Abstract

The pathway by which inhaled NO gas enters pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells has not been directly tested. Although the expected mechanism is diffusion, another route is the formation of S-nitroso-L-cysteine, which then enters the cell through the L-type amino acid transporter(LAT). To determine if NO gas also enters alveolar epithelium this way, we exposed alveolar epithelial—rat type I, type II, L2, R3/1, and human A549—cells to NO gas at air liquid interface in the presence of L- and D-cysteine ± LAT competitors. NO gas exposure concentration-dependently increased intracellular NO and S-nitrosothiol levels in the presence of L- but not D-cysteine, which was inhibited by LAT competitors, and was inversely proportional to diffusion distance. The effect of L-cysteine on NO uptake was also concentration dependent. Without pre-incubation with L-cysteine, NO uptake was significantly reduced. We found similar effects using ethyl nitrite gas in place of NO. Exposure to either gas induced activation of soluble guanylyl cylase in a parallel manner, consistent with LAT-dependence. We conclude that NO gas uptake by alveolar epithelium achieves NO-based signaling predominantly by forming extracellular S-nitroso-L-cysteine that is taken up through LAT, rather than by diffusion. Augmenting extracellular S-nitroso-L-cysteine formation may augment pharmacological actions of inhaled NO gas.

Keywords: S-nitrosoethanol, ethyl nitrite, L-type amino acid transport, nitric oxide therapy, alveolar epithelium

Introduction

It has been assumed that nitric oxide gas gains entry to the lung through diffusion, since nitric oxide is readily diffusible through lipids[1]. However, the gas exchange surface of the lung exists predominantly surmounted by the alveolar lining fluid, which may contain components that could interact with (glutathione, cysteine) or inactivate nitric oxide(reactive oxygen species[2]), posing a potential barrier to inhaled NO entry into alveolar epithelium and subsequent therapeutic action.

Instead, we propose that NO gas gains entry into alveolar epithelium primarily by the extracellular formation of the S-nitrosothiol, SNO-L-cysteine, which enters via the L-type amino acid transporter (LAT). We have previously shown that NO released by NO-donating compounds can gain entry into pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells in vitro by this route[3]. This scheme has also been demonstrated for nitric oxide equivalent uptake into non-lung cell types[4, 5]. While nitric oxide mediated biological actions have been extensively studied, relatively few studies have addressed alveolar epithelial cellular uptake of nitric oxide gas and activity in the context of pharmacologic treatment. In general, studies using physiologic tracer gas approaches such as 15N-enriched nitric oxide[6] or nitric oxide gas analysis have shown that inhaled nitric oxide gas uptake by the lung in disease states may be reduced, particularly in conditions with alterations in alveolar dead space[7]. To our knowledge, nitric oxide gas uptake by alveolar epithelial cells has not been studied.

We therefore sought to determine whether treatment of alveolar epithelium at air liquid interface with nitric oxide gas at clinically relevant concentrations would depend on alveolar epithelial uptake of nitric oxide as SNO-L-cysteine via LAT. We conducted studies using rat alveolar epithelial cells, as well as human A549 cells, exposed to nitric oxide (NO) gas or to O-nitrosoethanol (ethyl nitrite, ENO) gas, which more readily forms S-nitrosothiols (SNO) than NO gas[8], in order to more closely model the physical and chemical barriers to NO and ENO gas entry to alveolar cells. We found that NO or ENO gas achieved maximum intracellular NO and SNO concentrations and guanylyl cyclase (EC: 4.6.1.2) activity in alveolar epithelial cells by entry through LAT, with significantly lower uptake in the absence of L-cysteine or in the presence of LAT competitors.

Methods

Materials

Reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) except where otherwise noted. Rat type I-like alveolar epithelial cells (R3/1 cells) were a gift from R. Koslowski (Dresden, Germany) [9]. Rat type II-like alveolar epithelial cells (L2 cells) and human alveolar epithelial carcinoma-derived A549 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Nitric oxide, oxygen, and nitrogen gases were obtained from National Specialty Gases (Durham, NC). ENO gas was obtained from Custom Gas Solutions (Durham, NC). Anti-LAT1 was obtained from Cosmo Bio USA, (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-pro-SP-C, anti-caveolin, and anti-aquaporin 5 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz CA). Anti-T1α (anti-rat podoplanin) was obtained from Sigma. Secondary antibodies labeled with AlexaFluor 488, 4-amino-5-methylamino-2,7-difluorofluoroscein diacetate (DAF-FM), and cell culture media were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Cell culture flasks, plates, and wells were from Costar (Corning, NY).

Primary rat alveolar epithelium isolation

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult Sprague-Dawley rats (200–300 g) were obtained from Charles River (Raleigh, NC). Type I alveolar epithelial cells (AEC 1) and type II alveolar epithelial cells (AEC 2) were isolated using anti-T1α and anti-pro-SP-C coated magnetic beads according to the method of Chet et al., [10] with modifications we have previously described in detail [3]. Purity of cell populations was verified by immunolabeling cytospin preparations with anti-T1 α, anti-caveolin, and anti-aquaporin 5, to detect AEC 1, and the presence of anti-pro-SP-C labeling but absence of AEC 1 marker labeling for AEC 2. Labeling was detected by immunoflourescence using the appropriate secondary antibodies labeled with AlexaFluor 488. Studies using isolated AEC 1 and AEC 2 were used within 72 h of isolation.

Expression of L-type amino acid transporter-1

Cytospin preparations of each cell type were labeled with polyclonal rabbit-anti-human LAT-1, followed by detection using secondary goat-anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor 488. Protein was extracted from whole cell lysates, and subjected to SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and chemiluminescence detection as previously described in detail [3].

Air-liquid interface (ALI) gas exposure system

Culture conditions for AEC 1 and AEC 2 were as previously described [3]. R3/1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium and L2 cells were cultured in F-12 Kaighn’s medium. Media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10,000 units of penicillin, and 10 mg of streptomycin/ml. Cells were maintained in T-75 flasks and used at passage 9–12 for R3/1 cells and 43–50 for L2 cells. For SNO measurement studies, cells were plated in 24 mm transwell plates pre-coated with rat tail collagen, and maintained in suspension until confluent. For gas or NO donor exposures, test buffers contained HBSS, 0.2 mM glutathione, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, as well as the indicated amino acids, competitors and inhibitors at the indicated volumes. In preliminary studies, trypan blue was added to cells to determine the viability under each experimental condition after NO/ENO gas exposure. The pH of the cell buffer after adding amino acids and inhibitors were confirmed to be 7.2–7.4. Gas exposures were performed in a Billups-Rothenberg (San Diego, CA) chamber using a constant 2.5 liter/min flow to avoid accumulation of higher order nitrogen oxides. Gases were administered using mass flow controllers (Aalborg Instruments, Orangeburg, NY) for each gas, as previously described [11]. Cells were exposed to air, nitric oxide, or ENO gas (2–20 ppm) at 37°C with 21% medical grade O2 and nitrogen as the balance gases for the specified durations.

