Abstract

We examined the association between context of entry into the United States and symptoms of depression in an older age Mexican-origin population. We found that context of entry was associated with the number of depressive symptoms reported in this population. Specifically, immigrants who arrived to the U.S. following the Mexican Revolution (1918–1928) reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms, and those who arrived following enactment of the Immigration Reform Control Act (1965–1994) reported significantly more symptoms of depression, compared to those who arrived in the Bracero era (1942–1964). These findings suggest that sociopolitical context at the time of immigration may be associated with long-term psychological well-being. They contribute to a growing body of literature that suggests that the context of immigration may have long-term implications for the health of immigrant populations. We discuss implications of our findings for understanding relationships between immigration policies and the health of Mexican immigrant populations.

Keywords: Latino, Sociopolitical context, Context of entry, Depressive symptoms

Introduction

Investigations of acculturation and health outcomes have faced challenges in connecting findings to sociopolitical context—that is, the social, economic, political and historical circumstances that shape an individual’s lived experiences. The ability to link patterns of health and illness to the broader contexts within which they emerge can help our understanding of associations between social policies and population health. Understanding how experiences vary can elucidate factors that influence the health of contemporary Latinos. In this study, we seek to contribute to this end through an examination of associations between sociopolitical context at the time of entry into the United States and depressive symptoms in an older Mexican-origin population.

Depressive symptoms are reportedly associated with higher mortality rates among older Mexican Americans with chronic medical conditions [1–5]. Given the projected five-fold growth of the older Latino population by 2050 [6], it is important to understand factors associated with depressive symptoms in this population. Examining context can contribute new insights and further our understanding of heterogeneity in Latino health outcomes.

Latino immigrants arrive in the U.S. from multiple Latin American countries with varying political climates and geographically distinct migratory settlement patterns [7]. This diversity reflects multiple contexts of exit—the circumstances of emigrants’ country of origin when they departed [8]—and contributes to the need for a critical population-specific evaluation of Latino health studies. Further complexities arise in considering each country’s relationship with the U.S., the specific historical climate at time of entry into the U.S. as that varies over time, and the independent and cumulative implications of contexts of exit and entry for health. To begin to investigate associations between context and the health of immigrants, this study focuses on one aspect of this problem: variations in symptoms of depression among individuals from a single country of origin, Mexico, across contexts of entry to the U.S.

U.S.-Mexican history is complex and reflected in distinct historical periods or eras [7]. The circumstances that immigrants encounter upon arrival into the U.S. influence social and economic opportunities and challenges. Social conditions encountered by Mexicans who immigrate to the U.S. have varied dramatically over time, leading to questions about the extent to which they may be associated with differential health patterns.

Sociopolitical Contexts Relevant to Mexican-Origin Populations

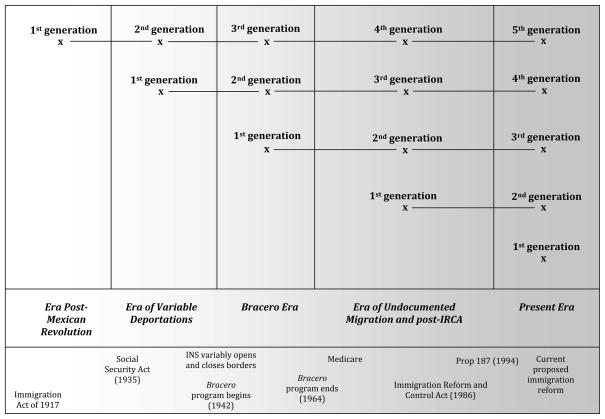

Durand and colleagues have described major shifts in social, economic, and/or historical contexts since the beginning of the 20th century experienced by Mexican-origin populations in the U.S. [9]. Drawing upon their work, we briefly describe four eras relevant to current U.S. Mexican-origin immigrants, below (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A heuristic diagram illustrating US-Mexican experiences across sociopolitical contexts

Post-Mexican Revolution Era (1918–1928)

After the Mexican Revolution, the Mexican economy worsened and Mexico saw a large-scale emigration of agricultural, artisanal, and industrial laborers to the U.S. due to violence and political turmoil [10]. While the context of exit for this population was characterized by political disruption, the context of entry into the U.S. was characterized by lenient immigration policies [11].

