Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the kinetics of change in symptoms and signs of convergence insufficiency (CI) during 12 weeks of treatment with commonly prescribed vision therapy/orthoptic treatment regimens.

Methods

In a randomized clinical trial, 221 children ages 9 to 17 years with symptomatic CI were assigned to home-based pencil push-ups (HBPP), home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups (HBCVAT+), office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with home reinforcement (OBVAT), or office-based placebo therapy with home reinforcement (OBPT). Symptoms and signs were measured following 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment. Mean CI Symptom Survey (CISS), near point of convergence (NPC), positive fusional vergence (PFV), and proportions of patients asymptomatic or classified as successful or improved based on a composite measure of CISS, NPC, and PFV.

Results

Only the OBVAT group showed significant improvements in symptoms between each visit (p-values<0.001). Between weeks 8 and 12, all groups showed a significant improvement in symptoms. Between group differences were apparent by week 8 (p=0.037) with the fewest symptoms in the OBVAT group. For each group, the greatest improvements in NPC and PFV were achieved during the first 4 weeks. Differences between groups became apparent by week 4 (p-values<0.001), with the greatest improvements in NPC and PFV in the OBVAT group. Only the OBVAT group continued to show significant improvements in PFV at weeks 8 and 12. The percentage of patients classified as “successful” or “improved” based on our composite measure increased in all groups at each visit.

Conclusions

The rate of improvement is more rapid for clinical signs (NPC and PFV) than for symptoms in children undergoing treatment for CI. OBVAT results in a more rapid improvement in symptoms, NPC and PFV, and a greater percentage of patients reaching pre-determined criteria of success when compared with HBPP, HBCVAT+, or OBPT.

Keywords: convergence insufficiency, asthenopia, vision therapy, orthoptics, vergence/accommodative therapy, pencil push-ups, computer vergence/accommodative therapy, placebo therapy, exophoria, eyestrain, symptom survey, school children

Various types of vision therapy/orthoptics are prescribed for children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency (CI). We recently completed a randomized clinical trial in which 9 to 17-year old children with symptomatic CI were randomized to a 12-week treatment program of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with home reinforcement (OBVAT), home-based pencil push-ups (HBPP), home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups (HBVCAT+), and office-based placebo therapy with home reinforcement (OBPT).1 OBVAT was found to be significantly more effective in improving symptoms and clinical signs as compared to the 2 home-based treatments and to OBPT.1 Because all treatments were successful for some patients and because the rate of improvement in symptoms and clinical signs during treatment is unknown, we evaluated the kinetics of change in symptoms and clinical signs during the 12-week treatment program for each treatment group including comparison of changes within and between groups at each visit. This report will focus on between group comparisons for the first 8 weeks of the study and within group changes that occurred during the first 12 weeks. Between group comparisons at 12 weeks have been previously reported 1 and therefore will not be described in this paper.

METHODS

The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed throughout the study. The institutional review boards of all participating centers approved the protocol and informed consent forms. The parent or guardian (subsequently referred to as “parent”) of each study patient gave written informed consent and each patient assented to participate. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization was obtained from the parent. Study oversight was provided by an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (see Appendix). This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT). The design and methods of the randomized trial have been published in separate manuscripts 1, 2 and are described briefly herein.

Major eligibility criteria for the trial included children ages 9 to 17 years who through their best refractive correction had an exodeviation at near at least 4 prism diopters (Δ) greater than at far, a receded near point of convergence (NPC) break (6 cm or greater), and insufficient positive fusional vergence (convergence amplitudes) at near (PFV) (i.e., failing Sheard’s criterion [PFV less than twice the near phoria] 3 or minimum PFV of ≤15Δ base-out blur or break), and a Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS ) score of ≥16.4, 5 Eligible patients who consented to participate were stratified by site and randomly assigned with equal probability using a permuted block design to OBVAT, HBPP, HBCVAT+, or OBPT.

Treatments

All methods have been described previously in detail. 6 In brief, the home-based pencil push-ups group was prescribed 15 minutes of pencil push-ups for 5 days per week using small letters on a pencil as the target and a physiological diplopia awareness control. Patients assigned to the home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups therapy group were prescribed 15 minutes of therapy per day on the Home Therapy System (HTS/CVS) (www.visiontherapysolutions.com) computer software and 5 minutes per day of pencil push-ups for 5 days per week. The computerized therapy consisted of fusional vergence and accommodative therapy procedures including accommodative rock (facility), vergence base in, vergence base out, auto-slide vergence, and jump ductions vergence programs using random dot stereopsis targets. The office-based VT/orthoptics group received a weekly 60-minute in-office therapy visit with additional home therapy procedures prescribed for 15 minutes a day, 5 days per week. Therapy consisted of a specific sequence of standard vergence and accommodative procedures. 6,7 Patients in the office-based placebo therapy group also received therapy during a weekly 60-minute office visit and were prescribed procedures to be performed at home for 15 minutes per day, 5 days per week; however, their therapy procedures were designed to resemble real vergence/accommodative therapy procedures yet not stimulate vergence, accommodation, or fine saccadic eye movement skills beyond normal daily visual activities. 8

Outcome Measures

For the clinical trial, the primary outcome measure was the change in the CISS score from baseline to treatment completion after 12 weeks of therapy; and the secondary outcome measures were the change in NPC and in PFV from baseline to treatment completion. Certified examiners who were masked to the patients’ treatment assignment administered the CISS and measured the NPC and PFV at the conclusion of the 12-week therapy program and also at protocol-specified visits that occurred following 4 and 8 weeks of therapy. Henceforth, these masked study visits are referred to as week 4, week 8, and week 12 exams.

The CISS, described in detail previously, 4, 5, 9 is a questionnaire consisting of 15 items pertaining to symptoms experienced by the child when reading or doing close work. A CISS score of less than 16 was classified as “asymptomatic” and a decrease of 10 or more points was “improved”.5, 9 A “normal” NPC was defined as less than 6 cm and an “improved” NPC was defined as an improvement (decrease) of more than 4 cm from baseline. A “normal” PFV was meeting Sheard’s criteria (i.e., PFV blur [or break, if no blur] value at least twice the near phoria magnitude) and a PFV blur/break of more than 15Δ. An “improved” PFV was an increase of 10Δ or more from baseline.