Nitric oxide uptake: DAF-FM fluorescence

Just before adding apical test buffers, cells were incubated with 5 µM DAF-FM for 45 min, and rinsed by incubating in HBSS for 15 min. DAF-FM diacetate undergoes de-esterification to form DAF-FM, impermeant to cell membranes, which reacts with nitric oxide to yield a fluorescent product. Cells were then overlain with test buffers containing L- or D-cysteine (L- or D-Cys) ± LAT competitors L-leucine (L-Leu) 10 mM or 2-amino-2-norborane carboxylic acid (BCH) 10 mM. To confirm dependence of NO/SNO uptake through the sodium-independent LAT, choline chloride was substituted for sodium chloride in the test buffer [12]. To exclude a major contribution of endogenous NO production, control incubations were performed in the presence of 100 µM L-NG-monomethyl arginine (L-NMMA), a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor. Except were otherwise indicated, cells grown on 24 well inserts were overlain with 100 µl and those grown in 6 well inserts were overlain with 160 µl to achieve comparable diffusion distances. DAF-FM fluorescence measurements were made in a plate reader at 490 nm (TECAN, Salzburg, Austria), and normalized to cell number estimated by incubation with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen), a fluorescent dye that detects DNA, as we have previously described [3]. Fluorescence values from 8 wells/condition were then normalized to the maximum mean value after subtracting background fluorescence from buffer-only wells before calculating mean values. Cellular SNO was measured using the tri-iodide chemiluminscense as we have previously described in detail [3]. After exposure to treatment gas, cells grown in six well inserts were exposed to treatment gas, washed, and then scraped with buffer containing 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide and 0.1 mM diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid followed by sonication and centrifugation. Supernatants were treated with 50 mg/ml sulfanilamide to remove nitrite and analyzed for SNO concentrations (in the presence and absence of 5 mM HgCl2) in duplicate. Aliquots of the lysate supernatant were analyzed for total protein by the Bradford method. SNO measurements were normalized to cellular lysate protein concentration. Freshly prepared S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) was used to generate SNO standards. To verify that other nitrogen-oxygen moieties that can be generated during the triiodide chemiluminescence analysis were not major contributors to apparent gas-exposure induced SNO uptake[13], we repeated some experiments in which SNO was measured by the UV photolysis method as previously described in detail [14].

Modification of diffusion distances

We varied the apical buffer volumes used during gas exposures in order to determine if diffusion distance played a significant role in NO/SNO uptake. Since the reported alveolar lining thickness can vary,[15, 16] we sought to determine if LAT transport is important to NO uptake even with a very short diffusion distance. To accomplish this, we cultured R3/1 or L2 cells as above, and incubated them at air liquid interface (ALI) with the indicated amino acids and competitors in the apical buffer at the specified volumes (0–320 µl) for 15 minutes. In order to achieve the minimum possible diffusion distance, we then carefully removed the apical incubation buffer immediately before exposing to NO or ENO gas.

Guanylyl cyclase activity

Cells cultured in 6.5 mm transwell inserts were exposed to test gases at ALI using the indicated apically applied test buffers that also contained 0.3 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. For analysis of soluble guanylyl cyclase activity, cells were lysed in cold 6% trichloroacetic acid, then centrifuged according to the manufacturer’s directions. The concentrations of cGMP were determined by immunoassay with and without the guanylyl cyclase inhibitor 1H-[17]oxadiazolo[18] qunoxalin-1-one (ODQ), to verify specificity (cGMP Immunoassay Biotrak System, GE Healthcare, Piscataway NJ). To eliminate any contribution of endogenous NO synthesis, cells were co-incubated with 100 µM L-NMMA as described above. Replicate experiments were performed substituting 50 µM spermine NONOate or GSNO for NO or ENO gas as positive controls.

Results

Expression of LAT in alveolar epithelial cells

Primary cell isolation of AEC1 and AEC2 resulted in populations that were routinely over 90% pure, determined by immunolabeling with antibodies directed against T1α, aquaporin 5, and caveolin in AEC1, and pro-SP-C in AEC2. LAT1 was expressed in all alveolar epithelial cell types tested: AEC1, AEC2, L2, R3/1, and A549 cells, determined by immunocytochemistry and western blot (Supplemental Fig. 1).

LAT inhibition effects on NO/SNO uptake in alveolar epithelium exposed to NO/ENO gases