Era of Variable Deportations (1929–1941)

The relatively neutral social climate following the Mexican revolution lasted only until the Great Depression, when domestic labor concerns led to the enforcement of existing U.S. immigration policies for Mexican-origin populations. As many as 415,000 Mexicans were deported from 1929 through the mid-1930s while immigration policies were variably enforced [11, 12]. This uneasy social climate for Mexican-origin populations continued until labor shortages triggered by World War II led the U.S. to initiate the Bracero guest worker program.

The Bracero Era (1942–1964)

The Bracero Program, introduced in 1942, authorized Mexican immigrants to fill labor shortages on farms and railroad expansion projects [11–13]. The Bracero Program continued until 1964, when the historical climate in the U.S. reverted to one similar to that of Era of Variable Deportations, and negative sentiments toward undocumented immigrants became more prevalent [11–13].

Post-Immigration Reform and Control Act Era (IRCA; 1965–1994)

Under growing pressure from organized labor and unwarranted fears that communist spies were entering the U.S. illegally from Mexico, the U.S. began deportation efforts that pejoratively became known as “Operation Wetback” [11, 13]. As many as one million undocumented Mexican immigrants were deported, as were many Mexican-origin U.S. citizens whose deportation represented a clear violation of civil rights [11]. Simultaneously, the IRCA granted amnesty and U.S. citizenship to many Mexican immigrants who had remained in the U.S. illegally after the end of the Bracero Program. Thus, social policies simultaneously created a sentiment of fear and presented opportunities for citizenship among Mexican-origin populations.

Context of Entry and the Health of Mexican Immigrants

Embedded in these variable U.S. immigration policies are potential insults as well as opportunities with short- and long-term implications for the psychological well-being of Mexican-origin populations. Policies at times offered economic opportunities with implications for health, while others also prevented individuals from crossing the U.S.-Mexico border legally for extended periods of time, leading to fear of deportations and punitive treatment. Over time, the implications of these policies for population-level health have become clearer [12, 14–17]. In addition to trauma from disruptions in family and social networks, fears of deportation and punitive treatment have direct implications for mental health. Trauma and loss increase the risk for changes in socioeconomic position and mental disorders have potential lifecourse implications for health, especially without access to healthcare [18–21].

Conceptual Framework

Cabassa described a framework of contextual factors influencing acculturation based on pioneering work in acculturation theory, and considers the contexts of immigration with societal and individual-level factors affecting an individual at those times [22]. Building on this effort to shift analyses toward an understanding of the contexts that may influence processes of migration and their implications, we examine the sociopolitical contexts of entry encountered by Mexican immigrants to the U.S. over the past century, and their implications for mental health.

Commonly used proxies for acculturation (e.g., nativity, years in the U.S.) are often conceptualized as individual-level characteristics that may interact with social or physical contexts. Our framework illustrates how context shapes both social structure and individual access to opportunity and, therefore, health outcomes. For example, given established relationships between education and symptoms of depression [23, 24], Mexican immigrants who experience barriers to higher education would be expected to experience a greater number of depressive symptoms compared to those whose context of entry was more conducive to educational opportunities.

U.S.-Mexican Experiences Across Sociopolitical Contexts

Figure 1 illustrates how domains of U.S.-Mexican experience (e.g., generational status) may cross-cut historical eras. For example, a first generation Mexican immigrant may enter the U.S. in an era that welcomes, or at least encourages, them into particular labor force niches (e.g., Bracero era). Alternatively, they may enter into an environment conducive to depression fraught with unpredictable hostility and harassment (e.g., IRCA era) [25]. We expect that these circumstances will have different implications for psychological well-being. Because individuals enter the U.S. in different eras, prior findings that attribute differences in mental health outcomes to, for example, nativity, may be confounded by these contextual differences. In this study, we sought to specifically examine associations between sociopolitical context and depressive symptoms among Mexican immigrants to the U.S.

