., 2005). We found that nhr-25::gfp expression was moderately but significantly reduced in seam cells in lin-29(RNAi) animals in the late L4 stage but not earlier (Fig. 6C), suggesting that lin-29 partially promotes nhr-25 expression in seam cells.

nhr-25 and hbl-1 mutually inhibit each other in controlling seam cell proliferation

A more complicated genetic relationship between nhr-25 and hbl-1 was observed in developmental timing of seam cell division. As previously reported (Chen et al., 2004; Silhankova et al., 2005), nhr-25(RNAi) animals exhibited an increased number of seam cell nuclei as compared to wild-type animals at the adult stage (Figs. 7A, B and S9A, B). However, the number of seam cells was not increased in nhr-25(RNAi) animals in the early L4 stage in our conditions (Fig. S10A, B). These data suggest that NHR-25 normally represses seam cell proliferation in the L/A transition, and thus, the seam cell number defect of nhr-25(RNAi) young adults resembled the retarded let-7 mutants (Reinhart et al., 2000). Similar to loss of nhr-25 function worms, hbl-1 mutations caused seam nuclei to divide inappropriately in the late L4, but not early L4 stages as also previously reported (Figs. 7C, S9C and S10C) (Abrahante et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2003). Unexpectedly, young adults with depletion of both nhr-25 and hbl-1 function exhibited an almost normal seam cell number (Figs. 7D and S9D). This result implies that nhr-25 and hbl-1 mutually suppress each other to control seam cell proliferation in the L/A transition. Although the superficial phenotype of the loss of nhr-25 or hbl-1 function worm suggests at repressive role in seam cell division in the L/A transition, nhr-25 and hbl-1 are indeed positive regulators for seam cell division in the L/A transition.

Fig. 7. nhr-25 acts with hbl-1 to control seam cell division.

Seam cell nuclei were visualized and scored by an integrated GFP strain wIs51[scm::gfp]. Seam cell nuclei were counted on one side of animals at the young adult stage (48 hours after hatching). Average numbers of seam cells (± S.D.) are also shown. X-axis is the number of seam cell nuclei, and y-axis is the number of animals. Each genotype is indicated in its panel.

Discussion

Identification of nhr-25 as a heterochronic gene modulator

We show in this study that the evolutionarily conserved nuclear receptor NHR-25 (Asahina et al., 2000; Escriva et al., 1997; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000) is required to regulate the L/A transition in C. elegans. Based upon the mixed phenotypes of loss of nhr-25 function animals, which exhibit both retarded and precocious characteristics, we conclude that nhr-25 is a novel heterochronic gene modulator essential for both promoting and preventing terminal differentiation of seam cells (Fig. 8). Our results imply that the L/A transition is not mediated by a simple cascade of heterochronic genes. Rather, each adult differentiation event is controlled by a cascade that has a genetic network distinct from other cascades, even though each cascade consists of similar sets of heterochronic genes. Thus, the molecular mechanism of developmental timing involves an unexpected complexity.

Fig. 8. nhr-25 has a dual role in regulating the L/A transition.

nhr-25 negatively regulates apl-1 expression at the L/A transition (A-1, A-2). Our data suggest that nhr-25 regulates apl-1 downstream of hbl-1, lin-41 and lin-42 in the early L4 stage (A-1), while nhr-25 regulates apl-1 in parallel to these heterochronic genes in the late L4 stage (A-2). The nhr-25-mediated apl-1 expression in the late L4 stage is required for molting at the L/A transition. nhr-25 also negatively regulates col-19 expression in the L4 stage, while nhr-25 seems to positively regulate col-19 expression in the adult stage (B). At the same time, nhr-25 also positively regulates alae formation and seam cell fusion at the L/A transition. (C). In this case, nhr-25 is activated by lin-29 in part at the transcription level. However, in the case of D, nhr-25 and hbl-1 mutually suppress each other to control seam cell proliferation during the L/A transition, whereas nhr-25 and hbl-1 themselves indeed are positive regulators of seam cell division at the L/A transition (D). It is noteworthy that the epistatic relationships between nhr-25 and other heterochronic genes are diverse among adult differentiation programs.