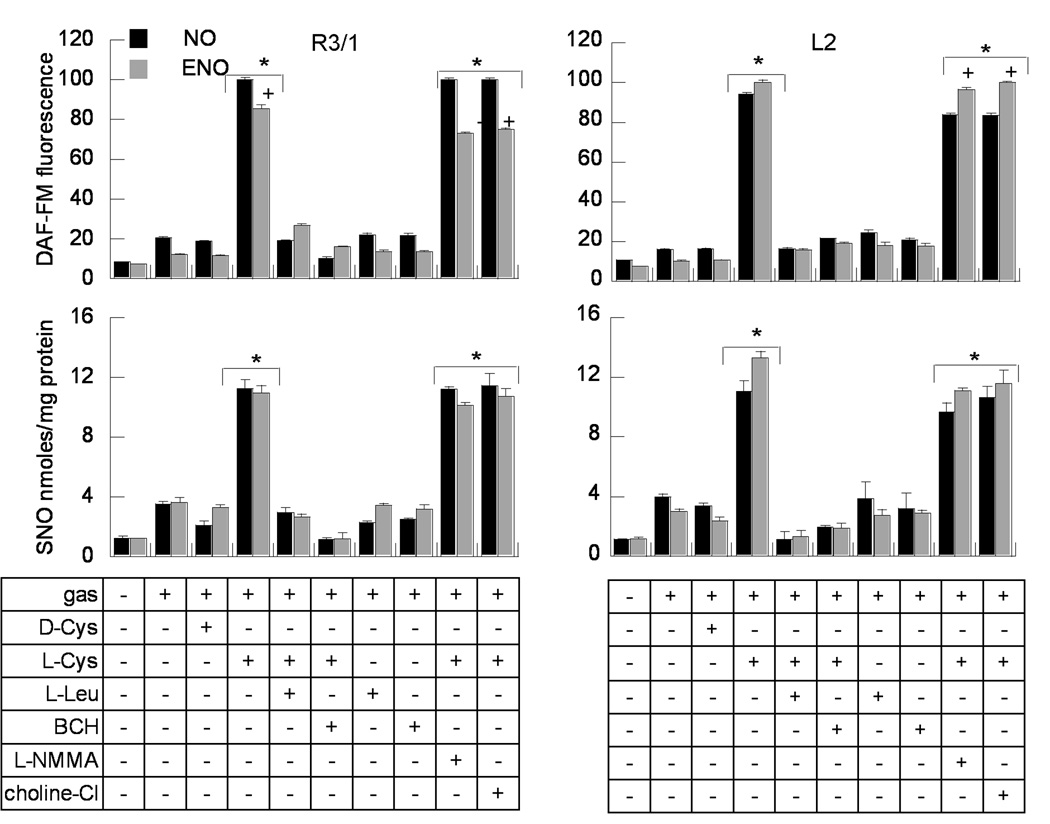

Exposure to NO or ENO gas induced maximum NO and SNO accumulation in all alveolar epithelial cell types only in the presence of L-Cys, not D-Cys, consistent with stereospecific transport. Augmentation of NO/SNO uptake by L-Cys was completely inhibited by LAT competitors L-Leu and BCH (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 2). The augmentation of NO/SNO uptake by L-Cys and its blockade with LAT competitors was unaffected when choline chloride was substituted for sodium chloride in the incubation buffer, indicating sodium-independent transport. NO/SNO accumulation under these conditions was not affected by inhibition of endogenous NO production with L-NMMA. At the same concentrations, 10 ppm, NO gas treatment induced greater DAF-FM signal than ENO in R3/1 cells, but without corresponding significant changes in SNO uptake. In contrast, ENO exposure induced higher DAF-FM fluorescence than NO in L2 cells. We found no significant disparities between the maximum SNO levels measured by triiodide chemiluminescense or ultraviolet photolysis methods (not shown).

Figure 1.

NO and SNO uptake in R3/1 and L2 cells at ALI, exposed to NO or ENO gases, 10 ppm. Upper panel. DAF-FM fluorescence ± 100 µM D- or L-cysteine, or LAT competitors L-leucine or BCH ( 10 mM). Cells were also incubated with L+Cys + 100 µM L-NMMA, or in the presence of buffer containing choline chloride in place of NaCl. DAF-FM fluorescence was divided by the cell number approximated with Hoechst 33342 fluorescence. Relative fluorescence values are normalized to the maximum DAF-FM signal produced by each gas exposure. Data are mean + SE for 16 wells/condition. Lower panel. SNO detected by the triiodide chemiluminescence method, normalized to cell lysate protein content. Data presented are mean + SEM, n=6 wells/condition. *p<.01, L-Cys v. D-Cys, +p<.05, NO v. ENO exposure.

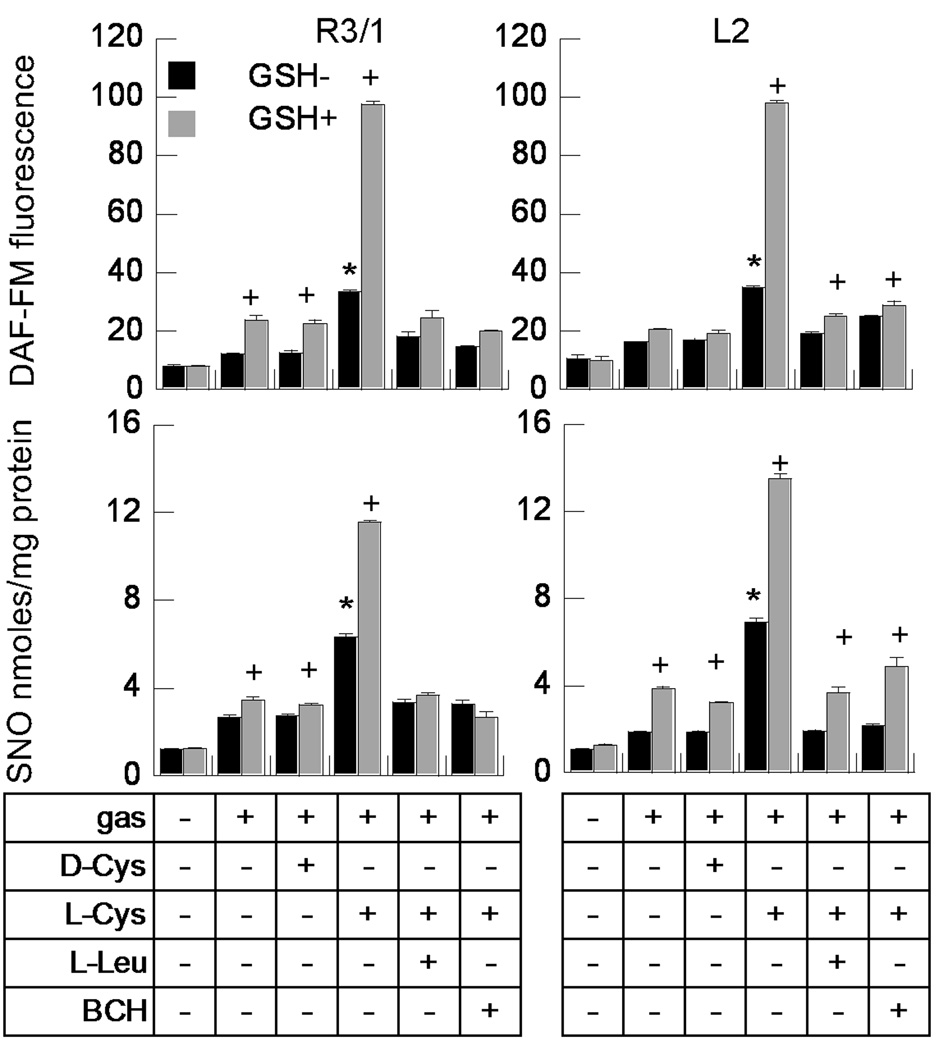

Effect of Glutathione (GSH) on NO/SNO uptake in alveolar epithelium exposed to NO/ENO gases