Methods

Sample

We examined the immigrant subsample of the baseline wave (1993–1994) of the Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (H-EPESE, n =1,346), a prospective, stratified, population-based cohort study of community-dwelling Mexican-origin individuals in the Southwestern U.S. aged 65 years and older. Data were accessed through the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Ann Arbor, MI [26].

Measures

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) was the primary outcome measure of depressive symptoms (range 0–60) [27]. This measure has been validated for use with Mexican-origin populations [28]. We normalized CES-D scores using the natural log of the summary score and multiplied the coefficient by 100, yielding the percent change for a one-unit increase in each predictor variable, holding all other covariates in the model constant [29].

Predictor variables included era of arrival to the U.S., education and annual household income. Sociopolitical context is operationalized as the era during which immigrants came to the U.S. to stay (Fig. 1). Eras were one of four sociopolitical contexts [9], as described above, assigned on the basis of the time each respondent came to the U.S. Eras were defined as dummy variables as follows: Post Mexican Revolution included individuals immigrating between 1918 and 1928; Era of Variable Deportations, encompassing those who arrived between 1929 and 1941; Bracero era, including individuals who entered the U.S. between 1942 and 1964; and the Post-IRCA era captured individuals immigrating between 1965 and 1994. Because we hypothesized the Bracero era was the most positive context of entry conducive to better psychological well-being, this era became the referent group for testing the association between era and depressive symptoms. Education was measured as self-reported highest level of education achieved and was treated as a continuous measure, as was annual household income, measured categorically ranging from $0 to $4,999 to $50,000 and over. Because age, gender [30, 31] and marital status [32, 33] have been associated with depressive symptoms, and in order to examine independent effects of sociopolitical context above and beyond these demographic variables, they were added as dichotomous covariates in the analyses. Age in years was a continuous measure, and gender and marital status were both dichotomous (female and married were referent groups).

Analysis

We used Stata version 10.1 for Windows (College Station, TX) to compute generalized least-squares estimates of depressive symptoms with population-level weights in each era-based model, controlling for era. Age, gender, and marital status were included as covariates in the models since they are independently associated with depressive symptoms.

We first tested the hypothesis that sociopolitical context is associated with systematic differences in depressive symptoms, above and beyond the effects of the sociodemographic covariates (model 1) within this subsample of Mexican immigrants. We then examined models that incorporated education and household income to assess the extent to which these variables attenuated associations between sociopolitical context and depressive symptoms, controlling for age, gender and marital status (model 2).

Results

Estimates for the study variables in the immigrant subsample are shown in Table 1. Overall, the mean CES-D summary score for the first generation immigrants in this older sample was 13.3 (range =1–51), and the mean age was 73.9 years (range =65–99; mean ages were 74.3 for men and 73.6 for women). The greatest proportion of the sample immigrated during the Bracero era (44%), followed by the Post-IRCA era (31%).

Table 1.

Weighted descriptive statistics for study variables, Hispanic established populations for the epidemiologic studies of the elderly, immigrant subsample, 1993–1994

| n | Percent | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D summary score | 1,051 | – | 13.3 | 9.60 |

| Natural log of CES-D summary score | 1,051 | – | 2.2 | 0.9 |

| Sociopolitical context | ||||

| Post-Mexican revolution era | 167 | 14.0 | – | – |

| Era of variable deportations | 132 | 14.0 | – | – |

| Bracero era | 530 | 44.3 | – | – |

| Post-IRCA era | 367 | 30.7 | – | – |

| Age | 1,346 | – | 73.9 | 7.4 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 580 | 43.1 | – | – |