Previous studies have demonstrated that loss of nhr-25 function causes various phenotypes throughout development, such as defects on embryogenesis, differentiation of larval epidermis, molting, distal tip cell/anchor cell formation, and cell-cell fusion in vulval morphogenesis (Asahina et al., 2000; Asahina et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2004; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000; Hajduskova et al., 2009; Silhankova et al., 2005). These observed phenotypes are the result of earlier or very severe knock-down and may have masked later or alternative functions. By contrast, our study clearly demonstrates genetic interactions between nhr-25 and several heterochronic genes that have not previously been detected. It is possible that the penetrance and/or timing of the nhr-25(RNAi) in this work does not severely alter the vital development outcomes associated with earlier developmental defects that were previously reported (Asahina et al., 2000; Asahina et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2004; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000; Hajduskova et al., 2009; Silhankova et al., 2005). We posit that the relatively weak RNAi conditions used in this study may have allowed us to uncover a novel developmental timing function of nhr-25. However, because this study involves hypomorphic alleles or RNAi of hbl-1, lin-41, lin-42 and nhr-25, the interpretations of genetic relationships that we propose must be studied further.

Possible coupling of molecular mechanisms of developmental timing and molting

Molting is another major developmental timing landmark in the ecdysozoan life cycle. In addition to the essential role of nhr-25 in the heterochronic gene network that we demonstrate in this study, nhr-25 has a function in controlling C. elegans molting (Asahina et al., 2000; Frand et al., 2005; Gissendanner and Sluder, 2000). Our data suggest that the nhr-25-dependent molting process in the L/A transition requires the epidermal expression of apl-1, which is also known to be involved in C. elegans molting (Hornsten et al., 2007; Niwa et al., 2008). However, a previous report has indicated that apl-1 expression in the nervous system, rather than the epidermis, is sufficient for molting in the L1-to-L2 transition (Hornsten et al., 2007). Whereas the reason for the discrepancy is not yet understood, it is possible that the molting processes in different developmental stages need apl-1 expression in different types of cells.

Known canonical heterochronic mutations affect neither larval growth nor progression through the molting cycle in C. elegans, even though individual hypodermal blast cells have the incorrect temporal identity (Ambros and Horvitz, 1984; Moss, 2007). Therefore, two independent timers have been proposed: one to control temporal boundaries of development such as molting and the other to regulate temporal identities such as stage-specific patterns of cell division and differentiation (Thummel, 2001). This view has been strengthened by recent reports that a combination of let-7 family miRNA mutations exhibits only an extra molting phenotype but not an aberrant cell fate defect in the adult stage (Abbott et al., 2005; Hayes et al., 2006). Another piece of evidence supporting this view is that illegitimate activation of nicotinic receptor nAChRs during the second larval stage induces a lethal heterochronic phenotype by slowing developmental speed without affecting the molting timer (Ruaud and Bessereau, 2006). Controversially, our present study implies that one genetic component, nhr-25, participates in the regulation of both heterochronic temporal identity and molting in the L/A transition. More work is necessary to determine how the temporal identity conferred by the heterochronic genes is related to molting, for example through the identification of downstream target genes like apl-1.

NHR-25 can regulate the L/A transition in versatile ways

nhr-25 negatively regulates certain events in the L/A transition, such as expression of the adult-specific collagen gene col-19 and seam cell division as well as larval molting programs in the adult stage (Hayes et al., 2006). In the same animals, nhr-25 also positively controls adult differentiation programs, including seam cell fusion and alae formation. Genetic relationships between nhr-25 and other heterochronic genes are also diversified among adult differentiation programs, as summarized in Fig. 8.

How does NHR-25 accomplish these complicated interactions with other heterochronic genes (i.e., hbl-1, lin-41, and lin-42) to mediate the L/A transition within the same seam cells of the same animals? These interactions cannot be explained by simple temporal changes of transcriptional and/or translational regulation of identified heterochronic genes themselves, as nhr-25 controls the developmental timing of col-19 expression, seam cell division, seam cell fusion, and alae formation, all of which occur in the same seam cells. For example, although our data indicate that the nhr-25 transcription level is influenced by the activity of lin-29 (Fig. 6C), this effect can only account for the epistasis of lin-29 to nhr-25 for apl-1 expression in the early L4 stage, alae formation, and seam cell fusion (Fig. 8C) and cannot explain the regulation of other adult differentiation programs (Fig. 8A1, A2, B). We also observed no obvious difference in GFP signals derived from nhr-25::gfp::unc-54 transgenic lines between control and hbl-1(RNAi) animals (Fig. S11).