We examined the effect on NO uptake by adding GSH (0.2mM) to L-and D-Cys. We found that the addition of glutathione in the absence of added L-Cys had small but statistically significant effects on NO and SNO uptake in R3/1 and L2 cells exposed to NO gas (Fig. 2). Results were parallel after exposure to ENO gas (see Supplemental Fig. 3). Adding 0.05mM L-Cys alone showed greater augmentation of NO and SNO uptake in both cell types than did GSH alone. The combination of GSH and L-Cys, but not D-Cys had significantly greater effects. Treatment with LAT competitors completely blocked the L-Cys and GSH augmented NO and SNO uptake in R3/1 cells, but did not completely block GSH augmented uptake in L2 cells.

Figure 2.

Effect of glutathione ± L-Cys on NO (upper panels) and SNO (lower panels) uptake. R3/1 and L2 cells were incubated with buffer alone, 100 µM D- or L-Cys, or L-Cys ± L-Leu or BCH (10 mM), in the absence (GSH-) or presence (GSH+) of 0.2mM glutathione. Data are mean + SEM, n=7–8 wells/condition, *p<.01 v. D-Cys, + p<.01 v. corresponding treatment with L-Cys alone.

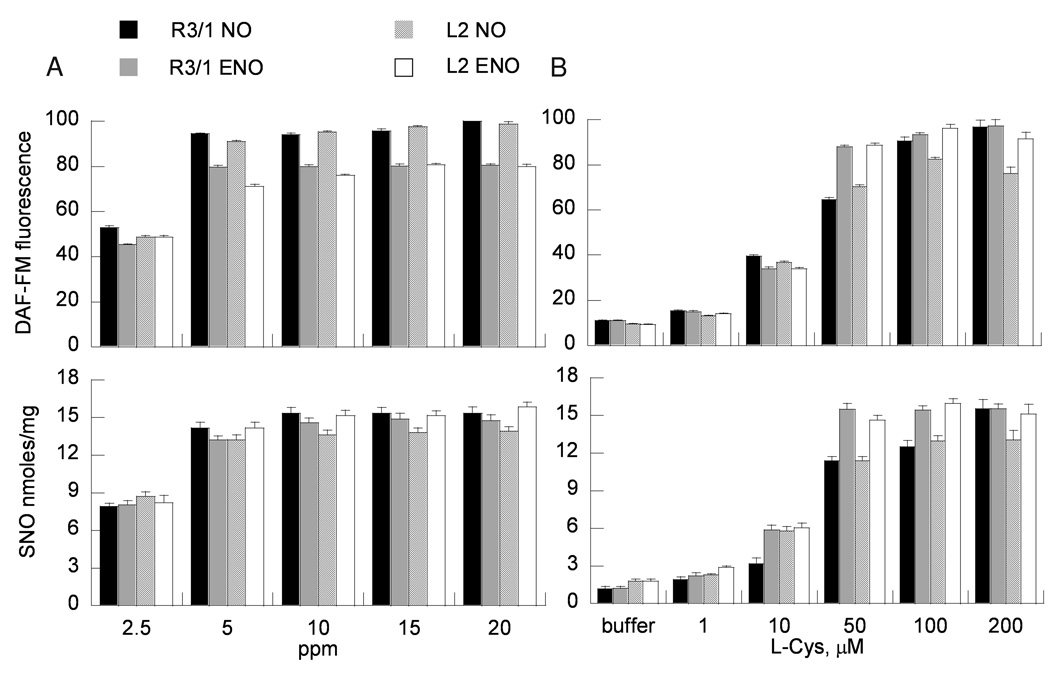

NO/ENO and L-Cys concentration effects on NO/SNO uptake in alveolar epithelium

Exposure of R3/1 and L2 cells at ALI to either NO or ENO gas (2.5–20 ppm) for 4 hours demonstrated concentration dependent increases in cellular NO and SNO content with a plateau at 10 ppm (Fig. 3). L-Cys added to the apical buffer concentration-dependently augmented NO/SNO uptake in epithelial cells exposed to NO or ENO 10 ppm. Significant effects were observed beginning at 10 µM L-Cys in R3/1 and L2 cells (at 5 µM in A549 cells, Supplemental Fig. 4), with increased DAF-FM fluorescence and SNO levels, until a plateau was achieved at 100 µM in all alveolar epithelial cell types.

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of (A) NO/ENO gas (100 µM L-cysteine) or (B) L-cysteine concentrations (gases at 5 ppm) on NO (upper panels) and SNO (lower panels) uptake in alveolar epithelial cells. Data are mean + SEM, n=8 for DAF-FM, mean + SEM, n=4 for triiodide chemiluminescence measurements.