A composite measure of both symptoms and signs (CISS, NPC and PFV) was used to classify treatment outcome as successful, improved, or nonresponsive to treatment (i.e., a nonresponder). A “successful” outcome was defined as a CISS score of <16 and achievement of both a normal NPC and PFV. Treatment outcome was considered “improved” when the CISS score was <16 or there was a 10-point decrease from baseline, and one or more of the following were present: a normal NPC, improvement in NPC of greater than 4 cm from baseline, a normal PFV, or a 10Δ or greater increase in PFV from baseline. Patients who did not meet the criteria for a “successful” or “improved” outcome were considered “non-responders.” The proportion of patients who were classified as successful or improved was determined for the 4-, 8-, and 12-week examinations.

Statistical Methods

Data analyses were performed using intention to treat methodology. No imputation methods were employed to account for missing data. Comparisons of the mean outcome at weeks 4 and 8 were performed using the same analysis technique that was used to compare the means at week 12 in a previously published manuscript.1 For these comparisons, a 4 treatment group by 3 time point (visit) repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare the treatments while adjusting for any differences at baseline. Comparisons of the mean change across time within treatment groups was performed using a 4 treatment group by 4 time point (visit) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Both analysis methods allow for the inclusion of patients with incomplete data (i.e., missed study visits). P-values from the post-hoc pair-wise comparisons were adjusted using Sidak’s method.10 Chi-square statistics were used to assess the relationship between categorical measures of outcome (e.g., the percentage of children asymptomatic or improved) and treatment. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Two hundred and twenty-one children ages 9 to 17 years with symptomatic CI were enrolled in the study. Baseline demographic and clinical data collected at baseline have been published previously.2 Retention in the study was excellent (99%) and less than 2% of all study visits (therapy visits and examinations) were missed. Three children missed their week 4 examination (1 HBPP, 1 HBCVAT+, 1 OBVAT), all children were examined at week 8, and 2 children (1 HBPP, 1 OBVAT) missed their week 12 examination.

Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey (CISS)

Within Group Comparisons: Change in the CISS Between Exams for each Treatment Group

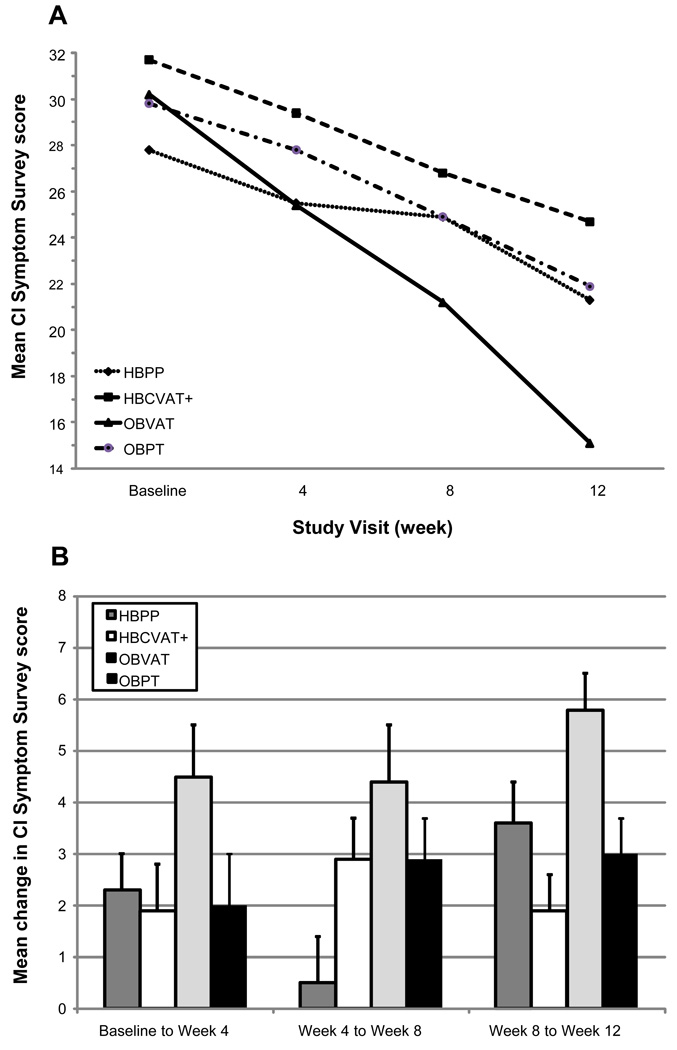

The mean (SD) CISS scores at baseline and the 4-, 8-, and 12-week examinations for the 4 treatment groups are provided in Table 1 and displayed graphically in Figure 1A. The CISS score decreased (improved) over time in each of the four treatment groups; however, the rate of change was not consistent across groups (p < 0.001). Table 2 provides the pair-wise comparisons of the mean CISS scores at subsequent visits (from baseline to week 4, from week 4 to week 8, and from week 8 to week 12) for treatment group and Figure 1B displays the changes between visits graphically. After 4 weeks of therapy, the OBVAT group showed a significant (p<0.001) improvement in symptoms while the HBCVAT+ and OBPT did not (p=0.11 and 0.10, respectively). Although statistically significant (p=0.045), the change in the HBPP group was small and similar to that of the HBCVAT+ and OBPT groups. As seen in Table 2 and Figure 1B, all but the HBPP group showed significant changes in their CISS scores between the week-4 and week-8 examinations. Between weeks 8 and 12, all groups showed a significant improvement in their CISS scores. The largest between-visit mean change in CISS score was 5.8 points and occurred in the OBVAT group between the 8- and 12-week visits.

Table 1.