Alternatively, a possible explanation for the complexity of nhr-25 genetic functions is that a specific protein could physically interact with NHR-25 to control each adult differentiation event. Like other NRs, the Ftz-F1/SF-1 family proteins physically interact with transcriptional coactivators and DNA-binding transcription factors (Pick et al., 2006). In C. elegans, direct physical and genetic interactions have been reported between NHR-25 and two Hox proteins, LIN-39 and NOB-1. Mutations in these genes display vulval phenotypes similar to nhr-25 mutants (Chen et al., 2004). In the gonadal precursor cells, the physical interaction between NHR-25 and C. elegans β-catenins, WRM-1 and SYS-1, is important to modulate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Asahina et al., 2006). Because the specific interaction between Ftz-F1/SF-1 and the binding partners may explain the spatial- and/or temporal-specific function of Ftz-F1/SF-1 (Pick et al., 2006), NHR-25 may have a certain binding partner that directs gene expression by itself and/or modulates the protein subcellular localizations for each adult differentiation program. Identifying potential binding partners for NHR-25 in seam cells would shed light on how NHR-25 has a variety of roles among different adult differentiation programs.

Insect Ftz-F1 and developmental timing

Interestingly, βFtz-F1, an insect ortholog of nhr-25, has been extensively studied in terms of how it regulates the timing of insect developmental processes such as molting and metamorphosis (Thummel, 2001). In insects, pulses of the steroid hormone ecdysone and its relative 20-hydroxyecdysone control transitions between life stages. These insects go through molting by activating stage-specific transcriptional cascades involving several NRs, including Ecdysone receptor and Ultraspiracle, which together form the receptor for 20-hydroxyecdysone, as well as DHR3, DHR38 and βFtz-F1 (Thummel, 2001). nhr-23, an ortholog of insect DHR3, and nhr-25 have been directly linked with C. elegans molting (Asahina et al., 2000; Frand et al., 2005; Kostrouchova et al., 1998).