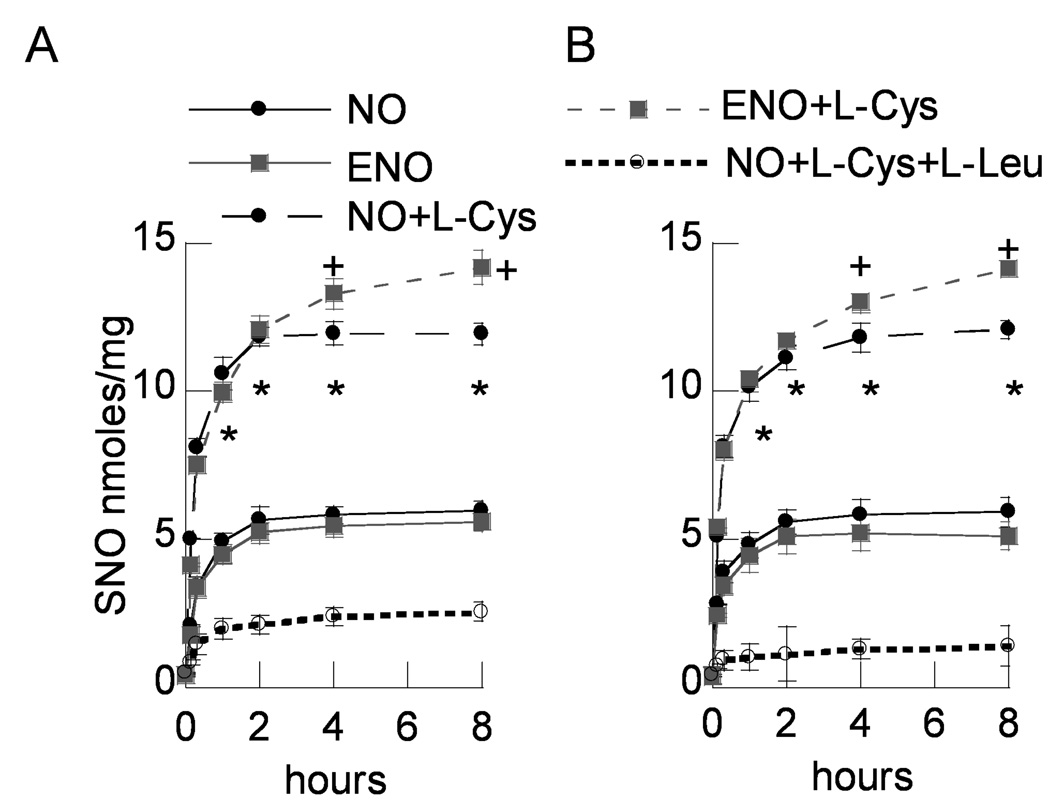

Time-dependent accumulation of SNO in R3/1 and L2 cells ± LAT inhibition

Significant, immediate, time-dependent increases of SNO were observed in both R3/1 and L2 cells upon exposure to NO or ENO 10 ppm in the presence of 100 µM L-cysteine. NO exposed cells demonstrated a plateau of SNO accumulation at 2 h which persisted to 8 h, whereas ENO exposed cells continued to accumulate SNO up to 8 h. SNO accumulation after NO or ENO gas exposure was significantly less without co-incubation with L-cysteine, and was markedly inhibited by co-incubation with LAT competitors (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

SNO determined by triiodide chemiluminescence accumulation v. time in NO and ENO exposed (A) R3/1 cells and (B) L2 cells in the presence of L-Cys ± LAT competitor L-Leu. Data are mean ± SEM of 3 replicate experiments, *p<.05 v. gas only and gas+L-Cys+L-Leu for both NO and ENO exposed cells.

Diffusion barrier effect on NO/ENO gas exposure induced NO/SNO uptake

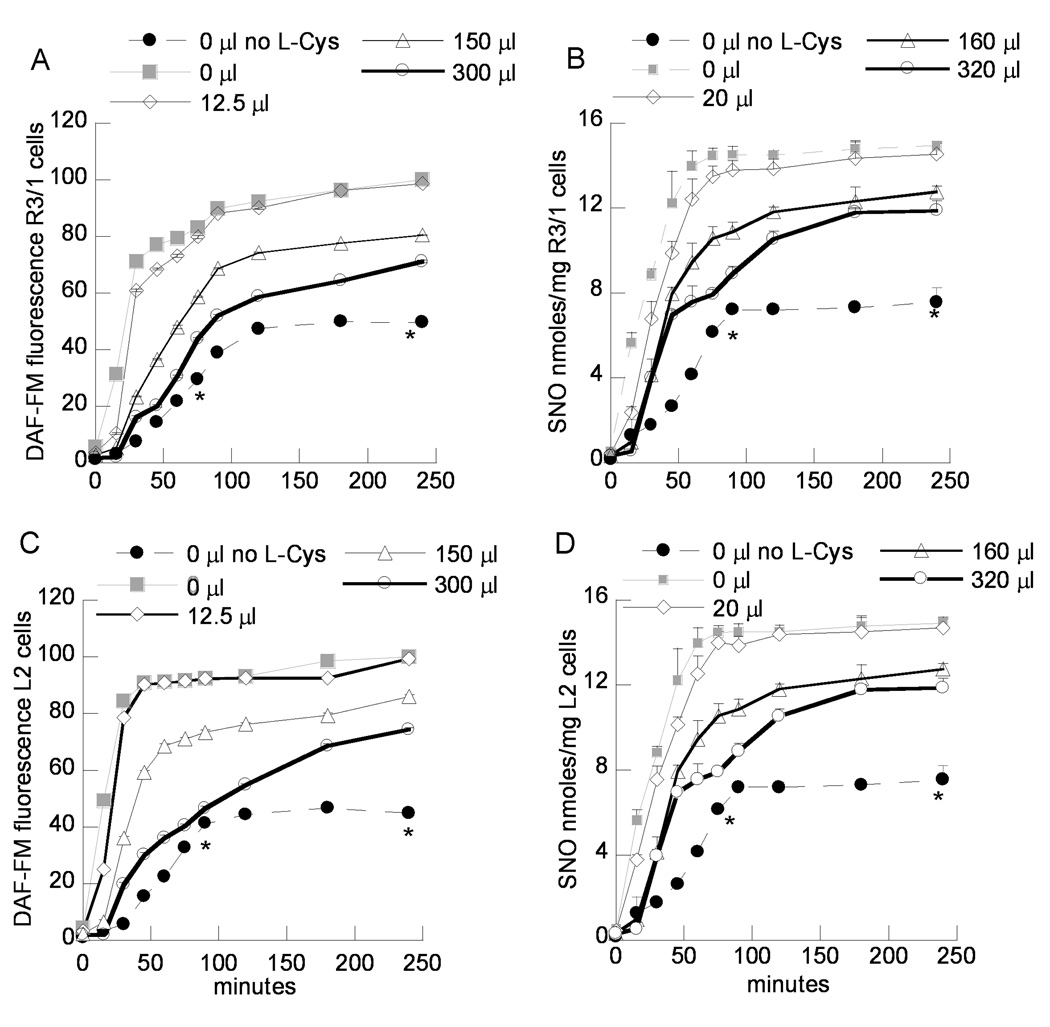

Apical buffer volumes in the culture inserts were adjusted to vary the diffusion path lengths from the incubation gas to the intracellular compartment. We found that increasing the apical buffer volumes during NO (Fig. 5) or ENO gas exposure (Supplemental Fig. 5) decreased the DAF-FM and SNO levels in R3/1 and L2 cells. However, even when the apical incubation buffer was completely removed from cells before incubation with gas (0 µl), we found that NO and SNO accumulation following NO or ENO gas exposure was LAT-dependent. When diffusion distances were low (apical buffer volumes < 50 µl), SNO accumulation reached a plateau by 60–75 minutes. By 3 hours, SNO accumulation in ENO exposed R3/1 and L2 cells was similar for all buffer volumes, whereas in NO exposed cells, SNO accumulation continued to show dependence on diffusion distance. The results were similar for A549 cells (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of apical buffer volume on NO gas- induced DAF-FM fluorescence (A, C) and SNO (B, D) (chemiluminescence) after gas exposure in R3/1 (A, B) or L2 cells (C,D). Cells were exposed to NO 10 ppm, with the indicated apical buffer volumes that included L-Cys 50 µM. For the “0 µl” conditions, apical buffer was completely removed just before gas exposure. DAF-FM data are mean of 8 wells + SEM, SNO data are mean of 3 experiments + SEM. *p<.05 v. cells incubated with L-Cys.