Mean response and 95% confidence interval for each outcome measure at baseline and the 4-, 8-, and 12- week examinations, by treatment group.

| HBPP (n=54) | HBCVAT+ (n=53) | OBVAT (n=60) | OBPT (n=54) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |

| CI Symptom Survey score | ||||||||

| Baseline | 27.8 | 25.8, 29.8 | 31.7 | 29.3, 34.1 | 30.2 | 27.7, 32.7 | 29.8 | 27.4, 32.2 |

| Week 4 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 25.5 | 23.0, 28.0 | 29.4 | 26.9, 31.9 | 25.4 | 22.9, 27.9 | 27.8 | 25.2, 30.4 |

| Adjusted | 26.9 | 25.2, 28.7 | 28.2 | 26.4, 30.0 | 25.2 | 23.6, 26.9 | 27.8 | 26.0, 29.5 |

| Week 8 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 24.9 | 22.2, 27.6 | 26.8 | 23.9, 29.7 | 21.2 | 18.6, 23.8 | 24.9 | 22.1, 27.7 |

| Adjusted | 26.5 | 24.2, 28.8 | 25.3 | 23.0, 27.6 | 20.9 | 18.7, 23.0 | 24.8 | 22.6, 27.1 |

| Week 12 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 21.3 | 18.0, 24.6 | 24.7 | 21.8, 27.6 | 15.1 | 12.6, 17.6 | 21.9 | 18.8, 25.0 |

| Adjusted | 22.9 | 20.4, 25.5 | 23.5 | 20.9, 26.0 | 15.0 | 12.6, 17.4 | 21.9 | 19.3, 24.4 |

| Near point of convergence break (cm) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 14.7 | 12.5, 16.9 | 14.4 | 12.4, 16.4 | 13.4 | 11.7, 15.1 | 14.4 | 12.3, 16.5 |

| Week 4 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 10.5 | 8.5, 12.5 | 10.0 | 8.0, 12.0 | 6.9 | 5.4, 8.4 | 12.1 | 10.1, 14.1 |

| Adjusted | 10.2 | 8.6, 11.9 | 10.0 | 8.4, 11.7 | 7.1 | 5.6, 8.7 | 12.0 | 10.4, 13.6 |

| Week 8 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 8.7 | 6.9, 10.5 | 8.4 | 6.8, 10.0 | 5.1 | 4.1, 6.1 | 11.0 | 9.1, 12.9 |

| Adjusted | 8.5 | 7.0, 9.9 | 8.3 | 6.9, 9.7 | 5.4 | 4.1, 6.7 | 10.9 | 9.5, 12.3 |

| Week 12 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 8.0 | 6.1, 9.9 | 6.8 | 5.2, 8.4 | 3.5 | 3.0, 4.0 | 10.3 | 8.4, 12.2 |

| Adjusted | 7.8 | 6.4, 9.2 | 6.8 | 5.4, 8.2 | 4.0 | 2.7, 5.3 | 10.3 | 8.9, 11.7 |

| Positive fusional vergence (Δ) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 11.3 | 10.2, 12.4 | 10.5 | 9.4, 11.6 | 11.0 | 9.9, 12.1 | 11.0 | 10.2, 11.8 |

| Week 4 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 15.4 | 13.5, 17.3 | 19.5 | 17.2, 21.8 | 22.1 | 19.2, 25.0 | 14.9 | 13.0, 16.8 |

| Adjusted | 15.2 | 12.9, 17.6 | 19.7 | 17.3, 22.0 | 22.3 | 20.1, 24.5 | 14.9 | 12.5, 17.2 |

| Week 8 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 17.2 | 15.1, 19.3 | 21.3 | 18.7, 23.9 | 26.9 | 23.7, 30.1 | 17.0 | 14.9, 19.1 |

| Adjusted | 17.0 | 14.5, 19.6 | 21.5 | 19.0, 24.0 | 26.9 | 24.5, 29.2 | 17.0 | 14.5, 19.6 |

| Week 12 | ||||||||

| Unadjusted | 19.1 | 16.8, 21.4 | 22.8 | 19.8, 25.8 | 30.7 | 27.5, 33.9 | 17.8 | 15.5, 20.1 |

| Adjusted | 18.9 | 16.2, 21.6 | 23.0 | 20.3, 25.7 | 30.5 | 28.0, 33.1 | 17.8 | 15.2, 20.5 |

Figure 1.

Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey: Mean at each study visit (A) and Mean change between visits (B).

Table 2.

Results from pair-wise comparisons for each outcome measure at baseline and the 4-, 8-, and 12- week examinations, by treatment group.

| Treatment group |

Baseline to Week 4 | Week 4 to Week 8 | Week 8 to Week 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change | p-value† | Change | p-value† | Change | p-value† | |

| CI Symptom Survey score | ||||||

| HBPP | 2.3 | 0.045 | 0.5 | 0.95 | 3.6 | <0.001 |

| HBCVAT+ | 1.9 | 0.11 | 2.9 | 0.007 | 1.9 | 0.038 |

| OBVAT | 4.5 | <0.001 | 4.4 | <0.001 | 5.8 | <0.001 |

| OBPT | 2.0 | 0.10 | 2.9 | 0.007 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Near point of convergence break (cm) | ||||||

| HBPP | 4.4 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.030 | 0.7 | 0.69 |

| HBCVAT+ | 4.4 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.031 | 1.5 | 0.025 |

| OBVAT | 6.5 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 0.020 | 1.3 | 0.024 |

| OBPT | 2.3 | 0.062 | 1.1 | 0.27 | 0.6 | 0.60 |

| Positive fusional vergence (Δ) | ||||||

| HBPP | 4.1 | 0.004 | 1.9 | 0.37 | 1.9 | 0.26 |

| HBCVAT+ | 8.9 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.37 | 1.5 | 0.46 |

| OBVAT | 11.2 | <0.001 | 4.5 | <0.001 | 3.6 | 0.002 |

| OBPT | 3.9 | 0.005 | 2.2 | 0.19 | 0.8 | 0.87 |

Adjusted for multiple comparisons

Between Group Comparisons: Treatment Groups Compared at 4-, 8-, and 12- week Visits

As seen in Figure 1A, there is slight separation in group means at week 4 that increases at week 8 and increases further at week 12. Overall comparison of the means reveals a significant difference only at weeks 8 (p=0.037) and 12 (p<0.001). Post-hoc comparisons at week 8 show a significant difference between OBVAT and both HBCVAT+ (p=0.037) and HBPP (p=0.004), and a difference which approaches significance between OBVAT and OBPT (p=0.079). No other pair-wise comparisons were significant at week 8 (p-values >0.50). At 12 weeks, the OBVAT group had a significantly lower symptom score compared to the other 3 treatment groups (p-values <0.001), and was the only group with a change of 10 or more points on the CISS (clinically significant change). There were no significant differences between the other 3 groups (p-values >0.50).