Drosophila ftz-f1 is also required for proper embryonic segmentation. Alternate segments are deleted in ftz-f1 mutant embryos in a pair-rule fashion, as they are in mutants for the homeodomain protein Fushi tarazu (Ftz), with which Ftz-F1 interacts (Pick et al., 2006). Previous studies have indicated that spatial embryonic patterning in Drosophila segmentation and temporal patterning in seam cells of C. elegans share key conserved genes. For example, C. elegans hbl-1 is an ortholog of Drosophlila hunchback (hb). Interestingly, hb is best known for its essential role in spatial patterning in the Drosophila embryonic anterior and is also known to regulate temporal neuroblast identity (Isshiki et al., 2001; Rougvie, 2005). Furthermore, a recent study has shown that loss of Drosophila squeeze, a Drosophila homolog of the heterochronic gene lin-29, causes a temporal identity defect in Drosophila neuroblast (Tsuji et al., 2008). By analogy with these conserved heterochronic genes, it would be intriguing to investigate if ftz-f1 is involved in the timing regulation of Drosophila neuroblast. It is noteworthy that ftz is expressed in a subset of Drosophila embryonic neurons (Doe, 1992).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Victor Ambros, Andrew Fire, Christopher Hammell and Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for stocks and reagents; Aurora Esquela-Kerscher and Damien Hall for critical reading of this manuscript; Yoshihiro Shiraiwa, Katsuo Furukubo-Tokunaga, and Yusuke Kato for allowing K.H. and R.N. to use their space and equipment, and Electron Microscopy facility of Biology Centre for technical assistance. R.N. was a recipient of a fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program Organization. This work was supported in part by Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of the Japanese Government. This work was also supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI; 20870005 and 22770207) to R.N.; grants GACR 204/07/0948 and 204/09/H058 (Czech Science Foundation) and Z60220518 to M.A.; and grants to F.J.S. from the Ellison Medical Foundation and NIH (GM64701).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott AL, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Miska EA, Lau NC, Bartel DP, Horvitz HR, Ambros V. The let-7 MicroRNA family members mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 function together to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell. 2005;9:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahante JE, Daul AL, Li M, Volk ML, Tennessen JM, Miller EA, Rougvie AE. The Caenorhabditis elegans hunchback-like gene lin-57/hbl-1 controls developmental time and is regulated by microRNAs. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahante JE, Miller EA, Rougvie AE. Identification of heterochronic mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Temporal misexpression of a collagen::green fluorescent protein fusion gene. Genetics. 1998;149:1335–1351. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. Control of developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000;10:428–433. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V, Horvitz HR. Heterochronic mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1984;226:409–416. doi: 10.1126/science.6494891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina M, Ishihara T, Jindra M, Kohara Y, Katsura I, Hirose S. The conserved nuclear receptor Ftz-F1 is required for embryogenesis, moulting and reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Cells. 2000;5:711–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina M, Valenta T, Silhankova M, Korinek V, Jindra M. Crosstalk between a nuclear receptor and beta-catenin signaling decides cell fates in the C. elegans somatic gonad. Dev. Cell. 2006;11:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Kwok A, Lin SY, Slack FJ. Developmental timing in C. elegans is regulated by kin-20 and tim-1, homologs of core circadian clock genes. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D, Slack F. Control of developmental timing by small temporal RNAs: a paradigm for RNA-mediated regulation of gene expression. Bioessays. 2002;24:119–129. doi: 10.1002/bies.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke A, Fielenbach N, Wang Z, Mangelsdorf DJ, Antebi A. Nuclear hormone receptor regulation of microRNAs controls developmental progression. Science. 2009;324:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1164899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger JC, Lee K, Rougvie AE. Stage-specific accumulation of the terminal differentiation factor LIN-29 during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Development. 1996;122:2517–2527. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DR, Appleford PJ, Murray L, Isaac RE. An essential role in molting and morphogenesis of Caenorhabditis elegans for ACN-1, a novel member of the angiotensin-converting enzyme family that lacks a metallopeptidase active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52340–52346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Eastburn DJ, Han M. The Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear receptor gene nhr-25 regulates epidermal cell development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:7345–7358. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7345-7358.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe CQ. Molecular markers for identified neuroblasts and ganglion mother cells in the Drosophila central nervous system. Development. 1992;116:855–863. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escriva H, Safi R, Hanni C, Langlois MC, Saumitou-Laprade P, Stehelin D, Capron A, Pierce R, Laudet V. Ligand binding was acquired during evolution of nuclear receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6803–6308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquela-Kerscher A, Johnson SM, Bai L, Saito K, Partridge J, Reinert KL, Slack FJ. Post-embryonic expression of C. elegans microRNAs belonging to the lin-4 and let-7 families in the hypodermis and the reproductive system. Dev. Dyn. 2005;234:868–877. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand AR, Russel S, Ruvkun G. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans molting. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Zipperlen P, Martinez-Campos M, Sohrmann M, Ahringer J. Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature. 2000;408:325–330. doi: 10.1038/35042517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissendanner CR, Crossgrove K, Kraus KA, Maina CV, Sluder AE. Expression and function of conserved nuclear receptor genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 2004;266:399–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissendanner CR, Sluder AE. nhr-25, the Caenorhabditis elegans ortholog of ftz-f1, is required for epidermal and somatic gonad development. Dev. Biol. 2000;221:259–272. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans H, Johnson T, Reinert KL, Gerstein M, Slack FJ. The temporal patterning microRNA let-7 regulates several transcription factors at the larval to adult transition in C. elegans. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduskova M, Jindra M, Herman MA, Asahina M. The nuclear receptor NHR-25 cooperates with the Wnt/beta-catenin asymmetry pathway to control differentiation of the T seam cell in C. elegans. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:3051–3060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.052373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammell CM, Karp X, Ambros V. A feedback circuit involving let-7-family miRNAs and DAF-12 integrates environmental signals and developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18668–18673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908131106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes GD, Frand AR, Ruvkun G. The mir-84 and let-7 paralogous microRNA genes of Caenorhabditis elegans direct the cessation of molting via the conserved nuclear hormone receptors NHR-23 and NHR-25. Development. 2006;133:4631–4641. doi: 10.1242/dev.02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsten A, Lieberthal J, Fadia S, Malins R, Ha L, Xu X, Daigle I, Markowitz M, O'Connor G, Plasterk R, Li C. APL-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans protein related to the human beta-amyloid precursor protein, is essential for viability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:1971–1976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603997104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki T, Pearson B, Holbrook S, Doe CQ. Drosophila neuroblasts sequentially express transcription factors which specify the temporal identity of their neuronal progeny. Cell. 2001;106:511–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00465-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon M, Gardner HF, Miller EA, Deshler J, Rougvie AE. Similarity of the C. elegans developmental timing protein LIN-42 to circadian rhythm proteins. Science. 1999;286:1141–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, Welchman DP, Zipperlen P, Ahringer J. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrouchova M, Krause M, Kostrouch Z, Rall JE. CHR3: a Caenorhabditis elegans orphan nuclear hormone receptor required for proper epidermal development and molting. Development. 1998;125:1617–1626. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrouchova M, Krause M, Kostrouch Z, Rall JE. Nuclear hormone receptor CHR3 is a critical regulator of all four larval molts of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7360–7365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131171898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lall S, Grun D, Krek A, Chen K, Wang YL, Dewey CN, Sood P, Colombo T, Bray N, Macmenamin P, Kao HL, Gunsalus KC, Pachter L, Piano F, Rajewsky N. A genome-wide map of conserved microRNA targets in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Jones-Rhoades MW, Lau NC, Bartel DP, Rougvie AE. Regulatory mutations of mir-48, a C. elegans let-7 family MicroRNA, cause developmental timing defects. Dev Cell. 2005;9:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SY, Johnson SM, Abraham M, Vella MC, Pasquinelli A, Gamberi C, Gottlieb E, Slack FJ. The C. elegans hunchback homolog, hbl-1, controls temporal patterning and is a probable microRNA target. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:639–650. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magner DB, Antebi A. Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear receptors: insights into life traits. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;19:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss EG. Heterochronic genes and the nature of developmental time. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R425–R434. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa R, Zhou F, Li C, Slack FJ. The expression of the Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein-like gene is regulated by developmental timing microRNAs and their targets in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 2008;315:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KK, Elks CE, Li S, Zhao JH, Luan J, Andersen LB, Bingham SA, Brage S, Smith GD, Ekelund U, Gillson CJ, Glaser B, Golding J, Hardy R, Khaw KT, Kuh D, Luben R, Marcus M, McGeehin MA, Ness AR, Northstone K, Ring SM, Rubin C, Sims MA, Song K, Strachan DP, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Waterworth DM, Wong A, Deloukas P, Barroso I, Mooser V, Loos RJ, Wareham NJ. Genetic variation in LIN28B is associated with the timing of puberty. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:843–848. doi: 10.1038/ng.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, Hayward DC, Ball EE, Degnan B, Muller P, Spring J, Srinivasan A, Fishman M, Finnerty J, Corbo J, Levine M, Leahy P, Davidson E, Ruvkun G. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick L, Anderson WR, Shultz J, Woodard CT. The Ftz-F1 family: Orphan nuclear receptors regulated by novel protein-protein interactions. Adv. Dev. Biol. 2006;16:255–296. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougvie AE. Intrinsic and extrinsic regulators of developmental timing: from miRNAs to nutritional cues. Development. 2005;132:3787–3798. doi: 10.1242/dev.01972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougvie aE, Ambros V. The heterochronic gene lin-29 encodes a zinc finger protein that controls a terminal differentiation event in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1995;121:2491–2500. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roush SF, Slack FJ. Transcription of the C. elegans let-7 microRNA is temporally regulated by one of its targets, hbl-1. Dev. Biol. 2009;334:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruaud AF, Bessereau JL. Activation of nicotinic receptors uncouples a developmental timer from the molting timer in C. elegans. Development. 2006;133:2211–2222. doi: 10.1242/dev.02392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhankova M, Jindra M, Asahina M. Nuclear receptor NHR-25 is required for cell-shape dynamics during epidermal differentiation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:223–232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack FJ, Basson M, Liu Z, Ambros V, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen JM, Gardner HF, Volk ML, Rougvie AE. Novel heterochronic functions of the Caenorhabditis elegans period-related protein LIN-42. Dev. Biol. 2006;289:30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thein MC, McCormack G, Winter AD, Johnstone IL, Shoemaker CB, Page AP. Caenorhabditis elegans exoskeleton collagen COL-19: an adult-specific marker for collagen modification and assembly, and the analysis of organismal morphology. Dev. Dyn. 2003;226:523–539. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel CS. Molecular mechanisms of developmental timing in C. elegans and Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L, Fire A. Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature. 1998;395:854. doi: 10.1038/27579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T, Hasegawa E, Isshiki T. Neuroblast entry into quiescence is regulated intrinsically by the combined action of spatial Hox proteins and temporal identity factors. Development. 2008;135:3859–3869. doi: 10.1242/dev.025189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.