| Female | 766 | 57.0 | – | – |

| Socioeconomic position | ||||

| Highest year of school completed | 1,173 | – | 4th grade | 1.3 |

| Yearly household income (US dollars in thousands) | 1,160 | – | $5–$9,999 | 3.3 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 715 | 53.1 | – | – |

| Not married | 631 | 46.9 | – | – |

Results from multivariate analyses (Table 2) show modest support for our hypothesis that sociopolitical context was associated with differences in depressive symptoms, above and beyond the effects of age, gender and marital status. Specifically, individuals arriving to the U.S. in the Post-Mexican Revolution era (1918–1928) reported significantly lower depressive symptoms compared to immigrants arriving to the U.S. in the Bracero era (1942–1964). Those arriving in the Post-IRCA era (1965–1994) reported a significantly higher number of depressive symptoms compared to immigrants arriving during the Bracero era (model 1). The explained variance (adjusted R2) for model 1 was 5%.

Table 2.

Depressive symptoms regressed on sociopolitical context and education, controlling for age, gender and marital status, Hispanic established populations for the epidemiologic studies of the elderly, immigrant subsample, 1993–1994

| Model 1 (n =1,051) |

Model 2 (n =1,036) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | |

| Intercept | 1.630*** | 0.336 | 1.906*** | 0.347 |

| Age | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Female | 0.339*** | 0.063 | 0.341*** | 0.064 |

| Married | −0.077 | 0.063 | −0.065 | 0.063 |

| Post-Mexican revolution eraa | −0.221* | 0.092 | −0.198* | 0.093 |

| Era of variable deportationsa | 0.191 | 0.102 | 0.227* | 0.103 |

| Post-IRCA eraa | 0.166* | 0.065 | 0.149* | 0.066 |

| Education | – | – | −0.021* | 0.009 |

| Household income | – | – | – | – |

| R2 | 0.059 | 0.063 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||

P < 0.05;

P < 0.001

Referent group is Bracero Era

Results shown for model 2 indicate that education was an independent predictor of depressive symptoms. With the addition of education in the model, the coefficient for the Era of Variable Deportations becomes statistically significant, suggesting the greater numbers symptoms of depression among those who entered the U.S. during the Era of Variable Deportations compared to those who entered in the Bracero era are not apparent until education is accounted for. The amount of variance (adjusted R2) explained by the model increased to 6%. We also examined these associations controlling for household income but found no significant effects (results not shown). Furthermore, we found that women reported higher levels of symptoms of depression than men, even after accounting for the effects of education, income and era, which is consistent with the literature [30–33].

Discussion

We found that Mexican immigrants to the U.S. arriving in the Era of Variable Deportations (1929–1941) and the Post-IRCA era (1965–1994), periods when discrimination and disruptions due to deportations were at historical peaks, reported significantly higher depressive symptoms compared to immigrants arriving during the Bracero era (1942–1964), an era that encouraged Mexican immigrants to come to the U.S. for politically supported (although restricted) economic opportunities. The results presented here support the hypothesis that differences in depressive symptoms may be partially explained by context of entry. Policies in place at the time of immigration may affect mental health with subsequent implications for physical health over the lifecourse [17–19, 22].

Immigration Context of Entry as a Complementary Process

We found modest evidence in support of our hypothesis that context of entry was associated with depressive symptoms, although these effects were not consistently in the directions hypothesized. The discovery of a difference in number of depressive symptoms by era provides some support for our hypotheses that a supportive social context at U.S. entry may have enduring positive implications for psychological well-being. That is, Bracero era immigrants encountering fewer barriers to immigration with some opportunities for employment, reported fewer depression symptoms later in life than Era of Variable Deportation or post IRCA era immigrants who encountered pervasive hostility and threats of deportation. This suggests that immigration policies that contribute to anti-immigrant sentiment and disruptions may have long-term negative implications for psychological well-being.