Classification of Symptom Level

Table 3 provides the percentage of patients in each group classified as asymptomatic or improved at the 3 post-baseline examinations. At the 4- and 8-week exams, there was no difference in the percentage classified as asymptomatic or improved between treatment groups (p=0.19 at week 4, p=0.39 at week 8). At 12 weeks, the OBVAT group had significantly more patients classified as asymptomatic or improved (73%) as compared to the other 3 treatment groups (47% in HBPP, 38% in HBCVAT+, 43% in OBPT; p-values ≤0.019) and there were no significant differences between the other 3 groups (p-values >0.40).

Table 3.

Classification of signs and symptoms of convergence insufficiency at the 4-, 8-, and 12- week examinations by treatment group.

| Treatment group |

Asymptomatic | Improved CISSa |

Normal NPCb |

Improved NPCc |

Normal PFVd |

Improved PFVe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | ||||||

| HBPP | 8 (15.4%) | 3 (5.8%) | 17 (32.7%) | 12 (23.1%) | 14 (26.9%) | 2 (3.9%) |

| HBCVAT+ | 3 (5.8%) | 4 (7.7%) | 24 (46.2%) | 9 (17.3%) | 24 (46.2%) | 3 (5.8%) |

| OBVAT | 12 (20.3%) | 8 (13.6%) | 34 (57.6%) | 13 (22.0%) | 34 (57.6%) | 4 (6.8%) |

| OBPT | 6 (11.1%) | 7 (13.0%) | 7 (13.0%) | 12 (22.2%) | 18 (33.3%) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Week 8 | ||||||

| HBPP | 10 (18.9%) | 4 (7.6%) | 21 (39.6%) | 16 (30.2%) | 25 (47.2%) | 2 (3.8%) |

| HBCVAT+ | 10 (18.9%) | 8 (15.1%) | 23 (43.4%) | 12 (22.6%) | 26 (49.1%) | 3 (5.7%) |

| OBVAT | 18 (30.0%) | 9 (15.0%) | 41 (68.3%) | 13 (21.7%) | 42 (70.0%) | 2 (3.3%) |

| OBPT | 11 (20.4%) | 10 (18.5%) | 11 (20.4%) | 14 (25.9%) | 19 (35.2%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| Week 12 | ||||||

| HBPP | 18 (34.0%) | 7 (13.2%) | 26 (49.1%) | 15 (28.3%) | 25 (47.2%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| HBCVAT+ | 12 (23.1%) | 8 (15.4%) | 28 (53.9%) | 12 (23.1%) | 27 (51.9%) | 5 (9.6%) |

| OBVAT | 33 (55.9%) | 10 (17.0%) | 51 (86.4%) | 5 (8.5%) | 47 (79.7%) | 2 (3.4%) |

| OBPT | 16 (29.6%) | 7 (13.0%) | 14 (25.9%) | 18 (33.3%) | 23 (42.6%) | 2 (3.7%) |

Defined as a change of 10 or more points from the baseline value

Defined as NPC < 6cm

Defined as a change of 4 or more cm from the baseline value

Defined as PFV > 15 and passes Sheard’s criteria

Defined as a change of ≥ 10Δ from baseline

Near Point of Convergence Break (NPC)

Within Group Comparisons: Change in the NPC Between Exams for each Treatment Group

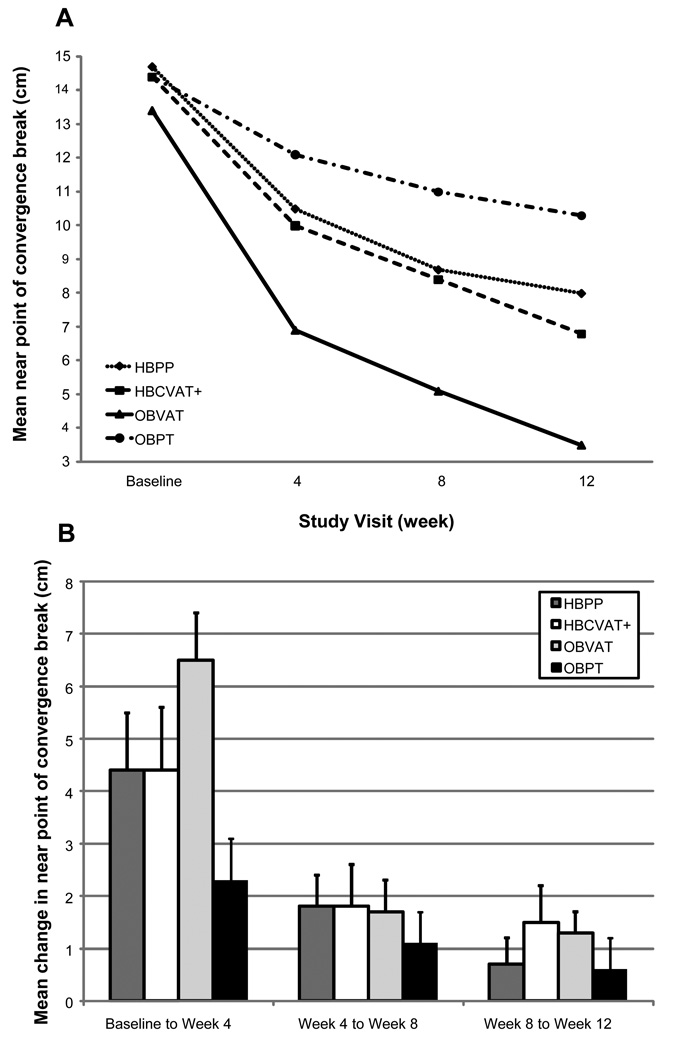

Descriptive statistics for the NPC break at each study visit are displayed in Table 1 and shown graphically in Figure 2A. An improvement in NPC over the 12 weeks of treatment was observed in all groups; however, the rate of improvement differed across groups (p=0.039). As shown in Table 2 and on Figure 2B, all but the OBPT group (p=0.062) showed at least a 4 cm and statistically significant improvement in NPC (p-values<0.001) after 4 weeks of treatment. These gains were larger than the improvement that occurred between any other two visits. Smaller improvements of approximately 2cm were observed in the OBVAT and home-based groups between weeks 4 and 8. Although the NPC continued to improve in the OBVAT and HBCVAT+ groups during the last 4 weeks of treatment, no additional significant improvement was observed in the HBPP group.

Figure 2.

Near point of convergence: Mean at each study visit (A) and Mean change between visits (B).