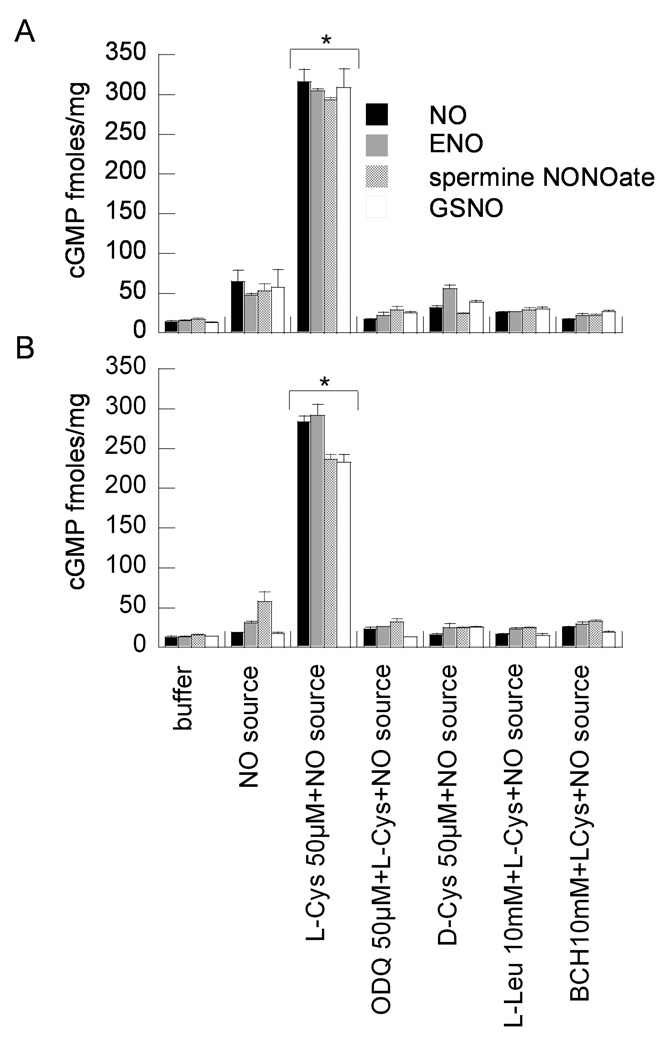

LAT inhibition effects on NO and ENO gas augmented guanylyl cyclase activity

Both NO and ENO gas at 5 ppm maximally augmented sGC activity in R3/1, L2, (Fig. 6) and A549 cells (Supplemental Fig. 6) in the presence of L- but not D-Cys. This effect was abolished when cells were incubated in the presence of sGC inhibitor ODQ, and was independent of NOS, since studies were performed in the presence of L-NMMA. The L-Cys augmented sGC activity was completely inhibited in the presence of LAT competitors L-Leu or BCH. Cyclic GMP levels in NO or ENO 5 ppm exposed cells in the presence of L-Cys were comparable to the GSNO and spermine NONOate positive controls. This was also observed when the apical buffer was removed after incubation with competitors and amino acids immediately before incubation in gas in order to minimize the diffusion barrier (Supplemental Fig. 7).

Figure 6.

Effect of LAT inhibition on NO/ENO gas (5 ppm) augmented guanylyl cyclase activity in (A) R3/1 and (B) L2 cells. Data are mean + SEM of 3 measurements. Positive controls are cells incubated with NO donors spermine NONOate or GSNO (50 µM). Cells were incubated with sGC inhibitor ODQ to verify enzyme-dependence of effects on cGMP concentrations.

Discussion

Although inhaled NO is used widely for a variety of clinical conditions, the precise pathways from the inhaled NO molecule to its pharmacologic effects have not been completely mapped. In order to better understand the first steps, which include NO uptake by the lung alveolus, we tested the route by which NO gas enters type I and type II alveolar epithelium, since they comprise the overwhelming majority of the gas exchange surface [19]. We found that NO gas exposure achieved maximum intracellular NO and SNO only in the presence of L-Cys in the alveolar epithelial cell types tested: rat AEC1, AEC2, R3/1, L2, and human A549 cells. The maximum uptake required co-incubation of L-Cys in the presence of glutathione, which further enhanced NO/SNO uptake compared with incubation in the presence of L-Cys alone. Incubation with gluathione alone had a much smaller effect. Since treatment with LAT competitors did not completely eliminate NO uptake, S-nitrosylated glutathione may have been metabolized to S-nitrosocysteinyl glycine, which could have entered cells via petide transporter 2 (PEPT2). Alternatively, glutathione may have simply served as a reducing agent, protecting against oxidation of NO.

Since the effects on NO/SNO uptake were dependent on the concentration of NO or ENO gas, and on L-Cys, but not D-Cys, in buffer, and were inhibited by LAT competitors L-Leu and BCH, we conclude that L-Cys undergoes S-nitrosation in the apical extracellular buffer to form SNO-L-Cys which is taken up via stereoselective amino acid transport through LAT. We verified that NO and ENO gases formed SNO even in a cell-free buffer system in the presence of D- or L-Cys (data not shown).

Although L-Cys uptake through other membrane transporters—e.g., system XAG−, system ASC—known to be present in alveolar epithelium has been demonstrated,[12] all except LAT are sodium-dependent. Since we found that substitution of choline chloride for sodium chloride had no effect on L-Cys-dependent NO/SNO uptake after NO or ENO gas exposure, we conclude that NO uptake in alveolar epithelium is LAT-dependent.