Thus, our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that context of entry may be associated with indicators of mental health in later life. In contrast however, those who entered the U.S. to stay immediately following the Mexican Revolution reported fewer symptoms of depression compared to those who entered in the Bracero era. This finding suggests that this “context of entry” into the U.S. should be considered as complementary to what Portes and colleagues have described as “context of exit” for migration [8]. There may be positive health implications for populations migrating because of political turmoil, such as during and immediately following the Mexican Revolution [34, 35], and examining the post-Mexican Revolution era as a positive context of entry captures one aspect of a multi-faceted process.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first we are aware of that directly examines health implications of sociopolitical contexts of entry as a potential underlying mechanism for traditionally examined covariates of health within a Latino population. By placing measures that have been previously used as proxies of acculturation within the context of historical eras in a heuristic diagram (Fig. 1), and demonstrating significant associations between sociopolitical context and depressive symptoms, this study suggests that the inclusion of context may strengthen efforts to explain variations in Mexican immigrant health outcomes.

However, our results, and therefore generalizations of our study findings, have limitations, including the cross-sectional nature of the study; the use of an approximate measure of sociopolitical context; the use of highest level of education and household income as measures used to control for socioeconomic position; the exclusion of current health conditions as a covariate in analyses; the focus on contexts of entry without contexts of exit; the individual-level analysis conducted; missing data; and the linear modeling of the analysis. Moreover, because the study used the baseline measures from a longitudinal study, future analyses can investigate how our conclusions change across time. That we found a significant association between era and number of depressive symptoms in an older age population suggests that the association between sociopolitical context and health may be robust enough to examine in conjunction with acculturation scales and in younger populations, where the inclusion of additional variables may allow more variance to be explained.

This study is also limited by the individual-level analysis and linear modeling applied to address research questions. Prior studies suggested research on Latino populations would benefit from studies that divert away from an individual-level focused measure of acculturation to more structural conditions [36]. We have taken a step in this direction focusing on the social, economic, political and historical circumstances that shape an individual’s experiences. Next steps that consider use of hierarchical linear modeling techniques that nest individuals within the historical era may further enhance our understanding of this phenomenon, as will analyses that include covariates such as health status, or consider population demographics across the defined eras.

Study Implications

Our findings suggest that understanding sociopolitical contexts at time of entry complements the country of emigration as Portes and others have described. Further, the context of entry may shed light on the ways that immigrants’ lives and health are influenced in the process of immigration, and how policies may affect the well-being of immigrant populations. Our findings suggest ways in which a guest worker program, such as the Bracero program, might affect the health of immigrants over time. Ideally, policymakers will consider the implications of their decisions for future mental health in these vulnerable populations.

Mixed methods approaches may help to elucidate, from immigrants’ own perspectives and lives, pathways through which their experiences affect health. Prospective studies and natural experiments observing the effect of changing immigration policies will help clarify how emigration and immigration influence individuals’ lives; access to health-sustaining opportunities, such as education and knowledgeable social networks; and ultimately, health outcomes. Conducting qualitative studies to capture binational experiences, at both time of exit and time of entry in the U.S. would also enhance our understanding of the many factors affecting health outcomes.

Conclusions

In this study, we examined an older Mexican-origin population that lived through multiple contexts. We found evidence that the social, economic, political and historical circumstances at the time of arrival to the U.S. are significantly, although modestly, associated with number of depressive symptoms among Mexican immigrants to the U.S. There are a variety of plausible mechanisms through which situations encountered in the course of immigration may influence psychological well-being later in life, including access to educational and economic opportunities as well as exposures to discrimination and harsh treatment, and thus health. Research limited to an examination of individual-level factors such as nativity or generational status may misattribute differences observed to individual, rather than sociopolitical factors. It is imperative that researchers seeking to influence health policy understand how to take contextual differences and their implications for health into account, so that the social and economic policy decisions made today may reduce future health inequalities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Kellogg Health Scholars Program, under a grant, P0117943, from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to the Center for Advancing Health, a dissertation grant from the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, and the Healthy Environments Partnership and its minority supplement grant, both from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (#R01 ES10936, #R01 ES014234). Dr. González is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH 67726 and MH 84994). The authors would like to thank Graciela Mentz for her statistical consultations.