Between Group Comparisons: Treatment Groups Compared at 4-, 8-, and 12- week Visits

Significant differences between the four treatment groups in mean NPC were observed at week 4 (p<0.001) and were maintained at week 8 weeks and 12 weeks (p<0.0001). Post-hoc comparisons between groups showed that after 4 weeks of treatment, the mean NPC for patients in the OBVAT group was significantly improved compared to the OBPT group (p<0.001); no other significant group differences were observed (p-values >0.05). At week 8, there was a significant difference between the OBVAT group and each of the other treatment groups (p-values≤ 0.024). No other significant differences were observed at week 8 (p-values >0.05). Significant differences between the OBVAT group and each of the other 3 treatment groups were maintained at week 12 (p-values≤0.031). In addition, the mean NPC was significantly improved in the HBCVAT+ group compared to the placebo group (p=0.004) at week 12. No other significant differences were observed (p-values> 0.07).

Classification of NPC Level

The percentage of patients in each group with a normal or improved NPC at weeks 4, 8, and 12 is provided in Table 3. At the week-4 examination, there was a significant difference between the four treatment groups in the percentage classified as normal or improved (p<0.001). Compared to the OBPT group, the percentage of patients with a normal or improved NPC was significantly greater in the OBVAT (p<0.0001), HBCVAT+ (p<0.001) and HBPP (p=0.037) groups. In addition, a greater percentage of patients in the OBVAT group had a normal or improved NPC compared to the HBPP group (p=0.013). At weeks 8 and 12, the percentage of patients in the home-based therapy groups who had a normal or improved NPC remained significantly greater than in the OBPT group (p-values ≤0.033). The proportion of patients in the OBVAT group with a normal or improved NPC (90% at week 8, 95% at week 12) was significantly greater than the other 3 groups (p-values≤0.005) at weeks 8 and 12 and the difference was statistically significant.

Positive Fusional Vergence (PFV)

Within Group Comparisons: Change in the PFV at Near Between Exams for each Treatment Group

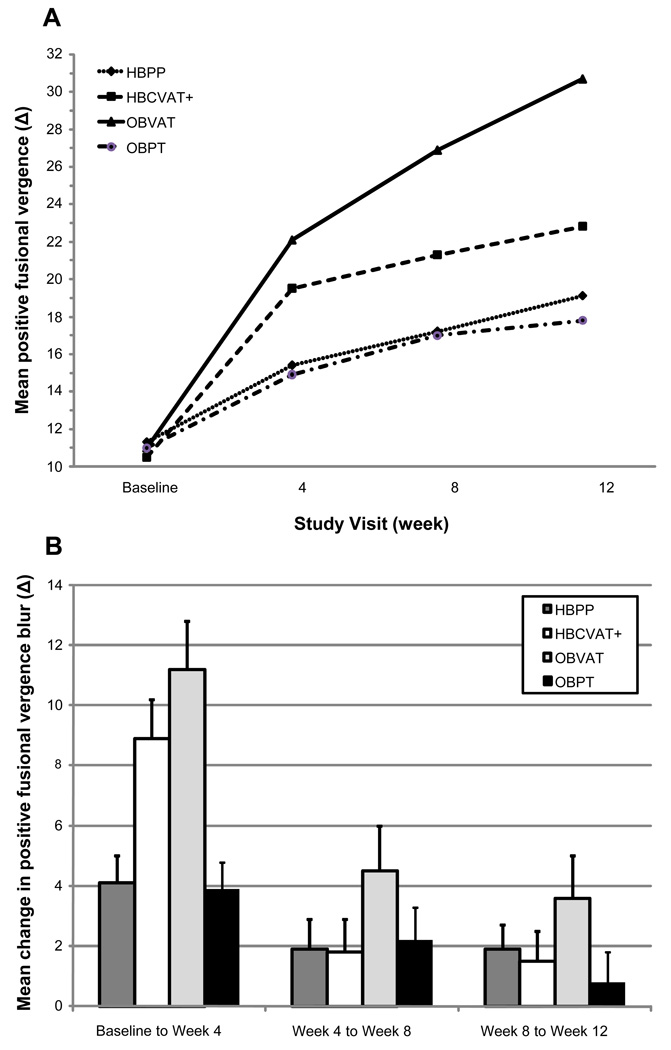

Descriptive statistics for PFV at baseline and each of the 4, 8, and 12-week visits are provided in Table 1 and displayed graphically in Figure 3A. An improvement in PFV was observed in each of the four treatment groups; however, the rate of improvement differed across groups (p<0.001). Similar to NPC, the greatest increases in PFV were observed during the first 4 weeks (see Figure 3B). The mean increase of 11Δ in the OBVAT group and 9Δ in the HBCVAT+ group by week 4 were significant (p-values<0.001) (Table 2). Statistically significant, but smaller improvements of approximately 4Δ, were observed in the HBPP and OBPT groups at week 4 (p-values<0.01). During the next 8 weeks of treatment, significant improvements in PFV were observed only among patients assigned to OBVAT (4 to 8 weeks: mean change =4.5Δ, p<0.001; 8 to 12 weeks: mean change =3.6Δ, p<0.002); no significant improvements were observed in the other 3 groups during this time period (p-values> 0.25).

Figure 3.

Positive fusional vergence break: Mean at each study visit (A) and Mean change between visits (B).

Between Group Comparisons: Treatment Groups Compared at 4-, 8-, and 12- Week Visits

As seen in Figure 3A, there is a significant difference between groups as early as week 4 (p<0.0001) as the mean PFV for patients in the OBVAT and HBCVAT+ groups begins to diverge from the other 2 groups. At week 4, the mean PFV in the OBVAT group was significantly greater than that in either the HBPP (p<0.001) or OBPT (p<0.001) groups. In addition, the difference in mean PFV was significantly different between the HBCVAT+ and the OBPT groups (p=0.026) and approached significance between the HBCVAT+ and the HBPP groups (p=0.056). By week 8, the mean PFV in the OBVAT group was significantly greater than that in any of the other 3 treatment groups (p-values ≤0.017); however, there was no longer a significant difference between the HBCVAT+ and the OBPT groups (p=0.089). At week 12, there remained a significant difference between the OBVAT group and each of the other 3 treatment groups (p-values<0.001). There was also a significant difference between the HBCVAT+ and the OBPT groups (p=0.047).