We showed that the NO-equivalent mediated activation of guanylyl cylase is dependent on SNO uptake through LAT in alveolar epithelium. This was true for NO and ENO gases, as well as in vitro incubation with GSNO or spermine NONOate in the apical buffer. These findings add to the growing body of evidence that contradicts the idea that NO passively diffuses in biological systems in order to activate guanylyl cyclase [20] and to form other biologically relevant adducts like SNO [21]. Instead, our observations demonstrate that the major gateway for NO gas entry to alveolar epithelium sufficient to achieve biologically relevant signaling is via LAT rather than simple diffusion. Even activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase, which has been used as a canonical detector of NO-mediated biological activity [22], has been shown to be dependent on transport of SNO-L-Cys via LAT in some cell systems [20].

Because SNOs mediate a substantial array of NO-driven biological functions [23], we performed similar studies using ENO gas, since ENO has been shown previously to achieve SNO formation in vitro more readily than NO gas [8]. ENO gas treatment can also replete airway SNO in experimental models [11, 14] that might inactivate NO. Like NO, ENO gas achieved the greatest intracellular NO and SNO levels in the presence of L-Cys. With prolonged exposures (>4 h), ENO gas induced greater SNO accumulation than NO in R3/1 and L2 cells (Fig. 4). Since we did not observe substantial differences in accumulation immediately upon exposure, it seems unlikely that there are major differences in the abilities of NO and ENO gas to diffuse into cells. On the other hand ENO achieves S-nitrosation without releasing NO, so it would be less vulnerable to superoxide attack [8], which could contribute to the observed differences in accumulation with longer exposure durations. We do not know if these differences are physiologically relevant, or would persist under conditions of significant oxidative stress. ENO gas treatment was superior to NO gas treatment in preventing adverse hyperoxia effects on postnatal rat lung development [11].

Conclusions about NO gas uptake and effects are necessarily limited by our model system. Pulmonary alveolar gas exchange—including therapeutically administered NO gas—takes place across a surfactant layer which overlies the aqueous hypophase that surmounts the alveolar epithelium. The liquid layer in the lung is believed to be on the order of 1 µm thick, although it would be expected to vary [15, 16]. Lining fluid thicknesses as low as 0.09 µm have been shown in normal adult rat lungs, but these dimensions may be less common in clinical conditions for which NO is believed to be useful, and dynamic imaging of alveolar lining fluid ex vivo demonstrated alveolar lining fluid thicknesses ~2–8 µm in non-pathologic conditions [16]. Typically ALI culture systems using alveolar epithelium employ a bare membrane exposed directly to gas [24]. Since we were focused on the biochemical and physical barriers to NO gas uptake that are likely present in the pulmonary alveolus, we used apical buffer volumes that would provide an average buffer layer thickness between 0–20 µm containing physiologically relevant concentrations of glutathione[2] and cysteine[25]. Although we believe we chose diffusion distances in the range of the alveolar lining fluid thickness that would be expected under a variety of pathological conditions, there are few data to guide us. Nevertheless, the LAT-dependency of NO and SNO uptake by alveolar epithelium after NO and ENO gas exposure was present even when we completely removed apical buffers just before gas exposure.

We found that transport of NO/SNO via LAT was the dominant pathway for NO activity uptake after NO or ENO gas exposure when we used L-Cys concentrations comparable to those demonstrated in vivo (Lou Ann Brown, personal communication) [26]. Even at L-Cys <20 µM, NO uptake showed concentration dependence (Supplemental Fig. 4). However, the relative contribution of this pathway compared with NO gas diffusion at low cysteine concentrations is unknown. Our findings cannot exclude a role for pharmacologically relevant NO gas diffusion into alveolar epithelium in all conditions. Indeed, we were able to detect intracellular DAF-FM and SNO in R3/1 cells, as well as sGC activation in L2 cells after exposure to NO or ENO gas in the absence of added L-Cys, following removal of apical buffer. However the maximum SNO concentrations were less than half of those observed in cells incubated with L-Cys before removal of apical buffer (Fig. 5). The relative contributions of NO transport via diffusion versus transport may vary depending on local redox conditions in various disease states that would affect oxidation of NO or cysteine.

We observed no changes in cell morphology, cell adhesion, or trypan blue exclusion, even after 8 h of NO or ENO exposure (data not shown). We did not examine cellular function in detail. The levels of SNO we observed in epithelial cells following exposure to NO or ENO gas have been associated with toxicity in non-pulmonary cell types, such as neurons [27, 28]and hepatocytes [29]. We cannot exclude more subtle adverse effects of augmented NO or ENO uptake and SNO accumulation. Because of their critical role in enzyme regulation, it is likely that “adaptive” concentrations of SNOs differ between cell types under varying conditions.

NO or ENO gas exposure in our system would also be expected to produce GSNO [8] in the apical buffer, a substrate for γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (EC: 2.3.2.2), an enzyme expressed in alveolar epithelium [26] that produces cysteinylglycine. The dipeptide transporter PEPT2, also expressed in alveolar epithelium [3, 30], can import SNO-cysteinylglycine, but we found no significant DAF-FM fluorescence elevation or increases in SNO accumulation when LAT was blocked, even after relatively long incubations (>4h), suggesting that SNO uptake following NO/ENO gas exposure through PEPT2 is probably minor, although we did not test this directly. Our previous studies showed no significant SNO uptake through PEPT2 in alveolar epithelium following exposure to GSNO or SNO-cysteinylglycine, but it is possible that longer culture durations of the primary isolated alveolar epithelial cells would result in sufficient γ-glutamyl transpeptidase expression [26] that would be necessary for SNO-cysteinylglycine production.