References

- 1.Black SA. Increased health burden associated with comorbid depression in older diabetic Mexican Americans—results from the Hispanic established population for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly survey. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(1):56–64. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black SA, Markides KS. Depressive symptoms and mortality in older Mexican Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black SA, Markides KS, Miller TQ. Correlates of depressive symptomatology among older community-dwelling Mexican Americans: the Hispanic EPESE. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(4):S198–208. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider MG. The intersection of mental and physical health in older Mexican Americans. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2004;26(3):333–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider MG, Chiriboga DA. Associations of stress and depressive symptoms with cancer in older Mexican Americans. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4):698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace SP, Villa VM. Equitable health systems: cultural and structural issues for Latino elders. Am J Law Med. 2003;29(2–3):247–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bean FD, De la Garza R. At the crossroads: Mexican migration and U.S. policy. New York: Rowman and Littlefield; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Portes A, Escobar C, Radford AW. Immigrant transnational organizations and development: a comparative study. Int Migr Rev. 2007;41(1):242–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand J, Massey DS, Charvet F. The changing geography of Mexican immigration to the United States: 1910–1996. Soc Sci Q. 2000;81(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Garza R, Szekely G. Policy, politics and emigration: reexamining the mexican experience. In: Bean FD, et al., editors. The crossroads: Mexican migration and U.S. policy. New York: Rowman and Littlefield; 1997. pp. 201–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nevins J. Deportations of Mexican-origin people in the United States. In: Oboler S, Gonzalez DJ, editors. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 496–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acuna R. Occupied America: a history of Chicanos. 6. New York: Longman; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez OJ. The Border. In: Oboler S, Gonzalez DJ, editors. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Kelly P, Massey DS. Borders for whom? The role of NAFTA in Mexico-US migration. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2007;610:98–118. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson MC. The economic causes and consequences of Mexican immigration to the United States. Denver Univ Law Rev. 2007;84(4):1099–120. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massey DS. Social and economic aspects of immigration. In: Kaler SG, Rennert OM, editors. Understanding and optimizing human development: from cells to patients to populations. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 2004. pp. 206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery E, Foldspang A. Discrimination, mental problems and social adaptation in young refugees. Eur J Pub Health. 2008;18(2):156–61. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muntaner C, et al. Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:53–62. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Do negative emotions mediate the association between socioeconomic status and health? Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;896:226–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, Roszell P. Personal resources and the social distribution of depression. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(5):643–72. doi: 10.1023/A:1022189904602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. The stress process and the social distribution of depression. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(4):374–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: where we are and where we need to go. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2003;25(2):127–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills TL, Henretta JC. Racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic differences in the level of psychosocial distress among older Americans. Res Aging. 2001;23(2):131–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swenson CJ, et al. Depressive symptoms in Hispanic and non-Hispanic White rural elderly—the San Luis Valley health and aging study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(11):1048–55. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.11.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seligman ME, Maier SF. Failure to escape traumatic shock. J Exp Psychol. 1967;74(1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/h0024514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markides KS. Established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly, Wave I, 1993–1994 [Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas] Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 1993–1994. [distributor] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1997;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho MJ, et al. Concordance between 2 measures of depression in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1993;28(4):156–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00797317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neter J, et al. Applied linear statistical models. 3. Chicago: McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression—critical review. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:486–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zarit SH, Zarit JM. Mental disorders in older adults. New York: The Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen YY, et al. Women’s status and depressive symptoms: a multilevel analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzoli L, et al. Marital status and mortality in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(1):77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bolton P, et al. Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(5):519–27. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Jong K, et al. The trauma of ongoing conflict and displacement in Chechnya: quantitative assessment of living conditions, and psychosocial and general health status among war displaced in Chechnya and Ingushetia. Confl Health. 2007;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(7):1524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]