Classification of PFV Level as Normal or Improved

As seen in Table 3, at the week 4, 8 and 12 exams, there was a significant difference in the percentage of those with a normal or improved PFV in each treatment group (p-values≤0.018). At week 4, the OBVAT group had a significantly higher percentage with normal or improved PFV (64%) than that in either the HBPP (31%; p=0.002) or OBPT (35%; p=0.007) groups. No significant difference was observed between the OBVAT and HBCVAT+ groups at week 4 (p=0.41). After 8 weeks of treatment, the percentage of patients with normal or improved PFV in the OBVAT group (73%) remained significantly greater than that in the HBPP (51%; p=0.043) and the OBPT (39%; p<0.001) treatment groups. The difference between the OBVAT and HBCVAT+ groups in the percentage with normal or improved PFV at week 8 approaches significance (p=0.076). At week 12, the percentage of patients with normal or improved PFV in the OBVAT group (83%) was significantly greater than that in any of the other treatment groups (62% in HBCVAT+, 57% in HBPP, 46% in OBPT; p-values≤0.008), and there were no significant differences between the other 3 groups (p-values≥0.20).

Composite Measure of Using CISS, NPC, and PFV

The percentage of patients classified as successful or improved using the composite measure of symptoms, NPC, and PFV is shown in Table 4. No differences were observed between treatment groups at weeks 4 (p=0.18) or 8 (p=0.10). However, by week 12, the percentage of patients classified as successful or improved was significantly greater in the OBVAT group (73%) than in the other three groups (43% in HBPP, 33% in HBCVAT+, and 35% in OBPT; p-values≤0.002). No other differences were observed at week 12 (p-values≥0.50)

Table 4.

Improvement in composite measures of convergence insufficiency at the 4-, 8-, and 12- week examinations by treatment group.

| Treatment group |

Normal or Improveda NPC & PFV |

Composite measure of CISS, NPC & PFV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successfulb | Successful or Improvedc |

||

| Week 4 | |||

| HBPP | 11 (21.2%) | 2 (3.8%) | 5 (9.6%) |

| HBCVAT+ | 22 (42.3%) | 1 (1.9%) | 5 (9.6%) |

| OBVAT | 37 (62.7%) | 5 (8.5%) | 15 (25.4%) |

| OBPT | 7 (13.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 7 (13.0%) |

| Week 8 | |||

| HBPP | 20 (37.7%) | 3 (5.7%) | 144 (26.4%) |

| HBCVAT+ | 24 (45.3%) | 4 (7.6%) | 1 (26.4%) |

| OBVAT | 42 (70.0%) | 12 (20.0%) | 26 (43.3%) |

| OBPT | 10 (18.5%) | 3 (5.6%) | 14 (25.9%) |

| Week 12 | |||

| HBPP | 29 (54.7%) | 8 (15.1%) | 23 (43.4%) |

| HBCVAT+ | 29 (55.8%) | 5 (9.6%) | 17 (32.7%) |

| OBVAT | 47 (79.7%) | 24 (40.7%) | 43 (72.9%) |

| OBPT | 18 (33.3%) | 5 (9.3%) | 19 (35.2%) |

Defined as NPC < 6cm OR an improvement of ≥ 4 cm as well as a PFV > 15Δ and passes Sheard’s criteria OR a change of ≥ 10Δ

Defined as CISS < 16, NPC < 6, and normal PFV

Defined as CISS < 16 or change ≥ 10 and at least one of the following: NPC < 6cm, change in NPC ≥ 4cm, normal PFV, or change in PFV ≥ 10Δ.

Composite Measure Using NPC and PFV

As seen in Table 4, at weeks 4, 8 and 12, there was a significant difference between groups in the percentage classified as successful or improved (p-values<0.0001). At week 4, significantly more children in the OBVAT group were successful or improved (63%) than in the HBPP (21%, p<0.0001), the HBCVAT+ (42%, p=0.032), and the OBPT (13%, p<0.0001) groups. In addition, a significantly higher proportion of children in the HBCVAT+ group were successful or improved compared with both the HBPP (p=0.021) and the OBPT (p<0.001) groups. After 8 weeks of treatment, the percentage of those normal or improved in the OBVAT group (70%) was significantly greater than that in any of the other groups (38% in HBPP, 45% in HBCVAT+, and 19% in OBPT; p-values≤0.008). The percentage of normal or improved in the HBPP and the HBCVAT+ groups was significantly greater than that in the OBPT group (p-values≤0.027). At week 12, the percentage of those normal or improved in the OBVAT group (80%) remained significantly greater than that in any of the other groups (55% in HBPP, 56% in HBCVAT+, 33% in OBPT; p-values≤0.005). In addition there remained a significant difference between the OBPT and the two home based groups (p-values≤0.026).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the kinetics of change in symptoms and clinical signs for four different 12-week therapy regimens for 9 to 17-year-old children with symptomatic CI who were enrolled into the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial. Treatment group differences were observed as early as week 4. OBVAT resulted in a more rapid improvement in symptoms and clinical measures of NPC and PFV than HBPP, HBCVAT+, and OBPT. The OBVAT group had the greatest decrease in symptoms at each visit and was the only group that demonstrated a significant improvement in symptoms, NPC, and PFV at each of three follow-up examinations. The data presented herein demonstrate that the superiority of OBVAT at the 12 week outcome visit as reported previously1 becomes evident by 4 weeks of treatment. We reported similar results in a smaller, randomized clinical trial.6

Symptoms as measured by the CISS improved more slowly than clinical signs (NPC and PFV). Although our data show statistically significant changes in NPC and PFV even after the first 4 weeks, it appears that patients began reporting relief of symptoms only when the magnitude of change for NPC and PFV reached sufficient levels. The majority of patients in all groups were still symptomatic at the 4 and 8 week visits. It was not until week 12 that 73% of the patients in the OBVAT group were asymptomatic or improved. In the other 3 groups, the majority of patients continued to be symptomatic even at 12 weeks. This outcome tends to support Sheard’s 3 well-known postulate that there is a correlation between symptoms and the PFV and phoria relationship. We previously reported that NPC and PFV are predictive of symptoms following treatment for CI.11 The data from this paper further define this relationship.