In summary, we have shown that clinically relevant concentrations of NO gas gain entry into alveolar epithelium at ALI and activate NO-dependent sGC by forming SNO-L-Cys which is transported into the cells via LAT. Increasing the apical buffer L-Cys concentration increased the NO uptake by alveolar epithelium exposed to NO or ENO gas. ENO gas also requires entry through LAT as SNO-L-Cys for maximal effects on NO and SNO concentrations, and uptake of both gases to form SNO is impeded with increased diffusion distance. With prolonged exposure, ENO treatment led to greater SNO accumulation in R3/1 and L2 cells. We speculate that topical treatment with L-Cys could improve NO or ENO gas therapeutic potency in conditions where alveolar SNO formation is inhibited.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by R01HL-079915 (TJM), R01HL-088529 (ARW), and the March of Dimes (RLA). We thank Dr. Roland Koslowski, Technische Universität Dresden, for his generous gift of the R3/1 cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lancaster JR. The physical properties of nitric oxide. In: Ignarro LJ, editor. Nitric oxide biology and pathobiology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross CE, van der Vliet A, O'Neill CA, Louie S, Halliwell B. Oxidants, antioxidants, and respiratory tract lining fluids. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102 Suppl 10:185–191. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granillo OM, Brahmajothi MV, Li S, Whorton AR, Mason SN, McMahon TJ, Auten RL. Pulmonary alveolar epithelial uptake of S-nitrosothiols is regulated by L-type amino acid transporter. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L38–L43. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00280.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, Whorton AR. Identification of stereoselective transporters for S-nitroso-L-cysteine: role of LAT1 and LAT2 in biological activity of S-nitrosothiols. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20102–20110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broniowska KA, Zhang Y, Hogg N. Requirement of transmembrane transport for S-nitrosocysteine-dependent modification of intracellular thiols. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33835–33841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603248200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heller H, Korbmacher N, Gabler R, Brandt S, Breitbach T, Juergens U, Grohe C, Schuster KD. Pulmonary 15NO uptake in interstitial lung disease. Nitric Oxide. 2004;10:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westfelt UN, Lundin S, Stenqvist O. Uptake of inhaled nitric oxide in acute lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:818–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moya MP, Gow AJ, McMahon TJ, Toone EJ, Cheifetz IM, Goldberg RN, Stamler JS. S-nitrosothiol repletion by an inhaled gas regulates pulmonary function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5792–5797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091109498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koslowski R, Barth K, Augstein A, Tschernig T, Bargsten G, Aufderheide M, Kasper M. A new rat type I-like alveolar epithelial cell line R3/1: bleomycin effects on caveolin expression. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;121:509–519. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Chen Z, Narasaraju T, Jin N, Liu L. Isolation of highly pure alveolar epithelial type I and type II cells from rat lungs. Lab Invest. 2004;84:727–735. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auten RL, Mason SN, Whorton MH, Lampe WR, Foster WM, Goldberg RN, Li B, Stamler JS, Auten KM. Inhaled Ethyl Nitrite Prevents Hyperoxia-Impaired Postnatal Alveolar Development in Newborn Rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-662OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang X, Ingbar DH, O'Grady SM. Selectivity properties of a Na-dependent amino acid cotransport system in adult alveolar epithelial cells. 2000:L911–L915. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hausladen A, Rafikov R, Angelo M, Singel DJ, Nudler E, Stamler JS. Assessment of nitric oxide signals by triiodide chemiluminescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall HE, Potts EN, Kelleher ZT, Stamler JS, Foster WM, Auten RL. Protection from lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury by augmentation of airway S-nitrosothiols. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:11–18. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1186OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 15.Bastacky J, Lee CY, Goerke J, Koushafar H, Yager D, Kenaga L, Speed TP, Chen Y, Clements JA. Alveolar lining layer is thin and continuous: low-temperature scanning electron microscopy of rat lung. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:1615–1628. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.5.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindert J, Perlman CE, Parthasarathi K, Bhattacharya J. Chloride-dependent secretion of alveolar wall liquid determined by optical-sectioning microscopy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:688–696. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0347OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abe MK, Chao TS, Solway J, Rosner MR, Hershenson MB. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase in bovine tracheal myocytes: implications for human airway disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:577–585. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.5.7946386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryan-Lluka LJ, Papacostas MH, Paczkowski FA, Wanstall JC. Nitric oxide donors inhibit 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) uptake by the human 5-HT transporter (SERT) Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:63–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massaro DJ, Massaro GD, Clerch LB. Pulmonary Alveoli: Development, Structural Stability, and Regeneration. In: Massaro DJ, Massaro GD, Chambon P, editors. Lung Development and Regeneration. New York, NY: Marcell Dekker; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riego JA, Broniowska KA, Kettenhofen NJ, Hogg N. Activation and inhibition of soluble guanylyl cyclase by S-nitrosocysteine: involvement of amino acid transport system L. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gow AJ. The biological chemistry of nitric oxide as it pertains to the extrapulmonary effects of inhaled nitric oxide. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:150–152. doi: 10.1513/pats.200506-058BG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui X, Zhang J, Ma P, Myers DE, Goldberg IG, Sittler KJ, Barb JJ, Munson PJ, Cintron Adel P, McCoy JP, Wang S, Danner RL. cGMP-independent nitric oxide signaling and regulation of the cell cycle. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manzer R, Wang J, Nishina K, McConville G, Mason RJ. Alveolar epithelial cells secrete chemokines in response to IL-1beta and lipopolysaccharide but not to ozone. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:158–166. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0205OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry MH, McAllister BP, Jean JC, Brown LA, Hughey RP, Cruikshank WW, Amar S, Lucey EC, Braun K, Johnson P, Wight TN, Joyce-Brady M. Lung lining fluid glutathione attenuates IL-13-induced asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:509–516. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0128OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ingbar DH, Hepler K, Dowin R, Jacobsen E, Dunitz JM, Nici L, Jamieson JD. gamma-Glutamyl transpeptidase is a polarized alveolar epithelial membrane protein. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:L261–L271. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.2.L261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatokun AA, Stone TW, Smith RA. Prolonged exposures of cerebellar granule neurons to S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) induce neuronal damage independently of peroxynitrite. Brain Res. 2008;1230:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He J, Wang T, Wang P, Han P, Yin Q, Chen CA. novel mechanism underlying the susceptibility of neuronal cells to nitric oxide: the occurrence and regulation of protein S-nitrosylation is the checkpoint. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1863–1874. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Sanchez LM, Collado JA, Corrales FJ, Lopez-Cillero P, Montero JL, Fraga E, Serrano J, De La Mata M, Muntane J, Rodriguez-Ariza A. S-Nitrosation of proteins during D-galactosamine-induced cell death in human hepatocytes. Free Radic Res. 2007;41:50–61. doi: 10.1080/10715760600943918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groneberg DA, Nickolaus M, Springer J, Doring F, Daniel H, Fischer A. Localization of the peptide transporter PEPT2 in the lung: implications for pulmonary oligopeptide uptake. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:707–714. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.