The largest improvements for both NPC and PFV occurred within the first 4 weeks of treatment. Only patients in the OBVAT and HBCVAT+ groups continued to experience significant improvements in the NPC between weeks 8 and 12 and only patients in the OBVAT group continued to achieve significant gains in PFV at weeks 8 and 12. It is interesting that the changes in PFV in the HBPP group was no different from the small changes that occurred in the OBPT group. One explanation for this lack of change in PFV could be that treatment adherence may have declined after week 4. However, we did not find a significant change in patient reported or therapist estimated adherence from week 4 to week 12 in any of the groups.1 The decline in the rate of change in clinical signs also does not appear to be the result of a ceiling effect because at 8 weeks the percentage of patients with normal NPC or PFV was less than 50% in the home-based groups.

The small improvement in PFV that occurred in the HBPP group as compared to the OBVAT group may be related to differences in the underlying therapeutic effect of the active therapies. One of the key differences among various active treatment approaches for CI is the ability to control and manipulate vergence and accommodative demand. To increase fusional vergence amplitudes a therapy technique must either maintain accommodation at the plane of regard and change the stimulus to the vergence system, or maintain vergence at the plane of regard and change the stimulus to accommodation.12 HBPP does not accomplish either of these two objectives. Rather, during HBPP the patient tries to maintain single vision as the target is moved toward the eyes and is able to continue to accommodate at the plane of the pencil. Therefore, accommodative/convergence can be used (rather than fusional vergence) to achieve the goal of maintaining single, binocular vision and the main therapeutic effect is to improve overall convergence, rather than fusional vergence. It is, therefore, not surprising that while NPC improves during the first 8 weeks, there are minimal additional changes in PFV. In contrast, OBVAT allows the therapist to freely manipulate vergence and accommodative demand using multiple procedures. It includes procedures that are specifically designed to target fusional vergence and others that specifically improve overall convergence. HBCAVT+ is also designed to allow manipulation of vergence and accommodative demand should theoretically yield similar results as OBVAT. The results from this clinical trial, however, demonstrated that after initial increases in PFV at near during the first 4 weeks, there are limited changes from week 4 to week 12 with HBCAVT+. Perhaps the greater variety of procedures available in OBVAT is important or the therapists’ ability to observe the patient’s performance, provide feedback to the patient, and help the patient overcome obstacles are important factors not available during HBCVAT+. It is also possible that the results for HBCVAT+ would have been better with changes in the study design. In the CITT study design, patients in HBCVAT+ group were not required to complete the entire program before the outcome examination. In addition, patient performance was not monitored using the program’s internet tracking option. In future studies closer monitoring of adherence, and required completion of the computer’s auto-mode may improve the outcome for this treatment.

The data reported herein about treatment kinetics in the CITT help provide guidance for clinicians about the timing of follow-up visits and suggested length of therapy. Because the largest changes in both NPC and PFV occur by 4 weeks for both OBVAT and both home-based treatments, 4 weeks appears to be an appropriate time for a progress evaluation. Absence of any improvements at a 4-week follow-up examination would be cause for concern and lead the clinician to questions of adherence to home therapy or the accuracy of the diagnosis of CI.

The length of therapy required to achieve optimum results is not known. While clinical guidelines13 suggest the length of treatment for office-based therapy is generally 12–24 weeks, these are primarily based on expert opinion. For home-based treatments such as HBPP or HBCVAT+, there are no guidelines available. The CITT was not designed to determine the maximum effectiveness of treatments for CI. The shortest recommended duration of treatment (12 weeks) according to clinical guidelines 13 was chosen because of concerns regarding parents’ willingness to have their symptomatic children receive placebo therapy for more than 12 weeks. In regard to the recommended length of therapy, we are unable to use the CITT results to establish the optimal number of sessions or weeks to achieve maximal treatment effectiveness. However, the data show that at least 12 weeks of treatment are required. The percentage of patients classified as “successful” or “improved” increased in all groups from week 4 through week 12. Even for the most effective treatment (OBVAT), the proportion of patients classified as successful or improved would have been significantly poorer if we had stopped at either 4 weeks (34%) or 8 weeks (45%), instead of 12 weeks (73%). One of the unanswered questions is whether the success rates for OBVAT or home-based therapy would have improved if therapy was continued beyond 12 weeks. There are suggestions from our data that this may be the case and that additional visits may have resulted in a better result for both office and home-based treatments. The answer to this question will have to await further research.

In translating the results of these data into clinical practice, our data suggest that lack of improvement in clinical findings after 4 weeks should lead to questions of accurate diagnosis and treatment adherence. At 8 weeks both the NPC and PFV should be at or near clinically normal levels for the majority of patients (about 70%) undergoing OBVAT and for less than half of patients undergoing HBPP or HBCVAT+. Relief of symptoms, however, requires more treatment and generally does not approach normal levels until the child has undergone 12 weeks of treatment. The fact that the clinical findings are likely to improve during the early phases of treatment before the patient begins experiencing relief of symptoms should be discussed during the initial consultation with patient and parents. Although our study evaluated a 12-week treatment protocol, it is certainly reasonable to conclude that if a patient is still symptomatic at 12 weeks, it may be appropriate to continue treatment for another 4 weeks or until the patient’s symptoms are relieved or until continued progress is no longer seen. Finally, because clinical signs improve before symptoms, treatment should not be stopped solely on the basis of NPC and/or PFV improvement.

The strengths of our study include its prospective design, adequate sample size, randomization of subjects to avoid treatment assignment bias and to control for known and unknown confounders, a placebo control group for the OBVAT group, evidence of successful masking of examiners and patients in the OBVAT and OBPT groups,14 and outstanding follow-up.1 It was not possible to mask the HBCVAT+ and PPT groups to their treatment because of the self-performed nature of the treatment. Although slight differences in estimated adherence to therapy among the groups were identified, accounting for these differences did not affect the results of treatment group comparisons for the CISS, NPC, or PFV.1

CONCLUSIONS

In 9 to 17-year-old children with symptomatic CI receiving 12 weeks of OBVAT, HBPP, HBCVAT+, or OBPT the rate of improvement is more rapid for the clinical signs (NPC and PFV) than for the symptoms of CI. OBVAT results in a more rapid improvement in symptoms and clinical measures, as well as a greater percentage of patients classified as successful or improved when compared with HBPP, HBCVAT+, or OBPT. Less than 12 weeks of treatment would lead to significantly lower overall treatment effectiveness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported through a cooperative agreement from the National Eye Institute

The Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Study Group

Clinical Sites

Sites are listed in order of the number of patients enrolled in the study with the number of patients enrolled is listed in parentheses preceded by the site name and location. Personnel are listed as (PI) for principal investigator, (SC) for coordinator, (E) for examiner, and (VT) for therapist.

Study Center: Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (35)

Susanna Tamkins, OD (PI); Hilda Capo, MD (E); Mark Dunbar, OD (E); Craig McKeown, MD (CO-PI); Arlanna Moshfeghi, MD (E); Kathryn Nelson, OD (E); Vicky Fischer, OD (VT); Adam Perlman, OD (VT); Ronda Singh, OD (VT); Eva Olivares (SC); Ana Rosa (SC); Nidia Rosado (SC); Elias Silverman (SC)

Study Center: SUNY College of Optometry (28)

Jeffrey Cooper, MS, OD (PI); Audra Steiner, OD (E, Co-PI); Marta Brunelli (VT); Stacy Friedman, OD (VT); Steven Ritter, OD (E); Lily Zhu, OD (E); Lyndon Wong, OD (E); Ida Chung, OD (E); Kaity Colon (SC)

Study Center: UAB School of Optometry (28)

Kristine Hopkins, OD (PI); Marcela Frazier, OD (E); Janene Sims, OD (E); Marsha Swanson, OD (E); Katherine Weise, OD (E); Adrienne Broadfoot, MS, OTR/L (VT, SC); Michelle Anderson, OD (VT); Catherine Baldwin (SC)

Study Center: NOVA Southeastern University (27)

Rachel Coulter, OD (PI); Deborah Amster, OD (E); Gregory Fecho, OD (E); Tanya Mahaphon, OD (E); Jacqueline Rodena, OD (E); Mary Bartuccio, OD (VT); Yin Tea, OD (VT); Annette Bade, OD (SC)

Study Center: Pennsylvania College of Optometry (25)

Michael Gallaway, OD (PI); Brandy Scombordi, OD (E); Mark Boas, OD (VT); Tomohiko Yamada, OD (VT); Ryan Langan (SC), Ruth Shoge, OD (E); Lily Zhu, OD (E)

Study Center - The Ohio State University College of Optometry (24)

Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (PI); Michelle Buckland, OD (E); Michael Earley, OD, PhD (E); Gina Gabriel, OD, MS (E); Aaron Zimmerman, OD (E); Kathleen Reuter, OD (VT); Andrew Toole, OD, MS (VT); Molly Biddle, MEd (SC); Nancy Stevens, MS, RD, LD (SC)

Study Center: Southern California College of Optometry (23)

Susan Cotter, OD, MS (PI); Eric Borsting, OD, MS (E); Michael Rouse, OD, MS, (E); Carmen Barnhardt, OD, MS (VT); Raymond Chu, OD (VT); Susan Parker (SC); Rebecca Bridgeford (SC); Jamie Morris (SC); Javier Villalobos (SC)

Study Center: University of CA San Diego: Ratner Children's Eye Center (17)

David Granet, MD (PI); Lara Hustana, OD (E); Shira Robbins, MD (E); Erica Castro (VT); Cintia Gomi, MD (SC)

Study Center: Mayo Clinic (14)

Brian G. Mohney, MD (PI); Jonathan Holmes, MD (E); Melissa Rice, OD (VT); Virginia Karlsson, BS, CO (VT); Becky Nielsen (SC); Jan Sease, COMT/BS (SC); Tracee Shevlin (SC)

CITT Study Chair

Mitchell Scheiman, OD (Study Chair); Karen Pollack (Study Coordinator); Susan Cotter, OD, MS (Vice Chair); Richard Hertle, MD (Vice Chair); Michael Rouse, OD, MS (Consultant)

CITT Data Coordinating Center

Gladys Lynn Mitchell, MAS, (PI); Tracy Kitts, (Project Coordinator); Melanie Bacher (Programmer); Linda Barrett (Data Entry); Loraine Sinnott, PhD (Biostatistician); Kelly Watson (Student worker); Pam Wessel (Office Associate)

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD

Maryann Redford, DDS., MPH

CITT Executive Committee

Mitchell Scheiman, OD; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD, MS; Richard Hertle, MD; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS; Maryann Redford, DDS., MPH; Michael Rouse, OD, MSEd

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

Marie Diener-West, PhD, Chair, Rev. Andrew Costello, CSsR, William V. Good, MD, Ron D. Hays, PhD, Argye Hillis, PhD (Through March 2006), Ruth Manny, OD, PhD

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00338611.

REFERENCES

- 1.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. Randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1336–1349. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. The convergence insufficiency treatment trial: design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:24–36. doi: 10.1080/09286580701772037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheard C. Zones of ocular comfort. Am J Optom. 1930;7:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Cotter SA, Kulp M, Scheiman M, Barnhardt C, Bade A, Yamada T. Validity of the convergence insufficiency symptom survey: a confirmatory study. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:357–363. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181989252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borsting EJ, Rouse MW, Mitchell GL, Scheiman M, Cotter SA, Cooper J, Kulp MT, London R. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in children aged 9 to 18 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:832–838. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, Cooper J, Kulp M, Rouse M, Borsting E, London R, Wensveen J. A randomized clinical trial of treatments for convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:14–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulp M, Mitchell GL, Borsting E, Scheiman M, Cotter S, Rouse M, Tamkins S, Mohney BG, Toole A, Reuter K. Effectiveness of placebo therapy for maintaining masking in a clinical trial of vergence/accommodative therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2560–2566. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borsting E, Rouse MW, De Land PN The Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) Group. Prospective comparison of convergence insufficiency and normal binocular children on CIRS symptom surveys. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:221–228. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199904000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidak Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Statist Assoc. 62:626–633. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toole AJ, Mitchell GL, Taylor Kulp M, Earley MJ CITT Study Group. Relationship between clinical measures and symptoms following treatment for convergence insufficiency in the CITT Study. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;85 E-Abstract 070006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheiman M, Wick B. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative and Eye Movement Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper JS, Burns CR, Cotter SA, Daum KM, Griffin JR, Scheiman MM. American Optometric Association Clinical Practice Guideline: Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction. St. Louis: American Optometric Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulp M, Mitchell GL, Borsting E, Scheiman M, Cotter S, Rouse M, Tamkins S, Mohney BG, Toole A, Reuter K. Effectiveness of placebo therapy for maintaining masking in a clinical trial of vergence/accommodative therapy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2560–2566. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]